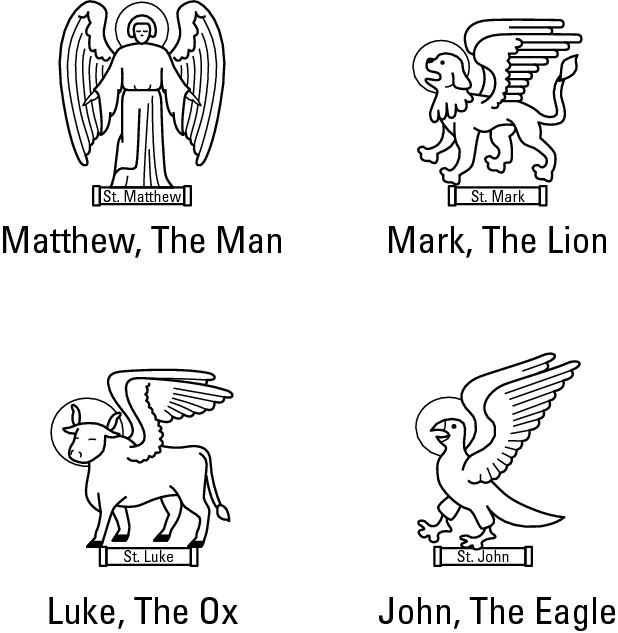

Figure 4-1: The writers of the four Gospels are often depicted like this from Revelation (Apoca- lypse) 4:7.

Chapter 4

Believing in Jesus

In This Chapter

Understanding the human nature and the divine nature of Jesus

Understanding the human nature and the divine nature of Jesus

Examining the Gospels from the Catholic perspective

Examining the Gospels from the Catholic perspective

Looking at some nasty rumors about Jesus that ran wild

Looking at some nasty rumors about Jesus that ran wild

Like all Christians, Catholics share the core belief that Jesus of Nazareth is Lord and Savior. The term Lord is used because Christians believe Jesus is divine — the Son of God. The term Savior is used because Christians believe that Jesus saved all humankind by dying for our sins.

Some people may think that Catholicism considers Jesus a hybrid — half human and half divine. That’s not the case at all. Catholicism doesn’t see Jesus as having a split personality or as a spiritual Frankenstein, partly human and partly divine. He’s regarded as fully human and fully divine — true man and true God. He’s considered one divine person with two equal natures, human and divine. This premise is the cornerstone of all Christian mysteries. It can’t be explained completely but must be believed on faith. (See Chapter 2 for the scoop on what faith really means.)

The Nicene Creed, a highly theological profession of faith, says volumes about what Christianity in general (and the Catholic Church in particular) believes about the person called Jesus. (You can read the Nicene Creed in Chapter 10 and the Apostles’ Creed in Chapter 2.) This chapter doesn’t say volumes, but it does tell you the need-to-know points for understanding Catholicism’s perspective on Jesus.

Understanding Jesus, the God-Man

Jesus, the God-Man, having a fully divine nature and a fully human nature in one divine person, is the core and center of Christian belief.

“True God” and “became man” are key phrases in the Nicene Creed, which highlights the fundamental doctrine of Jesus as the God-Man:

As God, Jesus possessed a fully divine nature, so He was able to perform miracles, such as changing water into wine; curing sickness, disease, and disability; and raising the dead. His greatest act of divinity was to rise from the dead Himself.

As God, Jesus possessed a fully divine nature, so He was able to perform miracles, such as changing water into wine; curing sickness, disease, and disability; and raising the dead. His greatest act of divinity was to rise from the dead Himself.

As man, Jesus had a human mother, Mary, who gave birth to Him and nursed Him. He lived and grew up like any other man. He taught, preached, suffered, and died. So Jesus had a fully human nature as well.

As man, Jesus had a human mother, Mary, who gave birth to Him and nursed Him. He lived and grew up like any other man. He taught, preached, suffered, and died. So Jesus had a fully human nature as well.

You can read the complete Nicene Creed in Chapter 10.

The human nature of Jesus

Jesus had a physical body with all the usual parts: two eyes, two ears, two legs, a heart, a brain, a stomach, and so on. He also possessed a human intellect (mind) and will (heart) and experienced human emotions, such as joy and sorrow. The Gospel According to John, for example, says that Jesus cried at the death of his friend Lazarus. Jesus wasn’t born with the ability to speak. He had to learn how to walk and talk — how to be, act, and think as a human. These things are called acquired knowledge. Other things were directly revealed to His human mind by the divine intellect; these are called infused knowledge.

