CHAPTER 4

Is Franklin D. Roosevelt Physically Fit to Be President?

Franklin Roosevelt’s assault on the White House began in earnest two full years before he successfully captured the presidency—on the very day after his reelection as governor, in fact, when James A. Farley, his campaign manager and state Democratic chairman, told a hastily arranged press conference: “I do not see how Mr. Roosevelt can escape becoming the next presidential nominee of his party, even if no one should raise a finger to bring it about.”

1 In point of fact, more than a few fingers

were raised against it, and though he was the heavy favorite from the outset, FDR’s claim on the nomination was far from the sure thing that the confident Farley had predicted.

During 1931, Farley toured the country, gauging support for Roosevelt, while the still-undeclared candidate himself wooed Southern Democratic leaders at Warm Springs. He had a formidable hurdle to overcome: Back then, the nominee had to win two-thirds of the national convention votes, rather than a simple majority, which meant that any major bloc of delegates effectively enjoyed veto power.

Prohibition, in force since 1920, remained a significant issue, particularly in the Midwest and the Bible Belt. And while its importance had waned, given the national economic crisis, the issue had proved insurmountable for Al Smith four years earlier. Foreign policy also was a sore point in some quarters, notably to publishing tycoon William Randolph Hearst, still an influential figure and a devout isolationist. On New Year’s Day 1932, in fact, Hearst endorsed John Nance Garner of Texas, the Speaker of the House, for the Democratic nomination, calling on the party to reject Wilsonian internationalists.

2Meanwhile, Roosevelt assembled the team that would be known as his vaunted “Brains Trust”—people like Raymond Moley, Rexford Tugwell, Harry Hopkins, and Adolf A. Berle. Yet even with that intellectual star power, Roosevelt was viewed in some circles as a vacillating lightweight, particularly as he avoided going too far out on a limb on contentious issues. Chief among his critics was the nation’s leading newspaper columnist, Walter Lippmann, of the

New York Herald Tribune. FDR, wrote Lippmann, lacked “a firm grasp of public affairs. . . . He is a pleasant man who, without any important qualifications for the office, would very much like to be President.”

3Going into the Democratic convention, Roosevelt—following a string of primary victories—was the favorite, but not prohibitively so. His onetime ally, Al Smith, mobilized a “Stop Roosevelt” campaign that nearly succeeded: FDR led on the first day of balloting with a clear majority, but it appeared that he would be unable to win the two-thirds needed for nomination. Finally, Roosevelt cut two deals: He offered Garner the vice presidency, ensuring the support of Texas’s delegates, and gave former Treasury secretary William G. McAdoo, Woodrow Wilson’s son-in-law, who controlled the California delegation, veto power over his cabinet choices at State and Treasury.

Those two switches put Roosevelt over the top on the fourth ballot. In a move that electrified both the delegates and those listening on the radio, Roosevelt broke with tradition and flew to Chicago to personally accept the nomination in a speech that closed with the historic vow: “I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a New Deal for the American people.” To the strains of “Happy Days Are Here Again,” a song from the otherwise obscure 1930 film

Chasing Rainbows, the convention hailed its new standard-bearer.

4But while FDR had already disposed of the health issue as far as New York voters were concerned, doubts remained elsewhere about his physical fitness for office. And the Republicans were quick to capitalize on those fears. So were elements within his own party: As early as April 1931, Mrs. Jesse W. Nicholson of the National Women’s Democratic Law Enforcement League, which opposed the repeal of Prohibition, told her assembled members in widely quoted remarks that Roosevelt, “while mentally qualified for the presidency, is utterly unfit physically.”

5 Such sentiments, though rarely voiced publicly, continued into the fall campaign—so FDR, Farley, and Howe decided to tackle them head-on.

Roosevelt himself never addressed his health in the kind of comprehensive speech that a presidential candidate today might be expected to make. Indeed, after being told of widespread rumors that he’d been brought to Warm Springs on a stretcher to be treated for an undefined “very serious illness,” Roosevelt declined to engage in any “propaganda stunt” to prove he was healthy.

