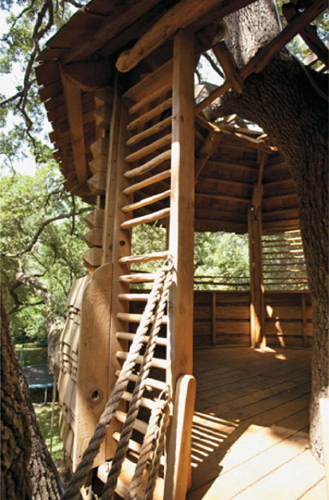

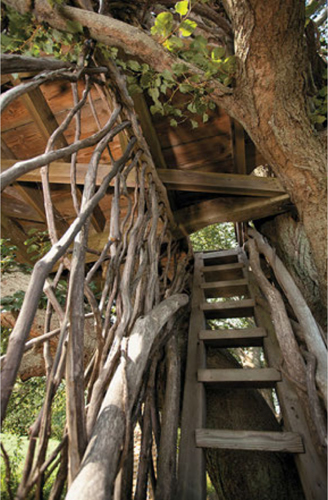

A secondary tree, independent of the main structure, is used to bring people up from a lower deck to the treehouse above. Critical to its design is its flexibility. Note how the stair landing is able to slide as the trees move independently of each other.

The Majestree, at 47 feet above the ground, is an excellent example of a single-tree design that incorporates both beam-and-brace and cable support systems.

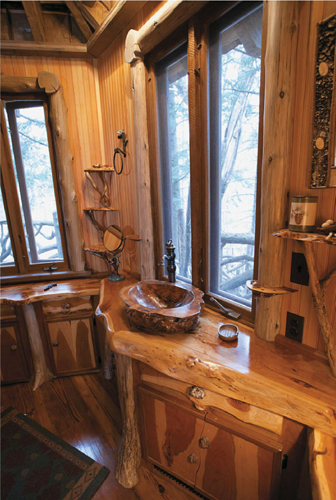

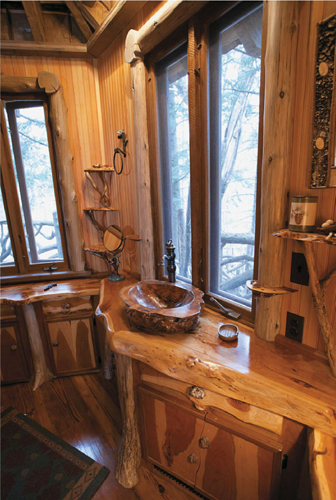

A bathroom so high in the trees is quite a luxury. Note the on-demand water heater above the toilet tank.

Plumbing a treehouse is similiar to plumbing a regular house. Pipes flex with the tree.

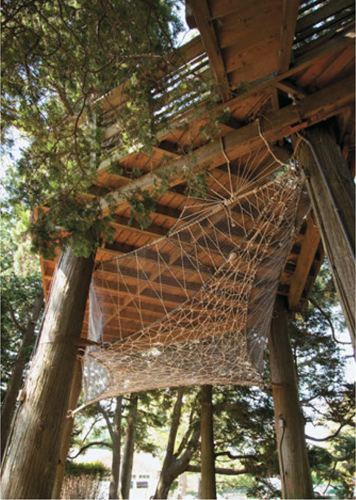

Michael Garnier demonstrates his style of the reverse triangle used to support heavy loads when there is an obstruction above

and a less expensive suspender cannot be installed.

Majestree, Out’n’About

Takilma, Oregon

It would only be fair to start this tour at Michael Garnier’s “treesort,” Out’n’About, in Takilma, Oregon.

Michael Garnier has taught me more about treehouses than anyone else. I met him in 1992, and he has been teaching me and countless others ever since. Schooling might be the more appropriate term in my case, as he has a quick wit and even quicker hands. I tend to be his foil during our annual World Treehouse Association conference gatherings, and Michael is a consummate showman. He is also whip smart, a superb dancer, and deadly serious about his treehouse craft.

Michael was an inspiration behind building our own bed-and-breakfast at Treehouse Point. He worked with Josephine County for eight years before they finally allowed his treesort to legally exist. I watched his struggles as he demonstrated the integrity of his structures, and treehouse builders will always be in his debt for the difficult trailblazing that he has done.

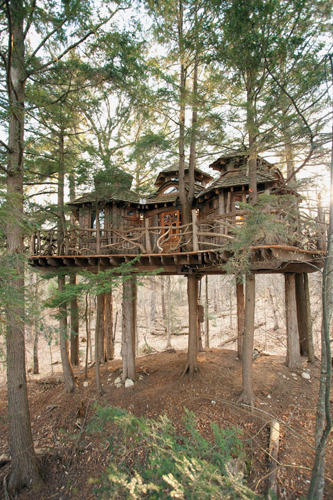

The latest addition to his eighteen-unit treesort is the Majestree (if you go to his website, www.treehouses.com, you will see that he plays with the word tree a lot). It is his highest residence and can fit up to six people comfortably. It has a full bathroom with toilet, sink, and shower, a queen-size bed in the main room, two double beds in the loft with an additional daybed, a compact kitchenette, and a porch with a spiral staircase to a private deck below. This magnificent abode is 47 feet up in a Douglas fir with some extraordinary custom woodwork inside and out.

The multistory structure, complete with a wraparound deck, lights up a Pacific Northwest forest.

Santuario de Basurto

Woodinville, Washington

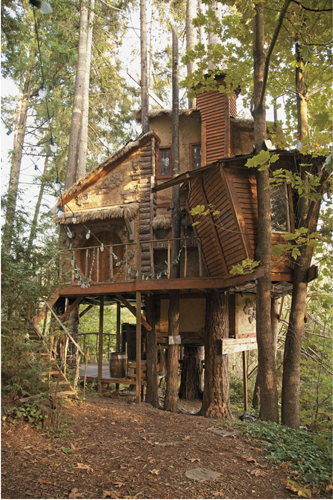

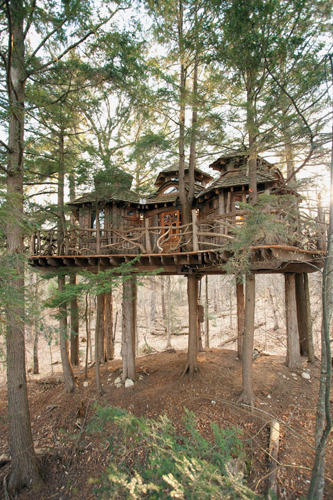

This stunning treehouse was born of a desire to build a children’s tree fort. The project began with modest but lofty ideas. It soon expanded to encompass seven trees and new goals: The treehouse should be comfortable for adults as well as for kids, and materials should be sourced locally, repurposed whenever possible, and green. Thankfully, the Seattle area has many architectural salvage yards! Windows, doors, and flooring were all given second lives. Local western red cedar and Douglas fir were used whenever possible.