Jesus did not share sin with human beings. As a Divine Person, He could not sin because it would mean negating Himself (sin is going against the will of God). Being human doesn’t mean being capable of sinning, nor does it mean that you’ve sinned somewhere along the line. Being human means having a free will and rational intellect joined to a physical body. Humans can choose to do good or choose to do evil.

Catholics believe that human beings don’t determine what’s good or evil because that’s intrinsic to the thing itself. Whether something is good or evil is independent of personal opinion. Murder is evil in and of itself. Someone may personally think an action is okay, but if it’s intrinsically evil, that person is only fooling himself and will eventually regret it. Jesus in His humanity always chose to do good, but that didn’t make Him any less human. Even though He never got drunk, swore, or told a dirty joke, He was still human.

Did Jesus have a wife and kids?

The last verse of the Gospel According to John (21:25) says, “There are also many other things which Jesus did; were every one of them to be written, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written.” The Bible is silent in some areas. Was Jesus ever married? Did He have a wife and children? The Bible doesn’t say either way. You could presume He was unmarried, because a wife is never mentioned. (The Bible does mention Peter’s mother-in-law being cured, but the Bible never classifies the other disciples and apostles as married or single.)

No Christian denomination or religion has ever believed that Jesus was married, even though the Bible never categorically states that He remained unmarried. The reason? Tradition. Christianity has maintained the tradition that Jesus was celibate and never married, even though the Bible at best implies it by never mentioning a wife or children.

Medieval literature is filled with stories on the Holy Grail, which was the alleged chalice Jesus used at the Last Supper. Folklore and legend imply that the Knights Templar may have found it while on Crusade, but there has never been any evidence whatsoever to establish or even suggest that the Grail symbolizes a bloodline running through European monarchies going back to the supposed offspring of Christ and Mary Magdalene. These stories are all fiction; there is no historical or biblical evidence to suggest otherwise.

Whenever the Bible is silent or ambiguous, Sacred Tradition fills in the gaps. So to Catholics, a written record in the Bible is that He was a man, His name was Jesus, and His mother was Mary, and a revealed truth of Sacred Tradition is that He never married.

Did Jesus have any brothers or sisters?

Some Christians believe Mary had other children after she had Jesus, but the Catholic Church officially teaches that Mary always remained a virgin — before, during, and after the birth of Jesus. She had one son, and that son was Jesus.

Another belief among some Christians is that Joseph had children from a prior marriage, and after he became a widower and married the mother of Jesus, those children became stepbrothers and stepsisters of Jesus. Those who believe that Jesus had siblings invoke Mark 6:3: “Is not this the carpenter, the son of Mary and brother of James and Joses and Judas and Simon and are not his sisters here with us?” And Matthew 12:46 says, “His mother and his brothers stood outside.”

So who were these brothers and sisters mentioned in the Gospel, if they weren’t actual siblings of Jesus? The Catholic Church reminds its members that the original four Gospels were written in the Greek language, not English. The Greek word used in all three occasions is adelphoi (plural of adelphos), which can be translated as brothers. But that same Greek word can also mean cousins or relatives, as in an uncle or a nephew.

An example is shown in the Old Testament. Genesis 11:27 says that Abram and Haran were brothers, sons of Terah. Lot was the son of Haran and thus the nephew of Abram, who was later called Abraham by God. Ironically, Genesis 14:14 and 14:16 in the King James Version of the Bible refer to Lot as the brother of Abraham. The Greek word used in the Septuagint version of the Old Testament, the version used at the time of Jesus, is again adelphos. Obviously, a word that denoted a nephew-uncle relationship was unavailable in ancient Hebrew or Greek. So an alternative use of brother (adelphos in Greek) is used in those passages, because Lot was actually Abraham’s nephew.

The Catholic Church reasons that if the Bible uses brother to refer to a nephew in one instance, then why not another? Why can’t the adelphoi (brothers) of Jesus be his relatives — cousins or other family members? Why must that word be used in a restrictive way in the Gospel when it’s used broadly in the Old Testament?

