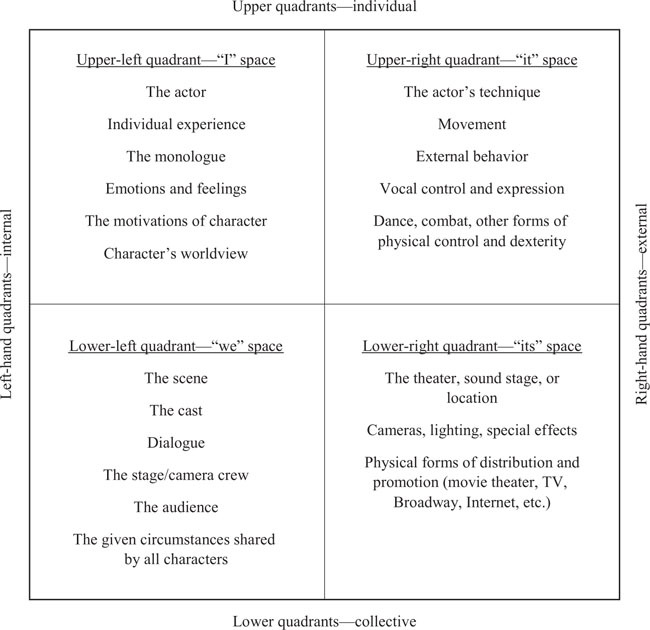

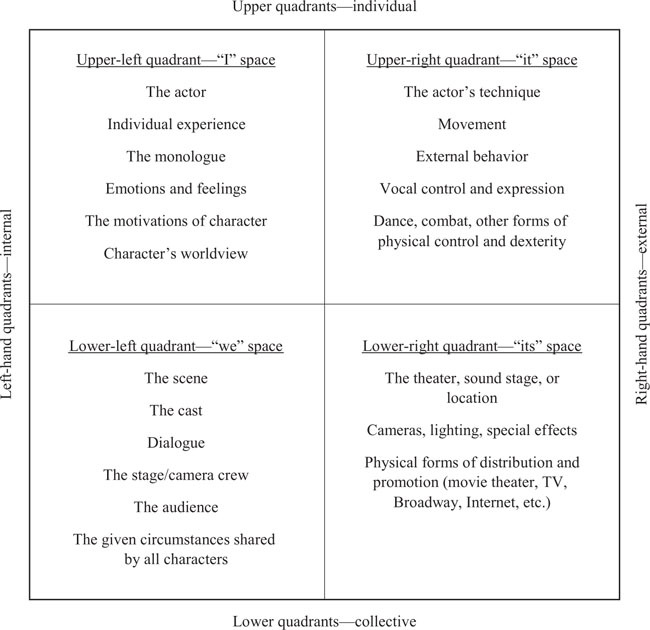

Figure 8.1 The theatrical event expressed in Wilber’s quadrants

Source: © Kevin Page

Ken Wilber (1949–) is an American philosopher and writer who has produced over 20 books that have been translated into dozens of languages. He began his publishing career as a transpersonal psychologist (a field described in Chapter 1) by proposing a “spectrum of consciousness” model that attempted to integrate the modern understandings of developmental psychology with the philosophies of Eastern and Western spiritual traditions (Wilber, 1977). Wilber, in other words, attempted to marry scientific reason and spiritual experience in a description of reality that took into account both seemingly contradictory positions and, at the same time, treat both positions seriously, a feat that many have tried yet most have failed to accomplish.

Wilber himself apparently has an exceptionally high IQ (as did Abraham Maslow before him) and is a voracious researcher who, after having dropped out of medical school around the age of 23, began a detailed literature review of such diverse fields as psychology, Western and Eastern philosophy, anthropology, biochemistry, the history of science, religious history, cultural studies and postmodernism, and art and literary criticism. In addition to his studies, Wilber is a serious meditator, and studied with a number of renowned meditation teachers concurrent with the development of his theories (Wilber, 1999c, p. x).

