11. The Pirate Code 2.0

Steal like an artist

By the end of this chapter you will have the beginnings of your own Pirate Code that you can add to and adapt as you see fit, mission by mission, side hustle by side hustle and adventure by adventure. You will have a basic but bespoke framework for your own Pirate Code – a whole new way of getting things done, a guide to making clearer, faster and better decisions based on what really matters to you, and your crew.

When exciting opportunities and death-defying deadlines rush towards you, your code will allow you to stay calm and clear-headed as they whoosh overhead and into view. When the rules of the game change, and not in your favour, leaving you without time to think, your code will help you remain responsive whilst also holding firm to your course. When your to-do list ties knots in your abdomen and your inbox makes you want to scream at your screen, your code will help you cut through the crap and get directly to the gold.

And don’t worry. The first steps to creating your Pirate Code are very simple. A successful Pirate Code is all about adoption and adaption, choosing and cherry picking which articles might work for you. In other words, you’re going to start by stealing someone else’s.

In the spirit of being more pirate I’ve stolen some other people’s articles, for you to steal from me. When it comes to creating a code that’s going to help you change your world, in true pirate fashion steal anything and everything that works for you. As the legendary filmmaker Jim Jarmusch is widely quoted as saying, ‘Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent.’

Just make sure that when you do steal, you always steal the best, and try to make sure you stay on the right side of stealing so you don’t wind up with a criminal record.

Looking to a wide range of modern pirates for inspiration, I have pirated the very best for you, creating a source code that I’d be happy to live, work and die by, and that hopefully you’ll find something you can draw from. I’m very lucky to spend time in the space between business, policy, entrepreneurship and social change; it’s an intersection that sees some of the world’s best solution-focused innovative, imaginative and impactful individuals, organizations and ideas. This is where I’ve sourced my suggested starter articles from that you can use for the foundations of your code, choosing to save or scrap any of the ones I’m about to present.

When it comes to big ideas, it might not always be apparent, or even important, how big the potential consequence of the idea is, only that it’s a big deal for us, for you, for now. As we’ve seen, for the pirates being paid fairly, for instance, seemed like a great idea for them; they didn’t think they were starting a fair pay debate that would last three hundred years. In much the same way, being compensated if you were injured felt like the right thing to do for their democratic community, though they probably didn’t imagine it was going to become a human right a few centuries later. Like the pirates, we don’t need to worry about creating articles that will stand the test of time and change the world, we just need the ideas to work for you, now, and following the paradox of scale, the right ideas made to work really well for a small group might just become those that end up having an impact on everything. The codes protected the integrity of the pirates’ ideas, kept them authentic as they lived them and ensured that, even over decades, they held true to their intentions, whilst their ideas compounded and eventually took hold at a much broader level. Big ideas, small steps. Take what works, make it work for you and watch it fly.

Victor Hugo, one of the greatest French writers of all time, and author of Les Misérables, the world’s best-known depiction of the French Revolution, was a firm believer in the unstoppable force of human progress. Whilst in exile from France under Napoleon, he observed: ‘There is one thing stronger than all the armies in the world, and that is an idea whose time has come and hour has struck.’ I held this thought in mind as my benchmark when I sourced the following articles for you – I was looking for ideas whose hour had come, and that one day could compound as far as the pirates have.

At the end of the chapter I’ll show you how to assemble your set of articles to create your code, but for now, sit back and take in the codes I’ve selected for you. As you read each suggested article, consider the following questions to decide whether you should include it in your own Pirate Code 2.0: Does this article reflect values I respect? Can it give me an edge against my rivals? Could it help me make better decisions? How would I feel if I knew the rest of my crew were living by it? And lastly, possibly most importantly, does it, or part of it, really excite me? If no, move along; if yes, or partly yes, steal with glee.

Stolen Goods:

Introducing the Articles of Sam Conniff Allende’s Pirate Code 2.0 – 2018

Article 1 – Make Shit Up

THE CHALLENGE

We need to get good at making things up responsibly, immediately and decisively. If we’re going to keep up with the unpredictability that regularly outpaces us, we need licence for mature but in-the-moment application of imagination. We need to reduce an overwhelming reliance on chain-of-command thinking, a dangerous default to data-always-knows-best, risk-averse and rulebook decision-making, and empower individuals within all our organizations to try stuff out in the search for new answers to old problems. We need to be clear about the differences between being fake and being fast.

When the truth is that no one knows what’s coming next, there is danger in relying on rules that were made for a time that’s been. We need to think on our feet, and for ourselves, to critically assess what’s ‘right’ when things change and know when not to follow the crowd or tolerate lies.

We need to evolve the notion of a feeling in our ‘gut’ from sounding like some sort of last-ditch reassurance, to recognize that in an experienced individual a sharpened and honed instinct is amongst our most valuable resources.

Just as we’ve come to terms with the idea of Emotional Intelligence, and the importance of empathy within organizations, so too do we need to recognize the significance of intuition, another easily overlooked ‘softer’ skill that when carefully applied can provide a consistent edge to decision-making.

We need to be able to look each other in the eyes and admit that more often than not, we’re making it up most of the time anyway, so we should collaborate and make it up better, together.

SUGGESTED ARTICLE

All captains and crews profoundly expect, respect, celebrate and appreciate the art of strategically, structurally, intuitively and instantly making shit up. Not irresponsible imaginings, reckless reimaginings and certainly not false or fake news. We champion creative solution finding and positive problem solving based on available facts, the moment of opportunity and the power of practised intuition. When indecision is not an option, when change is constant and nothing is normal, we’re proudly comfortable to rationally and rapidly develop, test and implement solutions on the spot. We learn from our mistakes, even if we don’t celebrate them, and use them to make making it up better.

