North Carolinians got a painful psychic kick in 1955. Newspaper readers awoke to learn that the state’s average weekly income had slipped to last place among the then-forty-eight states—below even its laggard neighbor to the South, the Palmetto State. Yet North Carolina was the leading manufacturing state in the Southeast and the second most populous after Florida.1 Its population grew by 10 percent between 1950 and 1960, but such growth masked worrying trends: African Americans were leaving the state to pursue freedom and opportunity outside the Jim Crow South, while college graduates departed for the North, Midwest, and West to find jobs where they could use their degrees.

Meanwhile, federal investment in defense production and scientific research bolstered the economies of states such as California, Texas, and Florida, as the nation settled into the permanent mobilization of the Cold War. The rush to develop new means of defense, space technology, and nuclear power meant that the United States was willing to spend huge sums employing scientists and engineers and spawning whole new industries.2 Just next door, the federal government revolutionized a lonely corner of South Carolina, where a massive nuclear facility at the Savannah River Plant brought workers, including many scientists and engineers, to revolutionize the state’s economy.3

It was against this backdrop that a group of elite North Carolinians in business, education, and government conceived an audacious plan to change the state’s economic course. They imagined a new complex of advanced industry and scientific research flourishing among the colleges of Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill—the three points of the so-called Research Triangle—where outside companies would bring better-paying jobs than traditional sectors such as textiles and furniture, importing educated outsiders and employing the state’s own graduates. Incomes would rise, tax revenues would swell, and North Carolina would channel some of the largesse of what President Dwight D. Eisenhower would soon call the “military industrial complex” its way. It would be the next Silicon Valley, well before anyone had invented the term.

But how could North Carolina convince the world that a state with some of the lowest wages and poorest schools was a high-tech hub waiting to happen? Even one of the Triangle’s leading proponents, University of North Carolina (UNC) sociologist George Simpson, admitted that the state suffered from a “cultural problem.” Youth in the Northeast and Midwest imbibed the virtues of science and industry early on, but “our young people…grow up with little or no exposure to this sort of environment.”4 The Research Triangle, he told UNC faculty in 1957, aimed to foster the sort of creative milieu in which science flourished elsewhere. And it would do so by mobilizing the resources of its institutions richest in knowledge and culture: its universities.

While scientists and corporate managers were initially skeptical about relocating to North Carolina, Simpson and his allies were winning over companies such as IBM by stressing the importance of the Triangle’s universities to quality of life. Central to the latter’s appeal was the idea that highly educated and much-sought-after scientists and engineers would be drawn to the cultural opportunities afforded by local educational institutions—and, indeed, by virtue of living among other educated, creative people. With pamphlets and newspaper ads, they touted the state’s schools, museums, golf courses, and, above all, its “climate”—not just in the sense of weather, but in terms of “academic ambience” and “intellectual stimulation.”5 In nascent form, Triangle boosters pioneered the ideas of the creative class and the creative city, mobilizing cultural resources as a means of attracting both capital investment and privileged workers.6

Unlike earlier campaigns for southern industrialization, the Research Triangle effort did not focus simply on cheap labor—although boosters were quick to point out, when it suited them, that the state had a “vast labor pool” of flexible, affordable workers, who could be trained on the state’s dime through the new system of community colleges.7 Most often, North Carolinian leaders sold the Triangle as a special kind of place filled with people who would be valued as neighbors and workers due to their intellectual and creative qualities. They aimed to both promote and produce a certain kind of space—one where companies such as IBM and Burroughs Wellcome would be willing to relocate from New York and where highly educated scientists would be willing to live. The “atmosphere” surrounding colleges like Duke and the cultural amenities supported by an upper-middle-class population generated a value that the Triangle’s promoters in turn packaged and sold both to corporate executives and the employees they sought to hire. In the Triangle, real estate values and economic development hinged not only on infrastructure or natural resources but also on the sellable qualities of the people residing there.

By packaging the people and institutions of the Triangle area as a valuable resource, North Carolinians were able to persuade both major corporations and the federal government to bring research facilities there. But the idea of the Triangle as a “reservoir” of brains had to start somewhere—someone had to draw three arbitrary lines on a map and imagine that perceptions of social or cultural prestige could drive economic development. When Romeo Guest began circulating the phrase “research triangle” in the fall of 1954, he insisted that North Carolinians put cultural opportunities and the presence of workers with high class and educational status at the forefront of their pitch to the country at large: “We should all bear in mind that we are not selling a factory site. We are selling available engineering brains, physical research facilities and cultural living conditions.”8

THE ORIGINS OF THE TRIANGLE

Romeo Guest was anxious about the future of North Carolina. The Greensboro contractor had inherited the family business from his father, a builder of industrial sites. Its slogan was “Serving the Industrial South,” and its logo featured a city skyline encircled in a radiant glow—factories on the left, farms on the right, with the skyscrapers of the downtown business district in the center. C. M. Guest & Sons depended on the flow of new industries to the South, and Guest sensed that interest in North Carolina was flagging. “The competition for new industrial plants is becoming so keen and so competitive that it is increasingly more difficult to relocate a new plant in our State,” he wrote. He also noticed that Congress was throwing federal money at military projects and scientific research, thanks to the Cold War, and North Carolina mostly missed out on this bonanza. “I have heard that MIT has research grants from the government through industry amounting to approximately $5 million per year and that California institutions are similarly loaded,” Guest said.9

