The condor known as AC-9 or Igor watched trapper Pete Bloom catch several of the last wild condors from the top of a nearby tree. Igor himself was trapped on Easter Sunday, 1987. (Photo by Dave Clendenen; courtesy of Peter Bloom)

In 1986 and 1987, the last free-flying California condors were trapped by biologists like Peter Bloom (pictured) of the National Audubon Society and Dave Clendenen of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Peter Bloom)

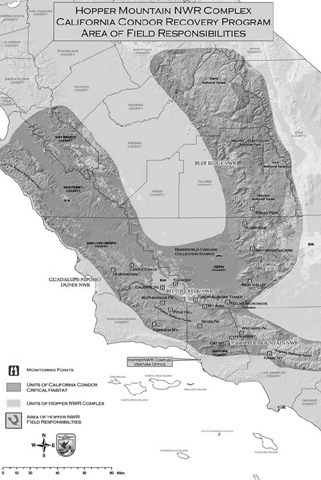

After World War II, the range of the condor followed this wishbone-shaped set of mountains. (Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

When creatures like the saber-toothed cat and the mastodon were alive, the California condor ranged across large parts of North America. (Knight Mural of Pleistocene Life, Rancho La Brea Tar Pits #4948 courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History)

Indian tribes in California revered the birds and left paintings of condors on rocks. (Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

“I believed this to be the largest bird in North America,” wrote Lewis in his journal in 1806; Clark wrote the same thing and added a rough sketch of the bird’s head. (Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society)

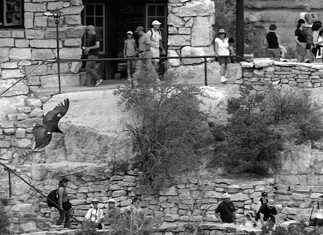

Hundreds of years after Lewis and Clark explored the Columbia River, condors were returned to the Vermillion cliffs and the Grand Canyon. (Christie Van Cleve)

In 1840, John James Audubon immortalized the “California Vulture” in “The Birds of America.” (Courtesy of Haley and Steele)

By the early 1900s, hunters and egg collectors had all but wiped the species out. (Photo by R. Corado; courtesy of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology)

Joseph P. Grinnell, a legendary naturalist, was among the first to describe the bird as a “symbol of our lessening wilderness.” (Courtesy of the Bankroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

In 1939, Carl Koford was the first to study the behavior of wild condors and urged hunters, loggers, hikers, photographers, and scientists to stay away from the species. (Courtesy of Rolf R. Koford)

At times, Koford and some of his friends handled condors in their nest caves. Koford later denounced the “hands-on” approach as a threat to the future of the species (Ed Harrison, above). (Photo by Carl Koford; courtesy of Lloyd Kiff)

In the desperate 1980s, when ravens were seen breaking condor eggs and eating the contents, biologists like Rob Ramey shot at birds that approached the nest caves. (Courtesy of Rob Roy Ramey II)

,/p>

,/p>

By the 1980s, almost all of the remaining wild condors had been trapped at least once, and most had numbered ID tags and radio transmitters hanging from the front of their wings. (Christie Van Cleve)

In 1987, the last wild condor was captured and taken to the San Diego Wild Animal Park. (Courtesy of the Zoological Society of San Diego)

Captive birds began producing one egg every year, and some laid two or even three. (Courtesy of the Zoological Society of San Diego)

Some of the condor chicks were raised by biologists wearing condor puppets on their hands. (Courtesy of the Zoological Society of San Diego)

Even the notoriously antisocial condor known as Topa Topa fathered an egg. (Anthony Prieto)

Residents of southern Utah and northern Arizona said they didn't want the condor around. (Christie Van Cleve)

In 1996 the birds were released near the Grand Canyon, where they sometimes buzzed the crowds on the South Rim.

Condors often soar for hundreds of miles in a single day. (Photo by Christie Van Cleve)

Some birds raised in zoos have had trouble learning to be wild, turning up at Burger Barns, airport runways, and on the decks of homes built on the sides of mountains. (Photo by Denise Stockton; courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Condors are threatened by lead fragments found in the carcasses abandoned by hunters—and by the nuts and bottle caps that sometimes show up when the birds are X-rayed. (Photo courtesy of the Los Angeles Zoo)

In the Hopper Mountain Condor Refuge in California, birds are regularly trapped and tested for lead. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

Condors that fail to adjust to the wild are flown to the zoos for treatment. Most are eventually returned to the wild. (Photo courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

The condor that was known as AC-9 or Igor was returned to the wild in the fall of 2001 with a new set of numbers on its wings. Condor biologists who track his movements say he seems to be thriving. (Anthony Prieto)

The matriarch, also known as AC-8, free in better days. (Anthony Prieto)

Last year, after having a tumor removed and surviving a severe case of lead poisoning, the matriarch was shot dead by a pig hunter who said he didn't know what condors were. (Courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)