Quadrants, Levels, Lines, States, and Types

Wilber has gone through several stages in his work, evolving what eventually became known as integral theory, a worldview that seeks to account for all of the fundamental dimensions of reality, internal/external, individual/collective, in a comprehensive holistic synthesis or meta-theory, similar to what Maslow attempted for psychology, but with much broader implications. According to Wilber, any map or model that attempts to integrate all the fields of human endeavor into a cohesive understanding that honors and includes the greatest number of perspectives must, at a minimum, take into account:

Quadrants. The subjective (or interior perspective), the objective (or exterior perspective), and an individual and collective perspective (from both an interior and exterior viewpoint), which can be represented by a grid with four quadrants. Each quadrant of this grid represents an irreducible, fundamental aspect of reality at any given moment in time.

Levels represent the various progressive stages of development that living beings (particularly humans) evolve through, from pre-personal to personal to transpersonal. Various descriptions of levels or stages of psychological development, for instance, have already been described by many of the theorists we have covered in this book, including Erikson and Maslow. Levels, or stages, is essentially the idea that development of almost anything progresses through a series of patterns, generally from less complex to more complex, while including but exceeding each previous level in the progression; another term for this might be “growth hierarchy.”

Lines are the discrete domains or characteristic qualities of individuals (such as intelligence, emotional, interpersonal, moral, spiritual, physical, etc.) that can develop through their own levels or stages generally independent of the other lines. (As you will recall, Anna Freud introduced the idea of developmental lines into psychology.) So, for instance, you could have a person who is highly developed intellectually but with very low interpersonal skills. Another example might be a highly skilled athlete whose body has been developed to a very high degree but who might have very low moral development or little emotional control. Lines typically develop through an identifiable sequence of levels or stages.

States refers to “states of consciousness.” There are many different states of consciousness that people are capable of experiencing. For instance, when you wake up in the morning and go about your business, you are in what is considered a “normal” waking state of consciousness. But at night, when you go to sleep, that waking state transforms into something completely different. A third state of consciousness, radically different from those first two, is the dream state. Consciousness can also be altered from the “normal” waking state by various external forces or environmental elements. For instance, sleep deprivation, starvation, concussion, or brain damage can all have an altering effect on consciousness. Think about spinning in circles until you become dizzy as an intentional way of altering consciousness. Another example of an altered state of consciousness would be the influence of intoxicating drugs or alcohol, which can significantly change the normal waking state, altering perceptions and thought processes. Also, a set of discrete states of consciousness can be generated by activities such as extended meditation and deep yogic practices that disclose very different types of perceptions and cognitions from normal waking consciousness. Such states can include “enlightenment” or “spiritual” experiences, which historically have been described as changing the personalities of their experiencers in fundamental and potentially long-lasting ways.

Types is a kind of catch-all category for things such as male/female, introvert/extrovert, and other types of distinctions of difference and phenomena that don’t fit in the other four concepts.

So, by including all of these basic dimensions or perspectives, what Wilber calls an AQAL (pronounced “aw-qwal”) approach—which is shorthand for “all quadrants, all levels, all lines, all states, and all types”—one can create a radically holistic representation of reality that seems to be able to explain, and integrate, almost every human discourse or philosophy, belief system or spiritual tradition, academic field or worldview, as well as physical reality from the Big Bang to modern human history, as a single grand set of true-but-partial perspectives on a completely cohesive and harmonious universe. In other words, to the degree that you subscribe to Wilber’s comprehensive view, the argument between Plato and Aristotle, religion and science, and a lot of other folks has finally been resolved.