Southerners needed to look no further than Alabama for a case study of cashing in on the federal government’s sudden interest in science and technology. The city of Huntsville began to change with the building of munitions plants during World War II, and it became a center for research on rocket technology following the arrival of Werner von Braun and other German scientists, who were brought to the United States in 1945 as the Americans and Soviets attempted to divvy up the scientific minds of the collapsing Nazi regime. As Guest noted, the three thousand scientists who had come to Huntsville by the mid-1950s “changed the complexion of the community.” Whether this change of complexion was meant literally or figuratively, Guest believed that attracting scientific workers and federal dollars—as Huntsville, Boston, and other cities had done—would be North Carolina’s path to prosperity. “Our research triangle is much better suited for scientists than Huntsville,” he said. “We must point out our facilities both in personnel, physical and cultural to the Presidents and Research Directors of major corporations quickly while government research projects are still being handed out.”10

So began Guest’s mission to evangelize the idea of a “research area” in the middle of North Carolina. It required enlisting the support of bankers, governors, journalists, textile magnates, and university presidents and professors, who helped persuade corporations and government agencies to place scientific facilities in the state. This effort built on a long and illustrious history of Southern boosterism, in which city fathers and developers crowed about the immense business opportunities (real and imaginary) that existed in towns and counties throughout the Southeast. At the same time, though, it demonstrated a degree of cooperation across the privileged classes—from Governor Luther Hodges, a tenant farmer’s son who was ardently pro-business, to deep-pocketed bankers like George Watts Hill and academics like UNC sociologist George Simpson—that was remarkable even in the context of the “commercial civic elite” that had long dominated local government in the South.11

The Triangle soon developed (nearly) unflagging support of not only the local Chamber of Commerce or city council but influential people at multiple levels of government and in divergent fields of endeavor, whose interests might not have always aligned. A number of professors wondered whether their universities’ involvement in the Triangle campaign—which essentially promised prospective businesses access to their expertise and libraries—would really benefit the schools or the faculty. But their critical voices did little to stymie Guest’s ambitious campaign.

The Triangle emerged at a time when many leaders were beginning to consider the importance of knowledge, science, and technology in the South’s economic development. Boosters in High Point, a furniture center twenty miles south of Greensboro, attempted to shake off the town’s low-tech image and entreat manufacturers in the growing field of electronics to locate there in 1954. But although the technology was new, the pitch was not: the local workers were docile and homogeneous. “Of especial importance is the fact that labor in the High Point area is 99.3 percent native born,” Phil Clarke assured an executive at Olympic Radio and Television, in Long Island City, New York. “Labor relations are very satisfactory and work stoppages and labor disputes have seldom occurred and have never lasted for a great length of time.”12 Clarke did point to the existence of numerous schools, however, including High Point College and Duke University, along with their distance from the city.13

Meanwhile, leading citizens in nearby Winston-Salem emphasized cultural and intellectual resources to a greater degree. In early 1955, Fred Linton of the Winston-Salem Chamber of Commerce sketched out a few key ideas that would become important to the Research Triangle. Like any good booster, he suggested to Guest that Winston-Salem could offer a fine alternative to Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill. The twin cities, after all, hosted R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and Bowman Gray School of Medicine, and it would soon become the home of Wake Forest College, which was relocating from the east of the state. Beyond a pitch for his home city, Linton noted that the Boston Chamber of Commerce had been promoting its own resources of “scientific talent” to prospective employers for several years, and Washington, D.C., was following suit. Raleigh or Winston-Salem could do the same. “Another possibility that has been turning over in my mind for some time with no practical result is the possibility of organizing a research organization in North Carolina with private capital to do research work on a contractual basis,” Linton said. He had seen such organizations flourish in Texas and Alabama and thought the Tar Heel state could do the same.14

The germ of just such an idea originated with Howard Odum, a prominent sociologist at the University of North Carolina. Odum had seen the growth of government sponsorship for research during World War II and proposed in 1952 that the state set up a research center near the new Raleigh-Durham airport. That area would draw on the combined intellectual and material resources of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, the Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro, and North Carolina State College in Raleigh. Although leery of too much government meddling in the affairs of scholarship, Odum believed more could be done to harness North Carolina’s academic strengths for the greater good. However, Odum passed away in 1954, before his vision could be realized.15

There is little evidence that either Linton or Guest was influenced by Odum’s proposal, but North Carolinians in the early 1950s were well aware of experiments with new kinds of scientific organizations in other states and consciously looked to these as models.16 Guest had studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology as a young man; witnessing the concentration of scholarly activity in Cambridge inspired him to see in Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill the potential for a Charles River of the South.17 He and his colleagues visited Birmingham, Alabama, in early 1955 to study the Southern Research Institute (SRI), a center for chemistry and biomedical research launched in 1941. Among the nation’s first such centers, SRI would soon serve as a model for the early planners of Research Triangle Park.18 Guest carried on a correspondence with the institute’s leadership in the following months marked by mutual respect as well as competition. “Since returning from Birmingham after visiting your fine research institute, we have been trying to formalize our thinking in connection with our own Research Triangle in North Carolina,” Romeo Guest wrote. He admitted, “The progress of the Triangle has been most interesting so far and really catches my interest to the point of my finding it difficult to turn my thinking into other channels.”19 William T. Polk of the Greensboro Daily News shared this enthusiasm when Guest shared the idea for the Research Triangle with the writer and editor in December 1954: “I think you have got hold of something very important and practicable here. North Carolina and the South need research, perhaps more than anything else.”20

Thus, when Guest began to drum up support in late 1954, numerous North Carolinians had already been thinking about ways to bring higher-skilled and higher-paid jobs to the state. What later became known as the Triad—a junior competitor to the Triangle encompassing Greensboro, High Point, and Winston-Salem—could have taken the lead. Each town had its own colleges to boast about. Interestingly, Guest chose not to focus on the Greensboro area, despite its being his home base. By winning the support of Governor Hodges and key leaders at Chapel Hill, Duke, and North Carolina State College, Guest was able to fix the attention of private businesspeople, state development officials, and even faculty members on recruiting business for the Triangle. Guest contacted Hodges’s office in December 1954, and by the following November, the Research Triangle Committee met to discuss what exactly the Triangle would be.21

