BY THE EARLY SUMMER of 1985 the twenty-year-old Keanu Reeves was ready to capitalise on his local Toronto triumphs – his stage work in Wolfboy and appearances in TV bit parts, as well as his feature film debut in Youngblood. He was ready to leave home and move to Los Angeles to pursue a serious Hollywood film career. Winning the part in Young Again was the ideal reason for finally leaving home to pursue his career.

It was a pivotal time in his life. Although his trip to Pennsylvania had taken him away from home, the longest Keanu had been living away from his family had been several weeks camped out in a friend’s basement while his mother renovated the house. It was clear to him, though, that he could do little more in Toronto to further his career. Parts would, of course, be much more available in Los Angeles than they had been back in Canada, when Keanu had to wait for visiting projects filming on location, or rare local productions, before he even got a shot at an audition. It was time to put the schooling and classes behind him and move his professional life on.

‘I was at a point where I had done the most I could do in Toronto. I was tired of playing the best friend, thug number one and the tall guy,’ said Keanu. ‘I got into my dumpy 1969 Volvo and drove here with $3,000. I stayed at my stepfather’s and proceeded to go into the darkness that is LA.’

It was natural that, upon arriving in LA looking for work, it was to Paul Aaron the young actor would turn. It also meant he could let Aaron know about his mother Patricia’s latest marriage, to fourth husband – hairdresser Jack Bond. Aaron’s advice to his stepson had been carefully parcelled out through the years. He didn’t want to be seen to be pushing the young man into an acting career, but neither did he wish to stifle Keanu’s developing ambitions. Offering house room to Keanu was one way of ensuring that he had a decent start upon arrival in LA. Aaron was to play a more decisive and long-running role in Keanu’s professional life, by suggesting that the would-be actor see Erwin Stoff, who in the mid-’80s was just setting himself up as a Hollywood talent manager.

Stoff was to develop over the years from 1986 into an old-fashioned talent manager, one who devotes his attentions to a handful of specific clients. His 3 Arts Entertainment company was in the forefront of a late ’80s resurgence in management companies.

‘Agents look at themselves as covering the marketplace,’ warned the bearded, balding Stoff. ‘We look at ourselves as covering the client.’ Whereas agents at big agencies tend to handle around 60 clients each, at 3 Arts each rep focused on about fifteen key people and became more involved in career management than individual film deals. Separate agents would handle those deals.

Keanu was convinced and signed on with Stoff, who worked quickly and found him a traditional Hollywood agent in the shape of Hildy Gottlieb Hill, then head of talent at the International Creative Management (ICM) Agency. ‘In twenty minutes I was crazy about him. He was very fresh,’ recalled Hill of her first meeting with Keanu Reeves. After the actor had left, Hill boasted to a colleague: ‘I’ve just signed a new client, and I don’t even know if he can act . . .’ It was to be a question audiences and critics would be asking about Keanu Reeves throughout most of his career – can he really act?

Such concerns were not at the forefront of Keanu’s mind. He just moved out of Paul Aaron’s rented home into an apartment of his own on the corner of Fairfax and Beverly. He was where he wanted to be – in Hollywood, signed with a manager and an agent – and he had the title role in the Disney TV movie Young Again.

The story had 40-year-old Robert Urich wishing to be young again – and magically turning into Keanu Reeves. As the young Urich, Keanu goes skateboarding, disco dancing and visiting malls. Returning to school, though, the older Urich in the younger Keanu body felt terribly out of place. The role won Keanu a rave review from Variety after its May 1986 TV screening. ‘Reeves steps in with terrific success as Urich the youth. . . Reeves’s open-faced, exuberant study of the boy who turns into a young man in love goes a long way towards keeping the fantasy in the realm of reality.’

Now all he needed was a stand-out role, one that would make Hollywood sit up and take notice of the new arrival. It wasn’t to happen immediately, but before the year was out, Keanu Reeves would have made the film that marked him out as a talent to be watched closely. He was a picky newcomer, too, apparently turning down the lead role in Platoon as because he objected to the violence and guns, according to director Oliver Stone. ‘He was a bit of a pacifist at the time,’ claimed Stone, ‘. . .had a real thing about guns.’

