CHAPTER 17

Assessing and Achieving Value in Health Care Information Systems

Virtually all the discussion in this book has focused on the knowledge and management processes necessary to achieve one fundamental objective: organizational investments in IT resulting in a desired value. That value might be the furtherance of organizational strategies, improvement in the performance of core processes, or the enhancement of decision making. Achieving value requires the alignment of IT with overall strategies, thoughtful governance, solid information system selection and implementation approaches, and effective organizational change.

Failure to achieve desired value can result in significant problems for the organization. Money is wasted. Execution of strategies is hamstrung. Organizational processes can be damaged.

This chapter carries the IT value discussion further. Specifically, it covers the following topics:

- The definition of IT-enabled value

- The IT project proposal

- Steps to improve value realization

- Why IT fails to deliver returns

- Analyses of the IT value challenge

DEFINITION OF IT-ENABLED VALUE

We can make several observations about IT-enabled value:

- IT value can be both tangible and intangible.

- IT value can be significant.

- IT value can be variable across organizations.

- IT value can be diverse across IT proposals.

- A single IT investment can have a diverse value proposition.

- Different IT investments have different objectives and hence different value propositions and value assessment techniques.

These observations will be discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Both Tangible and Intangible

Tangible value can be measured whereas intangible value is very difficult, perhaps practically impossible, to measure.

Some tangible value can be measured in terms of dollars:

- Increases in revenue.

- Reductions in labor costs: for example, through staff layoffs, overtime reductions, or shifting work to less expensive staff.

- Reductions in supplies needed: for example, paper.

- Reductions in maintenance costs for computer systems.

- Reductions in use of patient care services: for example, fewer lab tests are performed or care is conducted in less expensive settings.

Some tangible value can be measured in terms of process improvements:

- Fewer errors

- Faster turnaround times for test results

- Reductions in elapsed time to get an appointment

- A quicker admissions process

- Improvement in access to data

Some tangible value can be measured in terms of strategically important operational and market outcomes:

- Growth in market share

- Reduction in turnover

- Increase in brand awareness

- Increase in patient and provider satisfaction

- Improvement in reliability of computer systems

In contrast, intangible value can be very difficult to measure. The organization is trying to measure such things as

- Improving in decision making

- Improving in communication

- Improving in compliance

- Improving in collaboration

- Increasing in agility

- Becoming more state of the art

- Improving in organizational competencies—for example, becoming better at managing chronic disease

- Becoming more customer friendly

Significant

IT can be leveraged to achieve significant organization value. Some example studies are cited next.

A study that compared the quality of diabetes care between physician practices that used electronic health records and practices that did not found that the EHR sites had composite standards for diabetes care that were 35.1 percent higher than paper-based sites and had 15 percent better care outcomes (Cebul, Love, Jain, & Herbert, 2011).

EMC (a company that makes data storage devices and other information technologies) reported a reduction of $200 million in health care costs over ten years through the use of data analytics, lifestyle coaches, and remote patient monitoring to help employees manage health risks and chronic diseases (Mosquera, 2011).

A cross-sectional study of hospitals in Texas (Amarasingham, Plantinga, Diener-West, Gaskin, & Powe, 2009) found that higher levels of the automation of notes and patient records were associated with a 15 percent decrease in the adjusted odds of a fatal hospitalization. Higher scores in the use of computerized provider order entry (CPOE) were associated with 9 percent and 55 percent decreases in the adjusted odds of death for myocardial infarction and coronary artery bypass graft procedures, respectively. For all cases of hospitalization, higher levels of clinical decision-support use were associated with a 16 percent decrease in the adjusted odds of complications. And higher levels of CPOE, results reporting, and clinical decision support were associated with lower costs for all hospital admissions.

Variable

Even when they implement the same system, not all organizations experience the same value. As discussed earlier, organizational factors such as change management prowess and governance have a significant impact on an organization’s ability to be successful in implementing health information technology.

As an example of variability, two children’s hospitals implemented the same electronic health record (including CPOE) in their pediatric intensive care units. One hospital experienced a significant increase in mortality (Han et al., 2005), while the other did not (Del Beccaro, Jeffries, Eisenberg, & Harry, 2006). The hospital that did experience an increase in mortality noted that several implementation factors contributed to the deterioration in quality; specific order sets for critical care were not created, changes in workflow were not well executed, and orders for patients arriving via critical care transportation could not be written before the patient arrived at the hospital, delaying life-saving treatments.

Even when organizations have comparable implementation skill levels, the value achieved can vary because different organizations decide to focus on different objectives. For example, some organizations may decide to improve diabetes care, while others may emphasize the reduction in care costs. Hence, if an outcome is of modest interest to an organization and it devotes few resources to achieving that outcome, it should not be surprised if the outcome does not materialize.

Diverse across Proposals

Consider three proposals (real ones from a large integrated delivery system) that might be in front of organizational leadership for review and approval: a disaster notification system, a document imaging system, and an e-procurement system. Each offers a different type of value to the organization.

The disaster notification system would enable the organization to page critical personnel, inform them that a disaster—for example, a train wreck or biotoxin outbreak—had taken place, and tell them the extent of the disaster and the steps they would need to take to help the organization respond to the disaster. The system would cost $520,000. The value would be “better preparedness for a disaster.”

The document imaging system would be used to electronically store and retrieve scanned images of paper documents, such as payment reconciliations, received from insurance companies. The system would cost $2.8 million, but would save the organization $1.8 million per year ($9 million over the life of the system) due to reductions in the labor required to look for paper documents and in the insurance claim write-offs that occur because a document cannot be located.

The e-procurement system would enable users to order supplies, ensure that the ordering person had the authority to purchase supplies, transmit the order to the supplier, and track the receipt of the supplies. Data from this system could be used to support the standardization of supplies: that is, to reduce the number of different supplies used. Such standardization might save $500,000 to $3 million per year. The actual savings would depend on physician willingness to standardize. The system would cost $2.5 million.

These proposals reflect a diversity of value, ranging from “better disaster response” to a clear financial return (document imaging) to a return with such a wide potential range (e-procurement) that it could be a great investment (if you really could save $3 million a year) or a terrible investment (if you could save only $500,000 a year).

Diverse in a Single Investment

Picture archiving and communication systems (PACS) are used to store radiology (and other) images, support interpretation of images, and distribute the information to the physician providing direct patient care. These systems are an example of the diversity of value that can result from one IT investment. A PACS can

- Reduce costs for radiology film and the need for film librarians.

- Improve service to the physician delivering care, through improved access to images.

- Improve productivity for the radiologists and for the physicians delivering care (both groups reduce the time they spend looking for images).

- Generate revenue, if the organization uses the PACS to offer radiology services to physician groups in the community.

This one investment has a diverse value proposition; it has the potential to deliver cost reduction, productivity gains, service improvements, and revenue gains.