In fall 1954, Luther Hartwell Hodges was new to the lieutenant governorship. The businessman had had a varied career before he pursued that office in 1952, working his way up to manage Marshall Field’s textile mills in the Southeast and working on the Marshall Plan in Europe following World War II. At 52 he retired to devote his remaining years to public service and had won a spot on William Umstead’s ticket for governor after a campaign that took him to gas stations across the state. Umstead, a Democrat, won handily in a state where, to this day, few Republicans have held the governor’s mansion, but he was in poor health. So poor, in fact, that the political novice Hodges was thrust into the limelight when the governor passed away in November 1954. Soon after, he received a call from Romeo Guest.22

The new governor took up Guest’s cause almost immediately, perhaps looking for some stamp to put on the economic development efforts of his administration. Hodges was anxious to attract outside investment, traveling everywhere from Chicago to the Soviet Union to sell the virtues of North Carolina. The governor later recalled in his 1962 memoir that the Triangle was “an idea that has produced a reality”—but in its early phases the idea itself was far from clear.23 In March 1955 Hodges told the Raleigh News & Observer that the Triangle could compete with the international stature of MIT, which was “ringed” by labs. “Many industries…have located centers in the vicinity of the school in order to take advantage of M.I.T. staff and facilities,” the paper reported. “The same thing could happen in North Carolina,” according to Hodges. “It would bring in more Ph.D’s than we’ve ever heard of here.”24

To hear Hodges speak, one would think he intended only to import more people with advanced degrees. After all, the South’s school systems were notoriously impoverished, and the region was short on highly educated workers. As historian James C. Cobb noted, “Research scientists were more than five times more numerous in the nation as a whole than in the South, and patents were issued to southerners at a rate less than one-third of the national average” by the end of World War II.25 Indeed, Triangle planners would continue to speak frankly about their aim to “import” scientists who would, presumably, elevate the tax base and workforce in the state.26

But what, in fact, was the goal for the Triangle’s early supporters? Was it simply to shift the state’s recruitment efforts from attracting factories to wooing laboratories? Was it to set up a research center or institute along the lines that Howard Odum and Fred Linton had proposed? Was it to be a real estate venture? (Stanford Industrial Park, the nation’s preeminent research park, had been designed to generate revenue for its parent university in California.27) Was the campaign meant to stimulate the birth of new industries at home, or was it to attract outside corporations to the area?

For the plan’s boosters in politics and the press, these goals were not mutually exclusive. “The three institutions are rich in scientific knowledge and technological skill,” a Durham paper noted in January 1955. “The plan is to utilize these facilities in attracting industrial laboratories to the area. From out of these labs new industries are expected to be born.”28

“Hatching” new industries or luring new ones with better wages and higher demands for skill presented a fresh set of challenges.29 Southern leaders had been bending over backwards for years to seduce Northern companies with tax incentives and offers to train workers and build facilities. Yet North Carolina’s approach to attracting investment remained limited, for the most part, to promises of infrastructure, such as better roads, and the implicit guarantee of a docile, nonunion labor force, rather than offers of tax breaks. Guest sent his vice president, Russell A. McCoy, to sound out the local commissioners in Durham, Orange, and Wake Counties on the idea at the start of 1955.30 McCoy proposed that the counties eliminate ad valorem taxes on research-intensive companies for ten years, perhaps longer.31 Such incentives did not benefit any outside enterprise that might create jobs but, rather, signaled that local authorities prized particular types of jobs and investment.

Guest and his allies also attempted to finesse the national and local media into grabbing attention for their project. “You know I am interested in what you people are doing in the state of North Carolina,” Frank P. Bennett of America’s Textile Reporter assured Guest, “so you remember that if there is any way we can give the whole thing a boost that we want to do it.”32 (C. M. Guest & Sons had advertised its services in the textile industry journal before.) Guest reached out to his friend Peyton Beery in Charleston, South Carolina, to curry favor with Business Week, where Beery knew the managing editor, Kenneth Kramer. In June, William A. Newell contacted Kramer to spell out the group’s message. “The news peg for Business Week…is two-fold: a challenge to the Charles River as the nation’s research center, and a further step in the growth and development of the industrial South,” said Newell, director of the Textiles School at NC State. “Add to that the rather unprecedented coordination of University research efforts and the factors that favor and stimulate this development, and you should have a story.”33

Meanwhile, Guest sought to win the backing of academic leaders, whose cooperation was crucial given that the presence of colleges, faculty, and libraries was central to the Triangle public relations blitz. Guest told state Senator Arthur Kirkman that he had gotten the go-ahead from Duke in January, while Walter Harper and Dean Lampe of North Carolina State College had shown their interest and support the year before.34 However, not all members of the academic community were pleased with the idea of hitching the colleges to Romeo Guest’s wagon. When leaders from the three universities met in February 1955, a few voiced uneasiness with the concept of the Triangle, objecting to “wording which looked like Guest was offering their services and had the whole program in his hip pocket and could just go off and sell the program without letting the institutions have much part in saying just what they could offer”—in short, that the contractor would “get the institutions in over their heads.”35

Notably, N. J. Demerath, a professor of sociology at UNC, expressed his misgivings to Guest two months later. “Your idea of an ‘M.I.T. of North Carolina’ as reported recently in the press is most intriguing,” Demerath wrote. “It brings to mind, however, certain factors affecting research achievements at the University of North Carolina which may run counter to the realization of your idea as well as President Gray’s goal of ‘Excellence’ for the University. Permit me to note briefly these tendencies to educational and research mediocrity.” The professor went on to note that most faculty had little extra funding to support their research, and budgetary pressures led administrators and state officials to push professors to teach more than their “low” course load. Demerath also warned that the “humanist-documentary tradition” at Chapel Hill disdained consulting and applied research.