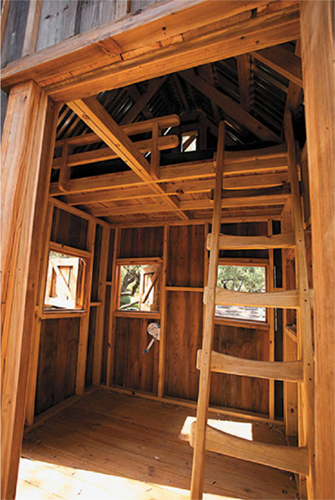

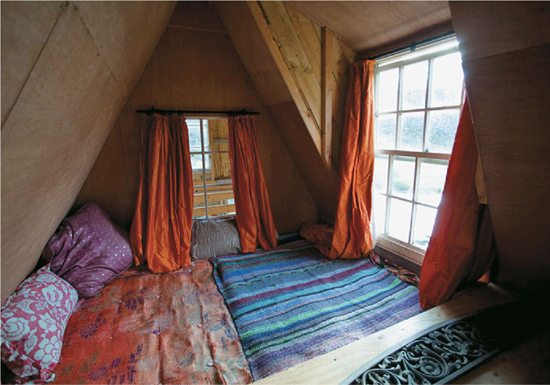

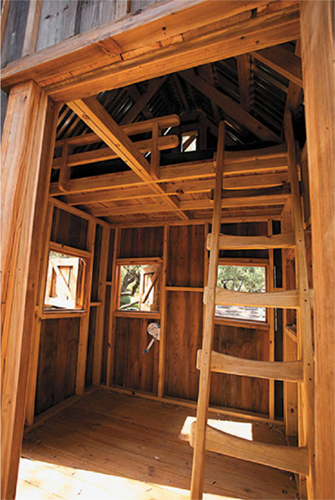

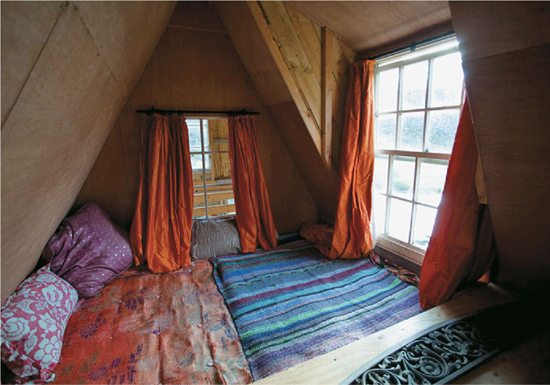

So the fort became a spectacular treehouse, which was built by David Gieson. The wraparound deck allows one to literally stroll about high in the forest. Views of the trees can be had from every angle. Indoors, the first-floor ceiling is high enough to make the room feel large and comfortable. Up the ship’s ladder, the loft is the counterpoint to the main room: A low ceiling and foam bedding make for a very cozy, intimate atmosphere. Naps abound here. And atop all of this sits the cupola, from which one can see 360 degrees around the forest. Thoughtful lighting inside and out makes this treehouse a pleasure to be in and around.

Kids run laps around the deck and slide down the fire pole to the swings below. They run back up the stairs and climb to the cupola, spying down on their friends. When the kids tire, the adults make their way to this treehouse, open a bottle of rum, and sit quietly talking on the back porch, their words mingling with the songs of birds. Santuario de Basurto translates as “Sanctuary in the Middle of the Forest.”

The treehouse stands tall in a mature Douglas fir forest. Its western red cedar railings are remnants from

a huge treehouse job at Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania.

Intricate trim work and thoughtful lighting create a warm and inviting wooden retreat.

Gieson’s attention to detail is apparent in the interior finish work and exquisite furnishings.

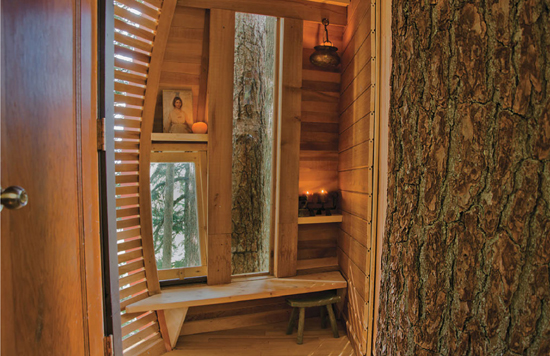

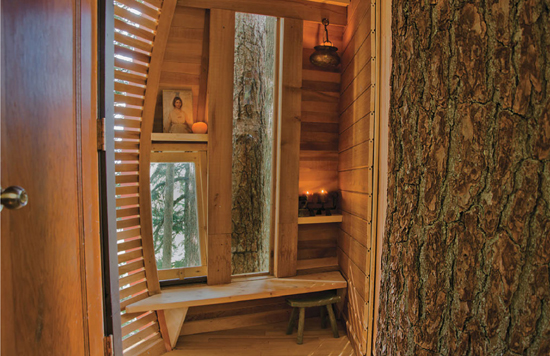

Built-in shelving and windows cover every inch of this Arts and Crafts treehouse. It’s particularly nice to see one of the support trees featured so prominently.

A cozy sleeping loft leads by a ship’s ladder to the lookout, which has a 360-degree view of the surrounding forest.

Victor Brothers Treehouse

Western Washington

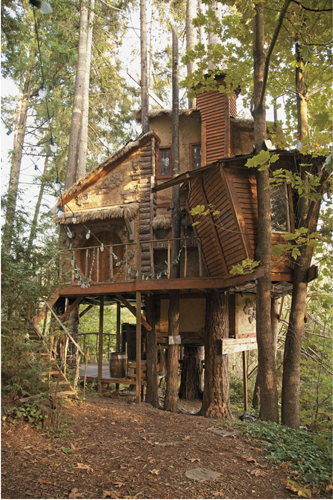

The first effort by the brothers Victor caught fire. The second—built in the same place—is indelibly printed in my mind as the most extraordinary and ambitious high school project ever realized. Most large-scale undertakings remain in the minds of cash-poor and unskilled teenagers. The brothers Victor, however, overcame the odds.

I have come to know these gentlemen well over the last several years. Michael, Paul, and Daniel are now in their twenties. Their father came to Treehouse Point to tell me of his sons’ exploits, and when I arrived at their house—only ten minutes from my own—they had a Canon 5D camera trained on me the entire time. As it turned out, the brothers are deep into the digital world, and after I had them help me document our project at the WC Ranch, they decided it was time for a treehouse app for smartphones and tablets. I didn’t know what that meant at the time, but I do now. True to form, they did another extraordinary job. It’s called Treehouses of the Pacific Northwest. Please look it up!

Maple, Douglas fir, and hemlock trees support a wildly creative second effort by the three Victor brothers.

The first treehouse that they built together at this location burned down.

The hobbit door is surrounded by real rocks and masonry. It is holding up well despite its considerable weight and the inevitable movement from swaying trees.

The music room is reminiscent of the stern of an old sailing ship.

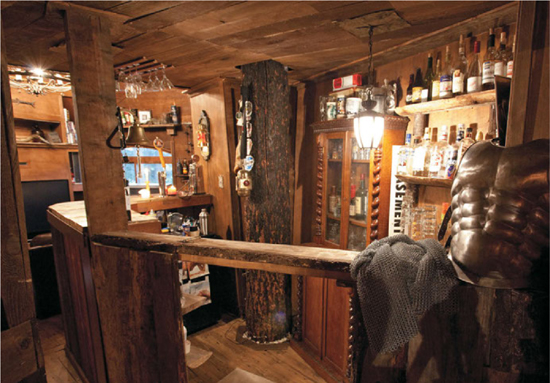

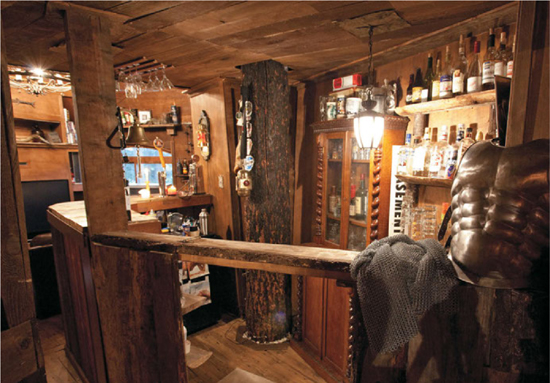

A full bar is a luxury all proper treehouses should afford. This one is put to good use, as I personally discovered during one of the brothers’ renowned Christmas parties. Chain mail and a breastplate from a suit of armor allude to more fun that the brothers engage in at the treehouse.