The Church uses other reasoning as well. If these brothers were siblings, where were they during the Crucifixion and death of their brother? Mary and a few other women were there, but the only man mentioned in the Gospel at the event was the Apostle John, and he was in no way related to Jesus, by blood or marriage. And before Jesus died on the cross, He told John, “Behold your mother” (John 19:27). Why entrust His mother to John if other adult children could’ve taken care of her? Only if Mary were alone would Jesus worry about her enough to say what He did to John.

And the Church asks this: If Jesus had blood brothers, or even half-brothers or stepbrothers, why didn’t they assume roles of leadership after His death? Why allow Peter and the other apostles to run the Church and make decisions if immediate family members were around? Yet if the only living relatives were distant cousins, nieces, nephews, and such, it all makes sense.

The debate will continue for centuries to come. The bottom line is the authoritative decision of the Church. Catholicism doesn’t place the Church above Scripture but sees her as the one and only authentic guardian and interpreter of the written word and the unwritten or spoken word, or Sacred Tradition.

The divine nature of Jesus

Catholics believe that Jesus performed miracles, such as walking on water; expelling demons; rising from the dead himself and raising the dead, such as Lazarus in Chapter 11 of the Gospel According to St. John; and saving all humankind, becoming the Redeemer, Savior, and Messiah. He founded the Catholic Church and instituted, explicitly or implicitly, all seven sacraments. (The seven sacraments are Catholic rituals marking seven stages of spiritual development. See Chapters 8 and 9 for more on the seven sacraments.)

Jesus is the second person of the Holy Trinity — God the Son. And God the Son (Jesus) is as much God as God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

The divine mind of Jesus was infinite, because He had the mind of God; the human mind of Jesus was, like the human mind, limited. The human mind could only know so much and only what God the Father wanted it to know. When asked about the time and date of the end of the world, Jesus’s apparent ignorance in Mark 13:32 “of that day or that hour, no one knows, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father,” is proof that the human intellect of Christ was not privy to all that the divine intellect of Christ knew.

To the Catholic Church, overemphasizing Jesus’s humanity to the exclusion of His divinity is as bad as ignoring or downplaying His humanity to exalt His divinity. To understand the Catholic Church’s stance on Jesus’s divinity even better, check out the doctrine of the Hypostatic Union in the section “Monophystism.”

The Savior of our sins; the Redeemer of the world

The study of Christ evokes two key questions. The first is “Who is Jesus Christ?” So far in this chapter, we’ve been addressing this question like this: Jesus is the son of God, and He is both God and man, divine and human. The second question is “Why did Jesus become man?” This question is answered by the Cross.

Catholics firmly believe that Jesus is the Savior of the world and the Redeemer of the human race. Jesus died for our sins and ransomed us from sin and death. As we explain in Chapter 3, the first (original) sin of Adam and Eve incurred guilt and punishment on all human beings. Their act of disobedience resulted in a serious wound to human nature. Because of original sin, humans lost God’s sanctifying grace; were expelled from paradise; and faced lives full of sickness and death, toil and labor. No one could enter heaven until a Savior was born.

Messiah is the Hebrew word for Savior, and in Greek the word is Christos. Both words also mean “Anointed One.” The Old Testament prophesied that a Savior would be sent to save the human race from sin and death, and Christians believe that God sent His son, Jesus, to be that Savior.

The Catholic Church graphically reminds her members of the human nature of Jesus by conspicuously placing a crucifix in every church. A crucifix is a cross with the crucified figure of Jesus attached to it. It’s a reminder to Catholics that Jesus didn’t pretend to be human. The nails in His hands and feet, the crown of thorns on His head, and the wound in His side where a soldier thrust a lance into His heart all poignantly remind the faithful that Jesus’s suffering, which is known as his Passion, was real. He felt real pain, and He really died. He was really human. If He had been only a god pretending to be human, His pain and death would have been faked.

In addition to reminding believers of Jesus’s human nature and His painful sacrifice, the crucifix reminds them that Jesus commanded us to take up our cross daily and follow Him. (For this reason, many Catholics have a crucifix at home.) The concept of dying to self is something spiritual writers speak of often. The process of dying to self involves enduring unavoidable suffering with dignity and faith. Seeing Jesus depicted on His cross is meant to encourage the devout to do likewise and offer up their sufferings as did Jesus.

