7. Redistribute Power

Or How to Fight for Fairness and Make Enemies of Exploitation

Fierce fairness

We’re reaching a crucial stage in your pirate journey. Hopefully you already know the mutiny you’d like to begin, hopefully you’re gathering a crew, energy and conviction as you start to believe that you can find new solutions to approach old problems. If you can see change on the horizon then you might already be feeling a rush of excitement. I hope so. If you haven’t got started yet, have no fear, the pirate change framework comes with a rush-of-excitement guarantee; once you begin to put the first stages into practice, you will feel it. But there are some new challenges that come with these early wins. Once your rebellion is a success, no matter how small; once your new rules are being followed, even if it’s only by one person; once you’re collaborating, not growing; once you’ve felt the power that comes from creating change, what are you going to do with it, and how are you going to protect it?

Will you continue to champion the change you’ve caused with unwavering integrity, or will you disappointingly but predictably dilute that difference you wanted to make by succumbing to side deals and compromising your principles to cling on to power?

It’s the implementation of this penultimate of the five pirate principles, the redistribution of power, that will determine whether the change you’re working for will hold true or get blown off course. Each stage is important, but in this chapter we learn how to start to protect all that’s gone before as we see the potency of handing over power, sharing profit and opening up decision-making to preserve our integrity. Any upstart or egotist can rebel, rewrite and reorganize themselves around a cause for all sorts of morally ambiguous reasons, and that’s what makes this step so important; there are many alt-disruptors and ideologues who might appear to be following the first three pirate principles, but what separates us and them is taking the next step to redistribute power and make an enemy of exploitation. If you ensure part of your rebellion is to redistribute power and fight for fairness you protect the cause of good trouble, not just trouble in and of itself.

Power makes a Gollum out of most of us in the end. There’s a reason that revolutions turn into institutions, and heroes who fought for freedom give way to, and often become part of, disappointingly corrupt administrations. Nothing will be different this time unless we set out to share our power differently. The pirates learned this the hard way and saw it in pretty stark terms: redistributing power is the way to protect the integrity of our change and maintain respect for each other in the process. There was no way the Golden-Age pirates were going to fight so hard for a different way of doing things only to let the bad habits of exploitative muggles creep back in, so they designed processes that forced fairness. You can’t grow a mutiny into a movement, organize yourself to react quickly to challenges or achieve great things if you insist on clinging to old top-down lines of command. We like to think we can, but history tells us again and again we can’t. Ask the Zapatistas, Che Guevara, Nelson Mandela or a long list of freedom fighters turned politicians if they’re pleased with how their revolutions turned out. It’s very hard to play nice with power. The pirates protected what they had built from corruption, ego and greed by getting militantly strict about fairness. But make no mistake, they didn’t just get all ‘sharing is caring’ because of a dedication to social responsibility; they knew that clear principles could protect what they’d fought for and give them an advantage.

If you are going to overcome the challenge in front of you, start that thing you’ve been thinking about starting, and take on the world, you will go far further if you view establishing your principles as your foundation. And please, don’t make the mistake that too many people do when they hear words like ‘principles’ and ‘fairness’ – that this is the ‘fluffy’ section that can be skipped. That would be as grave a mistake as believing anyone emblazoning their walls, sweat shirts and Instagram accounts with ‘fluffy’ statements really lives by them. I am always a bit suspicious that anyone who feels they need to remind others to ‘work hard and be nice to people’ is covering up their own inner difficulty in doing just that.

Instead, I suspect the pirate approach was more of a mutual assumption that everyone agrees not to be a pain in the arse as the collective baseline, and from there, sincerely held values and principles become a defining, competitive edge. It’s about deciding what is important, what is your North Star when you’re lost, what is the currency with which you collaborate and negotiate and where the bottom line that protects your authenticity and integrity is drawn. The pirates had this under control – they had to. They were outlaws who had to trust each other implicitly and understand each other’s motivation because their collective survival depended on it. They designed precise mechanisms to make their power equitable and minimize the obvious opportunities for conflict that they’d hated under a command-and-control setting in the navy. They lived by the maxim ‘No prey, no pay’, which meant that every pirate should receive a fair (and in most cases equal) share of everything they stole. They invented workplace injury compensation hundreds of years before any industry caught on and they administered everything relating to money, as well as duties and responsibilities, with complete transparency. Sure, they wanted to be paid fairly (and hopefully fantastically from all that stolen treasure), but they also wanted to be treated equally and participate fully in the decision-making that ran the ship. So they pioneered universal suffrage, elected leaders and came up with a dual-governance leadership structure. Essentially, they valued equality and were prepared to share power in order to achieve and protect it.

