SEVEN

The Cooperative Ideal

Beneficence, mutual aid, and charity are at the heart of the Masonic traditions, in all forms of the Masonic obedience and nations. These values assume a particular acuteness in the black community, however, throughout the time spanning the creation of the Prince Hall Lodges, then with even greater intensity after the Civil War, and throughout the twentieth century. At the end of the Civil War everything needed to be constructed with respect to social protections. The Prince Hall Masons were savvy enough to then take a place in the field of volunteer organizations to promote mutual aid before encouraging blacks to enter the business world.

From 1792, Prince Hall had emphasized the charitable obligations of Freemasons. This notion of obligation is not confined only to Freemasons, however; quite the contrary. In 1797 he stressed the duty of solidarity with the whole of humanity, without even giving the black community any special privileges, as his descendants would do.

We see how necessary it is to have a fellow feeling for our distressed brethren of the human race, in their troubles, both spiritual and temporal. How refreshing it is to a sick man, to see his sympathizing friends around his bed, ready to administer all the relief in their power; although they can’t relieve his bodily pain, yet they may ease his mind by good instructions and cheer his heart by their company.1

In 1793, when a yellow fever epidemic struck Philadelphia, Absalom Jones, worshipful master of the Prince Hall Lodge, mobilized his brothers as well as those from other lodges to give aid to the sick.2

It was, however, during the years of reconstruction following the Civil War that a large number of mutual-aid societies emerged, either directly connected with the Prince Hall Lodges or very close to them. The Odd Fellows, the Knights of Pythias, and the Knights of Tabor grew stronger during this time, as did two women’s organizations: the Order of the Eastern Star and the Calanthe Sisters.3

In the eighteenth century the members of the first English lodges had the custom of attending the plays performed at the famous London theaters of Drury Lane in particular, giving them financial backing and writing prologues and epilogues in honor of Freemasonry that would be read on stage.

At the beginning of the twentieth century the Prince Hall Masons also had taken on the task of encouraging cultural activities, often for charitable ends. The brothers of the Carthaginian Lodge n° 47 organized variety shows for the purpose of collecting funds to support their needy members. In 1905 the lodge organized a ball in Brooklyn. In 1909, and again in 1910, the brothers, but also some profanes as well, most likely, were invited “to a ball and vaudeville show” by these “ladies,” probably the wives of Masons, that took place in Brooklyn, then a noted black suburb of New York, all for the “profit of the lodge.”4

Mutual-Aid Societies

The Odd Fellows appeared before the Civil War. It was originally a “friendly society” created in England during the eighteenth century. These numerous societies of mutual aid are intended to provide assistance to members and their families when they are struck by death or illness. The existence of these societies, in contrast to that of the first unions, was enthusiastically supported by the British authorities. They openly displayed their respect for the established order and religious morality. Contrary to all other associations in the United Kingdom, they were the only ones, other than the Masonic lodges, who were granted permission to hold meetings after 1795.*21

The first American Odd Fellows lodge was established in Baltimore in 1819. The first black Odd Fellows lodge, the Philomathean Lodge n° 646, was created in New York in 1843 on the initiative of Peter Ogden, who obtained a charter from his own lodge in Liverpool. Ogden, a black steward aboard a British vessel, advised the New Yorkers to directly solicit his English lodge rather than the white American Odd Fellow lodges.

In 1847 there were twenty-two Odd Fellow lodges in the United States, only one of which was black. It so happens that the Odd Fellows enjoyed enormous success in the black community, for the number of black American lodges had climbed to around fifty by 1863.5 By 1893 the black organization of Odd Fellows claimed some two hundred thousand members. These Odd Fellows were placed under the control of their high officers, who met in their Philadelphia headquarters in a fairly autonomous fashion, it seems, with respect to the white Odd Fellows lodges.

The Odd Fellows supplied aid primarily to their members and their families, but, as much as their means would permit them, they were open to take requests from outside the order into consideration. They defined themselves as a “vast mutual-aid society.”6 The members paid dues and, in exchange, received assurance for basic medical coverage. The family would receive a precise sum on a member’s death. The members also received financial support while looking for employment. However, the society denied it was only useful on a material level and claimed it was working toward the perfection of its members.

