Style is the perfection of a point of view.

There’s no denying that French country has dressed itself up since Louis XIII ascended the throne in 1610. Where rough-hewn furnishings tinged with the nostalgie of the early seventeenth century once held sway, these days grace and glamour reflect in settings with a bit more flair, attesting to the way we live and entertain. Which is to say that the appearance of French country, echoing the furniture, fabrics, and accessories linked with the région of Provence, has changed over the years.

Of course, there will always be aficionados dutifully faithful to the style of Louis XIII set in a world far simpler. But on this side of the Atlantic, it seems most Americans have forsaken such Provençal clichés as hand-made rag rugs, dried bouquets, farm animals, and pillows with homespun sayings in favor of less subtle elegance.

While France has cut its work week to thirty-five hours, changed its presidential term from seven to five years, given women parity on ballots, let citizens from other European Union countries vote and run for office, and even created a type of marriage that can be dissolved on three months’ notice, Americans have boldly shored up defenses in a war against terrorism, attacked domestic issues, and knowingly or not, unceremoniously fashioned an image of French country that is distinct from the French. For a while now, in fact, French country has been a widely accepted catchall term for furnishings alluring and enduring, in step with the twenty-first century here in the States.

Admittedly, blending stylistic elements from different countries produces settings that sometime outdazzle those of our oldest allies, raising some eyebrows in France, where critics contend we take a more showy approach to country décor. What passes for French country in the United States, they say tactfully, bears only a fleeting similarity to le style Provençal, grounded in simplicity. In truth, it is safe to assume that stateside rooms boast fabrics and furnishings the people of Provence would scarcely think of using.

Fulfilling visions in costly high-rises with luxurious square footage, two-story villas with mansard roofs and dormer windows, as well as houses more upscale than their modest looks imply is a redefined treasury of refined furnishings laced with ties to Italy and the Far East, but drawn mostly from a blur of styles descending from France’s kings.

It is inarguable that four French monarchs—with ascending Roman numerals affixed to the name Louis—shaped the taste of their day with expertly crafted commodes culled from the finest ébénistes (cabinetmakers who specialized in marqueterie ) and chairs, consoles, and coiffeuses (dressing tables) built by highly skilled menuisiers (joiners who made furniture out of solid wood). Common characteristics set apart the pieces from earlier to later eras. This is not to imply that any one desk or armoire necessarily displayed all traits, or that any one site was its final resting place. Tellingly, in fact, the French and Italian words for furniture— mobilier and mobilia —literally mean movable. Bolstered by large staffs, a number of royal residences at their disposal, and thoughts of their own comfort, French monarchs moved restlessly with the seasons from one sumptuous dwelling to another, crossing the River Seine with an inventory of imperial trappings that ranged from staggering to modest.

Once a series of civil wars known as the Wars of Religion or the Huguenot Wars (1562–98) were victoriously put behind him, Henry IV (1553–1610) looked to foster France’s independence by reducing the need for costly imports and encouraging talented artisans from Italy and the Low Countries to set up workshops in the cavernous Grand Galerie of the Louvre, which had been transformed during the reign of Francis I from a fortress into a Renaissance palace. Loosening restrictions, the king granted permission for a brigade of leading metalsmiths, clockmakers, engravers, weavers, and others to work for private patrons as well as the court, and authorized them to train apprentices, too.

Since Louis XIII was only nine years old when his father, Henry IV, was assassinated in 1610, his mother, queen Marie de Médici, was appointed régent, or temporary governor of France. With obsessive ties to Italy and without any constraints, she boldly reversed policies set by her late husband, then ominously depleted a carefully amassed treasury with her astounding extravagance, including the purchase of exuberant Italian Renaissance art.

Furniture design, however, showed more restraint. Craftsmen built primitive, somewhat plain, armoires studded with somber geometric carvings, primarily diamonds and discs. Most were fabricated from oak or walnut, though many of the more soulful armoires were sculpted in supple pine.

Massive boxy chairs had bun feet and spiral or bead turned legs with stretchers joining the legs in an X or figure eight. Elaborately embossed Cordovan leather, velvet, damask, and tapestry needlework covered seats that were frequently glossed with fringe.

No different than in the time of ancient Egyptians, beds were the ultimate symbols of wealth; however, they fell into the domain of the upholsterer rather than the furniture maker, since frames were rarely carved. Bed hangings hid simple bedposts, offered privacy, and protected against cross drafts. Mattresses were stuffed with straw, leaves, and pine needles. There were no box springs; instead, a wooden frame supported a platform of planks.