It was an opportunity missed, but a sign of some of the eccentricities to come in Keanu’s selection of roles. Platoon went on to win four Oscars, including one for Best Picture. The lead part was played by Charlie Sheen, who was nominated for Best Actor. Although Sheen pipped Keanu to the role at this early stage in the actor’s career, he was later to be envious of Keanu’s more consistent successes, as he told Movieline magazine. ‘Emilio [Estevez, Sheen’s actor brother] and I sit around scratching our fucking heads, thinking, “How did this guy get in?” I mean – how does Keanu work with Coppola and Bertolucci and I don’t get a shot at that?’

Keanu was to look back on his beginnings in Hollywood, and consider how his approach to his career had changed: ‘I jumped into acting without an ultimate goal, and it’s just recently that I’ve realised that I don’t have any goals. In the immediacy of being in Hollywood, now in my life as it is, I would like to play a very neurotic, crazy, preferably mean, evil character. Most of the characters I’ve played so far have been good people; they all, in a sense, are in possession of sort of a naiveté. I guess that’s me, and I’d like to explore and exploit some other stuff.’

Keanu was spot-on in analysing his own typecasting. Although he was twenty when he arrived in Los Angeles, his baby-faced good looks resulted in years of casting as teen high-schoolers with problems – a role he was overly familiar with from his own real life experiences in Canadian high schools.

Earning his Screen Actors Guild union card became a first priority for Keanu, and winning a role in the 1986 TV movie Under the Influence was his ticket to union membership, even if that particular film had its drawbacks, such as reporting to the set at 8 a.m. every morning. ‘I thought this was . . . unfair,’ admitted Keanu. ‘It’s hard to act in the morning. The muse isn’t even awake . . .’

Starring in the above-average TV movie was Andy Griffith as family man Noah Talbot, who refuses to acknowledge he’s an alcoholic. Keanu featured alongside Joyce Van Patten, William Schallert and Season Hubley, under the early morning direction of Thomas Carter. The movie had been written by recovering alcoholic Joyce Reberta-Burditt, drawing on her own experiences to produce an incisive script that delivered a powerful message.

Keanu was cast in the role of Eddie, the second son in the family after Stephen (stand-up comedian Paul Provenza), who has turned his family experiences into routines he performs on stage. Keanu’s character of Eddie does not have that escape option and so hopes to both impress his father and rebel against him by becoming like him, by drinking and risking the dangers of alcoholism himself.

Of Keanu’s very early performances prior to River’s Edge, Under the Influence was the most accomplished. Although part of a large ensemble cast, Keanu more than held his own against the TV veteran Andy Griffith. More importantly, in the loathing of his fictional father, Keanu seemed to bring out something of his own hatred for Samuel, the father who had abandoned him. And as his character drifted to becoming an alcoholic like his fictional father in Under the Influence, Keanu found echoes of his own fear that he would turn out to be an addictive personality like his drug-addicted real-life father and abandon his relationships. It was to be a fear which would prevent the actor from pursuing any serious personal relationships in his life, but also one that would spur him on to his successes in Hollywood.

As Keanu settled into life in Los Angeles, more work followed Under the Influence. In the Home Box Office effort Act of Vengeance (1986) he played opposite Charles Bronson as a ‘psychotic assassin’ (foreshadowing his later comedy role in Lawrence Kasdan’s I Love You to Death). The John Mackenzie-directed TV movie was based on a true story and had Bronson (minus his trademark moustache) as a union member whose challenge for the leadership leads to his family’s murder. Young novice Keanu was in good company, as the film also featured Ellen Barkin, Wilford Brimley and Ellen Burstyn.

John Mackenzie recalled Keanu as being difficult to work with, although the problems seem mainly to have stemmed from the young actor’s inexperience of movie sets and the process of film-making. Mackenzie had cast Keanu in the role as he saw something ‘off-the-wall’ in the actor’s own personality. He wasn’t too pleased, however, when this very quality came across during Keanu’s work on the film. He was clumsy during scenes and annoying to Mackenzie, who called the actor ‘an upstart’. Speculating that Keanu’s behaviour may have been down to drug-taking, Mackenzie set things right by giving the actor a severe dressing down. It was an approach that worked, and he was to watch his Ps and Qs for the rest of the shoot. It was the first, but not the last time that Keanu was to be perceived as ‘difficult’ by one of his directors.

