Ironically, the reason Edward Teach was able to gain a pardon for his crimes was due to an anti-piracy policy adopted by the British Government. Faced with a dramatic upsurge in the incidence of piracy, the government considered its options. The Royal Navy had already been reduced in size after the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, and the Admiralty’s budget had been cut. This meant it was unlikely that the navy could significantly increase its presence in American waters – at least not immediately. The other option was to reduce the number of active pirates in the Americas by offering a pardon to those willing to renounce their criminal ways.

This policy wasn’t new. The government of King William III had introduced the scheme during the few brief years of peace after the last war with France, between 1697 and 1701. It worked then, and allowed the Royal Navy (working together with the Dutch) to concentrate their resources on the pirates who remained at large. Essentially it was a scheme designed to reduce the number of active pirates on the high seas. It certainly wasn’t designed to reward those who accepted the pardon by letting them abscond with their plunder, but for the pirates that was the real attraction.

This was why Blackbeard’s pirate mentor Benjamin Hornigold was so keen to accept the latest version of the pardon when it was issued in September 1717. He and Henry Jennings had made a small fortune through piracy and illegal treasure hunting, and when word of the royal proclamation reached the Caribbean that December they both saw a way of keeping their money without running the risk of capture and execution. Word of this scheme had already been discussed in the British and colonial American newspapers, so the proclamation came as no surprise to Hornigold and the others. What they didn’t know until they read the details of it for themselves were the terms attached to it.

The document itself was impressively titled a ‘Proclamation for Supressing Pyrates’, and it stated that since 24 June 1715 the New Providence pirates had ‘committed diverse piracies and robberies on the high seas, in the West Indies, or adjoining to our plantations’. The date was important – it was when the Spanish treasure fleet set sail from Havana. The implication is that the authorities in London recognized Jennings’ attack on the salvage camp as marking the start of this recent pirate scourge. Then came the terms:

Alexander Spotswood (c. 1676–1740), the acting governor of the Virginia colony, was the man behind the attack on Blackbeard. Essentially he realized that if Governor Eden of North Carolina was unwilling to deal with the pirate, then he would have to intervene.

We have thought fit … to issue this, our Royal Proclamation, and we do hereby promise and declare that in case any of the said pirates shall, on or before the 5th September in the year of our Lord 1718, surrender him or themselves to one of our principal Secretaries of State in Great Britain or Ireland, or to any Governor or Deputy Governor of any of our plantations beyond the seas; Every such pyrate or pyrates so surrendering him, or themselves, aforesaid, shall have our gracious pardon, of and for such, his or their piracy or piracies, by him or them committed before the 5th of January next ensuing.

Effectively this meant that Hornigold or any other pirate who applied for a pardon to a British colonial governor would be granted one, on two conditions. First, they had to apply within a year of the promulgation of the royal proclamation – by 5 September 1718. Secondly, any piratical attack carried out after 5 January 1718 wouldn’t be forgiven, and the perpetrator would be ineligible for a pardon. Strangely, it seemed to give the pirates four months of grace, when they could attack at will, and still be pardoned afterwards. One would have thought this gave the pirates carte blanche to plunder freely, but in fact copies of the proclamation only reached Jamaica in early December 1717, and it was the end of the month before Jamaican traders brought them to New Providence. That meant the pirates had no time to enjoy a last swansong if they wanted to receive the king’s pardon.

The arrival of Governor Woodes Rogers in New Providence marked the end of piracy in the Bahamas. As a former privateer he understood how to deal with these privateers turned pirates, and enlisted the help of Benjamin Hornigold to help keep them in line.

This scheme was only part of the story. In effect it was the carrot. The proclamation also contained a very big stick. It continued: ‘We do hereby strictly command and charge all our Admirals, Captains and other officers at sea and all our Governors and commanders … to seize and take such of the pyrates, who shall refuse or neglect to surrender themselves accordingly’. It went on: ‘We do hereby further declare, that in case any person or persons, on, or after the said pyrates … shall have and receive a reward’.

This reward – a bounty on the head of any captured pirates – was set at £100 for a captain, £40 for a quartermaster, master or gunner, and £20 for any other pirates in the crew. This reward was earned for ‘causing or procuring discovery or seizure’. If one of the pirate crew turned informer, and handed their own captain over to the authorities, then the reward was doubled – they could earn a pardon, and a reward of £200. In 1718 that was the equivalent of £40,000 (US $60,000) today.

The pirate Charles Vane was the leader of the ‘diehards’ from the Bahamas who refused to accept Governor Rogers’ pardon. He and his men spent a week or so in Blackbeard’s company on Ocracoke in September 1718. He was eventually caught, and was executed in 1721.