To escape the stuffy, stifling formality framing life at the Louvre and a litany of ceremonial duties, Louis XIII and his wife, Anne of Austria, fled the French capital in 1624. In the serene forests of Versailles, fourteen miles southwest of Paris, the king built a modest retreat where he could indulge in hunting, his favorite sport.

But his son Louis XIV had grander visions for Versailles when he became king in 1661 at age twenty-three. Impulsively, he turned the hunting lodge built by his father into the most awe-inspiring château in Europe; next he turned his attention outdoors. With help from André Le Nôtre, the most acclaimed French gardener, land less than perfectly suited to plantings was leveled, drained, and shaped into a lavish horticultural fashion show, opulently garbed in 460 fountains that are still working today, trees imported from around the world, formal avenues of elaborate length, ornamental canals, stone statuary, and landscaped gardens more beautiful than those in Italy.

In pursuit of the most regal palace on earth, the Sun King and his chief architect, Louis Le Vau, created a series of lofty, almost ceremonial spaces designed especially for sleeping, eating, and socializing. Chambres (bedrooms), antichambres (salons), garde-robes (dressing rooms), and cabinets (studies) layered in overwhelming splendor fueled a taste for grandeur at every turn.

Along the way, motifs were pieced together from architecture, flora, fauna, and the instruments of war. The same attention-grabbing fabric bedecked curtains and upholstery while clinging insistently to padded walls, which, in fact, helped filter the damp, misty cold that often settled over the town. Yet for all the apparent affluence at the palace, only Louis XIV had the use of a proper bathroom with running water.

In keeping with royal demands, the king’s maître ébéniste (chief cabinetmaker), André-Charles Boulle (1642–1732), laboriously fashioned the finest woods into regal inlaid furniture, baroque in its elaborateness. As if also exhibiting proof of the court’s unassailable wealth and authority, intricate tortoiseshell, brass, ivory, and mother-of-pearl were veneered into marqueterie patterns, exaggerating the beauty of each piece. Rich ormolu, or gilded bronze moldings and medallions, further defined elegance, enticing royals, nobles, and aristocrats eager to maintain their place in society to emulate the king’s extravagances even when the largess was beyond their reach.

One literally needed a title, however, to experience the majesty of the tall, ostentatious chairs with upholstered, haughty-looking backs and stretchers reinforcing the legs. Since only the self-indulgent king and his wife were allowed to sit in a fauteuil, or armchair, there were an abundance of tabourets, or lowly stools and benches—all robed in regal fabrics, including tapestry and embroidered silk.

Shimmering brocades lavishly threaded with gold, exquisite damasks, and splendid velvets garnished with handmade silk passementerie —fringes and tassels—took one’s breath away. Famed Gobelin tapestries made in Paris and carpets on neutral grounds from Aubusson, Beauvais, and the merged Savonnerie and Gobelin factories presented a tantalizing glimpse of seventeenth-century decorative arts.

With all of Europe watching, ceilings and walls ablaze with frescoes —paintings on wet plaster with origins in fourteenth-century Italy—shamelessly begged to be noticed. Elaborately carved boiserie, gilded or spiced with gold leaf, replaced solid wood trim. And the dazzling Hall of Mirrors, whose glass was made at Saint-Gobain and then silvered in Paris, gave a publicity boost to the king’s insatiable appetite for excess. As a result, baroque furnishings became known on the Continent as Louis XIV, and the influence of the French replaced that of the Italians and Spanish. Over time, people on both sides of the Atlantic would name French furniture, in the design of the period, for the reigning king.

When Louis XIV died in 1715, his five-year-old great-grandson, whose parents and brother had passed away earlier, assumed the throne as Louis XV (1710–74) under the regency of his cousin (twice removed), Philippe II, the Duke of Orléans. When Philippe died in 1723, Cardinal de Fleury advised the young king from 1726 until 1743, at which time Louis XV governed alone until his own death in 1774.

The transitional period between the opulent baroque and the less formal rococo era of Louis XV became known as French Régence, or Regency. It should not be confused with the Regency era in England from 1811 to 1820, when the future George IV was named regent and furniture resembled the French Directoire period (1789–1804), with its Revolutionary motifs or the French Empire style of Napoléon and Josephine that followed (1800 to about 1850).