The AQAL Approach and Integral Psychology

The above may seem like an awful lot to bite off and chew in a book about psychology directed at actors, so let us focus on one explicit application of Wilber’s integral theory. In 1999, Wilber published Integral Psychology, which utilized his integral theory (AQAL approach) as a lens for integrating over 100 schools of psychology and spiritual traditions (often considered Eastern psychology) into a single overview of the human experience. It was a massive endeavor, and brought to fruition Abraham Maslow’s dream of a meta-theory of psychology that would honor, and make sense of, all of the previous schools of psychology, from Freud to Adler, to Horney to Erikson and beyond, while including the farther reaches of humankind (spiritual and religious, what Maslow called “peak experiences”) that were only being discovered and investigated for the first time, in the West, in Maslow’s day.

The AQAL approach begins with the premise that no human being is capable of generating 100% error. Therefore, there is something true about every idea, vision, or perspective. Wilber uses his metamodel as a type of infrastructure to “bolt on” other people’s theories and ideas, and get the varying truths to align and agree with each other. That doesn’t mean that there are not contradictions among various viewpoints (religion versus science, for instance), but viewed from a high enough level, and utilizing the various fundamental perspectives that Wilber has identified as organizing generalities, most systems of thought can actually be brought into some level of agreement.

Starting with his first approach, the spectrum of consciousness view, Wilber theorizes that consciousness evolves or develops (across all its potential lines) from preconscious to conscious to superconscious (what in Eastern philosophy has traditionally been called “enlightenment” or unity consciousness). In other words, consciousness tends to “unfold” or evolve through a series of stages that are progressive, and the earlier of those stages have been studied by Western psychology (Freud’s model of the unconscious, Erikson’s model of development, etc.), whereas the later stages of consciousness development have mostly been the subject of Eastern religious and spiritual philosophies. However, all of these stages are part of a unified developmental whole.

Western psychology has tended to ignore or deny the spiritual realms of human existence (and development), while Eastern views of human experience, such as Buddhism and Hinduism, have tended to only focus on the latter, more advanced stages of spiritual development and ignore aspects of the ego, the unconscious, and sociocultural developmental factors that Western psychology has tended to explore. For Wilber, both views are essentially correct; they are just looking at different stages or levels of development across different lines and not getting the whole picture. Another way to view this is that Western psychology, for the most part, has looked at development in lines such as psychosexual (Freud), psychosocial (Horney and others), and individual or ego (Jung, Anna Freud, etc.), while Eastern philosophy’s domains of concern have primarily been the spiritual line or consciousness itself, all of which are legitimate (and mostly independent) lines of development in human beings. Wilber’s stroke of genius here is in demonstrating, through a detailed review of the research, that all of these perspectives, Eastern and Western, are pointing at the same grand unfolding of consciousness, only usually from limited viewpoints that only account for one or two of these developmental lines at a time, while trying to ignore or deny the others. When all of the possible lines are taken into account (Wilber has identified over 20), and their general features or stages of development are mapped, suddenly the myriad forms of Western psychology (several of which we have already reviewed in this volume), and many of the spiritual systems from the great religious traditions of the world, seem to fit together in a larger puzzle that describes human experience and growth as a unified whole, from body to mind to spirit (Wilber, 2000a, 2000b, 2000c). This is the power and elegance of Wilber’s integral (AQAL) model.

Taking all of this into account, then, Wilber built a series of charts that correlated nearly 100 systems, both Eastern and Western, with each other across a number of dimensions suggested by the AQAL approach (Wilber, 1999b, pp. 197–217). He also noted that as people grow through their own developmental stages, they can have problems or deficiencies that cause pathology. In fact, Wilber proposed that many of the mental diseases that Western psychologists have identified are actually associated with different stages or levels of development, and that individuals, depending on their stage of development, might be subject to different types of mental pathology. In other words, things can go wrong in an individual’s life at any stage of development and, depending on the stage, cause different forms of mental sickness. For instance, a person who was severely abused as a young child may never develop a fully stable ego structure and be subject to a borderline personality disorder for life. But another person who had a relatively stable and secure childhood, and has had the opportunity to develop through several life stages into an otherwise “healthy” adult, might suffer the loss of a job or a painful divorce that challenges their feelings of stability and self-worth (Maslow’s belongingness and esteem needs; Erikson’s generativity vs. stagnation) and fall into major depression, a different type of mental pathology.

