AT THE TIME of his greatest triumph on screen in Speed, and having managed to shake off the ludicrous rumours connecting him romantically with David Geffen, further trouble hit Keanu Reeves. His father, Samuel, whom Keanu had not seen since his teenage years, was arrested in a blaze of publicity at Hilo airport in Hawaii. The charges related to serious drug-trafficking offences, as Samuel had been caught in possession of large amounts of cocaine and heroin, and was accused of having dealings with a major Mexican drug-smuggling gang.

Police had been on Samuel’s trail for weeks, keeping close watch on the rotund middle-aged man and his farmhouse in Hilo. Based on a tip-off from a neighbour, the undercover cops followed Samuel and a companion to the local airport where they finally pounced, grabbing the pair with a consignment of heroin and cocaine.

Arrested with Samuel was Hermilo Castillo, 24, said to be a member of a Mexican crime family. Castillo promptly put up $100,000 bail and immediately skipped the country, leaving Keanu’s father alone to face the music for smuggling ‘black tar’ heroin onto the island.

Appearing in court on 21 June 1994, Samuel Nowlin Reeves accepted his guilt on a reduced charge of ‘promoting a dangerous drug in the second degree’. His arguments that drugs should be legalised and that he was doing no harm, combined with his past record relating to drugs, had served to curse Samuel Reeves. A ten-year sentence in Halawa State Prison, near Pearl Harbor, was the result.

Although he was estranged from his long-absent father, it was clear to Keanu that he could not escape the fall-out from his father’s jailing, even if he wished to pretend otherwise. ‘I don’t want to talk about him,’ was the standard response from Keanu to press questions. ‘He disappeared out of my life when I was a kid.’

Despite his evasion and his determination to avoid talking about his father, it was clear that Samuel had been a major influence on the life of Keanu, largely through his absence. ‘I think a lot of who I am is a reaction against his action. [As a father] I would, first of all, try to be around.’ Shy and lonely as a child, Keanu had never recovered from his abandonment by his father at the age of thirteen. Despite his superstardom, thoughts of his father could easily push Keanu back to the feelings that dominated his teenage years – and now at the height of his success, his father had come back to haunt him with a vengeance.

Although Keanu kept quiet about his father’s arrest, his cousin, Leslie Reeves, was happy to speak out on the star’s behalf. ‘When he heard his father had been arrested, Keanu was angry. He said, “Who the hell needs this?” He does not love his father. He has nothing but contempt for him. He hates him.’ Added Keanu’s childhood pal, Shawn Aberle, ‘He really resented the way he felt his father had abandoned him.’

Yet it was that abandonment that drove Keanu to show he could do better than his father before him, and despite his fortune and the fact that he lived and worked amid countless temptations in Hollywood, he was determined to avoid the traps of drug addiction. He had seen how that lifestyle had ended up for both his actor friend River Phoenix and for his now jailed father. They were mistakes Keanu Reeves was determined to learn from.

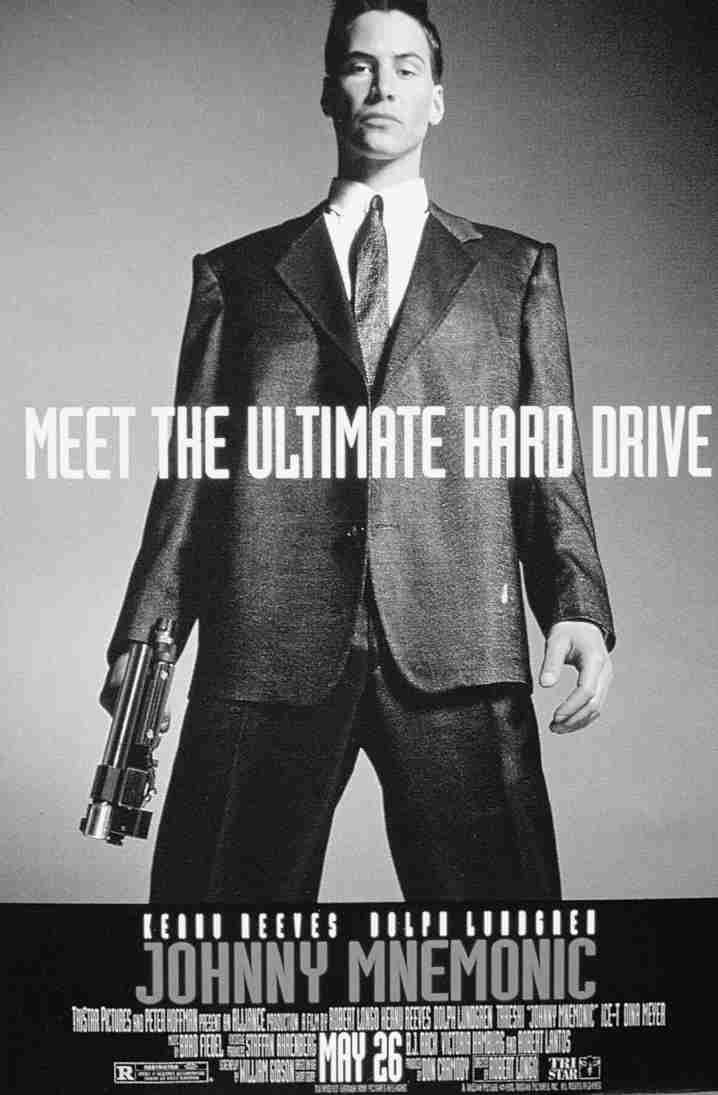

The original source material for the film Johnny Mnemonic was a short story by renowned ‘cyberpunk’ author William Gibson. Gibson coined the concept of ‘cyberspace’ in the early 1980s (‘They’ll never let me forget it’), long before the Internet became the phenomenon it is today. Although he started writing science fiction in 1977, Gibson is still best known for his trilogy of Neuromancer, Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive, published between 1981 and 1988. Neuromancer brought Gibson the Hugo, Nebula and Philip K. Dick awards, as well as acres of mainstream press coverage.

Originally, Johnny Mnemonic was set up under the auspices of Carolco Pictures, but due to financial difficulties the property was put into ‘turnaround’, meaning it was available to be picked up by another studio or producer once they’d paid off Carolco’s development costs to date.

Ice T, Keanu and Dina Meyer in Johnny Mnemonic.

The project was picked up by an ex-Carolco producer and Gibson fan Peter Hoffman, who hired Terminator 2: Judgement Day and Total Recall producer B. J. Rack to ‘midwife’ the project into existence. The proposed director was artist Robert Longo, a fixture of the New York avant garde art world. In the so-hip-it-hurt cast were post-punk performer Henry Rollins, rapper Ice T and Japanese cult figure ‘Beat’ Takeshi Kitano.

Before Keanu Reeves landed the part, Val Kilmer was originally signed to the title role of Johnny Mnemonic. ‘I had some conversations with him about the role,’ said Gibson of Kilmer. ‘Then I woke up one day and, lo and behold, he wasn’t in it. I think Val could have done a very dramatic job, but it would have been different. That’s the strange thing with casting, it can really change a movie.’ Kilmer’s PR people told Premiere magazine: ‘Val did everything possible to resolve creative and financial differences, but they never were, so he left.’