While it wasn’t actually said in the proclamation, the stick wasn’t just a matter of offering blood money. It was matched by a policy of encouraging colonial governors and naval captains to be proactive, and to hunt down those pirates who refused to apply for a pardon. With fewer pirates to deal with the Royal Navy could therefore concentrate its limited resources on the ones who remained at large. By finding and capturing them they would then send a message to other would-be pirates, or to those who might consider reverting to their old ways. It had to be shown that piracy was not a sensible career option.

This was why hunting the pirates wasn’t necessarily the end of it. Ideally many of the pirates would be captured rather than killed, which then raised the possibility of a public trial – where the outcome was rarely in any doubt – and a very public execution. Even this wasn’t the end of it. After the public hanging the bodies of pirates were often liberally coated in pitch or tar to preserve the corpse, and then stuck inside iron cages, which were hung on gallows at the entrance of the harbour where the trial and execution took place. This was another very visible way of reinforcing the message that piracy didn’t pay.

When news of this proclamation reached New Providence in December 1717 it divided the pirate community. It has been estimated that there were around 800 pirates based there at the time – a significant increase since the start of the year. For the same period the total number of pirates operating in American waters was probably double that – historians have placed the number at somewhere between 1,500 and 2,000. In other words, if the authorities could deal with the pirates in the Bahamas, then they would eradicate half of the pirate problem.

Benjamin Hornigold and Henry Jennings both planned to accept the pardon, but for two different reasons. Hornigold had been deposed by his crew, who rebelled against his limiting attacks to French and Spanish ships. For him the notion that he was still acting as a privateer was important, and set him apart from other pirates. The pardon offered a way for him to recover some of his lost dignity, and to regain his standing in New Providence. For Jennings the motive was more mercenary – he saw a way to retire with his plunder intact. Both men felt that the British authorities would be more willing to accept their contrition if they also encouraged their fellow pirates to follow their example. Captain Johnson recorded how they set about convincing their fellow pirates:

They sent for those who went out a-cruising, and called a general council, but there was so much noise and clamour that nothing could be agreed on. Some were for fortifying the island, to stand upon their own terms, and treating with the government on the foot of [as] a commonwealth. Others were also for strengthening the island for their own security, but were not strenuous for these punctilios, so that they might have a general pardon without being obliged to make any restitution, and to retire with all their effects to the neighbouring British plantations.