Those who speak of our Order as merely a sick society, betray an utter ignorance of the institution they undertake to criticize. . . . The object of this Order is to elevate the whole man, its provisions have reference to his intellectual, moral, and physical capabilities, it influences every circumstance of life, and it is calculated to modify the relations of society, both morally and politically. Its influence as a political safeguard cannot be overestimated.7

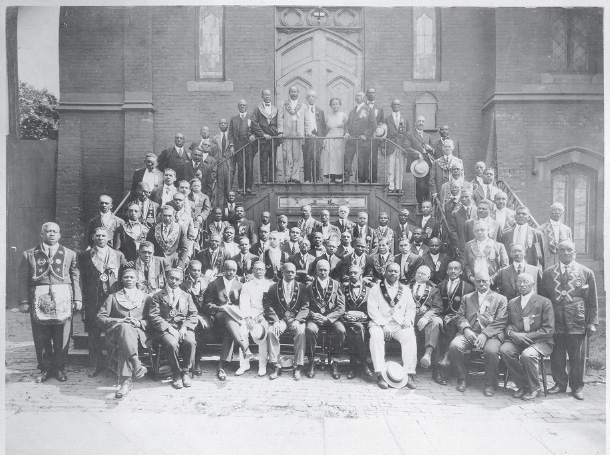

Fig. 7.1. District Grand Lodge no 2, Grand United Order of Odd Fellows, Albany, August 2, 1921 (courtesy of the Chancellor Robert R. Livingston Masonic Library)

The black wing of the Odd Fellows association, which seeks to give social protection to its members, is also meant to protect their morality and thereby perform a favor for the political authorities, exactly like the friendly societies of eighteenth-century Great Britain. The black members of the Odd Fellows therefore undertake on their behalf the structure and goals of the white organization. The exact nature of the relations between the black and white lodges remains a mystery. It seems that the black American association of the Odd Fellows had an entirely autonomous means of functioning. There was also a women’s branch of this order: the Grand Household of Ruth.8

No formal ties exist between the Prince Hall Masons and the Odd Fellows. However, both organizations had many members in common. For example, James Needham, who founded Unity Lodge n° 711 and the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows of Philadelphia, was also an influential member of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania. He was involved in the battle for civil rights as treasurer of the Pennsylvania State Equal Rights League.9 Similarly, according to the 1949 annals of the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of South Carolina, S. C. Moore was both a member of this grand lodge and grand master of this state’s Odd Fellows.10

Fig. 7.2. Grand Master John P. Scott, an educator whose name graces a Harrisburg elementary school, presided at a ceremony with several members of the Grand Chapter of Odd Fellows by the First Stone Church, Wesley Union AME Zion, situated at the corner of South and Tanner Streets, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, Sunday, October 18, 1914. Tanner Street was populated by a large number of black Americans who participated in the Underground Railroad in the nineteenth century. (photo courtesy of John Slifko)

Odd Fellows meet in a lodge, following the Masonic model, and practice a ritual. They even claim to be more democratic than the Masons. This is how Charles Brooks, grand secretary of the order, put it in the preamble to his official history of the Odd Fellows.

The Order of Odd Fellows is truly a Friendly Society, and always has been. Its fundamental principles and distinguishing characteristics are as different from those of Masonry as chalk is from cheese. The rich and poor, the high and low, the Prince and Peasant, men of every rank and station in life are and always have been admitted to odd Fellowship on equal footing. Not so with Freemasonry.11

This would make Odd Fellows somewhat the Freemasonry of the poor. This argument is quite significant. While Prince Hall Freemasonry was essentially perceived—and seemingly rightfully so—as a bourgeois institution, the Odd Fellows claimed a more popular recruitment. Nevertheless, the ties between the Prince Hall Grand Lodges and those of the Odd Fellows are quite real.

