The story of Blackbeard really begins with a peace treaty, and a fleet of Spanish treasure ships. The signing of this treaty and the wrecking of the Spanish treasure fleet took place within two years of each other, and the two events conspired to produce a wave of crime that threatened to cripple the fragile economy of the American colonies. Today this wave of criminal activity is often referred to as ‘The Golden Age of Piracy’. To the victims of pirates such as Blackbeard there was nothing ‘golden’ about it.

The signing of the Peace of Utrecht in April 1713 marked the end of the fighting between France, Spain, Great Britain, Portugal and Holland in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14). While the war between France and Austria dragged on for another year, the conflict between Europe’s principal maritime powers was now over. For more than a decade the Caribbean basin had been a theatre of war, and privateers of all these nations had sailed its waters, preying on the merchant shipping of their nation’s enemies. When news of the peace treaty reached the Americas that June, all these lucrative privateering contracts were rendered null and void. Thousands of well-armed seamen found themselves out of work, and many were unwilling to return to their previous mundane and poorly paid employment as merchant seamen. Privateering had given them a taste for plunder.

Effectively privateering was nothing more than state-sponsored piracy. When a war began a sea captain or ship owner could apply to his government for a letter of marque. The aspiring privateer agreed to attack the merchant shipping of his country’s enemies, and to take the prizes into a friendly port where the ship and cargo would be sold. This was all perfectly legal in time of war. In return the government got a share of the proceeds – the level was usually set at 10 per cent. Obviously this was an extremely lucrative arrangement for everyone except the foreign ship owners, and of course foreign governments were doing exactly the same thing. It has been estimated that during the War of the Spanish Succession more than 300 privateers of various nationalities were operating in American waters, from Newfoundland down to Brazil. Most based themselves in the Caribbean, where the trade in rum, sugar and slaves ensured there was no shortage of prizes.

Profits were high – the owner of a ‘private man-of-war’ could recoup the cost of investment in just one short successful cruise. Privateering ships earned small fortunes for their owners and captains, but the crews were also well rewarded. Rather than receiving a regular wage like normal seamen they received a share of prize money – the money raised from selling the captured ship and its cargo. A successful privateering crewman could make more money in a single cruise than he could during a lifetime on board a merchant ship. It was little wonder that when the war ended many were tempted to continue plundering ships, regardless of the legality of their actions. While there might have been a peacetime boom in mercantile activity, many privateersmen were reluctant to return to the poor wages and harsh discipline of the merchant service.

For the British the centre of privateering activity in the Caribbean was Jamaica. Port Royal had been an infamous buccaneering base during the 17th century, when English, French and Dutch seamen used this roistering harbour while raiding the Spanish Main. Much of their plunder was spent in the port’s taverns and brothels, at a time when Port Royal was being labelled ‘The Sodom of the New World’. A combination of a devastating earthquake and tsunami in 1692 and a peace treaty in 1697 brought this roistering period to an end, but the harbour remained a useful haven for privateers a decade later when war returned to the Caribbean.

We don’t know it for sure, but Blackbeard was almost certainly based there during the last years of the War of the Spanish Succession. The trouble with pirates in this period is that, like most seamen, very little is known about them until they crossed the line from law-abiding sailor to dangerous criminal. Blackbeard’s real name was almost certainly Edward Teach, but he only appears in the historical record at the very start of the ‘Golden Age of Piracy’. His first biographer, Captain Charles Johnson, writing in 1724, claimed that ‘Edward Teach was a Bristol man born, but had sailed some time out of Jamaica in privateers, in the late French War’. He added that ‘he had often distinguished himself for his uncommon boldness and personal courage’, but that ‘he was never raised to any command’.

