Before I address the impact of the culture of impossible parenting on birth, I want to touch on the politics of choice about even becoming a parent. All people, but especially those who identify as women, are warned that if they don’t have children they might miss out on their life purpose or never feel completely fulfilled.1 That’s a pretty significant threat! In a culture where childrearing remains the norm, negativity or ambiguity about having children is often regarded as risky behaviour. And once you decide to parent, any negative or ambivalent feelings about parenting can be read as personal flaws or weaknesses. You can find yourself trapped in a climate of coerced positivity, fuelled by the fear of being outed as an unwilling, incapable, or just plain bad parent. These feelings of “am I doing this the right way?” can begin the day you find out you’re expecting. They can also begin long before conception.

Western family culture is deeply informed by the concept of pronatalism, which is the idea that parenthood and raising children should be the central focus of every person’s adult life.2 This belief system includes assumptions such as the purpose of marriage is to raise children and becoming a parent is a necessary stage in the journey to adulthood.3 While all genders receive the message that parenthood provides the greatest source of meaning and contentment, pronatalism impacts women in a distinct way because it convinces them that a woman’s destiny is to become a mother, and that it is ciswomen’s “biological” instinct to want children.

When I first learned about Laurie Sanci’s work coaching women who did not have children, it had never occurred to me to question where my desire to have children came from. She explains that pronatalist ideas pervade every aspect of our lives. At school, sex-ed classes focus on when is the best time to have children, not whether or not to have them. At work, flexibility is often offered to parents because of their need for work/life balance, but less so to people without kids because it’s presumed that they don’t have lives that require balancing. Many new young couples are asked when they’re going to have kids, and feel pressured by their parents to produce grandchildren. “Pronatalism accounts for the relentless speculation in the tabloids as to whether or not Jennifer Aniston is pregnant, with the idea that until she becomes a mother, she hasn’t really made it,” says Sanci. “The media we consume is mostly absent of female characters who are not mothers or of childless couples, but when they do appear, they are portrayed as sad, desperate, or suspect in some way.”

There is, of course, nothing wrong with the desire to have children. The problem with pronatalism is that it makes parenthood mandatory for everyone and creates a stigma around not having kids. The desire not to have children becomes abnormal and unnatural. As Sanci says, “It makes women who don’t have them seem worthy of pity or scorn. It makes men who don’t have them seem immature. It makes marriages without kids seem pointless. And it creates a divide between those who have kids and those who don’t.” Have you ever noticed how different it sounds to refer to non-parents as child-less versus child-free? Pronatalism can lead people to believe that if they don’t have children, a life of joy, meaning, and purpose just isn’t possible; if they don’t have kids, they’ll miss out on the only experience that can really truly provide those things. Essentially, while parenting is incredibly demanding, becoming a parent also comes with of social privilege.

On the flip side, Sanci explains, pronatalism also seems to deem some people more “socially acceptable” for parenting than others. Financially independent, partnered, straight, cisgender, married, and able-bodied people are expected and pressured to become parents, while low-income, young, old, queer, or people with (dis)abilities4 are often questioned about their ability to succeed at it and their pregnancies are seen as immoral, selfish, or unwise.

Of course, there’s a lot of diversity among people who do not have children. Sanci points out that there are those who have made a conscious choice not to have children and who might use the term child-free to describe themselves. Others wanted to have children, but encountered barriers to doing so, such as infertility, not finding a partner in time, or not having the financial resources to be a single parent. These people, who are affected by circumstance, might be more likely to refer to themselves as child-less.

There is arguably no process where the limits of our control are more evident than in fertility. While I understand the biology of conception, the ability to become and stay pregnant still feels very mysterious to me. An estimated 16 percent of people who want to become parents will go through hell to try to carry a pregnancy.5 Even with our ability to create all the necessary biological conditions, through cycle monitoring, hormone dosing, or embryo implanting, fertility feels like a bizarre game of luck or chance. Some people with known fertility concerns, such as polycystic ovaries, fibroids, endometriosis, or partners with low/inactive sperm, are able to get and stay pregnant easily, while others with no known concerns do not. Just as strangely, some people conceive easily for their first pregnancies, but then struggle to conceive again (often referred to as secondary infertility). The messages about fertility seem to target women and centre largely around age, with many people under thirty not expecting to struggle, while those over thirty-five get to enjoy medical terms like “old eggs,” “high risk,” and my favourite, “geriatric pregnancy.”