The Mechanics play a role providing mutual aid that is quite similar to that of the Odd Fellows. Numerous Prince Hall Freemasons are still members of this order today, in both the United States and the English-speaking regions of the Caribbean. In his history of Celestial Lodge n° 3 of New York, Harry A. Williamson notes that the worshipful master of this lodge in 1908 was able to hold in his own hands the original charter of the first Prince Hall Lodge during a gathering of Masons at Mechanics Hall in Worcester, Massachusetts. Williamson explicitly states that the local of the Mechanics was placed at the disposal of the Prince Hall Freemasons.12 When one is aware of the symbolic importance of the charter granted to the African Lodge of Boston, we can measure the full importance of this event in the life of this New York lodge.

Charity or Mutual Aid?

Outside of the Odd Fellows and the Mechanics, many mutual-aid societies existed in a more or less temporary form in the black community. While naturally not all of them were connected to Freemasonry, the Prince Hall Masons did play a major role in a large number of them, either by founding autonomous societies modeled on the Masonic structure, with their own rituals, or by combining with already existing societies. The notion of mutual aid prevailed over that of charity, despite the opposition of some Masons who preferred the idea of spontaneous benevolence to that of mutual aid of an obligatory nature.13

Several Prince Hall lodges equipped themselves with bodies intended to provide direct assistance to their members or to those of the lodges in their region. For example, the Sumner Lodge of Springfield, Massachusetts, created the New England Masonic Mutual Relief Association, with an eye toward assisting the “indigent widows and orphans in our midst.” The annals of the Massachusetts Grand Lodge make mention of this in the minutes for 1870.14 During this same time the Celestial Lodge n° 3 created several mutual-aid societies: the Hiram Masonic Relief Association, the Masonic Mutual Relief Society (for a similar purpose), and the Masonic Memorial Burial Fund, to cover funeral expenses.*22 15

The Hiram Masonic Relief Association was active from 1888 until the mid-twentieth century.16 Furthermore, the lodge stepped in to provide aid for the society at large, and not simply to give assistance to its own members. For example, in 1923 it donated ten dollars in assistance to Japanese earthquake victims and awarded an unspecified amount to the Citizens’ Christmas Cheer Club for Widows and Orphans to give these individuals the means to celebrate Christmas.17 Two years later this same lodge gave a ten-dollar grant to a day-care center maintained by a neighborhood Catholic church. In 1928 it offered financial support to a coed summer camp. In 1937 a donation was given to help the victims of flooding in the western United States.18

All these actions prompted commentary by Williamson: in his opinion the lodge had acted too generously on some occasions and sometimes lacked discernment. It had given assistance to various organizations that had no Masonic connections and even to a body that was under the jurisdiction of the Catholic Church! Williamson found accord here with the viewpoint of white American Masons who advocated the separation of church and state in the name of religious freedom inscribed in the American Constitution. Lodges should not pledge their faith to any particular church, although they preach religious values themselves. American Masons were particularly critical of the Catholic Church, which ran a large number of private schools. Williamson adopted a point of view that could almost be described as secular when he took offense at the assistance provided to a Catholic day-care center. In addition, he bemoaned the greed of several widows who attempted to shamelessly extort money from the lodge.

These observations offer a clear illustration of the mutual assistance that prevailed in the Prince Hall lodges. Although charity was advocated by almost all Masonic obediences, black Masons preferred to envision benevolence as a form of mutual aid. The brothers decided to lend assistance because they had decided to pay dues and equip their lodges with a specific entity with an eye toward having a minimal level of social protection that would mitigate the state’s lack of support. It was mutual assistance far more than any kind of charity.

Other Masons feared that the Prince Hall lodges would not confine themselves to this role of assistance and would therefore be exposed to adulteration by losing their symbolic, if not to say philosophical, nature. Hence, the thousand precautions erected by George Crawford, author of a small practical manual for Prince Hall Masons, when speaking of mutual-aid societies. He takes pains to distinguish them from Masonic lodges and to show that in no case can they ever serve as a substitute for the lodge.