By 1715 the mean streets of Port Royal were filled with seamen down on their luck, or men squandering the last of their privateering money before they left to seek gainful employment elsewhere. Then, appearing like manna from heaven, came the news of an epic disaster. For almost two centuries the Spanish had sent an annual fleet of treasure ships from the Caribbean to Spain. They carried a fortune in silver ingots, gold bars, silver and gold coins, plus emeralds and spices. The Spanish had come to rely on these ships arriving in Seville. Only three times – in 1554, 1622 and 1628 – had the fleet failed to reach Spain. In 1628 the fleet had been captured by the Dutch, and on the other two occasions it was struck by a hurricane and wrecked. That was exactly what happened in 1715. The treasure flota left Havana on 24 July, and a week later it was threading its way through the Bahamas Channel, between Florida and the Bahamian archipelago. On the evening of 30 July the ships were hit by a fearsome hurricane, which dashed the fleet against the reefs and sandbars of the Florida coast. Only one ship survived, and she limped back to Havana with the news.

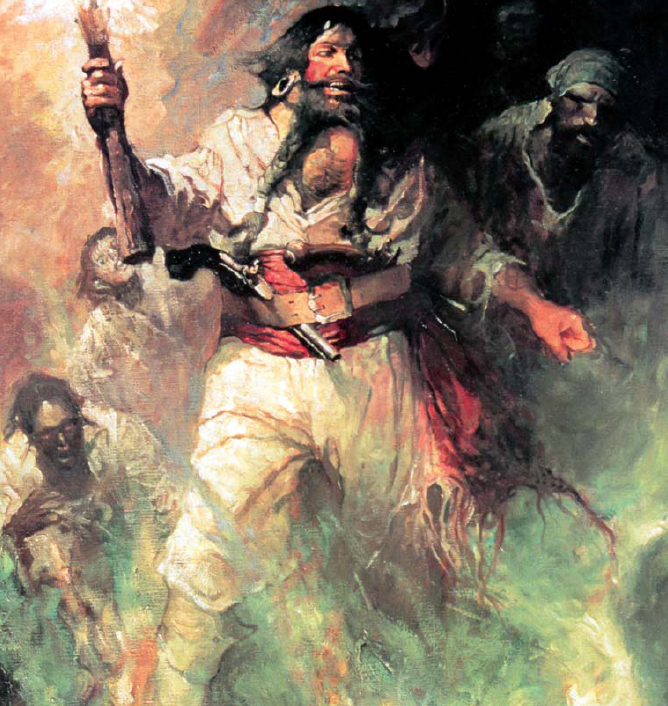

In this depiction of Blackbeard by Frank Schoonover, the pirate captain has tied his beard ‘with ribbons, in small tails’ as described by Captain Johnson. While many depictions of Blackbeard are largely fanciful, all draw on Johnson’s description for their inspiration.

A rescue expedition was duly sent out, not to rescue any survivors but to salvage what they could of the lost treasure. Unfortunately for the Spanish, news of the disaster had also reached Jamaica. In November 1715 Governor Hamilton of Jamaica sent two sloops on an anti-piracy patrol, under the command of Captain Henry Jennings, a former privateer. Unbeknown to the governor, Jennings rendezvoused with three other sloops crammed with ex-privateers, and then set off in search of Spanish treasure. We are reasonably sure that Edward Teach took part in this venture and was on board one of the five Jamaican sloops.

Jennings and his 300 adventurers landed close to the wrecked ships, and attacked the salvage camp, driving off the 60 Spanish guards. They then helped themselves to the treasure, and returned to Jamaica with their sloops filled with 60,000 pieces-of-eight. Back in Jamaica Governor Hamilton wisely turned a blind eye to the celebrations that ensued. By then treasure fever had swept the Caribbean, and hundreds of former privateers and other sailors joined Jennings’ men. The Spanish were furious, and sent troops to protect their salvors. They also lodged a formal complaint with Governor Hamilton, who was forced to intercede. Before the troops arrived Jennings struck again, and this time he doubled his haul. That was the last of the plunder – the Spanish sent two large warships to carry home what remaining treasure they could find.

New Providence is the small island to the left of the phrase Tropique du Cancer in this detail from an early 18th-century French map of the Atlantic seaboard of North America. Ocracoke is below Cap Hatteras, to the left of the word MER.

While this engraving shows the pirate George Lowther, in the background a group of pirates can be seen, wearing the clothing worn by most seamen of this period. The wearing of sashes and headscarves is an inaccurate, modern addition to early 18th-century pirate dress.