Avid gamers, the brothers have equipped the treehouse with five TVs—including one on the floor above this and another in the dungeon below—that are all networked so they can play against one another.

The HemLoft

Whistler, BC, Canada

Rookie builder Joel Allen went way out on a limb to build this marvelous masterpiece. With two architect buddies to help with design, and an acute shortage of both tools and materials, Joel crafted a most intricate and organic cocoon. Unfortunately, he built it on land that was not his own, and the cozy cob was doomed for removal. It will live on in many memories, as it took the Internet by storm and inspired many of us to reach for the highest branch and build our wildest dreams.

A thrilling walkway leads to the surreptitious cocoon tucked less than a mile off the nearest road in the backwoods of Whistler.

Looking through a skylight at the trunk of a mighty hemlock.

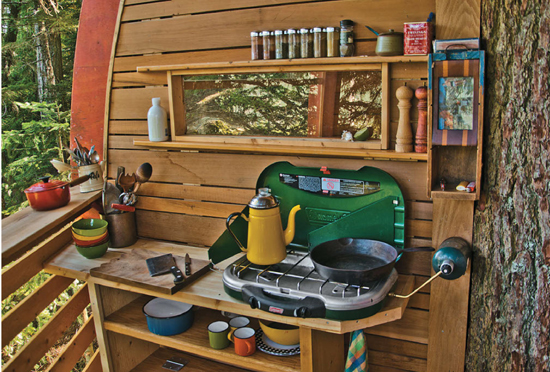

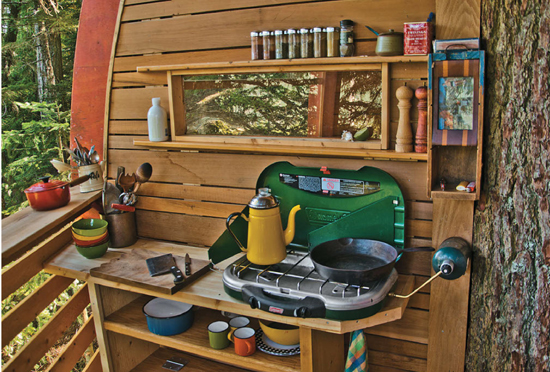

Gourmet camp meals are prepared in the kitchen station.

Lighting makes all the difference. The curves of the walls make this treehouse sublime.

Joel became a Craigslist expert and took full advantage of the deals that are plentiful on the website. He found more than $10,000 worth of free materials!

Accents like the plant stand tell us much about the care and integrity of the man and his building acumen.

Rocky Mountain High

Evergreen, Colorado

Architect Missy Brown outdid herself on this idyllic design after attending a treehouse-building workshop with us in Washington State. Builders Bubba Smith and Daryl McDonald traveled to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains to bring to life her inspired vision. The treehouse serves as a relaxing space for Missy’s brother and his family. To me, this sanctuary embodies all that a meticulously planned and beautifully crafted space can be. The feeling inside is one of tranquility and freedom—unbound from the demands of the earth below.

Flexibility is imperative in every treehouse design. Particularly when you are high off the ground in an exposed area.

This treehouse has seen winds in excess of seventy miles an hour.

Weathered barn boards and corrugated metal are always in fashion with treehouse projects. A bridge or ramp is something I get a request for in almost every job.

Stained pine walls and salvaged fir roof rafters and sheathing lend warmth and authenticity. A small loft provides napping room for one.

The hog-wire railing fits well with the repurposed materials.

A comfortable sitting nook provides an ideal place to unplug and relax.

A wall of books should be required in every treehouse. Here, architect Missy Brown even has a rolling library ladder to reach the highest volumes.

The ladder also gives access to the loft that perches across the narrow space.

Dick and Charlie’s Tea Room

Caddo Lake, near Uncertain, Texas

Lonnie Morrell owns and maintains a one-of-a-kind bayou-style treehouse that has as much history as it has love and dedication to keep it the way it is. On the shore of the mysterious Caddo Lake, a network of bayous spanning Texas and Louisiana, Dick and Charlie’s Tea Room is said to be a relic of the years after Prohibition, when the citizens of Uncertain, Texas, in a dry county, would row across Big Cypress Bayou to patronize wet establishments in stilt houses and “beer boats” in the neighboring county. Lonnie’s dad, J. R. “Dick” Morrell, bought the place for $1,000 in 1975, and Lonnie and his fishing buddies have kept the tea on ever since.

A sign posted outside captures the spirit of the place.

Dick and Charlie’s Tea Room

House Rules:

1. There ain’t any

2. There never was none

3. There ain’t gonna be none

On a smaller sign below, it says:

Waitress wanted

Good fishing boat needed

Cypress trees do 40 percent of the work of keeping Lonnie’s treehouse from falling into the bayou; the rest is done by heavily compromised posts. Other nearby cypress trees, with their odd knees, may need to come to the rescue soon.

The sign that greets you is as much a warning as it is the law of the land.

Lonnie, who strives to keep the original feel of the place, has fastidiously preserved the period kitchen.

The treehouse tearoom hosts a merry band of Lonnie’s oldest buddies, who I had the pleasure of spending the afternoon with at this one-of-a-kind retreat.

A bedroom that appears to be dropping directly into the bayou is still used frequently, if only in the summer.

Attie Jonker’s Treehouses

Lion’s Lair

San Antonio, Texas

Attie Jonker once built safari camps in the Botswana bush country. They started as simple ground-based structures, but evolved into elaborate and often elevated wildlife observatories and retreats. Wise man that he is, Attie followed his American wife back to where she grew up, San Antonio, Texas, and picked up where he left off. He runs a creative building company, Green Wood Milling, and we are all lucky to have him in the States.

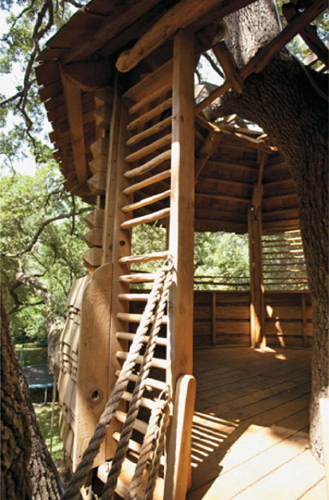

The oak hosting this curvaceous creation spreads 60 feet out in one direction in testament to the tree’s incredible strength. A significant treehouse like this one doesn’t even begin to register as a problem for a tree of this size.

The shingle work on this round pavilion speaks volumes about Attie’s creative aesthetic. Attie sculpts functional art.

Small details like iron rings and salvaged hardware accent his craft.

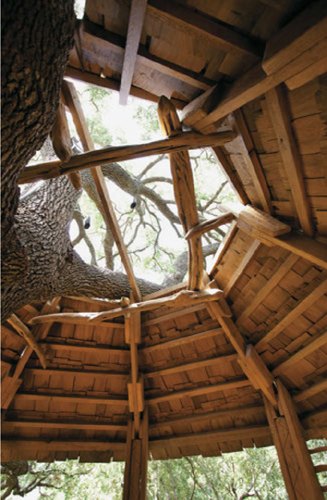

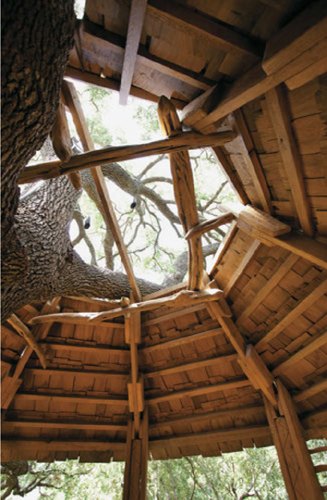

The roof of the pavilion purposely opens to the lofty network of tree branches above. He frames its beauty with peeled mountain cedar rafters

that are art pieces in their own right.