In short, the professor worried that the Triangle project would sap already scarce resources from the educational institutions while entangling faculty in relationships with outside interests that did not serve the mission of scholarship. After all, what did it mean for the faculty and resources of the colleges to be “available” to new industries that came to the area? “The ‘Triangle Research Plan,’ therefore, like the proposed North Carolina Board of Higher Education,” he concluded, “may be perceived as one more administrative imposition to be tolerated or opposed unless effective communication is generated with local faculty members.”36

Indeed, others at the universities shared Demerath’s misgivings. One university official chided Guest, “Let me see, Romeo, if I really understand what it is we are talking about here, you want the professors here and all of us to be the prostitutes and you’re going to be the pimp.”37 George Simpson, the UNC sociologist who was soon picked to head up the Research Triangle’s “pimping” mission, addressed the issue with more characteristic circumspection. “There is always a chance that the university will be taken, inadvertently, into waters in which it has no business swimming,” he observed in 1957. “It is possible some substantial freedom of action may be lost, or that some action may be forced upon the university by the pressure of circumstances.” But he assured fellow faculty members that UNC President William Friday and the other university leaders were committed to resisting “anything that was detrimental to the character and the basic educational and research programs of their institutions.”38

Despite doubts among some faculty, the Research Triangle Committee spent the next several years attempting to persuade outside corporations that the universities were a major draw for placing facilities in the general area around Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill. In a July 1955 meeting, Hodges was asked why such industries had not chosen to come to North Carolina, and he guessed that a combination of “the living conditions of North Carolina people, tax rates, water sites, and the lack of available technical corps” was to blame. The group decided to compile an inventory of local resources, such as the schools’ many laboratories, NC State’s atomic reactor, and the area’s “comparatively large number of hospitals…that would be attractive from the standpoints of health facilities for workers and markets for pharmaceuticals and medical equipment concerns.” The inventory also would take note of “cultural opportunities” offered by the Triangle cities.39

The group soon appointed Simpson as its director—essentially, an itinerant pitchman for the Triangle, who would travel across the country to speak with scientists, executives, and policy makers.40 In 1956 the professor met with the “appropriate research people” at “the Air Force, the Navy, the Army, the National Science Foundation, [and] the Atomic Energy Commission”—key among the many fonts of federal money at the height of the Cold War.41 Meanwhile, chemist William F. Little of UNC met with representatives from Buckeye Cellulose, Chemstrand, Ortho Pharma, and Scott Paper at Chapel Hill in early 1957.42 “All of these people showed real enthusiasm for the idea and without exception, have promised to turn over the brochure I gave them to research directors, etc.,” Little reported to Simpson.43 In fact, the men from Dow in Texas showed special interest. “It was an absolutely glowing letter of praise for our area,” Little said. “Coming from Texans this is something.”44

Still, Guest and his allies had been receiving kind words about their project for several years without realizing tangible results. Simpson began to sense that the committee needed a flagship project to build interest. As he reflected in February 1957,

There is great value in having something concrete, something that can be mapped and walked over, to place before people. Something tangible stimulates the imagination. The necessity of doing this has been growing on me all along. I became finally convinced last week in Indianapolis, in talking to Dr. Carney, the Vice President of Eli Lilly for Research, Development and Control. He took an unusually sympathetic interest in the project, and he stated quite baldly that this would be of great value, especially in putting across the idea to non-scientific people.45

Simpson felt that such a project could be public or nonprofit, like the Research Triangle Committee itself, but he admitted that a for-profit venture might be more likely to succeed.46 He envisioned raising funds to purchase a chunk of land in the middle of the Triangle, a “research campus” where companies could locate their laboratories in close proximity to one another. The Research Triangle would not be just the general area of Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill but a Research Triangle Park where high-tech companies operated side by side.

In March 1957 Governor Hodges reached out to retired textile magnate Karl Robbins about funding land acquisition.47 Robbins was born in Russia around 1893 and emigrated to the United States as a young child. He took over his father’s store in New York and began to invest in the southern textile industry, soon becoming a major figure in North Carolina manufacturing. Robbins had sold his textile stock in 1954 and turned his interests to philanthropy, working to found the Albert Einstein College of Medicine at Yeshiva University and the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies in New York. In North Carolina he had been known for setting up playgrounds and parks in the communities where his workers lived, and the town of Hemp was renamed Robbins in his honor.48 (This was the town where disgraced presidential candidate and former Senator John Edwards spent his oft-mentioned working-class youth.)

Robbins’s interest in the Research Triangle reflected this sense of noblesse oblige. “I always wanted to find some way to help those in our industrial family who were so generous with their skills and loyalty,” he said in a letter to Governor Hodges. “Through Christmas bonuses, creation of recreation facilities and steady jobs at better than standard wages, we tried to do our bit in raising the standard of living in the areas of our mills. But an effort at that level can only help the few thousand who are on the immediate payroll. So I am tremendously interested in the Research Triangle because through research you look ahead and create out of man’s mind wonderful things for his future.”49 Robbins also had been inspired by an article on a “science city” then being built along the Ob River in Siberia.50 “You see, we are having competition,” Robbins told Hodges in June 1957, “but I assure you, in no way will their’s [sic] be as nice as the one we plan to have in North Carolina.”51