INSPIRATION

The idea that failing is a positive thing has gained more traction in recent years. How can you argue with Google’s law of failure, the understanding that nine out of ten ideas fail, so if we fail faster we get to the good idea quicker? I, like many other people, really bought into this idea. Fail fast, fail better. It felt cool, a bit edgy, and was a great line to throw into conversation, presentation or pitch deck.

Only it didn’t come true. No one really likes failing and very few people have the real nerve to celebrate it. So once we tired of the cool posters it began to feel incredibly disingenuous. The nail in the coffin for me came at a leadership retreat for one of the world’s biggest companies that was facing disruption on every side and striving for innovation within. I was speaking to their ‘fast track’ talent at a three-day retreat and providing stimulus to drive more innovative thinking and working. One of the up-and-coming execs, a super-sharp future leader of the organization with ground-breaking ideas, held the most senior people in the business to account on this very point. ‘OK,’ he said, ‘I’ve got lots of ideas and can see solutions you can’t. I’m grateful to be in this position, but can you give me your assurance that I can put my ideas into practice and fail nine times and still keep my job and your support all the way to my tenth idea and success?’

Of course, they could not, so he took his ideas and left. Those ideas were revolutionary and will be industry changing when he finds a home for them. The company in question remains one of the top fifty in the world, but has just posted profit warnings. Again.

The Pretotyping Manifesto, which we touched on earlier in Chapter 5, is a very helpful approach that enables anyone to make something up, test it out and create a conversation around an idea that might just help bring it to life. Pretotyping is the stage before prototyping, which used to be the thing you did first but now, thanks to Alberto Savoia, the man who came up with Google’s Law of Failure, there’s this even earlier stage that allows a safe space for making shit up as the first stage of making shit happen.

Savoia asks you to ask yourself what’s the version of your idea you can make for no or low cost, on your phone or with paper and pens. Take a look at the manifesto for inspiration, not least to find out how a broken chopstick and piece of wood can test an idea that revolutionized technology without costing a penny.

The point is to create a pretotype model so that you can see what it looks like, feels like and might be like. It’s smart, fast, fun and anybody can apply it. I suggest you do, often. For more on this, visit www.pretotyping.org/.

WARNING

The art of making shit up has an emphasis on the ‘making’: making it happen, making it real, faking it until you make it, etc., and this is where the article really aligns with the principles of pretotyping, encouraging you to grab any of thousands of free online tools and platforms and see what your ideas look like, when you make them up.

- If you want to see if a product concept will find an audience, but can’t afford the research and development, mock up a Kickstarter campaign or take a look at any crowdfunding site; you might find an audience and the funding you need to make it happen.

- If you have an idea that needs a community to form around it in order to get going, try writing it up and putting it on Eventbrite or Meet Up, even if it’s only for a handful of people or even to see how it looks.

- If you’re thinking about running a campaign, why not test an online petition, set a target, and see if you can beat it, whether it’s ten or ten thousand signatures.

- If you’re not sure if your idea is strong enough to be a real company, spend a few hours and mock up a couple of website pages using templates on WordPress or Squarespace, and see what it looks like, how it feels, and test it out on some friends.

- If you want to bring down a corrupt national organization, first try starting out by running a cheeky hack on a low-level unsecure local office;)

Article 2 – Business Plans Are Dead

THE CHALLENGE

We need a more fluid and flexible way of setting out our hopes, ideas and dreams and a more motivating way to manage and measure ourselves to achieve those dreams than the anachronistic, static (and, if we’re really honest, often ignored) ‘business plan’ allows.

The ubiquitous ‘business plan’ format has overstayed its welcome. Created over a hundred years ago, its template has stagnated whereas what ‘business’ means, how it looks and its relationship with the economy, society, the environment and the individual has transformed. But the blueprint, with its intrinsic old-world tactics, is still the default response to anyone with a big idea that they want others to take seriously, even if ‘business’ as a term no longer does justice to the diversity of your creativity, to your hustle, to your ideas or ambitions.

Of course, there is still a need to assess the opportunities for your ideas to flourish in the future and create responsible growth plans and protect them, but there is also a need to do so just as fluidly as the environment in which you are operating is changing.

SUGGESTED ARTICLE

We challenge a century-old static format as the best structure for the fluid future of our organizations, projects, dreams and schemes. We believe in a motivating manifesto that makes clear our vision and we follow a concise but responsive roadmap with agile measures of accountability. We believe in collaborative ‘working’ and adaptive formats that are regularly used and reviewed in collaboration with not just the whole crew but even our customers, beneficiaries and stakeholders, to openly evaluate success, failure and future scenario planning. No captain will produce a ‘plan’ for only a narrow audience, or a moment in time, only for it to gather dust in an inbox ignored or unused by the crew.

INSPIRATION

I have long suspected that the process of business planning is subconsciously a mutually agreed act of self-deception between the writer and the reader. I’ve known countless young people whose ideas defy their older and ‘wiser’ investors’ and mentors’ imaginations and who literally have to lie through their teeth to satisfy grown-up demands for reliable predictions in what we all know to be unreliable environments and times. These young people, with their strong, curiosity-driven unformed ideas about how to redefine the future, are given the limiting, twentieth-century template of a ‘business plan’ to help them shape (suffocate) their idea into a format that older (less imaginative) experts can get their head around.