I cannot help wondering if the Texas-sized oak thinks that an enormous bird has nested in its branches.

The Lunch House

San Antonio, Texas

Ten-year-old Alex runs the show at the Lunch House. At least, that’s what he thinks. Attie and I had a fun afternoon taking pictures at this treetop mini barn, and the young master made his apprehension over my appearance known. He simply wanted to use the tree fort, and I was in his way. On such a beautiful summer afternoon, I could hardly blame the little man.

The trapdoor and playful ladder illustrate the level of detail Attie goes to in every project.

A barn door opens to a simple, three-season playhouse complete with a noisy winch used to raise and lower the lunch bucket.

Attie’s ropework is just as refined as his woodwork, and a more enjoyable playhouse there could never be!

The Attic

San Antonio, Texas

Attie fashioned the siding for this Asian-influenced aerie out of the old fence that once surrounded this San Antonio home. It took two people two weeks to cut and apply the shingles, but it sets the place apart.

No two of Attie’s treehouses ever look the same. The steep roof and fish-scale siding make this a particularly playful building.

It serves as a sophisticated family funhouse.

Details like custom screen windows and hand-carved window and door casings accent the equally intricate shingle pattern.

Cabin in the Trees

Ann Arbor, Michigan

Bruce Dondero promised his son Nick a treehouse when they discovered one of my books together nine years ago. After thinking, collecting, and dreaming—and countless hours of glorious work—Nick now believes anything his father tells him. It may have taken a few years, but all good things take time.

The only lumber purchased for the job was the framing for the platform. The cedar for the treehouse came from one of Bruce’s customers (he’s a housepainter) who was re-siding his house. Working together, father and son cleaned it up board by board. The redwood for the door and trim came from an old fence. The roof was inspired by a twenty-year-old article in Mother Earth News.

The bass is Bruce’s. Nick, now fifteen, plays guitars and drums, and his brother plays keyboards.

Bruce admits to an affliction that many a carpenter suffers from—wood hoarding. It is just plain hard to throw good wood away. The redwood for the door and trim showed up last year as an old fence that had been replaced. Put it through the planer and WOW!

Bruce and Nick’s arboreal studio sits 11 feet off the ground on three spruce trees and a few spruce posts for good measure. It is 12 feet square and rises 12 feet to the peak. Everything but the platform is made from salvaged materials.

The siding came from a house that Bruce painted years ago. When the owners chose to re-side their home, Bruce asked if he could salvage the rough-sawn cedar. With a little love and care, he turned it into gold.

A simple open room is finished with materials collected over years. The vaulted roof distinguishes the treehouse as one of a kind. It is made from ten trusses, each built by layering three laminates of ¾-inch plywood. I can imagine the music sounding wonderful in a space like this.

The French Gardener’s House

Annapolis, Maryland

I had the good fortune of meeting master landscaper Pierre Moitrier at a building workshop in Virginia a few years back. After we taught him everything we know about building treehouses, he shared with us some photos of the treehouse that he had just completed in his backyard in Annapolis. It turned out he already knew everything that he needed to know. And I ended up learning more from him—like how to decorate in a sophisticated French style. Mais oui!

A maple in Pierre’s backyard gave the landscape architect the idea to rise above his manicured yard for a better view.

A trapdoor with antique hardware is counterbalanced by a weight, making entry easier when coming up from below.

Fabrics adorn the walls and ceiling of the simple abode, lending softness and warmth to the rustic shelter.

A crystal chandelier highlights the simple decor.

Roderick Romero’s Treehouses

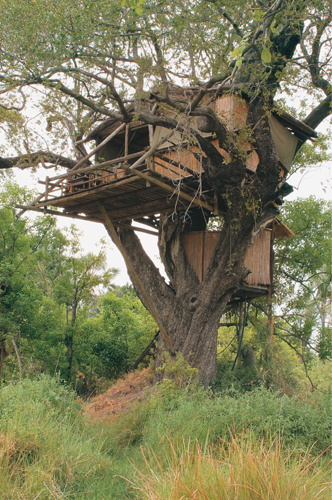

All of these treehouses were designed and built by Roderick Romero. I greatly admire Roderick’s commitment to his vision. The sculptural qualities of his tree structures captivate, the heights are often dizzying (and they are strictly tree-supported), and he always sources interesting and hard-to-find recycled materials. The results are everything treehouses should be.

Dogwood Farm

Connecticut

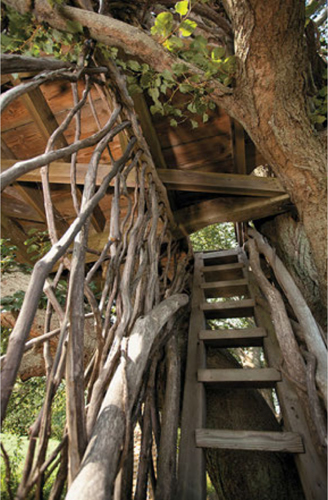

A private client was looking for a sculptural outlook from which to view a vast and undulating property. Roderick is never afraid of placing his creations high in appropriate trees and he is always careful to use interesting recycled materials so that the exposed structure does not look like it came straight out of a local “big box” lumber store.

The chosen materials blend well with three stellar support oaks and the forest behind.

Protecting a stair entrance with additional railing is critical at such high elevations. It is also nice to have a landing somewhere along the way. This gives the designer a chance to change the staircase’s direction and alert the visitor that their outlook is about to change.

The Dogwood Farm treehouse soars 24 feet above the ground and lifts the spirits of all who have the privilege to visit. The beam layout in this three-tree scenario is a little tricky, however. It is imperative that the trees be allowed to move independently of each other, and the distances they move relative to one another can be huge—especially at higher elevations.

Lake Spectacle

Connecticut

Every time I visit one of Roderick’s “babies,” I smile. In this case I nearly cried tears of joy! His signature weaving of branches in bird’s nest intricacy greets you and pulls you in on a journey to a carefree world of lake views and lemonade.

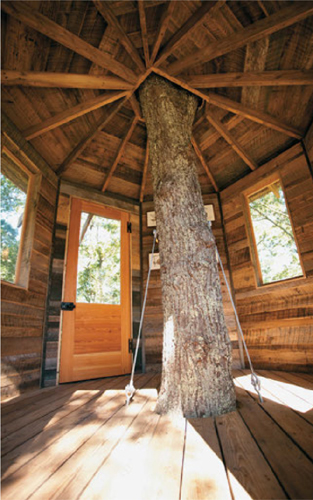

A large white oak anchors the entry stair and bridge that lead 30 feet to a world apart. A lake view awaits at the main platform, along with an octagonal clubhouse that can serve a thousand purposes.

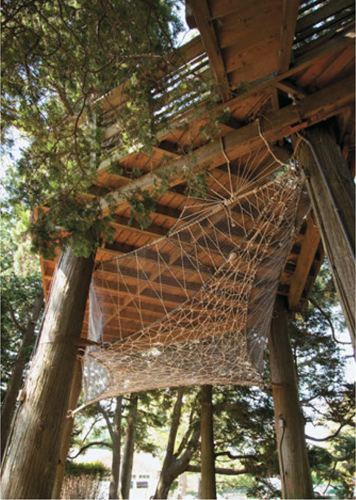

Bridges of this scale pull on the trees with tremendous force. The anchors are short-armed TABs (6-inch boss and 4-inch arm, typically) that are sunk well into the wood of a healthy tree. Heavy chains with a turnbuckle at one end stretch between TABs on both sides of the walkway. Galvanized carriage bolts secure bridge decking through openings in the chain links. Standard manila rope railing is a bad idea. This is a synthetic manila called Hempex that will not shrink or stretch in varying weather conditions.