By then – the spring of 1716 – Jennings was persona non grata in Jamaica, as he had disobeyed the governor’s explicit orders. He needed a new base. He settled on the island of New Providence in the Bahamas, a place that lay beyond the reach of the authorities, and which had already become a minor haven for former privateers turned pirate. The arrival of Jennings turned this small pirate haven into a boom town. The pirates who had already based themselves there were led by Benjamin Hornigold, a former privateer who was now a pirate with scruples. He tried to avoid attacking British ships and generally adhered to the terms of his old privateering ‘letter of marque’. The French and the Spanish, though, were fair game. He had about 200 men under his command, and they operated in the nearby Bahamas Channel, between the Bahamas and Florida.

Jennings and his men soon turned to piracy, and many joined Hornigold’s crew. By the summer of 1716 New Providence was a hive of illegal activity, with treasure hunters using the islands to raid the wreck sites, while others made a living through piracy. The result was a marked increase in the number of piratical attacks, both in the Bahamas Channel and in the Florida Strait. Soon these Bahamian pirates were ranging as far afield as the seaboard of Britain’s American colonies, and the islands of the West Indies. On 3 June Governor Spotswood of the Virginia colony wrote to the Council of Trade in London, complaining about this upsurge in piracy. He added that pirates had taken over the Bahamas.

By early 1717 it was reported that there were over 500 pirates in New Providence, and at least a dozen small pirate vessels, mainly sloops and brigantines. Makeshift taverns and brothels were established there, and merchants from Jamaica and the West Indies visited the islands to buy the pirate plunder at knock-down prices. Most merchant ships of the time carried mundane cargoes such as tobacco, rum, cotton, sugar or timber. If the cargoes couldn’t be consumed by the pirates themselves they were worthless, unless they could find merchants unscrupulous enough to buy stolen goods. This is exactly what happened in New Providence.

So, what of Blackbeard – Edward Teach? His biographer Captain Johnson reported that ‘He went a-pirating, which I think was in the latter end of the year 1716, when Captain Benjamin Hornigold put him in a sloop that he had made prize of, and with whom he continued in consortship till a little while before Hornigold surrendered’. In other words, Blackbeard started his piratical career as one of Hornigold’s crew, based in New Providence during late 1716. It also seems clear that after Hornigold realized the potential of his recruit, he became Blackbeard’s mentor, and eventually gave him command of one of his prizes.

Then in March 1717 we have an official confirmation of Blackbeard’s new status. Captain Munthe of South Carolina ran his sloop aground on the western fringe of the Bahamas, and while he was freeing his vessel he questioned local fishermen about pirate activity in the area. They told him that five main pirate captains were operating from New Providence, including Hornigold, Jennings and ‘Thatch’. The latter, who commanded a six-gun sloop and 70 men, could only be Edward Teach. He was still sailing in consort with Hornigold, and that spring their two sloops cruised off the Atlantic seaboard, capturing several prizes, and generally making a nuisance of themselves.

What ended this association with Benjamin Hornigold was a royal pardon. The British Government had offered to pardon any pirates who willingly gave themselves up. Hornigold, who always claimed he was a privateer, not a pirate, decided to accept the offer. His crew rebelled at this, and Hornigold was deposed as captain. It was probably at this point that Blackbeard decided to forge his own path. Certainly by September he was cruising independently, as a pirate captain in his own right. On 29 September 1717 he attacked the sloop Betty of Virginia, which was returning home with her hold laden with wine. The pirates drank their fill, and then sank their prize, leaving the crew a boat in which to row ashore.

So began the cruise of Captain Edward Teach, who lacked Hornigold’s scruples when it came to British or colonial American prizes. What followed was a voyage that would make Blackbeard’s piratical name, and would threaten to bring the maritime trade of Britain’s North American colonies to a standstill. The legend of Blackbeard was about to begin.

This anchor was recovered from the wreck of Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge, which foundered in Topsail Inlet (now Beaufort Inlet), near the modern port of Beaufort, NC. The site has produced a wealth of artefacts, most of which are now on display in the North Carolina Maritime Museum.