6 But neither did he avoid the issue. During a September campaign swing through Portland, Oregon, FDR made a point of visiting a hospital for crippled children, where he told the patients, “It’s a little difficult for me to stand on my feet, too.”

7 Mostly, however, the issue was handled by surrogates, both medical and political. U.S. Senator Royal S. Copeland of New York, a former professor of homeopathic medicine, pronounced Roosevelt perfectly fit, saying he had “shak[en] off every temporary vestige of his serious illness.” Indeed, he added, Roosevelt’s “lameness . . . has proved to be no more than a trifling physical handicap to a very active person.”

8 Another Roosevelt medical friend gave an even more misleading reassurance: Dr. Francis E. Fronczak, city health commissioner of Buffalo, New York, insisted the candidate had been “the victim of an illness, not so rare, which resulted in temporary, partial disability of the leg muscles.” Moreover, said Fronczak, “by proper therapeutic measures the disabilities gradually disappear, as they have in Mr. Roosevelt’s case.”

9While Roosevelt campaigned on the issues, Farley took the attack directly to the Republicans. Appearing on a New York radio station, he accused the GOP of waging a “whispering campaign” about FDR’s health. “In various parts of the country,” he declared, “are cropping up hateful stories in regard to our candidate’s physical and mental health.” In fact, Louis Howe had spent the past two years carefully keeping track of any and all news articles discussing Roosevelt’s health, firing off angry letters to refute those that questioned FDR’s physical fitness. Often the responses were written by the governor’s secretary, Guernsey Cross, such as when the

Newark Call claimed that Roosevelt’s “indispositions” had forced him to transfer some of his duties to Lieutenant Governor Herbert Lehman. “Governor Roosevelt has had no ‘indispositions’ and is in extremely good health,” wrote Cross, demanding a correction.

10 Similarly, when the

New Orleans Item reported that Roosevelt’s health had “much improved . . . in recent years” but ascribed his incapacity to “a tragic paralytic stroke,” Cross again demanded—and got—a published correction.

11 Sometimes Roosevelt responded personally, as when the

Danville (Virginia) Register published an item in December 1930 stating that his health “is still poor.” “My health is excellent,” he wrote the paper’s editor, “though as you know I still have to wear braces following infantile paralysis.”

