OBJECTIVE CRESCENT LAKE

CHAPTER TEN

TIPTOE THROUGH THE DEADLY TULIPS

Mosul Part Three, Iraq, 2008

At the end of 2007 a few of us, including me and Jason, submitted our promotion packets for sergeant first class (E-7). All were accepted – Jason moved to Alpha Company later and I to battalion staff. This would be my last deployment to Mosul as a staff sergeant (E-6), age 27, squad leader of 3rd Squad, 3rd Platoon, Charlie Company.

Our platoon had been in Mosul more than any of the others and we joked that we should buy a summer home there. We did not even need a map to drive through the city since we had it memorized by now. Frankly, this was awesome on our part because in the event that the navigation system failed we were still operable and we could give route directions over the radios. This deployment pushed us to our limit mentally as well as physically. Between our two platoons we conducted over 160 combat missions within our 90-day deployment cycle.

During our first few weeks my squad was tasked out to support Army Special Forces. They had a small troop deployed and we drove their vehicles and navigated the city on the way to their targets. Our squad had dropped from an all-time high of 13 to about nine or ten. I broke off four senior Rangers to accompany me on this tasking, and we were sad to leave our platoon behind since they were going to have a lot of fun. After all, who wants to chauffeur other units and never get off the truck? We did get to do a few helicopter operations with them, which was fun, but blocking positions on most of the missions were always boring. But Army Special Forces was small and needed some additional muscle.

About a month later we rotated with another set of Rangers from 2nd Platoon. Within the first week of that rotation, they got into a gunfight and suffered one Ranger KIA. Specialist Thomas F. Duncan III, age 21, died of gunshot wounds suffered during combat operations in Sinjar, Iraq, on June 9, 2008. They had taken a helicopter flight out west of the city to a typical small village. They were sucked in and baited into a gunfight from barricaded shooters along a half-crumbled wall. The fight ended with a tragic blue-on-blue KIA. What had happened, it seemed, was that once the gunfight began, the Ranger blocking position shifted its location to put accurate fire onto the target location but somehow this was not properly understood or communicated. Through either miscommunication or misinterpretation during the fight an aircraft ended up strafing blue elements along with the enemy force. Such is the fog of war. It really sucked and put the guys into a funk early into their deployment. This happened alongside Army Special Forces and questions were asked about their operation. During the investigation a few things came to light but all one can say is human beings make mistakes and will always make mistakes. It reinforced that you always needed to make sure everyone knows where everyone is, especially if you are using a non-organic asset – be that a gunship or helicopters flying support. One way to do this is by calling and checking in with the platoon sergeant to confirm everyone involved in the mission. That is his job and it helps paint a complete picture for ground and air assets. Accountability of people is especially critical during combat operations.

We had day and night platoons to execute our tasking during this deployment. It was a lot of fun but it was also exhausting. We refined our craft more and more, mission by mission. The target refinement was better and, as a result, the targeting sequences were a lot smoother on the ground. I would say it was a tenfold improvement on what constituted a target. Our guys became very good at delivering intel using the ammo can distribution system dropped off to us by gunships in the middle of our missions. We conducted Stryker “ramp side planning” in the back of our vehicle platform and reviewed the imagery and intelligence provided. Jason, who was the convoy leader, worked out the route to be taken to the follow-on target. Planning took maybe 10–15 minutes. We drove, entered the compound, and cleared it within an hour. Another ammo can was dropped off, and onto the next target we went until there was no space in our vehicles for additional detainees. The continued succession of targets wore on the guys and we needed a break. Finally, thanks to some inclement weather, we got one. Oh, thank you break. A storm clouded the sky and our air assets were grounded. But we were back in action far too soon.

A typical raid in Iraq involved driving vehicles into the target area, where we dismounted and continued the mission on foot. We usually stopped about two to three blocks away from the target to stay out of vehicle noise range. We searched for the correct target compound and checked both sides of the block.