The emotional experience of infertility is intense, and the fertility process can easily take over your life. Not only because of all the tracking, scheduled sex, or early morning medical appointments, but also because of the emotional roller coaster of the repeated cycle of “I hope this is the month!” followed by the devastating disappointment of an unsuccessful try or a loss. The lack of control over fertility and the desperate frustration it can cause is escalated by our culture that is so deeply uncomfortable with suffering and loss.

Not surprisingly, depressed and anxious feelings are a normal part of fertility struggles. And then there’s the jealousy! When you’re trying to conceive it feels like everyone you know is getting pregnant and having babies, which can create significant internal tension — should you go to your friend’s baby shower and feel heartbreaking envy, or avoid it and feel like a bad friend? There’s so much that is unfair about infertility and it’s common to feel rage or a sense of undeservedness.

The fertility experiences of queer couples generally feels different than that of cis-bodied heterosexual couples, because for most of us there is no ability to have a spontaneous pregnancy at home. Some queer couples have access to both a uterus and sperm between them, such as transgender speaker, activist, and birth parent Trystan Reese and his partner, Biff Chaplow, or some use a known donor and attempt nonclinical pregnancy through penetration or at-home insemination. But I suspect that the majority of queer couples become pregnant through fertility clinics. For queer families trying to conceive, there isn’t necessarily a conception challenge to overcome, but rather an access-to-sperm-or-egg challenge. This presents its own set of inequities, because families where one or more of the intended parents has a uterus are significantly advantaged over those that do not, and many cis-bodied, gay male couples feel as though becoming parents will be an uphill battle.

Fertility treatments are also very classed. Intrauterine insemination (IUI, a procedure to put sperm in a uterus) is more affordable that in vitro fertilization (IVF, which involves several procedures, including egg extraction, fertilization and embryo development, and then implantation), and even in regions that provide funding for IVF cycles, intended parents still face many additional costs, such as pharmaceutical drugs, biological materials, or genetic testing. IVF usually requires time off work for cycle monitoring and insemination, and it’s harder to maintain privacy when you have to explain why you’re coming in late or taking days off. And while all fertility treatment is expensive, surrogacy can be prohibitively expensive, especially since our confusing legal system has not caught up with reproductive technology. And adoption is challenging in its own way.

Even when parents become pregnant through fertility treatments, miscarriages or nonviable pregnancies are common. I don’t feel that there’s enough support for pregnant parents seeking termination for a nonviable pregnancy that they desperately wish was viable, or who are carrying multiples and choose to selectively terminate. These can be very lonely, isolating experiences. There is so much potential for heartbreak for those who want to become parents. Reproductive rights remain deeply political, and access to various privileges determines who has the right to, who is enabled to, and who is encouraged to become a parent.

When families are successful in becoming and staying pregnant, the next major event they need to prepare for is the birth. Fantasizing and planning for birth is a rite of passage for all soon-to-be parents, including those who are pregnant and those waiting for a surrogate or adoptive birth. Contemporary birthing practices are the result of evolutions in medical technologies and health care practices, both of which are deeply informed by the politics of class, sex, and gender. To capture the last 130 years of birth history in Western culture, I interviewed Bianca Sprague, a doula with over fifteen years’ experience and owner of the doula training school bebo mia. She explained to me that historically most births were not deemed to be medical events requiring interventions, and they were often attended by community midwives or birth attendants. This all changed in the early 1900s when the rise of private medicine quickly led to 50 percent of births being attended to by doctors for a fee, with the other half being attended to by midwives. In 1920, American obstetrician Dr. Joseph DeLee argued that if obstetrics (then a novel and evolving field) was ever to be regarded as a medical specialty, births would require the routine use of analgesics, episiotomy, and forceps. This shifted our perception of birth; it went from a common experience to a medical event that required continuous monitoring and interventions. While birth always has an element of risk to it, it was rebranded as a dangerous experience that could only be facilitated safely with the help of Western medicine. This had a significant impact on birthing practices, and by the 1940s hospital births outnumbered home deliveries in most communities.