Different Analyses for Different Objectives

The Committee to Study the Impact of Information Technology on the Performance of Service Activities (1994), organized by the National Research Council, has identified six categories of IT investments in service industries, reflecting different objectives. The techniques used to assess IT investment value should vary by the type of objective that the IT investment intends to support. One technique does not fit all IT investments.

Infrastructure

IT investments may be for infrastructure that enables other investments or applications to be implemented and deliver desired capabilities. Examples of infrastructure are data communication networks, workstations, and clinical data repositories. A delivery system–wide network enables a large organization to implement applications to consolidate clinical laboratories, implement organization-wide collaboration tools, and share patient health data between providers.

It is difficult to quantitatively assess the impact or value of infrastructure investments because

- They enable applications. Without those applications, infrastructure has no value. Hence, infrastructure value is indirect and depends on application value.

- The allocation of infrastructure value across applications is complex. When millions of dollars are invested in a data communication network, it may be difficult or impossible to determine how much of that investment should be allocated to the ability to create delivery system–wide EHRs.

- A good IT infrastructure is often determined by its agility, its potency, and its ability to facilitate integration of applications. It is very difficult to assign return on investment numbers or any meaningful numerical value to most of these characteristics. What, for instance, is the value of being agile enough to speed up the time it takes to develop and enhance applications?

Information system infrastructure is as hard to evaluate as other organizational infrastructure, such as having talented, educated staff. As with other infrastructure,

- Evaluation is often instinctive and experientially based.

- In general, underinvesting can severely limit the organization.

- Investment decisions involve choosing between alternatives that are assessed for their ability to achieve agreed-upon goals. For example, if an organization wishes to improve security, it might ask whether it should invest in network monitoring tools or enhanced virus protection. Which of these investments would enable it to make the most progress toward its goal?

Mandated

Information system investment may be necessary because of mandated initiatives. Mandated initiatives might involve reporting quality data to accrediting organizations, making required changes in billing formats, or improving disaster notification systems. Assessing these initiatives is generally approached by identifying the least expensive and the quickest to implement alternative that will achieve the needed level of compliance.

Cost Reduction

Information system investments directed to cost reduction are generally highly amenable to return-on-investment (ROI) and other quantifiable dollar-impact analyses. The ability to conduct a quantifiable ROI analysis is rarely the question. The ability of management to effect the predicted cost reduction or cost avoidance is often a far more germane question.

Specific New Products and Services

IT can be critical to the development of new products and services. At times the information system delivers the new service, and at other times it is itself the product. Examples of information system–based new services include bank cash-management programs and programs that award airline mileage for credit card purchases. A new service offered by some health care providers is a personal health record that enables a patient to communicate with his or her physician and to access care guidelines and consumer-oriented medical textbooks.

The value of some of these new products and services can be quantifiably assessed in terms of a monetary return. These assessments include analyses of potential new revenue, either directly from the service or from service-induced use of other products and services. A return-on-investment analysis will need to be supplemented by techniques such as sensitivity analyses of consumer response. Despite these analyses, the value of this IT investment usually has a speculative component. This component involves consumer utilization, competitor response, and impact on related businesses.

Quality Improvement

Information system investments are often directed to improving the quality of service or medical care. These investments may be intended to reduce waiting times, improve the ability of physicians to locate information, improve treatment outcomes, or reduce errors in treatment. Evaluation of these initiatives, although quantifiable, is generally done in terms of service parameters that are known or believed to be important determinants of organizational success. These parameters might be measures of aspects of organizational processes that customers encounter and then use to judge the organization—for example, waiting times in the physician’s office. A quantifiable dollar outcome for the service of care quality improvement can be very difficult to predict. Service quality is often necessary to protect current business, and the effect of a failure to continuously improve service or medical care can be difficult to project.

Major Strategic Initiative

Strategic initiatives in information technology are intended to significantly change the competitive position of the organization or redefine the core nature of the enterprise. In health care it is rare that information systems are the centerpiece of a redefinition of the organization. However, other industries have attempted IT-centric transformations. Amazon is an effort to transform retailing. Schwab.com is an undertaking intended to redefine the brokerage industry through the use of the web. There can be an ROI core or component to analyses of such initiatives, because they often involve major reshaping or reengineering of fundamental organizational processes. However, assessing the ROIs of these initiatives and their related information systems with a high degree of accuracy can be very difficult. Several factors contribute to this difficulty:

- These major strategic initiatives usually recast the organization’s markets and its roles. The outcome of the recasting, although visionary, can be difficult to see with clarity and certainty.

- The recasting is evolutionary; the organization learns and alters itself as it progresses, over what are often lengthy periods of time. It is difficult to be prescriptive about this evolutionary process. Most accountable care organizations are confronting this phenomenon.

- Market and competitor responses can be difficult to predict.

IT value is diverse and complex. This diversity indicates the power of IT and the diversity of its use. Nonetheless, the complexity of the value proposition means that it is difficult to make choices between IT investments and also difficult to assess whether the investment ultimately chosen delivered the desired value or not.

THE IT PROJECT PROPOSAL

The IT project proposal is a cornerstone in examining value. Clearly, ensuring that all proposals are well crafted does not ensure value. To achieve value, alignment with organizational strategies must occur, factors for sustained IT excellence must be managed, budget processes for making choices between investments must exist, and projects must be well managed. However, the proposal (as discussed in Chapter Fifteen) does describe the intended outcome of the IT investment. The proposal requests money and an organizational commitment to devote management attention and staff effort to implementing an information system. The proposal describes why this investment of time, effort, and money is worth it—that is, the proposal describes the value that will result.

In Chapter Fifteen we also discussed budget meetings and management forums that might review IT proposals and determine whether a proposal should be accepted. In this section we discuss the value portion of the proposal and some common problems encountered with it.

Sources of Value Information

As project proponents develop their case for an IT investment, they may be unsure of the full gamut of potential value or of the degree to which a desired value can be truly realized. The organization may not have had experience with the proposed application and may have insufficient analyst resources to perform its own assessment. It may not be able to answer such questions as, What types of gains have organizations seen as a result of implementing an electronic health record (EHR) system? To what degree will IT be a major contributor to our efforts to streamline operating room throughput?

Information about potential value can be obtained from several sources (discussed in Appendix A). Conferences often feature presentations that describe the efforts of specific individuals or organizations in accomplishing initiatives of interest to many others. Industry publications may offer relevant articles and analyses. Several industry research organizations—for example, Gartner and the Advisory Board—can offer advice. Consultants can be retained who have worked with clients who are facing or have addressed similar questions. Vendors of applications can describe the outcomes experienced by their customers. And colleagues can be contacted to determine the experiences of their organizations.

Garnering an understanding of the results of others is useful but insufficient. It is worth knowing that Organization Y adopted computerized provider order entry (CPOE) and reduced unnecessary testing by X percent. However, one must also understand the CPOE features that were critical in achieving that result and the management steps taken and the process changes made in concert with the CPOE implementation.

Formal Financial Analysis

Most proposals should be subjected to formal financial analyses regardless of their value proposition. Several types of financial measures are used by organizations. An organization’s finance department will work with leadership to determine which measures will be used and how these measures will be compiled.