On one mission and about a block away from our objective there was an impromptu Iraqi police checkpoint. We were in the process to deconflict – basically letting everyone know who-was-where to avoid friendly fire when exactly that happened. The Iraqi police engaged one of our guys, Erich, who carried a ladder. At 5'10" and 200 pounds, Erich was a sniper team leader and one of the most knowledgeable snipers to work with. He went down. Mitch, Allen, and I had been waiting for the final deconfliction of the target area when this happened. Mitch was one of my great team leaders from 3rd Squad. He was quick thinking in a fight and an all-around solid Ranger. We took a few steps ahead of Erich and laid down a base of fire onto the police post. We were on the crest of a hill that led down to the police forces. Mitch grabbed Erich and moved him away and down the street. Allen and I fired downrange while the entire platoon ran to the sound of the guns. I was about a foot away from a cinder wall on one knee and Allen was above me. We poured on more lead. More and more guns showed up, machine guns, then Strykers, and we all shot at the Iraqi police. It was a gunfight back and forth, but as we believed them to be green forces we directed our fire away from them, instead hammering everything around them. We simply wanted them to stop firing at us. Our massive platoon leader, Walker, 6'2" and 220 pounds of him, was on the radio still trying to deconflict the area. But once the .50cal guns opened up the police finally stopped shooting and one of our interpreters used the bullhorn to shout at them that we were friendly forces. The fight ended and the whole action had lasted no more than five minutes. It was a bad night for Erich, who had been clipped on the outside of his knee. We completed the mission, conducted our actions on the objective, cleared, searched, and found nothing and then we took him to the hospital. But, as luck would have it, the bullet had missed every important thing in his knee, and he was released from the Combat Surgical Hospital (CSH) a few days later. Erich was more annoyed at having a bullet hole through his new pants than he was about his knee. Much to my amusement or annoyance, he kept griping about his pants. Ranger! Green on blue. Blue on blue. It happens. It’s war and it is unavoidable.

• • •

I served in Charlie Company from 2003 to 2008, and one particular gunfight inside a target building stands out to me as a testimony to our perfection of our craft and our silent entries. The tasking was named Objective Crescent Lake and it involved the interdiction of Abu Kalaf, the emir of al Qaeda in Mosul, who had been accidentally released from prison by the Iraqis in an attempt to purge the overcrowded detention facilities. Abu Ghraib was shut down because of detainee abuse and it was during the merging of detainees into one larger facility that he was allowed to leave.

Recapturing Kalaf was a personal issue for our battalion commander because he had been wounded during the gunfight to apprehend the emir the first time around. Our battalion commander was certain that the fugitive would return to Mosul. He knew Kalaf well, knew that his house was within the city, and so we used local national assets to run a recce down the street in front of his house to confirm or deny his presence. We didn’t want to burn the target and be forced to chase after him in a hostile environment. Our local assets conducted a route reconnaissance and confirmed Abu Kalaf was on target.

Our challenge was how to best approach the target compound without getting compromised. Kalaf had a good personal protection system set up so we knew we couldn’t simply drive up without being seen or heard. This was based on intel from our battalion commander who had captured him previously. We were certain we could drive HUMVEEs into the area but not the Stryker platform. I suggested that a dismounted patrol was the best approach to the target compound without the emir’s early warning system kicking in. We decided not to take any risks whatsoever on this particular mission. We agreed on a dismounted patrol and knew that it would take a lot longer to set all the pieces before taking down the building. The reason for the more cautious approach was simple: Abu Kalaf had only been out of jail for about seven to ten days and naturally would be skittish. We had intel that prior to his arrest he had had a personal security detail of two to three bodyguards with him all the time. We also knew, based on his previous capture, that he had a suicide bomber within his protection circle. We assumed that we had one to deal with now as well. We therefore planned on possibly being compromised and, if so, that there would be a firefight with his security personnel and a suicide bomber. Our commander was not too keen on a roughly 1.5km walk to the target within the war-ravaged city, especially since we were going after such a high-profile target. But our briefing was very detailed and our confidence was high that we would be able to set the pieces unseen. He believed in us and gave us the okay.

