The domestic arrangements at Grimsetter left something to be desired. We were beset with failures in heating, fuel supply and transport. However, with a diet of baked beans and watery beer we would repair to the squadron dispersal, shut the doors and windows and build up a nice fug with the coal burning stoves.

Most of the squadron had read the famous inscription on a Northern Ireland tombstone. This read:

‘Where e’er you be

Let your wind go free.

’Twas holding it in

What kilt me.’

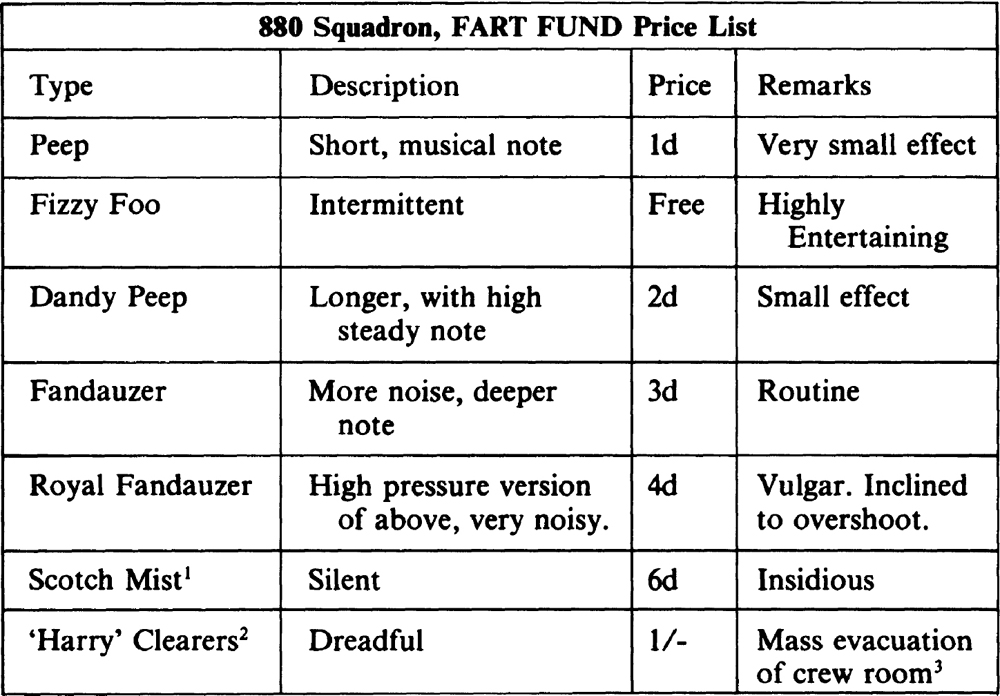

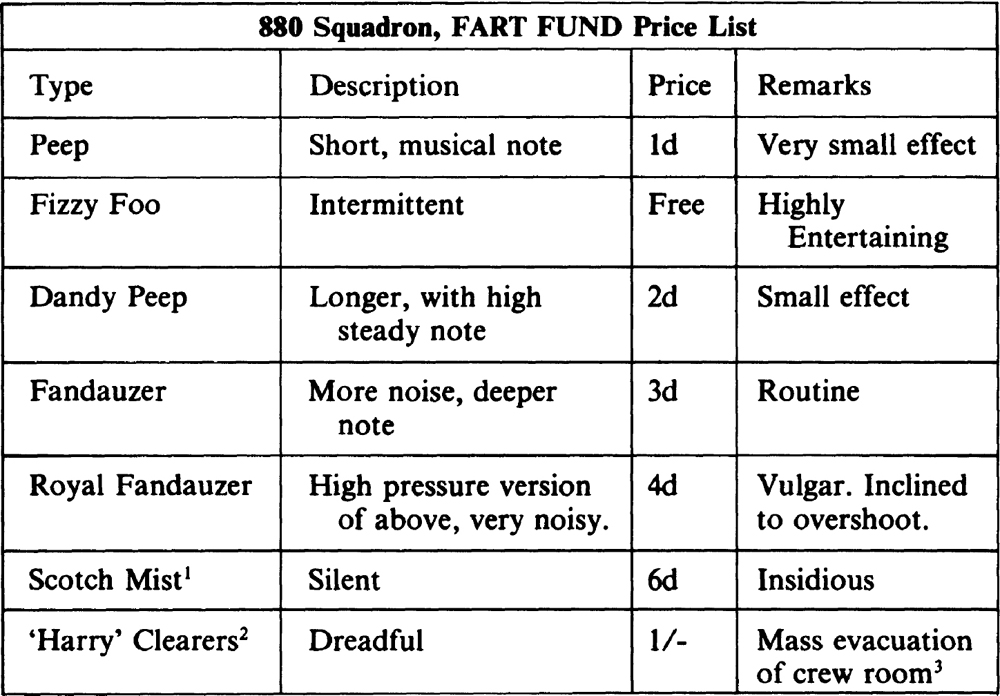

So the atmosphere could have grown a lettuce by lunchtime. Something had to be done. Dougy Yate devised a system of fines. The price list was as follows:

Notes:

1Duty Boy to judge, if no one owns up to items starred.

2Credit is allowed. Please enter fines against your name on list alongside.

3Patrons are asked not to evacuate the crew room unnecessarily as it cools the place down too much.

Dougy found that ‘Note (3)’ was necessary, as those who thought that the fund needed a boost would suddenly get up in a mass evacuation for insufficient reason. An unsuspecting type would then be left behind to pay.

In February we had a charming visit from Major Michael Scott and his C-Balls assistants who were joining Implacable. They arrived at dispersal in a desert-camouflaged Austin tourer, with the hood down, still bronzed from last year’s summer spent in the south of England.

Their Lordships had by now realised that they were losing their best surviving pilots for ever in making them continue to fly too long on operations. They therefore took ‘DC’ Richardson and Neville from us. However, ‘Crusty’ Pye and Bob Simpson (Willy’s younger brother) became replacement Flight Leaders for Richardson. C-H became the sixth on occasions, when he flew with us. We were also joined by Doug