Mark Locklear outside his home in Prospect, North Carolina, in 2017. (Jordan Allott)

MARK LOCKLEAR DOESN’T FIT THE PROFILE of a Trump voter. A Native American and a registered Democrat who twice voted for Barack Obama for president, Locklear still has a deep admiration for Obama. He even keeps a framed photograph of the Obama family on a mantle in his home office. But what really makes Locklear defy the stereotype of a Trump voter—and most other kinds of voters too—is his ambivalence toward Trump, a president who has otherwise divided the nation into two distinct and seemingly irreconcilable factions. When Locklear talks about his feelings toward Trump, he often uses the metaphor of a pendulum. “There are days I sway in a positive direction, then he tweets stupidity, and my thought changes to negativity,” he once told me.

I first met Locklear at his home in Prospect, a “census designated place” located in the coastal plains region of southeastern North Carolina. A CDP is a statistical term the Census Bureau uses to describe small, unincorporated communities in rural areas, often places with more churches than traffic lights. Donald Trump performed very well in CDPs in 2016.

Mark Locklear outside his home in Prospect, North Carolina, in 2017. (Jordan Allott)

My first visit to Robeson County came a few weeks after Inauguration Day. A Bible-Belt county whose economy has been hollowed out by NAFTA and other free trade agreements, Robeson has one of the state’s highest poverty rates and a murder rate four times the national average.1, 2 It’s also America’s most racially diverse rural county: roughly 38 percent Native American, 33 percent white, and 25 percent black.3 It is also historically Democratic—very Democratic. Until recently, registered Democrats outnumbered registered Republicans 7 to 1.4

Like Mark Locklear, Robeson County as a whole voted for Donald Trump in 2016 after twice going for Obama.5, 6 Native Americans from the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina proved to be the difference makers.

Mark had invited me out to his house in Prospect, where more than 90 percent of residents are Lumbee and 73 percent of voters cast their ballots for Trump.7 8

Locklear met me in his driveway. The first thing I noticed about Mark was his broad shoulders, thick graying mustache, and imposing presence. The second thing I noticed was his deliberate manner and the thoughtfulness with which he answered my questions. Locklear, 54, has lived in Prospect his entire life. As we stood in his front yard, he pointed out the place where he had attended grade school and where he goes to church, along the unpaved Missouri Road, named after his great-grandmother.

Locklear has been in law enforcement his entire life. He started as a jailer in the sheriff’s department before working his way up to major chief general of detectives. Now he’s a criminal defense investigator. Locklear wore an orange long-sleeved shirt with the image of an American Indian in headdress and the words, “Lumbee Native Blood” inscribed in large black letters. Despite Mark’s tribal affiliation, he rejects the tribalism that defines modern politics. Mark is a Democratic precinct captain who once ran for county sheriff as a Democrat. But he had recently worked to elect a conservative Republican to the state senate. Then there was his swing from Obama to Trump.

Locklear was taken with Obama’s charisma and his promise to fight for the middle class. Mark was a big Michelle Obama fan, too, and felt that the Obamas were ideal representatives of the country. But Locklear’s confidence in Obama’s governance waned somewhat, first when Obama withdrew US troops from Iraq, and then when Obamacare caused his health insurance premiums to skyrocket, along with those of millions of other Americans. So in 2016, Locklear joined his county, his state, and his country in turning from Obama to Trump.

Locklear liked that Trump was not a politician, that he promised to “drain the swamp” in Washington, DC, and that he pledged to repeal and replace Obama’s signature health care law. But during my first meeting with Mark, it was clear he wasn’t fully sold on the new president. “Has Donald Trump earned the people’s respect yet?” he asked. “I don’t think so. He hasn’t earned mine.” As he spoke, sitting on a couch in his home office, the Obama family portrait was on the mantle just over his shoulder.

“But with that being said, I am willing to give him a chance.”

***

Robeson County is a hard place to figure out socially and culturally. It’s a rural county that has a lot of the problems endemic to inner cities, with a toxic brew of poverty, racial segregation, drugs, and violent crime. Politically, it’s even harder to understand. Phillip Stephens, who heads the county’s Republican Party, emailed me before my visit, suggesting that the racial complexity and political shifts made the place a complicated case study. “I was once told that if you wanted an undergrad degree in politics, go to Yale,” he wrote. “For a prestigious graduate degree in politics, Harvard would be best. But to get a PhD in political science, you have to come to Robeson. Good luck figuring it out.”

Local connector Bo Biggs helped me set up interviews with people across the county. On my second evening there, I huddled with Biggs, Stephens, and a group of other local Republicans at Candy-Sue’s Café in Lumberton, the county seat. Biggs said that during the 2016 campaign, the first indication that Trump would do well in the county was the overwhelming number of people who requested Trump campaign yard signs. So many people asked for them that the local Republican Party ran out, prompting people to take matters into their own hands.