The intrigue of the cast change extended to how the script found its way to Keanu Reeves. The actor didn’t get the script through his agency Creative Artists Agency (CAA), which also represented Kilmer and may have recognised a conflict of interests. ‘It arrived on my doorstep,’ insisted Keanu. ‘It was given to me by a friend of a friend. When I saw William Gibson’s name on the credits, I was like, “Cool.” I had read Neuromancer when it came out, and I was a great fan of it. I said, “Yeah, I’d like to work on this.”’

In fact, the script was sent to Keanu through a drive-by delivery, tossed into his yard from a passing car. Keanu was not a sure-fire action star, as he was in production on Speed at the time, so TriStar executive Chris Lee had a tough time convincing the studio that he was the right guy for the part. Keanu was also going to be a more expensive option than Kilmer, his asking price being in the region of $1 to $1.5 million per film before the release of Speed, resulting in TriStar putting up the additional money in exchange for the video distribution rights to the finished film.

The casting of Keanu Reeves was the final element that allowed Gibson to bring his title character fully into focus. ‘In the beginning he’s a slick, superficial, robotic asshole. As he bumps into more and more terrible immovable objects, the surface starts to crack, and underneath is this vulnerable human being. Keanu gave me real crucial help in figuring out this character, because people were always saying, “We don’t get the motivation on this guy.” Keanu asked me early on where this guy was coming from and what’s he really like, and I’m like, “I don’t know.” That was the beginning of his interpretation of the character. It was utterly crucial that he developed those wonderfully subtle, robotic twitches and ways of moving.’

Keanu was only too aware of the casting musical chairs and the actor had concerns about the script, which he talked over with Gibson and Longo. ‘The film in its final incarnation is so different from where it began,’ he admitted. ‘I play the title character who has the capacity to store computer data in his head. In order to have that capacity, I’ve had my long-term memory, mostly dealing with my childhood, removed. My character didn’t care that he’d had his memory erased.’

Keanu felt this disinterest in the character’s background was a mistake, and his concerns resulted in Gibson and Longo altering the dynamics of the Johnny Mnemonic script. ‘They decided to make it so that he does care, so the whole journey of this hero is to regain his childhood.’

The plot of Johnny Mnemonic has Johnny transporting some valuable information in his head. But now, Johnny wants out and he goes on the run with the information and his female bodyguard. In pursuit are various parties all interested on getting their hand on the data in his head. Additionally, he must download the information within a set time scale, otherwise his brain will overload and go pop! Journeying through a nightmarish technological future, the mismatched pair find themselves in ‘heaven’, a low tech hide-out for society’s technological underclass.

Tackling the multi-faceted role was something of a challenge for Keanu, after the straightforward heroics and running and jumping of Speed. ‘I was really dealing with an unconscious anger for this character,’ he said. ‘There was a level where I worked with Robert [Longo] on the angularity of the character. He was hard-edged. He’s not the nicest guy in the world. His job demanded a kind of aggressiveness, in terms of controlling a room and making sure of his safety. When I get uploaded with the data, I’m at such a disadvantage. I’m unaware of everything around me, and it’s kind of a shady business that I work in.’

Coming off Speed, taking on the relatively low budget production of Johnny Mnemonic was a different experience for Keanu. ‘I call it a big budget, low budget picture. We didn’t have a long shooting schedule so that put quite a demanding pace to the filming, which I dug. It had its good and bad aspects. It makes you pare down and be aggressive in a different way, but sometimes it does induce more compromise. Robert had some quite unique cinematic ambitions which were not allowed to be explored because we didn’t have the time or the money to do that.

With a novice director – a painter no less – handling a $30 million film, with a script from a heavily involved writer who had no real movie experience and a last minute replacement for the leading actor, Johnny Mnemonic was fated to be not without its problems. Many seemed to stem from Robert Longo’s inexperience in organising the hundred or so people that make up even a small film crew. According to some on the set, whenever Longo issued an instruction some warweary members of the crew would whistle the tune ‘If Only I Had A Brain’ from The Wizard of Oz. According to others, Longo was at times overwhelmed by the enormity of the project and so lacked the authority to control the complex production.

Canadian producer Don Carmody, one of the people who rode to the rescue of the film when Val Kilmer left, was detached enough to get to the heart of the problems. ‘Robert’s a first-time director and he’s got a lot of ideas, but he doesn’t always know how to implement them. He gets to try things out on me first. If we’re running late, I’ll pull rank. We have some difficult personalities . . . Keanu can be moody . . .’

Observers on the set of Johnny Mnemonic felt Keanu came across as a little reserved, if not downright quiet during the dramatic production process. ‘Because of the rigorousness of the shooting schedule and the pace, I really had to conserve my energy. I had just filmed Speed and that was very vigorous as well. I was saving my energy for when I had to work. It’s not a Die Hard or anything in that genre, but there was some running and jumping and dodging bullets. I enjoy that kind of physical work.’

For twelve weeks the cast and crew were located in Toronto and Montreal, shooting on sets constructed to stand in for Beijing, China and Newark, New Jersey, all locations in the film’s 21st century story. Production designer Nilo Rodis had limited resources to create a future vision to rival that of the 1982 film Blade Runner – a future dystopia from Philip K. Dick, realised by director Ridley Scott and often mentioned in the same breath as the ideas of William Gibson. Rodis had to draw on his experience in industrial design and car engineering to come up with the high- and low-tech future of the film.

Keanu with Henry Rollins in Johnny Mnemonic: his character can store computer data in his head.

Gibson, for one, was impressed by Rodis’s efforts. ‘I realised that for thirteen years I’ve gone on describing environments like this, and I never expected to see one realised to this degree of resolution. Especially the set for heaven.’

Most critics, however, were not impressed by Johnny Mnemonic. For the Village Voice, Keanu was ‘terrific except when he opens his mouth – and what a great haircut’. The New York Times accused Keanu of ‘robotic delivery’.

‘When my life is over, I’ll be remembered for playing Ted,’ claimed Keanu once, outlining one of the fears that drove his career after Speed. Determined to shake off the airhead image that had shot him to fame once and for all, he didn’t want to fall into another trap of playing nothing but action heroes – as he’d just done in Speed and Johnny Mnemonic. Variety was the spice of his acting life – and he knew his devoted audiences wouldn’t necessarily like it.

It wasn’t that Keanu was ungrateful for his film success, particularly his newfound fame and wage bracket after Speed. He felt capable of much more. ‘I did a pretty good job,’ he said of Speed, ‘and it’s there on the screen, but I don’t really feel like it’s my film. I mean, it was great to be in such a successful film, but I don’t know how much of that success is down to me. . .’

Keanu continued to be secretive about his off-screen life, denying that he’s part of the Hollywood industry or the party scene. ‘It gives me a living, but. . .I must admit I’ve never been very “industry”. I don’t have enough of a personality. It’s true – I lead a very simple and small life. I do go out. I have visited that scene once in a while and I have enjoyed it. I’m always working anyhow.’