For the actor, Wilber’s integral theory is a very rich stew indeed, offering numerous perspectives on characterization rarely found in any version of contemporary acting theory. As a part of this book, I will barely be able to scratch the surface of these subject matters, and so recommend a full reading of Wilber’s work to any serious actor who wants to expand their own worldview and capacities to understand the human experience. Several of Wilber’s books can be found in the references section that follows this chapter.

Integral Psychology Exercises for Actors

Perhaps Wilber’s most important contribution is his quadratic model of reality and consciousness. The quadrants, as stated above, represent four fundamental perspectives that cannot be reduced, or ignored, in any full accounting of existence-in-time. Fundamentally, Wilber’s quadrants are the internal and external views of the individual and collective aspects of reality. These four views can be expressed by a grid divided into four parts (quadrants), labeled starting in the upper left-hand corner (and proceeding clockwise): individual (internal), individual (external), societal or systems (external), and communal or cultural (internal). Below is a representation of Wilber’s quadrants applied to the actor (upper-left quadrant) within a theatrical context.

The quadrant model (or lens) provides a very powerful way of analyzing and understanding or interpreting the theatrical event. By taking into account each of these irreducible perspectives in approaching a play, film shoot, or other type of theatrical expression, we can get a much more comprehensive view of “what is going on in the moment” than merely the actor’s individual perspective (which is wholly included in the upper left-hand quadrant view), the director’s objective perspective (which is wholly included in the right-hand side of the model), or the audience’s subjective perspective (which is wholly included in the lower left-hand quadrant view). Therefore, Wilber’s quadratic model becomes a way of capturing all of the fundamental elements (or perspectives) of a production, making it a very powerful tool that includes, among several other items, all of the psychological theories we’ve investigated to this point.

Figure 8.1 The theatrical event expressed in Wilber’s quadrants

Source: © Kevin Page

Experiencing Wilber’s Quadrants

The “I” Perspective

Working alone, perform a monologue that you already know well. What is your internal experience of performing that speech? What are your emotions? What images run through your head as you say the prescribed words? How does your body feel? What is the sensation of movement? How about your voice? What does it feel like when the speech speeds up or slows down? When the inflection rises or falls? Bring yourself as fully as you can into the present moment while performing this monologue, and whatever sensory or mental impressions you have of your personal experience (which includes the inner monologue of the character) is the “feeling” of the upper left-hand quadrant, the sensation of the purely subjective, the experience of the experience.

The “We” Perspective

Now think of how it feels to be a part of a large crowd or the audience at a concert, the cheering, the shouting, the spontaneous applause; the feeling of being drawn together with a group to act as one is the feeling of the “we.” This is the internal experience of the intersubjective dimension or the collective “we” perspective.

The “we” perspective is entering into the collaborative process of a production, the working with a scene partner, the director, and the rest of the cast and crew to “get the scene right.”

Perform a scene with a scene partner (or multiple scene partners). What is the interaction like between the various players on the stage? What is the feeling of nailing your blocking, of getting the timing just right, of affecting and being affected by the other players as you move through the actions and the moments of the scene together? Does it feel like a dance? Or like playing in a band? You can perceive the sensation of the “we space” when you enter a conversation and discuss a just completed scene in terms of “How good were we?” “How can we make the scene better?” “Were we funny or just boring?” “I think we should pick up the pace here.” So, the perspective represented by the lower left-hand quadrant is the internal experience of the intersubjective or communal during performance (or rehearsal).