It is not uncommon for people to steal campaign signs from other people’s lawns in the heat of an election campaign. But normally people confiscate the signs of candidates they oppose. In Robeson County, Biggs said, as Trump gained traction, “people were stealing (Trump) signs to put them in their own yard.”

Trump won North Carolina and its 15 electoral votes by carrying seven rural counties that had voted for Barack Obama in 2012, including Robeson.9 An easy explanation of Robeson County’s transition from blue to red focuses on economic stagnation and cultural despair. But from a slightly different vantage point, Trump’s 5-point victory had more to do with his ability to tap into the same desire for hope and change as Obama had shown in his 18-point victory four years earlier. At the time of Trump’s victory, registered Democrats outnumbered registered Republicans in Robeson two to one. Until 2016, the county hadn’t voted for a Republican for president since 1972, or for a Republican state senator since Reconstruction. Both of those things changed in 2016.10

But the first thing I noticed upon entering Robeson County wasn’t its racial diversity or its changing politics, but rather its pervasive poverty. It was there in the abandoned manufacturing plants I saw along Interstate 95 as I approached Lumberton. And it was also there in the trash-lined streets and abandoned homes of south Lumberton—remnants of Hurricane Matthew, which had laid waste to the city six months earlier.

Robeson County’s median household income of $33,000 is half the national average.11 A quarter of residents live below the poverty line, and two-thirds are classified as low-income, making it one of the most impoverished counties in the nation. Ask anyone in Robeson County about the causes of this poverty and sooner or later—probably sooner—they’ll start talking about the North American Free Trade Agreement, any mention of which is usually accompanied by some form of the verb devastate.

“When NAFTA came about in the 1990s it devastated the local economy,” said Stephens. “All the textile plants moved to other countries. You’re talking about one of the poorest counties in the nation that was devastated. You can’t find anybody here that doesn’t know someone who lost their job from NAFTA.”

Remnants of Hurricane Matthew were still apparent six months after it struck Lumberton. (Jordan Allott)

“It is a very economically deprived area. They’ve really been hit,” said Robert Pittinger, who represented Robeson County in the US Congress at the time. “The loss of textiles, the loss of manufacturing. It already was a poor county, but (NAFTA) really devastated it.”

Signed into law in 1994, NAFTA toppled trade barriers between Mexico, Canada, and the United States. Subsequent trade deals did the same between the US and other countries. Thirty-two Robeson County industrial plants closed over the following decade, displacing thousands of workers, many in the textile industry. First, Sara Lee Knit Products closed three plants and fired 1,275 workers. Alamac Knit Fabrics laid off 750 people. Then came the big one: Converse, the iconic shoemaker. Once the county’s largest private employer with 2,400 employees, it shuttered operations in 2001.12 One researcher estimated that Robeson County lost as many as 10,000 jobs due to NAFTA—more than any other rural county in America. That’s out of a total population of just 134,000.13

Tech, industrial, and other professional jobs are scarce now. More residents find work in the hotel, food, and retail industries that serve travelers on Interstate 95, which bisects the county, than in manufacturing. “If it weren’t for the interstate, we might not be sitting where we are today,” said Stephens.

But Interstate 95 is also a strategic hub of opportunity for criminals and drug and human traffickers, making their way along the Atlantic coast between Miami and Boston. They often stop off in Lumberton, partly explaining the county’s worst-in-the-state crime rate.

Against this backdrop, it is easy to understand how Trump’s abject hostility toward NAFTA made him such an attractive candidate. When Trump pledged to create jobs, protect workers, and renegotiate NAFTA, which he assailed as one of “the worst trade deals” in history, many free-trade conservatives rolled their eyes.14 But in Robeson County, it won him an enthusiastic following.

“When Donald Trump made this statement, it was very profound,” Stephens said at my meeting with local Republican officials. “He says, ‘You guys passed NAFTA, and that’s supposed to be free trade, but it’s not free trade if it’s only free one-way.’ That one statement resonated with citizens here regardless of their ideology, regardless of their party affiliation, because that transcended ideology. This was economy, which was even more important.”

Phillip Stephens speaks at a meeting with Republican leaders in Lumberton, North Carolina, in 2017. (Jordan Allott)

With his willingness to shatter what had been a bipartisan consensus on trade, Trump inspired hope among Robeson County residents not unlike what Obama had inspired in 2008. Obama, it should be remembered, actually pledged in 2008 to renegotiate NAFTA. He never did keep this promise, and as his advisors reassured Canadian officials at the time, he never really intended to.15 But this was just a minor issue in his campaign—a day’s worth of messaging, quickly forgotten.