Our plan called for the assault force to drive up to a nearby Iraqi police station and then conduct the dismounted patrol. Recently we and other U.S. elements had been engaged by the police but had been ordered not to shoot back; instead, they had to wait until their headquarters was able to call the police to have them stop firing. To avoid a similar situation we drove our Strykers off the main supply route, across a bridge, and to the police station. After we deconflicted with them, we left our liaison officer and interpreter with the police to listen to radio comms alerting the police to possible crowd disturbances during the mission. It would be the police’s responsibility to deal with any potential mob.

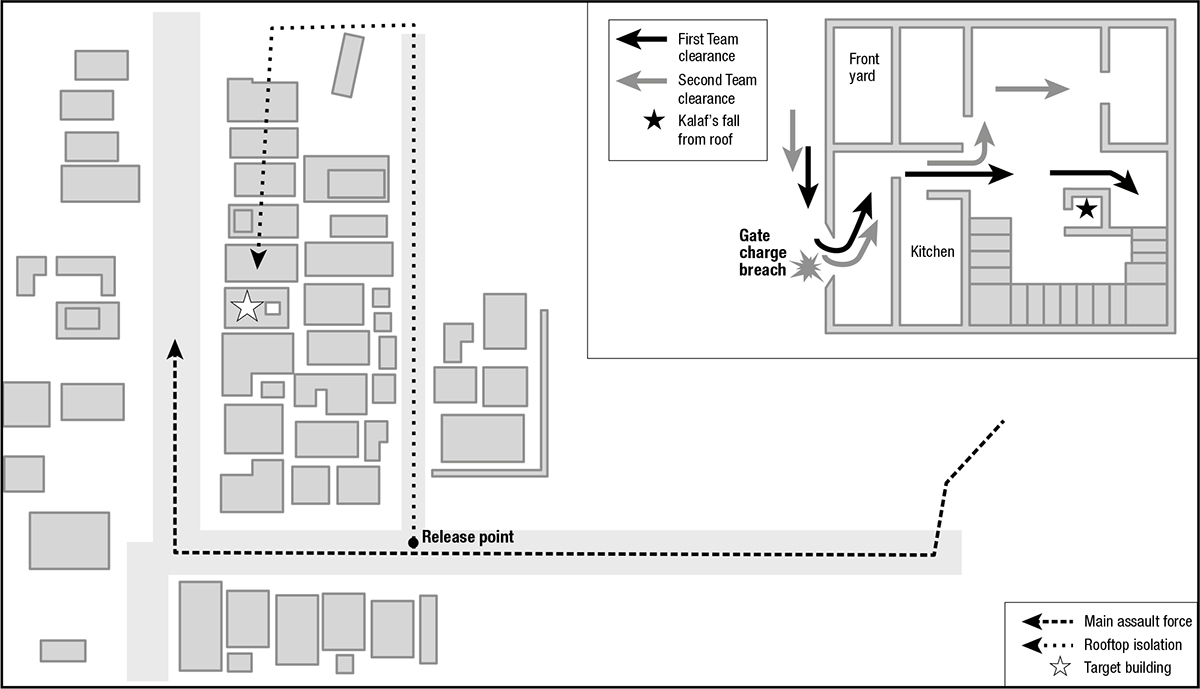

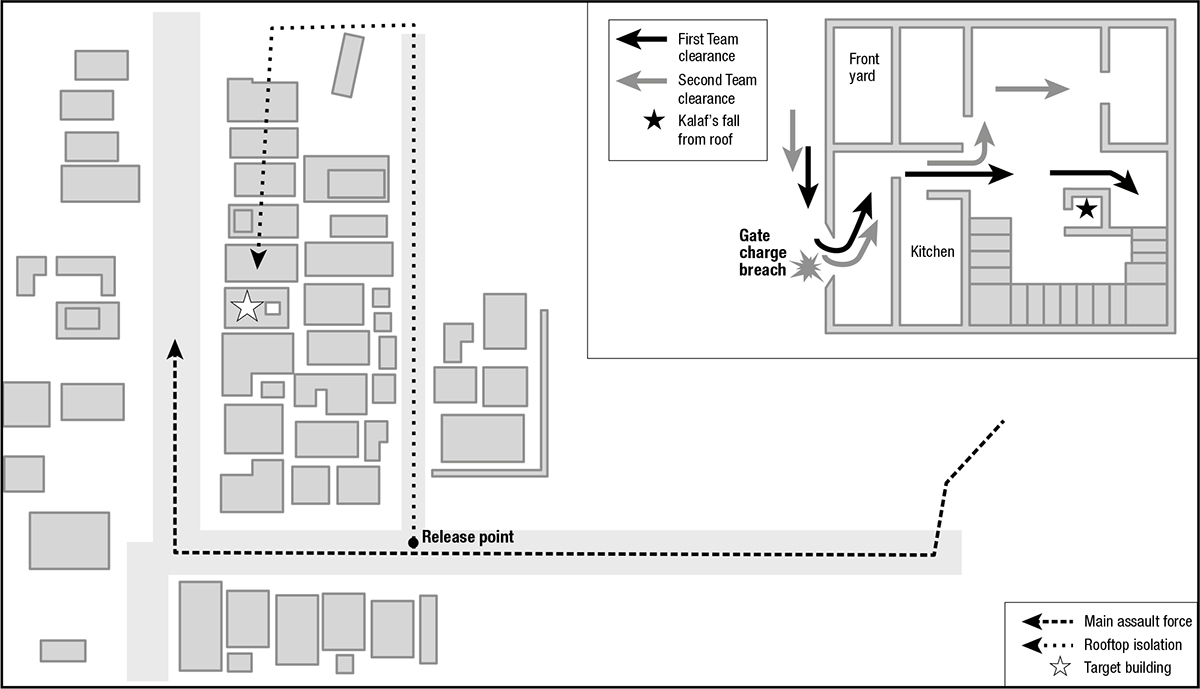

We continued a little bit farther down the road where we dismounted. The route we followed was along a main artery for a little over a klick. We made a sharp left, then a right, and, on our final approach to Objective Crescent Lake, we held up short and crossed a large drainage ditch running through the city using the typical one‑person-wide footbridge. Our assault element moved across, turned left, then right onto a road where we held back about a block away from the target compound. This was our release point. So far, our walk in had been perfectly uneventful; nobody had tripped or fallen, no metal had clinked. It was more or less a quiet night. We had alerted no one.

The target block was about five houses deep with around a dozen houses around. We set security on the west side of the block. The release point was one block away from the road we needed to turn right on. The target compound was smack in the middle of it. We released the isolation squad, including our sniper teams. They made a right turn from our main travel route and followed along the block’s near side, continued until the end of it, and then turned around – basically a U-shape movement. Five Rangers, composed of two snipers and a small security force, slowly and quietly hopped over the wall and climbed with assault ladders. People in the Middle East often sleep on the rooftops in the summers because their houses are too hot at night. During our planning process we felt there would be a high possibility of civilians up top so we had to be aware. If we encountered anyone, we would secure them by tying them up temporarily. In a 360-degree urban combat environment it was always nice to have guns up high, so they could deal with any and all threats. We knew that we would not be shot at from someone up top without a response from our sniper teams. Knowing that people were asleep basically meant our guys had to tiptoe around the sleeping bodies and then hop-scotch across various roofs to get to their location. They proceeded to cross rooftops on their way back toward us, halfway down the block, to their position near the target building.

Meanwhile, the other elements involved in the assault got antsy because the movement of the isolation teams was so slow. I thought, Holy crap, what are they doing? Drinking tea? A call came in asking if one element could move in closer to the next intersection so they could get eyes on the target building. The answer was, of course, a no. A few more minutes passed and the same question was asked, but with the add on that if something were to happen now they could offer no assistance or interdiction to the isolation team. Still the answer was no.