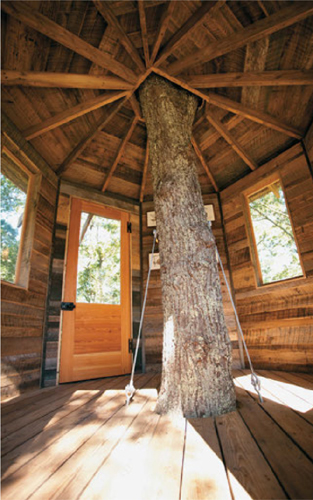

Stairs wind up the trunk without making excessive penetrations into the tree. The stair stringers land on occasional beam-and-brace struts that are visible in the photograph above this one. A sturdy Roman cross–style platform awaits at the top of the stairs and also supports one side of the bridge.

The simple interior of the octagonal aerie is a collection of interesting “mushroom wood” walls, salvaged pine floors,

and an eclectic array of antique doors and windows.

JEM Treehouse

Southampton, New York

The name of this treehouse comes from the initials of the client’s children. Where the design comes from, only Roderick knows. I think it is remarkable. What is also remarkable is the skill of the carpenters who executed the plan and the wonderful materials they employed.

Cedars support an otherworldly Romero creation. Uniform railings front an organic collection of round windows fashioned from heavily textured mushroom wood—a material favored by the designer. It comes from mushroom farms in the Northeast, where it is used for growing platforms. Acid in compost distresses its surface. Growers sell the wood in the recycled lumber market.

Barn doors open wide to welcome visitors from an ample deck into a space like the hull of a cabin cruiser.

Sarah Jefferson, a net builder, came from Washington State to ply her trade of crafting used fishing nets into huge hammocks that stretch between trees.

Small spaces appear larger when they open up to the front. It’s a nice trick that often comes in handy when building in the trees.

Lake Nest Treehouse

Southampton, New York

As it sometimes happens with treehouse projects, forgiveness from building authorities must be asked for after the fact. In this case, Roderick engaged the services of a local architect and a bargain was struck to allow this two-tiered functional sculpture to remain. It would have been a shame to see such a lovely aerie succumb to the nonsense of an inflexible bureaucracy. Instead it stands as an example of how magic can happen when people simply talk with one another to find common ground and, in this case, common air.

The huge tree sprouts through the upper deck and shields the adventurous under its leafy canopy on hot summer days.

A beguiling stairway of branch work and salvaged Southern yellow pine lure upward all who wander close.

When I see something like this, I wonder if humans are meant to be in trees again. Or if, in fact, trees themselves are beckoning to us

to return and reside among their boughs.

Old N.W. Road House

East Hampton, New York

My grandparents lived on Long Island, and my parents had friends we would visit farther out. Every time I return to Long Island’s East End I think of summer, and a treehouse like this is what summer is all about.

Wide eaves help shade the treehouse from the summer sun.

The simplest structures are often the most beautiful.

There is something appealing about having a tree come right through your living room. Just know that there regularly will be maintenance issues with the roof if you need the house to remain waterproof.

Early treehouse design options from Roderick are framed on the back wall. A translucent art piece forms a window in the center.

James “B’fer” Roth’s Treehouses

Michael’s Memorial

Warren, Vermont

James “B’fer” Roth builds beautiful, heartfelt treehouses and rustic furniture in Vermont’s heartland. Formerly the lead designer and builder of a company that specialized in wheelchair-accessible treehouses, he now runs a company called, simply, The Treehouse Guys.

One afternoon, B’fer received a call from an acquaintance asking if he might help create a long-dreamed-about treehouse in the man’s backyard. The kicker was that the man, Michael, had been recently diagnosed with pancreatic cancer and had only a few short months to live.

The result is a structure built with playful integrity and pure love.

A dead hemlock in Michael’s backyard was the impetus for renewal and rebirth. In the old tree’s place, a new point of interest, an inspiration, stands as a memorial to an artistic soul who left this earth far too soon.

Playful use of recycled doors, windows, and bicycle wheels give insight into who the wonderful man, Michael, was.

Locust log posts do the work that the once-proud hemlock can no longer do. Branch-and-wire bracing will ensure stability for many years to come. It is said that locust posts can be planted directly in the ground and last for fifty years.

Zeno Mountain Farm

Lincoln, Vermont

I was fortunate to build with B’fer a few years back in Pennsylvania, and I am pleased to see his beautiful work continue. Here, his craft goes on at Zeno Mountain Farm in Lincoln, Vermont. The farm is an organization that runs camps for people with and without disabilities. They have a great website, so please check it out at www.zenomountainfarm.org!

Two treehouse cabins sleep the campers. This one, called A Long Way Up, hangs from beech and maple trees and locust log posts. The main cabin sleeps twelve and the structure on the right houses the bath facilities.

Grandpa’s Treehouse, named for its sponsor, sleeps eighteen campers and on nicer days looks out over a vast Vermont vista. Plumbing a treehouse is a question people often ask about. The white plastic pipe in this photograph indicates that plumbing for waste is not much different from plumbing a regular house—but here you have a much larger “crawlspace” to work in!

Quirky windows define B’fer’s treehouse designs, as do the rustic materials that he sources from local mom-and-pop sawmills.

Only experienced campers are allowed the top bunks in this network of nighttime nests. West-facing windows let the summertime sleepers get as much shut-eye as the camp counselors allow.

The forest appears to come inside where a rookery of sleeping nests fills the canopy.

Topridge

Upstate New York

A few years ago, our company had a treehouse story appear in Architectural Digest. It caught the eye of a whimsical property owner in New York and was passed to the property manager and then into the hands of a carpenter named Jim. That was the beginning of what turned into a most extraordinary and ambitious arboreal undertaking. Good planning and attention to detail assured success, and I am proud to add that Jim, charged with building the one-off perch, attended one of our building workshops in Washington State. Little did we know at the time what Jim was capable of.

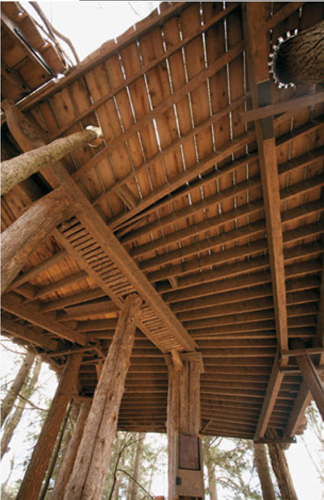

Used as a guesthouse, it sleeps four adults comfortably and boasts a full bathroom with hot and cold running water. Outside, a meandering stairway threads up through mature hemlocks to a height that can exceed 25 feet above the forest floor. Outdoor decks and walkways surround the entire structure and provide outlooks to the forest and adjacent lake.

The lofty retreat was carefully engineered. An effort of this magnitude absolutely requires the attention and blessing of a professional structural engineer. For this project Charley Greenwood of Greenwood Engineering in Oregon stepped up in brilliant fashion. I can imagine he was a source of consternation for Jim and the building team, as complex building jobs will often outstretch the patience of many a carpenter, but the design was followed faithfully, and despite a midwinter build in the wild North Country, Jim orchestrated a flawless execution of the plan.

