Chapter 10

The Fang of Orm

The Thousand Years War, so called because a former ruler of Gelnians—King Systole—had vowed that his people would fight for a thousand years rather than submit to the rule of the Grand Megak of Tarmish, was in its ninth year when the War of the Lance superseded it.

Dragons had ruled the skies through those dark times, and great armies had swept through every land—armies of humans, armies of elves, armies of dwarves and armies that were difficult to classify. Some in each land were followers of the Highlords and their dragons, recruited to supplement the draconian armies of the goddess Takhisis. But others had arisen in every land to combat the legions of lizardlike creatures that were the shock troops of the evil goddess. It had been a time of mighty battles, of starvation and desperation, a time fraught with great magic and devastation. And it had gone on for years.

But finally it was over. Wandering skalds and warbling bards proclaimed that the Dark Queen had retreated in defeat, had turned her back on the world she had ruined, and though there still were dragons here and there, no longer were they directed toward a common cause.

There came years of turmoil, times when empires arose and fell like mullet jumping from a stream. Hordes of homeless, rootless refugees had swarmed across the lands, and nothing was safe, anywhere. The wild, fanatic hordes of yesterday were replaced by a new breed of adventurers—mercenary warriors at the bidding of any who could afford their wages.

Organized insanity across a ravaged world replaced the random insanity of the turmoil. Now the war was a different kind of war. Both Tarmish and Gelnia had new rulers, and these were people unlike the kings and megaks of old. Somehow, during the chaos following the War of the Lance, both dominions had been infiltrated and claimed by outsiders. In both realms the old dynasties still were evident, but now they were no more than puppets.

Dominated now by a mysterious figure known as Lord Vulpin, the Tarmites had resurrected their threadbare Grand Megak from a foul cellar somewhere and put him back on his throne at Tarmish. The Gelnians, too, had a different ruler. Chatara Kral, a woman of mysterious background who had come with a private army of mercenary soldiers, named herself as regent over Gelnia. One thing remained as it had been, though. Tarmish and Gelnia, under whatever rule, refused to tolerate the existence of the other. The Vale of Sunder was back to business as usual: all-out war.

The origins of the disagreement between the city-state of Tarmish and the land surrounding it were lost in antiquity, but not the passions of it. Few wanderers through this land could tell a Tarmite from a Gelnian. They were the same kind of humans, cut from the same cloth. They spoke the same idioms, worshipped by the same rituals and claimed the same ancient ancestry, though each denied that the other had any such claim. Many were, indeed, related to one another by blood and marriage. Yet they were the bitterest of enemies.

Gelnian and Tarmite, neither would tolerate the other. And, as always, the flames of hatred were fanned by those who stood to gain. Always, in every land, there were those to whom conflict was the path to power and riches. Behind the tottering Grand Megak of Tarmish, like a towering dark shadow, stood Lord Vulpin, his hand in every intrigue, his thumb on every pulse, dreams of empire swirling in his cunning mind. And among the Gelnians, it was Chatara Kral who guided destinies now, as ward-regent to the infant Prince Quarls.

The origins of Vulpin and Chatara Kral were obscure. There were whispers in surrounding lands that the two were in fact brother and sister—the spawn of the evil Lord Verminaard, a Dragon Highlord of the recent War of the Lance. But in their own domains, nobody knew or dared to question where either of them came from or why they were here. It was enough, for most, that they spoke to the ancient hatreds of the region.

Now they faced off for control of all of Sunder. Vulpin stood in his tower overlooking the fortress of Tarmish, Chatara Kral amassed armies of Gelnians and mercenaries in the hills around. For months the Vale had seemed to hold its breath, awaiting the clash.

It was a standoff, a time of waiting. But Vulpin had made use of the time. Useful artifacts remained from the mighty war, and he had sent agents in search of such things. Even now, one such relic was on its way to him … if one called Clonogh could spirit it through the Gelnian blockade.

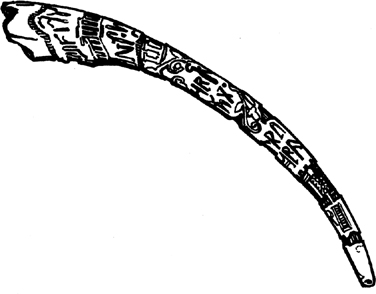

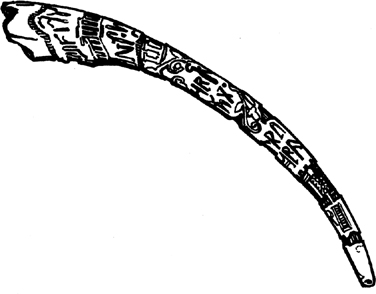

Among the secret documents of Krynn was a collection of scrolls, some very ancient, concerning a relic sometimes called Viperis, sometimes Wishmaker, and most often the Fang of Orm.