The rooftop team called in the building numbers as they made their way across them. That way we knew where they were at all times. Later I heard that while they hop-scotched across one rooftop an Iraqi woman woke up, sat up, and stared at Team Leader Mitch, a.k.a. Catfish, an Oklahoma boy from 2nd Squad. He calmly put his finger to his lips and whispered “shh.” She went back to sleep as though nothing had happened. Tiptoeing through the tulips.

At this point I felt that the isolation element was too far away to support them if something went down. So, this time I asked if we could move a team up to the target street “just in case.” The answer this time was yes. We moved forward another block and finally put eyes on target. Our briefing called for a shock and awe entry, not our favorite since we had perfected the silent entry technique, but we needed to surprise and disorient the enemy within the compound.

The rooftop team was in place and the assault force placed breaches on the gate. We gave out “set” calls that we were ready, and waited for all the blocking positions to report. We were on the left side facing the gate. As the set calls came back the command to execute was given. We blew the gate charge. My E-5 team leader from 3rd Squad, another Mitch, not Catfish from 2nd Squad, was the breacher for the gate. He also expected the front door to be locked so it needed to be breached almost simultaneously to the explosive breach of the gate. The gate blew and we “flowed” in and immediately there was gunfire on the rooftops. Without missing a beat Mitch rushed to the door and shot-gunned the door handle and lock with one round. He kicked it in and we pushed into the house.

We split into quick-clearing teams by twos, per room, and flooded the house. The front door swung open, covering the doorway into the kitchen, but we could not really see it. I was the No. 1 man and Mitch the No. 2, as he transitioned from shotgun to rifle. A couple of Tabs completed the rest of our four-man team first in. Mitch and I saw an open-door threat in the back of the house as we rushed in, while maintaining site picture on any possible threats. We moved down the doorway. The two guys in the back broke left, while Mitch and I pushed straight across, past a room on our right with an opening to the roof for a gas-fired water tank. Some kind of noise came from the room as we passed it, but we moved straight on to the open-door threat. I was deep into the room at its far wall, and I collapsed my sector of fire, back toward Mitch, who, although designated the No. 2 man, took the position of the No. 3 man in a room-clearing diagram. When room clearing is taught the No. 1 man is never wrong, and makes his choice to go left or right and takes two corners. The No. 2 man goes the opposite of the No. 1 and takes one corner. The No. 3 man goes the opposite of the No. 2 and steps into the room, just far enough to clear the door by about a meter. The No. 4 goes opposite of the No. 3 man, and also just enters the room to clear the door at about a meter. This is how it is trained and it is very choreographed, but combat and building size determines how many shooters can actually fit. The key to remember is it only takes two men to actually clear a room. In this instance, there simply was not enough room to properly conduct room clearing. But we were where we were supposed to be, so he had adjusted mentally very quickly. In the opposite corner from me we encountered one military-aged male and one woman.

OBJECTIVE CRESCENT LAKE

It was an odd situation we encountered within the split second of our entry – the male and female were hugging – the male had pulled her in tight. In all my deployments in Iraq and Afghanistan I had never seen this kind of “show of affection,” if you will, at least not to that extent. Also, the male was fat for his size – well fairly fat, actually he was obese. Being that fat in the Middle East is sometimes considered a sign of wealth. I immediately knew something was not right. We had memorized a number of Arabic words and phrases so I shouted at them, “Put up your hands, let me see your hands!” But to my three challenges there was no compliance, no compliance, no compliance. Everything went down in split seconds, from entry, to clearance, to encountering this couple, to me thinking that I knew my Arabic was terrible, but it had served me well in hundreds of missions and other targets. By now I had asked for compliance four or five times. The situation was tense; gunfire had been exchanged seconds earlier, and we knew about the personal protection Kalaf had in place.