12

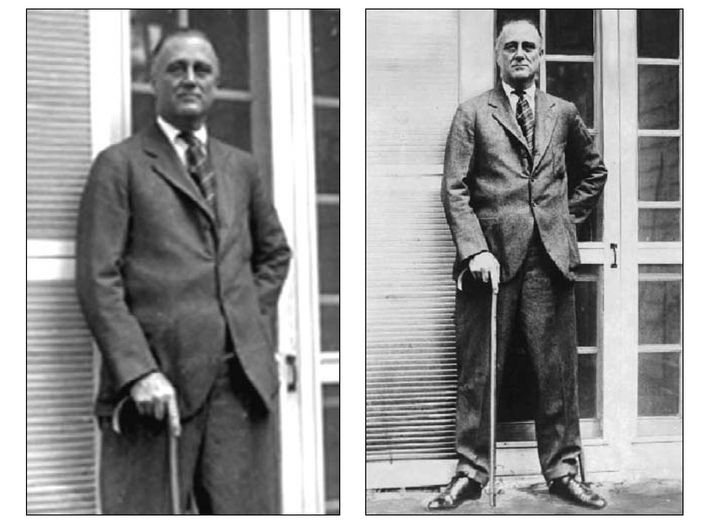

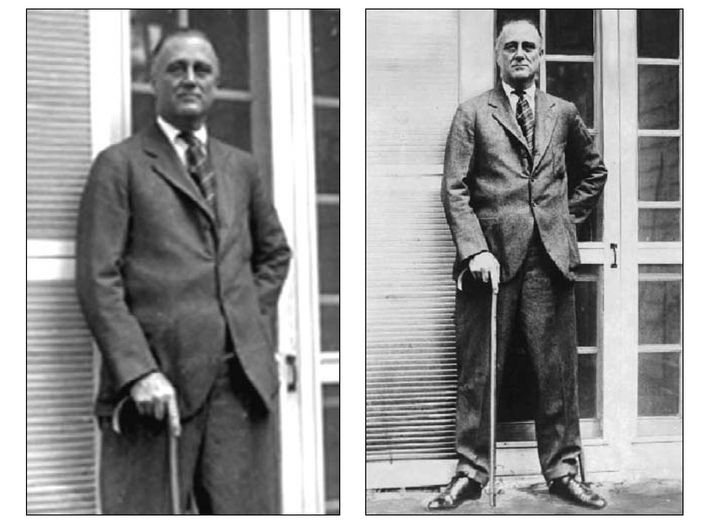

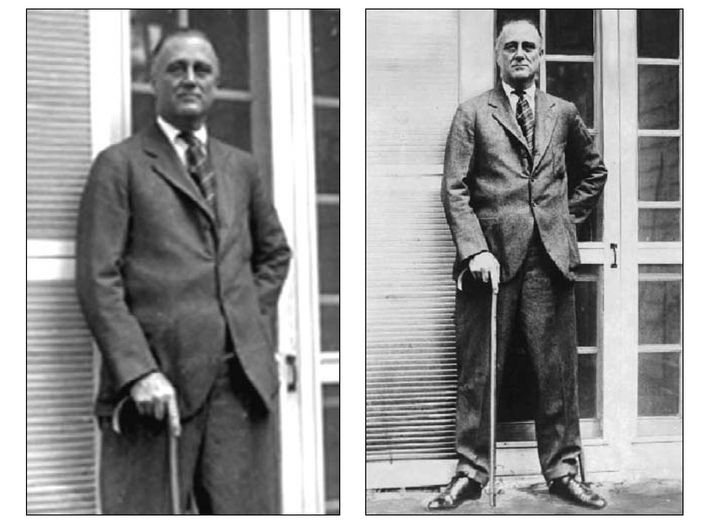

The lengths to which Roosevelt went to disguise his ongoing physical disability can be seen in these two photos. On the left is the one that was distributed to the press; it shows FDR confidently standing, needing only a cane for support. On the right is the original, uncropped picture, which clearly shows him using a second cane to precariously balance himself against a wall. Even with the two canes, he was incapable of standing or walking unassisted after 1921. (AP Worldwide)

As the presidential campaign picked up steam, Howe did not relent when it came to confronting suggestions of Roosevelt’s unfitness for office. Now, however, he had stronger ammunition than just his or the candidate’s denial. There was the 1930 insurance policy examination, of course, and another medical evaluation that had been conducted six months later in which, Howe reminded a radio audience, a trio of distinguished doctors had pronounced Roosevelt’s “lameness”—again, deliberately downplaying the true effect of FDR’s paralysis—to be “steadily getting better,” adding that it “had no more effect on his general condition than if he had a glass eye or was prematurely bald.”

13 Indeed, that examination declared that Roosevelt was showing “progressive recovery of power in his legs.” Moreover, it concluded, he “can walk all necessary distances and can maintain a standing position without fatigue”—a conclusion that was misleading at best, and flatly deceptive at worst, but like the earlier exam, was reported virtually without challenge in the press.

Yet that evaluation—as most FDR biographers now recognize—was a brilliant publicity stunt. It had originated in 1930 with Earle Looker, a freelance writer with connections to the Republican branch of the Roosevelt family. A letter from Looker to Eleanor Roosevelt in December 1930 disclosed his plans, already well under way, to write a book about FDR for use in the upcoming campaign. His unidentified backers, Looker informed Eleanor, “understand exactly what I have in mind” and “are so practically and enthusiastically for you and with me.”

14 What he had in mind, he later wrote, was a “challenge” to Roosevelt to allow a complete and independent medical examination of his health. The challenge was issued in a “brutal” letter he sent to FDR on February 23, 1931, and which was accepted five days later, with Roosevelt’s promise of complete cooperation “without censorship from me.” Not surprisingly, Looker’s account made no mention of his earlier correspondence with Eleanor, or that his backers, far from being critical Republicans, actually were “enthusiastically” supporting Roosevelt. As a result, he would later falsely claim, the letter demonstrated clearly that “I belonged to the opposition.”