Doing his “bit” for North Carolina meant ponying up $1 million to purchase land around the villages of Nelson and Morrisville in southeastern Durham and northwestern Wake Counties (figure 1.1).52 The operation would turn a profit, Robbins hoped, as the land was sold or leased to companies that set up labs there. Buying thousands of acres, though, even in a relatively rural area, was bound to draw attention, and the local press helped suppress the truth. “This is a highly explosive powder keg we are sitting on and anything can happen,” Guest warned Saunders in June. “Many rumors began flying in the Nelson-Morrisville-Airport area once persons caught on to the wholesale acquisition,” a local paper reported, after news of the purchases broke. “Some speculated the land was to be used for an atomic power plant or at least an atomic reactor project of some kind. Others figured the federal government wanted it for some other kind of hush-hush project.”53

Figure 1.1 Durham banker George Watts Hill explains the Triangle map to Romeo Guest, George Simpson, and two others (right to left) in 1958. Source: Research Triangle Foundation.

Hodges called in top figures from the press and urged them not to write about the project until the acquisitions were complete. Guest warned Robbins in July that “the newspapers are onto our forestry man’s acquisition and have guessed what it is for. The most influential man in Durham [presumably George Watts Hill] is trying his best to stop the newspapers from publishing anything. We don’t know if he will succeed.”54

Robbins’s men succeeded in buying up most of the desired land, thanks in no small part to the press blackout. Guest was well aware of incidents when such efforts went awry, as when development officials in Warrenton, North Carolina, ended up paying $2,000 per acre for land that was purportedly worth $200 because the “secret” got out—the secret being that the land might be worth much more if the sellers knew a major industrial development was to be built there. “There are only a few gaps in the research park site,” journalist O. Mac White reported in 1957. “These pockets are homesites which occupants didn’t want to give up.”55

With land purchased, the Triangle Committee was finally making material progress. The sales trips of Simpson and other faculty members seemed to be paying off. The committee’s promotional brochure made the rounds at the chemical company Monsanto, and a vice president conveyed his interest in the Triangle in January.56 The committee began drawing up plans for a research institute in April.57 In a meeting at Pfizer, Dr. Robert J. Feeney told Simpson that the pharmaceutical giant was tired of its headquarters in “an undesirable area” of Brooklyn, and that they would consider moving to the Triangle.58 Simpson also believed they had viable leads in the United States Testing Company, and Robbins was personally leaning on his friends at the Hoboken-based firm’s board of directors.59 By September the Research Triangle received favorable coverage in the New York Times, and Karl Robbins was “buoyant,” according to Guest. “Thank you for a job exceedingly well managed,” he told the governor.60

THE TROUBLE WITH THE TRIANGLE

The Triangle had land; it had the active support of a network of high-placed individuals in academia, finance, industry, media, and state government; and it appeared to have leads for potential tenants. However, certain flaws in Romeo Guest’s design became evident as the plan moved forward. Some involved the logistics of local politics, infrastructure, and taxation, while others related to the viability of the Triangle as a for-profit real estate venture.

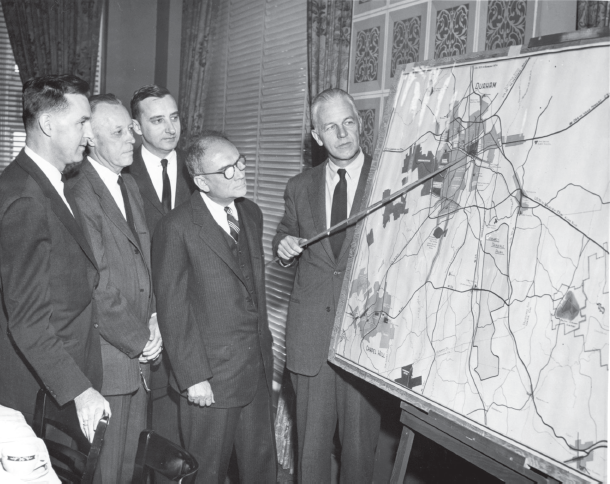

First, it was by no means clear how the research park would fit into the jigsaw puzzle of state and local government. Robbins spoke of a “science city”—would it be a town unto itself? It would soon have its own zip code; one could mail a letter to Research Triangle Park, North Carolina (figure 1.2). Could it turn to neighboring municipalities for water or the state for roads? Whether as a public project or for-profit enterprise, the park would have to obtain the basic resources, and laws as they existed in 1957 did not necessarily allow for a new development that straddled two counties to do so.

Figure 1.2 Sketch of a Research Triangle Park sign, ca. 1963. Source: Research Triangle Foundation.

For instance, Simpson noted that state law permitted several counties to create a joint water and sewer authority, which they could provide with money for “preliminary” costs—presumably for surveying. This authority could then issue bonds to raise money for building water lines. However, planners were uncertain that a city could provide water to a site far from its city limits and extending into another county, even if local officials supported it. The state legislature considered a law in May 1957 that would allow cities to provide water to areas ten miles beyond their borders, but Simpson was dubious. “Certainly any such legislation would be subject to lawsuits,” he told the governor, “and probably would be of little value until the matter had been settled in the courts.”61

Local attitudes toward the project varied throughout the Triangle. Durham’s relationship with the research park was particularly vexed, from initial discussions of whether to provide it with water at reduced city rates to subsequent attempts to annex the park (and thus raise revenue) in the 1970s and 1980s.62 Some in Chapel Hill were less thrilled. “It is not exactly clear what Gov. Hodges means by the ‘scientific city’ which he enthusiastically proclaims is to rise within 20 minutes’ ride of Chapel Hill,” the local News Leader commented in an editorial in 1957. The editors wished the project well but still wondered what effect a new settlement of as many as 25,000 people would have on the nearby college town. Chapel Hill “wishes to preserve its own character as a nonindustrial community centering around a major institution of learning,” the article said, but the Research Triangle threatened to reorient the university’s priorities, setting science and industry above its traditional emphasis on the humanities. “The growth of a city devoted wholly to scientific research so nearby will of course exert a major influence on the life of this whole area,” the News Leader item concluded. “But this community will hope that meantime Chapel Hill’s present aims and purposes will not be lost to sight, and that its ancient heritage as a seat of learning will not be overlooked.”63