Peter Leeson, author of The Invisible Hook, provides a rational economic perspective that may explain their seemingly innovative stance:

Pirates needed to avoid as many opportunities for violent conflict that could erupt into fighting and tear the organization apart. Unsurprisingly the greatest divisive force that threatened this possibility was money. To minimize the chance of natural human emotions disrupting or even totally undermining their profit-making purpose, pirates eliminated the greatest potential source of these emotions, large material inequalities.1

Pirates did not ‘do good’ for the sake of doing good. They were not trying to clumsily ‘give back’, or racked by the existential ‘purpose’ crises many individuals and organizations find themselves in circular conversations around today. Yet they held an approach that could benefit anyone facing that conundrum. They knew what they wanted, they knew what they stood for and they established principles so profound they could rely on them to inform their strategy even in the middle of a fight and amidst the uncertainty of their times.

Pioneers of power-sharing

We’ve already looked at the one-pirate, one-vote model of democracy, but the pirates protected the shared sense of power by going even further, at times allowing captains to be voted in or out by the crew, making their democratic power fully accountable to the people. In The Invisible Hook, Leeson states:

It is truly remarkable to think that this model of democracy was staged not only on a pirate ship, of all places, but took place more than half a century before the continental congress approved the Declaration of Independence and only a little more than a decade after the British Monarchy withheld the Royal Assent for the last time. Pirate Democracy extended the unrestricted right to Pirates to have a say in the selection of their society’s leaders nearly 150 years before the Second Reform Act of 1868 accomplished anything close to the same in Britain.2

The pirates pioneered an early form of democracy that championed universal suffrage and the election of the people’s leader, by the people, but they also had a unique approach to leadership once a captain was in place. The pirates embraced a system of ‘dual governance’ whereby the quartermaster was granted power equal to that of the captain. Under dual governance, the quartermaster was the voice of the crew and culture whilst the captain led the strategy. So far, so very modern management principles.

Just as they handled leadership democratically, pirates had an equally forward-thinking approach to handling income, pay and profit. In the navy, you could sail the seven seas many times over but you might not get paid for it. Pay was infrequent, at the mercy of tyrannical and sometimes thieving captains, and occasionally didn’t happen at all or was replaced by a token system. Indentured or press-ganged men were forced, kidnapped, tricked or even drugged into service without the opportunity to agree a salary in the first place. Those who had previously been slaves had no income whatsoever. In contrast, pirates paid themselves fairly and squarely. On pirate ships, pay was a sophisticatedly simple and decidedly democratic right, with three main conditions:

1. No plunder, no pay.

If the captain and crew didn’t win a prize (i.e. capture and loot a ship) then no one got paid and everyone had to rely on the same rations and reserves to survive. Unlike today, there was certainly no pay for underperforming bosses. Captain, quartermaster and cabin boy all lived, died, ate and got paid under the same principle.

2. Open incentives for going beyond the call of duty.

These differed from crew to crew, but were transparent and clear rewards available to all members of the crew. Being the first to spot a ship on the horizon (be it a prize or a predator) could earn that crew member a reward, such as their choice of any weapon won from taking that prize.

3. Fair shares for all crew members.

All surviving records of Pirate Codes indicate a system of proportional pay which saw the vast majority of the crew take an even share of the booty, whether they were freed slaves, women, boys, drunk or half dead. If they were on the account, they were on the payroll at the same rate as everyone else. Only a handful of senior players like the ship’s carpenter, doctor, quartermaster and captain received a greater but corresponding amount, usually checked somewhere between two and four times larger than the average share. This higher ratio recognized roles of greater responsibility or risk, and it was a transparent transaction that all the crew were aware of, and even played a hand in agreeing.

