CHAPTER 16

The Next Deadly Secret

Franklin Delano Roosevelt was not the first president who, with the aid of his doctors, covered up life-threatening or debilitating illnesses; Grover Cleveland, Woodrow Wilson, and possibly Warren Harding had all done it before. Nor would he prove to be the last: Dwight Eisenhower’s doctors suppressed, at least for a while, the serious extent of his cardiac and gastrointestinal problems; John F. Kennedy’s physicians hid the fact that he had Addison’s disease, a failure of the adrenal glands, and that it was treated with regular injections of corticosteroids laced with amphetamines. And Lyndon Johnson’s secret operation to remove a skin cancer from his ankle was not disclosed until four years after his death.

Even in an era of greater White House transparency, top aides to Ronald Reagan carefully controlled the information that was given to the press following the 1981 assassination attempt in which he was critically wounded, again three years later when doctors removed a cancerous polyp from his colon, and once more in 1987, when he underwent a prostate operation. In the latter case, First Lady Nancy Reagan pointedly refused to make her husband’s team of surgeons available to the news media for questioning, though the nature of the surgery was not hidden.

1The shock of FDR’s death, the revelation that he’d been increasingly ill beforehand, and his succession by the still relatively unknown Truman, touched off concern in Congress that it was time to take a closer look at the process for filling a sudden vacancy in the White House. Over the next quarter-century, the procedure would undergo several substantive revisions. But, in the end, one key element remains unresolved: how to keep another president from successfully concealing, as Franklin Roosevelt did, such a deadly secret from the American people.

One month after FDR’s death, Representative A. S. Mike Monroney (D-Oklahoma) introduced a bill proposing the first substantive change in the order of presidential succession in more than half a century. But his bill was a complicated affair, calling for a special commission to work out a long-term solution.

2 So, on June 19, 1945, President Truman sent a special message to Congress outlining a proposed solution to be codified in legislation without waiting for a commission to investigate.

As originally written, the U.S. Constitution specified only that the vice president ascends to the presidency in the case of a vacancy; the document left to Congress the task of selecting a new chief executive in the absence of a vice president. At no time—either then or for the next two centuries—was it suggested that the president nominate a new vice president should a vacancy occur. In 1792, Congress passed its first law on succession, specifying that the vice president be followed in the line of succession by the president pro tempore of the Senate (usually the body’s senior member) and then the Speaker of the House. That was changed in 1886, five years after President James A. Garfield was assassinated and several months after Grover Cleveland’s first vice president, Thomas A. Hendricks, died suddenly. This persuaded Congress that the vice president should be succeeded in line for the presidency by the members of the cabinet, in order of seniority, based on when their respective departments had been officially established; this placed the secretary of state first in line.

But Truman now objected to this method, noting that “each of these Cabinet members is appointed,” which meant that “by reason of the tragic death of the late President, it now lies within my power to nominate the person who would be my immediate successor in the event of my own death or inability to act. I do not believe,” he added, “that in a democracy this power should rest with the Chief Executive.”

3Truman was not the first to argue, as he did that day, that “insofar as possible, the office of the President should be filled by an elective officer.” But that was precisely what he proposed to Congress, though with a significant difference from the 1792 law: Truman insisted that the Speaker of the House be placed ahead of the Senate’s president pro tempore in the line of succession.

His official reasoning was somewhat tortured: The Speaker, he said, is elected not only by voters in his own district but by the members of the House, who are “all the Representatives of all the people in the country.” According to Truman, this made the Speaker that elected official who “can be most accurately said to stem from the people themselves.”

4 This, he said, is because the entire House—unlike the Senate—is elected every two years; members of the Senate, Truman insisted, “are not as closely tied in by the electoral process to the people as are the members of the House.”

Actually, Truman had a more personal, and blatantly political, concern: He wanted his good friend Sam Rayburn of Texas

cq to be first in line to succeed him, rather than Senator Kenneth McKellar of Tennessee, a onetime New Dealer who had grown more conservative over the years (and would soon be involved in a fierce political fight with Truman over the renomination of David A. Lilienthal to head the Tennessee Valley Authority). But the president also recognized that, as the senior member of the Senate, the president pro tempore tended to be an elderly Southerner. In fact, McKellar just five months earlier had succeeded Senator Carter Glass of Virginia, who’d held the post until his retirement at age eighty-seven. As for Secretary of State Edward Stettinius, who was then first in line,

New York Times Washington bureau chief Arthur Krock noted that most Democratic officials did not believe the onetime General Motors executive and veteran New Deal bureaucrat “has had the public and political training essential to the Presidency.”