Graham (a 26-year-old married New Zealander), Len Simpson, Brian Wager, ‘Legs’ Lethem, Peter Dixon (another New Zealander) and ‘Paddy’ Seigne. These made our numbers up to 23. Two or three others did not make the grade. It was most unusual to refuse the selections made by NA2SL — the appointments division in the Admiralty for Fleet Air Arm aircrew — but time was short. ‘Below average’ pilots were unable to make the grade in the time available. They would have been a danger to themselves and to the rest of us, had they remained, for 880 Squadron was now adopting some very ‘dicey’ ground attack methods and these took a month or two to assimilate.

During our stay at Grimsetter from 15 January to 15 March 1945, we heard stories of the trials and tribulations of the Seafires in 24 Wing now in the Dutch East Indies in Indefatigable. This was only hearsay on the grapevine but it reminded us of the Salerno business and rang true. The Seafires had long lost their original Wing Leader, Buster Hallett (to 3 Wing for the ‘D’ Day operations at Lee-on-Solent), and their recent training in the UK had tended to suffer. We heard, in disgust that the two Seafire squadrons (887 and 894, Lt/Cdr ‘Shorty’ Dennison (later Andrew Thompson) and Lt/Cdr Jimmy Crossman) had been confined either to CAP over the Fleet, or to anti-submarine low-level reconnaissance, or to making practice Kamikaze attacks on the Fleet for the benefit of their gunners. Their morale had suffered and, at one stage, because they had only 17 aircraft left out of the 33 after only seven hours flying per pilot — mostly due to decklanding accidents — they had been stopped from flying altogether. Something better would have to be offered by 30 Wing if Admiral Vian, the AC1 to the Far Eastern Fleet, was going to put up with us when we arrived there. So we practised our ‘ground attack’ exercises.