With this in mind, I asked a group of young social entrepreneurs who are at the cutting edge of innovation, the type of young people I think of as modern-day pirates, what their approach to ‘business planning’ is. Lots of responses included technologies like Trello, Telegram or Slack, where a plan is more like a thread of conversation, evolving beneath a shared vision, that can be edited and improved as it evolves.

But it’s the overall approach that’s important, not the tool you use to execute it, which was made clear for me when I heard the challenge ‘Business Plans, Grandad?’ from a young social entrepreneur who then educated me in ‘Manifesto Jams’ where ‘dudes with ideas get together to jam their manifesto’ to ensure it gives their crews the motivation and decision-making framework they deserve and need.

Manifesto Jams.

Grandad.

Busted.

The people at the leading edge of this conversation are responsive.org. They have an amazing Slack group you can join to help shape their evolving and electrifying thinking. Here’s how they describe themselves, from their own manifesto:

Most organizations still rely on a way of working designed over 100 years ago … Tension between organizations optimized for predictability and the unpredictable world they inhabit has reached breaking point … Workers caught between dissatisfied customers and uninspiring leaders are becoming disillusioned and disengaged. Executives caught between discontented investors and disruptive competitors are struggling to find a path forward. And people who want a better world for themselves and their communities are looking to new ambitious organizations to shape our collective future. We need a new way. There’s a reason we’ve run organizations the way we have. Our old command-and-control operating model was well suited for complicated and predictable challenges. Some of these challenges still exist today and may respond to the industrial-era practices that we know so well. However, as the pace of change accelerates, the challenges we face are becoming less and less predictable. Those practices that were so successful in the past are counter-productive in less predictable environments. In contrast, responsive organizations are designed to thrive in less predictable environments by balancing the following tensions:

| More Predictable | ❯ | Less Predictable |

| Profit | ❯ | Purpose |

| Hierarchies | ❯ | Networks |

| Controlling | ❯ | Empowering |

| Planning | ❯ | Experimentation |

| Privacy | ❯ | Transparency |

WARNING

Business plans are not yet extinct, so at some point you will be asked for one, and you’ll need to show something to investors, banks or anyone else trying to work out whether they can take you seriously. The best advice I’ve had is to keep a plan as short and as honest and as close to a reflection of your genuine vision as you can. Create it in as much collaboration as you can, with the team and ideally even with your target audience and other trusted stakeholders. Do not let it become an exercise in convincing someone else to believe in it. Avoid the three main risks of conventional ‘business planning’:

- Stifling the magic and unquantifiable energy of your idea by forcing it into someone else’s template.

- Creating a plan that is out of date in three weeks (if you’re lucky) because something more interesting and relevant came along.

- Losing touch with your crew, customers, culture and reality because you’re falling into an existential crisis loop aka business planning.

If you want to get to the core of what your plan, or manifesto, should be so that you can ‘jam’ it in the most direct manner, then pick up a book called Start With Why by Simon Sinek – or, if you’re short for time, watch his TED Talk (the third most viewed TED Talk of all time).1 Read/watch it and you’ll come back with such clarity of purpose you’ll be unbeatable and be able to replace flaky forecasts attempting to predict the unpredictable with bulletproof reasons why you do what you do, and a clear and compelling core to build your success on.

Article 3 – Make the Citizen Shift

THE CHALLENGE

We need to improve our individual and collective relationships with the world and its natural limitations. We need to develop from an unquestioning consumer mindset to one where we question, demand and understand the impact of our choices.

Consumer has become the definition of not just who, but what we are. It is a descriptive and prescriptive term for humanity allegedly at its peak.

Once, long ago, we were all ‘subjects’ in service to our rulers. This idea defined who we were in society for centuries and was only really upgraded in the twentieth century when we evolved into ‘consumers’. Consumer thinking has since dominated in the developed world and as consumers we have become the passengers of capitalism, fuelling its engines and creating decades of growth and a valid belief in the benefits of mass globalization. Consumerism, however, has now passed its sell-by date.

Branding ourselves as consumers is a clear sign we are no longer in charge, but instead are subservient to short-term and self-interested goals, drawn from limited options that are seemingly on special offer.

At a macro level, the principle of the consumer no longer fits in a world that’s so far over its capacity – the one-way relationship of consumption has a limited life expectancy.

On a micro and individual level, social experiments that stimulate a ‘consumer mindset’ in participants have proven that even the single use of the word ‘consumer’ can prompt reactions that are more selfish, less open to participation and less motivated by environmental concerns.

As billions more of the global population enter a consumer mindset of middle-class aspiration, and we accelerate past a planetary point of no return in a system based precariously on debt we can’t afford and in a world without resources to sustain us, there’s a chance the clue to survival is in how we perceive ourselves and the relationship we have with our planet and one another, and it just so happens that the name consumer may well be the signature on humanity’s suicide note.

SUGGESTED ARTICLE

It’s time to evolve the human race beyond the mindset of solely a ‘consumer’ and the dangerous, destructive and limited relationships it has created. We will perform a forced reset on the language of consumerism that in turn will help us to develop more interesting, involved, interactive, mutually respectful and naturally more beneficial, respectful and rewarding relationships between our organizations, our audiences and finite resources of our world. All pirates undertake to advance the evolution of the idea of ‘the citizen’ as the dominant defining thought of our audiences and communities, and of our future.

INSPIRATION

Founding partners of the New Citizenship Project, Jon Alexander and Irenie Ekkeshis, are both former advertising executives who’ve done their time in the engine room of consumerism and are now pioneering an alternative idea, that it’s time to make the Citizen Shift, where the principles of citizenship replace those of consumerism.

Jon and Irenie are pragmatic, professional and potentially the smart strategic intervention that’s required in an otherwise seemingly insurmountable challenge of the human race eating itself.