When not working on films, though, Keanu professed not to get up to anything special. ‘I sit on the couch and indulge whimsies. My current whimsies are coming home, talking to friends and taking voice classes. I do go out once in a while, it’s not like I’m a monk.’

This vagueness in Keanu’s pronouncements about his off-screen life infuriated his fans, who relied on those who knew him well enough to fill in the many blanks that the star himself left. ‘It’s interesting,’ admitted Gus Van Sant, who’d worked with Keanu twice, ‘Keanu’s well-read, but he doesn’t think he is. And he’s very intelligent, but he’s a sort of punk rocker, in a way, and he has this façade.’

Part of his façade has been to appear to do nothing with the money he makes. Despite his asking price shooting up to $7 million after Speed, he still had no home of his own, with many of his possessions in storage at his sister Kim’s home. ‘I guess I’m just looking for the right place to live. It’s not like I’ve got this gypsybohemian philosophy like, “I don’t want a home because I don’t want roots.”’ From hotel to hotel and film to film, Keanu carries with him just one suitcase filled with necessary items. ‘I’ve got it pretty pared down,’ he says, claiming only to carry a couple of pairs of trousers, a few T-shirts, socks, underwear, one suit, a sports jacket and a pair of shoes. His only other possessions of any consequences are his two motorcycles and his guitar. So what does he do with all that money, then?

Dina Meyer and Keanu in Johnny Mnemonic.

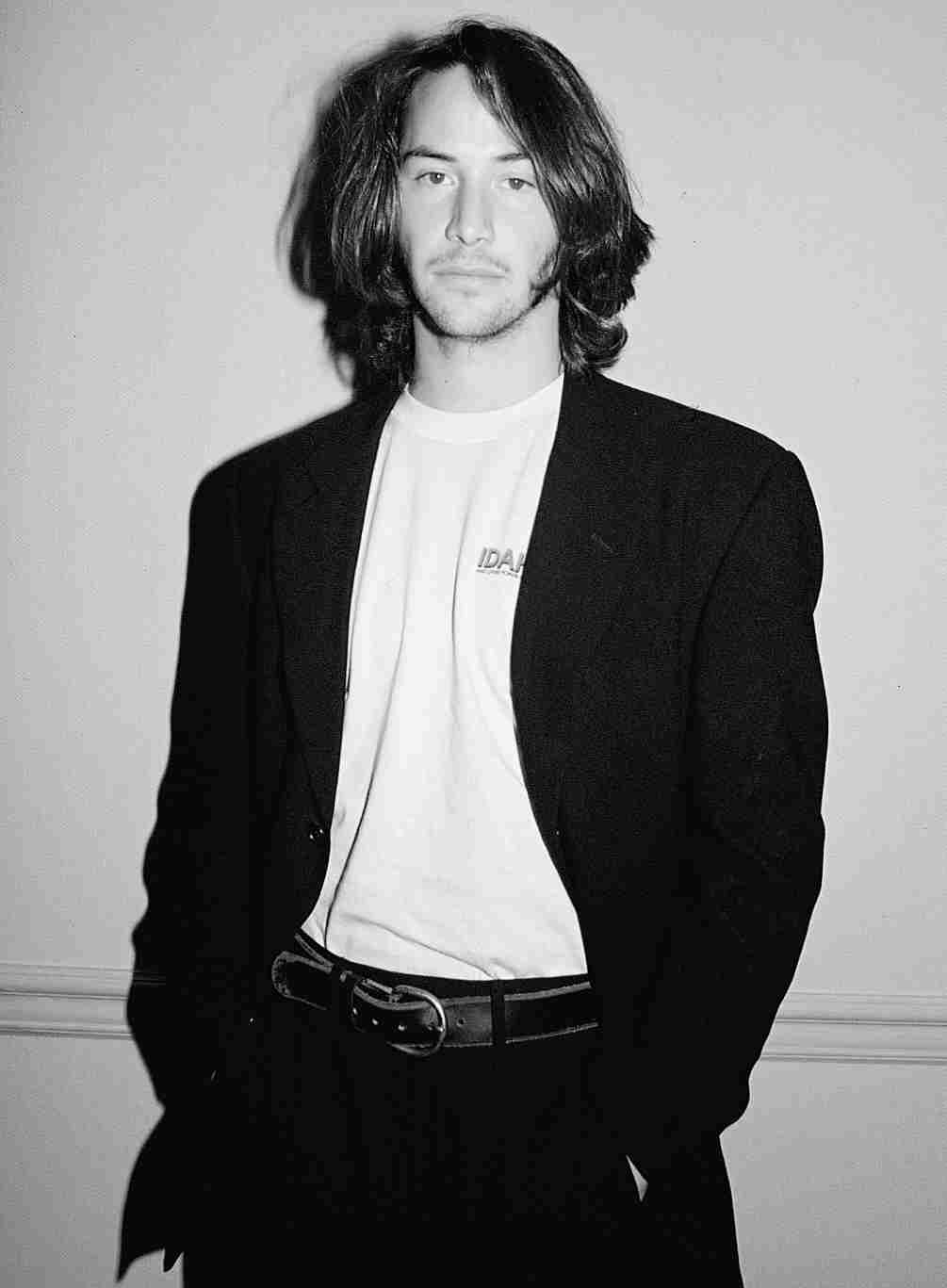

Keanu in A Walk in the Clouds; his first true romantic lead.

‘Ah, what do I do?’ responded Keanu to the question in Vanity Fair. ‘It affords one a certain amount of freedom and travel and I can buy older Bordeaux. I can afford my two Nortons, which is akin to sending a child to a middle-expensive university in the US. But the travel is great.’

Despite his wealth and fame, the biggest concern Keanu has is to project the fact that he’s just a normal guy. ‘I am normal. Any other kind of perception is a lie, and it just leads to . . . madness. I’m just very grateful to have the opportunity to work, and I’m grateful for people who like it, and so I’m paying respect, as much as I can.’

‘I don’t want to be super-famous, man,’ Keanu said to New York’s Newsday in 1991. ‘That would be awful.’ Awful or not, super-famous and a sex symbol is just what he’s become following Speed. ‘I hate that term, “sex symbol”. I don’t think I’m a sex symbol and I don’t think I look like one either.’

His Johnny Mnemonic co-star Dina Meyer had definite opinions about Keanu’s sex symbol status – and about his inner darkness. ‘He thinks he’s a nerd! I couldn’t believe it. He really thinks he’s just some schmo off the street who loves to act. He’s very quiet, very introverted,’ Meyer told People magazine. ‘You look at him and can see the wheels turning, but you can’t figure him out – if he’s happy, if he’s sad. . . you just want to say: “What’s happening in there?”’