Finding himself constantly busy on films, Keanu had little time to pursue a life away from movie sets. Act of Vengeance was followed up with a leading role in The Brotherhood of Justice, another TV movie with a message. Keanu played Derick, a rich kid on the make who drives around in a flashy red sports car and has no problem drawing a group of girls around himself, an attraction no doubt helped by his captaincy of the football team. It was the ideal teen role for Keanu, a chance for him to stretch his wings by taking on a more central part in a drama. He was also playing a bad guy, as his seemingly all-American kid becomes the head of a vigilante gang that starts off meaning well but quickly gets out of control. Kiefer Sutherland played the high school do-gooder with whom Keanu’s over-the-edge character clashed.

With both Variety and the Los Angeles Times having commended the young actor’s performance in Under the Influence, reaction to The Brotherhood of Justice came as something of a disappointment. The Los Angeles Times was particularly unimpressed, pointing out that as Keanu’s eventual doubt about the gang’s activities ‘weighs less heavily on him than the distress of losing his girlfriend, it hardly makes for compelling viewing’. As he continued the rounds of auditions, he won more teens in the family roles in TV movies-of-the-week like Moving Day, made as part of the Trying Times teen series for the PBS network.

Despite his work rate, it was pointed out to Keanu by his managers that his unusual name was in fact getting in the way of him winning roles. ‘That was a terrible, terrible phase that lasted about a month,’ recalled Keanu about his brief flirtation with changing his unusual, but real, name to something more ‘Hollywood’. ‘I was informed that my manager and my agent at the time were having trouble getting me in to see some casting agents because of my name. It had an ethnicity to it that they found was getting in the way. And so they said I had to change my name. That freaked me out completely. I came up with names like Page Templeton III. And Chuck Spidina, from my middle name, Charles. Eventually they picked K.C. Reeves. Ugh, terrible. When I would go to auditions, I’d tell them my name was Keanu anyway.’

William Goldman once claimed that no one in Hollywood knows anything, and it is ironic to note that while the feature film industry recognised in Keanu Reeves’s almost ethnic, vaguely Chinese or Asian good looks a star in the making, his name on its own served to block him from roles, for the very same racial reasons. The concern of his managers was apparently misplaced, as Keanu he was to stay.

As a jobbing actor, Keanu found many scripts coming his way and opportunities for auditions before him, but as the new kid on the block he had to resist the strong temptation to be too picky about what he chose to do. ‘I want to be enlightened, dude,’ he claimed. ‘I [want to do] interesting stories, interesting people, character development, ideas being posed, clash/conflicts, hate, love, war, death, success, fame, failure, redemption, salvation, death, hell, sin, good food, bad food, nice smells, colours and big tits.’

Some, but not all, of those elements were to be found when he co-starred with a young Drew Barrymore in Babes in Toyland, an ill-advised and overlong TV version of the Victor Herbert operetta, which featured a new score by Leslie Bricusse. Directed by Clive Donner and clocking in at slightly over two and a half hours, Babes in Toyland retained only Toyland and March of the Wooden Soldiers from the original score to punctuate the screenplay by Pulitzer prizewinner Paul Zindel. Also in the cast were Richard Mulligan and Pat Morita (later to feature in Even Cowgirls Get the Blues).