The progressive ideals about fair compensation aboard pirate ships didn’t stop at pay packets. They also extended into injury in the line of duty, creating a system of social insurance approximately two hundred years before it became standardized around the world. Pirates’ compensation was calculated on a sliding scale that took into account everything from the loss of a leg to a finger being chopped off or an eye gouged out, each being apportioned an appropriate amount. The pirate payout varied surprisingly little from crew to crew or throughout the Golden Age and was universally approximately 800 pieces of gold for a lost leg and 100 pieces of gold for a lost eye, which might sound blunt, or even upside down, but it was a lot more sophisticated and fairer than the rest of the working world. The injury compensation scheme was a case of enlightened interest applying collectively across the whole community. There was collective agreement that introducing some payout on injury was the right thing to do, not just for the leadership but for everyone.

The pirates’ attitudes to power and pay illustrate the undeniable correlation they recognized between transparency and accountability. Everybody knew how much they would get paid and how much they would be compensated for any injury they sustained. They also knew how much everyone else would get paid and they were encouraged to be more accountable by tying together individual and collective reward. It doesn’t really need saying, but I will: that level of transparency around pay is not yet something that almost any mainstream business at almost any level does as well as pirates did.

Not to mention those three little words: gender pay gap.

The pirates’ enlightened approach to power distribution inspires us to fight for what we deserve and expect: equality, a fair share, reward for risk and a commitment to avoid exploitation. Pirates had policies on all these areas to make success and failure a collective act, a powerful technique to align a team and harness the ideas of fairness, self-direction and purpose to become wind in your sails.

Their implementation of dual governance and focus on non-hierarchical facilitative leadership is an especially important lesson to learn today. As the concept of global leadership fails us to the point that it risks becoming oxymoronic, the next generation no longer look upwards for inspiration or wait for power to be handed down to them, and nor should they.

Leadership and knowledge sharing were once always top-down concepts, but they’re shifting to a horizontal perspective as the leadership role models of today are more likely to be peers that you can access than figureheads who seem so far out of reach and out of touch. If you’re seeking someone to look up to in the twenty-first century, instead look sideways to your peers and inwards to yourself, because there’s an absence of inspiring and progressive leadership up ahead.

In mainstream business leadership, original thought and the promise of power-sharing seem, like Elvis, to have left the building, whilst the start-up community, social enterprise and tech and creative economies are thriving because of non-hierarchical new models. It’s no surprise that millennials are ditching postgrad jobs to found start-ups, or that, according to UK headlines, in 2017 ‘there are now 311,550 company directors under the age of 30, up from 295,890 just two years ‘ago’ gracing Britain’s economy.3 These are UK statistics, but show a significant trend which plays out internationally. Rather than hang around for years waiting to inherit power, a new generation is heading out to take it and make it for themselves.

But it’s not just business leadership that’s failing to meet the next generation’s appetite for a fairer approach to power. In 2016 both the UK and the US saw a surge of youth excitement for two left-wing outliers advocating policy that many thought to be consigned to the history books. Septuagenarian socialist Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn’s unlikely youth appeal can be captured in the metaphor of their creative hashtags #FeelTheBern and #Grime4Corbyn. There was unprecedented support for this pair of elderly white male politicians amongst the younger generations principally because both seemed a) honest and b) to give a shit. More than any great political statement, this shows a) what the next generation values and b) the vacuum of credible alternatives. Individual businesses and politicians can succeed despite an apparent lack of innovation and entrepreneurialism, but it is the absence of optimism and empathy in the system as a whole that might cause fatal damage to the broader structures of conventional mainstream society, in the hearts and minds of the coming generation who expect compassion.

Finally, there is a shift taking place from blind capitalism to woke consumerism. The Aspirationals report is the result of a partnership between New York-based consultancy BBMG and global research company GlobeScan. From representative research in over twenty countries, the report categorizes an emerging mindset they named the ‘Aspirationals’ who are defined by not just a desire for but also an absolute expectation for ‘Abundance without Waste’.4

They want the same products and services we’ve all grown up with, they want quality and convenience and cool stuff, but they also have laudably high expectations for how it’s produced, where it’s from and what the impact of its journey into their lives is. Action on corruption, environmental damage and fair treatment of staff are all at the top of the Aspirationals’ expectations of the brands they’ll buy from. And this is not a radical or alternative group. This is me and you. They want the new trainers, the latest tech, and to be able to go out and enjoy themselves. They just don’t expect to do it at anyone else’s expense. It’s not a mindset defined by age, nor is it grouped to any particular geography or ethnography. It’s completely global and across the two reports, three years apart, it’s a group who are growing.