Looker arranged for three prominent physicians—Samuel W. Lambert, former dean of Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons; Russell A. Hibbs, a prominent orthopedist; and Foster Kennedy, the chief neurologist at Bellevue Hospital—to examine Roosevelt at his home on April 29. Their findings were featured in an article Looker wrote for the July 25 issue of the popular weekly magazine

Liberty, under the title “Is Franklin D. Roosevelt Physically Fit to Be President?” and their conclusion was an unambiguous yes.

pThe article itself was written in a highly melodramatic style typical of the times with clearly embellished quotations: “Do I understand,” FDR asks at one point, “that as a Republican you are making a political thrust, with the thought that any admissions I might make will be used against me and my party?” Yet the piece was surprisingly candid about the extent of Roosevelt’s disability, concluding at one point that “his legs [are] not much good to him.” Significantly, it also included two photographs that would never be published again in FDR’s lifetime: one showing him in a chair in his office, his leg braces clearly visible (after he became president, they were painted black to ensure they could not be seen in any photo), and the other—even more remarkable—in which he sat in a bathing suit by the swimming pool at Warm Springs, making no effort to hide his visibly atrophied legs.

15 Even before the issue hit the stands, Howe had sent thousands of copies of the article to Democratic political officials and previously skeptical journalists.

16 Jim Farley pronounced the piece “a corker,” adding that it “answers fully [a] question that was put to me many times.”

Unlike the insurance exam six months earlier, the three doctors Looker hired did not release their specific findings (in fact, they did not become public until five years after Roosevelt’s death). Had they done so, at least two of the test results might have raised some eyebrows. FDR’s blood pressure reading was 140/100, a significant elevation over his 128/82 reading from the previous October (a normal level for a man of forty-nine was 120/80) and certainly cause for concern. Moreover, his EKG tracing was abnormal, suggesting enlargement of the left side of the heart and a decreased blood flow—both signs of incipient hypertensive cardiovascular disease.

17qLooker’s account did not go entirely unchallenged. Indeed, there were suspicions in some quarters that both the piece, and the medical appraisal on which it was based, were less than impartial. The

Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican published Looker’s denial that he was “hired by politicians to hush a whispering campaign.” Looker insisted that “the topic was dug up by him and no one else” and added his denial that he’d received “any financial compensation from Roosevelt, the Democratic party or anyone else.” In fact, the paper reported, “Mr. Looker himself paid for the medical examination.”

18But Looker’s private correspondence with Roosevelt, as demonstrated by historians David W. Houck and Amos Kiewe, tells an entirely different story. “Well, sir,” he wrote FDR, “we got away with the

Liberty article, despite all obstacles,” noting that “at least seven and a half million readers are sure you are physically fit!” He sent an even more revealing letter after the

Springfield Republican interview appeared: “The question of who paid for the physical examination was, and still is, between us, frightfully embarrassing.” Nonetheless, wrote Looker, “it had to be answered as I answered it.”

19 The implication—that Roosevelt actually underwrote the cost of the exam—is clear. Looker then discussed arrangements, already in the works, for him to pen a series of articles, in Roosevelt’s name, on world affairs for the McClure newspaper syndicate. “The fact that I am the ‘ghost-writer’ is secret,” Looker reminded FDR.

20Looker eventually expanded the

Liberty article into a full-length campaign biography titled

This Man Roosevelt, which discussed FDR’s health in glowing, but highly inaccurate, terms. Typical was this account: “I walked with him many times from the entrance hall into the Capitol, some fifty paces. . . . Walking some twenty paces more from the desk, he eases himself into his big Governor’s chair and flexes his leg braces so that his knees bend under the edge of his desk. He seems unfatigued.” In fact, wrote Looker, “the only reason for his braces is to insure his knees locking.”

