The Extrasensory Mind Mound

Our setting for a new approach to ESP will look barren if it has a single backdrop made only of the potential for people to experience ESP.

There is nothing on this backdrop yet, but so far we can understand why the stage should be emptied of scenery and props left over from past productions that attempted to enact ESP. Those productions closed down after limited runs.

To begin to construct the scenery necessary, let’s start with an assumption that may be true: that extrasensory perception and the mind are probably inseparable. Without a mind (or brain) upon which to register its astonishing and transrational activities, who could ever say whether or not ESP existed in the first place? We can refine this a little, and say that extrasensory perception registers its information in those awarenesses that are prepared to receive it, or are not blocked from doing so.

Thus, the territories of our minds should make up the basic scenery of our new ESP. We have to describe this, but in terms that can be self-experienced and not in labels that prohibit experience. Psychology has evolved a lot of labels for various aspects of the mind, only some of which are useful for our purposes.

If we were to use these labels for our ESP stage, it would look strange indeed, and quite unaesthetic. Over here would be a label for ego, and over there would be a label for unconscious, and somewhere else would be the label for superconscious, and perhaps additional labels for consciousnesses 1, 2, and 3. We might slip in labels for soul, dreams, spontaneous experience, reverie, altered states 1 through 20.

We could read these labels, but nothing in them would help us experience what they mean. What we need in order to evoke the self-experience of our minds are constructs that we can intuitively identify with, that have a ring of truth in them. We cannot simply say, “Self-experience your mind.” It doesn’t work that way, even though we are experiencing it every moment of our lives. We need to cause parts of the mind to resonate with objective words, to reveal themselves as real, and for that realness to be intimately familiar to us all.

About the only way to do this is through the use of analogies. There are many we could use, but I ran across one that seems particularly suitable. It has three advantages: It does not utilize labels, it is not disprovable by psychology, and it evokes experiential response.

It was written in 1904 by the psychologist Denton J. Snider, in a book with the long title, Feeling Psychologically Treated and Prolegomena to Psychology. Snider’s book is a wonderful excursion into the phenomenology of the mind as it more or less existed before Freudianism (which gave us so many labels) came into domination and before the rise of specialized mechanistic psychologies (which gave us many more). Snider wrote:

Taken in its literal simplicity, Psychology signifies the science of the Soul, or of the Mind. Even such a definition gives to it a broad sweep which has been narrowed in various ways by different writers, who have in them the prevalent bent toward specialization. At the present time, the most common view of Psychology holds it to be the science of the phenomena of the mind, such as perception, sensation, memory, which this science finds and picks up (so to speak), and then proceeds to describe and to put into some kind of order. As there are phenomena of Nature with which physical science deals, so there are phenomena of Mind with which psychological science deals. As there are classes of flowers, so there are classes of mental activities; as there are strata of the earth in geology, so there are strata of the mind. Next we may note the difference between the two kinds of phenomena. The geologist perceives the stratum and arranges it according to his scheme; but if he perceives himself perceiving the stratum, he no longer geologizes but psychologizes. The moment his mind passes from regarding the outer object to regarding its own activity he changes to a new field which has its distinct science. A wholly different set of phenomena rises to view.

Snider’s “distinct science” is, of course, built upon distinct experience. I think we can all agree, if we try to observe the workings of our own minds, that in them we can experience classes or even species of mental activities. Beyond the classes of awake mental activities, we can also experience deeper strata or levels in our minds. We already know which of these strata are frilly and which are profound. We are aware of sinking through strata when we meditate or fall asleep, and rising through levels when we approach wakefulness.

We can add to Snider’s two qualities another called boundaries, and say that like things in nature that have different boundaries, the mind can experience different boundaries. When we drink too much, have a peak experience, take a psychoactive drug, or experience a wonderful symphony or rock group, we can experience our mind’s boundaries changing.

We don’t necessarily need labels for these mentally experienced phenomena. They go on all the time inside our minds with or without names for them.