In places like Robeson, what made Obama attractive was his promise to bring about an era of post-partisan politics and a post-racial society. But Trump, who seemed incapable of shutting up regarding NAFTA, emphasized something more meaningful for Robeson’s residents—economic renewal.

“You mostly hear the word ‘hope’ associated with President Obama’s campaign—I mean, it was a central tenet in his message,” said Emily Neff-Sharum, who heads the political science department at the University of North Carolina at Pembroke in the western part of the county. She added:

But when you think about the Trump slogan of “Make America Great Again,” I think that really resonated with this area, (which) has really struggled since the closing of factories after NAFTA went into effect. For a lot of the country, most people don’t really think about NAFTA. But those free-trade agreements, when they started becoming a centerpiece of debate, absolutely hit really close to home in this area.

It may seem counterintuitive, but hope and change were words I heard over and over again in 2017 while traveling through Robeson County and other Obama-Trump counties across the country. When you look at places that supported both Obama and Trump, you start to realize that Obama and Trump had a lot in common.

I asked everyone I interviewed in counties Trump won to try to sum up in just one word why they believed he won. There were many offerings, but hope and change were the two words I heard most often. And I heard those words from Trump supporters and critics alike.

The media covered Trump as a figure who went about sowing fear and pessimism. After all, he had published a campaign book called Crippled America.16 He warned that violent criminals were crossing the borders and that complete idiots had negotiated America’s trade deals. But to many of his voters, Trump the pessimist had paradoxically cultivated a sense of hope. This was in part because he seemed like a lone voice of reason, questioning a status quo to which everyone else was inexplicably and constantly paying homage.

Imagine for a moment that everyone in Washington had been praising cancer—the disease—for decades. They all said it was a godsend, the best thing ever. Then, after millions had died of it over the decades, one politician finally came along promising to fight cancer! In Robeson County, where NAFTA is held up as the explanation for so much devastation, this is exactly how Trump came across. He openly disparaged the trade deals that everyone believed had devastated areas like Robeson—rural areas with large manufacturing bases.

By rupturing the bipartisan consensus on free trade, Trump demonstrated that he wasn’t listening to the Washington politicians, K Street lobbyists, and think-tank ideologues who shape America’s trade policy.

Trump’s unorthodox thinking on trade was evidence that he was listening to those who had been most harmed by free trade agreements. It showed that he acknowledged their existence, their work, and their plight, and that he didn’t much care what politicians had done before. He was going a new way—his own way.

***

The conventional wisdom during the 2016 presidential campaign held that Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric would alienate millions of minority voters. They would turn out in massive numbers on election day to deliver the presidency to Hillary Clinton. The thing about the conventional wisdom, though, is that it can be profoundly unwise sometimes. That’s especially true with a candidate as unconventional as Trump.

Trump didn’t perform very well overall with nonwhite voters. But he won a larger share of them than Mitt Romney had in 2012. And in some places, minority voters actually helped deliver victory to Trump.

The Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina is the largest Indian Tribe east of the Mississippi River. Robeson County’s roughly 50,000 Lumbee Indians make up a plurality of its electorate.17 Pembroke is the tribe’s political and cultural center. It’s home to the University of North Carolina-Pembroke, a historically Native American university. That’s where I met up with Jarrod Lowery one rainy afternoon in March 2017.

“The reason Robeson County voted Republican is the Native American population voted Republican,” Lowery, a representative on the Lumbee Tribal Council, said. He said that Lumbees started considering the Republican Party when Republican gubernatorial candidate James Holshouser championed the “Save Old Main” movement in the early 1970s. The Old Main, UNC-Pembroke’s oldest and grandest building, was slated for destruction. After the building’s destruction in a 1973 fire, the newly elected Holshouser had stood on the steps of the charred building and promised to rebuild it. It was restored in 1979.

“When Governor Holshouser said, ‘We’re going to rebuild Old Main,’ there were a lot of elders at the time and people in the community who said it was the first time they considered voting for a Republican,” Lowery said.

Lowery explained that Republicans’ social conservatism and emphasis on law and order also resonate with the Lumbee, whose values focus on faith, family, and traditional mores. “Our people have always been fiscally conservative because we believe in working hard and saving our money. But social issues are what are really big.” The Lumbee don’t mind helping those in need, Lowery said, “but when the Democratic Party in America took that hard left on social issues, Lumbee people started backing up.”

The media tend to focus on the economy as the main factor driving voting patterns, particularly in former industrial centers like Robeson County. But social issues play at least as big a role. This reality was hammered home for me repeatedly as I conducted my research in Robeson County. John McNeil, who led the Robeson County Democratic Party in 2016, also identified social issues as pivotal to Trump’s success. McNeil said he was expecting Hillary Clinton to win the county with 60 percent or more of the vote. The reason she didn’t, he later realized, was the level of involvement from Christian pastors during the campaign.