In late September 1717 Blackbeard was off the Virginia Capes, where he captured the sloop Betty. With hindsight he would have been better cruising off a colony where the governor was less enthusiastic in waging a war against piracy. All Blackbeard achieved there was to get his crew drunk, and annoy Governor Spotswood of Virginia. We don’t know the name of Blackbeard’s pirate sloop, but in early November the Boston News Letter printed a report from a Captain Codd, who had been sailing from Dublin to Philadelphia when he was attacked, ‘by a pirate sloop called Revenge of 12 guns, 150 men, commanded by one Teach.’

Blackbeard was clearly coming up in the world – during the summer he had doubled the size of his crew, and the number of guns he carried. He let Codd’s ship go, largely because she was carrying indentured servants. Many of these might well have joined Blackbeard’s crew – his crew increased largely thanks to volunteers recruited from captured merchantmen. The same newspaper mentioned five other pirate attacks which took place off the coast of Delaware in mid-October, and although Teach wasn’t named we can be fairly certain that he was responsible. In one of them the pirates kept their prize, the sloop Sea Nymph from Bristol, outward bound from Philadelphia to Oporto. Every time he captured a ship, Blackbeard recruited new crewmen from it. Now he had a second ship for these new recruits to crew.

The Sea Nymph didn’t last long – a week later Blackbeard captured a ‘great sloop’ bound from Curaçao with a cargo of cocoa. The beans were thrown overboard, but the pirates kept this new vessel, and gave the Sea Nymph to Captain Goulet and his men, who sailed on to Philadelphia. This example of ‘trading up’ was a typical ploy of pirates of the period. Soon Blackbeard would do it again, but in a much more spectacular fashion. Before the Sea Nymph was over the horizon the pirates had captured three more ships. It was suggested in the newspaper that Blackbeard’s force consisted of more than one sloop. This fits in with the tally of his prizes. However, the mention of his ship name – the Revenge – shows that Blackbeard didn’t confine his attacks to merchant ships.

In the Boston News Letter article about Captain Codd’s encounter with Teach, it mentioned that ‘On board the Pirate Sloop is Major Bennet, but has no command; He walks about in his morning gown, and then to his books, of which he has a good library on board’. This was a misprint for Major Stede Bonnet of the Barbados militia. A few months earlier he decided to abandon his wife and plantation, and to become a pirate. He actually bought a sloop – the Revenge – and hired a crew. Real pirates captured their ships – they didn’t buy them. Somewhere off Virginia or Delaware Bonnet fell in with Blackbeard, who decided to take the major under his protection. Effectively this meant Blackbeard commandeered his sloop and his crew, and Bonnet became a virtual prisoner on board his own vessel.

By the end of October Blackbeard was off New Jersey. Winter was approaching, and like many pirates Blackbeard favoured a pattern of cruising off the Atlantic seaboard in summer and then heading south into the warmer waters of the Caribbean for winter. The hurricane season lasts from June to November, which was another reason pirates often avoided the Caribbean during this period. Consequently Blackbeard decided to set a course towards the south, passing down the eastern side of the Bahamas to reach the Leeward Islands. At this point it seems that Blackbeard had two sloops under his command – the Revenge and the ‘great sloop’. It seems Blackbeard’s original sloop – the one given to him by Hornigold – had returned to New Providence.

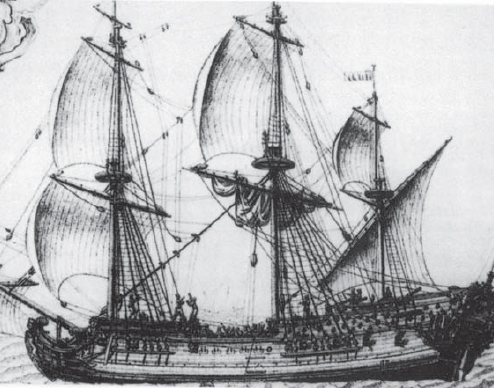

His two remaining vessels reached the Caribbean in early November, and by the 17th they were some 60 miles off Martinique. A lookout spotted a ship on the horizon, and Blackbeard gave chase. She was eventually overhauled and surrendered after a token fight. She turned out to be the French slave ship La Concorde of 200 tons, bound from Nantes to Martinique.