Offended by the unrestrained ancien régime, the endless ritualistic pageantry of Versailles, and even having the world at his feet, the régent moved the royal court to Paris, where courtiers lived in hôtels particuliers, or private residences, suited to a less pompous way of life without great fanfare. Perhaps inevitably, intimate petit salons ushered in an era of less cumbersome furniture with sweeping curves while rejecting the heavily carved baroque pieces of Louis XIV.

Shapely cabriole legs replaced straight ones on chairs, clocks, and case pieces— armoires, bookcases, and writing desks all designed as storage. With motifs inspired by the foliage of the region, delicate bouquets wrapped with ribbons and bows graced the upper sections of armoires.

Rather than resting on their laurels, master cabinetmakers fashioned a low chest of drawers called a commode, which differed from the bureau commode, or large table with drawers that was crafted in the baroque period. Then, the bombé commode, with a puffed chest and plump sides, made a grand entrance. Startlingly beautiful wall paneling with softly curved corners also draped the French Régence era.

Furthermore, a fascination with the Far East, which had begun in 1670 when the Trianon de Porcelaine at Versailles was built for one of Louis XIV’s mistresses, increased. When demand for all things Oriental—from silk screens and lacquered cabinets with gleaming varnished finishes to blue-and-white porcelain vases and embroidered hangings—outstripped supply, French craftsmen copied these richly decorated pieces, then added showy flourishes of their own to the ones that inspired them. The look brought together Far Eastern inspiration and Western craftsmanship, creating the foundation for the style known as chinoiserie, which is still fashionable today.

The Régence era pointed the way for the more beguiling rococo period (1730–60), when Louis XV and his official mistress (maîtresse en titre) Jeanne-Antoinette Poisson, or Madame de Pompadour, had great influence on the decorative arts. Though public reception rooms retained their sense of glamour and grandeur, family apartments were refashioned into less formal settings where strong colors were replaced with the pastels favored by Madame de Pompadour. With a new reserve embracing comfort, Louis XV sought inviting chairs, rather than stools, and fluid furniture arrangements conducive to talk.

As a result, the king’s highly skilled menuisier, Jean-Baptiste Tilliard, sculpted a perfectly proportioned low, curved armchair with an exposed wood frame, far lighter and less regal-looking than any former chairs. On the seat rail of the bergère, he carved a basket of flowers. On its back, he shaped shells and cartouches, or fanciful scrolls, which communicated that this chair was not meant to stiffly line the wall but rather to be moved about for impromptu use.

As Parisian chairmakers began adopting Tilliard’s designs, the frames of both caned and Louis XV bergére chairs were at times gilded or painted. Upholstered arms were moved back from the length of the seat so that au courant crinolines would not be crushed. When hooped skirts were no longer in vogue, they would again extend forward, but the soft, loose pillows still rested on fabric-covered platforms and curvaceous legs remained stretcher-free. Even centuries later, the rich damasks and velvets favored for upholstery would be seen as the height of chic.

Meanwhile, the chaise longue (in America spelled chaise lounge ) emerged as a tour de force that Americans would come to embrace, followed by the escritoire —also called a secretary—a small desk with drawers and cubicles.

Painstaking carvings on wood pieces, some magnificent beyond description, were pulled from all aspects of nature, including shells, fish, waves, birds, vines, flowers, rocks, and serpents. Also, designs were commonly rooted in farming motifs such as corn and wheat. Ribbons with streamers and hearts became popular, too.

By the second quarter of the eighteenth century, dwellings in Paris flashed brilliant crystal chandeliers and small, exquisitely carved marble mantels with large mirror panels, or painted overmantels called trumeaux. Wood floors were arranged in marqueterie patterns or in large Versailles-like parquet designs, and then warmed with alluring Aubusson or Savonnerie rugs.

Whereas the baroque style of Louis XIV exuded a passion for symmetry, firmly holding that any chair, room, or château divided vertically should be a precise mirrored-image half, the rococo style of Louis XV once again endorsed asymmetry, born in the Régence era.

Not everyone in France, however, was sold on grandeur, let alone gloss. Many people preferred the unpretentious beauty of pieces produced outside Paris that were redolent of woods in surrounding regions. If not quite astounding, armoires and commodes were sufficiently commanding—generously scaled, graceful, and easily identified by intricately carved decorative panels studded with exacting motifs. Eagles, flower baskets, and garden instruments, for instance, were the favored ornamentation in Lyon, Arles, and Nimes respectively, where furniture was sturdily crafted in walnut.