“The churches were very, very active in the election, and of course the big issue was abortion. That and gay marriage were the problems,” McNeil said, pointing to the 86 percent of Robeson County voters had supported the state’s 2012 constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage in North Carolina, the highest share any of the state’s 100 counties.18

On election day 2016, only 10 of Robeson County’s 39 precincts voted for Clinton, and those that did were in heavily black areas. Sixty-six percent of voters in Maxton, for instance, in the western corner of the county, voted for Clinton, which is slightly higher than the 64 percent of its residents who are black.19 Trump got about the same share of the vote in a neighboring precinct that’s 67 percent Lumbee Indian. And Prospect, “the oldest Lumbee community, which is 96 percent Lumbee, voted 73 percent for Trump,” Lowery said.

The most important issue for the Lumbee is official recognition by the federal government. This would require a federal law, and it would allow hundreds of millions of dollars to flow into the county. But the Lumbee are also looking for a more basic kind of recognition—one that comes from the human need to feel listened to. “A lot of time throughout the country, we are forgotten,” Lowery said. “People go down the list of minorities, but nobody ever mentions Native Americans, Native Alaskans, or Native Hawaiians. So when you have a politician who points at you and takes an interest in you, you’re like, ‘Wow, somebody’s finally paying attention to me.’” Lowery felt that Trump was one politician who might finally pay attention to them.

“Lumbees don’t trust the government,” he said. “And when you have a guy who comes in who looks like he’s going to bust up the system, who admits there’s corruption here and there’s corruption there, we say, ‘This guy’s saying that same things I’ve been saying.’”

Lowery continued, “There (were) a lot of individuals I spoke to who would say, ‘Well, this guy isn’t liked by Democrats. He isn’t liked by Republicans. Maybe this is the guy that is actually standing for me.’”

Later, over barbeque sandwiches at Papa Bill’s restaurant outside Pembroke, Lowery continued on the importance of feeling listened to. “With us, what matters is that you listen to us,” he said. “That people say, ‘Those Lumbee, they’re important, they’re as important as people in Silicon Valley, as important as New York City; they’re important.’ That’s all we want.”

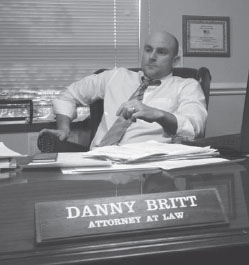

Another politician who listened was Danny Britt. In 2016, Britt became the first Republican since Reconstruction to win the state’s 13th-district senate seat, earning 55 percent of the vote. He won in large part because of strong support from the Lumbee community.20 “Senator Britt come to my home community of Prospect several times asking for our vote,” Lowery said. “And when you have been told your whole life, ‘You don’t vote for Republicans,’ and you have (a Republican) that comes to your door and says, ‘Hey, can I have your vote?’ That starts opening you up a little more.”

Another thing that opens people up is being present for them in their time of need.

When Hurricane Matthew struck a month before the election in 2016, it laid waste to many communities along the Atlantic Coast. Robeson County, which is an hour’s drive inland, was not spared. But as residents hunkered down, Danny Britt stood up and got to work. “The whole town was thrown into absolute chaos real quick,” Britt told me at his law office in Lumberton. “Roads were shut down, and there was no power. Bridges were out all over the place.” In the ensuing deluge, which reached nearly twenty-three feet above flood stage on the Lumber River that runs through downtown Lumberton, Britt summoned his “go-fix-it” personality and the skills he’d acquired in relief efforts as a National Guardsman and did what he could to help.

North Carolina State Sen. Danny Britt in his law office in 2017. (Jordan Allott)

“I’m a good ol’ boy,” he said. “So, when stuff like that happens—anything bad happens—I kind of jump to it.” He started by helping a friend’s aunt who had retreated to the roof of her house. He then hooked up a boat trailer to his truck, delivered food and supplies to those in distress, and helped rescue stranded neighbors.

Britt was in the middle of a closely contested race for the county’s state senate seat. He didn’t go out of his way to broadcast who he was during the storm. “He never wore a campaign shirt. He never did an interview,” said Mark Locklear, who works with Britt as a criminal investigator. “He was just busting his ass to help people, and it was being noticed. People saw this. People began to talk about it—the passion that he had to help others.”

When calamity strikes, people pay attention to who shows up to help and who doesn’t. In this case, one of the people who showed up to help was a local attorney who happened to be the Republican state senate candidate. “He was going door-to-door helping everyone he could, you know, helping people get out of their houses, doing whatever he could,” said Matt Walker, whom I met at Candy-Sue’s. “He was rolling up his sleeves and getting dirty, and you just didn’t really see that from the Democrats.”