He took his prize to a secluded anchorage off the nearby island of Bequia, and there he set about converting La Concorde into the ultimate pirate ship. The slave ship carried 16 guns, but Blackbeard carried spare guns in the holds of his two sloops – ordnance taken from prizes. His men cut extra gun ports in the slave ship, and got rid of her forecastle and quarterdeck, to create a more efficient fighting platform. By the time they finished, the new pirate flagship carried no fewer than 40 guns, which made her more than a match for any merchantman she encountered, and more powerful than most of the warships in American waters. Blackbeard named his new flagship Queen Anne’s Revenge.

This early 18th-century engraving of a French merchant ship depicts a three-masted vessel of a similar size and appearance as La Concorde, the slave ship from Nantes which Blackbeard captured, and then converted into the Queen Anne’s Revenge.

Leaving the slaves on Bequia, Blackbeard began his cruise through the Leeward Islands, and captured his first prize a week later. Next was a merchant ship from Boston – the Great Allen – which was plundered then burned. Four more sloops followed, all captured between St Vincent and Anguilla. The last of these was the Margaret, commanded by a Captain Bostock. In his report of the attack Bostock claimed that the pirates attacked him with a large ship and a sloop, and that the flagship was crewed by 300 men ‘with much gold dust aboard’. Then he described the pirate captain, who he called ‘Captain Tach’. This pirate was ‘a tall spare man with a very black beard which he wore very long’. As a result, this pirate captain with his powerful ship was about to earn a nickname that would strike terror throughout the Americas. Blackbeard had come of age.

During these attacks Teach learned that a powerful British warship was out looking for him – the 30-gun Scarborough. While Blackbeard’s Queen Anne’s Revenge had more guns, her crew was largely untrained in gunnery, and they would have little chance in a straight fight with a powerful British frigate. His biographer Captain Johnson has Blackbeard fighting the Scarborough, but this is pure invention. The two ships never met. Sensibly Blackbeard decided to quit the Leeward Islands before he was cornered by the Scarborough, and he headed towards Hispaniola, where he sought refuge in Samana Bay. There he probably careened his ships – weeds and barnacles were scraped off the hulls – to make them sail faster. The pirates no doubt also celebrated Christmas by eating, drinking and enjoying themselves.

In February Blackbeard set off westwards towards the Gulf of Honduras, and the coast of Central America. This was usually a busy place, as ships regularly anchored in the bay to collect cargoes of logwood. Blackbeard probably avoided Jamaica, where the Royal Navy maintained a guard ship, and by late March he reached what is now Belize. Off the Turneffe Islands he captured a Jamaican sloop called the Adventure, and kept the fast 80-ton vessel for himself. Therefore Blackbeard commanded three craft by the time he reached the logwood anchorages. The three vessels fanned out to cover a larger area, and four rich prizes were caught in their net – a three-masted sailing ship called three-masted sailing ship the Protestant Caesar, and three more sloops. All these prizes were plundered and burned.

By the end of April Blackbeard was ready to sail north again. He wanted to leave the Caribbean before the start of the hurricane season, and so he headed north through the Yucatan Channel, and then rounded the western tip of Cuba. He sailed along Cuba’s northern coast to reach the Florida Straits, and off Havana he captured a small Spanish sloop. He kept her, which meant that as his force entered the familiar waters of the Bahamas Channel Blackbeard had three sloops under his command, as well as his 40-gun flagship. With such a powerful squadron at his disposal Blackbeard must have felt invincible.

The ‘gentleman pirate’, Major Stede Bonnet, was a plantation owner and militia officer from Barbados who gave up his prosperous but dull life to become a pirate. After effectively being held prisoner by Blackbeard, Bonnet was abandoned by him at Topsail Inlet.