The obedient Son of God

Catholicism regards Jesus as the eternal Son of the Father and teaches that the relationship between Father and Son is one of profound love. To understand this dynamic even better, see the nearby sidebar “Deep thoughts about Father and Son.”

Obedience is a sign of love and respect, and Catholics believe that Jesus obeyed the will of the Father. To Catholics, “Thy will be done” is more than just a phrase of the Our Father. It’s the motto of Jesus Christ, Son of God.

And Catholic belief maintains that God the Father’s will was for Jesus to

Reveal God as a community of three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) united in divine love

Reveal God as a community of three persons (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) united in divine love

Show God’s love for all humankind

Show God’s love for all humankind

Be humankind’s Redeemer and Savior

Be humankind’s Redeemer and Savior

The Gospel Truth: Examining Four Written Records of Jesus

The New Testament contains four Gospels, books of the Bible that tell the life and words of Jesus. The four evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, each wrote one of the four Gospels, considered by Christians to be the most important of all biblical text, because these four books contain the words and deeds of Jesus when He walked this earth.

Even though a different man wrote each of the four Gospels, the same Holy Spirit inspired each man. Inspiration is a special gift of the Holy Spirit given to the sacred authors (those who wrote the Bible) so that only the words that God wanted written down were written down.

Catholic beliefs about the Gospel

The Catholic Church emphasizes that it’s imperative to consider the four Gospels as actually forming one whole unit. The four Gospels aren’t four separate Gospels but four versions of one Gospel. That’s why each one is called The Gospel According to Matthew or The Gospel According to Mark, for example, and not Matthew’s Gospel or Mark’s Gospel. No one single account gives the entire picture, but like facets on a diamond, all sides form to make one beautiful reality. The faithful need all four versions to appreciate the full depth and impact of Jesus.

Both the Holy Spirit and the author, inspired by the Holy Spirit, intended to use or not use the same words and to present or not present the same ideas and images based on the particular author’s distinct audience. For more on how the Gospels are both inspired and audience-savvy, see the section “Comparing Gospels.”

Figure 4-1 shows how Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John are often depicted in art from Revelation (Apocalypse) 4:7. According to St. Ambrose (339-397), a Father of the Church (learned scholar), a man with wings symbolizes Matthew because he begins his Gospel account with the human origins and birth of Christ. Mark starts his account with the regal power of Christ, the reign of God, and is therefore symbolized by a lion with wings, which was held in high esteem by the Romans. Luke begins his account with the father of John the Baptist, Zachary, the priest, and is symbolized by an ox with wings because the priests of the temple often sacrificed oxen on the altar. John is shown as an eagle because he soars to heaven in his introduction to the Gospel with the preexistence of Christ as the Word (logos in Greek).

How the Gospels came to be

Were Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John standing on the sidelines taking notes as Jesus preached or performed miracles? No. In fact, only two of the four, Matthew and John, were actual apostles and eyewitnesses, so you can’t think of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John as, say, reporters covering a story for the media.

Before the Gospels were written, the words and deeds of Jesus were told by word of mouth. In other words, the Gospels were preached before they were written. The spoken word preceded the written word. And after it was written, because the papyrus on which the scrolls were written was so fragile, expensive, and rare, most people didn’t read the Word but heard it as it was spoken in church during Mass. The Church calls it the three-level development of the Gospel: first, the actual sayings and teachings of Christ; second, the oral tradition where the apostles preached to the people what they saw and heard; and third, the writing by the sacred authors to ensure that the message wouldn’t be altered.

Comparing Gospels

The Catholic Church regards the entire Bible as the inspired and inerrant (error-free) Word of God, so the Gospels in particular are crucial because they accurately relate what Jesus said and did while on earth. As we discuss in Chapter 2, the Catholic Church believes that the Bible is sacred literature, but as literature, some parts of it should be interpreted literally, and other parts are intended to be read figuratively. The Gospels are among the books that are primarily interpreted literally insofar as what Jesus said and did.

Matthew and Luke

Matthew opens his Gospel with a long genealogy of Jesus, beginning with Abraham and tracing it all the way down to Joseph, the husband of Mary, “of whom Jesus was born, who is called the Messiah.”

Matthew was addressing potential converts from Judaism. A Jewish audience was probably interested in hearing this family tree because the Hebrew people are often called the Children of Abraham. That’s why Matthew began with Abraham and connected him to Jesus to open his Gospel.