Such skepticism extended beyond the pages of the town newspaper, as the research park struggled to generate the kind of interest—and land sales—that seemed so plausible in the spring and summer of 1957. A business downturn that year left many companies reluctant to take a chance on the Triangle’s as-yet-unproven potential as an ideal location for industrial laboratories. Three clients who had planned to move to the park failed to follow through.64 A luncheon for potential investors in Charlotte in July 1958 yielded little interest, and Guest regretted having not planted any questions in the audience. Meanwhile, Pinelands was running short of funds. “I have now decided to plow into this thing full speed ahead without regard to anything except the final answer,” Guest wrote in frustration to his friend Claude Q. Freeman, a Charlotte lawyer who helped recruit the city’s business elite for the luncheon. “To me, the final answer is that Pinelands needs $2 million and it is up to me to get it.”65

Robbins, in poor health by the fall of 1958, appeared to be unhappy with the direction of the project. As few companies showed interest in relocating to the area and the project’s profitability was in doubt, the Research Triangle Committee realized that the project was likelier to succeed as a nonprofit venture. With the energetic support of banker Archie Davis, the committee was able to raise enough donations from wealthy North Carolinians by 1959 to buy out Robbins’s shares and reorganize itself as the Research Triangle Foundation, a nonprofit that would be jointly controlled by the three universities and the state. Thus did the fledgling Research Triangle Park change from a private, commercial effort to a joint public-private partnership—albeit one without many interested tenants lined up.66

Clearly, businesses were not champing at the bit to relocate to the Triangle in 1958. Boosters could claim that Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill was an ideal area for scientific research, but skeptics would remain skeptical until corporations actually began to set up shop there. A. H. Kinzel, a chemist at Union Carbide, was not sanguine about the Triangle’s prospects. Meeting with Simpson, Kinzel said that the existence of nearby research facilities was simply not a major factor when his company was deciding where to put a laboratory. Carbide would not consider the chemistry labs at Duke or UNC to be a compelling reason for locating a facility in the area, as academic research was often too slow-moving and remote from practical application to make much of a difference for the company.

Usually, he said, the laboratory will follow the plant, and in the case of his company the plants have in recent years been located generally with reference to water supply. He pointed out the deficiencies of our area and of the South in general in the services that are necessary to support research activities, such as engineering, skilled workers for machine making and the like, the proximity of supplies, and a large skilled laboring force from which to choose. This was not the first time that this point had been made to me.67

Kinzel did not mince words. The chemist, Simpson recalled, “took occasion, also, to point out that in the national setting our three institutions, while quite good, did not loom especially large to such a person as he.”68 The sociologist was not offended but, in fact, took the candid words for what they were: a frank assessment of the challenges involved in persuading outsiders that a patch of piney woods between two modest-sized cities and a small college town in the South was a hotbed of scientific innovation. How could you build an “M.I.T. of North Carolina” without an MIT or Boston to go with it? If the Triangle’s seeming raison d’être—its concentration of scholars and scientific resources—had only marginal utility for big business, what could be its chief selling point?

Boosters argued that geography favored the Triangle in other ways—as embodied in the rail lines, highways, rivers, and airports that criss-crossed the pages of the promotional literature. The Triangle was situated between New York, Atlanta, and Washington, D.C., at a nexus of transportation routes, including the new interstate highway system, then in its early stages of construction.69 “The town [Chapel Hill] is twenty minutes from a regular air terminal connecting with Washington in an hour and Atlanta in one and one-half hours,” Guest told the director of engineering at E. R. Squibb & Sons, a pharmaceutical firm that was itself headquartered in a college town, New Brunswick, New Jersey. Crucially, scientists and executives could catch “overnight service to New York on fast trains.”70 The research park offered direct access to the Southern and Seaboard System Railroads, and North Carolina Highway 54 converged with U.S. Highways 1, 15, and 70 in the area.71 “The industrial scientist thus may live in an environment peculiarly suited to him and yet remain in close touch with executive offices and perhaps even production facilities located elsewhere,” explained Simpson in a 1957 promotional piece in the New York Times.72

When IBM announced plans to build a research center in New York’s Westchester suburbs in 1956, the company appealed to the same mix of geographical and social qualities that would define the Triangle’s message. IBM officials cited Westchester’s proximity to its other facilities as a top concern, just as Kinzel suggested. “The Westchester County site on which we hope to build is located midway between Poughkeepsie and New York City,” president Thomas Watson said. However, a convenient location between its labs along the Hudson River was not the only consideration. “It was selected not only with an eye to accessibility but to the considerable cultural and educational opportunities in the area,” Watson told the New York World-Telegram and Sun. “These are of great importance to scientists, whose interests individually and as a group are extremely varied.”73

Guest anticipated this line of argument three years earlier, when he first tried to convince Squibb & Sons to come to the “research area” of Chapel Hill. “In my other work with pharmaceutical firms,” Romeo Guest told Squibb’s director of engineering, “I have found that the matter of location near the center of culture is very important.” North Carolina’s cities each had something to offer in terms of culture, but one area stood out: “It is a place where you can get plenty of workers easily and at the same time, it is a place where research chemists with doctor’s degrees would be very happy because of the association with culture and extra training.”74 This approach was an attempt to sidestep strictly practical arguments about the importance of universities, libraries, and labs to an industrial firm. Instead, it focused on the appeal of the area to a company’s workforce, both in practical terms—the availability of further training and graduate education—and in more diffuse terms, in the atmosphere of culture or sophistication in which “research people” would want to live.