The scrolls once rested in the tombs of Istar, but somehow survived the Cataclysm and found their way to Neraka, and thence to Palanthas. Their last known resting place, prior to the War of the Lance, was the stone vault of the wizard Karathis, who sought immortality through the vesting of arcane powers upon the ambitious in exchange for portions of their lives.

The scrolls disappeared when Karathis was murdered by one of his customers, but their contents were known to the wizard’s acolytes. They told of the Fang of Orm.

They say the fang grants wishes, but only for the truly innocent. And in granting wishes, the fang brings doom to its holder.

They say the Fang of Orm is not dead, but only asleep, and there remains a bond between the fang and its original possessor. When awakened, the relic still sends its ancient signal, and on some inconceivable plane of reality the creature from which it was torn still seeks it.

* * * * *

The man called Graywing crept silently from boulder to cleft, approaching the naked granite sheer that was the top of a shattered ridge. His senses were pitched to the windy crest, his eyes missing nothing as he moved, his ears sorting out the whispers of wandering wind and the calls of hunting birds soaring high above, his nostrils searching for any slightest scent that might betray enemy presence.

Such scrutiny was nothing new to Graywing. For most of his life, it seemed, daily survival had depended upon knowing who or what was near, before who or what discovered him. Descendant of Cobar plainsmen, he had come of age fighting Empiremen on the plains east of the Kharolis, then followed Falcon Whitefeather and the elf Pirouenne in their assault on Fe-Tateen.

Partly through his skill in guerilla combat, but mostly, he felt, through sheer luck, Graywing had become a captain of assault forces with the Palanthan Armies at Throt-Akaan.

Then that war, which settled many disputes in the northern greatlands, had ended. And now Graywing, like thousands of others whose entire experience was in battle, found himself hiring out as a lone mercenary. Hundreds of little wars had sprung up in the shambles of the great conflict, and there was plenty of employment. Men he had known for years now met on a hundred fields of battle, trying to kill one another for the wages paid by petty realms.

At least, he thought, I still can choose my jobs.

Somehow, the idea of doing battle for wages had never appealed to him. So he lived these days, as now, hiring out as guide and bodyguard for travelers.

At the crest of the ridge he crept to the lip of a stone outcrop and looked beyond. A wide, fertile valley lay before him, a valley that should be lush with ripening fields and rich orchards. Instead, as far as he could see along the lower slopes there were wisps of smoke—smoke from hundreds of separate campfires where little groups of armed men sat idle, waiting for orders. Beyond, in the distance, a squat fortress stood on a hill, and above it, too, hung the smoke of waiting.

Graywing’s thick, corn silk beard twitched as his lip curled in a sneer. Blood would flow in this valley soon, and most of it would be the blood of fighters not personally involved in whatever conflict was growing here. Those who would bleed and die were mostly just men like himself, veterans with no skill but arms and no trade but war, men who would die for a few coins.

For long moments he studied the scene, practiced eyes seeking a route through the cordon of warriors. Then he backed out of sight, turned and looked to his own back trail. Again a sneer of distaste curled his lip. His employer was part of all this, of course. Clonogh was some sort of courier, he gathered. His destination was that fortress out there, and Graywing’s job was to take him, and whatever secret thing he carried, there safely.

He didn’t want to know any more than that about it, but he would be glad when it was done. Something about the courier made Graywing feel a little clammy. Whether it was the man’s furtive manner—like a ferret slinking toward its prey, never straight forward but always at a deceptive angle—or possibly in the way the man’s face seemed always hidden by the cowl of his dark cloak, or possibly the edgy, nervous way he guarded that leather pouch slung to his shoulder, Graywing didn’t know.

It was as though Clonogh were a relic of another time—a lost, insane age when mages were everywhere and sorcery ran rampant on Krynn. Graywing didn’t know whether Clonogh might be a secret sorcerer, but there was a quality about the man that raised his hackles.

He simply did not care for Clonogh. He would be glad to be rid of him when this journey was done.

Now, carefully, he made his way back to the crevice where he had left his employer. “There is a route through the cordon,” he said, “but it won’t be easy. There are sentries, and a dozen places where ambush would be easy. Suppose we have to fight? How are you armed?”

“You are armed,” the hooded figure indicated the long sword at Graywing’s shoulder. “I pay you for your skills, and for your sword as well,” Clonogh said, his face a shadow within shadows. “You are my guide, and my protection.”

“Fine,” Graywing rasped. “If we run into trouble, it’s all up to me. Is that how it is?”

“I pay you well enough,” Clonogh purred. He picked up his walking stick—a fine, short staff of intricately carved ivory, slightly curved and delicately tapered—and got to his feet, hugging his leather pouch close to his side with a protective elbow. “I expect you to do your job.”