Luke offers a similar genealogy to Matthew’s, but he works backward from Jesus to Adam, 20 generations before Abraham. Luke was a Gentile physician, and his audience was Gentile, not Jewish. Neither Matthew nor Luke used editorial fiction, but each carefully selected what to say to his respective audience through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. A Gentile audience wasn’t as concerned with a connection to Abraham as a Jewish audience. Gentiles were interested in a connection between Jesus and the first man, Adam, because Gentiles were big into Greek philosophy. Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle — just to mention a few famous Greek thinkers who lived before Christ — philosophized about the origins of humanity and, thus, making a link between Jesus and the first man would have greatly appealed to them. In the Sermon on the Mount, Matthew mentions that prior to giving the sermon, Jesus “went up on the mountain” (Matthew 5:1), but Luke describes Jesus giving a Sermon on the Plain, “a level place” (Luke 6:17). Both men quote the teachings from these sermons, called the Beatitudes. See the following version from Matthew 5:

Seeing the crowds, he went up on the mountain, and when he sat down his disciples came to him. And he opened his mouth and taught them, saying:

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted.

“Blessed are the meek, for they shall inherit the earth.

“Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied.

“Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy.

“Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God.

“Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called sons of God.

“Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.

“Blessed are you when men revile you and persecute you and utter all kinds of evil against you falsely on my account. Rejoice and be glad, for your reward is great in heaven, for so men persecuted the prophets who were before you.”

Now contrast the Sermon on the Mount in the Gospel of Matthew with Luke 6:17–26, which follows:

And he came down with them and stood on a level place, with a great crowd of his disciples and a great multitude of people from all Judea and Jerusalem and the seacoast of Tyre and Sidon, who came to hear him and to be healed of their diseases; and those who were troubled with unclean spirits were cured. And all the crowd sought to touch him, for power came forth from him and healed them all. And he lifted up his eyes on his disciples, and said:

“Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.

“Blessed are you that hunger now, for you shall be satisfied.

“Blessed are you that weep now, for you shall laugh.

“Blessed are you when men hate you, and when they exclude you and revile you, and cast out your name as evil, on account of the Son of man! Rejoice in that day, and leap for joy, for behold, your reward is great in heaven; for so their fathers did to the prophets.

“But woe to you that are rich, for you have received your consolation.

“Woe to you that are well fed now, for you shall hunger.

“Woe to you that laugh now, for you shall mourn and weep.

“Woe to you when all men speak well of you, for so their fathers did to the false prophets.”

So why the difference in location for these sermons — mount and plain?

Matthew mentions the occasion of the Sermon on the Mount because his Jewish audience would have been keen on such a detail. The reason? Moses was given the Law, the Ten Commandments, on Mount Sinai. So Jesus was giving the law of blessedness, also known as the Beatitudes, also from a mount. Matthew also makes sure to quote Jesus, saying that He had “come not to abolish them [the law and the prophets], but to fulfill them,” (Matthew 5:17) also appealing to a Jewish listener. Moses gave the Ten Commandments that came from God to the Hebrew people, and now Jesus was going to fulfill that Law.

Luke, on the other hand, mentions the time that the sermon was given on a plain. Why mention the obscure detail of a level ground? Luke was writing for a Gentile audience. Unlike the Jewish audience of Matthew, which was used to the Law being given from God to Moses on Mount Sinai, the Gentiles were accustomed to giving and listening to philosophical debates in the Greek tradition. Philosophers such as Plato, Socrates, and Aristotle debated one another on level ground, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, eye-to-eye, instead of lecturing from an elevated podium, in order to give a sense of fairness and equality to the discussion. Because a Gentile audience would have been more interested in a speech given by Jesus in similar fashion, Luke retold such an occurrence.

A slight difference can be detected in some of the wording of Luke’s account versus that of Matthew, as well as an addition of “woe to you” given by Jesus to correspond with each “blessed are you,” which isn’t found in Matthew. Again, a preacher often adapts an older sermon by adding to, subtracting from, or modifying his original work, depending on his second audience. The Catholic Church maintains that the discrepancy comes from a change Jesus made because neither sacred author would feel free to alter anything Jesus said or did on his own human authority.

