The whole operation had been carried out for one specific purpose. Governor Spotswood wanted to send a clear message to other would-be pirates that he and others like him were no longer prepared to offer pardons or forgive crimes. They were determined to drive pirates from American waters, and wanted the death of Blackbeard to signal that the days of these pirates were numbered. In fact the attack was only the first half of this exercise in statement-making. The second part revolved around the very public trial and execution of Blackbeard’s crew.

The captured pirates were gathered in Bath Town, and the majority of them then marched north under armed guard, accompanied by the men of Captain Brand’s column, and several wagon-loads of plunder. They left at the start of December, but bad weather delayed their progress. It was 18 December when they arrived in Williamsburg, and the pirates were finally incarcerated in the town gaol. Three days later Brand and his men returned to the Pearl.

A few days before the pirates started their long walk into captivity, Maynard had put to sea in his two sloops, and set a course for the James River. On 1 December the crew of the Pearl and the Lyme saw the Jane and Ranger approaching with their prize, with Blackbeard’s head still swinging from the Jane’s bowsprit. The sailors lined the decks to give Maynard and his men the heroes’ welcome they deserved. Maynard’s men cheered back.

After reporting to Captain Gordon, Maynard offloaded his own wounded, then continued on to Jamestown, carrying the pirates who were too badly wounded to make the journey on foot. They too were eventually deposited in the Williamsburg gaol. Similarly, many townspeople would have made the 8-mile journey to Jamestown, to welcome their naval heroes. More than a few also wanted to catch a glimpse of Blackbeard’s severed head.

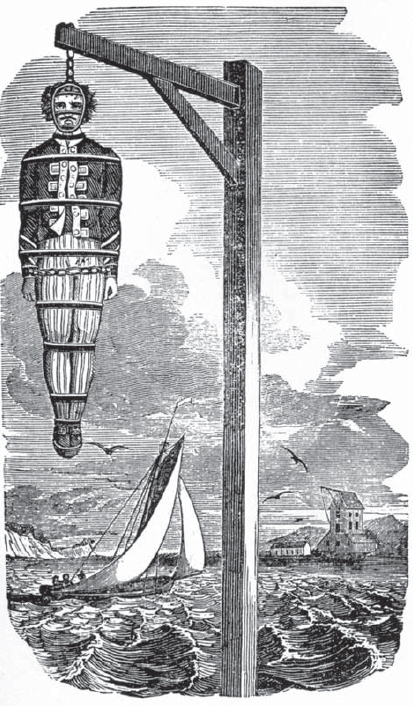

The execution of pirates was a public affair, attended by a large crowd, eager to watch the miscreant’s final moments. This was encouraged by the authorities, as it served to spread the message that there would be no clemency for convicted pirates.

As for his crew, they languished in prison for three months. There were 16 of them, including the unfortunate Samuel Odel, one of the two Carolina traders who were caught on board the pirate sloop when she was captured. Five pirates had secretly offered to testify against their fellow pirates in order to escape the gallows; four of these turncoats were former slaves, and the fifth was Blackbeard’s first mate, Israel Hands. His testimony would help to hang many of his former shipmates.

The trial began on 12 March 1719, and was held in the Capitol building in Williamsburg. The trial was conducted under Admiralty law, which meant that there wasn’t a jury. Spotswood presided, supported by the leading judiciaries in the colony. The charges were read out, and evidence was supplied that Blackbeard and the men on trial had continued their attacks after receiving their pardon. This of course was the crux of the case against them.

There was little chance of any leniency. For Spotswood the main aim of the trial was to discredit Governor Eden. By proving the pirates had seized the two French ships illegally he would expose Eden’s award of salvage rights to Teach as little more than a cover-up. The damning letter written by Tobias Knight merely added to the sense of a conspiracy between the pirates and the North Carolinian authorities. The Vice-Admiralty court came to a speedy verdict. All but one of the condemned men was found guilty of piracy and sentenced to death. This included all of the former slaves who had given testimony. The one prisoner who escaped the ultimate sentence was Samuel Odel, the sailor from Bath Town. He was set free with a warning about the dangers of falling into bad company.

The mass execution of the pirates took place a few days later, along the road leading into Jamestown. One after the other they were placed, standing, on the back of a cart, a noose was thrown over a tree at the side of the road, and the cart was wheeled away, leaving the condemned man hanging. One pirate escaped execution that day. At the last minute Israel Hands received a pardon. It was given because Blackbeard had shot him in the knee during an altercation, and so he was recovering in Bath Town when Blackbeard attacked the two French ships. Technically he was still covered by the pardon. In reality the last-minute pardon was a reward for turning informant.

The legal wrangling rumbled on for years, lasting until Governor Eden’s death in 1722. The first round was fought out in North Carolina itself. Edward Moseley accused Eden of profiting from piracy, but was arrested on the governor’s orders. In a trial orchestrated by Eden, Moseley was duly found guilty of ‘issuing seditious words’, fined, and barred from holding public office. He resumed his public duties after Eden’s death. Eden himself was cleared of any charges of wrongdoing by the colony’s Provincial Council, which as far as he was concerned was the end of the matter.

Alexander Spotswood had other plans. First he attacked Tobias Knight, accusing him of colluding with Blackbeard. Evidence included the testimony of the captured pirates, the letter found on board the Adventure, and the plunder found in Knight’s barn. In May 1719 he was brought to trial in a Vice-Admiralty court, but this was held in North Carolina, not Virginia, and Governor Eden presided. Hardly surprisingly, Knight was found not guilty. Knight died shortly afterwards, after suffering from a lingering illness which some unkindly said was brought about by guilt. As a result Spotswood’s case against Eden collapsed, and despite virulent protests to London no further enquiry into the affair was convened before Eden’s death. For his part Eden waged his own legal campaign, accusing Spotswood and Brand of a whole range of crimes, none of which was valid. The matter degenerated into a regular flurry of legal missives, which benefited nobody but the lawyers.