G. H. Law of Union Carbide offered a contrary view from his colleague Kinzel, arguing that these less tangible factors, such as culture, could be important when businesses choose a site for a laboratory. Law told Simpson that “living conditions and cultural opportunities” were “at least as important as any other considerations” for corporations and the scientists they hoped to employ. At a time when the federal government and private industry were putting unprecedented resources into research, highly educated professionals were in short supply and high demand. “There just aren’t enough good men to go around and competition is intense,” Law said. “With equal opportunities and salaries at different locations the decision to accept a position is usually made on the basis of living conditions. Many of the young men we hire now are married before they leave school and their wives frequently cast the deciding vote on location.”75

Crucial to the success of the Triangle, then, was an emphasis on the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill area as a place where scientists could be happy and creative. In this sense, both the Triangle’s champions and the corporations that moved there needed to present the urban landscape as valuable, rich in culture and social status. The production and sale of this new kind of space predated the discourse of “innovative milieux” and “creative” cities that came into vogue in the 1990s and 2000s.76 North Carolinians spoke of the value of the Triangle’s educational institutions and privileged workforce in terms of “climate,” “atmosphere,” and the ubiquitous language of “stimulation.” Such rhetoric resembles the more recent trend toward emphasizing “diversity” and other qualities of neighborhoods and cities that accompanied gentrification amid the renaissance of cities such as New York and Boston in the 1990s, even though the Triangle was—at least at first—cultivated as a landscape for affluent white residents.77

Research Triangle Park emerged at a time of intense competition for scientists and engineers, particularly after the Russian satellite Sputnik’s flight in 1957 exploded American fears of a technological lag in the race for Cold War supremacy. Companies were painfully aware that workers in new high-tech industries had to be cajoled to take a job, even with a company as powerful as IBM, and the qualities of a working and living environment soon became central to their recruiting efforts. As the federal government subsidized work on space technology and computing during the 1950s and 1960s, employers vied to recruit a scarce number of scientists and engineers with advanced degrees. “With the intense competition existing today for scientific talent, industry is finding that it must offer more than just good pay to attract the kind of people it seeks,” an ad in the New York Times declared in 1962. If research was a new kind of industry, its workers also had new interests and demands: “When evaluating locations for new research operations, industrial concerns also look for proximity to entertainment and cultural centers.”78

The task of the Triangle’s boosters was to convince companies such as IBM that North Carolina would satisfy the desire of potential employees for good schools, entertainment, recreation, and so forth. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Carl Madden said the Research Triangle was one of the places that attract “these brilliant, creative people,” like “Route 128 in Massachusetts, with the facilities of Harvard and MIT,” and Stanford in California. “The Research Triangle is also an outstanding area in which the industrial scientist’s family may live,” an ad by North Carolina’s Board of Conservation and Development (BCD) announced in 1957. “To be found here are most of the advantages of a large metropolitan area, without many of the disadvantages of congestion and noise and lack of space.”79

Beyond the standard pitch of suburban pleasures versus urban blight, the ad reassured readers in the Northeast that central North Carolina offered abundant cultural opportunities: “Each year many concert artists and groups appear here, along with many touring companies of Broadway shows, and scarcely a week passes during the fall and winter months when a speaker of national reputation does not appear somewhere in the Triangle.” Such luminaries included speakers such as Ralph Bunche and Robert Frost and performers including the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and the Quartetto Italiano—entertainments that catered to highbrow tastes.80 One could leave New York, in other words, without leaving Lincoln Center.

Boosters attributed these cultural amenities to the presence of scholars, students, and schools in the greater Triangle. “In Durham the flavor of fine universities blends with the tempo of diversified manufacturing set by American Tobacco Company, B. C. Remedy, Durham Hosiery, Erwin Mills, Liggett and Myers, Wright Machinery Division of Sperry Rand, and other leaders,” another ad stated in 1957. “The result is a stimulating atmosphere where a productive day’s work—whether it be in the factory, laboratory, office, or class room—is the accepted standard.”81 The Research Triangle Institute, a think tank that carried out projects with business and government on a contract basis, sought to woo potential employees in 1962, stating, “A stimulating environment for professional and cultural development is provided by close association with the Triangle universities: Duke, North Carolina, and North Carolina State.”82

The Triangle’s supporters at first experienced only modest success in convincing major corporations that North Carolina would satisfy the desires of potential employees for good schools, entertainment, and recreation. Simpson, Little, and company courted the likes of American Cyanamid and Union Carbide, which sent three representatives to tour the area in July 1958.83 The physics consulting firm ASTRA relocated from Milford, Connecticut, to Raleigh in 1958, with plans to move into RTP.84 The first major tenant, though, was Chemstrand, a chemical firm that opted to move its facilities from Decatur, Alabama, in 1959. Ironically, in their quest to imitate the Charles River and draw business from the North, the Triangle’s organizers poached a business that was thirty minutes away from Huntsville, one of the South’s other scientific centers. Chemstrand hired the Wigton-Abbott Company of Plainfield, New Jersey, to build its $7.5 million site in 1959, which was dedicated three years later.85

When businesses decided to open facilities in or near RTP, they adopted nearly identical rhetoric (figure 1.3). Chemstrand stressed that “a principal factor in [its] decision was the stimulating research climate already established in the Triangle, with its proximity to 900 scientists at State College, Duke University, and the University of North Carolina, and to the research staff of the new Research Triangle Institute.”86 The company promised prospective mechanical engineers that the Triangle “offers excellent facilities for cultural and recreational activity.” The Triangle “was chosen after a six-month study of 21 locations because: You and your family will enjoy living in this area where educational, cultural, recreational and residential facilities are top-notch. You will find intellectual stimulation in the university atmosphere which will surround Chemstrand’s expanding research program.”87 Similarly, the Missile Battery Division of the Electric Storage Battery Company tried to lure engineers to the Triangle’s “unusual intellectual climate” in 1960.88

Figure 1.3 A prototypical image of the white male researcher from a 1957 state promotional piece.