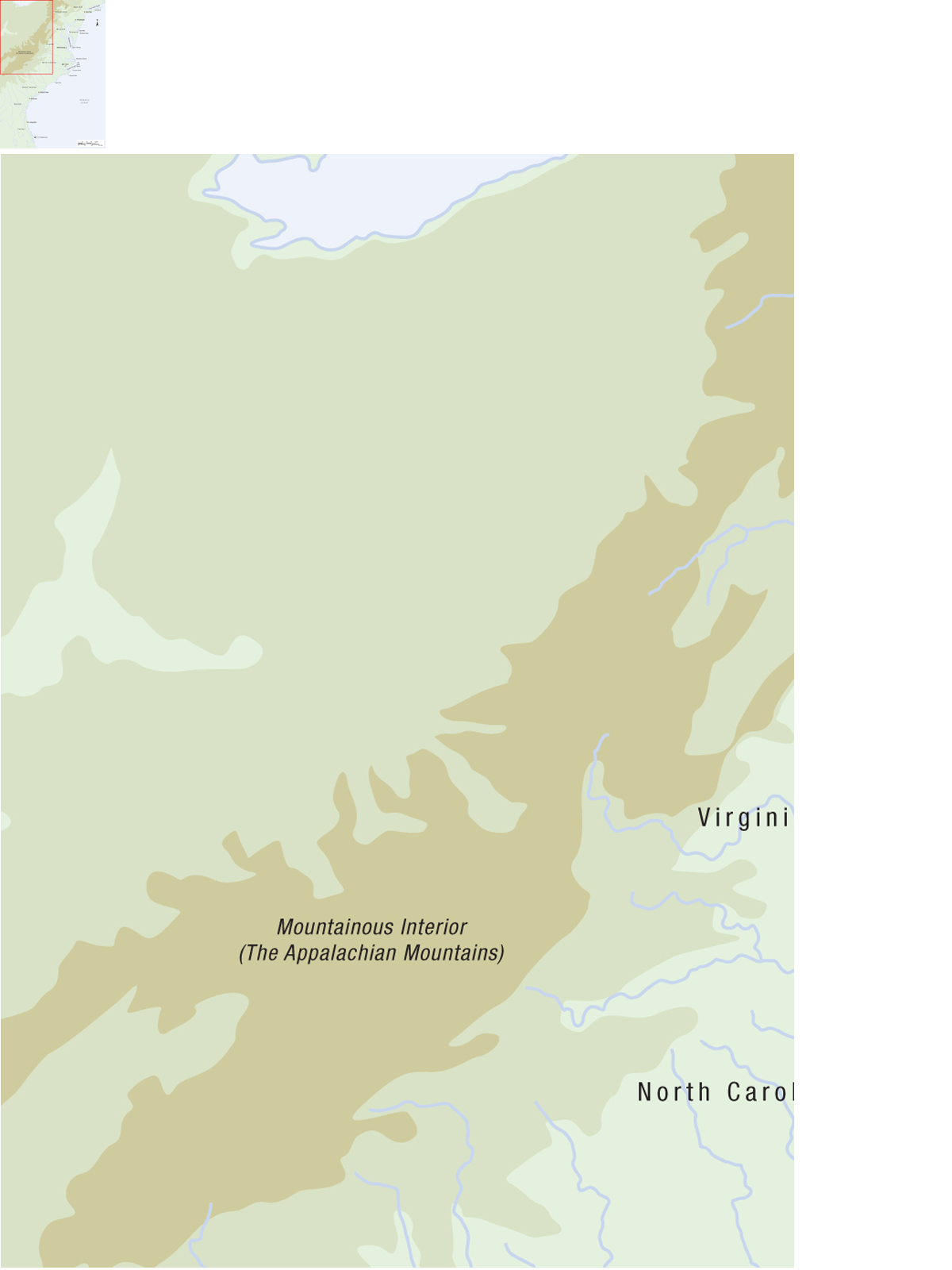

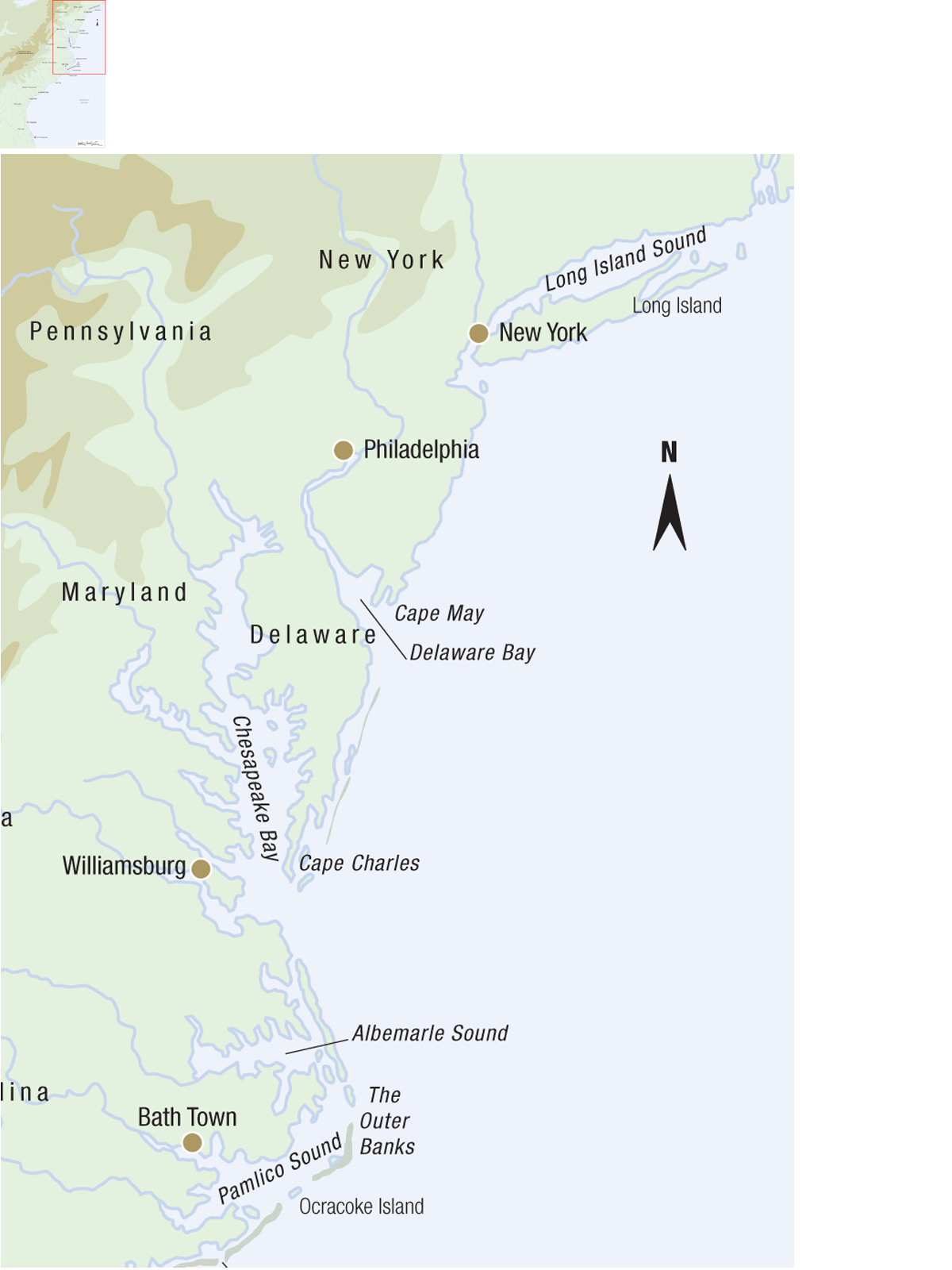