Birthing practices now vary widely depending on where you live, with the majority of North American births occurring in hospitals. And medical procedures to support safe birth, such as epidurals or surgery, can come with hefty price tags. This has less of an impact on birthers with government-funded health care or full coverage through private insurance, but it puts low-income and underinsured parents in a difficult situation. Some of my midwife friends (who support birthers in Ontario whether or not they have insurance) have shared with me some chilling stories of un-insured, newcomer birthers in Canada who are refused epidurals by hospital anesthesiologists until they pay hundreds of dollars cash, only to have to pay again if there’s a shift change and a new anesthesiologist comes on shift. While I have some deep critiques of the documentary The Business of Being Born, it did highlight stories of significant mistreatment of birthers in America, common among them the overreliance on C-sections and an overall attempt to streamline the process, which should be deeply personal and unique to each situation. Some stories about birther mistreatment by medical practitioners seem stranger than fiction, such as the 2019 public scandal out of North York General Hospital where Dr. Paul Shuen used induction medication to bring on labour in his pregnant patients without their knowledge or consent, in an effort to attend as many births as possible and maximize his revenue.6 Even more bizarrely, he was met with only minor professional and legal consequences.7

I don’t mean to demonize obstetrics. I understand that birth is complex and unpredictable. I personally experienced this and had a dangerous and traumatic birth with my first child. The experience was so intense the doctor on call offered my mother a sedative because she was so afraid of losing me or her grandchild. Although I found ways to exercise control over my body and my choices in the birth space, which was important to me, I have significant love and respect for the obstetrician who safely delivered my child. Instead, I share this history to contextualize the problematic experiences some parents have at birth, although Western medicine is not the only source of tension in the birth space.

The natural birth industry emerged in the 1950s as a response to mounting fears about losing choice and agency in birth, and confusion about the level of risk associated with uncomplicated births. Sprague explains that one of the founders in this area was Dr. Fernand Lamaze, a French obstetrician who promoted childbirth as an active, natural, and empowering event. He advocated for holistic, non-medical pain management techniques such as breath, visualization, and targeted body relaxation techniques. His work was so influential that by the 1960s there was a renewed interest in unmedicated childbirth, soon to be dubbed “natural” childbirth, resulting in an increase in medically unattended births or births assisted by non-legal midwives. In the early 1990s the demand for legal support for home birth led to the licensing of midwives in many states and provinces. Although the regulation of midwives and their scope of practice varies widely across jurisdictions, today midwives are, more often than not, legally able to provide medical care for those who want to give birth at home or the hospital. An entire industry of products, services, and courses designed to support unmedicated birth exploded, amplified by the keep it natural belief from the culture of impossible parenting. Books, childbirth preparation classes, hypnobirthing recordings, pregnancy yoga, portable TENS machines, birth tub rentals — there seems to be an endless number of things you can buy to try to have a “more natural” birth. A set of parents has also emerged who call themselves “free birthers,” defined as opting out of the obstetrical and midwifery systems entirely to give birth unassisted, generally because of strong libertarian or religious values, but also because they have felt traumatized by the medical system.

Although there is no universal definition of “natural” birth, many parents I know define it as vaginal, without epidural or induction, and possibly at home — with as little medical intervention as possible. And while birthers can refuse medical interventions, the challenge is that birthers who are committed to having maximum control and minimal interventions at their birth still expect a healthy physical outcome for themselves and their baby/babies. Unfortunately, that isn’t always possible, which has always been true for birth. Natalie Grynpas, a perinatal social worker who has worked with many free-birth parents to help them to fully explore the cost of their choices, suggests that some clients are so committed to birthing outside of the medical system that they are willing to risk death (their own or their child’s). Although they certainly don’t wish for it, they are able to accept it as a possible outcome. For some, this could be because of religious beliefs that the outcome of the birth is God’s will, while for others the thought of a negative outcome is less traumatic than the thought of losing control or freedom in the birth space.