The “It” Perspective

Now consider all of the props you dealt with in the course of the scene you just completed. Perhaps run through the scene again, this time focusing on the physical actions that constitute the forms and rhythms of the scene. What is the timing of that upstage-left cross? How do you physically handle that teacup you drink from? How do you sit in that chair? What are the technical elements of the stage fight near the end? Focus on the physical, repeatable behaviors and technical requirements of performing this scene on this stage or in front of these cameras. How closely do you hit your mark? What is your distance from the camera lens for your close-up? How many times must you repeat these exact actions before the director calls cut and you “have it in the can”? These are all examples of the upper right-hand quadrant, the “it” dimension of reality (or in this case, performance). Understanding and mastering the technical elements of any performance is another indispensable element of being a good actor. Notice that all of the internal, emotional, and interpersonal activities of the scene (the left-hand side of the model) are all still taking place simultaneously, but technical (external) execution is also an integral part of successfully completing the scene as an actor and as part of a cast or ensemble.

The “Its” Perspective

Along with your specific physical interactions with the set, props, and other actors during a performance, you are also performing in a certain space and under certain conditions. These conditions are informed by the infrastructure or context for the overall production and the production’s delivery into the public sphere. In other words, your individual performance may be a part of a movie, TV show, stage play, or Internet video. Whatever the case, your performance happens under certain circumstances, and each of those sets of circumstances has different sets of requirements that an actor must understand and be able to execute in order to successfully complete their job on a set or during a live performance. These circumstances, and commensurate requirements for success, are what are “contained” in the lower right-hand quadrant of Wilber’s model.

For most roles, an actor must audition. Understanding what that protocol is under various conditions is very important. An audition for a role in a movie that takes place in a professional casting studio in front of a casting director and a video camera is very different than singing 16 bars from a Broadway show tune on a stage in a spotlight when auditioning for a musical. The same can be said for the general rules of a film set or a 500-seat theater; they are very different sets of rules, dealing with wholly different infrastructures and environments, and a successful actor needs to fully understand which circumstances she is in (and what processes and behaviors are expected of her) if she wants to successfully win and execute an acting job. These concerns and protocols represent the “its” or “systems” dimension of the acting process, and it is fundamentally different from the other three dimensions we have already investigated.

To experience this directly, compare two acting experiences you have had, one on a stage with a live audience, and the other on a film or TV set where you have performed a scene multiple times in front of a camera or cameras. How are the circumstances and expectations different? How do you have to adjust your performance to meet the different requirements? Make a list of these differences in protocol and performance venues for later reference. If you have not yet had experience in these various domains, it is highly recommended that you do, so that you will understand the professional, external behaviors that will be required from you during your career.

Using Wilber’s quadrant system as a way of understanding and analyzing the requirements of a particular acting challenge is perhaps one of the most potent tools ever developed that can be applied to the actor’s craft, simply because it requires you to investigate and deal with all of the important aspects of performance and does not allow you to ignore or remain ignorant of any of them. I have known many very good actors who were deeply personal in their emotional, mental preparations and performances, but lacked the practical, common knowledge of auditioning or film set protocols, so that they simply were not hired for certain jobs (and therefore never gained that experience). Using Wilber’s quadrants forces the actor to be prepared for the work at hand, both technically as well as psychologically.