The New Citizenship Project presents an optimistic vision that, whilst consumerism had its benefits, if we are to now escape its toxic and limiting relationship with a world of finite and diminishing resources, we need to evolve into citizens. The vision of the New Citizenship Project is that, instead of seeing the term consumer over a thousand times a day (as most of us do), we replace this with the language of citizen, and in doing so reverse the tyranny of the holy trinity of scale, growth and consumption. Or as Jon concludes:

You can start, in your own life and work, by changing your language; and you will discover a whole new world. Thinking of people as consumers, the only ideas you can possibly come up with are for stuff people can buy from you; your brain is building on scaffolding that will allow nothing else. But think of people as citizens, and you must start by asking what the purpose of your organization is, and how you could invite people to participate in that purpose. You will move from ‘us’ and ‘them’ to ‘we’. You’ll start to create the future. And you’ll stop propping up a past that needs to die.2

WARNING

Anything deemed anti-consumerism can have a polarizing effect and there are staunch defenders of the benefits of globalization with good arguments that deserve to be heard and learned from.

Don’t let an idea this important get distracted by that debate; don’t mistake, or let others mistake, the argument for a move to a citizen mindset as anything less than rational case for an evolution, for the next stage in our development and the deepening of our relationships between individuals, organizations and environment.

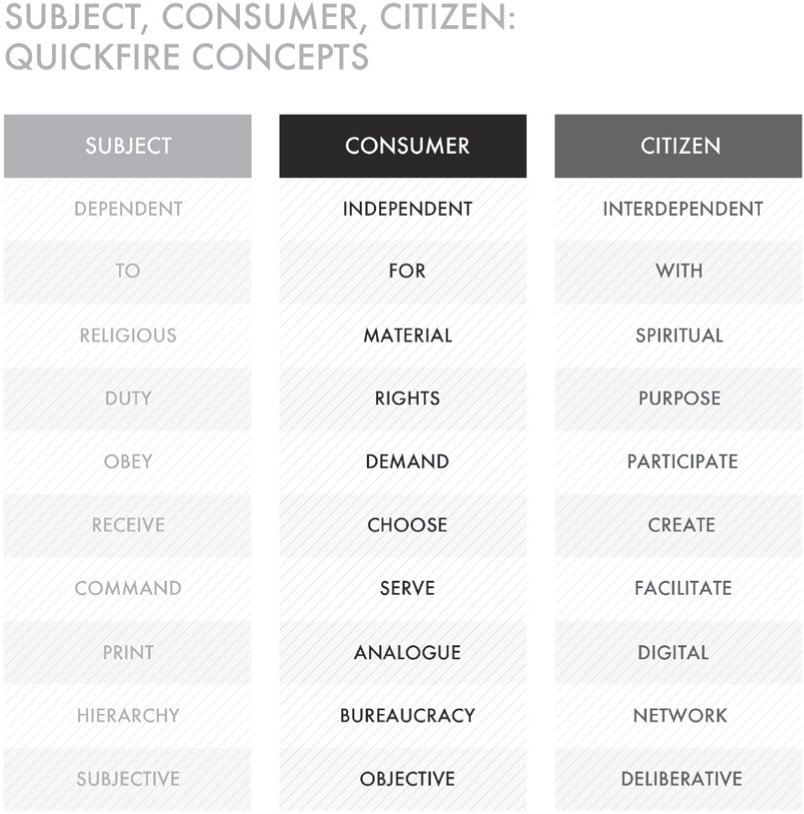

One look at the chart on the previous page, taken from the New Citizenship Project’s report ‘The Citizen Shift’, will help you navigate this evolution.3 It’s a summary of ‘quick fire concepts’ showing the shift from subject to consumer to citizen.

Article 4 – Take Happiness Seriously

THE CHALLENGE

Humanity is experiencing its highest ever-recorded rates of anxiety, depression and suicide. In the UK and US depression is at an all-time high. Over-exposure to social media, relentless bombardment from advertising and media telling us who and how we should be are all endlessly undermining our already fragile self-worth. And yet, whilst we know a servile relationship to technology, brands and consumerism makes us sad, we still wake up, check our phones and follow the call to buy stuff, like stuff and swipe stuff in order to get an ever-reducing hit of endorphins. According to the 2017 global mobile consumer survey, checking social media is the very first thing many of us do every day, even before we get out of bed.4 And this would be at least our own fault if we were only semi-consciously doing it to ourselves; it’s when you look at the sadness we’re systemizing into children’s lives it gets really depressing; for example (and there are many examples to choose from): 50 per cent of five-year-old girls in the US worry about their weight, largely inspired by the 3,000 adverts they see every day according to a programme participated in by Harvard University and led by the author of Killing Us Softly, Jean Kilbourne. ‘Women and girls compare themselves to these images every day,’ Kilbourne said. ‘And failure to live up to them is inevitable because they are based on a flawlessness that doesn’t exist.’5

In addition to the pervasive nature of advertising, the landscape undermining our happiness has been added to and accelerated by technology. The more time children spend chatting on social media, the less happy they feel about their school work, the school they attend, their appearance, their family and their life overall, according to a team of economists at the University of Sheffield.6

Ever since the need for it led to the advent of World Mental Health Day in the nineties, there is at last a more mature global conversation happening about mental health, well-being and happiness, but some of it needs to be treated with caution. Because, ironically, many of the same brands, and sometimes entire industries who made a fortune undermining our self-image are now heavily invested in celebrating our identity. As with any emerging market there’s an app for that, yet for the thousands of well-being apps on the market, according to research published in the journal Evidence Based Mental Health, there is no proof that 85 per cent of the apps accredited by the National Health Service actually work.7 Apps are just the tip of the iceberg and the once outlying well-being industry has come in from hugs and herbal teas to become a sophisticated multibillion-dollar empire of hermetically packaged lifestyle products.