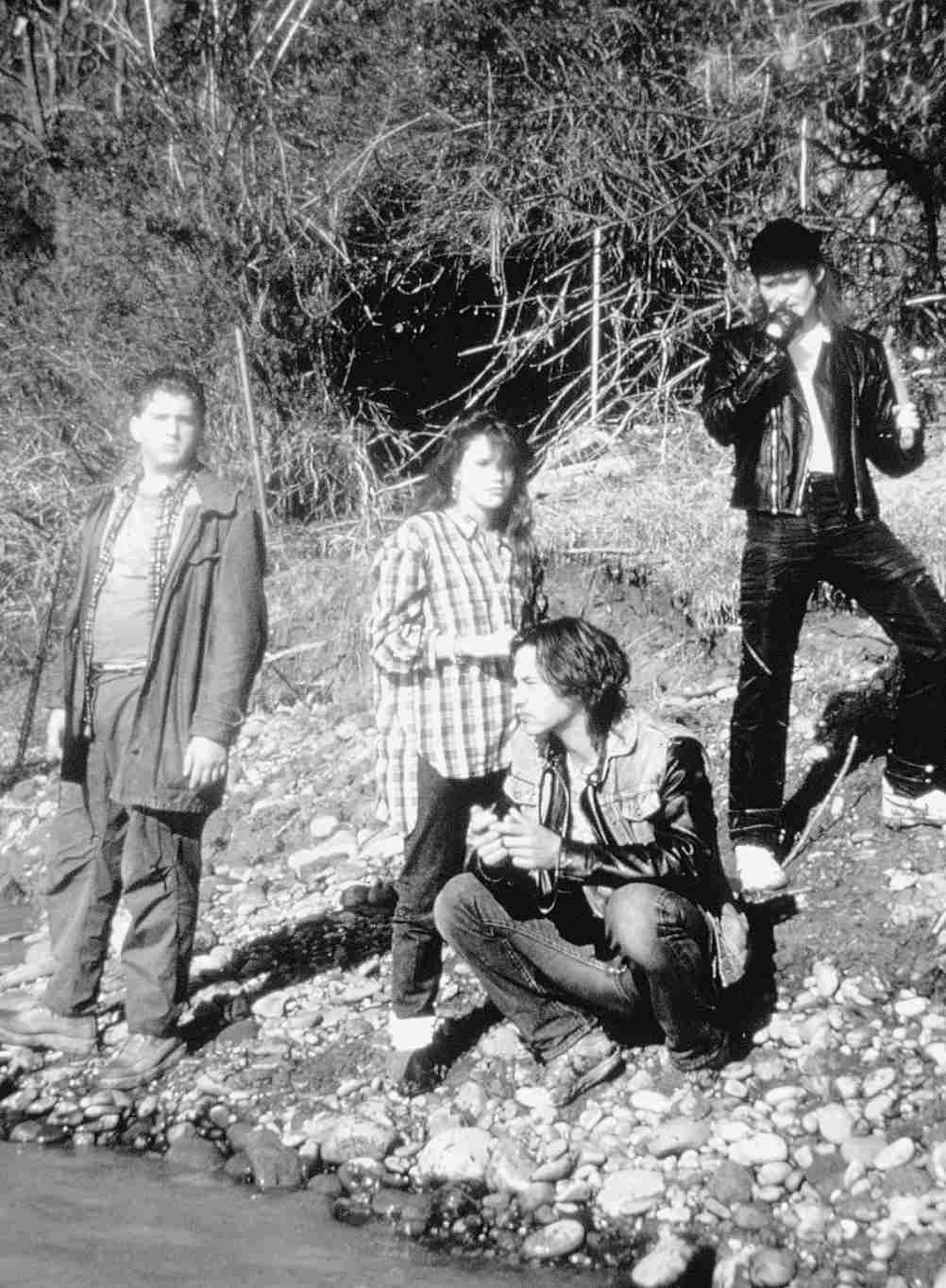

Keanu co-starred with Lori Loughlin (centre) and Kiefer Sutherland (right) in the TV movie Brotherhood of Justice.

The TV movie did give Keanu his first film-related trip abroad, to the Bavaria Studios in Munich, Germany in July 1986. The tight, 33-day shoot was simply not enough time for director Donner to do justice to the source material, and the finished broadcast version showed every sign of having been a rushed job. Keanu played the boyfriend of Barrymore’s older sister in the real world, and Jack Nimble in the fantasy land into which Barrymore finds herself pitched. With Barrymore in tow he endeavours to overthrow the evil Barnaby Barnacle who plans to take over Toyland. The key to defeating the evil villain was to have Barrymore reaffirm her belief in the fantasy of toys and make-believe. Dancing and singing, Keanu made the best of a difficult part.

Broadcast just before Christmas in the United States, critics leapt upon the production’s inadequacies with a vengeance. The New York Times accused the cast of being on ‘automatic pilot’, while USA Today simply described Babes in Toyland as ‘painful to behold’. Luckily enough, none of the criticism stuck to Keanu.

There was one personal benefit for Keanu in taking on the role in Babes in Toyland. He enjoyed his first film-set affair with co-star Jill Schoelen, who played his on-screen girlfriend. The brief affair seems to have been treated almost as a holiday romance by Keanu. Schoelen, however, seems to have made a habit of serious involvements with her co-stars. A year later, while making the 1987 horrorcomedy Cutting Class, Schoelen was to enjoy a three-month liaison with rising heart-throb Brad Pitt.

As his work increased in frequency, Keanu found that getting into and out of the parts he played became second nature, even if there was a minor downside. ‘The first two weeks after I’ve wrapped a movie, I’m out in space,’ he said. ‘I can’t speak about anything.’