An accurate assessment of potential risks associated with pregnancy and birth is difficult to come by. Even the most seasoned physicians or midwives can only speak in generalities and likelihoods. But we do know that not all parents have the same level of risk; racial disparities put Black and Indigenous birthers at a disproportionate risk of birth complications, including death.

Many discussions about risk associated with pregnancy and birth seem to be designed to either terrify parents about all that can go wrong or convince them that everything will be fine as long they keep away from medical interventions. Fear is what initially convinced parents to have babies in hospitals, yet some feel that the natural birth community uses fear to motivate parents to avoid hospitals, or at least medical procedures, during birth. The result is that it can feel difficult for some parents to find trustworthy information about safe birthing practices about their specific pregnancy. If the goal of the medicalization of birth was to increase parental and infant health and safety, and if the goal of the natural birth movement was to normalize birth and give people agency and choice in their experience, it doesn’t feel like anyone is winning. Instead we’ve told parents to pick a side. Sadly, when taken to extremes, both sides of this debate can feel unsupportive for birthers.

Interest in the emotional experience of birth has been getting a lot of attention over the last ten years. Though healthy mom, healthy baby has long been cited by medical practitioners as the ultimate birthing outcome, this idea of what constitutes a “healthy” birther is evolving to include not only physical health, but mental and emotional health as well. In 2018 the World Health Organization (WHO) published a commitment to patient-centred care in its report WHO Recommendations: Intrapartum Care for a Positive Childbirth Experience, which

recognizes a “positive childbirth experience” as a significant end point for all women undergoing labour. It defines a positive childbirth experience as one that fulfils or exceeds a woman’s prior personal and socio-cultural beliefs and expectations, including giving birth to a healthy baby in a clinically and psychologically safe environment with continuity of practical and emotional support from a birth companion(s) and kind, technically competent clinical staff. It is based on the premise that most women want a physiological labour and birth, and to have a sense of personal achievement and control through involvement in decision-making, even when medical interventions are needed or wanted.8

In order to try to protect the comfort and emotional support of birthers, many parents turned to birth doulas, who provide informational, emotional, and physical support to families during pregnancy and birth. This role on a birth team is not a new concept, as historically there were often female birth attendants whose job was primarily to care for the birther. What is new is that birth support service providers are now professionally trained, certified, and becoming a fast-growing, and often expensive, component of the birth industry. One of the strategies many doulas and other pregnancy support workers use is to help their clients make informed choices by helping them interpret information about their health, pregnancy, and birth options. The goal of informed choice is to clearly outline the risks and benefits of all testing and intervention options, and importantly, respect whatever decision(s) birthers make. While this is a worthy goal, it can be hard to truly achieve. For one thing, according to Grynpas, there isn’t really such a thing as informed choice, because it’s impossible to fully understand the outcomes of each choice ahead of time or how you will feel about them. For example, a client committed to vaginal delivery over surgical birth may know that vaginal birth comes with increased risk of pelvic-floor damage, but it’s very hard to fully grasp what it might be like to live with chronic fecal incontinence.

Another challenge to empowering birthers to make informed choices is that medical professionals can be held liable for choices that are made during a birth, so they have a vested interest in the outcome. There’s an incredible amount of pressure on medical professionals to always have the right answer and to never make mistakes, which is understandable because birth can be a matter of life and death. Liability aside, they also want good outcomes for their clients! I have worked with many medical professionals who feel incredible tension between their desire to support their client’s choices and their fear for the client’s well-being. Feeling torn in this way can be terrifying and can cause vicarious trauma for midwives, nurses, and doctors. There’s also legal confusion about whose life takes priority: the birther or the baby? And who gets to make that choice? The medical staff? The birther? The partner? This becomes even more confusing in the case of surrogacy births, where there are two families’ interests on the line.