Another person who showed up—or at least whose campaign showed up—was Donald Trump. Matt Walker’s mother, Susan, part-owner of Candy-Sue’s, recalled how Trump’s daughter-in-law Lara Trump delivered food and other provisions in a Trump campaign bus in the days after the flood.

“The thing about President Trump, when the hurricane came, there were people in the streets,” Susan said. “There were homeless people everywhere.”

We had shelters. One day, I went down to the Bill Sap Center, and I was taking some food down there, and there was President Trump’s big old bus, and they were delivering waters and stuff, and supplies. I think it was his daughter-in-law that was there. She actually came down. I think it had a big effect on a lot of people when they saw what he had sent to our county. He was trying to help us when we needed help.

“That swayed a lot of people,” Tiffany Powers, a local attorney and Democratic precinct captain, said. “Hillary didn’t come down here, and that’s where she lost.” When I asked Powers for one word on why Trump won Robeson County, she quickly offered two: “Hurricane Matthew.”

Tiffany Powers and Daniel Allott in downtown Lumberton in 2017. (Jordan Allott)

***

Danny Earl Britt Jr. was born in Robeson County in 1979. After college at Appalachian State University, where he walked on to the football team, and law school at Oklahoma State, he worked at a law firm in another part of North Carolina. But he soon found his way back to Robeson County, working first as a prosecutor in the district attorney’s office and then as a defense attorney. He also spent time as a military prosecutor in the Judge Advocate General Corps in Iraq. Britt’s senate campaign focused on jobs and education, both of which were sorely lacking in the county. Britt said raising graduation rates is vital to attracting good jobs. One-quarter of adults in Robeson County have not finished high school, and only 13 percent of adults there have a college degree.21

In 2015, the Robeson County School District spent $525 per student, second to last among the state’s 100 counties. In Chapel Hill-Carrboro, a district to the north, the per-student average is nearly eight times that.22 Britt won his seat less because of the policy positions he took and more because of the commitment he showed to helping his community. He wants his children to have the option of living in Robeson County, so he thinks about its future. Britt is a big believer in the power of showing up and getting to know voters, including those who historically have not voted Republican.

Locklear said he initially had “a lot of concerns” about Britt’s candidacy, specifically because he was running as a Republican. “We had never supported a Republican candidate, to my knowledge,” he said of the Lumbee. Locklear drove Britt around Lumbee communities in his pickup and found that the simple act of introducing him was often enough to win votes. Britt also displayed energy. “Danny was a hustler,” said Locklear. “As a Republican, I still thought we had an uphill battle, but he’s a very likable and approachable person that has robust energy.”

Britt visited every precinct in his district. “We had these little corner functions or went to the cafe, stopped at the station and went to the barbershop, or went and had a collard sandwich,” Locklear said. “He got out and done these on a daily basis. That resonated with people.”

In Lumbee-dominated Prospect, Locklear estimated that 80 percent of registered voters there are Democratic. Britt won them five-to-three.

During the storm, Britt recalled people saying, “’Man, this dude doesn’t sleep.’ You know. I didn’t sleep much. Less now. But I think … a lot of folks just really like the idea of somebody that gets out and does rather than says.”

***

Of all the interesting statistics to emerge from the 2016 election, one of the most compelling was this: Donald Trump won 76 percent of the 493 US counties with a Cracker Barrel Old Country Store; he won just 22 percent of the 184 counties with a Whole Foods Market.

That 54-percent gap is the largest ever recorded, according to the Cook Political Report.23 It has widened in every election since 1992, when it was just 19 points. The gap was smaller even in the 2008 cycle, when Barack Obama cluelessly asked an Iowa audience, “Anybody gone into Whole Foods lately and see what they charge for arugula?”24

Trump’s performance in these counties was a token of the increasing cultural divide between red counties and blue counties. But it’s more than that, as I discovered during my trip to Robeson County. The county’s only Cracker Barrel is just off Highway 95 in Lumberton. One evening I decided to stop in for dinner. The Lumberton Visitors’ Bureau, the Greater Hope International Church, and the Lion’s Den Adult Boutique are on the same road.

Cracker Barrel’s 630 restaurants are located in forty-two states, but most are on the East Coast, in the Rust Belt, and in the South. It boasts meals that are “homestyle” and “made from scratch.” I tried the meatloaf, biscuit, coleslaw, and potato casserole, and then interviewed Evita, my nineteen-year-old waitress. She said she’d worked at the Lumberton Cracker Barrel for two years and enjoyed it. It’s a friendly place and she gets along with her coworkers. “It’s like a dysfunctional family,” she quipped.

When I told her about the Trump-Cracker Barrel statistic, she didn’t seem surprised. “Gun rights, older folks with older ways,” she said by way of explaining why these places were attracted to Trump’s message. “They’re from a generation that stresses an older American way.” Evita was right: nostalgia for “an older American way” is evident in every tool, sign, and photograph that adorns the walls of Cracker Barrel restaurants. It was also the subtext of Donald Trump’s campaign pledge to “Make America great again.”