All this work, even if much of it was in second string roles as the boy-next-door, or as a family member only ever seen at the breakfast table, was great experience for Keanu. He realised he was on a learning curve and used this period of his career to his best advantage, managing to sample a variety of teen roles, still playing on screen well under his actual age of 22 years.

‘All I can say is that I try to give and I try to learn,’ said Keanu of his approach to these early roles. Asked in an interview about the best aspects of fame, he was nothing if not realistic about his status in 1986 in a Hollywood crowded out with would-be hot young actors. ‘I almost said chicks and sex and fucking and money – but that hasn’t happened yet. What do I like most about being an actor? Acting! The best thing for me about being an actor is acting. I mean, what else is there?’

‘What else is there’ was also a question to be asked about the young actor’s offscreen life. Although extremely busy as a jobbing actor making his way in Hollywood, Keanu was also trying to fit into the social life of LA. Having set up in his own apartment, Keanu was finding his feet in a city that he didn’t know very well, but did soon feel at home in. With his first income from his handful of movie roles, Keanu had switched his Volvo for a motorbike, and he took to exploring the hills of LA, sometimes late at night. Having left school far behind, Keanu took up reading as a hobby, turning his attention to anything from popular fiction to classics of literature or scientific textbooks. When not acting, he made a point of trying to keep his mind busy by sticking his head in a book and absorbing the knowledge he’d missed during his years of playing up at school.