The Aspirationals are a ‘billion-dollar paradigm shift’, where the power has been returned to the customer. The report cites Tom LaForge, Global Director, Human & Cultural Insights at the Coca-Cola Company: ‘The harder we compete, the less differentiated we become. As brands sell on functional benefits (what the product is and does for me) and emotional benefits (how I want to feel in this occasion), category after category is being filled with nearly similar products. Large established brands are losing loyalty and market share to newer smaller brands that offer social and cultural benefits.’

Raphael Bemporad, founding partner of BBMG, who conceived of and oversaw both studies, neatly sums up the international Aspirational mindset: ‘With Aspirationals, the sustainability proposition has changed from being the “right thing to do” to being the “cool thing to do”.’

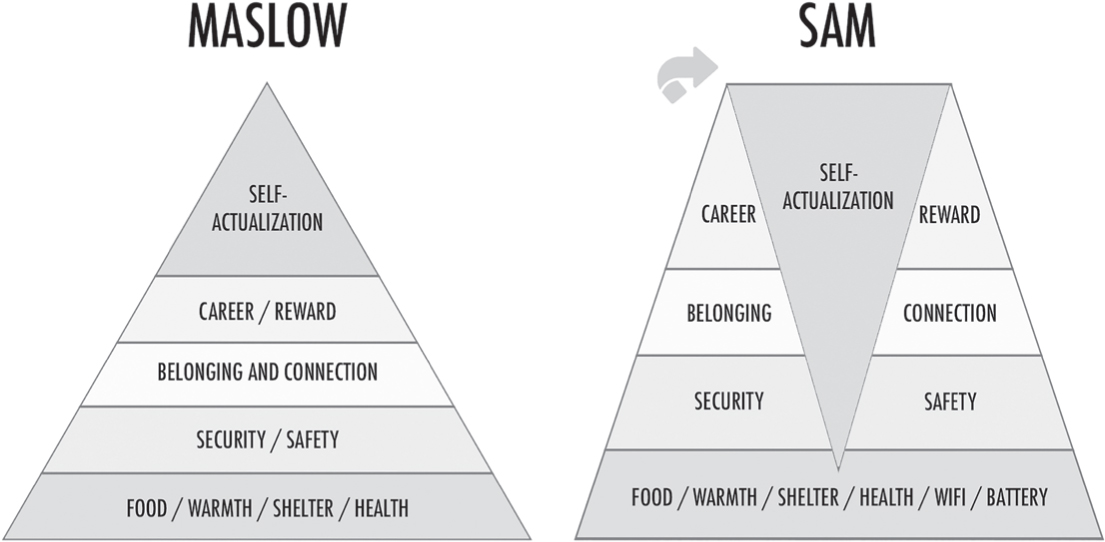

The Establishment’s thinly veiled self-absorption holds no appeal to these open-minded minds of the future, who want answers, ideas, self-determination and self-actualization. And herein lies the clue: self-actualization, the famous pinnacle of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the locus of a thousand leadership books, essays and TEDx talks, and a recently reproven mainstay in our understanding of why we do what we do, and what we’ll do next.

Back in 1943, Abraham Maslow charted a human being’s progress through life via a series of ‘need’ states that we attempt to work our way through. Like all good ideas that explain everything, his model is drawn as a triangle.

Pretty much ever since this idea was formulated, we have accepted the notion that we think about morality and the common good only once we’ve conquered the rungs of property, prosperity and security. The idea is we only begin to give back or meditate on our higher purpose once we’ve made it to the top of the pyramid.

But that’s the old paradigm. In the new paradigm, there are people whose mindset is to ponder the value, purpose and meaning of just about everything from life to work and the balance in between, and as a result they are self-actualizing long before they’ve climbed that elitist pyramid. Many don’t arrive at a point of ‘giving back’ because they never ‘took’ in the first place.

In light of this, I’ve given Maslow’s model an OS update to bring it into the twenty-first century. There are two essential upgrades. First off I’ve included WiFi and battery life at the base of the pyramid along with food, shelter and warmth, because, like, durr.

Second, I’ve tipped the top of the triangle – the bit when we have our ‘Aha’ moment and realize there’s more to life than accumulating stuff – inwards and downwards. It is my profound observation and belief that for a new generation, self-actualization actually begins at the beginning.