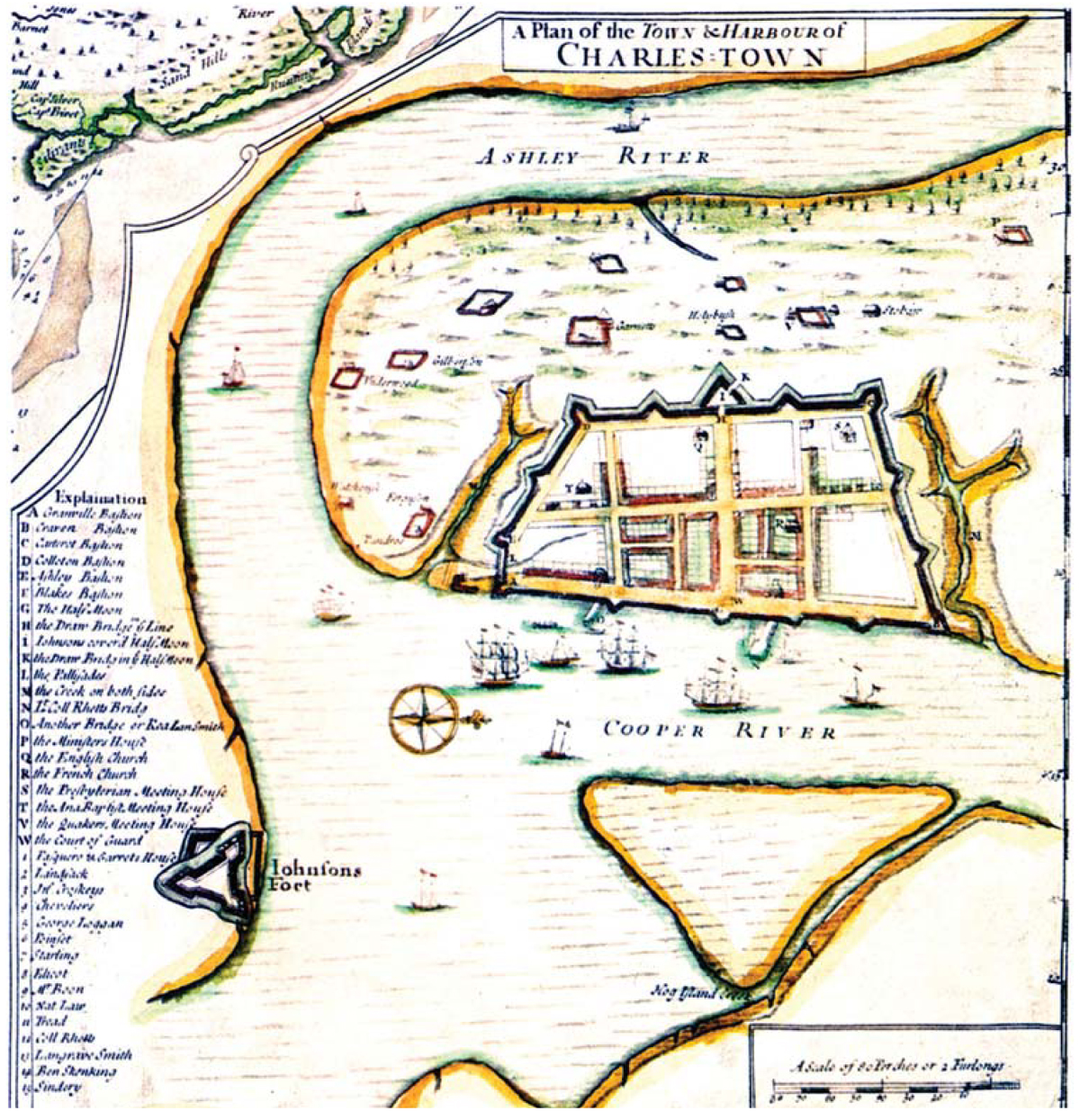

This was probably why he felt confident enough to undertake his most ambitious attack yet. On 22 May 1718 the pirate flotilla appeared off Charles Town (now Charleston), in the South Carolina colony. A long sandbar separated Charles Town Harbour from the sea, and there was only one gap in it deep enough to allow large ships to pass. Even then the ships usually needed the help of a pilot. Blackbeard positioned his pirate squadron just outside this channel, and effectively placed the port under blockade.