It didn’t feel right but what was I going to do? Drop my rifle, engage in a fist fight, or flip the safety – yes, the safety is always on – and shoot? I thought about the briefing about the potential for a suicide bomber; it’s called a “judgment decision.” I asked for compliance once more as I flipped my weapon off safe to semi. From my angle, my perspective on the couple’s embrace, I could only get a clear sight of half the dude’s face, not his body. All the years of training, all the lessons learnt not only in training but in combat… decisions had to be made, tough ones, and, if wrong, there were lifelong repercussions – from getting kicked out of the regiment to possibly being charged, to feelings of remorse and guilt… split-second judgment calls that change one’s life forever.

I adjusted my sight picture on the rifle to compensate for the distance – he was less than 5 meters away – while I shouted out the final compliance request in Arabic. I calmly compensated for the optics over the rifle bore center line, which was about 4 inches, and raised the sight picture to where I wanted the bullet to impact. My sight picture centered to the base of his hairline; I depressed the trigger and fired as I finished the last statement. I hit him off the left side of the nose. Immediately his tense body position relaxed and he slumped over dead, but I immediately and very quickly put a second round into him. The female was released from the man’s embrace by now and she fell forward. She cleared Mitch’s line of fire and Mitch engaged the dead man with eight to ten rounds and I put seven more rounds into him as well. I called the room “clear.” The female held up her dead companion. Her back was still to me. Mitch yelled for compliance in Arabic yet again but I did not clearly see her actions. But Mitch did. He saw her reach under the dead guy’s buttocks, so Mitch fired off two rounds, then three more, as part of a failure drill – two into the body and then one into the head or neck. I engaged with about five rounds – two pairs to the body, and the final round to the head.

The entire sequence from entry to clearing the room took maybe 60 seconds if that. Meanwhile Rangers had cleared up to the first floor, while other assault squads on the stairs began clearing up the stairs to the roof.

Our platoon sergeant, Justin, another big Ranger at 6 feet tall and a solid, tactically sound leader, came in and now was a lot less stressed and angst-ridden than when we had been setting the pieces in place. Our doc and another Ranger swept in as well. They cleared the kitchen. Our battalion commander wanted to be part of this mission to recapture Abu Kalaf and he too burst into the building. This was his last deployment before a change of command to another job elsewhere. Incredibly, we also had the incoming battalion commander on target as well just as we had barely cleared it. This was a pain when the battalion commander wanted in on the action. Why? Because he was the senior ranking guy on the ground, and he didn’t have to listen to anyone if he didn’t want to. And it was not yet secured! Our outgoing commander, with the self-proclaimed call-sign of “Big Eagle,” as he just been promoted to “full bird” colonel, wanted to fist-bump with me. I responded with, “Hey sir, I’ll give you as many fist bumps as you like but let me finish clearing the building first.”

“Right, right, right,” was his response while laughing.

I moved upstairs and tied in with the rooftop teams and secured the target building within three minutes. Our rooftop guys had killed the target, Abu Kalaf. After getting killed he had fallen down the ventilation shaft into the gas-fired water tank room. This was the mystery sound that Mitch and I had heard earlier as we entered the building.

We conducted a battlefield interrogation on a female detainee; we had killed all the men. The only information we received was that the couple we had killed had shown up that day and that they were from Syria but she did not know who they actually were. While moving the bodies we found out what the deal was regarding the “show of affection” that had me alerted. Turned out the male was sitting on a suicide vest composed of about 7 pounds of Semtex and it was rigged with a couple of Russian hand grenade fuses. Upon discovery of the suicide vest we received a call over the radio that explosives had been found, and that Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) was coming in to deal with it. We were told to avoid the room it was in. The code word was sent for us to move out of the house quickly. The EOD guy came in and left the building sometime later. He moved to a blocking position by a drainage ditch and blew the explosives in place.