Over the last two decades, I’ve worked with thousands of young leaders from different countries and cultures who collectively represent the future of leadership. Whether they are urban or rural, middle-class or marginalized, their desire to do something meaningful is extremely strong and kicks in early. The much-quoted Millennials Survey produced by global consultancy firm Deloitte supports my Maslow hack: Barry Salzberg, CEO of Deloitte, states: ‘Millennials are just as interested in how a business develops its people and its contribution to society as they are in its products and profits. This should be an alarm to business, in the way they engage Millennial talent or risk being left behind.’5

Rather than feel pessimistic about current power structures who have vested interests and will protect themselves unto their dying breaths, which in some instances might be better occurring sooner rather than later, I look forward to the next wave of leaders whose understanding of purpose, responsibility and ethics is more developed than any generation gone before. For them, meaning matters. ‘Giving a shit’ has gone from being a nice-to-have outlook to a need-to-have belief.

In a similar shift towards the practical, the pirates turned a profound belief in values into weapons-grade decision-making techniques and turned hard-and-fast principles into a ruthless competitive edge. In the same way, organizations wanting to make the most of this new mindset need to move from platitude to attitude when it comes to a clear sense of purpose. They need to recognize that breakaway talent of this age thinks that the best work of their lives will also be the most meaningful work of their lives.

The younger generations coming into the workforce now are naturally more pirate than their predecessors. In order to make sure the new importance they place on meaning and purpose is heard and acted upon we need to establish new structures that will allow for more collaboration and fairer distribution of power and profit; we need to evolve from the generic twentieth-century business model that was in some ways always built on a degree of exploitation of either their own supply chains and human capital or someone else’s creativity or natural resources.

Social enterprise: undercover pirates

Of course, there are already organizations run using an enlightened approach that is both innovative and impact orientated, and they’re called social enterprises. If you’re unfamiliar with the concept, the term might sound a little bit do-goody, a little bit less serious than non-social enterprises, but that impression would be mistaken. I would argue that social entrepreneurs are modern pirates in all but name. A social enterprise is essentially the combination of a very typical business or enterprise model (one that makes money) and a social objective (one that makes a difference). Whilst social enterprises are often income-generating organizations, they don’t exist solely to generate profit for shareholders; they share profit and power more fairly than most companies, which in turn makes them more innovative and effective. Overall there is a pirate-like dedication to independence, proving alternative systems and fairness and generating income in a way that’s not reliant on the state. (Apart from the plunder, to my mind they’re cut from the same cloth.)

The social enterprise name has been around since the 1980s, when it arose as a rebellion against the ‘greed is good’ era of capitalism but it’s begun to tip into mainstream business in a big way. Social enterprise now accounts for approximately 7 per cent of all businesses around the world, and as the UK State of Social Enterprise Report 2017 confirms, the sector is out-innovating, out-investing and out-performing its purely commercial equivalents, with higher rates of diversity, pay equality and performance, and, of course, all whilst creating positive impact. In short, social enterprise is a thriving international hybrid industry, filling the gulf between big bad business still hooked on growth, non-efficient NGOs fundraising themselves into existence and government policy that can’t see past its next election.

There’s no wonder social enterprise is doing well, because it taps into (and helps to drive) the shift in values we’ve been looking at, where doing something that means something is all-important. As the entrepreneur, author and prolific force of positivity Afdhel Aziz likes to say: Good Is The New Cool – the title of his book in which he makes a watertight case for it. It’s a neat summary of the coming zeitgeist; partly entrepreneurial, partly socially conscious and partly about self-actualization. And, whereas a combination of those three attributes might have made someone in the past partly worthy, partly wishy-washy and partly exhausting to hang out with, these really are characteristics that have joined the classic aspiration set that people want to adopt when they grow up, as Afdhel himself demonstrates in both his timely title and as a high-profile, jet-setting public speaker and purpose-driven entrepreneur.

In 2001, when I co-founded Livity, now an international and multiple award-winning social enterprise and youth-led creative network, I thought I was some sort of pirate-pioneer inventing a new type of business that would make both a difference and some money; I was simultaneously embarrassed and elated when I realized I was, in fact, just arriving late to the party of a global movement that was already in full swing.

Livity began as an experiment to discover whether ‘ethical marketing’ was an oxymoron, and whether it was possible to bring the budget and influence of brands to create advertising campaigns that would tackle issues that mattered to their audience whilst still delivering on commercial objectives in a happy sustainable marriage of mutual benefit. Our ambition was to redistribute power and transfer authority away from the big brands who usually like to do the selling, to their young audiences who normally like to do the buying. Or, to put it another way, we set out to discover whether you could re-educate brand managers to grow their business by seeing young audiences as their responsibility as well as their opportunity.