Your Character’s Lines of Development

One of the major components of Wilber’s AQAL model is the perspective of development across multiple, mostly independent, lines that represent qualities or aspects of the human personality and consciousness. The idea is that these relatively discrete lines, most of which have been identified and studied by various researchers in Western psychology, develop through a set of relatively fixed stages that unfold in a predictable sequence that generally subsumes earlier stages within the later and more mature stages. In this sequence of development, one stage proceeds from the previous, and no stage can be skipped or bypassed. So, for instance, a child’s cognitive development, as described by Jean Piaget (Piaget, 1977, 1978; Piaget, Elkind, & Flavell, 1969), proceeds through four distinct stages: the sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete operational, and formal operational. In the sensorimotor stage, infants gain knowledge of the world from the physical actions they perform within it (movement, touch, sucking, etc.). In the next stage to emerge, preoperational, the child acquires language and develops the capacity for symbolic thought, although still retains the knowledge and learning that occurred in the previous stage. In this stage of cognitive development, the child learns “object permanence,” or the fact that things continue to exist even when they are not physically present and in view. At this stage, even though the child has greatly evolved since birth, they still cannot understand concrete logic and cannot mentally manipulate information, which is the next major growth stage. In the concrete operational stage, beginning around age 7, the child begins to develop logical thinking abilities, something that was not possible in the early stages, and therefore is an emergent of this more hierarchically advanced stage. In other words, in order to develop logic, one must first have the structure of language, and in order to develop language one must first have some control of their sensual impressions of the world around them; this is what is meant by “one stage proceeds from the previous and no stage can be skipped or bypassed.” At the concrete operational stage, the child becomes able to incorporate inductive reasoning, which involves drawing inferences from observations in order to make generalizations. However, at this stage, they still struggle with deductive reasoning, which uses a generalized principle in order to predict the outcome of an event; this ability to “abstract” does not emerge until the next stage. Formal operational thinking involves the logical use of symbols related to abstract concepts. This form of thinking includes “assumptions that have no necessary relation to reality” (Piaget, 1950). At this stage of cognitive development, the now adolescent is capable of hypothetical and deductive reasoning. In other words, they develop the ability to think about thinking and abstract thought.

Piaget’s model of cognitive development, even with certain flaws that have been pointed out by later researchers (Callaghan, 2005; Lourenço & Machado, 1996), remains a good example of a line of development that unfolds fairly independently (although it may to some extent be a prerequisite for some other lines). For instance, cognitive development will generally progress in the stages just described, regardless of development in other lines such as kinesthetic (athletic), musical, emotional, moral, spiritual, etc.

As mentioned above, Wilber, building on the work of other theorists, including Piaget, Kohlberg, Kurt Fischer, Abraham Maslow, Carol Gilligan, Howard Gardner, etc. (Wilber, 1999b, p. 29), identified more than 20 developmental lines that he felt were significant in terms of understanding individual psychological growth (the upper left-hand quadrant in his quadratic model). Some of these mostly independent lines include: morals, affects, self-identity, psychosexual development, cognitions, ideas of good/evil, role-taking, socio-emotional capacity, creativity, altruism, spiritual development, joy, needs (à la Maslow), logico-mathematical competence, kinesthetic skills, empathy for others, etc. The interesting thing about Wilber’s (and other developmentalists’) theories about lines of development is in the aforementioned “independent” quality, meaning that if each line can develop relatively independently from the others, then overall development ends up being a completely unique and individual affair, with each person highly developed in some areas, modestly developed in others, and perhaps deficient or severely underdeveloped in yet other capacities or qualities. One hypothetical example of this kind of “uneven” development might be the successful politician who has developed strong communications and interpersonal skills (enough to get elected to high public office), and yet has very poor moral development or even pathologies in psychosexual development. Such a person might wield great power and command much respect from peers and constituents, yet become embroiled in a sex scandal where they abused their position of power to inappropriately solicit a sexual relationship. Another hypothetical case might be the world-class athlete who has developed their kinesthetic senses, reflexes, musculature, hand–eye coordination, etc., but has spent very little time and effort on other forms of education and cognitive training, so that their reading and reading comprehension is very low.

Building a Developmental Lines Profile

Start by taking a careful look at yourself. Assess the areas or skill sets that you feel represent your strongest or most developed qualities. (You might start by looking over the list of developmental lines that Wilber has identified above, but feel free to list your own as well.) Make notes in your written or audio journal. Now add to that list the areas or skill sets where you feel you are only “average” or could definitely use some improvement or growth. Finally, list the areas where you are the weakest, have deficiencies, or aspects of yourself that actually cause you problems. We will call this your developmental lines profile (DLP).