Two common financial measures are net present value and internal rate of return:

- Net present value is calculated by subtracting the initial investment from the future cash flows that result from the investment. The cash can be generated by new revenue or cost savings. The future cash is discounted, or reduced, by a standard rate to reflect the fact that a dollar earned one or more years from now is worth less than a dollar one has today (the rate depends on the time period considered). If the cash generated exceeds the initial investment by a certain amount or percentage, the organization may conclude that the IT investment is a good one.

- Internal rate of return (IRR) is the discount rate at which the present value of an investment’s future cash flow equals the cost of the investment. Another way to look at this is to ask, Given the amount of the investment and its promised cash, what rate of return am I getting on my investment? On the one hand, a return of 1 percent is not a good return (just as one would not think that a 1 percent return on one’s savings was good). On the other hand, a 30 percent return is very good.

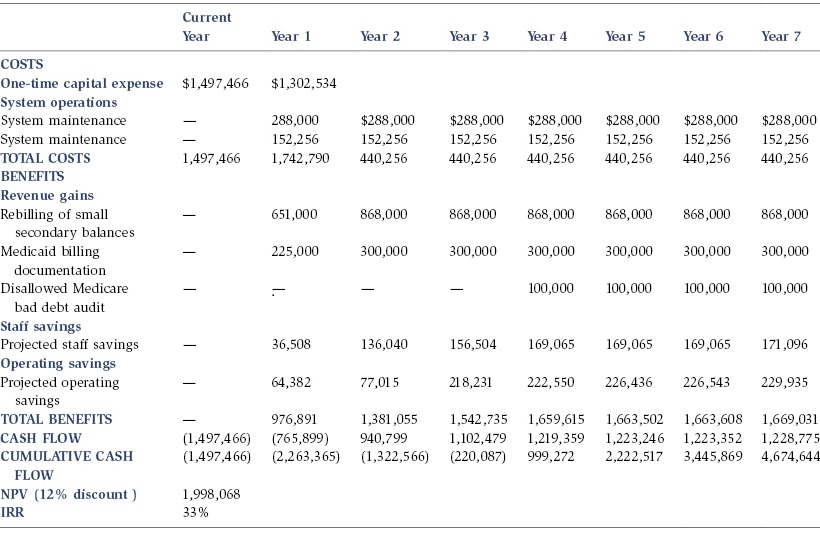

Table 17.1 shows the typical form of a financial analysis for an IT application.

Table 17.1. Financial analysis of a patient accounting document imaging system

Comparing Different Types of Value

Given the diversity of value, it is very challenging to compare IT proposals that have different value propositions. How does one compare a proposal that promises to increase revenue and improve collaboration to one that offers improved compliance, faster turnaround times, and reduced supply costs?

At the end of the day, judgment is used to choose one proposal over another. Health care executives review the various proposals and associated value statements and make choices based on their sense of organizational priorities, available monies, and the likelihood that the proposed value will be seen. These judgments can be aided by developing a scoring approach that allows leaders to apply a common metric across proposals. For example, the organization might decide to score each proposal according to how much value it promises to deliver in each of the following areas:

- Revenue impact

- Cost reduction

- Patient or customer satisfaction

- Quality of work life

- Quality of care

- Regulatory compliance

- Potential learning value

In this approach, each of these areas in each proposal is assigned a score, ranging from 5 (significant contribution to the area) to 1 (minimal or no contribution). The scores are then totaled for each proposal, and in theory, one picks those proposals with the highest aggregate scores. In practice, IT investment decisions are rarely that purely algorithmic. However, such scoring can be very helpful in sorting through complex and diverse value propositions:

- Scoring forces the leadership team to discuss why different members of the team assigned different scores—why, for example, did one person assign a score of 2 for the revenue impact of a particular proposal and another person assign a 4? These discussions can clarify people’s understandings of proposal objectives and help the team arrive at a consensus on each project.

- Scoring means that the leadership team will have to defend any decision not to fund a project with a high score or to fund one with a low score. In the latter case, team members will have to discuss why they are all in favor of a project when it has such a low score.

The organization can decide which proposal areas to score and which not to score. Some organizations give different areas different weights—for example, reducing costs might be considered twice as important as improving organizational learning. The resulting scores are not binding, but they can be helpful in arriving at a decision about which projects will be approved and what value is being sought. (A form of this scoring process was displayed earlier in Figure 13.2).

Tactics for Reducing the Budget

Proposals for IT initiatives may originate from a wide variety of sources in an organization. The IT group will submit proposals, as will department directors and physicians. Many of these proposals will not be directly related to an overall strategy but may nevertheless be “good ideas” that if implemented would lead to improved organizational performance. So it is common for an organization to have more proposals than it can fund. For example, during the IT budget discussion, the leadership team may decide that although it is looking at $2.2 million in requests, the organization can afford to spend only $1.7 million, so $500,000 worth of requests must be denied. Table 17.2 presents a sample list of requests.

Table 17.2. Requests for new information system projects

| Community General Hospital | |

| Project Name | Operating Cost |

| TOTAL | $2,222,704 |

| Clinical portfolio development | 38,716 |

| Enterprise monitoring | 70,133 |

| HIPAA security initiative | 36,950 |

| Accounting of disclosure—HIPAA | 35,126 |

| Ambulatory Center patient tracking | 62,841 |

| Bar-coding infrastructure | 64,670 |

| Capacity management | 155,922 |

| Chart tracking | 34,876 |

| Clinical data repository | 139,902 |

| CRP research facility | 7,026 |

| Emergency Department data warehouse | 261,584 |

| Emergency Department order entry | 182,412 |

| Medication administration system | 315,323 |

| Order communications | 377,228 |

| Transfusion services replacement system | 89,772 |

| Wireless infrastructure | 44,886 |

| Next-generation order entry | 3,403 |

| Graduate medical education duty hours | 163,763 |

Reducing the budget in situations like this requires a value discussion. The leadership is declaring some initiatives to have more value than others. Scoring initiatives according to criteria is one approach to addressing this challenge.

In addition to such scoring, other assessment tactics can be employed, prior to the scoring, to assist leaders in making reduction decisions.

- Some requests are mandatory. They may be mandatory because of a regulation requirement (such as a new Medicare Rule) or because a current system is so obsolete that it is in danger of crashing—permanently—and it must be replaced soon. These requests must be funded.

- Some projects can be delayed. They are worthwhile, but a decision on them can be put off until next year. The requester will get by in the meantime.

- Key groups within IT, such as the staff who manage clinical information systems, may already have so much on their plate that they cannot possibly take on another project. Although the organization wants to do the project, it would be ill advised to do so now, and so the project can be deferred to next year.

- The user department proposing the application may not have strong management or may be experiencing some upheaval; hence, implementing a new system at this time would be risky. The project could be denied or delayed until the management issues have been resolved.

- The value proposition or the resource estimates, or both, are shaky. The leadership team does not trust the proposal, so it could be denied or sent back for further analysis. Further analysis means that the proposal will be examined again next year.