A third difficulty with informed choice is that a birther’s choices may not always be practised or even allowed where they give birth. There’s a difference between evidenced-based care and practice-based care. Although we’d like to expect that medical practices will evolve to stay up to date with research and recommendations, there’s often a significant lag between what research suggests (evidence-based care) and this is how we have always done it here (practice-based care). A good example of this is antibiotic eye drops that are administered to babies after birth. Ophthalmia neonatorum is an infection commonly found in babies born to parents with active sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and it can cause vision defects. Before we had heightened public awareness about STIs such as chlamydia or gonorrhea, before condoms were readily available and popular, and when soldiers were returning home from war having contracted STIs through sexual encounters while away and unknowingly infecting their spouses, some babies born vaginally would contract ophthalmia neonatorum.9 In response, recommendations and laws were enacted to give antibiotic eye drops to all newborn babies. These measures did reduce vision problems in at-risk babies, but today we treat STIs during pregnancy, so the need for antibiotic drops is much smaller. There are some minor risks to giving antibiotic eye drops to all babies, so the current evidence lends itself to the recommendation of only giving eye drops to babies that have a high risk or that show signs of infection. However, in places where antibacterial eye drops remain the law and hospital practice, parents can face investigation by child protective services for refusing to allow medical staff to administer the drops, even though it is no longer recommended by numerous medical associations — so even the most well-informed birther may not be able to choose when it comes to eye drops.10

Unfortunately, the result of all this confusion, unmet expectations, and lack of support is a substantial amount of birth trauma. It’s so common that about a third of all birthers report feeling traumatized by the process.11 I’m not going to give detailed horror stories here, but I will write plainly about common traumatic experiences, so this section may be difficult or triggering for some. Please take care of yourself accordingly.

Birth and reproductive trauma are not the same as PPD/A, but I do put them in the broad PMAD bucket that I usually refer to as postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (PP-TSD). Trauma affects the brain and body differently from PPD/A, and although you could have both, each requires different treatment and support. I don’t think birth trauma gets treated with the same levels of care and awareness that other forms of trauma receive, such as sexual or physical violence, relational or childhood trauma, or war and natural disaster trauma. Many of my clients share this sentiment, saying that unless they’ve experienced physical or loss trauma (described below) they feel confused about where to go for help. The “healthy baby and healthy parent” mantra makes non-physical PP-TSD invisible. There’s a sense that if everyone is okay, you should just be grateful; go home and enjoy your baby and forget about it. And yet we would never tell a hurricane survivor to just be grateful that they made it out alive and to enjoy the nice weather now that it’s over.

Birth trauma is also minimized because medical staff are familiar with crisis and comfortable with surgery while many of us are not. I don’t believe that the majority of medical staff mean to be dismissive about our birth experiences, but I do think they can tend to miss what the experience is like for the patient because they’re so focused on the medical response to the situation rather than the emotional. Some birth professionals may act overly calm in an attempt to reassure anxious patients that they have everything under control, which can be annoying to clients who want to have their feelings validated. Also, birth professionals are concerned about complaints or liability, so they might try to frame what happened as small and commonplace to avoid repercussions.

Birth trauma is also unusual because we don’t usually expect to go through a trauma multiple times! But any birther who wants to carry future children is faced with a difficult decision, knowing that they could be triggered or that they could suffer a new trauma. Depending on what happened at their first birth, they may have limited options for subsequent ones; for example, it can be difficult for someone who’s had two surgical births to find a practitioner who’s willing to support a home delivery, or the opposite, someone who wants to have a surgical birth can feel pressured into a VBAC (vaginal birth after Caesarian). I’ve heard many clients say that they desperately want to have more kids but aren’t sure they can “go through that again.”

Of course, it isn’t always what happens during the birth itself that’s traumatic. Sometimes it’s what happens immediately after the birth or in the weeks just prior or just after. This is why I refer to it as birth and reproductive trauma. Over the years, I have seen reproductive trauma show up in a few different ways, and given my sudden uptick in birth trauma client work directly related to the pandemic, I suspect there will be a new category of “pandemic trauma.”