Alexis, a Lumbee waitress in her thirties, approached me to tell her story. A Robeson County native, Alexis had worked at Cracker Barrel seven years and was now a manager. Alexis pointed to high Obamacare premiums and Trump’s “generosity” as the reasons why he won in the county, and why she had voted for him. Asked for specifics about the latter, she offered that Trump had given up his business and pledged to take no salary in the White House. “People appreciate that,” she said, adding that she thought Trump was doing a great job.

Overhearing my conversation with Alexis, Danny, the store’s head manager, walked over and declared emphatically that he was a Trump supporter. At this point, almost all of the other customers had left, and most of the staff was getting ready to leave for the night. Danny talked as we headed to the doors, through the Old Country Store that sells everything from fried apples to baby clothes. He said I’d be welcome to visit again should I ever return to Lumberton.

The feeling of being welcome is important to everyone, but perhaps especially to those in the Rust Belt, the South, and other places where many people feel ignored or disparaged by a distant elite. They feel excluded from the popular culture and alienated from the rich enclaves around Washington, where too many of society’s rules are made. They make a living with their hands or by driving things from one place to another. The people they feel ignore them don’t do that.

Comfort food is what people want in places where comforts are hard to come by, places such as Robeson County, where nearly a third of the population lives below the poverty line—where church attendance is sagging, where schools are woefully inadequate, where families are fracturing, and where people are losing their lives to drug addiction and violent crime. In these places, nostalgia for what Evita called “an older American way” is what people yearn for. That’s what they believed Trump offered them.

***

On subsequent visits to Robeson County, I found more evidence that the county was trending Republican. On a visit in the spring of 2018, I attended the Robeson County Republican Party convention at the Lumberton Lions Club.

Phillip Stephens announced that the local party was just sixty-one voters shy of 10,000 registered Republicans in the county. Stephens later explained that North Carolina’s closed primary system means most voters register as Democrats in order to vote in the primaries. Stephens, a former Democrat, said his strategy is to encourage local Democrats to switch to “unaffiliated” as a half-step to becoming a Republican.

After the meeting, I asked Stephens how Trump’s support was holding up in the county more than a year into his term. “We have not seen Trump’s support die down at all,” he said. “But we’ve seen from Trump supporters anger at the media, who distort what he says and darken everything he does.”

Later in 2018, Danny Britt improved on his 2016 election performance, winning reelection with 63 percent of the vote, again pitching in a month before the election when the area was devastated by a hurricane and flooding.25

Then came a special election in September 2019 for North Carolina’s ninth congressional district. Ballot fraud had marred the initial election nearly a year earlier, which the Republican candidate won by a slim margin, and so a new election was called. Republican Dan Bishop was predicted to win the district, which had been in Republican hands since 1963. He did win, but many analysts failed to grasp why. Lowery dissected precinct-level vote totals in an op-ed for The Hill newspaper (where I am an opinion editor), and made a convincing argument that Lumbee voters played a crucial role.26

“Many Lumbee feel that the national Democratic Party has simply left them behind as they’ve embraced more extreme social and economic positions,” he wrote. “We’re tired of Democratic policies that insult our faith and fail us economically. Democrats’ opposition to voter identification laws, support for abortion-on-demand and attacks on religious liberty have alienated many Lumbee.” Lumbee, Lowery continued, “hold strong to the values of family and hard work. And at the moment, the Republican Party does a better job of respecting those values.”

As for Mark Locklear, I contacted him periodically over the next three years, asking for his reaction to developments in Trump’s presidency or to pick his brain about local political affairs. Whenever I visited Robeson County, Locklear would invite me to drop by his home office for a chat. I’d always check without saying anything to see if the Obama family photo was still perched on his mantle, and it always was.

State Sen. Danny Britt, Daniel Allott, Jarrod Lowery, and Lumberton City Councilman Chris Howard during relief efforts in the wake of Hurricane Florence in 2018. (Author’s personal collection)

Mark was always welcoming, even when I showed up at inconvenient times. One day in 2018, I arrived just after he’d discovered that his ATV had been stolen. He graciously chatted with me as he waited for the police to arrive.

When the media lambasted Trump for his response to Hurricane Harvey in 2017, Locklear gave him an A+ grade. “I don’t doubt his passion to help the American people,” he wrote to me. Locklear grew frustrated at the media’s treatment of the new president. “I do wish the media—and I am a CNN freak; I love Anderson Cooper—but I have been swayed to watch now more Fox because of CNN’s coverage. …I say, ‘Back off, give the man a chance.’”