Even now that we can make some money out of it – which, let’s face it, is usually when we begin to consider that something is important – we’re still a long way away from taking happiness as seriously as we should.

SUGGESTED ARTICLE

We take happiness seriously, and give deep happiness the place and importance it deserves. We see happiness as a strategic driver for success, productivity and creative output, but also as a strategic objective in and of itself. We do not believe happiness is a nice-to-have, we believe it is a need-to-have. We make happiness a starting point, not just an end point; we use our intention to achieve happiness to inform the decisions we make, the environments we create and the projects we undertake. We endeavour to measure, manage and share the proof we accumulate that happiness is symbiotic with great work, great impact, great relationships and greater effectiveness. We do not conform to a one-size-fits-all happiness, nor expect to be happy every day, but accept and respect the right to make happiness the goal.

INSPIRATION

There have been several attempts to give happiness the status it deserves. The macroeconomic argument that we should try to measure a country’s Gross Domestic Happiness instead of its Gross Domestic Product was first put forward by the King of Bhutan, who coined the phrase, but whilst popular for a spell with some world leaders, including David ‘Kiss of Death’ Cameron, as an idea it was riven with complexity, and even Bhutan is said to be focusing on more traditional metrics to measure a country’s performance.

A 700-person experiment conducted in 2017 in Britain by the Social Market Foundation and the University of Warwick’s Centre for Competitive Advantage in the Global Economy provided concrete evidence that happier employees are more productive in the workplace. In the experiment, when happiness metrics were increased then productivity increased on average by 12 per cent, and reached as high as 20 per cent. Dr Daniel Sgroi, the author of the experiment, points out that rises of 3 per cent in the comparative GDP are ‘considered very large’.8

The researchers also demonstrated a link between unhappiness and decreased productivity that lasted up to two years.

Dr Sgroi hopes his work will: ‘Help managers to justify work-practices aimed at boosting happiness on productivity grounds,’ because, sadly, we couldn’t justify them on happiness grounds.

On an individual level, an excellent exploration of the topic (and book) is Happiness By Design, by Paul Dolan, a Professor of Behavioural Science at the London School of Economics.9 Dolan does his own research into happiness: how it happens, how it can be measured and how it affects us. He moves the debate on significantly from self-help, pop psychology and mindfulness into a very practical framework as he shows that happiness is not just how you feel, it’s how you act and very much what you do. Being happier means we have to look at what’s around us, from eliminating the things we waste time on to increasing time spent in nature or with good friends.

There are literally thousands more explorations into not just how we find happiness, but how we embed it into our lives, and defend it from being seen as an afterthought, from a multitude of books that range from The Happiness Project and The Architecture of Happiness to The Happiness Advantage, which are all well worth a read. But if you want something more digestible, a search for ‘happy’ at Ted.com will unearth over 500 talks for you, or try SlideShare, where the same search will yield over half a million results.

Clearly, there’s no shortage of inspiration. One opportunity that feels genuinely new is a Massive Open Online Learning Course being run by University of California at Berkeley on The Science of Happiness,10 and claiming to be the first MOOC to teach positive psychology. Learn science-based principles and practices for a happy, meaningful life. The course launches in 2018. I have just signed up.

WARNING

If we are going to get serious about happiness, we also can’t get too simplistic. Emily Esfahani Smith, the author of The Power of Meaning, warns in a TED talk against a one-dimensional understanding of happiness and shows that chasing happiness can actually make people more unhappy.11

She puts forward a different way, based on four pillars – belonging, purpose, transcendence and storytelling – to create a ‘meaningful’ life. Taking sides with the Buddhist ideal that ‘all emotions are useful’, Emily makes the case for a meaningful life, which will ultimately make us ‘happier’ rather than being obsessed about happiness.

Multiple heavyweight research institutes, including Harvard’s Department of Psychology’s longitudinal Study of Adult Development, which followed its subjects for over fifty years, unreservedly agree that relationships are essential, with the happiest (and healthiest) of us being those who cultivated strong relationships with people they trusted to support them.12

But don’t make the mistake of thinking that, because you’ve got more than the average friends on Facebook (200) or followers on Instagram (150), happiness awaits. Think again, because rigorous research conducted in 2017 confirmed that ‘the more you use Facebook, the worse you feel’.13 In the Harvard Business Review article that reported this, the researchers were quoted as saying:

Our results showed that, while real-world social networks were positively associated with overall well-being, the use of Facebook was negatively associated with overall well-being. These results were particularly strong for mental health; most measures of Facebook use in one year predicted a decrease in mental health in a later year. We found consistently that both liking others’ content and clicking links significantly predicted a subsequent reduction in selfreported physical health, mental health, and life satisfaction.

As we can see, striving for happiness isn’t always easy and not all relationships are healthy. We should be aiming for meaning and seeking to strengthen real-life connections, not digital ones, rather than fall into the trap Esfahani Smith identifies that if we’re not careful, then the search for happiness makes us unhappy.

Article 5 – Adopt the New Work Manifesto

CHALLENGE

Workplaces, and work in general, have become bad for us, really very bad for us. (This isn’t an excuse for me to get out of a real job and write books for a living, it’s a fact backed up by hard evidence.) Studies show that the length of the average working day has increased by almost 25 per cent, a not insignificant creep of a few hours at the beginning and end of the day. The reason? Technology, of course! Our emails and other methods of communication are all pinging to our smart-phones, which are by our beds and by our sides at all times. What was once unthinkable (checking messages before getting out of bed, on the toilet or at family lunch) is now ordinary.