Avoiding talking about his personal life and thoughts was a skill Keanu had cultivated over the years, from first playing the part of Ted in interviews to throw journalists off the scent to later simply restricting his comments to the film he was promoting. ‘I think everyone has an inner core they protect – I don’t think I’m any different really,’ he admitted. Keanu Reeves went from an action movie double whammy in Speed and Johnny Mnemonic to his first straight romantic lead in Alfonso Arau’s A Walk in the Clouds.

Arau had been behind the surprise hit Like Water for Chocolate, a steamy tale tinged with a degree of magical realism. His new film told the tale of an American GI returning from war only to become embroiled in a family drama in ’40s California. Arau knew he wanted Keanu to play the sensitive GI.

‘I said “You can play a very romantic character if you want,”’ remembered Arau, feeling that Keanu had the sensitivity for the part, but also had to lose some of his innocence. ‘I said, “Keanu, you are going to have to interpret as a grown man, as opposed to an adolescent.” You can feel that he has all these emotions below the skin, so I had to open the door for him.’

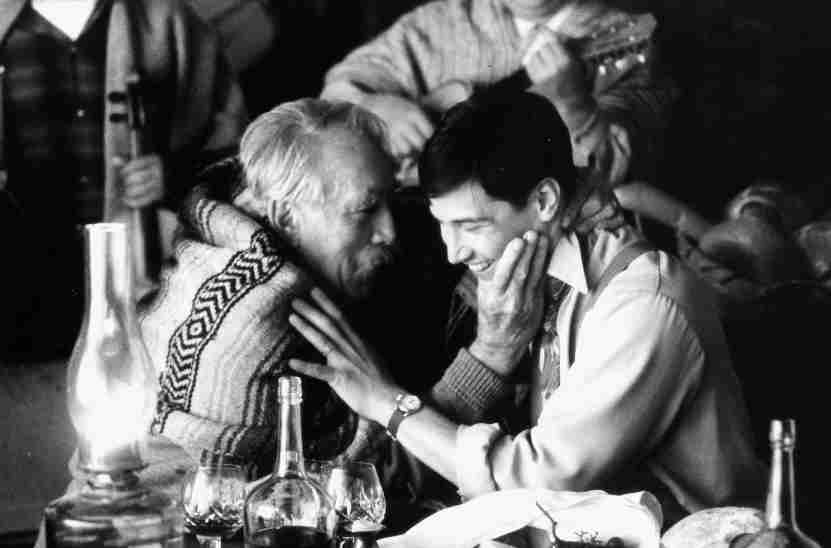

Based on an Italian film called Four Steps in the Clouds and directed by a Mexican film-maker, it tells the story of Paul Sutton (Keanu), a soldier who has had his fair share of hellish experiences. Back home and selling candy on the road, he comes across a distressed woman named Victoria (Aitana Sanchez-Gijon) returning to her family home in the Napa Valley. Dumped by her boyfriend, Victoria is pregnant and unmarried, a scandal in 1945 America. Sensitive shell-shocked soul that he is, Keanu’s Paul offers to stand in as her husband to smooth her return home and her relationship with her domineering wine-growing father, played by Anthony Quinn. Of course, the best laid plans can result in the most unexpected outcomes.

A Walk in the Clouds saw Keanu working with Aitana Sanchez-Gijon and Anthony Quinn.

Romance in the air: Keanu and Aitana Sanchez-Gijon in A Walk in the Clouds.

For Arau, Keanu was the most suitable actor for this Gary Cooper-inspired ordinary Joe. ‘Keanu is like a monk,’ he asserted. ‘He is devoted to his craft, and has an innocence in his spirit that I liked for this particular character.’ Screenwriter Robert Mark Kamen was in full agreement with his director. ‘Keanu is incredible. He’s romantic, he’s sensitive, he’s nuanced. It’s Keanu like you’ve never seen him before. . .’

That much at least was true. When Keanu accepted the role in A Walk in the Clouds, his action hero debut Speed had not yet been released. Johnny Mnemonic had not yet bombed. For Keanu, playing an adult romantic lead was something of a radical departure. The nearest he’d come previously was the age-gap comedyromance of Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter.

‘I was shooting Speed at the time I met Mr Arau,’ explained Keanu of his casting in the role. ‘I wanted to do some romance. I was attracted by the passion of the character. There is an honour about him. There is a nice connection between humanity and nature, with the wine and the family and the earth.’

Tackling this romantic character was something of a challenge for the actor. ‘The role was a tough test for Keanu,’ admitted Arau. ‘He was stressed and insecure about it. When I’d ask him to say a romantic phrase differently, I could sense he was worried he’d be criticised. I said, “Trust me, I’m watching over you. . .”’

Keanu recognised the problem within himself. ‘There are days when I’m OK,’ he said of his approach to acting. ‘Maybe it’s because I’m a Virgo; it’s in my sign to be hard on myself.’ Falling back on astrology to explain his difficulties with maintaining a credible performance during a whole film shoot, Keanu again plays up his airhead image. Rather than talk to journalists about the way he constantly strives to act better every time out, Keanu knows that a ‘New Age’, valley-speak explanation is what’s expected from him.

Much was riding on the back of this film for Alfonso Arau. Twentieth Century Fox had entrusted $20 million on Arau’s first English-language film on the basis of the success of Like Water for Chocolate. ‘It’s not my calling card to Hollywood,’ claimed Arau, ‘but to the world market.’ No matter how important it may have been, Arau used the stars as his guide. Scheduled to begin shooting on 28 June 1994, Arau moved everything forward a day as his astrologer suggested that the 27th would be a more propitious start date. He may have managed to shoot only one scene on the 27th, but it was enough in his own mind to have met the star-dictated deadline.

‘There is a dreamy quality to Walk’s set,’ said Robert Kamen. That was not only down to the cinematography, but was a product of the fuzzy mind-set that pervaded the key creative personnel on the film. Keanu Reeves was right at home.

That’s what some critics felt, too, about Keanu’s delve into straight romance. The change of pace from Speed was welcomed by most, and A Walk in the Clouds went some way to making up for the damage done by the poor performance by Johnny Mnemonic. It did good business at the box office and received broadly good reviews. One – the San Francisco Chronicle – felt that Keanu had shown himself to be ‘a mature, charismatic movie star’ and that there was ‘not just sweetness there, but depth’. Some critics, however, still had their knives out for Keanu personally, even if audiences seemed happy enough with his screen persona. People said: ‘Although Keanu is certainly handsome and hunky enough to play the romantic hero, his dogged earnestness and flat-as-a-spatula voice just don’t cut it. Combined, these two traits make [him] sound faux-Hemingway and dopey.’

For a change, the British press were more receptive to Keanu in this classic melodrama. Empire magazine simply noted: ‘Keanu looks very cute indeed’, while the Guardian thought he ‘pads handsomely through the film’.