- Less expensive ways of addressing the problems cited in the proposal may exist, such as a less expensive application or a non-IT approach. The proposal could be sent back for further analysis.

- The proposal is valuable, and the leadership team would like to move it forward. However, the team may reduce the budget, enabling progress to occur but at a slower pace. This delays realizing the value but ensures that resources are devoted to making progress.

These tactics are routinely employed during budget discussions aimed at trying to get as much value as possible given finite resources.

Common Proposal Problems

During the review of IT investment proposals, organizational leadership might encounter several problems related to the estimates of value and the estimates of the resources needed to obtain the value. If undetected, these problems might lead to a significant overstatement of potential return. An overstatement, obviously, may result in significant organizational unhappiness when the value that people thought they would see never materializes and never could have materialized.

Fractions of Effort

Proposal analyses might indicate that the new IT initiative will save fractions of staff time; for example, that each nurse will spend fifteen minutes less per shift on clerical tasks. To suggest a total value, the proposal might multiply as follows (this example is highly simplified): 200 nurses × 15 minutes saved per 8-hour shift × 250 shifts worked per year = 12,500 hours saved. The math might be correct, and the conclusion that 12,500 hours will become available for doing other work such as direct patient care might also be correct. But the analysis will be incorrect if it then concludes that the organization would thus “save” the salary dollars of six nurses (assuming 2,000 hours worked per year per nurse).

Saving fractions of staff effort does not always lead to salary savings, even when there are large numbers of staff, because there may be no practical way to realize the savings—to, for example, lay off six nurses. If, for example, there are six nurses working each eight-hour shift in a particular nursing unit, the fifteen minutes saved per nurse would lead to a total savings of 1.5 hours per shift. But if one were then to lay off one nurse on a shift, it would reduce the nursing capacity on that shift by eight hours, damaging the unit’s ability to deliver care. Saving fractions of staff effort does not lead to salary savings when staff are geographically highly fragmented or when they work in small units or teams. It leads to possible salary savings only when staff work in very large groups and some work of the reduced staff can be redistributed to others.

Reliance on Complex Behavior

Proposals may project with great certainty that people will use systems in specific ways. For example, several organizations expect that consumers will use Internet-based quality report cards to choose their physicians and hospitals. However, few consumers actually rely on such sites. Organizations may expect that nurses will readily adopt systems that help them discharge patients faster. However, nurses often delay entering discharge transactions so that they can grab a moment of peace in an otherwise overwhelmingly busy day.

System use is often not what was anticipated. This is particularly true when the organization has no experience with the relevant class of users or with the introduction of IT into certain types of tasks. The original value projection can be thrown off by the complex behaviors of system users. People do not always behave as we expect or want them to. If user behavior is uncertain, the organization would be wise to pilot an application and learn from this demonstration.

Unwarranted Optimism

Project proponents are often guilty of optimism that reflects a departure from reality. Proponents may be guilty of any of four mistakes:

- They assume that nothing will go wrong with the project.

- They assume that they are in full control of all variables that might affect the project—even, for example, quality of vendor products and organizational politics.

- They believe that they know exactly what changes in work processes will be needed and what system features must be present, when what they really have, at best, are close approximations of what must happen.

- They believe that everyone can give full time to the project and forget that people get sick or have babies and that distracting problems unrelated to the project will occur, such as a sudden deterioration in the organization’s fiscal performance, and demand attention.

Decisions based on such optimism eventually result in overruns in project budgets and timetables and compromises in system goals. Overruns and compromises change the value proposition.

Shaky Extrapolations

Projects often achieve gains in the first year of their implementation, and proponents are quick to project that such gains will continue during the remaining life of the project. For example, an organization may see 10 percent of its physicians move from using dictation when developing a progress note to using structured, computer-based templates. The organization may then erroneously extrapolate that each year will see an additional 10 percent shift. In fact the first year might be the only year in which such a gain will occur. The organization has merely convinced the more computer facile physicians to change, and the rest of the physicians have no interest in ever changing.

Underestimating the Effort

Project proposals might count the IT staff effort in the estimates of project costs but not count the time that users and managers will have to devote to the project. A patient care system proposal, for instance, may not include the time that will be spent by dozens of nurses working on system design, developing workflow changes, and attending training. These efforts are real costs. They often lead to the need to hire temporary nurses to provide coverage on the inpatient care units, or they might lead to a reduced patient census because there are fewer nursing hours available for patient care. Such miscounting of effort understates the cost of the project.

Fairy-Tale Savings

IT project proposals may note that the project can reduce the expenses of a department or function, including costs for staff, supplies, and effort devoted to correcting mistakes that occur with paper-based processes. Department managers will swear in project approval forums that such savings are real. However, when asked if they will reduce their budgets to reflect the savings that will occur, these same managers may become significantly less convinced that the savings will result. They may comment that the freed-up staff effort or supplies budgets can be redeployed to other tasks or expenses. The managers may be right that the expenses should be redeployed, and all managers are nervous when asked to reduce their budgets and still do the same amount of work. However, the savings expected have now disappeared.

Failure to Account for Postimplementation Costs

After a system goes live, the costs of the system do not go away. System maintenance contracts are necessary. Hardware upgrades will be required. Staff may be needed to provide enhancements to the application. These support costs may not be as large as the costs of implementation. But they are costs that will be incurred every year, and over the course of several years they can add up to some big numbers. Proposals often fail to adequately account for support costs.

STEPS TO IMPROVE VALUE REALIZATION

Achieving value from IT investments requires management effort. There is no computer genie that descends on the organization once the system is live and waves its wand and—shazzam!—value has occurred. Achieving value is hard work but doable work. Management can take several steps to realize value (Dragoon, 2003; Glaser, 2003a, 2003b). These steps are discussed in the sections that follow.

Make Sure the Homework Was Done

IT investment decisions are often based on proposals that are not resting on solid ground. The proposer has not done the necessary homework, and this elevates the risk of a suboptimal return.

Clearly, the track record of the investment proposer will have a significant influence on the investment decision and on leaders’ thinking about whether or not the investment will deliver value. However, regardless of the proposer’s track record, an IT proposal should enable the leadership team to respond with a strong yes to each of the following questions:

- Is it clear how the plan advances the organization’s strategy?

- Is it clear how care will improve, costs will be reduced, or service will be improved? Are the measures of current performance and expected improvement well researched and realistic? Have the related changes in operations, workflow, and organizational processes been defined?

- Are the senior leaders whose areas are the focus of the IT plan clearly supportive? Could they give the project proposal presentation?

- Are the resource requirements well understood and convincingly presented? Have these requirements been compared to those experienced by other organizations undertaking similar initiatives?

- Have the investment risks been identified, and is there an approach to addressing these risks?

- Do we have the right people assigned to the project, have we freed up their time, and are they well organized?

Answering with a no, a maybe, or an equivocal yes to any of these questions should lead one to believe that the discussion is perhaps focusing on an expense rather than an investment.