But, sadly for us, the increased investment of attention and energy has yielded no positive results, and whilst the time spent working has increased dramatically, productivity hasn’t moved at all. Our overall productivity per hour has dropped. We work more to achieve less, and as a result are more stressed and less able to disconnect from work and reconnect to life. And that’s just messages; we haven’t even begun to talk about meetings! You’re not alone in thinking business meetings as well as emails are, by and large, a waste of time.

There’s an argument that we haven’t mastered the energy-saving technology we’ve invented yet, and that when we do, in a few more years, we’ll look back and laugh at (relative to the tools we have) humankind’s least productive moment in evolution. I don’t know about you, but I’m not thrilled by my long working days being the punchline to some future joke.

But there’s more. Multitasking: turns out it was a lie. Open-plan offices being good for productivity: also a mistake. Those Microsoft adverts that promise we can run a business from the park whilst playing with our kids all from a nifty handheld device: ditto on the bullshit barometer.

For those of you who went to (or attend) university, the way you worked there will be the last time you ever worked sensibly. You agreed an end goal, you had clear quality measurements and an overall deadline, but then how you worked, the hours you kept, the location, devices, tools and techniques for getting the work done – they were all up to you. As soon as we ‘grow up’ we graduate into much less sophisticated and sensible metrics, having always to adhere to someone else’s time, be present and concentrate in countless compulsory meetings and churn out work to meet standards more to do with timing, budgets and egos than our own internal measure of quality or satisfaction in a piece of work well done. This means that, quite apart from all that lack of productivity dragging our organizations down, we miss out on the fulfilling reason we humans need to work in the first place.

SUGGESTED ARTICLE

We want to love work, we want to learn as we work, we want to be proud of what we do and have the chance to do it well. We want work to make us better, not worse, we want the rewards of creativity, friendships, fulfilment and knowledge to match the financial compensation we need. We want life/work balances, not the other way around. We intend to live up to the promise of technology, efficiency and flexibility. We commit to understanding our own inner engineering for effectiveness and refuse to submit to conditions, clocks or cultures that don’t get the best out of us. We will break the tyranny of emails, meetings, to-do lists and any other anachronistic trappings of an old way of working, if they don’t work for us, and we won’t stop until we’re judged on our output, not our input.

INSPIRATION

ROW is what you need to know, aka Results Only Working, the brainchild of two workplace productivity consultants Cali Ressler and Jody Thompson who’ve captured their approach in Why Work Sucks and How to Fix It: The Results-Only Revolution.14 This is a book that everyone who works anywhere needs to read. It explores many ideas that we’ve looked at and argues that fulfilling our desire for self-direction, autonomy and accountability leads to greater productivity. In a ROW, you are the boss of your time, as long as you deliver the results. Hang the emails, screw the meetings and forget about turning up on time. It’s not actually that radical, but based on the evidence they put forward it is potentially revolutionary.

The other great mind that’s changed my own, and the way I work, and in turn led to the suggestion of this being an essential part of any Pirate Code 2.0, is Cal Newport and his book Deep Work.15 It’s Newport who’s suggesting our kids will laugh at us from their super-streamlined energy-efficient futures, working only the hours that matter with technology their slave. But he doesn’t say it like that, he says it with grace and humour and makes the unquestionably solid case that multitasking, open offices and in particular notifications are as much good to a productive morning’s work as polishing off a few glasses of wine, and a lot less fun. As a direct result of learning from Newport, I stopped responding to emails until midday, which, unless there’s an emergency, sounds like a long time, but is a small chunk of the day, and whilst scary to do, immediately became the most productive, and then enjoyable part of it. There’s a reason The Economist called Newport’s book ‘The Killer App of the Knowledge Economy’, and it’s because it works.

If, unironically, you don’t have the time to find out about saving time, that’s OK, because a very nice man called Bruce Daisley has created a podcast called ‘Eat Sleep Work Repeat’, that, in his own words ‘helps answer the question “how can we be happier at work?” ’ As of the end of 2017, it had topped Tim Ferriss on the iTunes Podcast Top Ten, which, considering Tim Ferriss is a God of professional personal development (and the author of the original 4 Hour Week) and Bruce an unassuming newcomer, says a lot about a) the appetite for this conversation, b) the quality of advice and insights on the series and c) what a nice chap Bruce is.16

The New Work Manifesto is an output of the ‘Eat Sleep Work Repeat’ series and provides ‘simple evidence-based ways to improve our jobs’ and a clear starting point for anyone interested in not getting lost down a productivity wormhole and embracing some well-founded new ideas about working smarter.17

WARNING

It is possible to become obsessed with this topic. Graham Allcott, the excellent author and founder of Productivity Ninja, calls it ‘Productivity Porn’. Basically, there is a whole industry promising to save you time but actually fighting for your attention and selling you apps, books and conferences. Watch out you don’t end up spending more energy on your productivity habit than you save elsewhere.

On the whole, productivity is a lot simpler than you think. It’s just about taking a few steps to regain control of your time. When, for so many people, the main culprit for suffocating self-discipline is email, Bruce Daisley in his podcast makes a typically astute observation that, whilst it can seem daunting, when you do push back on technology, and email in particular, it ‘yields far more easily than you think’. So go on, give it a push.