Sexual Trauma: People who have a history of sexual violence are particularly vulnerable to trauma during birth. Giving birth is an incredibly vulnerable experience, but it’s especially so when your body has been violated in the past. It’s not very often that we are asked to undress and have our genitals displayed and touched by multiple strangers. That alone can be retriggering for a sexual-violence survivor, even if they are deeply respected during the birth. Many sexual-violence survivors say that during their assault they experienced a loss of control over their body, that it was robbed from them, and so they’re anxious about losing control over their body and their choices during their birth. When a birther gets an epidural for pain management, parts of their body are numbed, and surgical birth usually involves having a curtain placed between the birther and the surgical staff. While this makes sense — the curtain protects them from having to watch surgery being performed on their body — it can feel like a total loss of agency to have limited sensation and no visuals but to feel tugging and pulling in their abdomen. It’s also true that sometimes during birth, consent is violated. During my doula years, I saw situations in which birthers said, “No, stop — that hurts!” during cervical checks but the medical staff kept going, saying, “Just one more second — I’m almost done!” To be clear, this is never okay, but it can be especially traumatic for a sexual trauma survivor.

Physical Trauma: Physical trauma occurs when birthers experience unmanaged pain or suffering in their body during the birth, or when they or their baby/babies become unsafe or come close to death. This can happen if an epidural doesn’t work, or if a birther becomes violently ill for the duration of the birth. Physical trauma can also stem from an emergency, such as low fluid, (postpartum) pre-eclampsia, placenta or heart rate issues, a micro-preemie baby, or a baby that’s born lifeless. Trauma also commonly occurs when a birther gets into a crisis and needs to be suddenly fully anesthetized for a surgical birth, as it is a very confusing experience to go to sleep pregnant and wake up with the baby having been removed.

Surviving the birth is only one aspect of it; physical healing is another. There are times when there are long-term physical consequences of giving birth, such as severe tearing, wounds that don’t heal or that get infected, prolapses, emergency uterus removal, or babies that develop unexpected (dis)abilities related to events during the birth or shortly after it. Physical trauma can affect the ability to bond with or care for a new baby, leaving many birthers turning to friends and family for support they were not expecting to need.

Emotional Trauma: With my clients, this most commonly occurs with people who have experienced a loss of control over their bodies or their choices, such as a consent violation, an extremely rapid birth, an unplanned surgical birth, an assisted delivery, or being given an episiotomy without discussion. It can also stem from an emergency transfer to the hospital when a home or birth-centre birth becomes too risky. Sometimes birthers feel emotionally traumatized by feeling disrespected or not listened to by their birth team, or by having a partner who doesn’t make it in time or is not adequately able to support them during the birth.

Trauma can often be avoided in birthers who have to deviate substantially from their ideal birth if they are given enough time to understand the risks and opt to change course, rather than being told what is going to happen next. They might feel disappointed, but still be able to process the experience. But unfortunately this doesn’t always happen; emotional trauma is often overlooked as long as everyone is considered physically healthy.

Structural Trauma: This occurs when clients feel oppressed or excluded in the birth space based on an aspect of their identity that has been historically (and continues to be) marginalized. Many people who identify with a marginalized group have personal and intergenerational histories of structural trauma and microaggressions, and the birth space can quickly become unsafe or re-trigger them. For example, when I was a doula, one of my Black clients was accused of lying about her drug use during pregnancy (she didn’t use any) by a white nurse who couldn’t believe that someone who lived in “that part of the city” wasn’t using drugs. In another case, an Indigenous birther, who was also a doula, was forced to have a conversation with child protective services before she was “allowed” to leave the hospital with her baby because she disclosed that she’d used some prescribed THC during pregnancy to manage pain. I’ve heard many parents with both invisible or visible (dis)abilities needing to prove their parenting competence to medical staff before taking their baby home. Trans and genderqueer parents run the risk of not having pronouns respected and birthers with large bodies often describe body shaming during the birth process. When these aggressions happen, it puts birthers in the very difficult situation of having to choose between the emotional labour of calling out staff members and risking comprised care, and the emotional labour of staying silent and feeling uncomfortable during an experience where trust and safety are critical.

Nursing Trauma: Nursing a baby can be really hard. Parents who expect to nurse but run into barriers often describe the experience as traumatic. It can be frightening to have your baby/babies lose weight rapidly, get very dehydrated, or grow so hungry that they cry a lot. Parents often describe the early days of nursing as traumatic when it involves nipple mutilation, pain from clogged ducts and mastitis, tongue-tie releases, round-the-clock pumping, and tube, finger, or cup feeding. This is often escalated by worry for their baby, internalized feelings of failure, externalized pressure to nurse, and general confusion about where to get accurate information because there’s so much contradictory advice out there. And even parents who eventually manage to nurse exclusively can continue to be traumatized from those initial challenges.

