There are three different kinds of manatees: West Indian, West African, and Amazonian. They and their close cousins the dugongs are the only water-living mammals that eat plants. They have two front flippers and a paddle-shaped tail.

Manatees are big, slow-moving animals, which means that they burn energy much more slowly than other mammals and so can’t keep warm in cold water. They can only survive in water that stays above 68°F (20°C) all year round.

Their eyesight is poor, but they can hear well. Touch-sensitive bristles surround their mouth and help them to find the right plants to eat, and muscled lips gather the food into their mouth. Eating plants wears down their teeth, but manatees shed their worn teeth at the front; they’re replaced with new ones from the back.

Manatees can live for thirty years or more. They have just one baby at a time, with a gap of three years in between. A baby manatee stays with its mother for up to two years and doesn’t have babies of its own until it is between six and eight years old.

The manatees in this book are Amazonian manatees. Unlike dugongs, which live in the ocean and are happy in fresh or salt water, Amazonian manatees live only in fresh water, in the Amazon River and the rivers that run into it. Amazonians are the smallest manatee but can still be 10 feet (3 meters) long and weigh 1,100 pounds (500 kilos). Other manatees are gray all over, but the Amazonian manatee has darker, more rubbery skin and a big white patch on its chest.

The Amazonian feeds in a different way from its relatives, too. In the murky waters of the Amazon, there’s too little light for plants to grow under the surface, where other manatees find their food. So Amazonian manatees feed mainly on floating plants, nibbling at them from underneath or sometimes poking their heads out of the water.

Water levels in the Amazon can vary between the wet and the dry season by as much as 46 feet (14 meters), which is nearly twice as high as an average two-story house. In the wet season, the river floods the forest and there’s a lot of surface where floating plants can grow. Manatees eat a lot and get fat! But in the dry season, the river shrinks, and manatees must retreat to lakes or deep parts of the river, where the water stays deep enough to hide them.They survive there by living off their fat reserves.

Unfortunately for manatees, in addition to being big and slow-moving, they also taste good to humans, rather like pork. So everywhere they are found, manatees have been hunted. They also get tangled up in fishing nets, injured or killed in collisions with the propellers of motorboats, and poisoned when rivers are polluted. Their low breeding rate means that manatee numbers can’t recover quickly if too many are killed.

Amazonian manatees have been hunted by humans for at least five hundred years, especially in the dry season, when many manatees can be found together taking refuge in lakes. They can be herded using boats and then speared or caught in nets. Sometimes, many manatees are killed at once.

Calves, orphaned when their mothers are killed or caught in nets because they were too young and inexperienced to avoid it, are sometimes kept in captivity until they are big enough to eat or are traded as pets.

There are more motorboats and nets in the Amazon than ever before, and manatees are now an endangered species because people still hunt them, even though it’s illegal.

One way to keep manatee numbers from falling is to return orphaned calves to the wild, which is happening in many parts of the Amazon. But the hunting and careless use of nets still continue, and calves are still orphaned.

The real problem is that in places where food and money are scarce and the police can’t see what’s going on, it doesn’t work to tell people not to kill manatees; they have to want not to.

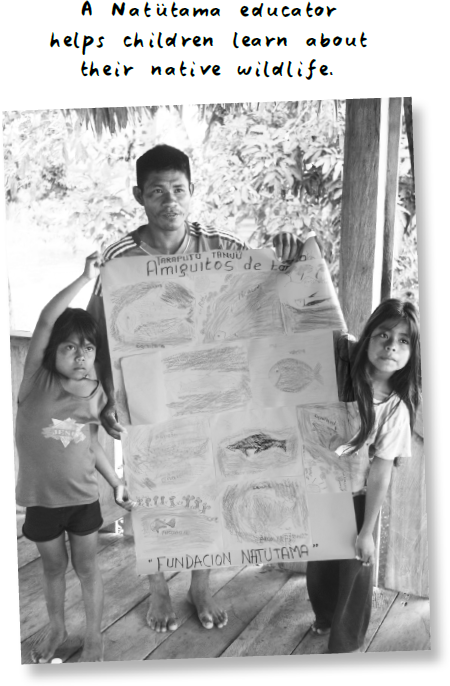

In Puerto Nariño, a small town on the Amazon in Colombia, an organization called Natütama has been working with local people to encourage them to love manatees and not to hunt them.

Natütama’s work began with a real-life incident very like the story in this book. An injured manatee calf was rescued and passed on to Sarita Kendal, cofounder of Natütama. Sarita and her helpers worked over two years to restore the calf to health, feed it, care for it, and finally to wean it, so that it would be able to survive in the wild. The calf was named Airuwe, the Ticuna word for manatee.

Many people in Puerto Nariño got involved in Airuwe’s care. He became a celebrity, and when it was time for him to be returned to the river, almost all the village came along. He was fitted with a radio collar so that Sarita and her team could track him and check that he was safe. At the same time, the collar gathered valuable information about manatee behavior. For several months, Sarita and a team of local fishermen spent hours every day watching Airuwe and learning about manatees.

Eventually Airuwe’s collar dropped off, so it wasn’t possible to keep track of him. But when a manatee was killed by the one local fisherman who had always been determined to keep hunting manatees, he was reported to the police and fled from the village.

Since that time, no one in Puerto Nariño nor its neighboring villages has killed a manatee. Fishermen and their families say that they will never hunt manatees, as they want their grandchildren to be able to see manatees as they themselves have always done.

Now all schoolchildren from Puerto Nariño, and from communities up and down the river and across Colombia, visit Nat¨utama’s thatched headquarters. They learn about manatees and the animals and plants that share their environment by visiting an exhibition of the manatees’ underwater world and through songs, games, stories, and puppet shows. Natütama holds gala open-house days and takes part in local festivals. They even bake manatee cookies just like the ones in the book. Natütama workers visit villages across the border in Peru and Brazil to remind people of their connection with the natural world and the value of wildlife. Fishermen are employed to help monitor the small, precious population of about 35 manatees in the Puerto Nariño area, and they report over 500 sightings of manatees every year. Natütama’s conservation work grows out of the community around it and encourages a culture of respectful stewardship, rather than exploitation.

Sarita was never sure if Airuwe had been killed. But to this day, people tell her that they’ve seen him upriver.

If you’d like to help keep manatees in the Amazon, you can support organizations like Natütama.

E-mail: fundacionnatutama@yahoo.com