After seven seasons aloft, the building is wearing well. At such heights, the worry is that the trees will move radically in high winds and damage themselves, the structure, or both. In fact, after the 2011 hurricane that wreaked havoc throughout New England and upstate New York, the treehouse came through with flying colors—a tribute to all involved: the owner, the engineer, the builders, and especially the trees themselves.

The Adirondack camp building style is alive and well in its native land. Here the bark-on-branch work leads to a heavenly treetop haven.

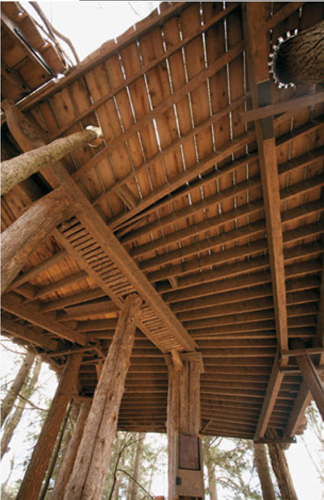

The substructure is nearly as beautiful to observe as the structure above. The center post is a hollowed-out log that houses all of the treehouses’ utility lines.

Carpenter Jim, the man behind the saw on this wondrous masterpiece, participated in one of our treehouse-building workshops in 2006. Little did we know at the time what he was capable of, though I had my suspicions.

The treehouse serves as sleeping quarters for a lucky few who visit the summer camp. This is the master suite that greets you directly from the entry door.

The entry door is a work of art in itself. Walnut panels below the inlaid tree branches open to screens that allow cross ventilation, but not bugs and buzzing insects.

A satellite bedroom sleeps two more.

A burl sink took countless hours to finish and sets the tone for the lavish full bathroom.

Drynachan Lodge Treehouse

Cawdor, Scotland

WSJ., the Wall Street Journal’s magazine, was laying out at my sister-in-law’s house when she remembered to show me an article about a young family that was transforming their ancient Scottish family estate into a partridge-shooting lodge. And they had a treehouse. Only weeks later Judy and I found ourselves hurtling through the desolate Scottish moor in a rental car, searching out the Drynachan Valley and the current thane of Cawdor and builder of said structure.

Lord Cawdor, or Colin, as he prefers to be called, moved his new wife, Isabella, to this 80-square-mile family estate in 1994 with the intention of sprucing up land that had been in the family for 800 years and being closer to the place where he would raise a family. Trained as an architect at the Pratt Institute in New York City, he instead wandered into finance and found himself commuting between London and “the farm” on weekends. Meanwhile, his four children were growing up in an idyllic setting. As a way of connecting with them, he built his masterwork in ancient alders on the banks of the River Findhorn between 2003 and 2005. It was built for the kids, but it was really a therapy project for Colin to get away from thoughts of work back in London.

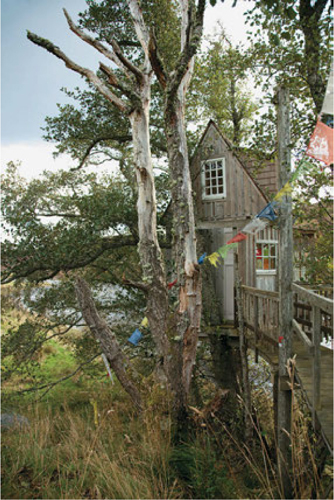

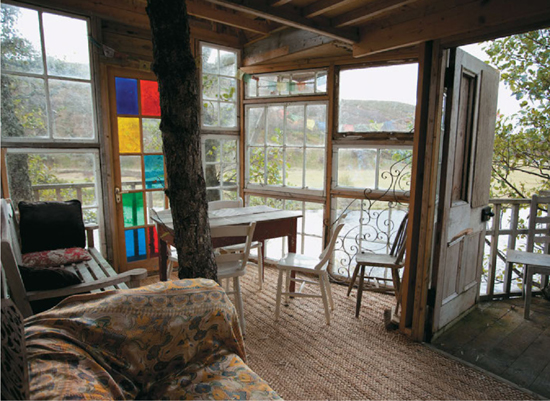

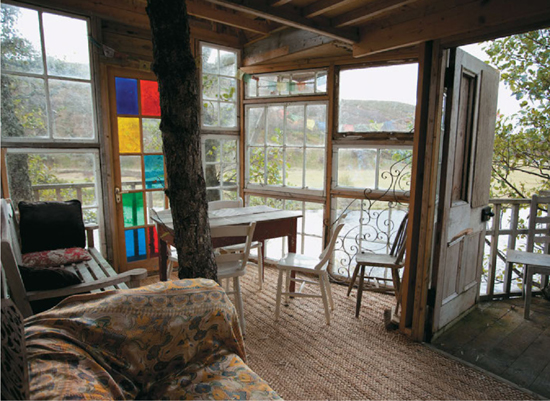

Year one produced a platform squarely nailed to the trunks of the alders with two-by-sixes, and little room for growth or movement. Year two yielded the house itself, cobbled from old doors and windows that he found stashed in buildings around the estate. The steep roof and requisite dormer proved more than he could build himself, so he hired a local roofer for that.

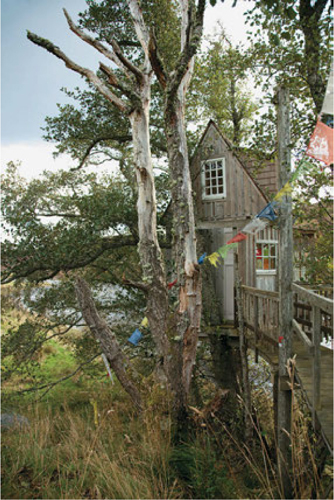

Lord Cawdor, a trained architect, assembled doors and windows that were stashed in outbuildings on his Scottish family estate. He turned them into this riverside retreat high on the trunks of several old and weathered alder trees.

A glimpse between the trees from the riverbank below reveals a different view of the newest building on the 80-square-mile family estate.

Prayer flags shudder in the wind and welcome visitors to a peaceful sanctuary on the River Findhorn.

Salvaged windows, thoughtfully arranged, make up the entire west end of the small space.

At first the kids were intimidated by all the glass, but now his sixteen-year-old is spending more time in the treehouse—especially when she has friends visiting.

Treehouse building, in a sense, goes a very long way back in the Cawdor family. The original castle, where Colin’s stepmother still lives, was built around an enormous holly tree—quite literally. The tree was encased in the grand stair foyer where, without all of the tree’s needs met, it died, but it remains to this day. Colin’s father had the tree carbon-dated to get a better idea of when the castle was actually built. The results showed somewhere around 1340 or 1350. While his ancestors built a tree into a house, Colin built a house in a tree.

There is room above for Colin and Isabella’s four children to share sleepover rights.

A seagrass rug and an eclectic collection of simple furnishings are all that adorn a cheery, light-filled room.

A farm table awaits the next heated board game or family picnic. Outside, the River Findhorn quietly rolls by.

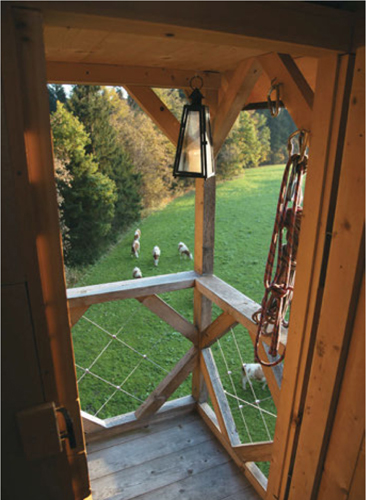

Tyrolean Treetop

Mariastein, Austria

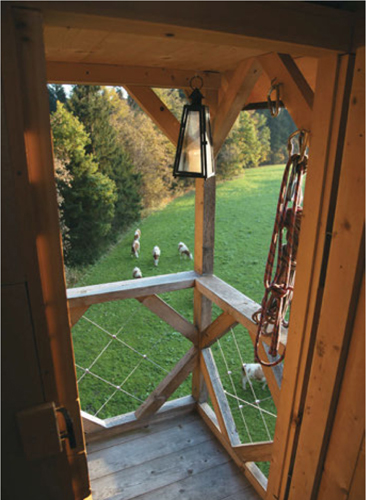

Bernd Weinmayer is a glass artist of the highest order. His creations are on display in a glassblowing studio that he built twenty years ago on his family’s property at the foot of the awe-inspiring Austrian Alps.