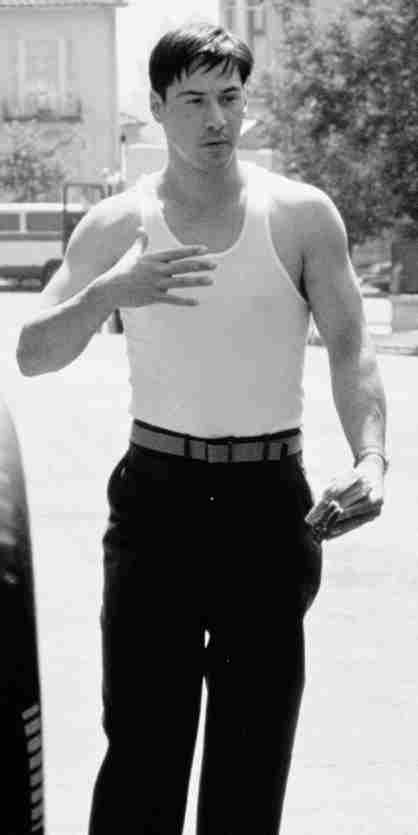

Keanu on the set of A Walk in the Clouds.

Keanu and Aitana Sanchez-Gijon at the premiere of A Walk in the Clouds.

After this, Keanu tried his hand at hosting a TV documentary recalling the horrors of the Nazi holocaust. As the host of Children, Remember the Holocaust Keanu introduced segments featuring the voices of Kirsten Dunst (Interview with the Vampire) and Casey Siemaszko (Breaking In). The programme, subtitled Through Their Eyes, was part of the award-winning CBS Schoolbreak series of educational documentaries for pre-teens and adolescents. The series explored conflicts facing today’s youth and the shows are developed with specialists in education, psychology, religion and related fields.

The one-hour documentary film depicted the Holocaust from the point of view of young people who lived and died under Nazi persecution (1933–1945). One and a half million children and teenagers were killed by Nazis, including Jews, Polish Catholics, Romanies (Gypsies), and the disabled. Children, Remember the Holocaust was based on chosen selections from young people’s diaries, letters, and survivors’ recollections, drawn together by writer D. Shone Kirkpatrick. Using archival film footage, still photography, sound effects, and period music, the film brought the past to life for today’s youngsters – who were further attracted to the project by the addition of Keanu Reeves as presenter. In the film the teenage actors speak the thoughts, feelings, dreams, and nightmares that those young people experienced.

Although not Jewish, Keanu had often felt strongly about injustices of all kinds and was happy to lend his name and presence to the project. His community drama school Leah Posluns had been attached to a Jewish community centre, although it was open to all denominations. Keanu’s empathy for the Jewish experience seems to have developed from his own sometimes itinerant childhood – and hosting a TV show was not something he’d ever done before. Always game for a new challenge, he threw himself into the project, even though it would prove to be no more than a minor footnote in his screen career.

Children, Remember the Holocaust was nominated in April 1996 in two categories for the 23rd Daytime Emmy Awards, the TV version of the Oscars. The network that screened the show, CBS, topped the list of nominations with a total of 69, including Outstanding Children’s Specials and Outstanding Writing in a Children’s Special for Keanu’s documentary. At the awards ceremony on 22 May, the show gained an award for writer D. Shone Kirkpatrick.

Keanu Reeves’s long-standing interest in the work of William Shakespeare had been clear throughout his career, most notably on stage in his 1985 Romeo and Juliet as Mercutio at Leah Posluns, and his Trinculo in The Tempest in 1989 at Shakespeare and Company in Mount Lennox, Massachusetts. It was Keanu who had sought out a role in Kenneth Branagh’s Much Ado About Nothing. At the time, Keanu had expressed his interest in playing Hamlet to Branagh – with the director encouraging the young actor to pursue it.

‘The first advice was to do it,’ recalled Branagh of his discussions with Keanu. ‘He had wondered if it would end up being a circus. He came to see me play Hamlet in the Royal Shakespeare Company and we had a long conversation. He was very gracious – the production was wonderful, it was great. And then we had a drink or two. He started to tell me what was wrong with it, and about three hours later I realised he hated the entire thing. “Well, you’ve got to do Hamlet, Keanu, because you obviously know how to do it – so off you go.” I love him. He’s a bright lad, much brighter than people think.’

Keanu’s chance came through an offer from Steven Schipper, who as Artistic Director of the Manitoba Theatre Centre had auditioned Keanu for a role in the Toronto Free Theatre when the actor was sixteen. Schipper offered Keanu a slot in his Winnipeg, Canada theatre for the standard Equity fee of just under $2000 per week to play any part he wished. Keanu teamed up with director Lewis Baumander, whom he had worked with on Romeo and Juliet, and together the pair decided to tackle Hamlet.

It was an audacious move for Keanu, who had suffered at the hands of the critics for many of his movie roles, particularly his period pieces and his Shakespeare turn in Much Ado About Nothing. However, Keanu was serious about tackling the part, and he threw himself into the role, opting out of a major part in a Tom Clancy film, entitled Without Remorse, which would have earned him $6 million. He also dropped out of playing the young lead role in Michael Mann’s Heat, alongside Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, only to be replaced by Val Kilmer, in a reversal of his Johnny Mnemonic experience.

Keanu had his first reunion with Baumander in February 1994, when he was in Toronto shooting Johnny Mnemonic. This initial discussion of the play, and the possibility of them staging it, was followed in May with a week in Winnipeg, examining the stage space available at the Manitoba Theatre Centre. After wrapping production on A Walk in the Clouds in October 1994, Keanu returned to Los Angeles, hooked up with Baumander, and threw himself heart and soul into preparing for his debut as Hamlet the following January.

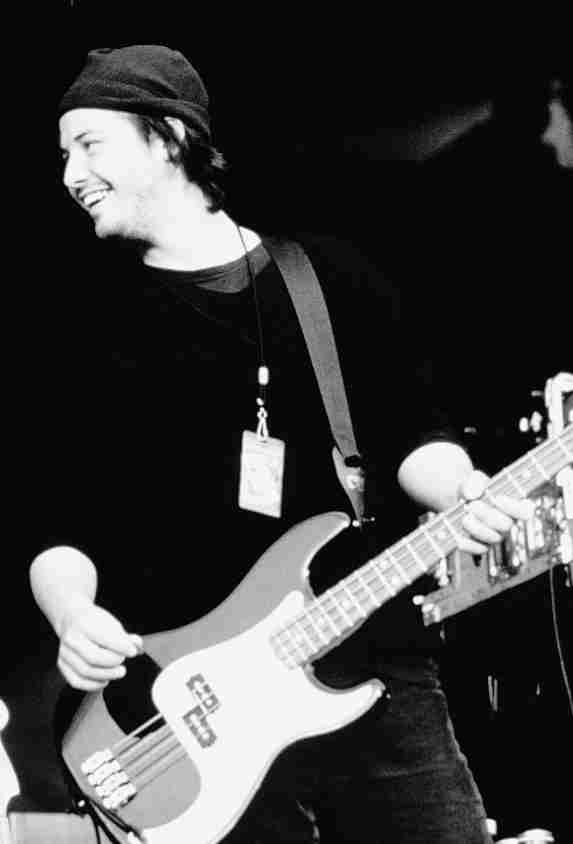

Keanu with his band Dogstar.