Subsequently we picked up a flood of intel traffic about this target. It had stirred up a lot of things and led to more executions of other targets over the next few days. Biometric system intel such as detainee fingerprints helped build the military data biometrics system, useful not only for future missions but also for Homeland Security. We were now able to send digital fingerprints over the internet and if it was in the database you could get a hit. We would get a name, location, and past objective where the individual was fingerprinted; it would also tell us if he had been detained, or just entered into the system as a male who had been on the target area. Since we needed a clear line of sight for the computer, we had to drag all three dead bodies, Kalaf and the Syrian couple, to the driveway to run the biometric system.

As we walked back out of the target building we met Jason who, upon breach, had brought the vehicles to within four blocks and turned the “wagon train” around. He had got it ready so when we had finished the exploitation we were ready to roll back out. The sun slowly came up. This one op had taken up most of the night, but it had been an extremely worthwhile surgical strike. The execution took time but it was the right amount of time.

The “judgment call decision” concerning the mystery couple had turned out to be right and it was a good feeling. I had listened to my gut and paid attention to the culture, as in what is normal and what isn’t. We wrapped up the target and moved off the objective. We called it a night.

Back at base we conducted a debrief. It always sucked when you did not capture the target alive since no additional intel emerged. Although possibly the battalion commander had wanted him dead. But Abu Kalaf had been a foreign fighter – an emir, essentially the head of the mafia in Mosul – and handled not only weapons and ammunition but was also the key organizer of foreign fighters and the ratline networks running throughout the area. Fighters came through those lines along with everything else usually from western Syria, Turkey, or Iran. Now we were not able to exploit his intel. Kalaf had his hands in a lot of these networks. How current would his intel have been because he had been in jail? Well, just because he was a prisoner did not mean he did not run things. The television show Sopranos was big at this time, and Jason, who hailed from Brooklyn, always said, “If the guy is in jail and you think he is not running things from jail you are so wrong.”

The rooftop snipers had killed him right at the go. Kalaf had grabbed a Glock 19 from underneath his pillow. He tried to get to the edge of the rooftop to engage us on the ground where he was killed instantly.

We always tried to teach Ranger privates about judgment calls. A private probably would have erred on the side of not shooting. Mitch later said that I shot half a second before the suicide bomber was going to detonate. So far, all my judgment calls had been correct.

A lot of our success was based on not being complacent and taking every target for what it was – its own beast, and it could be sleeping or rear its ugly head. You always had to snap everyone back to reality because any target that erupted created total chaos. But complacency can and did happen, even to me, a veteran of hundreds upon hundreds of missions. It would only take one night that could change everything and affect everybody.

Some of us talked about the shooting of the couple. Adrenaline was a huge factor in the emotion. Everyone asked how I felt – was I okay? By the time we got back to the FOB the overriding emotion was that I was simply pissed off that someone had tried to blow me up. It is only ever later that the reality of the situation hits you, but in this instance it was definitely a valuable lesson. Anything can happen and will happen. This all sat with me for a couple of days but then I pushed it off to the side; there was work still to be done.

On the same night 2nd Platoon had been looking for one of Abu Kalaf’s moneymen. They successfully netted him and over $100,000 U.S. dollars in their own raid. These two raids put a serious dent in the foreign fighters’ funding and operation capabilities. We executed ten more missions before the end of the deployment. Thanks to this key operation the deployment ended on a fairly high note; all the bad guys had been taken care of and nobody was injured.

No deployment was ever complete without some of our stupid shenanigans. There was some childish stuff early on when some Ranger privates wanted to see how many pairs of ladies’ underwear, found on various objectives, they could stick into the platoon sergeant’s backpack. I think it was 26 by the time Justin, the platoon sergeant, finally opened his pack and the underwear exploded out of it with him yelling, “What the…?” Another time they would hang a pair off the platoon leader’s radio antennae. Finding humor in any situation was important and nobody was better at this than Ranger privates, who were, of course, goaded on by tabbed specialists and team leaders. It was time to go home.