Norman, Dougy and I had had much experience in 804 in manoeuvring fighter formations easily in the air. All that was necessary now was for us to use this formation and method of manoeuvre to position our Seafires for a simultaneous dive on ground targets, so that the strafing attack could be completed within about 20 seconds and before the enemy gunners could ‘remove their fingers’. Up to 16 of our Seafires would dive simultaneously from three different directions, and the enemy would not know which to aim at. After careful thought, we worked it out that 16 Seafires diving at once would have only one sixteenth of the gunners firing at each Seafire for one sixteenth of the time! In theory, we would therefore have about 60-100 times less chance of being shot down. Our formation dive, from at least three entirely different directions, would also reduce the time taken to re-form afterwards and so save fuel.

We practised these co-ordinated attacks — with radio silence — on every ‘target’ we could find. Islands in the middle of Scottish lochs, various ships — with prior permission — and our own airfield and dispersals. At times our aircraft crossed over each other in the pullout of the dives. Of course there was bound to be danger from our own shells when we used our guns instead of the camera-guns. However, we reckoned that the risks from this were slight compared with the risk of coming down singly to zero feet on an airfield well alerted and defended by 200 guns or more. We naturally used a low level approach. This obvious precaution allowed us to approach unseen by the enemy radar or enemy lookouts. The climb up to the pushover height of 8,000 feet was left until the last possible moment to give no radar warning, so that the enemy gunners might still be asleep, be shaving, or be drinking Suki-Aki or whatever Japanese gunners do. It was matters such as this that made us in 880 feel special. Of course we were not special. We were just ordinary. But we thought we were special and that was half the battle. However, as far as I know, no one else used this form of attack. Our (actual) losses due to flak were one tenth of Corsair or Hellcat squadrons’ per operational sortie.

With Implacable capable of flying off at least 50 aircraft in one strike — more than two (British) carriers-worth heretofore — constant decklanding practice was essential. Knowing the poor reserves of fuel which Seafires had, take-offs, form-ups, returns and land-ons had to be done in the minimum of time.

We knew that decklanding accidents in Seafires were inevitable, and were a certainty when landings were made into the sun, in heavy rain, on a pitching deck, with exhausted pilots or with defective aircraft. The slightest thing would put the pilot ‘over the top’ in his battle with his nerves. Everything, therefore, had to be done by constant practice, to make the difficult stuff appear easy. The brain would then be better able to cope with the landing itself, the ‘impossible’ bit. (See Appendix 11.) We aimed at 20-second decklanding intervals. Charles Evans was always delighted if we made it. However, in order to keep to an average of ten seconds, some had to be within ten seconds of each other, with the barrier still down while the next chap was over the round-down. As it was Charles’ responsibility, he would always take a risk. It usually came off, but with half-a-second to spare sometimes.

Seafire Mark III take-offs were never a problem, for R. J. Mitchell had designed the Spitfire I for quick ‘scrambles’ and the Seafire LIII’s power/weight ratio was even higher. With a 30 knot wind, it leapt off the deck in a distance of 130 feet, with a minimum unstick speed of 58 knots! Even with a 90 gallon overload tank, we could still get airborne safely with a run of 180 feet in that windspeed, half the distance of the catapult runs of today.

While we were at Grimsetter, we had all 48 Seafires in the air at once. This must have been a ‘first’ for the FAA from a single carrier. With C-H fighting our administrative battles for us, Stuart and I could concentrate on the flying and it seemed to be paying off. Morale was higher each day.

One day the Wing was practising its ‘live’ dinghy drill in Scapa Flow with an ASR (Air/Sea Rescue) Walrus. The exercise needed a ‘baled-out’ pilot to be rescued from his dinghy in his Mae West. The Walrus had to land alongside the pilot, who would be using his distress flares, dye marker and mirrors — if there was any sun — for all he was worth. The Walrus would taxi past with one wing over the top of the dinghy. The dinghy occupant would then catch hold of the wing and be hoisted aboard the Walrus wing and then through the hatchway in the hull and flown back to the ship. Midshipman Ian Penfold of 880 Squadron had volunteered for this task in spite of a water temperature of four degrees Centigrade and with no immersion suit. We watched from the rescue launch, cheering from time to time. That night we drank to Penny and we sang ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow’. The high-domed Nissen hut wardroom was just the place for singing, with John Boak, the Canadian, at the piano.