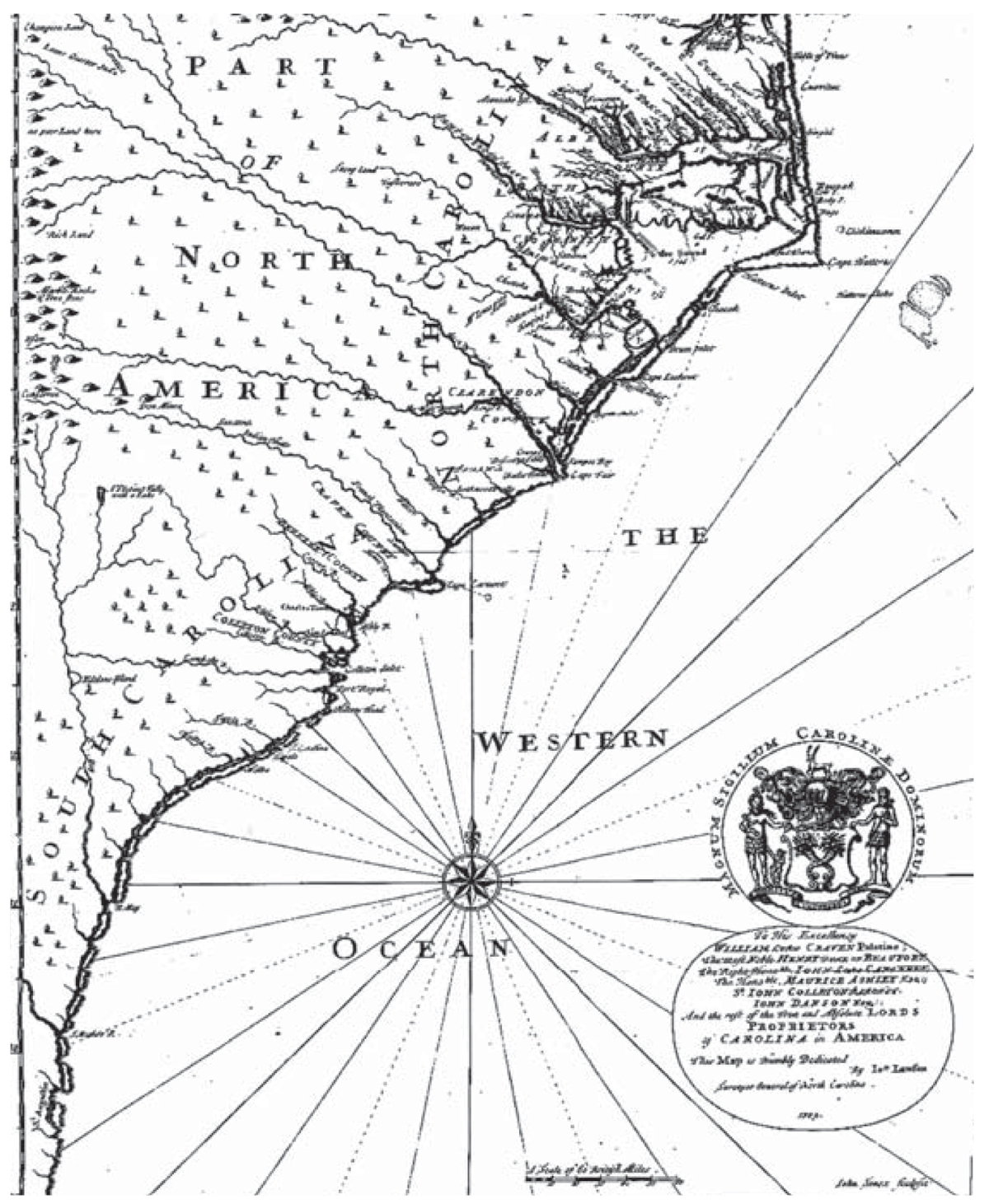

The Atlantic Seaboard of Colonial North America, as it appeared in 1718.