Locklear also didn’t hesitate to criticize Trump when he felt it was warranted. “Mr. President, please stop the negative tweets,” Locklear wrote back to me when I asked what advice he would give Trump at the six-month mark of his presidency. At that point, he gave the president an “A” on policy but lowered his overall grade to a “C” because of Trump’s injudicious use of Twitter.

Mark Locklear in his home office in Prospect, North Carolina, in 2017. (Jordan Allott)

“Oh, my. ‘Shit hole countries’? Dan, now I am concerned.” That was the brief email message I received from Locklear six months later, after Trump’s casual use of that term to describe several less-developed countries. A few months later, he wrote to say that the child separation policy at the border “really pissed me off.”

When I met with Mark in the spring of 2018, he again talked about the pendulum, “I can tell you it has certainly swung in a positive direction. Several things have me thinking that.” He knew to the dollar how much the tax cut was helping him—$18 on net every two weeks for his wife’s job. And he gets 10 cents more per mile for work from the county. All of that equals about $600 a year. That’s enough to pay the water bill every month, he said. It reminded me of the previous year, when he had recited to the dollar how much Obamacare was costing him and his family, which had dampened his enthusiasm for Obama.

Locklear said he had grown weary of Trump’s cyber saber-rattling with North Korean dictator Kim Jong Un. “I was concerned with the ‘Rocket Man’ comments,” Locklear said. “Is he inciting a war here?” he had asked himself at the time. He had a very personal reason to be concerned. A year earlier, his son, Ethan, had joined the Marines. Ethan is an ammunition technician in the Marine reserves. “When he told us he was going into the Marines, he said he wanted the ultimate challenge,” Mark said. “He reported on July 10. I cried many a tear. I sent letters every day for fourteen weeks to Marine basic training. He is at school online at UNC Pembroke.”

Locklear showed me a portrait of his son. He wept while recounting the fourteen weeks he had been away from his son during basic training and the pride he had felt in seeing him graduate. “These boys would be put on the front lines,” Locklear said about the consequences of war with North Korea or another adversary. But just before my visit, the White House had announced direct nuclear talks between Trump and Kim. That gave Locklear a sense of hope.

“Now, looking back, maybe he was doing the right thing,” he said about Trump’s “hardball approach” with Kim. “Obama was too diplomatic; (Trump) is a straight shooter.”

By the fall of 2018, Locklear said of Trump, “I think he’s done a good job overall as president.” He added that he had not talked to anyone who voted for Trump who had changed their mind, and he thought Trump was on target to win Robeson County again in 2020. “People in my area value common sense over intelligence or book learning,” he said. “And that’s why they like Trump. He appealed to them at their level. And I just don’t think that’s going to change…. I haven’t made up my mind about whether I’ll support Trump again in 2020,” Locklear added. “But as of now, I’d vote for him.”

***

I made my final visit to Robeson County in January 2020, nearly three years after my initial trip. I returned with the goal of answering two questions. First, how was President Trump faring among the county’s pivotal Native American voters, and second, how was the economy, which Trump had made the centerpiece of his reelection campaign, affecting people in this impoverished county?

With Locklear’s help, I interviewed nearly a dozen Native American residents. At a school board fundraiser in Pembroke, three middle-aged women told me that while they were repelled by some of Trump’s conduct, they appreciated what he had accomplished on the policy front. And none responded favorably to my mention of Trump’s potential general election opponents, including former Vice President Joe Biden.

At a farm in Prospect, Donovan Locklear (no relation to Mark), a corn and soybean farmer, said he supported Trump’s trade war with China. “I think four more years of Trump holding China’s feet to the fire, they’re going to come to the table and be willing to negotiate even more,” the farmer, a registered Democrat, said. “I don’t like everything that he does, all the Twitter action. But at the same time, everything he told me he was going to do when he ran for president, he’s done.” That included Trump’s promise to defund Planned Parenthood and his signing of “right-to-try” legislation, which allows gravely ill patients to access experimental medicines. Donovan estimated that 90 percent of farmers would back Trump in 2020.

Donovan’s brother Jason, a chiropractor, joined the conversation and began railing about the media’s refusal to give Trump credit for his accomplishments. “I don’t see anything wrong with putting America first,” he said. “I don’t see anything wrong with controlling our borders. (Trump) never said anything negative about immigrants. He talked about illegal immigrants.…The more the media colors what Trump says, the more it makes me want to vote for him again.”

Later, I met with Virgil Lowery and McDuffie Cummings, who I was told had a better sense for local politics than just about anyone in the area. “The Democrat party is too left for the grassroots people,” said Cummings, who had served as supervisor of Pembroke for three decades. “They’ve gone with all these liberal ideas. Robeson County is basically conservative. It’s a conservative county!”