21Looker’s efforts did not silence the whispers about Roosevelt’s health, but they went a long way toward discrediting them. And the candidate himself, hoping to emphasize his fitness and vitality, conducted a very public and vigorous campaign in which he traveled over 25,000 miles by train, despite the very real risk that he might fall in public. With the Depression showing no signs of abating and other developments—particularly the deadly rout by troops of the so-called Bonus Army of veterans in Washington, D.C.—working against Hoover, the results were no surprise: Roosevelt was elected in a landslide with 57 percent of the vote, carrying 42 of the 48 states and winning 472 electoral votes to just 59 for Hoover.

Once the election was over, Roosevelt decided he had no further need of Earle Looker. “Things have moved fast in this week since November eighth,” FDR wrote the author, “and it has become perfectly clear to me that future articles—at least for a long time—are taboo.” Yet Looker continued to press Roosevelt—though for what isn’t exactly certain. Over the next year, he would complain that the press was dismissing him as a Roosevelt “apologist when the need arises.” “I get it in the neck for being loyal to you,” he wrote the president in November 1933, adding: “Hah! That is not a laugh.”

22Roosevelt’s dismissive reply is astonishing, given the immense help Looker had provided: “Dear Earle: ‘Hah! Hah!’ and again ‘Hah!’ said the duck laughing. However, being a practical business man, I suggest stirring up some Foreign controversy over your opus. This will sell a million copies. Yours in misery.”

23As the time for Roosevelt’s inaugural drew closer,

r the president-elect—his cabinet chosen, the plans for his dramatic first hundred days in office mostly set in place—embarked, not surprisingly, on his favorite form of relaxation: an eleven-day Caribbean sea cruise aboard financier Vincent Astor’s yacht, accompanied by a retinue of old Harvard and political friends. It was, he wrote his mother, “a marvelous rest—lots of air and sun,” adding that “I shall be full of health and vigor—the last holiday for many months.”

But upon landing in Miami on February 15, Roosevelt faced a wholly unexpected threat that might have ended his presidency before it even began. After speaking at a rally to 20,000 well-wishers at Bay Front Park, he sat in his car with Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak, a former Al Smith supporter who had met the president-elect in a bid to make political peace. Suddenly an Italian-born bricklayer named Giuseppe Zangara, standing some forty feet away, opened fire with a pistol. After the first shot, which struck an onlooker, two other crowd members—Lillian Johns Cross, the wife of a local doctor, who was standing in front of him, and Thomas Armour, a contractor, in the row behind—grabbed Zangara’s arm as he continued shooting. None of the five shots hit Roosevelt, but one struck Cermak, who was gravely wounded.

Roosevelt, with remarkable calm, immediately took charge, overruling a Secret Service order that the president-elect’s car immediately leave the scene. Without hesitation, he once again became “Dr. Roosevelt”:

I saw Mayor Cermak being carried. I motioned to have him put in the back of the car, which would be the first out [of the park]. . . . I put my left arm around him and my hand on his pulse, but I couldn’t find any pulse. He slumped forward. . . . After we had gone another block, Mayor Cermak straightened up and I got his pulse. It was surprising. For three blocks I believed his heart had stopped. I held him all the way to the hospital and his pulse constantly improved. That trip to the hospital seemed thirty miles long. I talked to Mayor Cermak nearly all the way. I said, “Tony, keep quiet—don’t move. It won’t hurt you if you keep quiet.”

24sThe assassination attempt actually bolstered Roosevelt’s political stature. He’d won election not so much on the force of his personality or his record as governor as much as the fact that, simply, he wasn’t Herbert Hoover at a time when Depression-weary voters desperately sought change in Washington. But doubts still remained about his capacity to seize the reins of government and lead the nation through the ever-worsening economic crisis. Now, FDR’s calm, measured response throughout the shooting, and the quick-thinking, yet commanding, way in which he immediately exerted control, actually boosted the nation’s morale and elevated Roosevelt’s standing, particularly the public’s perception of him as a take-charge leader.

25Thus it was on March 4, 1933, that millions of Americans, one in four of whom were now unemployed, and many more increasingly anxious over the virtual collapse of the nation’s banking system, cheered as they listened, either in person or over their radios, to the clarion sound of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s voice reassuring them, with perfect and dramatic timing, that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”