Although no portrait of Captain Brand survives, this depiction of a pirate-hunting contemporary, Captain Ogle, shows the uniform worn by a Royal Naval post captain during this period. It was Ogle who hunted down and killed the pirate Bartholomew ‘Black Bart’ Roberts.

Hornigold and Jennings pointed out that the notion of forming a pirate ‘commonwealth’ to oppose the might of the British authorities was completely impractical. The British could easily bring overwhelming force to bear to destroy the pirate den. Many were swayed by the idea of being able to walk away – there was no mention in the royal proclamation of paying restitution to the victims of piracy. Eventually the two leaders managed to convince around 150 pirates to surrender to the authorities when the opportunity presented itself. Others – the diehard pirates led by Charles Vane – remained adamant. They wanted no pardon, and would continue their piratical careers regardless of the decision of their fellows.

That council probably took place in February 1718. The following month the frigate HMS Phoenix arrived, and Captain Pearce went ashore under flag of truce to see whether the pirates were likely to accept the pardon or not. He confirmed there was no requirement to pay restitution, and was delighted that so many of the pirates were willing to ‘go straight’. After confirming there was no need for paying restitution a total of 209 pirates formally surrendered, and were issued with provisional pardons. While half of the pirates were still vacillating, Vane and his hardliners were becoming increasingly isolated.

Before he left in early April, Pearce told the assembled pirates that a British governor had been appointed, and would be arriving in a few months, backed up by a squadron of Royal Navy warships. While Vane and his supporters continued to attack ships, the rest of the New Providence pirates meekly awaited the arrival of British rule. In late July the new Bahamian governor, Woodes Rogers, duly arrived off New Providence, and was welcomed by the majority of the pirate community there. The exception was Charles Vane, who sailed a fire-ship in among the assembled British squadron, and made good his escape in the confusion, his sloop Ranger firing broadsides off to both sides as she went. While this was a spectacular exit it did little to alter the fact that New Providence was now closed to pirates. The Bahamas were now part of Britain’s overseas dominions.

When Captain Pearce’s Phoenix had left New Providence over three months earlier, Blackbeard was busy wreaking havoc among the logwood ships in the Gulf of Honduras. Like Vane he seemed to care little for the royal offer, and by late May his disregard for the scheme was demonstrated when he blockaded Charles Town. As all of these attacks had been carried out after the 5 January deadline given in the royal proclamation, Blackbeard was no longer eligible for a pardon. Instead he would be one of those diehard pirates who would be hunted down and made an example of. Amazingly, through luck or more probably forethought, the pirate approached the one colonial official who might be willing to overlook these recent crimes.

Blackbeard had captured enough British ships to learn all about the proclamation, and no doubt knew of the situation in the Bahamas. He realized New Providence was no longer open to him as a pirate base. Without one he would be unable to sell his plunder. Pirates needed shady merchants in order to prosper. The only solution seemed to be to surrender to the authorities, and to throw himself on the mercy of the governor of the North Carolina colony.

Blackbeard had targeted North Carolina for three good reasons. First, unlike neighbouring Virginia and South Carolina, the colony had no deep-water mercantile port, and so was less reliant on maritime trade. This meant the governor was less likely to be swayed by the influential merchants eager to seek justice against a notorious pirate. Second, the colony’s only port was a struggling backwater, and its traders were more likely to provide the pirates with the shadowy trading deals they wanted. Finally, the governor was widely regarded as a soft touch.

Governor Charles Eden had been appointed by Queen Anne in May 1713, and had set up residence near Bath Town. He was almost 45 in the summer of 1718, and had prospered during his five years in office. His 400-acre plantation lay on the opposite bank of Bath Creek from the small town, while he had another at Sandy Point in Chowan County, several miles to the north, close to the modern town of Edenton. He and Edward Teach first met in late June 1718. The governor had already met Stede Bonnet at Sandy Point, and now he travelled south to Bath Town to meet the pirate. He must have been apprehensive, as Bonnet had told him Blackbeard’s crew numbered over 300 men. He would surely have been mightily relieved when Blackbeard arrived with just two dozen pirates at his back.