Others opted for the unassuming splendor of neoclassical style, replete with refined straight lines and striking proportions sans fussiness. In a conscientious retreat from obvious excess, Parisian ébénistes adopted motifs from ancient Greece and Italy’s excavations of Herculaneum (1738) and nearby Pompeii (1748), adeptly creating furniture with more subtle details suiting Madame de Pompadour and her brother, the Marquis de Marigny, who were first struck by the fresh beauty of neoclassicism before the death of Louis XV.

During Louis XVI’s reign (1774–92), he and his queen, Marie Antoinette, further defined neoclassical style with astonishing sureness. Although oak was valued for its hardness, the royal couple coveted case pieces crafted in mahogany, helping the wood to flourish in their distinctive decorative image. Also thanks to their unmistakable influence, ebony, which had fallen from favor after Louis XIV sat on the throne, returned to undisputed glory as demand mushroomed.

Partial to purple, the queen splashed private rooms in her favorite shades, washed wood pieces in dignified greenish-gray, and enveloped her Versailles boudoir with a toile de Jouy, while her husband decreed that the Oberkampf factory in the French town of Jouy-en-Josas, not far from the palace, be elevated to royal-supplier status.

In the place of extravagantly carved wall paneling, smartly understated boiserie modestly adorned with acanthus leaves and small rosettes ascended walls. No longer were ceilings covered with frescoes; instead, they remained plain, while doors, windows, and marble mantels outlined in thin moldings looked pleasingly elegant amid growing social unrest.

Differences aside, four French kings revolutionized decorating by crafting styles that would forever remain the personification of good taste. But by no means are the French alone in their appreciation. Transcending time zones and connecting cultures, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century furniture from Louis XIII to Louis XVI is highly sought the world over.

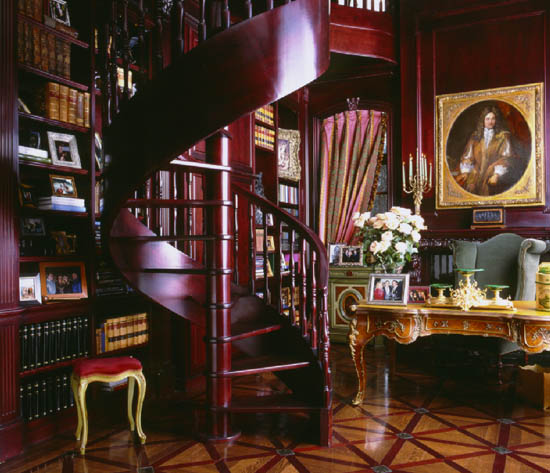

Hidden lighting meanders like the Yangtze River over a collection of ancient leatherbound books in a two-story library, glazed Chinese red. As the dramatic spiral staircase rises to the gallery, Louis XIV reigns over a magnificent Louis XV bureau-plat, circa 1820, with a hand-tooled leather top and exuberant figural-bronze mounts. Equally impressive are flowers inlaid into the cross hatching.

Praiseworthy wines flow in a candlelit tasting room intended for entertaining. Framing the space—built into the hollow of a rock—are embossed leather chairs still enjoying a life of privilege, plus an antique Empire table dressed in cut velvet.

Swathing a Stateside dining room in glamour are boiseries, or exquisitely carved panels that once adorned a magnificent French château. Skillfully painted oils on canvas—original to the sections—give rise to gracious living as guests and the home’s owners alike savor their old-world splendor.

Storyboards depicting various stages of winemaking adorn the front panels of a twentieth-century tap room bar. On the back bar is a cut-to-clear carved glass mirror of the Eiffel Tower, Paris’s best-known monument, built for the Exposition Universelle of 1899.

An important William IV four-fold, double-sided screen, bought at auction, lends drama and interest to a New Orleans dining room. Each panel is adorned with four paintings—some French scenes, some not—all by artist James Digman Wingfield, a member of the Royal Academy.

An eighteenth-century blackamoor —a decorative statue usually gaudily clad in oriental wear—keeps watch over a dining room.The sophisticated silk curtain fringe is custom from Smith & Brighty, London.

Dressmaker details are a hallmark of New Orleans designer Gerrie Bremermann’s far-from-basic window treatments. Here, intricate folds are worked into the curtain heading, while braid—flat trim first woven on the jacquard loom of the Napoléon era—creates a decisive edge. According to the late Sister Parish (1910–94), one of the most influential tastemakers of the twentieth century, “Curtains must always have an edge or an ending,” a dictum adhered to here.

Holding most everything a breakfast room needs, a cupboard dating from the eighteenth century is clad in its original paint. Set against color-washed walls, it is topped with Chinese export china.