Loss Trauma: Failed fertility transfer, miscarriage, chemical pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, or death shortly after birth are often recognized as traumatic and grief-filled experiences, because they are devastating, painful, unfair experiences by their nature. But there are aspects of loss that can escalate these already-traumatized feelings. The first is that inexperienced staff are sometimes so uncomfortable giving the news that they avoid using the words “Your baby has died” and use softer, confusing language such as “I can’t find the heartbeat,” leaving parents to try to figure out what’s happening on their own. Second-trimester loss in the case of a missed miscarriage can be particularly painful because parents may not be offered a birth and death certificate, so they can’t bury or legally name their baby, which can feel invalidating or leave parents feeling like their experience was minimized or erased. And if a baby dies after being released from the hospital, there is generally a police investigation, which escalates the trauma.

Pregnant people who choose to terminate a pregnancy can also experience loss trauma. This is especially true for wanted pregnancies that aren’t viable, but also sometimes for unwanted pregnancies, because the decision to terminate an unwanted pregnancy is not always easy. Often there’s a gap between the decision and the procedure itself, which can be particularly painful for birthers who are carrying a dead fetus. Generally, those seeking termination are not allowed to take a support person into the room with them, so they’re expected to cope on their own or with the support of an unknown medical professional. Every client that I’ve supported as they make choices about termination has been afraid that they’ll encounter protesters showing misleading and intentionally traumatic visuals in an effort to shame and disturb them, or that they’ll be refused by medical staff at the hospital.

One of the issues with birth and reproductive trauma is that there’s some confusion about who gets to name and define it as trauma. In my years as a doula, I noticed that everyone interprets the birth through their own lens. The birth parent might have one narrative, which is different from mine or the midwife’s, which could be different again from their partner’s, with only some people who attended the birth feeling traumatized by the experience. It’s not uncommon for those with birth or reproductive trauma to struggle with flashbacks or intrusive thoughts, to ruminate or think obsessively about the birth, to avoid anything that could remind them of the birth, to have panic attacks, to have trouble sleeping, to disassociate, or to find themselves stuck in a hyper- or hypo-aroused state. Birth and reproductive trauma can be debilitating, which is why it’s so important to find support and why it’s important that we seek to understand the experience of birthers who feel traumatized before we seek to diagnose.

While psychological research in this area suggests that birthers should have the right to define their birth as traumatic or not, not everyone who self-describes a traumatic birth will meet clinical criteria of PTSD according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).12 As Grynpas suggests, the challenge is that the word trauma is used both colloquially (“I was traumatized by watching that scary movie!”) and clinically, which some refer to as a brain injury or nervous system injury, and often people who talk about their traumatic birth experience colloquially are trying to express the extent of their grief and disappointment with what happened at their birth. But some people feel as though their experience is invalidated by only focusing on the clinical definition, and this can even prevent them from accessing funded care.