Next day we did another of our 32 aircraft ‘Balbos’. This naturally involved formation take-offs in pairs, otherwise we would all have run out of fuel before we had time to form up and land.

I did not see the accident myself or even hear of it until I had landed, for we operated in r/t silence. Penny had ‘gone in’ on take-off. His aircraft had piled in at the end of the runway in flames. A vital piece of evidence showed us what had gone wrong.

A few days before his immersion, Penfold thought that he would go to Hatston and ask the stores department to renew his flying gloves. These were long, leather gauntlets with a zip fastener from the wrist to half way to the elbow. The zip had bust on his right glove and he wanted a new pair.

The Commander (S) at Hatston, having already refused us a pair of boots on occasion, had refused to give Penny a pair of gloves and had only offered him one in replacement. He would then have had a new glove on his right hand and a well worn soft and comfortable glove on his left, with a different pattern of ‘feel’ altogether. The stick forces in a Seafire were a matter of ounces, not pounds, and a gentle touch was essential for smooth flying. So Penny refused the new glove and continued with the old, the zip fastener of which would not zip up at all.

It was found that his right hand had jammed in the cockpit hood, held by the remains of his glove. While shutting the hood, sliding it forward from its leading edge with his right hand, the outflow of air through the gap between the windscreen and the forward part of the sliding hood had taken the unzipped part of his glove over the top of his hand and had jammed it in the hood as he closed it, imprisoning his hand and holding it in front of his face in the vital seconds after take-off. In formation, it was enough for Penny to lose control, and he hit the ground in the second or two when he could not see where he was going.

We all felt very angry and I felt particularly sad having to tell Penny’s parents, who came up for the funeral. He was such a lovely fellow.

By February 1945, most of us in 30 Wing, in 1771 Firefly Squadron and 828 Avenger Squadron were quite certain that our next stop would be alongside the Americans in the Pacific. It was obvious that our Seafires would be required for low level CAP against the expected hoards of Kamikazes. However, C-H wanted to be sure that we were also capable of joining in strikes as well as ‘ramrods’ — provided we could get a suitable long range tank for our Seafires — so it was necessary to practice fighter support with the Avengers and Barracudas. In spite of the recommendation — following my NAFDU trial a year previously — that formation corkscrewing and close escort of Avengers with Seafires was out of the question and that ‘area defence’, like the RAF, was the only feasible form of fighter defence for slow-moving, low altitude, strike aircraft, the Avengers still insisted on close escort. They wanted the reassurance of being able to look out of their aircraft and actually see us there. We could appreciate their viewpoint — with Zeros about — but we wanted to tell them of our difficulties too. We had all had experience of attempting to formate on 100 knot aircraft with our Seafires or Hurricanes — whose minimum safe flying speed was about 160-180 knots. It was very difficult indeed, even with very small numbers and in crystal clear weather. To attempt it in bad weather or through cloud with enemy fighters about, was madness.

Many of the strike squadrons were commanded by Observers. This was doubtless because the Observers had had a head start over the pilots in the FAA due to the Navy’s ‘foot in the door’ policy in the early thirties, where RN Observers were much more numerous than RN pilots. We sympathised with their job, of course and realised they were extremely brave men — being flown by someone in the front and unable to see where they were going. However, we were sceptical about their ability to lead a formation from the back seat and found little in common with them when we tried to explain our difficulties to the very few from other carriers that we managed to meet. Our difficulties were compounded still further when we found that nearly all Operations Officers in carriers were also Observers (ours in Implacable was ex-Dasher of Oran fame) and had not the smallest appreciation of a single-seat fighter pilot’s difficulties. However, if we were to be allowed to take part in any strikes at all in the Pacific, we were in honour bound to, at least, try a few practice strikes with the Avengers, before we left the UK.