Require Formal Project Proposals

It is a fact of organizational life that projects are approved as a result of hallway conversations or discussions on the golf course. Organizational life is a political life. While recognizing this reality, the organization should require that every IT project be written up in the format of a proposal and that each proposal should be reviewed and subjected to scrutiny before the organization will commit to supporting it. However, an organization may also decide that small projects—for example, those that involve less than $25,000 in costs and less than 120 person-hours—can be handled more informally.

Increase Accountability for Investment Results

Few meaningful organizational initiatives are accomplished without establishing appropriate accountability for results. Accountability for IT investment results can be improved by taking three major steps.

First, the business owner of the IT investment should defend the investment—for example, the director of clinical laboratories should defend the request for a new laboratory system and the director of nursing should defend the need for a new nursing system. The IT staff will need to work with the business owner to define IT costs, establish likely implementation time frames, and sort through application alternatives. The IT staff should never defend an application investment.

Second, as was discussed in Chapter Sixteen, project sponsors and business owners must be defined, and they must understand the accountability that they now have for the successful completion of the project.

Third, the presentation of these projects should occur in a forum that routinely reviews such requests. Seeing many proposals, and their results, over the course of time will enable the forum participants to develop a seasoned understanding of good versus not-so-good proposals. Forum members are also able to compare and contrast proposals as they decide which ones should be approved. A manager might wonder (and it’s a good question), “If I approve this proposal, does that mean that we won’t have resources for another project that I might like even better?” Examining as many proposals together as possible enables the organization to take a portfolio view of its potential investments.

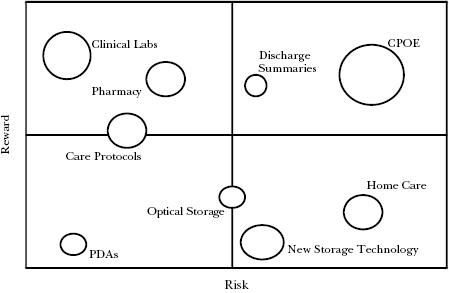

Figure 17.1 displays an example of a project investment portfolio represented graphically. The size of each bubble reflects the magnitude of a particular IT investment. The axes are labeled “reward” (the size of the expected value) and “risk” (the relative risk that the project will not deliver the value). Other axes may be used. One commonly used set of axes consists of “support of operations” and “support of strategic initiatives.”

Figure 17.1. IT investment portfolio

Source: Adapted from Arlotto & Oakes, 2003.

Diagrams such as the one in Figure 17.1 serve several functions:

- They summarize IT activity on one piece of paper, allowing leaders to consider a new request in the context of prior commitments.

- They help to ensure a balanced portfolio, promptly revealing imbalances such as a clustering of projects in the high-risk quadrant.

- They help to ensure that the approved projects cover an appropriate spectrum of organizational needs—for example, that projects are directed to revenue cycle improvement, to operational improvement, and to patient safety.

Conduct Postimplementation Audits

Rarely do organizations revisit their IT investments to determine if the promised value was actually achieved. They tend to believe that once the implementation is over and the change settles in, value will have been automatically achieved. This is unlikely.

Postimplementation audits can be conducted to identify value achievement progress and the steps still needed to achieve maximum gain. An organization might decide to audit two to four systems each year, selecting systems that have been live for at least six months. During the course of the audit meeting, these five questions can be asked:

- What goals were expected at the time the project investment was approved?

- How close have we come to achieving those original goals?

- What do we need to do to close the goal gap?

- How much have we invested in system implementation, and how does that compare to our original budget?

- If we had to implement this system again, what would we do differently?

Postimplementation audits assist value achievement by

- Signaling leadership interest in ensuring the delivery of results

- Identifying steps that still need to be taken to ensure value

- Supporting organizational learning about IT value realization

- Reinforcing accountability for results

Celebrate Value Achievement

Business value should be celebrated. Organizations usually hold parties shortly after applications go live. These parties are appropriate; a lot of people worked very hard to get the system up and running and used. However, up and running and used does not mean that value has been delivered. In addition to go-live parties, organizations should consider business value parties; celebrations conducted once the value has been achieved—for example, a party that celebrates the achievement of service improvement goals. Go-live parties alone risk sending the inappropriate signal that implementation is the end point of the IT initiative. Value delivery is the end point.

Leverage Organizational Governance

The creation of an IT committee of the board of directors can enhance organizational efforts to achieve value from IT investments. At times the leadership team of an organization is uncomfortable with some or all of the IT conversation. Board members may not understand why infrastructure is so expensive or why large implementations can take so long and cost so much. They may feel uncomfortable with the complexity of determining the likely value to be obtained from IT investments. The creation of a subcommittee made up of the board members most experienced with such discussions can help to ensure that hard questions are being asked and that the answers are sound.

Shorten the Deliverables Cycle

When possible, projects should have short deliverable cycles. In other words, rather than asking the organization to wait twelve or eighteen months to see the first fruits of its application implementation labors, make an effort to deliver a sequence of smaller implementations. For example, one might conduct pilots of an application in a subset of the organization, followed by a staged rollout. Or one might plan for serial implementation of the first 25 percent of the application features.

Pilots, staged rollouts, and serial implementations are not always doable. Where they are possible, however, they enable the organization to achieve some value earlier rather than later, support organizational learning about which system capabilities are really important and which were only thought to be important, facilitate the development of reengineered operational processes, and create the appearance (whose importance is not to be underestimated) of more value delivery.

Benchmark Value

Organizations should benchmark their performance in achieving value against the performance of their peers. These benchmarks might focus on process performance—for example, days in accounts receivable or average time to get an appointment. An important aspect of value benchmarking is the identification of the critical IT application capabilities and related operational changes that enabled the achievement of superior results. This understanding of how other organizations achieved superior IT-enabled performance can guide an organization’s efforts to continuously achieve as much value as possible from its IT investments.

Communicate Value

Once a year the information technology department should develop a communication plan for the twelve months ahead. This plan should indicate which presentations will be made in which forums and how often IT-centric columns will appear in organizational newsletters. The plan should list three or so major themes—for example, specific regional integration strategies or efforts to improve IT service—that will be the focus of these communications. Communication plans try to remedy the fact that even when value is being delivered, most people in the organization may not be fully aware of it.

WHY IT FAILS TO DELIVER RETURNS

It is not uncommon to hear leaders of health care organizations complain about the lack of value obtained from IT investments. These leaders may see IT as a necessary expense that must be tightly controlled rather than as an investment that can be a true enabler. New health care managers often walk into organizations where the leadership mind-set features this set of conclusions:

- The magnitude of the organization’s IT operating and capital budgets is large. IT operating costs may consume 3 percent of the total operating budget, and IT capital may claim 15 to 30 percent of all capital. Although 3 percent may appear small, it can be the difference between a negative operating margin and a positive margin. A 15 to 30 percent IT consumption of capital invariably means that funding for biomedical equipment (which can mean new revenue) and buildings (which can help the organization appear patient and staff friendly and can support the growth of clinical services) is diminished. IT can be seen as taking money away from “worthwhile initiatives.”