Now look at your DLP and ask yourself which of these lines you could improve with some form of effort. If you are out of shape, for instance, you could always add exercise into your daily routine. If you feel you are a little low on empathy, perhaps you could dedicate some time to charitable works or helping others. The point of this exercise is to identify your own unique DLP and to use it to find ways to improve or balance out your talents and gifts.

Once you have some familiarity with your own developmental lines and DLP, try building a DLP for a character that you are working on or that you already know well. Use the given circumstances of the script or the content of the dialogue to suggest those developmental lines where the character may be overdeveloped or underdeveloped. Perhaps there are some areas where the character may be so underdeveloped that they exhibit pathology (such as in the hypothetical politician above).

How do various character DLPs inform or change the ways you might play a particular scene? What if your character was very smart or educated? Or not very smart at all? Would this change anything in your performance? What if your character were excessively moral and honest by nature? Or, conversely, what if they were a moral despot with a sociopathic disregard for other people’s feelings? Experiment with different combinations of developmental lines and see what they bring up in terms of creative possibilities.

As mentioned above, Wilber has written dozens of books and has been very prolific in applying his integral theory to multiple disciplines and areas of criticism. As such, I have only been able to touch on a minor fraction of what Wilber has taught that might have significant value to the actor. I would go as far as to say that a full application of Wilber’s theories to the actor’s craft might well represent the first theory since Stanislavsky’s to be comprehensive enough to capture the full subtlety and range of the serious actor’s art. However, it would take an entire book (and perhaps a series of books) to explicate the possibilities. Until then, I highly recommend reading Wilber’s original works in other areas such as psychology (Wilber, 1999b), consciousness studies (Wilber, 1999c; Wilber, Engler, & Brown, 1986), postmodernism and philosophy (Wilber, 2000b), anthropology and cultural studies (Wilber, 1999a), and meditation practice (Wilber, 2016). One word of warning on reading Wilber; some of his works are very academic and can be challenging, if not flat-out difficult, to read. He has, however, also written books to introduce his theories that are intended for a more general audience (Wilber, 2000a, 2007). These titles may be a better place to start with Wilber, and then explore his more challenging work once the basic concepts are clear to you.

References

Callaghan, T. C. (2005). Cognitive development beyond infancy. In B. Hopkins (Ed.), The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Child Development (pp. 204–209). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lourenço, O., & Machado, A. (1996). In defense of Piaget’s theory: a reply to 10 common criticisms. Psychological Review, 103(1), 143–164. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.103.1.143

Piaget, J. (1950). The Psychology of Intelligence. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Piaget, J. (1977). The Development of Thought: Equilibration of Cognitive Structures. New York: Viking Press.

Piaget, J. (1978). Behavior and Evolution. New York: Pantheon Books.

Piaget, J., Elkind, D., & Flavell, J. H. (1969). Studies in Cognitive Development: Essays in Honor of Jean Piaget. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wilber, K. (1977). The Spectrum of Consciousness. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House.

Wilber, K. (1999a). The Atman Project: Up from Eden. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (1999b). Integral Psychology: Transformations of Consciousness—Selected Essays. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (1999c). The Spectrum of Consciousness: No Boundary—Selected Essays. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2000a). A Brief History of Everything: The Eye of Spirit. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2000b). Sex, Ecology, Spirituality: The Spirit of Evolution (2nd rev. ed.). Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2000c). A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science, and Spirituality. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2007). The Integral Vision: A Very Short Introduction to the Revolutionary Integral Approach to Life, God, the Universe, and Everything. Boston, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K. (2016). Integral Meditation: Mindfulness as a Way to Grow Up, Wake Up, and Show Up in Your Life. Boulder, MA: Shambhala.

Wilber, K., Engler, J., & Brown, D. P. (1986). Transformations of Consciousness: Conventional and Contemplative Perspectives on Development. Boston, MA/New York: New Science Library/Random House.