Article 6 – Embrace Diversity to Raise Your Game

THE CHALLENGE

‘Diversity raises the fucking bar,’ said Cindy Gallop, the ex-advertising guru and now founder of IfWeRanTheWorld and MakeLoveNotPorn and one of the most creative, outspoken and brilliant champions of diversity not just being a box-checking exercise. We know intuitively that diversity matters, but what matters more now is that we make it clear diversity isn’t a choice for us to take, it’s a change we have to make. By diversity here we’re referring to the global conversation that’s happening at every level of culture, from the representation of ethnic minorities in Academy Award nominations via the gender pay gap and unbalanced educational achievement through to unconscious bias in recruitment and cultural misappropriation in the media.

According to the 2017 report ‘Why Diversity Matters’, produced by the consultancy group McKinsey,18 the evidence is clear: organizations with an ethnically diverse workforce are up to 35 per cent more likely to outperform their less diverse rivals, and those that are gender diverse achieve up to 16 per cent more than their less diverse competitors. We talk a lot about diversity being the right thing to do, but it’s important that the conversation matures to being about the ‘best’ thing to do, for the organization as well as the individual.

Diversity isn’t just about good practice, it’s about getting to good answers, the ones a complicated world needs. ‘Everyone in a complex system has a slightly different interpretation. The more interpretations we gather, the easier it becomes to gain a sense of the whole,’ said Margaret Wheatley, the organizational behaviourist we learned from earlier.19 It is a cruel irony that in our globalized world cultural integration is a necessity, yet significant swathes of society are so scared of what that means for their original identity that they violently reject inevitable progress. Margaret acknowledges not just the practical need for diversity but also its power when she says, ‘You can’t hate someone whose story you know.’

The conversation is huge, needed, in some instances a little behind the times, and is only going to increase in importance.

But there’s a problem. We already risk burnout, when the conversation isn’t even at a baseline. You see, we’re working back from such a deficit, where industry after society after institution remains structurally in favour of middle-class white men, that we’re in danger of complacency and mistaking improvement for achievement. At worst, ‘diversity’ is at risk of becoming a trend, a campaign or even a return to being a box to tick.

SUGGESTED ARTICLE

We believe diversity of thought, background, experience and understanding is a driver of competitive advantage, creativity and productive cultures. We who desire to create projects, products, content and campaigns for the future, know the importance of reflecting the future we want to see, one of interconnected, collaborative, communicative, creatively colliding cultures. We commit to recruitment that opens doors to more than the usual suspects, we will go the extra mile to find the talent that might not have found us. We commit to accepting we all have prejudices, and then commit to challenging them, along with expanding our own filter bubbles and stretching our unconscious biases to breaking point.

INSPIRATION

In the early 2000s major institutions around the world welcomed the newest senior hire, the arrival of the chief diversity officer. This was a welcome recognition of the need for a focus on diversity at the highest executive level of any organization and trod the path of chief electricity officers in the early twentieth century and the chief technology officers of the late twentieth century. The trouble is, they all start to feel out of date after a time, as the focus they address begins to feel as though it ought to be becoming automatic. The well-intentioned but now anachronistic chief diversity officer is yet another sign that, just as every organization that wanted to survive the information age needed a holistic plan for universally embracing digital technology, so too do we need to do our CDOs out of a job. Luckily, there’s been an upgrade to the idea, and the best current thinking for anyone in any industry comes from the Great British Diversity Experiment, founded by, amongst others, Alex Goat, the CEO at Livity.

The first experiment took place in 2016, curating deliberately diverse teams to tackle major industry challenges in order to prove that the breadth of experience within a team increased its chances of finding viable solutions to intractable problems. Safe to say, it was a stunning success. The GBDE’s full findings are available to all online.20 Whilst they’re pretty frank, the GBDE are the first to say, ‘This is not an exercise in industry-bashing but a tool to confront the elephant in the room.’ And they conclude with several helpful bits of advice for organizations dedicated to creating diverse teams, and three core reasons why diversity makes a positive difference:

- Being in a diverse working group allows people to be their authentic self – being able to be yourself, and not play to type, means you can contribute more creatively and be much more effective in your job.

- It dramatically increases the possibility of new connections between experiences, perspectives, and insights that lead to distinctive, powerful and new creative ideas.

- Diversity means ideas develop via meritocracy, and not quick buy-in from the dominant cultural voice. It forces us to be truthful about creative merit rather than fall prey to cultural consensus.

GBDE is both excellent work in itself and an essential to-do list for any team of any size, but as you work your way through it, there’s one last super-simple and accessible trick for your toolkit, and it’s called Project Implicit, Harvard University’s online implicit bias test.21 It’s a surprise for most people who try it, and usually a useful one, and it’s smart enough to update itself regularly, because the really smart people seeking to overcome their unconscious biases are also using it regularly to measure their progress.

WARNING

The negative effects of a lack of meaningful diversity are self-evident all around the world and across political, social and economic lines. Understandably, increased division brings greater calls to overcome the diversity gap, a call that often is interpreted as a need for greater empathy, i.e. the ability to understand and share someone else’s feelings and experience.

The team at Livity will caution you, because, whilst an admirable ambition, the truth is that making empathy the aim often inadvertently achieves the opposite of increased diversity for the simple reason that human beings are biased and find it much easier to empathize with people who have similar experience sets to their own. We also subconsciously overlook the views of those we don’t feel familiar with. As Emily Goldhill, a senior strategist at Livity, puts it, ‘People’s own echo chambers limit their willingness to engage with the unknown. Sometimes they’re simply unable to see past their own opinions, which prevents an open dialogue from ever taking place. Empathy, rather than breaking down barriers, can, in fact, reinforce them as support is given to those similar to you, leaving only stony indifference for the rest.’22

Don’t be complacent about the limits of empathy, or our ability to be blind to our own biases. None of us is immune and the mistakes we make can be costly. Think of the well-intentioned but ultimately fatally flawed Pepsi campaigns starring Kendall Jenner that started out trying to raise a flag for diversity and ended up a joke, to be parodied for ever more.