The formalities were speedily dealt with. Blackbeard’s activities off Charles Town were conveniently ignored, and Eden’s deputy Tobias Knight dealt with all the paperwork. It may have been purely coincidental that Knight bought a substantial local estate around the time Blackbeard arrived in Bath Town, but after Governor Spotswood’s intervention allegations were made that Knight was in collusion with Teach. Certainly there was plenty of circumstantial evidence pointing to a profitable business arrangement between the pirate and the colonial official but nothing was proved.

For Governor Eden the surrender of Blackbeard and his men must have seemed like a real political coup. After all, he had rid the colonies of the most notorious pirate in American waters. He seemed completely penitent, and earnest in his desire to give up his piratical ways. Teach and his men were duly pardoned, and having turned their backs on piracy they swore to become honest merchants, working for the common good of the colony. Teach even set himself up in a house near Bath Town, and showed every appearance of honouring his word. That summer Eden must have been delighted.

In nearby Virginia Governor Spotswood was less enthusiastic. Like his fellow British administrator Governor Robert Johnson of the South Carolina colony, Spotswood saw the pardon as a sham. Blackbeard had flouted the terms imposed by the king by blockading Charles Town. Now it seemed as if he would get away with it. Spotswood was determined to hold Teach to account for his actions, but he had no authority in North Carolina, and so he had to bide his time, hoping that Blackbeard would make a wrong move. Sure enough, this was exactly what happened.