At the time, the power dynamic between young people and brands was a one-way street. I had spent the last six years running nightclubs, raves and events and setting up a creative agency and platform called DON’T PANIC from my bedroom. As the music we loved went mainstream, big brands wanted a piece of the action, and as I began working with them I discovered something that surprised me. Huge numbers of extremely smart and emotionally intelligent people were working overtime with every ounce of creativity they had, spending huge amounts of money desperately trying to create a connection between young people and chewing gum, hair gel and all the other pointless stuff that no one really needs. At the time I was devastated; I’d finally arrived, but no one with any power was remotely interested in using it usefully. The problem seemed clear and inescapable so I decided to launch my own rebellion in the form of Livity.

I wanted to take back the power on behalf of the victims of irresponsible marketing. When a brand’s core value is ‘happiness’ or ‘winning’ and it directly targets a young, vulnerable and low-income audience with messages that are deeply sophisticated and powerful at saying, ‘If you want to be happy or a winner, buy this shit you don’t really need for more than you can really afford,’ young people are in danger of confusing materialism with meaning. This might not be as damaging for the brand’s main audience who are generally affluent, well educated and quite possibly more able to see through the charade, but it can have a profound impact on young people from turbulent, less-educated backgrounds with less money and less experience, who confuse the belonging you can buy with the sense of belonging they need, and as a result make a neurological link between important emotions and unimportant promotions.

At the other end of the spectrum, well-meaning charities and government agencies occasionally tried to talk to the same young people about things like sexual or mental health, careers or keeping out of gangs, but it was often patronizing and out of touch and served only to make the commercial messages appear to be the more compelling solution to their problems.

And so it hit me: the empowering and informative messages most likely to effect a positive life outcome (like avoiding debt, or improving diet) are communicated so poorly they make matters worse, whilst the things that they need the least (like fizzy drinks and £200 trainers) are communicated so effectively they fulfil a missing part of who they are as human beings. From that day forward I realized that people in the business of marketing, media, advertising, PR or communications could either choose to be part of the solution or they were part of the problem, and that there was little middle ground.

At the time, this was not a conversation brands were having, Enron were still pin-ups of corporate social responsibility and, whilst it was the year Naomi Klein’s book No Logo was published, it was still seen as anti-brand, and my idea for Livity was definitely pro-brand AND pro-society. I decided to draw up a list of the smartest people in London’s marketing industry, people who might ‘get it’ and have a good idea of how to right this wrong. I met Michelle, who is now my business partner and who, with more of a formal agency background, had arrived at pretty much the same conclusion as me. We immediately organized ourselves as quartermaster and captain, equal partners, equally rebellious and equally pirate in nature. We raised the flag of Livity and put the word out that we were beginning a mutiny.

At launch, Michelle and I scraped together the money we could, around £10,000, and we calculated that it would buy us three months of a basic wage, office rent, phone lines and an internet connection for email (you didn’t even need a website in those days). Our rationale was that if we couldn’t sell the vision of our marketing rebellion in three months and win a client, then there probably wasn’t any value in the idea of an ethical marketing agency after all. Years later I learnt this is actually a widely used management strategy called a ‘burning bridge’, whereby you set an inescapable end date to your endeavour to create a sense of urgency and prevent yourself from endlessly chasing the dream. Thankfully, in the last week of our third month, we closed a deal that would see us through our first year.

Two things came to define Livity: the first was a relentless focus on creating only marketing campaigns that delivered on shifting the power between the brand and the audience benefit; the second was the decision that members of that same young audience would be given the keys to the business. Literally.

From Monday to Friday, from dawn to dusk, young people from all backgrounds, walks of life, classes, cultures and degrees of chaos were able to access the Livity office as if it was their own, and pretty soon it was. They came to work on our in-house publication, Live magazine, which was produced entirely by young people, entirely for young people.

Live was protected from the commercial pressure facing the rest of Livity, and the young people were given autonomy and editorial freedom, as well as expert professional mentoring to protect them. From interviews with crack dealers to uncovering the next ten years of underground artists, to an ever popular (with older people) slang dictionary to investigations into all the taboo topics of youth from sexuality to religion, gangs, racism and policing, it was honest, entertaining, inspiring, authentic and a centre of gravity that brought thousands of young people through our doors, and in turn helped them launch their careers.