5In his message, Truman noted that during the impeachment proceedings against President Andrew Johnson in 1868, some had “suggested the possibility of a hostile Congress in the future seeking to oust a Vice President who had become President, in order to have the President Pro Tempore of the Senate become President,” which was one of the motives behind the 1886 change in the law. So he proposed another clause: No matter who succeeded a vice president who had become president, that person “should not serve any longer than until the next Congressional election, or until a special election [is] called for the purpose of electing a new President and Vice President.”

6crInitial reaction to Truman’s proposal was extremely positive, especially in Democratic circles; the

New York Times hailed it as “fundamentally sound.”

7 Within days, however, opposition began to develop, mostly on constitutional grounds, with some arguing that an amendment to the Constitution, rather than congressional legislation, was needed. Others in Congress suggested changes to Truman’s idea: One bill proposed reconvening the Electoral College from the previous election to choose a new president and vice president. And there was near-unanimous opposition to a limited term or special election; general agreement was that whoever succeeded to office should serve out the remainder of the current presidential term.

8Eventually, the objections—including fears that a hostile Congress might impeach the president and vice president in order to install the Speaker—were met and, on July 19, 1947, Truman signed into law a bill changing the order of succession; the legislation, Public Law 199, also specified that anyone succeeding the vice president to the Oval Office would serve until the next scheduled presidential election.

But there had been a significant change in the political landscape since his initial proposal: When Truman first suggested placing the Speaker directly in line behind the vice president, he noted that the House “usually . . . is in agreement politically with the Chief Executive”; on the other hand, the Senate—one-third of whose members are elected every two years—might “have a majority hostile to the policies of the President, and might conceivably fill the Presidential office with one not in sympathy with the will of the majority of the people.”

9 In 1946, however, the GOP had taken control of both houses of Congress—meaning that the two people now in line to replace Democrat Truman were Republicans: Speaker Joseph W. Martin and Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg.

Similarly, had this system still been effect during the Watergate scandal of the 1970s, when Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation in a bribery scandal was followed ten months later by that of President Richard Nixon, the two ousted Republicans would have been succeeded by a Democrat, House Speaker Carl Albert of Oklahoma. And right behind him was the archconservative and outspokenly racist president pro tempore of the Senate, James O. Eastland of Mississippi.

Further concerns about presidential health led to yet another change in the succession system. President Dwight Eisenhower suffered a massive heart attack in 1955, as did Senate Majority Leader and future President Lyndon B. Johnson.

cs In 1958, Eisenhower and Vice President Richard Nixon reached an informal agreement regarding what they would do if the president became unable to serve.

10 But theirs was a personal and unofficial understanding, not binding either on them or on their successors.

The assassination in 1963 of the youthful John F. Kennedy and his succession by Johnson, whose past cardiac problems

ct were well documented—and the fact that immediately following LBJ in line were the seventy-two-year-old Speaker of the House, John W. McCormack and eighty-six-year-old Senator Carl Hayden—spurred calls for another comprehensive look at the issue. Of particular concern this time was how to determine, as in Franklin Roosevelt’s case, whether a president was physically and/or mentally able to serve.

Earlier in the ’60s, Congress had considered a proposal in which the vice president would notify the chief justice of the Supreme Court of any suspected inability; the jurist would then appoint a civilian panel to evaluate the president. This was rejected on two grounds: Involving the Supreme Court violated the constitutionally mandated separation of powers, and the panel would lack public accountability. Similarly, Congress rejected assembling a panel of physicians to examine the president, saying that legally forcing a chief executive to undergo an exam would violate presidential dignity and that, if a medical emergency existed, it would delay immediate action.

11Finally, in 1966, Congress passed, and the states ratified, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment. This provided for the first time that in the case of a vacancy in the office, the president would name a new vice president, who would then be confirmed by majority vote in both houses of Congress. This provision has been utilized twice: when Gerald Ford succeeded Spiro Agnew in 1973, and when Ford then named Nelson A. Rockefeller to replace him following Nixon’s resignation.