All our practice strikes had so far taken place with Barracudas of 828 Squadron in Implacable. As usual, they led us into the nearest cloud — and that was that. However, we could at least meet the CO of 828 afterwards and apologise and give our reasons for our disappearance en route. In the case of much larger exercises involving other carriers’ strike aircraft, we could not meet them afterwards (or before, for that matter) to tell them of our difficulties. There was no ‘Air Group’ organisation, as in the RAF, and therefore nothing was done to remedy matters. We found that other carriers’ strike leaders were usually senior to our own, so that we could not meet them to tell them that we wished to give them ‘area support’ and ‘top cover’ and their ideas on close escort were a waste of time and effort. When we got to the Pacific and read the American equivalent of our Flight Deck, we learnt for the first time how they managed. They had such a large number of aircraft in each carrier — up to 110 each — that they could mount an entire strike, unsupported by any other carrier’s aircraft. In this way, they could brief and debrief their strike and escort aircrews and learn from their experience as time went on. In the case of the BPF, with only half the aircraft per carrier, strikes had to be made up from two or more carriers’ aircraft, with the ‘junior’ leaders totally ignorant of where their seniors might be going until they were on their way and had been briefed in the air, somehow.

We knew little of the command structure of the BPF, except that we knew that Admiral Vian was our AC 1 and that he had been having a difficult time with his Seafires in Indefatigable in January 1945 when he had received his first baptism of fire from the Japanese in the East Indies. Nevertheless, during the next three months, his carrier fleet had greatly contributed to the downfall of the Japanese Army and Navy in that area. It had destroyed one third of the Japanese Southern Pacific oil supply, with strikes on Medan, Soeni Gerong and the docks and General Motors works at Batavia and the Palembang oil refinery. This series of strikes, together with Japan’s lack of aircrew to replace their huge losses at the hands of the magnificent American carrier-borne fighters, contributed significantly to the Japanese retreat from their southern outlying island strongholds, one by one.

We heard of the Japanese new method of attack and how it had made our gunners even more trigger-happy and that life was getting even more difficult for the Seafires of 24 Wing in Indefatigable. If they chased Kamikazes to the bitter end, they got fired at. If they returned to the Fleet short of fuel — having chased a non-Kamikaze decoy out of sight to no purpose or perhaps even shot it down — they got fired at. Finally, if they stood by, strapped in their cockpits on the flightdeck, they got the personal attention of a complete Kamikaze in their cockpit.

From January-March 1945, 30 aircrew had been lost at Palembang and other operations in the East Indies. Nine of these losses of aircrew were left behind at Palembang and were subsequently beheaded by the Japanese. They had made their way to the rendezvous to be picked up, but fuel shortage dictated the Fleet’s retirement and the rescue Walrus was told to leave them behind. We had no illusions in 30 Wing about our fate if we were taken prisoner, all we hoped for was, that if we baled out, someone in the tradition of Admiral Troubridge and Nelson would stay behind and rescue us.

So that, as we sailed out of Scapa on 15 March 1945, Indefatigable had completed her East Indies strikes and was on the way to her next operation with a reinforced BPF, operating from Sydney. The new BPF’s task was to help the Americans in their onslaught on the fortress island of Okinawa. The operation was to be called ‘Iceberg’, and the BPF was under the seagoing command of Admiral Sir Bernard Rawlings in King George V, with Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser as overall, shore-bound C-in-C in Sydney and, of course, Admiral Vian as AC1 in command of the BPF carrier force.

The events leading up to Okinawa were these: in the preceding autumn, General MacArthur’s wish to make ‘a media’ return through the surf of the Philippines had led to a sea battle near Leyte in which most of the remaining Japanese seagoing fleet had been sunk or put out of action. The Japanese could neither understand their own plan nor that of the Americans, but as the latter had a far greater and more flexible carrier force and better communications, they prevailed in the end, inflicting immense air losses on the Japanese as well.