To a certain extent the difference between the provisions for relieving distress in Mutual Benefit Societies and lodges of Freemasonry is largely one of emphasis. In the one case the “care for the sick and burying the dead” provisions are the main object and fraternal and social features are incidental. On the other hand, in Masonic bodies the fraternal, moral, and social features are primary while for the needy, it is incidental. All of which is to say that help for the brother in need can and must be provided without compromising the great and paramount purposes of the Fraternity.19

The viewpoint expressed by Crawford is certainly quite representative of sentiments held by many of his fellow Masons. His alarm is revealing in any case of the strong tradition of mutual assistance among Prince Hall Masons. Some officials feared that the black obedience would be regarded only as the poor man’s Freemasonry, or at least as a mutual-aid association that was more concerned with charity than symbolism and therefore probably less respectable. Perhaps this attitude can also be explained by a slight complex toward the white American Masonic obediences, which displayed unrelenting scorn for the black lodges.

The Other Forms of Mutual Assistance

Like their white “brothers,” the Prince Hall Freemasons have always made the fields of education and health a priority. I have already mentioned in chapter 5 the scholarships they handed out to students of New York and Barbados. Similar examples are abundant throughout the United States. For the year 1982 alone, the southern jurisdiction of the Prince Hall Scottish Supreme Council gave grants totaling one hundred thousand dollars to black institutions of higher learning.20

The widow and the orphan attracted the attention of the Masons in particular; in the previous section I cited various actions taken by lodges and the associations they put in place to come to the aid of the families of deceased Masons. The same holds true for the elderly. The Prince Hall temple in the heart of Harlem is adjoined today by a retirement home supported by the grand lodge that is intended for Masons and their close relatives. The activities conducted by black grand lodges in the medical field are less spectacular than those of the white grand lodges, for want of financial means, but are significant nonetheless. Blood banks have been set up in several states by Prince Hall lodges; their use is primarily for Masons, but they are also open to the profane.

During the Second World War the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of New York formed a committee that would oversee the provision of material and moral support to Masonic soldiers and their sons, as well as a special fund, the Prince Hall Masonic War Fund. These funds continued to accept contributions after the war in order to provide assistance for the wounded.21 Today, according to Joseph Walkes, the association of the Prince Hall Shrine, which is non-Masonic but operates closely with the Prince Hall Grand Lodges, regularly contributes “thousands of dollars” to the Prince Hall Shrine Health and Medical Research Foundation, formerly known as the Tuberculosis and Cancer Research Foundation. Additionally, annual scholarships of six thousand dollars are regularly awarded to hospitals and institutions of higher learning.22

According to Walkes, scholarships are also awarded to young women who are seventeen to twenty-four years of age to enable them to enroll in the universities of their choice. Can Prince Hall Masons still be accused of sexism?*23

Finally, the Prince Hall Grand Lodges also seek to provide financial assistance to youth through a program that fights against drug use and delinquency.

The Mutual-Aid Banks

In the social sector the most specific and probably most spectacular action taken by the Masons of Prince Hall was certainly the creation of banks modeled on mutual-aid societies. Muraskin cites the particularly ambitious speech of the Alabama grand master who in 1909 bemoaned the fact that Prince Hall Masons confined their social activities to assistance to the ill and contributions to offset funeral expenses, in accordance with the tradition of friendly societies.

The eternal shame of Negro secret societies is that the most they are accomplishing is to take care of the sick and bury the dead. I am of the opinion, that properly managed, through our Masonic lodges, reinforced by other societies, many of which most of us are members, farms could be owned, teachers trained to instruct us, soldiers trained to defend us.23

Obviously these goals were not attained. However, in 1911 the Grand Lodge of Texas founded its own bank, the Fraternal Bank and Trust Company. Individual members and the lodges themselves were encouraged to invest. Each lodge was expected to deposit at least 10 percent of its capital in the bank. The fraternal bank was administered by shareholders and not directly by the grand lodge. In the beginning the Texas Masons turned for assistance to the Odd Fellows and the Knights of Pythias, who bought 2,500 of the 5,000 shares. In 1930 the Grand Lodge of Texas was strong enough to take possession of the majority of shares and to set itself up as a lending body for black Masons. The bank was still in existence in 1953. The Grand Lodge of California was not able to follow the example of Texas but did create a loan organization through the Prince Hall Credit Union n° 1 in San Diego. It also financially supported an association to promote construction, the Liberty Building and Loan Association. Meanwhile, the Grand Lodge of Georgia encouraged all its members to invest in black banks as a priority.24