(Ironically, this led to precisely the situation Truman had warned against nearly three decades earlier: America was led by a president and a vice president, neither of whom had been elected to those posts by the voters.)

The amendment also provided that a president can declare himself unable to “discharge the powers and duties of his office” by so notifying congressional leaders; he may reassume the presidency upon transmitting “a written declaration” of his fitness. This has been used several times in recent decades, as presidents who undergo medical procedures involving anesthesia, for example, have declared themselves temporarily unable to discharge their duties and turned power over to the vice president—though, significantly, this was not invoked following Reagan’s assassination attempt or during his colon surgery.

In case a president cannot recognize his inability to serve, the amendment specifies that the vice president, along with a majority of the cabinet or some other “body” specified by Congress, can declare him disabled and temporarily remove him from office. If the president disagrees with their judgment or later tries to reclaim the office without the backing of the vice president and a cabinet majority, the matter moves to Congress for a vote.

At first glance, the Twenty-Fifth Amendment seems sufficiently comprehensive to prevent the kind of situation under which Franklin Roosevelt and his doctors were able to hide his medical unfitness for the presidency. But, as Aaron Seth Kesselheim of Harvard University has written, there are a number of serious problems with the process. For one thing, no single event is needed to invoke its protection. And the power to put the disability procedure into motion remains with the executive branch—specifically, he noted, “under the control of the people most beholden to the President. . . . Those same people who must initiate the Twenty-Fifth Amendment procedure are those whose power it most likely affects.”

12 Though the process is spelled out and authorized in the nation’s guiding legal document, the notion that a vice president and cabinet actually might use it remains almost inconceivable: Doubtless there would be considerable fear, particularly in a case where the president’s disability was not undeniably clear, of the public seeing any such effort as a veritable coup d’état. Certainly no one in Roosevelt’s cabinet would ever have initiated, or even supported, such a process, despite their considerable and growing concern for his health.

Besides, as Kesselheim points out, the amendment has a fatal flaw: Nowhere does it require a medical evaluation of the president, meaning that any decision to forcibly remove him from power is an entirely political one. This was no oversight; Congress specifically rejected the idea of creating a panel of neutral physicians, deciding that the removal of a president involves ramifications beyond a simple medical diagnosis. Indeed, it does not even require the White House physician, let alone an independent doctor, to certify the president’s disability. Relying on the White House physician would be a dubious step, at best; while the relationship between president and doctor in recent years has become less intimate than that of FDR and Ross McIntire, who was a member of the president’s inner circle, those doctors invariably are drawn from the ranks of the military. They still have the dual problem of loyalty to their patient as well as to their commander in chief.

13How, then, to solve the problem? Some have proposed establishing an independent board of medical experts, serving specific terms, who could be called on when needed to examine the president and submit their findings to the vice president and the cabinet. But concerns have been raised about forcing the chief executive to undergo an examination by doctors not of his own choosing. Also, it is not clear how any disagreement within the panel would be resolved.

Others have proposed upgrading the office of White House physician to a formal position: This would still allow presidents to choose their own doctors, remove the conflict involving the commander in chief, and give the physician a stronger and more independent voice. But, notes Kesselheim, this might also drive a wedge between doctor and president, leading the latter not to confide fully in his physician and to withhold potentially dangerous symptoms.

It’s ironic that top government agencies, like the Central Intelligence Agency, the Pentagon, and the State Department, have no problem requiring those appointed to senior positions to undergo advance medical screenings—and by an independent board, not their own physicians. Franklin Roosevelt required such an examination, at the Lahey Clinic, of Joseph E. Davies before naming him ambassador to the Soviet Union. Yet no such requirement—save for preelection public pressure—obtains on a presidential candidate. And once the president takes office, no independent doctor or board exists to monitor his health, or to confirm the publicly announced results of his annual medical examinations.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt and his doctors kept the full extent of his serious medical problems from the American people and—until now—from the pages of history, as well. But as things now stand more than sixty years later, another president of the United States with a similar deadly secret can still keep it hidden. And that is the real peril of FDR’s deception: Franklin Roosevelt rolled the dice with history and—with the debatable exception of Yalta—won. The next similarly stricken president may not prove to be so lucky.