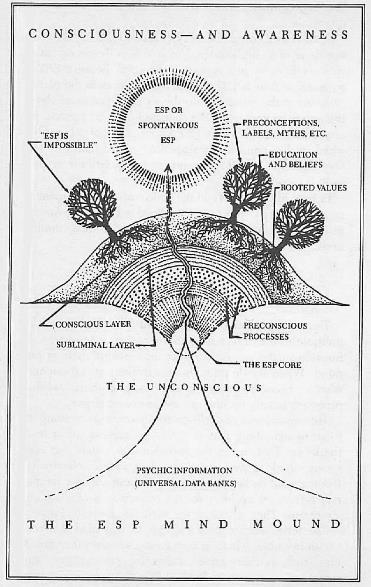

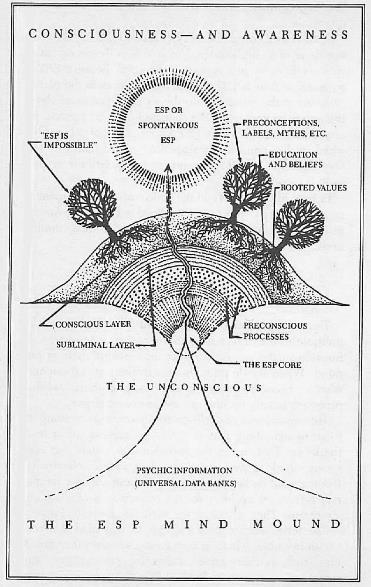

It is these different classes of mental activities, the different mental strata, and the different changing mental boundaries that will make up the scenery on our new stage. Extrasensory perceptions work and function among all these, and it is among these that we can experience firsthand the elements of extrasensory perception and its many different qualities. Somewhere in each of us is a particular classification of all these that I would like to call the “extrasensory mind mound.” This term is dangerously close to being yet another label, but not exactly so. It is an allegorical label which tells an experiential story, rather than an intellectual label which is empty of experience.

The extrasensory mind mound is like one of those huge mounds found in the deserts of Turkey, the plains of the American Midwest, or the jungles of Mexico. Outwardly, the mound has trees and shrubs on it, and it rises a hundred or so feet into the air, resembling a hill. Sometimes these mounds served as dumping grounds, and small relics are found—a pottery cup, an arrowhead, a small carved idol.

When archaeologists begin digging into the hill, it is not a hill at all, but the remains of a fortress city, a majestic burial ground, or a large temple. Slicing into the mound, the archaeologist finds the foundations, the rooms, the arts, the ancient inscriptions. From these clues, the archaeologist can recreate the life-styles of the former inhabitants, and begin to intuit their motives and goals which had for centuries remained invisible, unknown, and intangible.

With regard to extrasensory perception, though we do not think of a shrub-covered mound in a desert or plain, we have to envision a mound in the mind, because ESP is a mental craft or art. This mind mound lurks in the planes or levels of the mind. Its shrubbery is that of ideas about the nature of ESP that have collected upon its surface. Its artifacts are spontaneous ESP experiences or lab results which really cannot be explained any more than the pottery shards and small idols—not, at least, until the mound itself is penetrated.

In spite of the artifacts on the surface of this mind mound, no one has dug a trench into it, sliced into its core. And so its internal secrets remain covered by its outside accumulations.

ESP Processes Are Invisible

The psychic processes in the mind mound are normally invisible to our direct mental perception. They probably function in the preconscious or unconscious parts of our mind. When we do undergo an extrasensory experience, what we become aware of are the results of those invisible processes poking up into our awake consciousness.

The normal way of dealing with invisibles is to compare them to something that is visible or tangible, or at least thinkable. That brings the invisible into a state our conscious, thinking awareness can deal with intellectually. But it should be borne in mind that these are only-temporary references made up for the convenience of conscious awareness. They still cloak the invisibles beneath them.

The term “extrasensory perception” is a label that covers an invisible, which in turn covers several other invisibles, such as clairvoyance, telepathy, precognition, and remote viewing. An individual “sees” an activity taking place a thousand miles away, and when this is confirmed, people say, “Ah, that was clairvoyance.” This is good only so far as it goes, but it doesn’t tell us anything at all about what happened during the process labeled “clairvoyance.”

From the beginning of organized inquiry into human psychic phenomena, extrasensory perception was expected to mimic the physical senses; that is, through ESP we would “see” as our eyes see, “hear” as our ears hear, and “feel” as our tactile senses feel. There was some justification for this expectation because in examples of high-stage ESP, this was indeed the case. The percipient (the one having the ESP experience) sometimes had ESP impressions so clear and precise that it seemed he was seeing with his eyes.

When this is the case, it is easy enough to understand the mistake in thinking that ESP processes always work that way. In reality all we have is the result of the invisible processes spontaneously functioning in their high-stage condition. This high-stage functioning serves to confirm our expectations and reinforces our thinking that the result is ESP itself. All this leads us away from any contact with the invisible processes that produced this kind of result. As we shall see, ESP is actually several different kinds of processes, a series of “mind manifestations” that invisibly take place when an individual is endeavoring to use ESP in some form.

While we will delve into specific aspects of the invisible ESP processes, we don’t want to lose track of the greater implications. Specifically, we don’t want to make the mistake that has so often been made—we don’t want to detach the ESP result from the greater invisible psychic system and put it by itself under the magnifying glass to the detriment of losing touch with the greater psychic realities that produced the result in the first place.