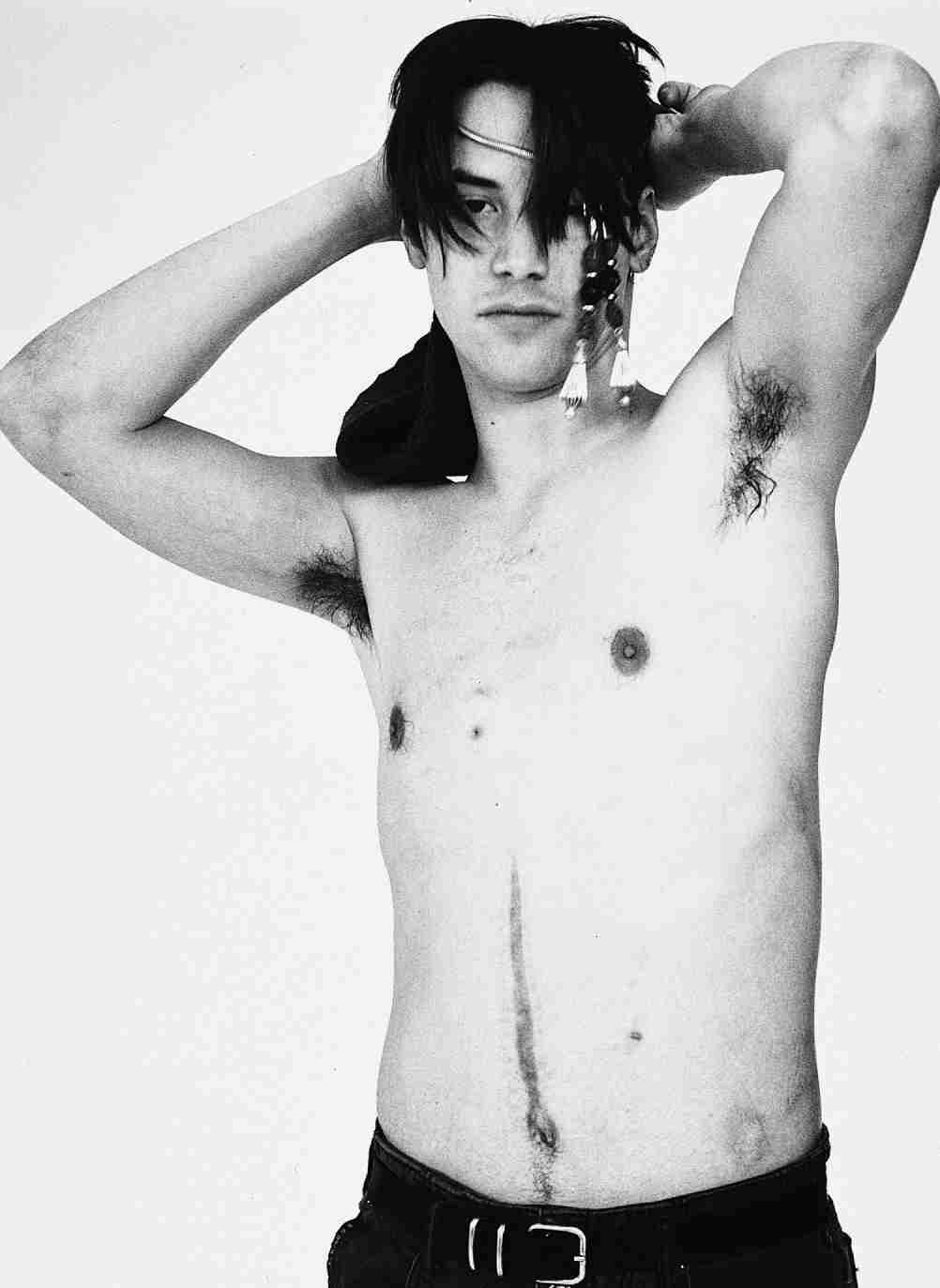

Mean and moody: in River’s Edge Keanu played a darker teen rebel.

Everything was about to change for Keanu when he won the role of a seriously troubled teen in River’s Edge.

Based on a shocking true story which took place in Milpitas, California in 1981, River’s Edge was the first significant scriptwriting work by disabled writer-director Neal Jimenez, later to make his mark with The Waterdance (1992). The story of the rape and murder of fourteen-year-old Marcy Conrad on a seeming whim by her sixteen-year-old boyfriend Jacques Broussard fascinated Jimenez, who was then a film student in San Jose. He used the story of Broussard bragging to his friends and displaying the corpse to them as the basis of a set project for his screenwriting class. Although his script was not welcomed by his tutor, who felt it was too dark, it did spark interest among the studios. After consideration, though, most backed away from the obviously bleak subject matter, seeing it as being too controversial for a mainstream film. Jimenez’s saviours came in the form of British film company Hemdale, behind the financing of such controversial American films as Platoon, At Close Range and Salvador, who soon had the project in production as a low budget film to be directed by Tim Hunter.

The film opens in the aftermath of the murder, as teenager Samson smokes a joint next to the naked dead body of his girlfriend, Marcy. Unknown to Samson, he’s been seen, by Tim, the twelve-year-old brother of Samson’s pal Matt (Keanu Reeves). Getting involved with the older boys, Tim is soon introduced to Feck, the boy’s one-legged, ex-biker drug supplier (played by ’60s icon Dennis Hopper). The story of Samson’s actions soon spreads throughout the school as pupils trek to the river’s edge to see the body over several days, without going to the authorities. As the repercussions spread, Matt eventually decides he has to inform the police, but they can’t prevent Feck from visiting his own brand of eye-for-an-eye justice on the amoral killer Samson.

Hunter chose an eclectic cast to bring the bleak tale to life. Switched from sunny California to America’s cold Midwest, Hunter ensured that the setting matched the subject matter. He wanted to do the same with the casting. He signed up Dennis Hopper, who was then in a rut in his career for the character role of Feck, and eccentric rising actor Crispin Glover (Back to the Future) as a key gang member. Keanu Reeves was cast as the only character in the film who begins to see the fact that the activities of the teenagers are wrong, and he finally admits all to the authorities.

Director Tim Hunter tackled this $1.7 million budget project almost as an anti-teen movie, certainly an anti-John Hughes movie. Hughes had made something of a name for himself writing and directing a series of feel-good teen movies starring the so-called brat pack, including such films as The Breakfast Club (which Keanu had auditioned for, but failed to win a part in), Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and St Elmo’s Fire. Splicing ’60s values, through the Dennis Hopper character, with ’80s nihilism, Hunter called the film ‘a combination of the mundane and the surreal. That makes it an unusually tough film to get a handle on and watch from a comfortable perspective.’

Although not altogether happy with his work, Hunter was pleased to have been able to take a different perspective on the clichéd genre of the teen flick. ‘River’s Edge is far from perfect. In some ways it isn’t even successful. But what I like about it is that so many teen movies that are social-issue oriented tend to skirt their own issues. Whereas these kids are dealing with the implications of this event from the minute they see the body, and they never get away from it. There’s no bullshit – they’re working it out through this picture.’