Keanu was clear in his reasons for tackling the role, and – more importantly – for doing it now, as he turned 31. ‘Hamlet is the absolute role, the role of which every actor dreams. Everybody told me, “But you can’t play Hamlet until you are 50!” That’s false! I would have loved to have played him when I was 18. It is the part of a young man for a young actor. It is complete – love, rage, confidence, doubt, treason, desire, spirituality. To me, none of the film versions of Hamlet have shown this.’

A month of full cast rehearsals took place in Winnipeg in December 1994, the first chance the rest of the cast of the production had to meet their leading man. Relief, reportedly, spread throughout the company when it became clear that Keanu was not doing Hamlet as some movie star ego trip. It was clear from his manner and dedication to the work that he was serious about playing Hamlet. Stephen Russell, a seventeen-year veteran of the Stratford Festival, played Claudius in the production and was impressed by Keanu’s preparation. ‘The thing that impressed me on that first day was how much work he’d done. This was not going to be a star turn or a walk in the park. And what I realised, too, was how his principles were etched in stone. He carries a lot of weight extremely well.’

Playing up Keanu’s physical strengths as an actor, director Baumander organised key scenes around him. There was no attempt, though, to simplify the language, meaning that the actor had to learn the entire play properly. Unlike in the process of movie-making, there could be no second takes if he was to dry up or fluff a line on stage – and he had 24 performances to get through in January and February 1995.

‘I love the play, I love acting Shakespeare, it’s the best part in Western drama,’ announced Keanu, arriving in Winnipeg only to be welcomed by a ‘Keanu hunt’ organised by the local newspaper. The international media was not far behind, arriving in droves to chronicle his latest attempt at the Bard. Wisely, Erwin Stoff turned down all offers to film Keanu’s stage performances, even denying Canadian national broadcaster CBC the chance to use clips for news reports. Clearly, Keanu’s handlers were worried that their client was out of his depth with this role and were attempting to minimise the damage that making a hash of Hamlet could cause.

As it happened, they need not have worried so much. The first night was packed out with representatives of the international press, many waiting happily to see Keanu Reeves fall flat on his face and make a fool of himself. It was not to be, but Keanu was petrified on the night. ‘One of the most horrific nights of my life, oh my gosh! I was surviving, not performing. But, it got better. It was a landmark experience for me, morally and physically. I left each night, exhausted and shattered,’ admitted Keanu. While his performances were variable, opinion seemed unanimous that Keanu’s Hamlet was at least not an embarrassment.

One problem Keanu had with playing the same part night after night was sticking to a consistent way of tackling it. Having little stage experience, Keanu was more used to performing for movie cameras, having several chances to interpret scenes and several takes to get it right. On stage with Hamlet, he could continue working like that if he really wished, but he had to do it live every night in front of an audience.

Some critics were predictably scathing, dubbing this Hamlet as ‘Keanu’s Excellent Adventure’, of course. Several key critics, however, were astonished at how good Keanu actually was. In particular, Roger Lewis of the Sunday Times was immensely impressed: ‘He is one of the top three Hamlets I have seen for the simple reason that he is Hamlet. . .full of undercurrents and overtones. He quite embodied the innocence, the splendid fury, the animal grace of the leaps and bounds, the emotional violence, that form the Prince of Denmark.’

‘That was kind of him,’ commented Keanu of this extremely positive notice. ‘What was great was that he had seen more than one performance. It wasn’t just opening night . . . I met a number of people who had never seen a play before, who said it’s one of the most special events that’s happened in their life, and that’s right on, you know. I’ll say one thing about our production – and I don’t care what you think about my Hamlet – you could hear it, it made sense, it wasn’t abstract, it wasn’t convoluted or sensationalistic. Everyone had their place in the play and it all made sense.’

Keanu continued: ‘I read Hamlet in high school and then I remember being shown Lawrence Olivier’s Hamlet, but I guess the first thing that drew me was the angst – just being a teenager and having to read “To be or not to be.” That was the hook that has drawn me into the path of Hamlet. I haven’t played Romeo, or any of the larger parts in Shakespeare. I’ve played Mercutio and I’ve played Trinculo from The Tempest, and I did a kind of abridged Don John, so to play the second largest part in Shakespeare is a bit daunting.’

Reaction to Keanu Reeves playing Hamlet was extraordinary. The entire run of the play sold out and hotel rooms throughout Winnipeg were booked up as fans from around the world descended on the unsuspecting city. One female fan flew all the way from Australia and stayed throughout eight nightly performances.

Keanu did not ignore his fans, who queued up at the stage door afterwards in temperatures of sometimes minus 20 degrees, hoping to catch a glimpse of their movie idol. Keanu gave them more than a glimpse, often spending several hours signing autographs and chatting with fans, claiming he’d feel guilty if he didn’t.

Security became an issue for the star, as his minders became worried about the fanatical nature of some of the people who were turning up outside the stage door night after night. Keanu, though, enjoyed the attention. ‘So long as they don’t have any knives, guns, poisons or voodoo . . . it’s flattering and hopefully people like what I do. It was astonishing that some people had travelled so far. It really intensified for me that I had to put on a good show. It was great for the other actors, we had the best audiences ever. People were standing up and clapping and everyone enjoyed the piece.’

A trio of female Keanu fans from Chicago recounted their experiences on a special Hamlet Internet site they set up, in tribute to their screen idol. ‘The Canadian immigration officer simply asked, “Are you here for the play?”’ wrote one of the three. ‘I nodded and he promptly wrote Hamlet on my entrance visa! We caught the closing performance, and to put it bluntly, the performance was much better than we expected! We were rewarded for our fortitude in braving the subsub-sub-zero temperatures with confident and capable performances that were captivating. . .we all came back with autographs, big film-developing bills, many new friends from all over the world, and a new appreciation for long underwear.’

On tour: Keanu takes his ‘hobby’ seriously.

It seemed that no matter what Keanu Reeves got up to, his loyal fans would always go the extra mile to support him in his endeavours.

Keanu Reeves had been able to indulge one of his other off-screen interests during the production of Johnny Mnemonic – rock music. The casting of Ice T and ex-Black Flag member Henry Rollins brought Keanu into contact with one of his rock idols. ‘I know Henry Rollins through a couple of Black Flag albums,’ said Keanu. ‘He’s such a cool cat, man. He’s got some good scenes in this. We were filming in a place in Toronto, an old opera house and Henry was like, “Yeah, when we played here we tore this place up!” He’s a very remarkable person.’

Keanu had taken his interest in rock ’n’ roll music to the next logical stage, playing in his own band. He’d acted out the rock star role in Paula Abdul’s ‘Rush Rush’ video. The screen star, however, decided to take a back seat in his band’s musical endeavours. He plays bass in Dogstar, but is not the front man and certainly doesn’t sing very often. And Dogstar did not join the thrash metal Johnny Mnemonic soundtrack. ‘Dogstar didn’t make it onto the soundtrack,’ laughed Keanu. ‘They left it up to the professionals.’