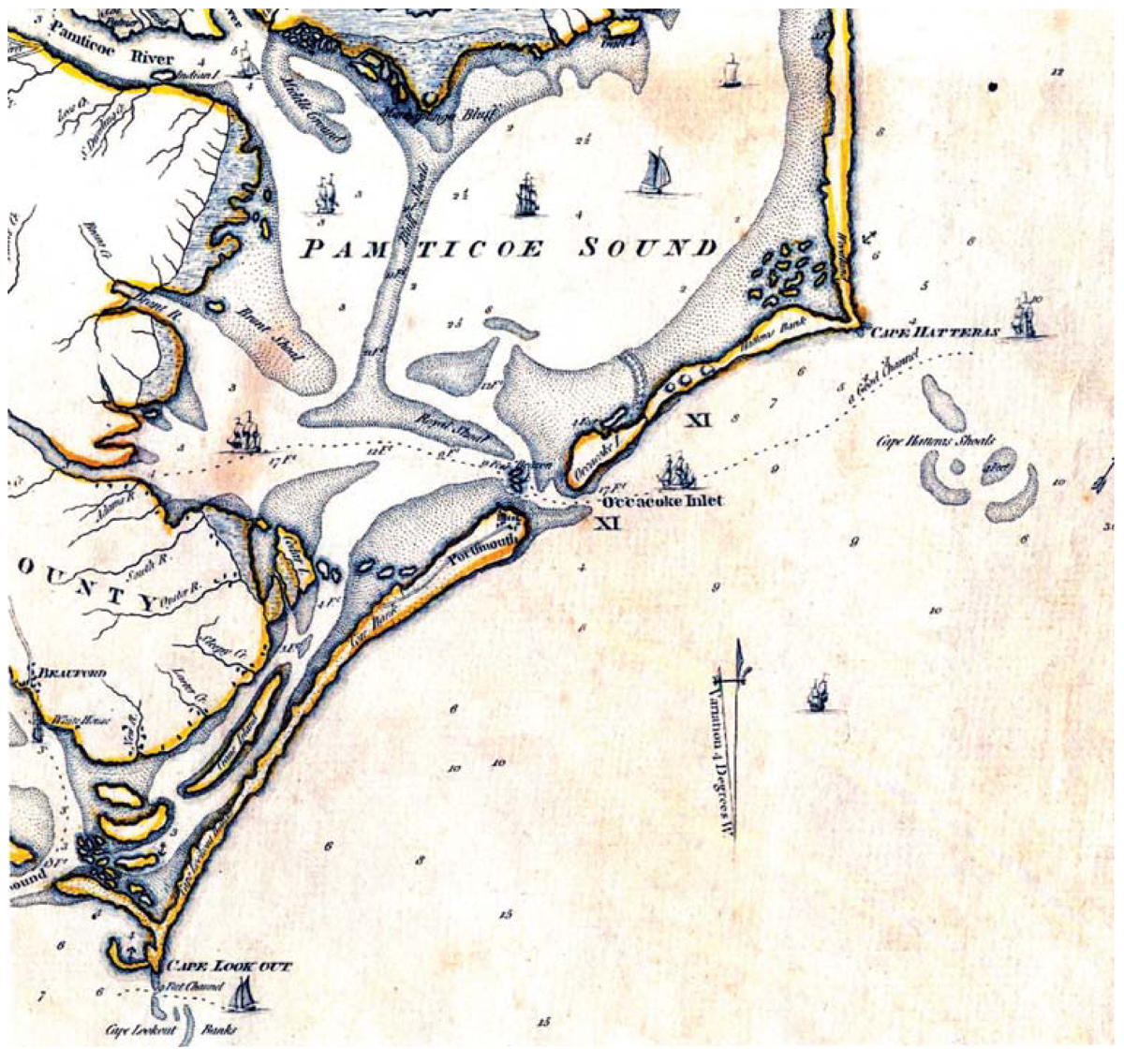

During July Teach began taking his sloop Adventure away on ‘fishing trips’ in Pamlico Sound, and during this time he used the western side of Ocracoke Island as an anchorage. Ocracoke was one of the string of barrier islands that formed the Outer Banks, lying between Pamlico Sound and the Atlantic Ocean. These waters were shallow and contained numerous sandbars, which seemed to move with every hurricane or winter storm. Then, in early August, Blackbeard returned to sea.

On 11 August Governor Keith of Pennsylvania issued a warrant for the arrest of Teach, and it seems the pirate was accused of harassing local trading ships in Delaware Bay. Blackbeard mightn’t have crossed the line into piracy yet, but intimidating traders to relinquish provisions was coming very close to it. He may well have attacked other ships – Captain Johnson suggests as much – but in late August he fell in with two French merchant ships, heading north from the Caribbean. He gave chase and captured them both. One vessel was fully laden, while the other was just carrying ballast. He moved the crew of the laden ship into her consort, and then let the second ship go. Blackbeard then sailed his prize to Ocracoke, where he spent most of September stripping her of her cargo and transferring it to a warehouse outside Bath Town rented to him for the purpose by Tobias Knight.

This was a risky venture, so he covered his tracks by claiming that he found the French ship abandoned on the high seas. According to Admiralty law this gave Teach salvage rights to the vessel. The trouble was, this fabrication needed to stand up in court. Fortunately Governor Eden either believed Teach, or turned a blind eye. As the Admiralty’s representative in North Carolina he convened an Admiralty Court, and Teach was granted salvage rights.

It may have helped Teach’s case that the local Admiralty representatives could claim a fifth of the cargo for themselves – a fee designed to offset administrative costs. Blackbeard duly delivered 80 barrels of sugar and cocoa to Eden and Knight. The rest of the cargo was sold in Bath Town, and the profits divided among Blackbeard’s crew. Meanwhile the remaining French ship sailed into Philadelphia and reported what had happened. It was clear to everyone outside North Carolina that Teach was nothing more than an unreformed pirate. Something clearly had to be done.

Governor Spotswood was incensed by the news, but what disturbed him even more was the report that Blackbeard had established a base on Ocracoke Island. This gave him a secure and remote base from which to operate, while still being close enough to Bath Town to sell his plunder to local merchants and unscrupulous local ship owners. Worse, there were reports that the diehard Captain Charles Vane had visited Ocracoke during his cruise off the Carolinas. Charles Vane’s sloop Ranger – the one that had fired on Governor Rogers two months before – put in to Ocracoke, and the two pirate crews held a week-long party.

To Spotswood this made Blackbeard doubly dangerous. It raised the possibility that Ocracoke would become a bustling pirate haven, attracting the very pirates who had refused the pardon. The Outer Banks lay close to the Virginia Capes, and so pirates based there could lie off the Virginia coast, plundering at will. If threatened they could easily evade any larger pursuers in the shallow waters of Pamlico Sound. In Pennsylvania Governor Keith fitted out two sloops for anti-piracy patrol duties in Delaware Bay. Governor Johnson of South Carolina did the same. By October these sloops were at sea, but no pirates were encountered.

In Williamsburg, capital of the Virginia colony, Governor Spotswood had another solution. As early as July he had issued a proclamation requiring all former pirates – pardoned or not – to register with the colony’s authorities. This was because Blackbeard’s former crewmen – the men stranded at Topsail Inlet – were starting to drift into American ports, including Virginia ones. Laws were passed to prevent them from congregating, and one of them, William Howard, was arrested. He was Teach’s former quartermaster from the Queen Anne’s Revenge, and although he would eventually walk free, no doubt he also told the authorities as much as he could about the pirate captain who had stranded him and sailed off with the plunder.

Alexander Spotswood, a man of action – he was a former colonel in the British Army – had in 1710 become the Lieutenant Governor of Virginia, deputy to Governor Hamilton, Earl of Orkney. However, Hamilton was an absentee governor, and so Spotswood ruled the colony in his stead. His many duties included overseeing the Virginia militia, and under his tutelage they became an effective and well-disciplined force. Faced with Blackbeard, Governor Spotswood had bided his time, but in October he made his move. He decided to put the Virginia militiamen to good use.