What was once a stable on a large New Orleans estate is today an inviting home. Reflecting a lifetime of avid collecting are a Napoléonic bench and an eighteenth-century trumeau —an overmantel with a mirror and painting. Exquisite miniature portraits painted on ivory, tortoiseshell, and silver date from the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

To suggest the look of a chic salon, fine French furniture is juxtaposed with equally impressive antiques. Black lacquered Régence chairs, swathed in an Old World Weavers’ tiger stripe, flank the lit de repros, a daybed covered in a Scalamandré stripe. Napoléon was especially fond of stripes and used them lavishly in decorating both his state and private homes.

A collection of nineteenth-century botanicals—purchased in one fell swoop—decorates an entrance-hall stairwell. Although no two frames are exactly alike, their similarities unite the space. The grouping is from The Gray Door, in Houston.

An entrance hall is not simply for welcoming guests or rushing through on the way to more important areas. Although not necessarily a room, it has the power to insure that important first impressions are positive and lasting. Stepping out of France is an exquisite mirror that hangs above a nineteenth-century console. With all things Italian also in fashion these days, faux-painted walls host eighteenth-century paintings—perhaps left by generations past.

For centuries, the bedroom was where high-level meetings took place, until Louis XV’s renowned mistress, Madame de Pompadour—the arbiter of eighteenth-century taste—removed it from the list of public rooms. After that, it became worthy of being called a boudoir , which in French means a lady’s private retreat.

Fresh flowers are among the special touches that help create an intimate mood. The arrangement on the bedside table is by Jeffrey Lee and Rajan Patel, the creative forces behind Urban Flower in Stanley Korshak’s chic Dallas floral shop.

Voluminous silk taffeta, in one of Travers’ iciest hues, is edged in a Houlès blue, marrying lightness and grandeur on a French rug dating from the 1920s. All are free of worries about patrimoine —the French law that strictly forbids unique or historically important works of art from leaving the country. Actually, in the last decades a number of countries, including Italy and Egypt, have banned the export of certain treasures.

On this side of the Atlantic, vintage crystal jars and perfume bottles elevate the daily ritual of putting on cosmetics. Hundreds of years ago, Madame de Pompadour ceremoniously encouraged courtiers to present themselves at an hour when she would be à la toilette, aware that she looked especially alluring at that time.

A powder room tampers with perception by exuding passion for trompe l’oeil , a decorative technique rooted in ancient Rome. The term, however, is French. The sink—unearthed at the Marché aux Puces, the famed Paris flea market—was given a new life with fittings from Herbeau France; they are also available at Herbeau Creations of America, Naples, Florida.

French style is reflected in a table set with considerable panache.

A detail of a centerpiece that rivals anything created in France.

Above and Below: The beauty of Paris has long inspired writers, musicians, and artists, including American architects. Behind this elegant, ivy-draped façade lies an attention to detail that exalts the splendors of France.

Heavy carved doors open onto the cobblestone courtyard of a hôtel particular, or private residence, off the grand Avenue des Champs Élysées, where, centuries ago, horse-drawn carriages invariably waited as enviable ladies gathered to pass the time with needlework or gossip, or sought other means of escaping from everyday constraints.

Some of the city’s most sought-after appartements are tucked behind closed doors, such as these on Paris’s Left Bank.

When botanicals climb the walls, a once-humble powder room takes on new vitality. Houston designer Dianne Josephs found both the antique prints and the artful borders in London shops, perhaps taking her cue from Empress Josephine Bonaparte, who was said to have taken extraordinary care over the smallest detail. Botanist that the Empress was, she had rare species of plants brought from all over the world to her gardens at Malmaison. The carved French commode has a new limestone top. Both mirror and commode are from Joyce Horn Antiques in Houston.

A light and airy garden room in the soft, watery colors favored by Madame de Pompadour sings with French style. The pièce de résistance is, of course, the antique opera seat from Lewis & Maese. (Opera diva Beverly Sills is said to own the matching one, though hers is tufted and upholstered in velvet.) But the room also boasts an antique Italian table, a Haines Bros. piano, and Bennison linen from England. A papier-mâché coffee table adds a note of whimsy. New York City decorative painter Hillary Harnischfeger embellished the walls and ceiling.

An old-fashioned screened porch runs the length of the house, offering a view of the outside world’s seasonal splendor. Meanwhile, a savvy café table plants itself next to softly cooing doves—the answer to the frenzied pace of everyday life. Low-maintenance stone readily handles paw prints and breakfast spills, whereas lanterns add a posh touch.