Mark

Mark is the shortest of the four Gospels, due to the fact that his audience was mainly Roman. When you belong to an imperial police state, you’re not as concerned about making intricate connections to a Hebrew past, and you’re not interested in lengthy philosophical dialogues. You want action. That’s why the Gospel According to Mark has fewer sermons and more movement. It’s fast-paced, nonstop, continuous narrative, like an excited person telling the events “a mile a minute.” Romans would have been far more attentive to the Gospel According to Mark than to the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, or John.

Mark explicitly describes the Roman Centurion, a military commander of a hundred soldiers, at the Crucifixion as making the proclamation, “Truly, this man was the Son of God” (Mark 15:39). His Roman audience would’ve certainly perked up when that was said because it was an act of faith from one of their own kind.

Like Luke, Mark wasn’t one of the original 12 apostles. Matthew and John were apostles, but Luke and Mark were 2 of the 72 disciples. The apostles were there in person to witness all that Jesus said and did. The disciples often had to resort to secondhand information, told to them by other sources. Luke most likely received much of his information from Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Mark undoubtedly used his friend Peter, the chief apostle, as his source.

John

John was the last one to write a Gospel, and his is the most theological of the four. The other three are so similar in content, style, and sequence that they’re often called the Synoptic Gospels, from the Greek word sunoptikos, meaning summary or general view.

John, who wrote his Gospel much later than the others, was writing for a Christian audience. He presumed that people had already heard the basic facts, and he provided advanced information to complement the Jesus 101 material covered in Matthew, Mark, and Luke. In other words, The Gospel According to John is like college calculus, whereas the Synoptic Gospels are like advanced high-school algebra.

John sets the tone by opening his Gospel with a philosophical concept of preexistence: Before Jesus became man by being conceived and born of the Virgin Mary, He existed from all eternity in His divinity because He’s the second person of the Holy Trinity. Take a look at the first line from the Gospel According to John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God.”

This is a very philosophical and theological concept. John wanted his audience to see Jesus as being the living Word of God: As he says, “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). He was saying that Jesus was the incarnate Word — the Word taking on flesh. The first book of the Bible, Genesis, starts with the same phrase John uses in the opening of his Gospel: “In the beginning.” According to Genesis 1:3, God said, “Let there be light; and there was light.” In other words, by merely speaking the word, God created. John built on that in his Gospel, saying that Jesus was the Word. The Word of God wasn’t a thing but a person. The Word was creative and powerful. Just as God said the word and light were created, Jesus spoke the word and the blind received their sight, the lame walked, and the dead came back to life.

Dealing with Heresy and Some Other $10 Words

Christians were violently and lethally persecuted for the first 300 years after the death of Jesus — from the time of Emperor Nero and the burning of Rome, which he blamed on the Christians. So for the first 300 years, Christianity remained underground. Through word of mouth, Christians learned about Jesus of Nazareth and his preaching, suffering, death, Resurrection, and Ascension.

It wasn’t until a.d. 313, when Roman Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity in his Edict of Milan, that Christians were even allowed to publicly admit their religious affiliation. But once Christianity became legal, it soon became predominant and even became the state religion.

Leaving the catacombs (underground cemeteries sometimes used by Christians to hide from the Romans and as places of worship during times of persecution) and entering the public arena, Christians began devoting themselves to theological questions that the Bible didn’t specifically address. For example, Scripture teaches that Jesus was God and man, human and divine. Yet how was He both? How were the human and divine natures of Jesus connected? So the second 300 years after Jesus’s death, the fourth to seventh centuries, became a Pandora’s box of theological debate.

To the Catholic Church, heresy is the denial of a revealed truth or the distortion of one so that others are deceived into believing a theological error. After Christianity was legalized, the Christological heresies that referred to the nature of Christ became rampant. Debates often degenerated into violent arguments, and the civil authorities, such as the Roman Emperor, often intervened, urging or even demanding that the religious leaders, such as the pope, patriarchs, and bishops, cease the unrest by settling the issues once and for all. This section explains some of the heresies, or false rumors, that plagued the Church during early Christianity.

Gnosticism and Docetism

Gnosticism comes from the Greek work gnosis, for knowledge. From the first century b.c. to the fifth century a.d., Gnostics believed in secret knowledge, whereas the Judeo-Christians were free and public about disclosing the truth divinely revealed by God. Gnostics believed that the material world was evil and the only way to salvation was through discovering the “secrets” of the universe. This belief flew in the face of Judaism and Christianity, both of which believed that God created the world (Genesis) and that it was good, not evil. Keeping revelation secret wasn’t meant to be; rather, it should be shared openly with others.