The pirates’ first victim was the pilot boat that came out to help the new arrivals past the Charles Town bar. She was accompanied by the Crowley, a large merchantman bound for London. Soon both vessels were in the hands of the pirates. Two more outward-bound ships were captured the following day, one of them the William, a large British merchantman. After that the authorities realized what was happening, and the remaining ships in Charles Town remained trapped in the harbour. This was an incredible act for a pirate. Until now, pirates had preyed on individual ships on the high seas. Not since the days of the 17th century buccaneers had anything so audacious been attempted. Now Blackbeard was holding a whole port to ransom, one of the richest in Britain’s North American colonies.

That, of course, was his intention. He planned to make whatever money he could from the situation, and then disappear before the Royal Navy could send warships to break the blockade. The nearest Royal Navy squadron was in Virginia’s James River. It would take a week to contact them, and another week for the warships to reach Charles Town. In the meantime the pirates were in control. Captain Johnson described the effect this was having on the city’s inhabitants. The blockade ‘struck a great terror to the whole province of Carolina … that they abandoned themselves to despair, being in no condition to resist their force’. Trade was completely disrupted – until Blackbeard left, no ship could get in or out. The city fathers awaited the pirates’ demands.

When they came they were surprisingly lenient. Blackbeard sent some of his captives ashore with a demand for a chest of medicine. The pirates who escorted them added that if this simple demand wasn’t met then their companions ‘would murder their prisoners, send up their heads to the governor, and set the ships they had taken on fire’. While the governor of the South Carolina colony sent for help, he and his advisors considered their options. The port was defended by artillery batteries and local militia, but their effectiveness was questionable. The easiest thing was to agree to Blackbeard’s demands. So a medicine chest valued at £300–£400 was sent aboard the Queen Anne’s Revenge, and for the moment the pirates seemed satisfied.

In fact Blackbeard had already looted a small fortune – around £1,500 – from the passengers of the Crowley, as well as money and supplies from the other ships. To demand a ransom from the city would involve lengthy negotiation, and Blackbeard knew that time was not on his side. The importance of the medicine has never been fully explained, but the most likely reason is that the pirate captain and his crew might have contracted a disease; either a venereal one from their winter stay in Hispaniola, or else the flux – yellow fever – from their time in the Gulf of Honduras. Whatever the reason, Blackbeard seemed pleased with his ransom and his ships raised their blockade, and sailed away over the horizon.

Blackbeard knew that this daring assault would raise a whirlwind of indignation, and he would be branded the most notorious criminal in the Americas. He needed somewhere to lie low for a while, where he could divide his plunder and plan his next move. He must have considered his options. He could sail off to the north, to prey on the untouched waters of New England, or he could cross the Atlantic to cruise the slaving grounds of West Africa. Both of these options entailed a fair degree of risk. Instead, Blackbeard began formulating another scheme – one that would give him a chance to treble his profit, and would give him immunity from the authorities. After his greatest triumph, Blackbeard was going to give up his piratical ways.

Charles Town (now Charleston, SC) lay at the far end of a wide natural harbour, which was separated from the sea by a long sandbar. By blocking the only navigable channel through it, Blackbeard managed to blockade the port, one of the most prosperous in Britain’s American colonies.

The pardon offered to pirates was still on offer, but Blackbeard had to be careful where he went to accept it. After all, his actions off Charles Town meant that technically he was ineligible, as he was still an active pirate. Since he left the Bahamas Hornigold and others had accepted a pardon, and were actively supporting the establishment of British rule there. That ruled out a return to his old base. Governor Spotswood of Virginia and Governor Hunter of New York were vehement in their opposition to what they saw as ‘diehard’ pirates such as Teach. Clearly, Blackbeard couldn’t return to South Carolina either, as the governor there wasn’t going to forgive the blockade of his main port. That left the colony of North Carolina. The problem was that the North Carolina colony was one of the least developed places on the Atlantic seaboard. Its one port – Bath Town – sat on an inland sound, protected from the sea by a line of islands and shifting sandbars. It would be the ideal place to establish a new base, while pretending to turn his back on piracy, but first Blackbeard had to get rid of the Queen Anne’s Revenge. It was too large to pass through North Carolina’s Outer Banks, and while it remained afloat it represented a direct threat to the Royal Navy.