In return it meant our ideas for our clients were the most insight driven, strategically rooted, honest and effective campaigns they could be. Those young people used the Livity office to start up businesses, begin their careers, do their homework, rehearse plays, write books and much, much more. Livity provided more than just space for them, but leading-edge technology, desks, computers, studio facilities, mentors, workshops, career advice and even social work support around housing, benefits and more. Many young people ended up using Livity as a launch pad for life, allowing them to escape the systemic lack of opportunity they had so far experienced.

Into this noisy, high-energy, chaotic and creative environment we invited our clients, who became infected with the passion, idealism and energy as a return on investment. Livity’s clients include PlayStation, Google, Netflix, Facebook, Unilever, Barclays Bank and many more. But even more impressive than a roster of iconic logos is the work our young people led for them to develop successful solutions to issues including online bullying, relationship abuse, sexual health awareness, financial literacy, access to employment, future skills and tackling extremism.

Not all of Livity’s initiatives were successful, and we faced some of the hardest obstacles any organization can face, like making redundancies, losing pitches and, worst of all, when the challenges they faced would overwhelm one of our young people. But, through it all, we held true to our purpose.

We’d built Livity based on passion, for revolution, for change, to make great work, for the creative, impactful, inspiring output and to empower young people.

And I think this has been the key to Livity’s success ever since, across the UK and in South Africa. We defined our values in actions. For many clients, we’re the only agency they visit where they aren’t the most important people in the room, but take second place to the young people to whom we’ve so successfully distributed power that they have become indispensable.

Empowering young people to shape, design, lead and generate great creative work that is not only funded and respected by brands they love, but also makes a difference to their peers, has a transformative effect on everyone involved in the process. We’ve been called a ‘transformation engine’ by the young people whose lives we’ve changed, and that idea of a transformer, or devolving power, redistributing energy and accelerating young people’s potential is what defines Livity still, almost twenty years later.

If I sound a little bit proud, that’s because I am. I am proud of the hundreds of thousands of young people who have worked with Livity and changed their lives through their own initiative and ideas. Livity gives power to all and champions fairness in every opportunity it pursues. It raises the flag of rebellion, embraces an alternative way of doing business, magnifies its importance and effect through its collaboration with young people, not through growth, and it creates a safe space where everyone enjoys shared power and fights for fairness, pirate style.

Pirates in a sea of waste

There’s no shortage of pirate-like social enterprises living out the ideals of redistributing power, making an enemy of exploitation and fighting for a fairer, more sustainable twenty-first century. A captain amongst such positive pirates is Kresse Wesling, CEO and founder of Elvis and Kresse.

Wesling says she’s always been fascinated by waste, even as a child; going to the dump with her dad she’d see beautiful old things in need of someone to repurpose them where other people simply saw rubbish.

In 2005, Wesling had been thinking about setting up a business in repurposing waste, but she wasn’t sure what type of waste she wanted to use or what her end product should be. Then she happened to meet some people from the London Fire Brigade on a course. From them she learned that damaged fire hose is thrown away as waste. Made of thick rubber, fire hose is pretty much the least recyclable thing known to humanity and was adding to the huge problem that is overspilling landfill sites. She realized that waste fire hose was the raw material of her dreams, and that this was a big problem that she was sure she could help solve.

Wesling scraped together some basic funding to get started and convinced the London Fire Brigade that it would be better to give her the decommissioned hose rather than pay to send it to landfill. She promised them that if her idea worked she’d give them 50 per cent of all her profits.

At first Wesling thought the hose might make good roof tiles for sheds. She was wrong. Research revealed that cut hose is no longer fireproof, and after ten years it would crack. Leaky flammable roofing was not a winner. But then she turned her eye to sustainable fashion and settled on bags. When she started to look for someone who could help her transform the waste hose, she realized the craftspeople with the necessary skills to work on such a tough material were diffuse, mostly in mainland Europe and not keen to work with what she had to offer. After a lengthy search, a partner with the requisite top-end craftsmanship pedigree was found. She finally persuaded this manufacturer to work with her, and together they produced a collection of beautiful handbags and wallets that combined ethics and aesthetics, waste and luxury. One of her early wins was persuading Apple to let her make a reclaimed fire hose iPhone case, that was stocked exclusively in their flagship London Apple Store. When a stylist picked one of her belts to use in a photo shoot with Cameron Diaz that ended up on the cover of Vogue, Elvis and Kresse found a new meaning of power for their products.