Spotswood was much less effective when it came to paying the pirate hunters. Maynard and his men were due a bounty of around £1,200 between them, but it took the Virginian clerks more than four years to pay what they owed. Even then they got it wrong – the reward was divided among the entire crew of the Pearl and the Lyme, including those who had taken no part in the expedition. That meant those who risked their lives in battle with Blackbeard only received a fraction of what they had been promised.

As for Maynard, he got into trouble for distributing the few coins and other trinkets found on the Adventure between his surviving crew. It was divided between the 47 survivors of the battle – the only reward for their services that many of these men ever received. When HMS Pearl returned to Britain in 1721 Maynard resigned his commission, and rejoined his family in Kent. However, he later rejoined the service, and ended his career with the rank of master and commander. He died in Great Mongeham in Kent in 1751, aged 67.

His superior Captain Brand shrugged off the writs issued by Governor Eden, and reached flag rank in the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739–48). Governor Spotswood survived the political fallout of the pirate-hunting raid, but he fell foul of his more domestic political opponents and was replaced as governor in 1722. He went back to London, where he married, but returned to Virginia shortly afterwards, and died in Maryland in 1740. Although Spotswood fell victim to political intrigue, the two men who carried out his raid both prospered in the years following the operation. This is hardly surprising, as its planning and execution demonstrated an impressive ability for leadership and motivation, as well as courage.

The North Carolina Maritime Museum in Beaufort, NC, contains a large number of artefacts recovered from the Queen Anne’s Revenge, which foundered just a few miles away from where the museum now stands. This display contains ordnance-related items recovered from Blackbeard’s 40-gun flagship.

After being executed, pirates’ bodies were often coated in tar to preserve them, and were then displayed in iron cages sited at the entrance to a harbour, to serve as a warning to others. Legend has it Blackbeard’s head was displayed in this manner at Newport News, Virginia.

All four of the organizers – Governor Spotswood, Captains Brand and Gordon and Lieutenant Maynard – had each contributed something to ensure the success of the operation. Spotswood had used his political abilities to undermine Governor Eden’s legal case, and to ensure the vital co-operation of Edward Moseley. Without his help Brand would have been hard-pressed to reach Bath Town without the pirates learning of his approach. His offer of a reward also helped to motivate the seamen, and ensured they had something worth fighting for apart from the honour of the service.

George Gordon provided the logistical support for the operation, and supervised the preparation of Maynard’s naval force. The provision of local pilots was a crucial factor in ensuring Maynard’s success, and his decision to leave the two sloops unarmed – he could easily have provided guns for them – was a difficult one to make. However, on the advice of the pilots it was decided that these would increase the displacement of the two sloops, and so make them less effective in the shallow waters of Pamlico Sound.

Ellis Brand was the man who first conceived this two-pronged attack, as he saw it as the only way to prevent the pirates from slipping through his net. His decision to use local sloops for the naval attack was largely due to their availability, but he could have carried out the assault another way, by sailing the two frigates to the mouth of Ocracoke Inlet, and then sending a cutting-out expedition in to attack Blackbeard’s ship. That was a sensible enough plan if Teach was at Ocracoke, but the intelligence reports Brand had at his disposal suggested the Adventure was 50 miles away to the west, in Bath Creek. That was too far for his men to travel comfortably in ship’s boats, so the sloops were really the only viable option available to him. Besides, by using local craft the pirates might question their identity long enough for Maynard to close the range.

During the land operation Brand took command of his joint force of Virginia militia and sailors, and drove them hard. The result was a fast advance across North Carolina: this speed reduced the possibility of word reaching the pirates, and of the local population offering resistance. To reduce this risk still further his co-operation with the North Carolina militiamen loyal to Edward Moseley was crucial in allaying the fears of the Carolinians, and preventing word of the column’s approach reaching Bath Town.

Then there was Robert Maynard. His cool leadership under fire proved crucial on that cold November morning. First of all, while he expected to encounter Blackbeard a day’s sail away across Pamlico Sound, his quick thinking allowed him to launch a well-conceived and thoroughly well-executed attack off Ocracoke, when the Adventure was sighted lying off the island. His decision to wait until dawn was crucial, too, as it gave his sober crewmen a slight edge over their adversaries. His decision to hide a large portion of his crew below decks proved critical when the boarding action started.

He realized that Teach had guns on his sloop, so it was imperative to close the distance as quickly as possible – hence the use of sails and sweeps. When the two sides came into contact with each other it was unfortunate that the Ranger was temporarily put out of action, but Maynard didn’t hesitate in closing with the enemy. Whatever the odds, he knew that boldness was the key to victory against these pirates. Then, when the fighting started he displayed his courage by singling out Blackbeard – a fearsome opponent – as he realized that without their leader, the pirates’ morale would crumble.

The raid can be held up as a perfect example of an anti-piracy operation. The combination of a land attack and a seaborne one was repeated in later similar anti-piracy missions carried out by the Royal Navy in West Africa and the Persian Gulf during the age of sail, and by the US Navy in the Caribbean. It was a bold plan, and it worked to perfection. This though, was largely down to the raw courage of a handful of British sailors, and the audacity of a plucky middle-aged lieutenant.