“You saw it with (Joe) Biden,” Virgil said. “He used to be a moderate on abortion. Now he’s moved all the way to the left with AOC…. We have a lot of conservative people in this county as far as their morals on homosexuality,” Virgil said. “Those kind of issues stirs the folks in this area and causes them all to vote and vote against the Democrats.”

“Democrats are just…they’re out of sync,” Cummings added. “The Democratic Party is not what the party used to be fifty-five years ago. It’s just changed. It went liberal, and it’s going to the left farther and farther.”

***

Before my visit to Robeson County, I asked several of my local contacts to notify me if they ever heard of any “switchers”—that is, people who had voted one way in 2016 but planned to vote another way in 2020. My contacts, among the most well connected people in the county, came up mostly empty. One exception was John, whom I interviewed one evening over dinner at San Jose Mexican restaurant in Lumberton. (He asked that I withhold his last name.) John, a former civics teacher in his late thirties, is a Robeson County native who moved to Northern Virginia before returning with his wife and kids a few years ago to be closer to family.

A conservative Republican, John said he believes there is a moral authority that comes with being president, a moral authority that he felt Trump lacked in 2016. Trump was too much of a “brawler” and “instigator,” John said. So on election day, he voted for Republicans in all the down-ballot races but left the presidential contest blank. But John informed me that he had since committed to voting for Trump in 2020.

I asked him what had changed.

“His Twitter account still kills him,” he said. “But Trump has actually done what he said he would do.” John contrasted Trump’s decision to move the US embassy in Israel to Jerusalem with the hollow promises of previous administrations.

“Also on trade policy, they just passed the USMCA—it was like, “Wow! …The guy told you what he’s gonna do, and he did it.”

More and more, as Donald Trump’s presidency unfolded, I began to hear from Trump’s supporters this same sentiment—that Trump has largely done, or at least tried to do, what he promised he would do. I even began hearing it from Trump’s critics. “His base is happy because he’s done what he told them he’d do,” John McNeil, the former head of the county Democratic Party, told me. McNeil acknowledged that the strong economy and the national Democratic Party’s leftward shift would be big barriers to Democrats’ success locally.

When I asked whether he thought Trump would win the county again, he let out a resigned laugh. “I’m scared of him,” he said. “I’m scared of what he will do to our country and to our fundamental values. I’m going to do everything I can do to make sure he does not win. But I don’t know if it’ll be enough.”

Donnie Douglas, editor of The Robesonian newspaper, also seemed sure Trump would win in the county again. Douglas believes residents continue to be disappointed with Trump’s “boorish behavior” but continue to support his “America first agenda.” Douglas said he knows people would “love a viable alternative to Trump but just don’t see that at all in the crowd that Democrats have put together…. Yes, I think Trump will win Robeson County again,” Douglas concluded. “We love our guns, hate abortion, don’t like gay marriage, and on and on, on social issues in which we align with Trump.”

My final stop was to see Channing Jones, executive director for the Robeson County Office of Economic Development. When I arrived, Jones, who has worked in manufacturing and academia, told me that the local economy was performing better than it had done in more than a decade. “The economy is doing very well right now,” he said.

I mean, most economic indicators are just tremendous. In November of ’19, which is the last snapshot we have, our unemployment rate was 4.9 percent in the county, down significantly from the 6 percent it had hovered around for years. It’s the lowest I can remember, and I’ve been tracking it for twelve years.

Jones stressed that manufacturing was still a crucial part of the local economy—17 percent of the county workforce still works in that sector. But food processing had replaced textiles as the dominant manufacturing industry. As an example, he cited Sanderson Farms, a chicken processor, which arrived in 2017 and invested $115 million in a plant and hired more than 1,000 people.

Jones had also seen growth in new homes, small businesses, and health care facilities over the last three years. “I don’t think you can go down many towns in our county and not see a ‘Help Wanted’ sign somewhere,” he said. “In general, if someone is looking for a job, I think they can find it now.”

I asked Jones what role, if any, the Trump administration had played in the strength of the local economy.

“Everything with the economy is based upon confidence,” he started. “If I gave you a doom and gloom picture, most investors are going to be very hesitant. I think that over the Trump administration, there has been a high level of confidence in the economy. That’s been great for our county.”

He called the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which President Trump was scheduled to sign into law that day, “a great thing,” mostly because it would lift the cloud of uncertainty that had hung over many industries for years. “I think Trump’s appeal is that, whether you like him or not as a person, most people can respect the fact that he said, ‘I’m going to do X,’ and he’s legitimately tried to do it.”

But Jones emphasized that the strong economy was only a part of the reason why he felt Trump would win the county and the state. He said that Trump’s positions and policies on “some very significant moral issues, faith-based issues,” would be the most important factors working in Trump’s favor. “Remember, we’re in the Bible Belt down here,” Jones said. “And it’s going to be hard for many people to not think about that when they go to the polls.”