- The projected growth in IT budgets exceeds the growth in other budget categories. Provider organizations may permit overall operating budgets to increase at a rate close to the inflation rate (recently 3 to 4 percent). However, expenditures on IT often experience growth rates of 10 to 15 percent. At some point an organization will note that the IT budget growth rate may single-handedly lead to insolvency.

- Regardless of the amount spent, some members of the leadership team feel that not enough is being spent. Worthwhile proposals go unfunded every year. Infrastructure replacement and upgrades seem never ending: “I thought we upgraded our network two years ago. Are you back already?”

- It is difficult to evaluate IT capital requests. At times this difficulty is a reflection of a poorly written or fatuous proposal. However, it can be genuinely difficult to compare a proposal directed at improving service to one directed at improving care quality to one directed at increasing revenue to one needed to achieve some level of regulatory compliance.

- When asked to “list three instances over the last five years where IT investments have resulted in clear and unarguable returns to the organization,” leaders may return blank stares. However, the conversation may be difficult to stop when they are asked to “list three major IT investment disappointments that have occurred over the last five years.”

If the value from information technology can be significant, why does one hear these management concerns? There are several reasons why IT investments become simply IT expenses. The organization

- Fails to clearly link IT investments and organizational strategy.

- Asks the wrong question.

- Conducts the wrong analysis.

- Does not state its investment goals.

- Does not manage outcomes.

- Leaps to an inappropriate solution.

- Mangles the project management.

- Fails to learn from studies of IT effectiveness.

Failing to Clearly Link IT Investments and Organizational Strategy

The linkage between IT investments and the organization’s strategy was discussed in Chapter Thirteen. When strategies and investments are not aligned, the IT department, even if it is executing well, may be working on the wrong things or trying to support a flawed overall organizational strategy.

Linkage failures can occur because

- The organizational strategy is no more than a slogan or a buzzword with the depth of a bumper sticker, making any investment toward achieving it ill considered.

- The IT department thinks it understands the strategy but it does not, resulting in implementation of the IT version of the strategy rather than the organization’s version.

- The strategists (for a variety of reasons) will not engage in the IT discussion, forcing IT leaders to be mind readers.

- The linkage is superficial: for example, “Patient care systems can reduce nursing labor costs but we haven’t thought through how that will happen.”

- The IT strategy conversation is separated from the organizational strategy conversation, perhaps as a result of the creation of an information systems steering committee, reducing the likelihood of alignment.

- The organizational strategy evolves faster than IT can respond.

Asking the Wrong Question

Rarely should one ask the question, What is the ROI of a computer system? This makes as much sense as asking, What is the ROI of a chain saw? If one wants to make a dress, a chain saw is a waste of money. If one wants to cut down some trees, one can begin to think about the return on a chain saw investment. One will want to compare that investment to other investments, such as an investment in an ax. One will also want to consider the user. If the chain saw is to be used by a ten-year-old child, the investment might be ill advised. If the chain saw is to be used by a skilled lumberjack, the investment might be worth it.

An organization can determine the ROI of an investment in a tool only if it knows the task to be performed and the skill level of the participants who are to perform the task. Moreover, a positive ROI is not an inherent property of an IT investment. The organization has to manage a return into existence.

Hence, instead of asking, What is the ROI of a computer system? organizational leaders should ask questions such as these:

- What are the steps and investments, including IT steps and investments, that we need to take or make in order to achieve our goals?

- Which business manager owns the achievement of these goals? Does this person have our confidence?

- Do the cost, risk, and time frame associated with implementing this set of investments, including the IT investment, seem appropriate given our goals?

- Have we assessed the trade-offs and opportunity costs?

- Are we comfortable with our ability to execute?

Conducting the Wrong Analysis

There are times when determining ROI is the appropriate investment analysis technique. If a set of investments is intended to reduce clerical staff, an ROI can be calculated. However, there are times when an ROI calculation is clearly inappropriate. What is the ROI of software that supports collaboration? One could calculate the ROI, but it is hard to imagine an organization basing its investment decision on that analysis. Would an ROI analysis have captured the strategic value of the Amazon.com system or the value of social networking sites? Few strategic IT investments have impacts that are fully captured by an ROI analysis. Moreover, strategic impact is rarely fully understood until years after implementation. Whatever ROI analysis might have been done would have invariably been wrong.

As discussed earlier, the objective of the IT investment points to the appropriate approach to the analysis of its return. Sometimes organizations apply financial techniques such as internal rate of return in a manner that is overzealous and ignores other analysis approaches. This misapplication of technique can clearly lead to highly worthwhile initiatives being deemed unworthy of funding.

Not Stating Investment Goals

Statements about the positive contributions the investment will make to organizational performance often accompany IT proposals. Statements about specific numerical goals for this improvement are less common. If the investment is intended to reduce medical errors, will it reduce errors by 50 percent or 80 percent or some other number? If it is intended to reduce claim denials, will it reduce them to 5 percent or 2 percent, and how much revenue will be realized as a result of this reduction?

Failure to be numerically explicit about goals can create three fundamental value problems:

- The organization may not know how well it performs now. If the current error rate or denial rate is not known, it is hard to believe that the leadership has studied the problem well enough to be fairly sure that an IT investment will achieve the desired gains. The IT proposal sounds more like a guess about what is needed.

- The organization may never know whether it got the desired value or not. If the proposal does not state a goal, the organization will never know whether the 20 percent reduction in errors it has achieved is as far as it can go or whether it is only halfway to its desired goal. It does not know whether it should continue to work on the error problem or whether it should move on to the next performance issue.

- It will be difficult to hold someone accountable for performance improvement when the organization is unable to track how well he or she is doing.

Not Managing Outcomes

Related to the failure to state goals is the failure to manage outcomes into existence. Once the project is approved and the system is up, management goes off to the next challenge, seemingly unaware that the work of value realization has just begun.

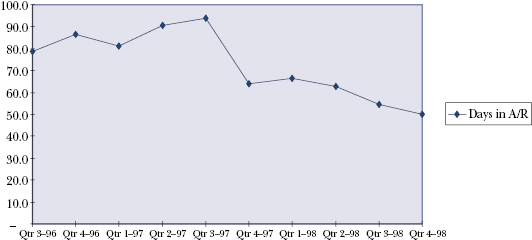

Figure 17.2 depicts a reduction in days in accounts receivable (AR) at a Partners HealthCare physician practice. During the interval depicted, a new practice management system was implemented. The practice did not see a precipitous decline in days in AR (a sign of improved revenue performance) in the time immediately following the implementation in the second quarter of 1997. The practice did see a progressive improvement in days in AR because someone was managing that improvement.

Figure 17.2. Days in accounts receivable before and after implementation of practice management system

If the gain in revenue performance had been an “automatic” result of the information system implementation, the practice would have seen a sharp drop in days in AR. Instead it saw a gradual improvement over time. This gradual change reflects that

- The gain occurred through day-in, day-out changes in operational processes, fine-tuning of system capabilities, and follow-ups in staff training.