Docetism, a spin-off from Gnosticism, comes from the Greek word dokesis, meaning appearance. In the first and second centuries a.d., Docetists asserted that Jesus Christ only appeared to be human. They considered the material world, including the human body, so evil and corrupt that God, who is all good, couldn’t have assumed a real human body and human nature. He must have pretended.

The Gnostic antagonism between the spiritual and the material worlds led Docetists to deny that Jesus was true man. They had no problem with His divinity, only with believing in His real humanity. So if that part was an illusion, then the horrible and immense suffering and death of Jesus on the cross meant nothing. If His human nature was a parlor trick, then His Passion also was an illusion.

The core of Christianity, and of Catholic Christianity, is that Jesus died for the sins of all humankind. Only a real human nature can feel pain and actually die. Docetism and Gnosticism were considered hostile to authentic Christianity, or, more accurately, orthodox Christianity. (The word orthodox with a small letter o means correct or right believer. However, if you see the capital letter O, then Orthodox refers to the eastern Orthodox Churches, such as the Greek, Russian, and Serbian Orthodox Churches.)

Arianism

Arianism was the most dangerous and prolific of the heresies in the early Church. (By the way, the Arianism that we’re referring to isn’t about modern-day skinheads with swastikas and anti-Semitic prejudices.) Arianism comes from a cleric named Arius in the fourth century (a.d. 250–336), who denied the divinity of Jesus. Whereas Docetism denied his humanity, Arianism denied that Jesus had a truly divine nature equal to God the Father.

Arius proposed that Jesus was created and wasn’t of the same substance as God — He was considered higher than any man or angel because He possessed a similar substance, or essence, but He was never equal to God. His Son-ship was one of adoption. In Arianism, Jesus became the Son, whereas in orthodox Christianity, He was, is, and will always be the Son, with no beginning and no end. Arianism caught on like wildfire because it appealed to people’s knowledge that only one God existed. The argument was that if Jesus was also God, two gods existed instead of only one.

Emperor Constantine, living in the Eastern Empire, was afraid that the religious discord would endanger the security of the realm. He saw how animate and aggressive the argument became and ordered that a council of all the bishops, the patriarchs, and the pope’s representatives convene to settle the issue once and for all. The imperial city of Nicea was chosen to guarantee safety. In Nicea, the world’s bishops decided to compose a creed that every believer was to learn and profess as being the substance of Christian faith. That same creed is now recited every Sunday and Holy Day at Catholic Masses all over the world. It’s known as the Nicene Creed, because it came from the Ecumenical Council of Nicea in a.d. 325.

The punch line that ended the Arianism controversy was the phrase “one in being with the Father” in the Nicene Creed (the phrase that has recently been replaced by “consubstantial with the Father”). The more accurate English translation of the Greek and Latin, however, is consubstantial or of the same substance as the Father. This line boldly defied the Arian proposition that Jesus was only similar but not equal in substance to the Father in terms of His divinity.

Nestorianism

Another heresy was Nestorianism, named after its founder, Nestorius (c. 386–451). This doctrine maintained that Christ had two hypostases (persons) — one divine and one human. Nestorius condemned the use of the word Theotokos, which was Greek for bearer or mother of God. If Jesus had two persons, the most that could be said of Mary was that she gave birth to the human person of Jesus and not to the divine. Nestorius preferred the use of the word Christotokos or Christ-bearer to Theotokos.

Another Ecumenical Council was convened, this time in the town of Ephesus in a.d. 431, where the participants ironed out the doctrine that Jesus had one person, not two, but that two natures were present — one human and one divine. Because Christ was only one person, Mary could rightly be called the Mother of God because she gave birth to only one person.

In other words, Jesus didn’t come in parts on Christmas Day for Mary and Joseph to put together. He was born whole and intact, one person, two natures. The Church says that because Mary gave birth to Jesus, the Church could use the title Mother of God (Theotokos), realizing that she didn’t give Jesus His divinity. (This concept is similar to the belief that your mother gave you a human body, but only God created your immortal soul. Still, you call her mother.)