What he planned was effectively an invasion. North Carolina wasn’t a crown colony like Virginia, but it still proudly maintained its independence from its larger neighbours. A century and a half later, America was to tear itself apart over states’ rights. In order to deal with Blackbeard, Spotswood had to send his militiamen over the border, and – as he put it – ‘expurgate the nest of vipers’. This was all very well, but Blackbeard had a sloop, and could easily evade capture. That was why the attack had to be two-pronged – a march overland to capture the pirates in Bath Town, and a seaborne attack on Blackbeard’s sloop off Ocracoke.

Fortunately for Spotswood, two British warships were lying at anchor in the James River, some 30 miles downstream from Williamsburg. On Wednesday 13 November Captain Ellis Brand of the frigate HMS Pearl and Captain George Gordon of the smaller frigate HMS Lyme were summoned to Williamsburg by the governor, who met them in his partially completed palace. In theory neither captain was answerable to the colonial governor. They answered only to the Admiralty in London. Spotswood was answerable to the king through the Board of Trade. However, the frigates were there to protect the colony from attack by pirates, and both naval officers were willing to stretch their orders as far as they could, in order to deal with the threat posed by Blackbeard. With that problem sorted out, Spotswood and the two captains began planning the raid.

Despite the political furore it would cause, the planning of the land invasion was the easiest part. Captain Brand would lead a joint force of 100 Virginia militia and 100 armed sailors, and march them across country from the James River to Bath Town. When this force crossed the boundary line between the two colonies Spotswood’s authority would cease, and so Brand would have to deal with any diplomatic incidents that arose. He would also have to use his initiative when it came to rounding up the pirates in Bath Town, and confiscating any of their plunder.

This chart of Pamlico Sound dating from the 1770s shows the intricate nature of this inland waterway, filled with sandbars and shoals. Bath Town is in the top left corner, Topsail Inlet is in the bottom left, and Ocracoke Island lies to the north of Ocracoke Inlet, which is clearly marked in the centre of the chart.

The small sloop shown here is similar in size to the Ranger. The Jane was slightly larger, and probably resembled the one in the background, lying over on her starboard side being careened. Both sloops were fast, manoeuvrable and shallow-draughted.

Solid intelligence was hard to come by – Blackbeard and the bulk of his men could either be in Bath Town or off Ocracoke. However, it was thought most likely that they would be in the town. The expedition leaders had to be prepared for every eventuality. This was particularly true for the seaborne element, as it might be called upon to fight Blackbeard’s sloop the Adventure, chase it if it tried to escape, or round up the pirates if they were camped on the island. Both naval officers knew that the waters inside the Outer Banks were far too shallow for their frigates. Therefore they suggested that Spotswood hire two civilian sloops, which they could then crew with their own men.

This was duly done, and the small vessels Ranger and Jane were sent out to the frigates’ anchorage off Kecoughtan (now Hampton, Virginia). Lieutenant Robert Maynard, first lieutenant of the Pearl, was given command of the two craft, which were to be crewed by 32 men from the Pearl, who crewed the Jane, and 24 from the Lyme, who were sent into the Ranger. They were accompanied by one of the Lyme’s midshipmen, Mr Hyde, who would command the second sloop. Maynard himself took command of the slightly larger Jane. Finally, two local pilots were hired, one for each vessel, whose knowledge of the waters of Pamlico Sound would prove extremely useful. Counting Maynard himself, this meant the two sloops carried 60 men between them plus any civilian crew.

Maynard’s orders were to navigate their way through Ocracoke Inlet and capture any pirates they could find on the island. He would then cross the 50 miles of Pamlico Sound and enter the Pamlico River. Once in place he would blockade the river, hopefully trapping Blackbeard’s Adventure in Bath Creek. They would act as a floating reserve for Captain Brand’s force, who would sweep in from the landward side. If everything went according to plan the pirates would be caught in a trap. Naturally they would fight, and Maynard had to be ready to thwart any attempt by the pirates to escape by sea. However, as nobody knew exactly where Blackbeard was, Maynard had to rely on his initiative, and stand ready to do battle with the pirates wherever they might be. When fighting a dangerous and wily man like Blackbeard, nothing could be taken for granted.

In this mid-18th-century chart of the Carolina coast the geographical layout of the Outer Banks is readily apparent – a winding barrier of islands lying between the Atlantic Ocean and the shallow inshore waters of Pamlico Sound. Ocracoke lies at the end of the dotted NNE projection of the compass rose.