- A person had to be in charge of obtaining this improvement. Someone had to identify and make operational changes, manage changes in system capabilities, and ensure that needed training occurred.

Leaping to an Inappropriate Solution

At times the IT discussion of a new application succumbs to advanced states of technical arousal. Project participants become overwhelmed by the prospect of using sexy new technology and state-of-the-art gizmos and lose their senses and understanding of why they are having this discussion in the first place. Sexiness and state-of-the-art-ness become the criteria for making system decisions.

In addition, the comparison of two alternative vendor products can turn into a features war. The discussion may focus on the number of features as a way of distinguishing products and fail to ask whether this numerical difference has any real impact on the value that is desired.

Both sexiness and features have their place in the system selection decision. However, they are secondary to the discussion that centers on the capabilities needed to effect specific performance goals. Sexiness and features may be irrelevant to the performance improvement discussion.

Mangling the Project Management

One guaranteed way to reduce value is to mangle the management of the implementation project. Implementation failures or significant budget and timetable overruns or really unhappy users—any of these can dilute value.

Among the many factors that can lead to mangled project management are these:

- The project’s scope is poorly defined.

- The accountability is unclear.

- The project participants are marginally skilled.

- The magnitude of the task is underestimated.

- Users feel like victims rather than participants.

- All the world has a vote and can vote at any time.

Many of these factors were discussed in Chapters Seven and Sixteen.

Failing to Learn from Studies of IT Effectiveness

Organizations may fail to invest in the IT abilities discussed in Chapter Fifteen, such as good relationships between the IT function and the rest of the organization and a well-architected infrastructure. This investment failure increases the likelihood that the percentage of projects that fail to deliver value will be higher than it should be.

ANALYSES OF THE IT VALUE CHALLENGE

The IT investment and value challenge plagues all industries. It is not a problem peculiar to health care. The challenge has been with us for fifty years, ever since organizations began to spend money on big mainframes. This challenge is complex and persistent, and we should not believe we can fully solve it. We should believe we can be better at dealing with it. This section highlights the conclusions of several studies and articles that have examined this challenge.

Factors That Hinder Value Return

The Committee to Study the Impact of Information Technology on the Performance of Service Activities (1994) found these major contributors to failures to achieve a solid return on IT investments:

- The organization’s overall strategy is wrong, or its assessment of its competitive environment is inadequate.

- The strategy is fine, but the necessary IT applications and infrastructure are not defined appropriately. The information system, if it is solving a problem, is solving the wrong problem.

- The organization fails to identify and draw together well all the investments and initiatives necessary to carry out its plans. The IT investment then falters because other changes, such as reorganization or reengineering, fail to occur.

- The organization fails to execute the IT plan well. Poor planning or less than stellar management can diminish the return from any investment.

Value may also be diluted by factors outside the organization’s control. Weill and Broadbent (1998) noted that the more strategic the IT investment, the more its value can be diluted. An IT investment directed to increasing market share may have its value diluted by non-IT decisions and events—for example, pricing decisions, competitors’ actions, and customers’ reactions. IT investments that are less strategic but have business value—for example, improving nursing productivity—may be diluted by outside factors—for example, shortages of nursing staff. And the value of an IT investment directed toward improving infrastructure characteristics may be diluted by outside factors—for example, unanticipated technology immaturity or business difficulties confronting a vendor.

The Investment-Performance Relationship

A study by Strassmann (1990) examined the relationship between IT expenditures and organizational effectiveness. Data from an Information Week survey of the top one hundred users of information technology were used to correlate IT expenditures per employee with profits per employee. Strassmann concluded that there is no overall obvious direct relationship between expenditure and organizational performance. This finding has been observed in several other studies (for example, Keen, 1997). It leads to several conclusions:

- Spending more on IT is no guarantee that the organization will be better off. There has never been a direct correlation between spending and outcomes. Paying more for care does not give one correspondingly better care. Clearly, one can spend so little that nothing effective can be done. And one can spend so much that waste is guaranteed. But moving IT expenditures from 2 percent of the operating budget to 3 percent of the operating budget does not inherently lead to a 50 percent increase in desirable outcomes.

- Information technology is a tool, and its utility as a tool is largely determined by the tool user and his or her task. Spending a large amount of money on a chain saw for someone who doesn’t know how to use one is a waste. Spending more money on tools for the casual saw user who trims an apple tree every now and then is also a waste. However, skilled loggers might say that if a chain saw blade were longer and the saw’s engine more powerful, they would be able to cut 10 percent more trees in a given period of time. The investment needed to enhance the loggers’ saws might lead to superior performance. Organizational effectiveness in applying IT has an enormous effect on the likelihood of a useful outcome from increased IT investment.

- Factors other than the appropriateness of the tool to the task also influence the relationship between IT investment and organizational performance. These factors include the nature of the work (for example, IT is likely to have a greater impact on bank performance than on consulting firm performance), the basis of competition in an industry (for example, cost per unit of manufactured output versus prowess in marketing), and an organization’s relative competitive position in the market.

The Value of the Overall Investment

Many analyses and academic studies have been directed to answering this broad question: How can an organization assess the value of its overall investments in IT? Assessing the value of the aggregate IT investment is different from assessing the value of a single initiative or other specific investment. And it is also different from assessing the caliber of the IT department. Developing a definitive, accurate, and well-accepted way to answer this question has so far eluded all industries and may continue to be elusive. Nonetheless there are some basic questions that can be asked in pursuit of answering the larger question. Interpreting the answers to these basic questions is a subjective exercise, making it difficult to derive numerical scores. Bresnahan (1998) suggests five questions:

- How does IT influence the customer experience?

- Do patients and physicians, for example, find that organizational processes are more efficient, less error prone, and more convenient?

- Does IT enable or retard growth? Can the IT organization support effectively the demands of a merger? Can IT support the creation of clinical product lines—for example, cardiology—across the integrated delivery system?

- Does IT favorably affect productivity?

- Does IT advance organizational innovation and learning?

IT as a Commodity

Carr (2003) has equated IT with commodities—soybeans, for example. Carr’s argument is that core information technologies, such as fast, inexpensive processors and storage, are readily available to all organizations and hence cannot provide a competitive advantage. Organizations can no more achieve value from IT than an automobile manufacturer can achieve value by buying better steel than a competitor does or a grocer can achieve value by stocking better sugar than a competitor does. In this view, IT, steel, and sugar are all commodities.

Responding to Carr’s argument, Brown and Hagel (2003) make three observations about IT value:

- “Extracting value from IT requires innovation in business practices.” (p. 110) If an organization merely computerizes existing processes without rectifying (or at times eliminating) process problems, it may have merely made process problems occur faster. In addition, those processes are now more expensive because there is a computer system to support. Providing appointment scheduling systems may not make waiting times any shorter or enhance patients’ ability to get an appointment when they need one.