A page from the original reading copy that Roosevelt used while delivering his Yalta report to Congress on March 1, 1945. The page is annotated to show FDR’s many mistakes, brought about by left hemianopia, a visual deficit caused by a metastatic brain tumor. As part of the neurological examination to test for this problem, patients are asked to read a word such as “northwestern.” Affected patients ignore the left side of the word and read “western” or “stern.” The hour-long speech contained over a dozen instances of this type of word substitution, along with many other digressions due to his visual problem. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library [FDRL])

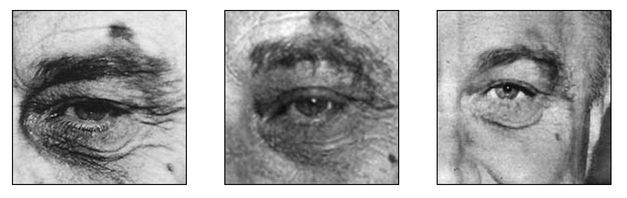

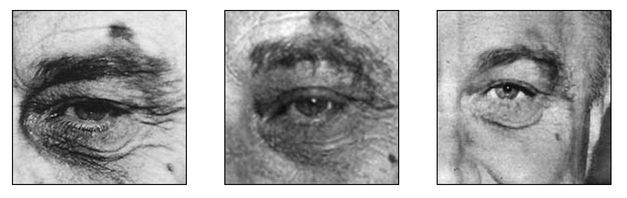

The lesion over Roosevelt’s left eye, which resembled a tiny sunspot in the early 1920s, gradually grew over the years until it had spread through the eyebrow and assumed the characteristics consistent with melanoma as utilized by present-day dermatologists. It reached its peak growth by the beginning of 1940, but then began to undergo radical changes. By December of that year, it had lightened considerably; by the time of Pearl Harbor, a year later, it was no more than a faint shadow. (FDRL)

Beginning in mid-1940, the expanding lesion over Roosevelt’s eye slowly began to disappear as a result of surgery, though his doctors made no mention of any procedures ever being performed on his face. (From left to right) January 1939: The lesion is seen at its greatest extent. (FDRL) August 1940: A fresh surgical scar is visible across the base of the eyebrow, with hairs combed across it. In addition, the small pigmented lesion just above the eyebrow has been replaced by a small diagonal surgical scar, and one of the two small pigmented lesions below the eye has been removed. (FDRL) 1942: Only a faint residual scar remains above the eye. (Yank magazine, April 27, 1945)