Although Keanu was inclined to downplay his musical ambition, what he usually termed a hobby began to take a more central role in his life – to such an extent that the actor would later forgo lucrative movie roles to go touring the world playing in Dogstar. ‘Because I’m an actor and I’m playing music, I prefer the term “hobby” more,’ said Keanu. ‘I know musicians have career ambitions, but the ambition is to have your music heard. I have a good time. Sometimes my friends come out and sometimes they don’t. Sometimes I tell them not to come. But it’s good fun.’

The band had begun in 1991 when Keanu had met Robert Mailhouse, an actor in the daytime soap Days of our Lives, in a supermarket. Mailhouse had also featured in a guest spot on Seinfeld as Elaine’s gay boyfriend and several Aaron Spelling productions, including Models Inc. Keanu – ever the hockey fan – noticed Mailhouse was wearing a Detroit Redwings hockey sweater. Hooking up through hockey, the pair of new friends soon moved onto a shared interest in music, engaging in private jamming sessions. Soon Mailhouse had recruited another friend, Gregg Miller, and Dogstar was born. Mailhouse even gained extra acting work through his connection with Keanu – he’s one of the executives trapped in the lift in the opening sequence of Speed.

It’s only rock’n’roll: Keanu’s other career as a member of grunge rock band Dogstar.

‘We started playing together,’ recalled Keanu, claiming that the supermarkethockey jumper story was true and not merely band-invented PR. ‘He would do drums and keyboards and I would play bass.’ Joined by Gregg Miller – also an actor who featured in Who Shot Pat? opposite Keanu’s Speed co-star Sandra Bullock – the band practised on cover versions of Joy Division songs and others by the Grateful Dead.

Spurred on by their good vibes, the group decided to play live. ‘Which was a huge mistake,’ said Keanu. ‘We were called Small Faecal Matter back then,’ recalled Mailhouse. ‘I’m surprised, actually, that for such clever lads we couldn’t come up with a name,’ admitted Keanu. ‘We were BFS too – I called us Bull Fucking Shit or Big Fucking Sound . . .’ As BFS the band played at the Roxbury, when it was considered to be LA’s hot night-spot, the same night Madonna was holding a birthday party. It seems unlikely the material girl could be distracted from her revels long enough to pay much attention to the band. ‘I think she was playing spin the bottle with strippers,’ claimed Mailhouse. ‘There we were in this tiny bar at the back and she was having this party where everyone was probably spanking each other.’

The band continued perfecting their act, joined by fourth member Bret Domrose, the most seriously musically-minded of the quartet. Soon, they’d settled on the name Dogstar, another name for Sirius, the brightest star in the sky, and became the resident band at Los Angeles’ club the Troubadour. With Keanu Reeves playing in the band, their shows hardly needed to be advertised and always sold out. Dogstar would play to a venue packed with screaming teenage girls and older women with their boyfriends in tow.

People magazine was soon reporting on the phenomenon. Writer Lorraine Goods noted that Keanu was too busy concentrating on his bass playing to perform to the crowd, although the crowd seemed there to perform themselves. One unnamed 24-year-old man noted: ‘It was actually better than I expected. I went because my girlfriend is in love with Keanu Reeves. It was mostly women. . .’

As the notoriety of Dogstar grew, so the Troubadour became too small to hold the screaming, bra-throwing crowds. During performances, each of the four members of the band would take turns on vocals, including at least one song from Keanu. Their original songs boasted titles like ‘Ride’, ‘Camp’ and ‘Cardigan’. Keanu even tried his hand at writing songs, including ‘Isabelle’, about a friend’s three-yearold daughter, and ‘Round C’. ‘That’s the name of a Cheddar,’ he explained to The Face writer Lesley O’Toole. ‘But it’s really about love.’

The experience of singing on stage was a different one for Keanu, who was not used to performing in public, even after his turn as Hamlet, just in front of movie technicians. ‘I’m new to this,’ he freely admitted. ‘When I sang ‘Isabelle’, it was the first time this has really resembled the best part of acting. When you can feel it, your blood thrills, it’s physical, your heart is open. It’s emotional and sharing. . .’

By February 1995, Dogstar were venturing further afield as their following grew larger. They played at Belly Up in San Diego, before returning to Los Angeles, forgoing the Troubadour in favour of the much larger and more trendy American Legion Hall. During this period a couple of album offers were turned down by the band, worried that they might simply cash in on the novelty aspect of Keanu’s participation.

In June 1995, Keanu and the others had flown off to Japan to play a six-date tour, Japan being a country where Keanu had a large and dedicated fan following. He’d featured in a commercial for Suntory Whisky to be shown exclusively in Japan. Upon returning, a six-week US tour was planned, but Mailhouse found the planned dates clashed with the shooting of a TV pilot entitled Road Warriors, based on the Mad Max movies, in which he had a featured role. When the series was not picked up, Dogstar were back in action once more. Keanu had set aside two months for Dogstar between the shooting of his next film, Feeling Minnesota in mid-June, and his scheduled start on Chain Reaction in September 1995. The Dog Days of Summer tour took in twenty US cities, ending on 18 August at the House of Blues in Los Angeles. A documentary film crew followed the band, in true This is Spinal Tap fashion, chronicling their backstage antics and cataloguing the attempts by Keanu’s fans to get backstage and meet the actor-cum-rock-star. The director of the piece was rock video helmer and Keanu buddy Joe Charbonic.

On 29 September, the band had opened for Bon Jovi at the Forum in Los Angeles, as well as for David Bowie at the Hollywood Palladium. Then it was a trip down under for a mini-tour supporting Bon Jovi again, beginning in Auckland, New Zealand at the Supertop on 8 November, finishing off on 18th November at the Eastern Creek, in Sydney, Australia. By then the band had signed the now inevitable recording contract, with Zoo Entertainment and the BMG label. Soon there was a Dogstar fan club and official tour merchandising.