Blackbeard came up with a novel solution. After leaving Charles Town he sailed north past the mouth of the Cape Fear River, and by the start of June he was approaching Cape Lookout, which marked the southern tip of the Outer Banks. Moving closer inshore he reached Topsail Inlet (now Beaufort Inlet), near the modern port of Beaufort, North Carolina. There was no town there in 1718 – only a handful of huts belonging to seasonal fishermen. The channel leading to the anchorage beyond the inlet was narrow – just 300 yards wide. Undeterred, Blackbeard sailed his flagship into the channel, with his sloops following on behind.

All of a sudden the Queen Anne’s Revenge ran hard aground. Blackbeard called out to Israel Hands in the sloop Adventure, and asked him to tow the larger ship off the sandbar. Instead the Adventure ran aground too. It soon became clear that there was nothing to be done – the Queen Anne’s Revenge was stuck fast, and was as good as lost. It is virtually certain that this is exactly what Blackbeard had intended. It was all part of his plan for ‘downsizing’ his piratical operation. Next, Blackbeard sent Major Bonnet off to Bath Town in the small Spanish sloop, to meet the colony’s governor, and to arrange a provisional pardon.

As soon as Bonnet had sailed off, Blackbeard moved the plunder from his flagship to a small captured sloop. Next he landed most of his crew on the beach at Beaufort, and marooned those who remained loyal to Bonnet on a small island. This done, he stripped the Revenge of anything useful, and sailed off to the north. When Bonnet returned a week or so later he discovered that Blackbeard had abandoned over 200 of his men, and absconded with all the plunder. It was a dastardly move, even for a notorious pirate. Worse, Bonnet had also paved the way for Blackbeard to give himself up to the authorities. The major turned pirate was left penniless, and surrounded by pirates baying for revenge. After a few weeks of fruitless pursuit Bonnet eventually succumbed to the wishes of these men, and turned pirate again. Meanwhile Blackbeard was well on his way to becoming a pardoned man.

Blackbeard made his way to Bath Town, and in mid-June he accepted the King’s Pardon from Governor Charles Eden of North Carolina. Officially, he and his 30 remaining men had turned their back on piracy. Unofficially he had already split the plunder with them, and they all realized that they were merely biding their time, waiting for the right time to resume their criminal career. Meanwhile the two taverns in the port would benefit from these boisterous and wealthy new customers, and their notorious captain became a source of curiosity in the colony, as he entertained the wealthier colonists with tales of his misdeeds. Others were less convinced that Blackbeard had indeed turned his back on his criminal past. In particular Governor Spotswood in neighbouring Virginia was sure that Blackbeard was up to no good. As soon as he had evidence, he would act, and rid the world of this dangerous character once and for all.

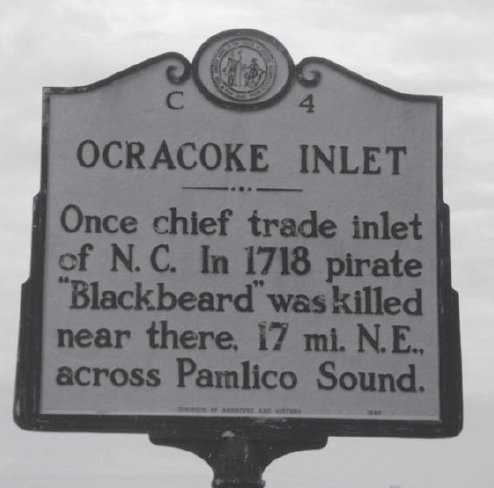

Numerous historical markers in North Carolina help identify the key locations in the Blackbeard story. This one is on Cedar Island, NC, near where passengers now board the ferry crossing Pamlico Sound to Ocracoke Island.