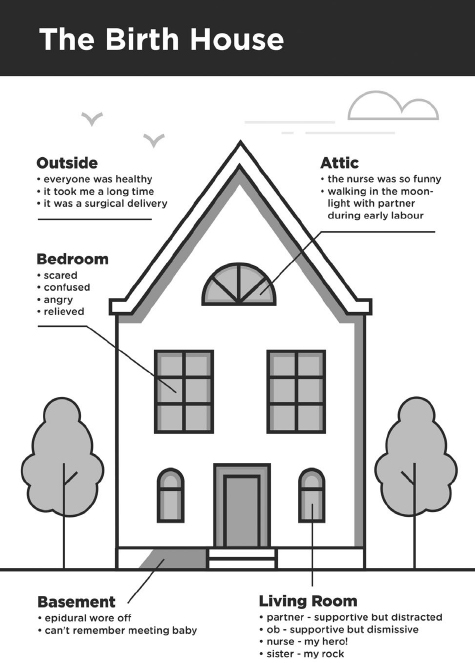

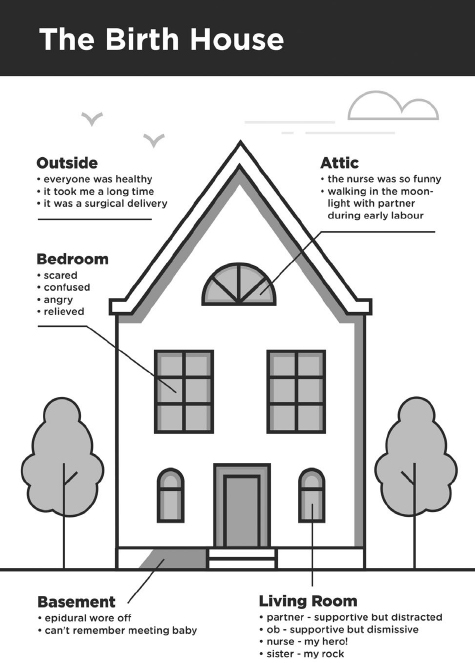

There are several types of therapy that are designed to help you process traumatic memories and events, such as sensory motor therapy, brain spotting, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), or expressive arts therapy. These therapies require that you work with a therapist trained in that specific area, but there’s one tool I can share with you that I use with clients to help begin processing their birth stories, called the Birth House. If it’s too triggering for you think about your birth, I suggest finding a trauma-aware specialist in your area and skip the Birth House exercise.

If you can tolerate writing about your birth, then the Birth House can be quite valuable. That’s true even for people who didn’t have a traumatic birth, because giving birth is intense, and I personally believe that all birth stories need to be processed. You can use this tool to help you process the birth itself or even other events related to reproduction. You also don’t need to be the birther in order to use it.

Start by drawing a picture of a house. Add as much detail as you like, but I’d like you to sketch in a few rooms in particular. You can see an example on page 73.

First, draw the outside of the house. Allow this to represent what other people would say about your birth, and write down what their words might be. What happened? Who was there? What was the order of events?

Now label the living room in the house. The living room is generally the room that we have guests in, just like you may have had guests at your birth. You likely have feelings about the roles that each of those guests played, including partners, medical staff, doulas, family, or friends. Jot down the role that each person played and how you felt about them. You might feel grateful, disappointed, or angry, or a combination of many feelings. Make a note of anything that you wish you could say to each person.

Next, label a bedroom in the upstairs part of the house. Your bedroom is a private place where not many guests are allowed. It is your place of refuge, reflection, and intimacy. Spend some time writing about how you feel about the birth, and any beliefs you have about yourself as a result. These could be positive, negative, or neutral. The goal isn’t to change your inner narrative, but to reflect on the impact the birth has had on you.

Identify a basement next. The basement is a common place where we dump things we don’t need or things that we don’t want to clutter up our house. Often basements can be creepy and uncomfortable. What part of your birth do you not want to think about or want others to know about? What do you wish you could pack up and never talk about again? Or what parts are so scary that they’re hard to remember? Write about these in the basement.

Finally, label the attic. Attics are the place where we store the things that are important, and that we want to protect. It’s also the place where light tends to sneak in through cracks. What parts of the birth do you hold dear? What do you remember fondly? Put those in the attic.

I use the Birth House exercise with my clients to help them see their birth from a variety of different angles. As counsellor Kim Thomas says, when we retell a traumatic birth story, it can feel as though we are in a dark room, shining a flashlight on the worst parts of the experience. The goal here is to turn the lights on and see the full story. While things may have felt chaotic when you arrived at the hospital, it can be very helpful to remember the first hours when you were at home and supported by your partner, which may have been quite lovely. There is no need to turn it into a positive story, but creating a complete, honest narrative helps you begin to integrate how you feel about the entire experience and consider future actions you might take to lay it to rest.

Another thing that makes it difficult to process your birth experience is sleep deprivation — it’s hard to process anything in the absence of sleep. And lack of sleep is the number-one complaint of new parents, as it affects every single aspect of their lives. The next chapter discusses the impact of sleep on postpartum mood.