Monophysitism

The last significant heresy about Jesus was known as Monophysitism. This idea centered on a notion that the human nature of Jesus was absorbed into the divine nature. Say, for example, that a drop of oil represents the humanity of Jesus and the ocean represents the divinity of Jesus. If you put the drop of oil into the vast waters of the ocean, the drop of oil, representing His humanity, would literally be overwhelmed and absorbed by the enormous waters of the ocean — His divinity.

The Ecumenical Council of Chalcedon in a.d. 451 condemned Monophyistism. A simple teaching was formulated that one divine person with two distinct, full, and true natures, one human and one divine, existed in Jesus. These two natures were hypostatically (from the Greek hypostasis, for person) united into one divine person. Thus the Hypostatic Union, the name of the doctrine, explained these things about Jesus:

In His human nature, Jesus had a human mind just like you. It had to learn like yours. Therefore, the baby Jesus in the stable at Bethlehem didn’t speak to the shepherds on Christmas Eve. He had to be taught how to speak, walk, and so on. Likewise, His human will, like yours, was free, so He had to freely choose to embrace the will of God.

In His human nature, Jesus had a human mind just like you. It had to learn like yours. Therefore, the baby Jesus in the stable at Bethlehem didn’t speak to the shepherds on Christmas Eve. He had to be taught how to speak, walk, and so on. Likewise, His human will, like yours, was free, so He had to freely choose to embrace the will of God.

In other words, in His humanity, Jesus knew what He learned. And He had to freely choose to conform His human will to the divine will. (Sin is when your will is opposed to the will of God.) Any human knowledge not gained by regular learning was infused into His human intellect by His divine intellect. Jesus knew that fire is hot just as you’ve learned this fact. He also knew what only God could know, because He was a divine person with a human and a divine nature. The human mind of Christ is limited, but the divine is infinite. His divinity revealed some divine truths to His human intellect, so He would know who He is, who His Father is, and why He came to earth.

The divine nature of Jesus had the same (not similar) divine intellect and will as that of God the Father and God the Holy Spirit. As God, He knew and willed the same things that the other two persons of the Trinity knew and willed. Thus, in His divinity, Jesus knew everything, and what He willed, happened.

The divine nature of Jesus had the same (not similar) divine intellect and will as that of God the Father and God the Holy Spirit. As God, He knew and willed the same things that the other two persons of the Trinity knew and willed. Thus, in His divinity, Jesus knew everything, and what He willed, happened.

As both God and man, Jesus could bridge the gap between humanity and divinity. He could actually save humankind by becoming one of us, and yet, because He never lost His divinity, His death had eternal and infinite merit and value. If He were only a man, His death would have no supernatural effect. His death, because it was united to His divine personhood, actually atoned for sin and caused redemption to take place.

As both God and man, Jesus could bridge the gap between humanity and divinity. He could actually save humankind by becoming one of us, and yet, because He never lost His divinity, His death had eternal and infinite merit and value. If He were only a man, His death would have no supernatural effect. His death, because it was united to His divine personhood, actually atoned for sin and caused redemption to take place.

It’s a mouthful to be sure, but the bottom line in Catholic theology is that the faithful fully and solemnly believe that Jesus was one divine person with a fully human nature and a fully divine nature. Each nature had its own intellect and will. So the divine nature of Jesus had a divine intellect and will, and the human nature of Jesus had a human intellect and will.

It’s important to keep in mind that Catholicism doesn’t depend

It’s important to keep in mind that Catholicism doesn’t depend  Despite what you may read in some modern novels, Jesus and Mary Magdalene were never a couple, legally or romantically. Counterfeit Gospels were written a few hundred years after the legitimate ones that alleged such a relationship with the intent to undermine the Church. No one ever took them seriously, and no accredited scholar today gives them any credibility.

Despite what you may read in some modern novels, Jesus and Mary Magdalene were never a couple, legally or romantically. Counterfeit Gospels were written a few hundred years after the legitimate ones that alleged such a relationship with the intent to undermine the Church. No one ever took them seriously, and no accredited scholar today gives them any credibility. Although Christians, Jews, and Muslims all believe in one God, Christians believe in a

Although Christians, Jews, and Muslims all believe in one God, Christians believe in a  If you look closely at a crucifix, you may see the letters INRI on it. Those letters are an abbreviation for the Latin words

If you look closely at a crucifix, you may see the letters INRI on it. Those letters are an abbreviation for the Latin words