What is this “flavor,” “climate,” or “atmosphere” that so “stimulated” a certain kind of worker in the 1950s and 1960s? Like many economic development efforts, which speak in terms of numbers of jobs created or feet of floor space planned by business, the Triangle’s virtues could be quantified. In an early instance of national media attention, the New York Times observed that North Carolinians hoped to maximize the advantages of “three major universities with 2,000 faculty members, 18,000 students, libraries and laboratories.”89 The three universities were said to host “33,000 students and faculty members” in 1966.90 That same year, a state ad boasted that the Triangle included “three of the nation’s leading universities and more than 450 scientists.”91 “It’s a creative community,” another ad declared. “With plenty of educated men and women.”92

Educated people were a sort of resource to be mined or consumed. Surgeon General Luther Terry described the Triangle as “reservoir of experienced consultants in nearby distinguished academic institutions” in 1965.93 An envious Florida columnist noted the same year that North Carolina “has taken this reservoir of academic talent, created a $2 million foundation to promote and develop it, and established a Research Triangle park to attract industrial research institutions. Thus it is far ahead of states like Florida in readiness to capitalize on the most attractive adjunct to the 20th Century’s technology revolution—research.”94

The key, though, was that this “reservoir” was thought to appeal not only to management but to employees themselves. “Scientists like to live where other scientists live and where they will have the facilities they will need to carry on their work,” an item in an Oregon newspaper noted, in contemplating that state’s own potential as a research center.95 A 1962 study of Boeing employees found that 80 percent of its scientific staff considered the existence of the University of Washington in Seattle a major contributor to their job satisfaction.96 A columnist in Miami believed that the moral of the story was simple. “There is no ‘which-came-first-the-chicken-or-the-egg?’ argument in this story,” Atlanta journalist and editor Ralph McGill opined in 1964. “The educational institutions were there. Industry and science came to them. The difference between a community making itself educationally eligible to attract modern industry and one that struggles to get a pants factory primarily is one of education.”97

The argument for the Triangle, then, hinged on the universities and the people they employed and taught. Business leaders in New York’s Hudson Valley commissioned a report by consultants at Arthur D. Little in 1967, which noted that the upstate region lacked the kind of educational programs that would attract both business and workers. “An increasing number [of women] are taking advantage of extension programs,” the report said. Women who had foregone careers or advanced education to raise families increasingly looked to take advantage of nearby universities, which were more accessible in the Research Triangle than in the Hudson Valley, where few schools offered master’s degree programs. “The availability of facilities to meet the educational desires of wives is often an important consideration in the choice of jobs by scientists,” the Little researchers concluded.98

It would be too much to say that the Research Triangle succeeded entirely due to its self-promotion as an enclave for the privileged and well educated—a sort of stimulating, yet homogeneous, community. However, the idea that scientific workers would like to cluster together was as important as the notion that laboratories and industrial facilities would benefit from agglomeration economies by gathering in one area. The Triangle was both a concentration of technological and scientific infrastructure and a concentration of social capital, which was possessed by skilled workers whose training was in demand. As the geographer Blake Gumprecht observed in a rare study of college towns, these settlements are unique in “their youthful and comparatively diverse populations, their highly educated workforces, their relative absence of heavy industry, and the presence in them of cultural opportunities more typical of large cities.”99 North Carolinians helped to pioneer the sale of such traits for the purpose of regional economic development, seeking to draw both private and public investment to the “academic archipelago” that existed throughout the twenty-five-mile radius around RTP. They also, unwittingly perhaps, helped to develop a blueprint of what an information-oriented, high-tech landscape would look like: quiet, clean, with no smokestacks in sight—what geographers David Havlick and Scott Kirsch have called a “production utopia.”100

North Carolinians in the 1950s realized that their state was facing serious economic headwinds, and in response, a handful of wealthy and well-connected citizens joined forces to chart a new course for the state’s economy, one that focused on higher wages and scientific research. Romeo Guest saw that the universities of Raleigh, Durham, and Chapel Hill could serve as the springboard for some kind of high-tech development, though at first the end result was by no means clear. Leaders in academia and business pointed to the Triangle’s value as a cultural center, a community of educated people that any scientist would be happy to have as neighbors.

With the menacing orb of Sputnik floating overhead and the Cold War at full tilt, the nation’s scientists and engineers could be choosy about where to live, and the Triangle’s boosters presented the region as ideal for footloose corporations. It was, as Simpson put it, an “environment…in which there are professional colleagues and a rather high cultural level,” but without “the disadvantages of metropolitan congestion.”101 Boosters presented the Triangle as the ideal place for high-tech firms as well as scientists and their families to relocate, capitalizing on the prestige and cultural opportunities offered by the area’s universities to launch a novel development strategy based on creativity, culture, and education.

Such was the picture that the Triangle’s inventors sold to the world. But what did this utopia look like on the ground, once glass and steel began to rise from the red clay of Durham County? How did Research Triangle Park model a vision of a new economy as new jobs and new businesses came to North Carolina in the late 1950s and 1960s and a postindustrial capitalism was beginning to take shape across American society?