At the river’s edge: Keanu and his co-stars contemplate their seemingly bleak future.

Ahead of its time in its nihilistic bleakness and refusal to conform to Hollywood’s desire for happy endings, River’s Edge failed to set the American box office on fire. After previews in Seattle in October 1986, the film gained good reviews from critics, but failed to draw in audiences. With Hemdale in financial difficulties, it was left to film festivals in Europe to promote the unusual project to potential audiences.

Of the critics writing about the film, Vincent Canby in the New York Times was the most positive about River’s Edge, singling out the character of Matt, as played by Keanu Reeves. ‘River’s Edge is the year’s most riveting, most frightening horror film . . . To the extent that River’s Edge has a sympathetic character, he’s Matt (Keanu), the young man who finally does call the police, but who, when asked to explain why it took him so long, is genuinely baffled. “I don’t know,” he says. The unbelieving cop asks him what he felt when he saw the body of the girl, someone he’d known since grade school. Matt, furrowing his brow, replies, “Nothing.”’

Richard Schickel, writing in Time, also saw Keanu’s Matt as central to the film. ‘Matt, who is played with exemplary restraint by Keanu Reeves, does finally violate their conspiracy and makes a tentative connection with traditional morality. But by this time the cold of this brave and singular work has seeped into our bones, we know that Matt is the exception to a bleak and deeply disturbing vision of adolescent life.’

Fans of Keanu may have noted the strong connection between Keanu’s real life as a decent kid without a father and this role. David Denby in New York magazine wrote: ‘The one who finally breaks away and goes to the cops, Matt (Keanu Reeves), is a decent boy struggling for clarity. Like the others, Matt lives in a squalid, trailer-trash house, with harassed, overworked adults. His own father had vanished, replaced by a noisy, exasperated lout; his mom, a nurse, is worn out. All the kids have grown up in a vacuum, without any models, any authority they can respect.’