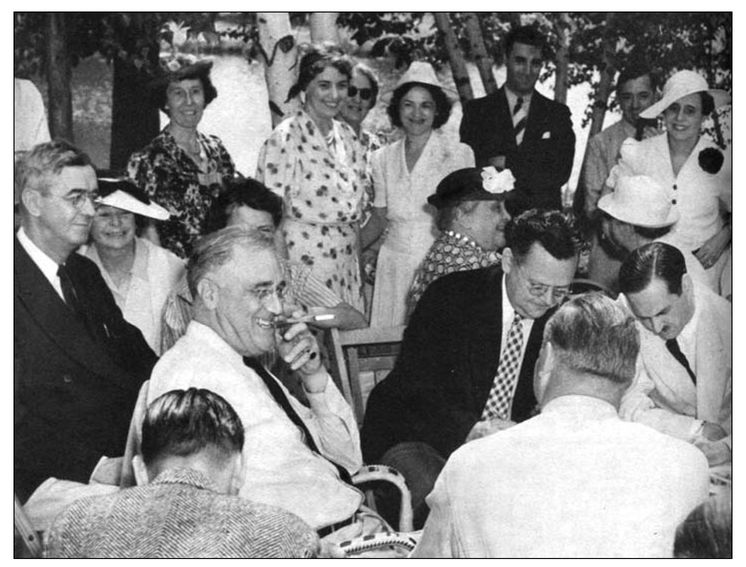

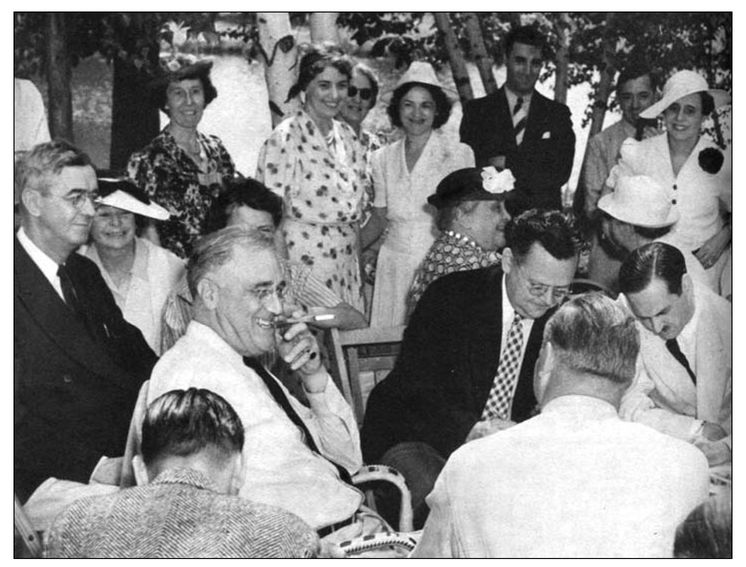

FDR conducts a press conference during a July 4, 1939, picnic at Val-Kill, Eleanor’s cottage down the road from his own family home at Hyde Park. Taking notes to his right, in the dark jacket, is the president’s journalistic bête noire, Walter Trohan of the Chicago Tribune. Next to him is Merriman Smith of United Press. Sitting behind the president is William Hassett, his confidential secretary, while FDR’s mother, Sara Delano Roosevelt, is immediately behind Trohan. The woman in the white patterned dress is Grace Tully, the president’s personal secretary; next to her in sunglasses is Marguerite “Missy” LeHand, who is widely believed to have had a long-standing romantic relationship with the president. (AP Worldwide)

The dramatic scene in Congress as President Roosevelt makes his final appearance there to deliver his post-Yalta report to the nation. For the first and only time, FDR publicly acknowledged his physical disability, apologizing for the “unusual posture of sitting down” because he wasn’t wearing “about ten pounds of steel around my legs.” (Bettmann/CORBIS)

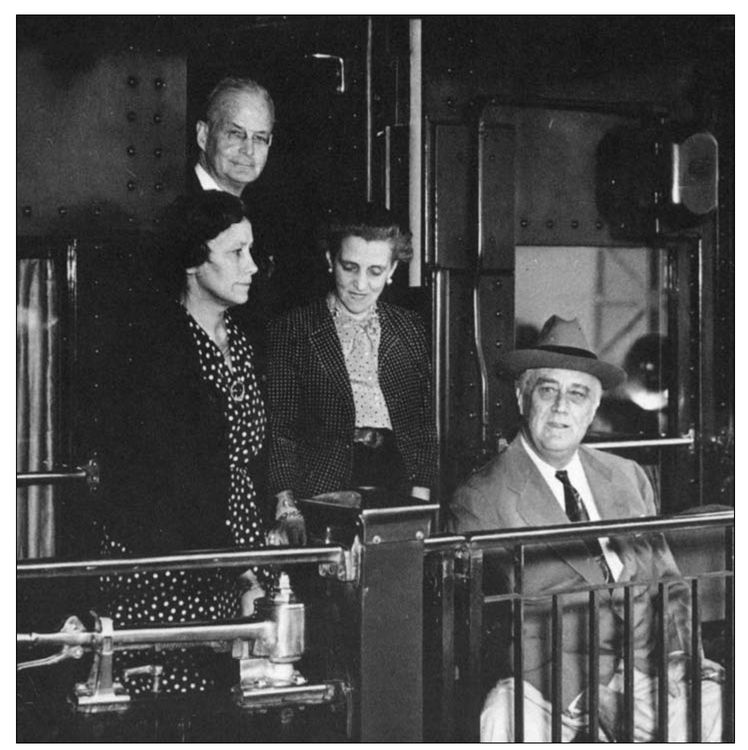

Roosevelt’s distant cousins, Margaret “Daisy” Suckley (left) and Laura “Polly” Delano, look on as the president is serenaded by an Army band onboard his personal railroad car, the Ferdinand Magellan, during a 1943 tour of military installations. Standing behind them is Harry Hooker, FDR’s former law partner and Daisy’s frequent escort at social occasions. Daisy’s diary, discovered only after her death in 1991, sheds dramatic new light on Roosevelt’s true feelings as ill health overtook him. (FDRL)