Once she had been recognized by one of the most powerful platforms in the hard-to-infiltrate world of high fashion, Wesling knew how to use that power and built her own brand whilst diversifying into new and more difficult waste products. Now, Elvis and Kresse reclaim ten different forms of waste, including the sacking that coffee beans and tea leaves are shipped in, offset printers’ blankets and parachute silk.

The company is run as a social enterprise, meaning it’s entirely independent, it generates its own trading income and uses its profits partly to fund growth and partly to donate to social and environmental causes. It was founded on the dual basis of fixing a problem, in this case an environmental one, and developing a product that would make a profit. The promised 50 per cent of profit on the fire hose was and continues to be duly transferred to the Fire Fighters Charity. That original pledge has mutated into one of three measures the company uses to evaluate success: not just the financial bottom line but also how many tons of waste are diverted from landfill and how much money is donated to charity. It is a transparent organization, welcoming visitors to its offices and workshops. Elvis and Kresse has shifted the manufacturing skills it needs back to the UK by training apprentices, so more of its lines can be produced domestically, and the operation is run entirely on renewable energy.

Wesling has so much restless energy and radical intention that she could teach most pirates a lesson. She generates ideas at a rate of knots and relentlessly hunts down solutions. She’s totally unsentimental about wanting to do good, and she makes doing good look incredibly stylish. She attributes her success to her small team of people who are as invested as she is in honouring the raw materials, the process and the customer.

And the moment Wesling knew that Elvis and Kresse was a success was not when her product made the cover of Vogue, or because of the numerous social enterprise awards and recognition she received from celebrity clients and No. 10 Downing Street, it was when she realized that she’d basically made herself (or, more accurately, her handbags) redundant. By 2010 the business was sustainably using all the country’s waste hoses; as long as it keeps doing so, the hose problem is solved. Some people might feel a little anxious if the source material of their most iconic product were thus limited, but not Wesling. She’s now working with firefighters around the world, taking delivery of their waste hose, and at the same time she’s on to the next thing: taking on the colossal waste problem in the luxury leather industry. At the end of 2017 she announced that she was going into partnership with Burberry Foundation to reclaim 120 tonnes of Burberry leather scraps over the next five years and turn them into new products. She’s found a new, even bigger puzzle to solve.

Wesling’s story epitomizes the idea that, by rigorously redistributing power, publicly and accountably, the purity of a strong idea can be protected and accelerated as it compounds, growing its impact as it does. Wesling deftly devolves power to a wider group of suppliers, stakeholders and customers, making them all complicit in achieving the goal whilst also making them all protectors of the vision.

Just like our Golden-Age pirate predecessors, we find ourselves in uncertain and unfair times but with a fundamental desire to do things differently. We’ve seen that, even with the energy of rebellion, a keen crew and cutting-edge reorganizational skills, until there’s a shift in power dynamics away from hierarchies and towards collective and representative models, our ability to change things is limited. Like the Golden-Age pirates, we need new values, clearly articulated, to replace the old ones that worship financial profit above all.

When you commit to redistributing power and fighting for fairness, you take the single most radical and effective step towards making your change a long-lasting success. When you give power away it will flourish and multiply. Other people will be inspired by your actions and will start to follow suit. Inspired by innovation, the mainstream will begin to adopt the behaviour of pirates like social enterprises who start out at the edge. It was pirates’ collective effort and focus on both financial and social justice that allowed them to thrive and take on the world.

Their sense of mission or ‘purpose’, their crusade against unfairness and their ability to influence change, whether implicit or explicit, was a fundamental component of the pirates’ success, their legacy and their impact. It was their clarion call, and it was heard the world over.

If we’ve learned anything about pirates, it’s that their practices are often an accurate prediction of how waves coming from the edges of society will influence the mainstream. I would bet all my pieces of eight that the tactics and techniques of transferring power that are making the modern pirates of the social enterprise movement so successful and so attractive to work for are a rising wave that will become mainstream practice within my lifetime.

In fact, pretty soon, I suspect, any organization operating by any other standards will begin to be perceived as a distinctly anti-social enterprise.