All IT initiatives should be accompanied by efforts to materially improve the processes that the system is designed to support. IT often enables the organization to think differently about a process or expand its options for improving a process. If the process thinking is narrow or unimaginative, the value that could have been achieved will have been lost, with the organization settling for an expensive way to achieve minimal gain. For example, if Amazon had thought that the Internet enabled it to simply replace the catalogue and telephone as a way of ordering something, it would have missed ideas such as presenting products to the customer based on data about prior orders or enabling customers to leave their own ratings of books and music. - “IT’s economic impact comes from incremental innovations rather than from ‘big bang’ initiatives.” (p. 110) Organizations will often introduce very large computer systems and process change “all at once.” Two examples of such big bangs are the replacement of all systems related to the revenue cycle and the introduction of a new patient care system over the course of a few weeks.

Big bang implementations are very tricky and highly risky. They may be haunted by series of technical problems. Moreover, these systems introduce an enormous number of process changes affecting many people. It is exceptionally difficult to understand the ramifications of such change during the analysis and design stages that precede implementation. A full understanding is impossible. As a result, the implementing organization risks material damage. This damage destroys value. It may set the organization back, and even if the organization grinds its way through the disruption, the resulting trauma may make the organization unwilling to engage in future ambitious IT initiatives.

In contrast, IT implementations (and related process changes) that are more incremental and iterative reduce the risk of organizational damage and permit the organization to learn. The organization has time to understand the value impact of phase n and then can alter its course before it embarks upon phase n + 1. Moreover, incremental change leads the organization’s members to understand that change, and realizing value, are never-ending aspects of organizational life rather than things to be endured every couple of years. - “The strategic impact of IT investments comes from the cumulative effect of sustained initiatives to innovate business practices in the near term.” (p. 111) If economic value is derived from a series of thoughtful, incremental steps, then the aggregate effect of those steps should be a competitive advantage. Most of the time, organizations that wind up dominating an industry do so through incremental movement over the course of several years (Collins, 2001). This observation is consistent with our view in Chapter Fourteen. Persistent innovation by a talented team, over the course of years, will result in significant strategic gains. The organization has learned how to improve itself, year in and year out. Strategic value is a marathon. It is a long race that is run and won one mile at a time.

SUMMARY

IT value is complex, multifaceted, and diverse across and within proposed initiatives. The techniques used to analyze value must vary with the nature of the value.

The project proposal is the core means for assessing the potential value of an IT initiative. IT proposals have a commonly accepted structure. And approaches exist for comparing proposals with different types of value propositions. Project proposals often present problems in the way they estimate value—for example, they may unrealistically combine fractions of effort saved, fail to appreciate the complex behavior of system users, or underestimate the full costs of the project.

Many factors can dilute the value realized from an IT investment. Poor linkage between the IT agenda and the organizational strategy, the failure to set goals, and the failure to manage the realization of value all contribute to dilution.

There are steps that can be taken to improve the achievement of IT value. Leadership can ensure that project proponents have done their homework, that accountability for results has been established, that formal proposals are used, and that postimplementation audits are conducted. Even though there are many approaches and factors that can enhance the realization of IT-enabled value, the challenges of achieving this value will remain a management issue for the foreseeable future.

Health care organization leaders often feel ill equipped to address the IT investment and value challenge. However, no new management techniques are required to evaluate IT plans, proposals, and progress. Leadership teams are often asked to make decisions that involve strategic hunches (such as a belief that developing a continuum of care would be of value) about areas where they may have limited domain knowledge (new surgical modalities) and where the value is fuzzy (improved morale). Organizational leaders should treat IT investments just as they would treat other types of investments; if they don’t understand, believe, or trust the proposal, or its proponent, they shouldn’t approve it.

KEY TERMS

- Failure to deliver returns

- IT project proposals

- IT value

- Value realization

LEARNING ACTIVITIES

- Interview the CIO of a local health care provider or payer. Discuss how his or her organization assesses the value of IT investments and ensures that the value is delivered.

- Select two articles from a health care IT trade journal that describe the value an organization received from its IT investments. Critique and compare the articles.

- Select two examples of intangible value. Propose one or more approaches that an organization might use to measure each of those values.

- Prepare a defense of the value of a significant investment in an electronic health record system.

REFERENCES

Amarasingham, R., Plantinga, L., Diener-West, M., Gaskin, D. J., & Powe, N. R. (2009). Clinical information technologies and inpatient outcomes. Archives of Internal Medicine, 169(2), 108–114.

Arlotto, P., & Oakes, J. (2003). Return on investment: Maximizing the value of healthcare information technology. Chicago: Healthcare Information and Management Systems Society.

Bresnahan, J. (1998, July 15). What good is technology? CIO Enterprise, pp. 25–26, 28, 30.

Brown, J., & Hagel, J. (2003). Does IT matter? Harvard Business Review, 81, 109–112.

Carr, N. (2003). IT doesn’t matter. Harvard Business Review, 81, 41–49.

Cebul, R. D., Love, T. E., Jain, A. K., & Herbert, C. J. (2011). Electronic health records and the quality of diabetes care. New England Journal of Medicine, 365, 825–833.

Collins, J. (2001). Good to great. New York: HarperCollins.

Committee to Study the Impact of Information Technology on the Performance of Service Activities. (1994). Information technology in the service society. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Del Beccaro, M. A., Jeffries, H. E., Eisenberg, M. A., & Harry, E. D. (2006). Computerized provider order entry implementation: No association with increased mortality rates in an intensive care unit. Pediatrics, 118(1), 290–295.

Dragoon, A. (2003, August 15). Deciding factors. CIO, pp. 49–59.

Glaser, J. (2003a, March). Analyzing information technology value. Healthcare Financial Management, pp. 98–104.

Glaser, J. (2003b, September). When IT excellence goes the distance. Healthcare Financial Management, pp. 102–106.

Han, Y. Y., Carcillo, J. A., Venkataraman, S. T., Clark, R.S.B., Watson, R. S., Nguyen, T. C., Bayir, H., & Orr, R. A. (2005). Unexpected increased mortality after implementation of a commercially sold computerized physician order entry system. Pediatrics, 116(6), 1506–1512.

Keen, P. (1997). The process edge. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Mosquera, M. (2011). How PHRs boosted shareholder value at EMC. Government Health IT. Retrieved August 2011 from http://govhealthit.com/news/some-employers-say-phrs-cut-healthcare-costs

Ross, J., & Beath, C. (2002). Beyond the business case: New approaches to IT investment. MIT Sloan Management Review, 43(2), 51–59.

Ross, J. W., & Johnson, E. (2009). Prioritizing IT investments. Research Briefing, Vol. IX(3). Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Information Systems Research.

Strassmann, P. (1990). The business value of computers. New Canaan, CT: Information Economics Press.

Weill, P., & Aral, S. (2006). Generating premium returns on your IT investments. MIT Sloan Management Review, 47(2), 54–60.

Weill, P., & Broadbent, M. (1998). Leveraging the new infrastructure. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.