After this victory off Leyte Gulf, the Third Fleet under Admiral Halsey cleared away for ‘Iceberg’ — the attack on Okinawa. This island had been a Japanese possession since 1880. It was a vital step across Japan’s supply route to their possessions further south and east. It had to go. The secondary task given to the British in ‘Iceberg’ was to interdict the airfields on an island chain which also lay across the Japanese air reinforcement route from Japan to Okinawa itself — Sakashima Gunto. Each of the four main islands had an airfield which required to be flattened and kept that way throughout the expected short period that the American amphibious forces would take to capture the airfields on Okinawa. Once these airfields were in American hands they could be turned over to the USAAF and the new B29s, and some of the medium range bombers. All of these aircraft could reach the mainland of Japan from north to south and the way could be opened up for an Allied landing on the Japanese homelands in the autumn.

The BPF spent five weeks in Sydney harbour preparing for the new offensive in the Pacific, but when they left Sydney on 10 March for the north they still did not know exactly where they would be required. First they called in at Manus. This was an equatorial offshore island in the British Admiralty Group seized back from the Japanese by the Americans a year previously. By 15 March they had reached Ulithi, a further 2000 miles north. Here it was decided that the BPF should be under the command of Admiral Halsey rather than Admiral Kinkaid further south, as the British supply system could now cope with a 3500 mile supply line from Sydney far better than the Americans had first thought.

It was an enormous and unaccustomed task for the BPF to keep itself supplied at sea. Having been designed for Europe and without refrigeration or air-conditioning, and yet having promised Admiral King that it would not sponge upon the Americans — even for its supplies of aviation and fuel oil — Admiral Rawlings would be hard pressed to find a way. A British Fleet Train of 60 ships was therefore organised to carry out the task of supply. It was trundled north from Sydney in advance of the main force, the single journey itself taking a fortnight.

The southern end of this supply route ended in Sydney docks where the dockies were notoriously difficult. There were continuous go-slows and blackings and several ships had to sail half loaded. Mail, however, did not suffer, as it came via San Francisco, and morale was good even if general health among the BPF was not. The inevitable substitution of fresh food and vegetables with powdered (dehydrated) food and food in tins, took its toll early on in ‘Iceberg’ and the doctors could do little to stop dysentery. There was also an immense difference in the American aviator’s life style. (Appendix 12.) Often they carried an overbearing of 50 aviators so that if ill health struck they could continue at full throttle with their flying programmes. All their carriers were superbly air-conditioned throughout. Thus, when the Kamikaze onslaught at Okinawa delayed the capture of Okinawa for an unexpected week of flying, the BPF began to suffer from lack of aircrew, replacement aircraft and poor health. Nevertheless, the four British carriers — Indom, Vic, Indefat and either Illustrious or Formidable — flew 2500 sorties between them in 28 days flying. They lost 41 aircrew and needed 173 replacement aircraft at the end, having started with 225. Twenty-six aircraft were lost to flak, none to air combat and another 43 wrecked on deck by four hits by Kamikazes. The armoured decks of the British carriers could easily withstand the gentle 300 knot arrival of a Kamikaze complete with bomb, but this same arrival went right through the Americans’ decks, taking deck-parked and loaded aircraft down into the hangars with it. Explosions and fire amongst the Americans took their toll.

During ‘Iceberg’ the BPF claimed to have destroyed 100 aircraft on the ground in the target areas, but they were unable to interdict the airfields to prevent aircraft movements. Another lesson learned by the BPF — beside the near impossibility to close an airfield by spasmodic interdiction — was that the Japanese AA appeared to be aiming at the leaders of strafing and bombing attacks almost exclusively as they dived in steady lines, one after the other at their ground targets. Four out of the eight COs were killed as a result.

On 10 April we heard that the last of the giant Japanese battleships — Yamato — had been sunk, with only 170 survivors out of a crew of 3000. She had put to sea from Japan with a one-way supply of oil, intending to commit suicide like some mammoth and senseless Kamikaze. She failed to fire even one effective shot in the war, or against the 40 American aircraft which sank her. It appalled us to think we should soon be fighting such an enemy.

Such was the true picture of what we should find on our arrival in the Pacific, one tenth only of which we knew at the time.