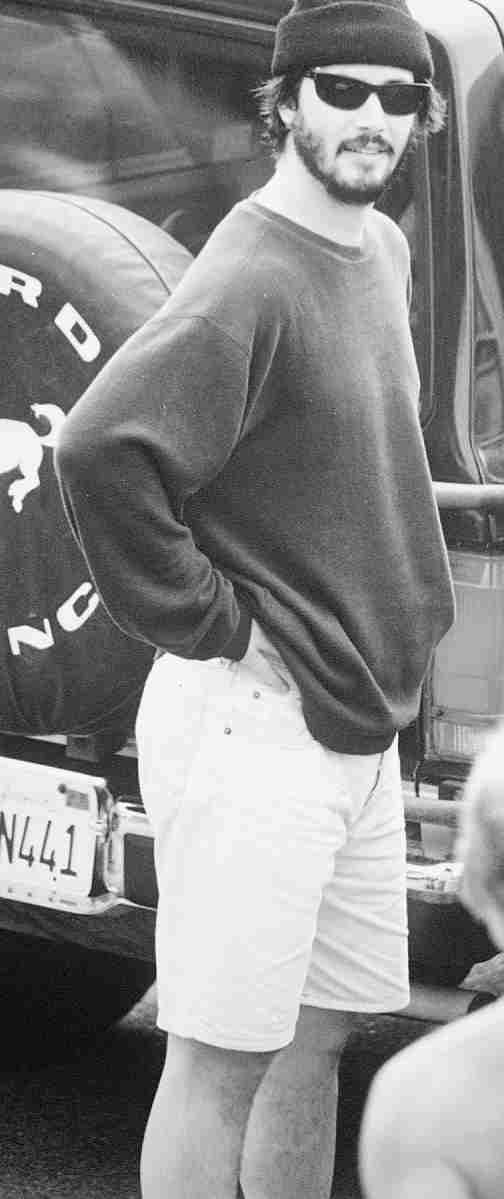

Writing in the Sydney Morning Herald, Katherine Tulich reviewed the performance, calling Keanu’s playing ‘inconsistent’ and noting he left the spotlight to Bret Domrose and Robert Mailhouse, Miller having by then quit the band to pursue acting opportunities: ‘Keanu shuffled coyly on the side of the stage, didn’t sing, barely talked, hid most of his face under a black beanie and had his eyes on his scruffy black Doc Martens through most of Dogstar’s 30-minute set of thrash grunge.’

‘I admit it’s pretty nerve-racking for me to go on stage,’ said Keanu, ‘but I’m getting more confident the more we play. I know people are coming to see me because of my cinema work, but if that brings an audience in to hear the music and gives the band a shot, then I’m grateful. We’ve been working really hard, practising for hours every day, so I think we’re pretty good now.’

Just as momentum was beginning to build behind Dogstar and Keanu Reeves began musing aloud about seriously pursuing his musical interests by going on a world tour during the summer of 1996, Hollywood intervened, offering the actor a $10 million salary to appear alongside Sandra Bullock in Speed 2. Shocking many, including his own advisers, Keanu said a firm ‘no’, offering his desire to tour with Dogstar as the official reason for declining. Speculation mounted that there were other reasons. Since Speed, Keanu had been piling on the pounds, as was to be horribly evident in his next film Chain Reaction, and the actor couldn’t face the prospect of re-entering the gym to tackle his weight problem and get back into shape. Gossip columnist Liz Smith even reported that Keanu was simply ‘over’ being a mega-star and was not interested in taking on a role which could cement his status as an action hero.

That left 20th Century Fox with something of a problem. Most franchise films featured the return of the same characters played by the same actors. In those where changes had been made, the characters were usually well known by the public through different sources – for example Batman in comics and on TV, or James Bond in books and movies. It was different for Speed, as one 20th Century Fox executive admitted to the Los Angeles Times. ‘The characters in Speed were originated by these two actors, so audiences expect to see them again.’ Having failed to secure the return of Keanu, however, the studio were not going to let a good franchise go to waste and set about replacing him with Jason Patric after considering A Time to Kill rising star Matthew McConaughey and B-movie man Billy Zane. The plot is to feature Sandra Bullock taking a trip on a cruise ship, only to have it hijacked by terrorists.

Many thought Keanu had fumbled the ball by refusing to tackle Speed 2 and deciding to concentrate on his work with Dogstar instead, but the conventional views of Hollywood wisdom seemed to have less sway over the actor once he’d passed the age of 30.

It was during 1996 that his band were to have their biggest impact – exactly at the time that Keanu would have been shooting Speed 2 if he’d signed on for the sequel. That summer Dogstar debuted in Europe, notably playing at Glasgow’s T in the Park music festival in mid-July and a gig at London’s Shepherd’s Bush Empire on 16 July. Reviewing the open-air gig at Strathclyde Country Park, Pat Kane (of Scottish pop group Hue and Cry), wrote in the Guardian: ‘When Keanu finally stumbles on stage, the screams are a symphony of the ages of woman. “Kee-ahh-noooh!” Personally, on the bodacious front, I felt short-changed. For one thing, there’s some unnecessary democracy going on in Dogstar . . . [with] Keanu flailing away at his axe in semidarkness. When he wriggles his shoulders (once), blows kisses (twice) and does his slomo grin (thrice), you see what a preposterously successful rock-god Keanu could be. . .’

British women’s fashion magazine Elle sent reporter Kate Spicer to track Keanu down on his travels across Britain, beginning with his stay at Glasgow’s Forte Post House hotel, where the manager commented that in person Keanu was ‘just a normal guy, a nice polite man. I don’t know why he always acts like a space cadet in interviews.’ Spicer was not the only one on Keanu’s trail, as the fan posse were also after the star, just as they’d turned up for Hamlet in Winnipeg. The tour bus located at T in the Park ended up being covered in pink lipstick messages including: ‘Do Speed 2 or else’ and ‘We love U Keanu’. The story was the same when the Dogstar crew arrived in London. Fans were soon ensconced outside the Blake Hotel, hoping to catch a glimpse of Keanu. The Daily Record reported that Keanu had dined at a local Indian restaurant and – in a seeming dig at his more portly state – felt obliged to report that he also snatched food from his friend’s plate too.

Keanu seemed determined to play down his superstar status during the tour and play up his ‘ordinary bloke’ persona. He refused to do any significant press interviews while touring, and certainly didn’t want to talk about Hollywood, films, or whether he’d be doing Speed 2 or not.

Dan Thomsen, Dogstar’s PR manager for the tour, emphasised that Keanu wanted to separate his movie star and rock band images. ‘People keep trying to equate Keanu Reeves the movie star with the band. Nothing is going to be as big as a movie star. We’ve been getting really annoyed with promoters who put Keanu Reeves on the billboards.’

While Keanu had taken his interest in playing rock ’n’ roll far more seriously than Johnny Depp (who sticks to playing in his own club, the Viper Room) or Brad Pitt (who sticks to playing alone in private), the best advice anyone could offer was not to give up the day job.

There was no turning back for Keanu Reeves. He was now an A-list star in Hollywood, but it wasn’t a tag he was too comfortable with. ‘What is a star? A megastar? It’s a word to describe people who have gleaned large success in entertainment. I don’t wanna be so popular as to be recognised wherever I go. If it’s something I can get around doing and still act in popular films, then I will. I’d like to hopefully do some radical, experimental, independent films.’

Throwing off the action hero mantle was top of Keanu’s agenda, and he quickly lined up some low budget independent roles in Feeling Minnesota and The Last Time I Committed Suicide, but he also knew to keep his blockbuster credentials by signing up to Andrew Davis’s action thriller Chain Reaction.

His restlessness, both personal and professional, does much to define Keanu Reeves. His unsettled nature and his wide variety of roles and films prevents him from being pigeon-holed as an actor or as a person. ‘I’ve settled on not settling,’ he boasted. ‘I’m still exploring, but I’m also trying to be clear about what I can and can’t do. I’m just not as developed as some other actors at my age. I’m not a producer or a director. All my energy is focused on acting. I’m limited and I’m still working to find a way inside my characters. But once you’re inside, I’m learning, limitations seem to vanish.’

Grunge guru: He may be a millionaire megastar, but Keanu likes to dress down on tour with Dogstar.