The goal of all these banking operations was to promote black companies and help the brothers make investments in the business world. Of course, the mortality rate for black businesses was particularly high, as noted by Muraskin, who does not conceal his admiration for the battle waged by the Prince Hall Lodges to assist them. Consulting the Who’s Who in Colored America from the years 1933 to 1937, he drew up a list of the Prince Hall Masons who had found success in the business world. Among those he mentions are W. W. Allen, grand master of Maryland and sovereign grand commander of the Scottish Rite Masons, Southern chapter, who headed the Southern Life Insurance Company of Baltimore; and John Webb, grand master of Mississippi, director of the Universal Life Insurance Company of Memphis and the president and treasurer of another insurance company in Arkansas.

Other examples Muraskin gives include that of Grand Master Theodore Moss of California, who owned the Independent Plumbing Works of California and organized a business club for blacks, the Modern Order of Bucks. According to Muraskin, 80 percent of the names listed in the black Who’s Who of this time were members of Prince Hall.25 This percentage testifies to the role played by Prince Hall Masonry in the advancement of the black middle class. The question can be raised, Did Masons attempt a formal translation of the tontine process, the traditional way capital was mobilized in African-style societies, which still survives in the Caribbean, as shown by the Haitian sou-sou?

The Difficult Relationships with White Organizations

The relationships between the mutual-aid or benevolent societies reflected the racism that, with few exceptions, raged in the various Masonic obediences. This will be the subject of part 4 of this book. I will only cite two examples here: that of the Odd Fellows, a mutual-aid society, and that of the Shriners, a charitable organization. These two organizations existed in white and black associations, but with no intermingling.

The history of the creation of the first black lodges of the Odd Fellows is significant. Boston women, most likely of the upper middle class, had stepped in unsuccessfully and encountered great difficulty in working with the city authorities. They had requested that blacks, in order to prepare the creation of an Odd Fellows lodge, be allowed to meet at Faneuil Hall, a shrine of the American Revolution and thus a symbol of freedom, but only freedom for whites. It so happens that it was the members of this mutual-aid society—until that time all white—who were trying to halt the movement of the association into the black community. When the black sailor Peter Ogden, who had long lived in Great Britain, tried to arrange a meeting with the New York Odd Fellow members, he ran into a wall. He recounts that incident.

On my arrival in New York, I wrote to them, informing them of my arrival and appointment, also my readiness to meet them for the purpose of effecting a union between them and our lodge. I felt disposed to make every concession that could consistently be done; in about four days a man called on board my ship and enquired for Peter Ogden. I informed him it was my name; he said I was not the person he was looking for. I told him there was no other person of that name on any of the ships; however he left without saying anymore. In four or five days I received an answer to my letter, declining an interview on account of what do you think? On account of color.26

The second example of the strained relations between the two American communities is that of the benevolent society known as the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, or simply the Shriners. Although this organization is not, strictly speaking, Masonic, the only individuals eligible to join it are Masons who have attained the 32nd degree of the high Scottish grades or the highest degree of the York Rite, that of Knights Templar. It is easy to see that this charitable organization is also, or especially, an honorific site where the highest grades of the Masonic Order can enjoy meeting each other, whether they come from the York Rite or the Scottish Rite.

While the plurality of rites is recognized, the same has not always been true for ethnic origins—quite the contrary. The first Shriners’ association was created in New York in 1872 by white Masons. Blacks created a similar body for the first time in Chicago in 1893. Several Shriners’ associations appeared in various states, separate, of course, founded by white and black Masons. In 1918 the white Shriners of Texas filed a suit on the pretext that the black Shriners were using the same name as theirs. The affair generated a nationwide controversy between white Shriners and their black counterparts. The Texas court found in favor of the white Shriners and forbade blacks from using the same name, which they were considered to have usurped.27 There are no grounds to be surprised by this verdict, which is an illustration of the visceral racism of the Texans of that era. Unfortunately, the Texas Masons were not figures of exception on this occasion.

The history of the mutual-aid and benevolent associations is liberally sprinkled with racist incidents similar to the one described above.