It turns out that Bernd is a crafty woodworker as well.

A few years ago he sent some photos of a treehouse that he decided to build on the edge of a forest directly behind his shop. Perched atop a living tree that had lost its crown in a storm, it was a place to climb up to, unplug, and recharge his creative soul.

When I contacted him, I was distressed to hear that a beetle infestation had killed his tree.

Rather than abandon ship, Bernd chose to rescue the abode by cutting it down. He called a crane buddy to balance and keep everything upright, and proceeded to relocate the entire structure to an outside corner of his studio.

Having now witnessed firsthand Bernd’s building acumen, it was no surprise to see the beefiness of the concrete retaining walls that held the earth back from his semisubterranean glass studio. Relocating the treehouse simply involved designing and fabricating a footing that he could bolt to the concrete walls to support his previously ill-fated aerie.

He did a wonderful job.

The Tyrolean Alps rise high in the background of this towering hermitage. This is the retreat of a famous glassblower,

whose studio is built into a hillside just below.

Wood-boring beetles attacked the tree in its former location, so Bernd decided to cut and move the fracas, treehouse and all,

to a sturdy location steps outside of his office.

Bernd fits a lot into a tight space, as all good treehouses should. Be careful with woodstoves, however.

They can generate more heat than a small space can comfortably handle.

Tyrolean cowbells alert us to the arrival of visitors below.

Art Farm

Kalamata, Greece

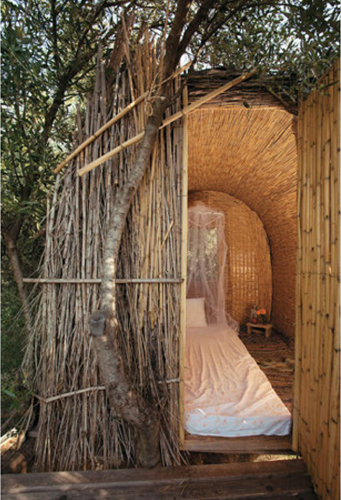

Sotiris Marinis is a man of indeterminate age. He looks like he could be in his forties, but his bright, burning eyes, wild gray hair, and knowing smile reveal the wisdom of a man much older. Olive trees and the oils they yield play a role in keeping him young, and now olive tree huts, or eleokalyves, are taking center stage in his play with age.

This is not the first time that treehouses have played a role in Sotiris’s life. At eleven years old, he became famous in his village for building a treehouse with lights. Each summer he would build a small hut in the moria trees near the beach. There was no electricity in his town, and at an expo in Athens he learned to use a simple battery, switch, wire, and a lightbulb. People were amazed. These were the first lights in the area. His mother said, “My brilliant son! You should become an electrician!” Which he did.

Sotiris had a long career as an electrical engineer. Now he is the owner of a five-acre “art camp” that houses guests in rustic olive tree huts that overlook the turquoise Aegean Sea.

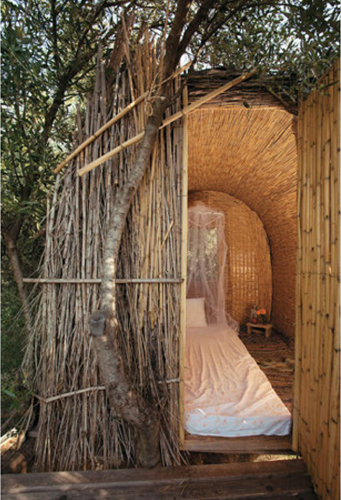

His style of building treehouses is all his own.

Wood platforms, some fashioned from large wooden wire wheels, balance low in the olive’s branches—sometimes posted to the ground with 2-inch round steel columns. From there he creates a light steel rebar framework that he welds together himself. The frame serves as the house’s shell and a surface on which to attach the different layers of construction—first a layer of light bamboo to lend the interior warmth, then a layer of plastic to keep out the elements. Finally, he goes down to the river and harvests reeds to finish the outside and weave the doors and windows. It is simple, and in the climate of southern Greece, it works.

The Art Farm is a dream in the making. A 750-person amphitheater is nearing completion, and a building to house an artisan blacksmith, cheese maker, and, of course, olive oil producer is awaiting funding. Judging by the progress he has made in four short years, there is no doubt that the art camp hotel will be a beautiful success.

Olive trees were not high on my list of suitable treehouse trees until I visited Sotiris Marinis’s farm in the famous Kalamata olive region of Greece.

Sotiris used a large wooden wire spool for the floor of his simple tree hut. He harvested reeds from a local river for use as siding and roofing.

I had the company of two white cats that followed me from hut to hut as I took my pictures. Despite not advertising, the cats are not the only visitors to the Art Farm. Backpackers routinely hear of the place through the grapevine and arrive unannounced.

Tea is set for two in the smallest of the tree huts. The floor area is only seven feet in diameter.

The largest of the four tree huts is supported by two posts and an olive tree. It is only 5 feet wide and 10 feet long.

There is something highly romantic about sleeping in a tree. Doing so in Greece only adds to the appeal.

Bathroom facilities and a communal kitchen are only a few steps away from all of the elevated reed houses.

They serve simply as places to sleep, relax, and seek shelter from the hot sun.

Dylan’s Africa

In November of 2012, Dylan Rauch, a key member of my carpentry team and new photographer, set out on a journey to Zimbabwe to visit his mother, a Fulbright scholar, in the capital city of Harare. With so much happening on the treehouse front at home, we determined that this would be the perfect opportunity to see what kinds of tree structures sub-Saharan Africa had to offer. Dylan extended his trip by a few weeks for an epic adventure in treehouse scouting, traveling everywhere from the deltas of Botswana to a remote island off the coast of Kenya. His steady demeanor and adventurous spirit made him the perfect man for the job and led him to discover some truly incredible treehouses. It was a tough job, but someone had to do it.