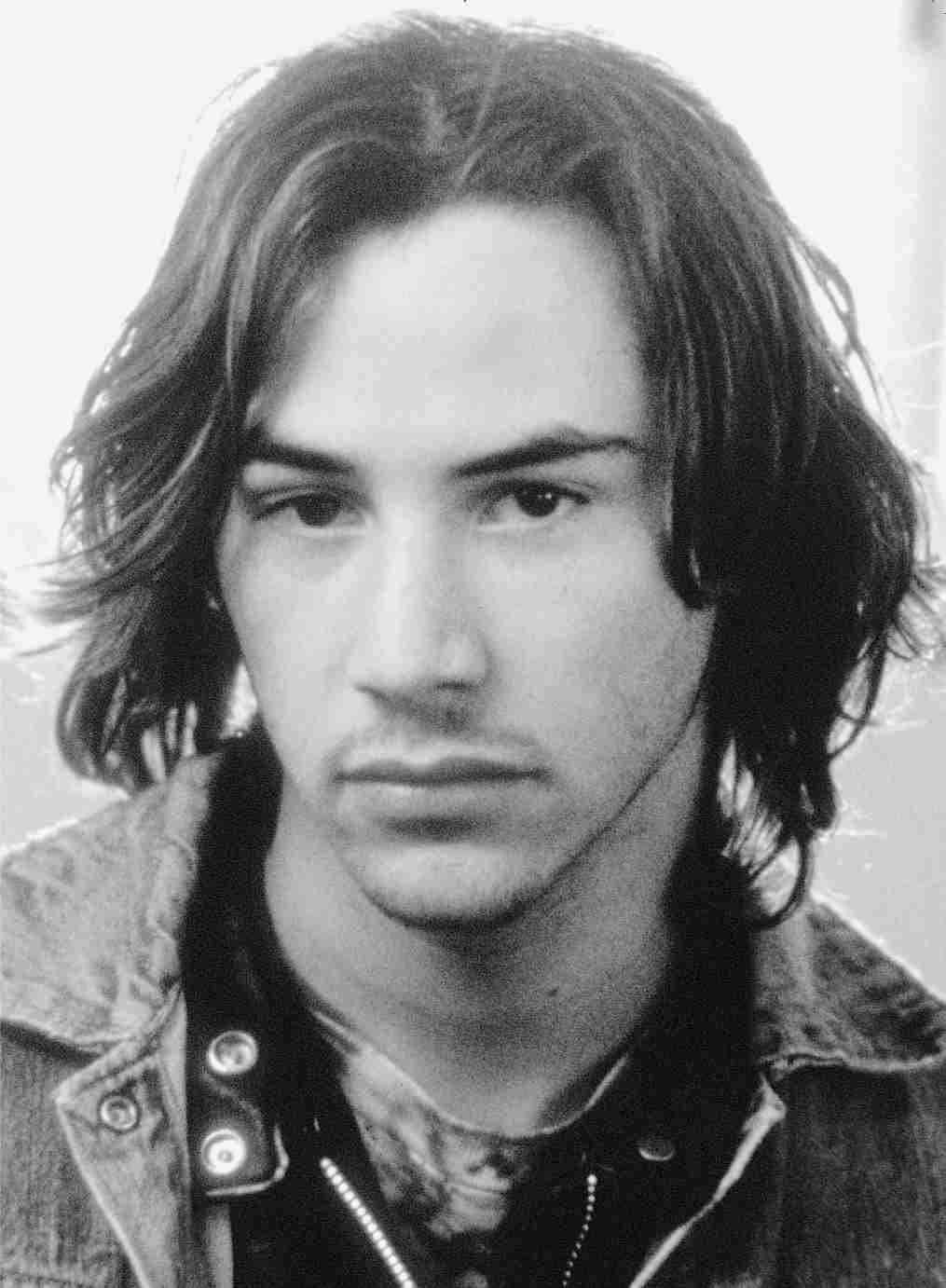

Keanu and Ione Skye Leitch in River’s Edge.

Indeed, it was only later that River’s Edge would really find its audience on video, becoming something of a celebrated cult movie in the process. Audiences may not have seen the film on its first release, but movie directors who were later to work with Keanu Reeves were to cite River’s Edge as the first film which had brought the young actor to their attentions. He’d finally made it in Hollywood, even if he’d not yet clicked with movie audiences.

Some kids were deeply affected by Keanu’s performance as Matt, as he recalled: ‘Only one really heavy thing has happened to me. Once I met a kid who was seventeen and he dressed up like Matt, my character in River’s Edge. He told me I was his idol, and he gave me loads of free food from the restaurant where he worked.’

Keanu himself seemed to realise that he was on the road to success, and he began to worry about its potential effects on him. In an early interview he connected his increasing visibility with his possible religious beliefs. ‘I seem to pay some petty respect [to God] whenever I talk about my success. I talk about my fear of retribution for my success – that I must pay for it. I guess in some sort of deeprooted way, I feel I haven’t. I guess I’m paying tribute to irony. Irony can make you bitter, but, yeah, I guess I believe in God. No, I don’t believe in God. I don’t know. These things are still in turmoil.’

Partly through failing to win a part in ‘brat pack’ movie The Breakfast Club, Keanu Reeves had narrowly escaped being lumped in with that infamous group of young ’80s actors which included Andrew McCarthy, Rob Lowe, Demi Moore, Emilio Estevez, Molly Ringwald and Ally Sheedy. It was something he was grateful for, eventually. He was glad he wasn’t part of an identifiable trend in young Hollywood actors.

‘This is what I feel is happening with actors in Hollywood,’ explained Keanu. ‘A lot of people I’ve been working with have a sense of darkness and seriousness about their point of view of acting. I think there are a lot of heavy actors who are going to come out and surprise people. They are going to help Hollywood. They are very sincere and generally well-read and smart about what they are doing. They have a strong point of view about their acting and their place in the world. We are getting more theatrical in our acting styles. Film in that sense is taking more risks. Even the actors who aren’t doing anything yet but being cute and themselves will, hopefully, in the future push and expand their limits. We hope – because I’d like to spend six bucks and feel it was worth it.

‘I’m not Dennis Hopper; I’m just doing what I’m doing – trying, at least. I’m trying to pursue what I’m curious about, trying to survive, and hopefully not be fucked up the ass by irony and the gods.’

Deciding where his ambition lay, Keanu had a hankering to make a bizarre, offthe-wall comedy. ‘People are bored with being so literal. We need some more of that good old thirties, forties and fifties surrealism again, especially in our comedy. Audiences are ready to see more intelligent work.’ Before that, though, Keanu had more teenage roles awaiting him, although he was now in his mid-twenties. He also had his first costume drama to tackle, as well as a near-fatal motorcycle accident that almost stopped his film career in its tracks.