Louis Howe, Roosevelt’s political guru, who masterminded his political recovery from polio and his rise to the presidency; Press Secretary Stephen T. Early, who fiercely controlled how FDR was portrayed in the press; and Marvin McIntyre, who served at various times as the president’s appointments, traveling, and correspondence secretary, shortly after the first inauguration in 1933. (Bettmann/CORBIS)

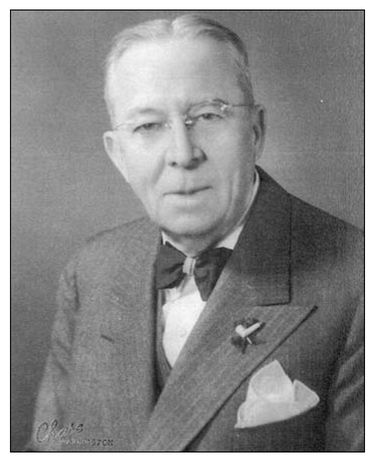

Dr. James Paullin, the Atlanta internist McIntire called in to confirm Howard Bruenn’s diagnosis that the president was suffering congestive heart failure, and who would arrive at FDR’s bedside at Warm Springs just moments before his death. (Courtesy Dr. Hal Raper)

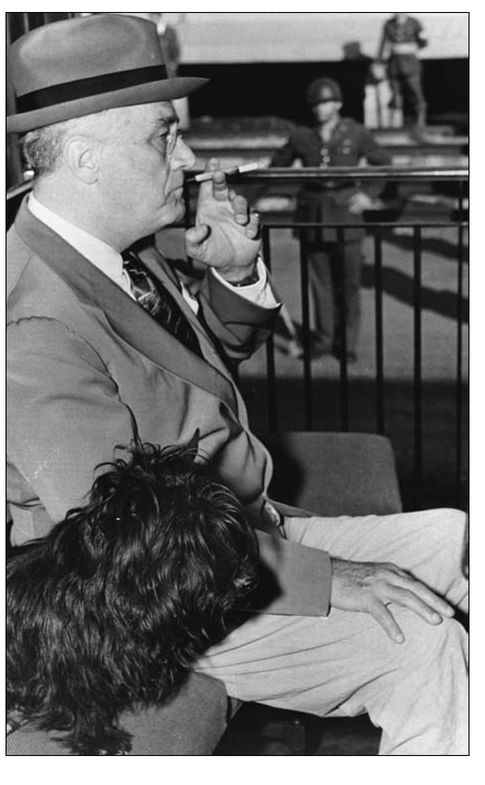

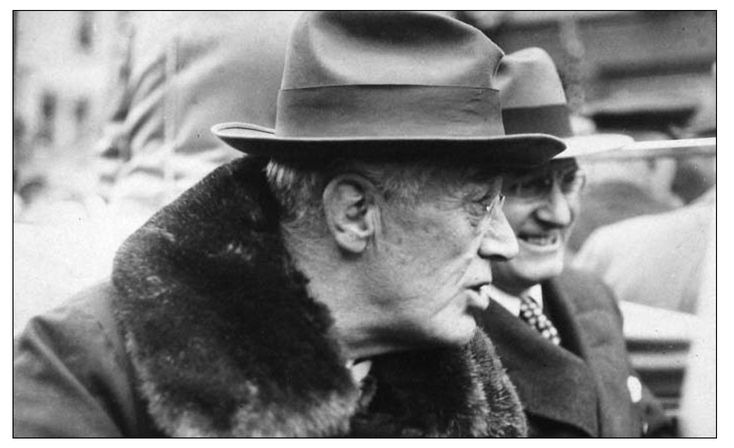

These photos, taken less than two years apart, document Roosevelt’s shocking and rapid physical deterioration. The president poses in late 1943 with his famous Scottish terrier, Fala (right). Barely a year later, a haggard and exhausted FDR (below), some thirty-five pounds below his normal weight, visits Newburgh, New York, on the last day of his final campaign in 1944. (Bettmann/Corbis, FDRL)