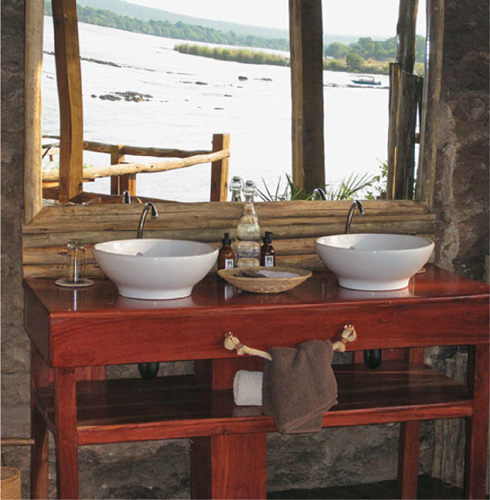

Tongabezi Lodge Treehouse

Livingstone, Zambia

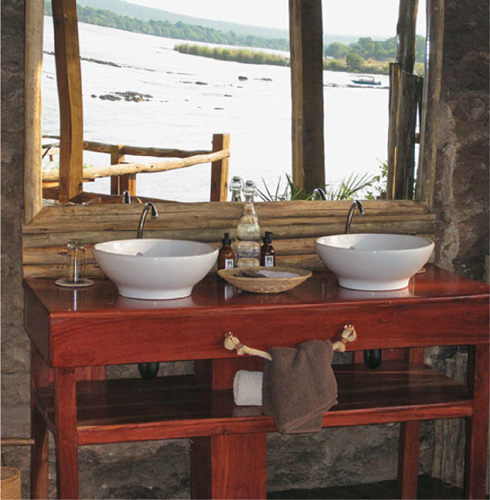

After spending a couple of weeks exploring Zimbabwe with his mother, Carol, and teaching carpentry at Chiedza Child Care Center, Dylan set off on his treehouse adventure. First stop: Livingstone, Zambia. After a roundabout airplane journey via Johannesburg, South Africa, Dylan landed in Zambia, where he was greeted by a man named Faden, who drove him to the Tongabezi Lodge, a lavish resort built along the bank of the Zambezi River. Dylan found himself in the setting of a truly luxurious, romantic getaway in a wild place—complete with vervet monkeys swinging around and the snorts of hippos in the not-so-far distance. The grounds run along the contour of the riverbank, and a narrow walkway that winds along leads guests to the private love nest that rests in the boughs of the trees. The open-air treehouse is perched right over the river and nestled up against a textured cliff face that makes up the only full wall in the structure. The treehouse is fully equipped with a claw-foot tub and toilet, and it overlooks the river that marks the border between Zambia and Zimbabwe. A luxurious king-size bed and sitting area make this treehouse top-notch—according to our lucky traveler.

This open-air guesthouse sits on the bank of the Zambezi river. Guests can soak up the beauty of their surroundings while they relax on a pine deck.

This exotic treehouse is fully equipped with a private shower and a claw-foot tub.

The bathroom mirror reflects the stunning view.

The structure’s rear wall is basalt rock, and trunks of a riverine ebony tree rise through the floor.

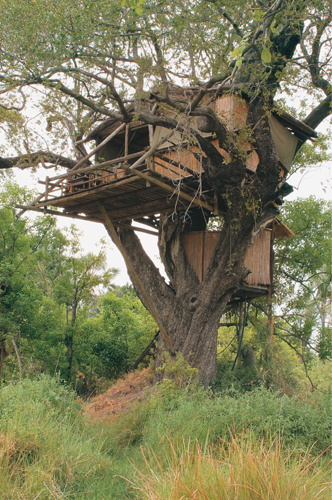

Delta Camp Treehouse

Botswana

After being pampered in Zambia, Dylan flew on to Maun, Botswana, by way of Johannesburg. It was there that he was met by a private plane piloted by a woman named Tepo-Tepo (which translates to “trust”), who flew him over the vast Okavango Delta, the largest inland delta in the world, and safely landed their Cessna on a small dirt runway amid the lush waterways. Three luxury safari camps are tucked neatly into the delta, which is navigated by canoe. The water level happened to be low when Dylan visited, and when night fell, the glow of wildfires burning in the distance created a spectacular sight. After a minor detour due to an elephant crossing, Dylan was led to Delta Camp Treehouse by his three hosts, Poison (so dubbed for his deadly skills on the soccer field), Matt, and Ponay, the manager. The treehouse is built in two jackalberry trees, the Latin name of which is Diospyros mespiliformis, a fact that Poison, the resident naturalist, recited from memory. The structure has two stories connected by a staircase that leads first to the facilities—complete with a toilet, sink, and shower. Continuing up the staircase, you arrive at the second story, which includes a charming bedroom and a cocktail deck that is perched over a lagoon. The billowy white mosquito net curtains give the treehouse an airy and romantic feel—making this another love nest suspended within the African wilderness.

Sitting in an old-growth jackalberry tree, this treehouse is built from local materials.

The lower level is a bathroom that has hot and cold solar-powered running water.

The elevated lodge looks out over the surrounding bush and floodplains that host an incredible array of wildlife, including giraffes, leopards, and elephants.

A small set of steps leads down to the cocktail deck from the sleeping area.

Salvaged wood makes up the floorboards, and hand-carved shelving demonstrates the skills of the local craftsmen.

A cocktail deck overlooks a favorite watering hole for local wildlife.

A queen-size bed is perched on the upper floor of this classic treehouse. Equipped with mosquito netting, the bed has 360-degree views of the savanna.

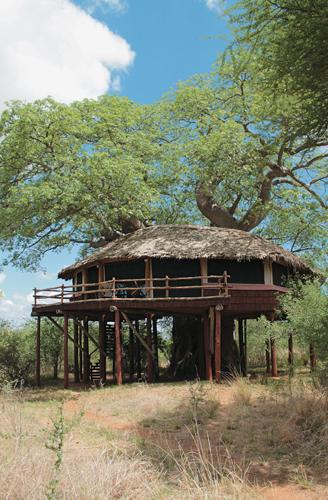

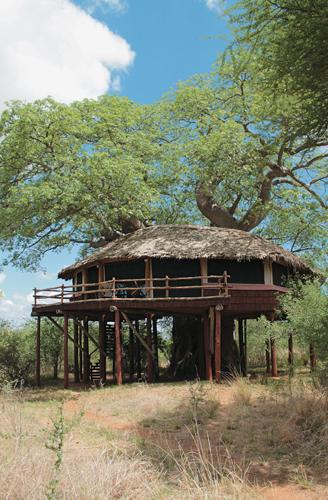

Tarangire Treetops

Tanzania

On the third leg of his journey, Dylan found himself flying above Kilimanjaro and into an airport outside of Arucha, Tanzania. After a three-hour car ride through the arid desert of Kenya and into the rocky terrain of northeast Tanzania, Dylan arrived at the Tarangire Treetops resort. Massive baobab trees measuring about 12–16 feet in diameter greeted Dylan as he explored another deluxe establishment. Baobab trees have an incredible water-retention system in which water is stored in the hollow middle of these broad trees. Treehouses are not the only abodes situated within the baobab trees; bats often make their homes in rotted-out cavities of these gentle giants. The property has twenty luxurious elevated houses making up the safari resort. The screened-in houses allow guests to enjoy the fresh air and wildlife from the comfort of the treetops.

Here is one of the twenty elevated tree rooms at Tarangire Treetops. The screened-in porch creates an open-air feel and

presents an expansive view of the Tarangire plains.

Locally made furnishings, an exposed baobab branch, and a king-size bed fill the luxurious guest room.

This baobab tree is estimated to be one thousand years old and has a hollow center filled with water, allowing it to survive during severe droughts.

One Love Island Treehouse

Ngomeni, Kenya

After hearing about a small treehouse on remote One Love Island off the coast of Kenya, Dylan embarked on the last leg of his journey. A plane ride, a matato (minibus), a “drive-yourself taxi,” and a kind man named Madi led him to a little village called Ngomeni. It was there that Dylan was met by Captain Ali, who silently canoed him, guided by the light of the full moon, across the turquoise Ungwana Bay to the island. White sand and tropical palm trees surround the island, which serves as a hostel and public lounge space for the people of nearby villages. The charming treehouse is built using wood from mangrove trees and reeds from the local area. Despite there being no amenities on the island, Dylan was fed delicious lobster dinners and slept in an open-air pavilion during the intensely hot and humid afternoon.

I can’t promise that everyone who comes to work for Nelson Treehouse and Supply will have these kinds of experiences and opportunities, but it will always be something that we keep our eyes and ears open for! Well done, Dylan. And thank you.

A view of the Indian Ocean. The picturesque One Love Island is used as a hostel and public park for the people of Ngomeni.

The charming structure is used for overnight accommodations and as an escape from the sweltering sun.