Create your code: adoption and adaption

These proposed articles are assembled from some of the best, bravest and most badass minds I consider myself lucky to have come across, from all corners of the earth, all sectors, industries and ages. However, they are all related in that they are from examples of bona fide change-makers, people truly delivering on their promise to make a real difference to their world. They are tried, tested and trustworthy.

I hope you’ve seen some articles you’d like to adopt, some you’d like to adapt, some parts of articles that you like, parts you didn’t and probably a whole article or two you disagree with or know is not for you. And that’s fine. I’ve tried to keep the suggested articles within the style of the original codes, and I’ve tried hard to create ones you might love – but have no sympathy for me: if you hate them, ignore them; write yours and rewrite mine in whatever way that works for you.

The sole aim is to create exciting and inspiring articles, that are simple to understand, easy to agree with and hard to get out of.

So, how do you make a code that smells like victory? Creating your Pirate Code is all about adoption and adaption. Take what you like and change what you don’t. You don’t have to start from scratch, you don’t have to follow anybody else’s rules, you can take some and then bend them, or you can steal them with glee exactly as they are. If they work for you then it’s a clear copy-and-paste, open-and-shut case.

Whilst it doesn’t matter if your code is an act of piracy, what is important is that it’s to the point, memorable, short, concise, snappy, accessible, easy, buyable, usable, uncomplicated and effortless to understand.

You get my drift. It’s essential to keep it simple. A good target for any code is between five and ten articles, with each article being a sentence or two at most. Keep your code easy to follow.

But this does not mean codes are easy to create. They require deep thought, and getting to a consensus is almost always tough, even if there’s only one of you. Be prepared: it’s often harder to get to one clear line that several of you agree on than it is to write a whole page. But this is not like business planning. This is not a process of introspection, this is not supposed to take you away from where you’re supposed to be (in front of clients or customers or being creative) for days on end. This is simple and a way of finding your centre of gravity before the next adventure starts. You’ve got to be ready to live or die by them, so get them right. But, at the same time, don’t panic. New adventure? New crew, new set of articles.

As you prepare to write your own code, please only look for articles that will lift up your heart, your ambitions, your confidence and your energy levels, so that you will feel good using them to create a fulfilling and successful life. As you consider how to be more pirate in and amongst the daily grind of your life, make sure you’re ready to ride the coming waves, always remembering that you can adapt the code for your next adventure based on what you’ve learned from the last. Once you’ve got your code underway, consider how you’ll make it memorable.

Way back in the pirate day, each crew member was expected to make their allegiance to the code clear. The more romantic pirate stories tell of sworn oaths over crossed pistols or swords, or an oath taken with hands held upon a human skull, or even with a pirate sitting astride a cannon. You can take that as literally as you like, depending on how many swords, skulls and cannons you have access to, but many successful modern companies test their latest employee’s allegiance to their code as soon as they’ve joined.

Zappos, the wildly successful online retailer (famed for a culture so valuable it led to the company’s sale in 2009 for $800 million to Amazon), go so far as to offer every new starter at the organization $5,000 to leave. It sounds counter-intuitive at first, but very quickly, and relatively cheaply, they distinguish between the starters who intend to stick around and those with a shorter fuse. There are no crossed pistols, but there’s also no mistaking that, from that moment forward, you’re one of the crew.

What you create as your articles, how you mark the occasion and how you make your articles memorable is all important, but what’s also essential, and the final ingredient necessary to make any code work, is how you make it accountable.

Written in blood

Creating your code and choosing your crew is one thing, making it all stick is another. The final piece is how you hold everyone (even if that’s only one or two of you) accountable for the choices you make and the code you create.

Authentic accountability is the key to lasting success. Holding yourself and your crew accountable to the articles you agree is the difference between pirate legend and pirate loser.

The Golden-Age pirates, having all signed their codes, ensured an air of authentic accountability hung over them by displaying the code in a prominent place, sometimes over the door of the captain’s cabin, sometimes on the mainmast and always somewhere they could quickly be slung overboard, for they’d surely become the pirates’ death warrant in the wrong hands. Always, too, in the spirit of their total democracy, the articles of association that had been agreed by everyone aboard were also watched over by everyone aboard.

Making your Pirate Code accountable is not an exercise in writing your values on the wall and then forgetting them; this is about writing your own code in your own blood in a way that can never be forgotten.

I don’t actually want any of you to write anything in blood, I’m just trying to be dramatic. I want to convey the appropriate sense of importance of the point of pirate accountability, because you really need to focus on this point: the context of accountability and the seriousness with which the code was upheld.

The code was law, transgressions were unacceptable. It was an act of shared creation and commitment and it enabled everyone on the crew to look each other in the eye and know they could trust one another with their life to act in honour of the code. Without mutual and binding consent your code won’t hold its full potential or power.

For a shot of rather bracing inspiration that should definitely be taken with a pinch of salt, let’s look again to the pirates, and one of the articles of Captain John Phillips, which provides an excellent suggestion for motivating consistent behaviour:

If any Man shall steal any Thing in the Company, or game, to the Value of a Piece of Eight, he shall be marooned or shot.

There’s no ambiguity here, no chance of mistake, for the sake of a piece of eight (about $20) there’s an almost zero tolerance default to the harshest of punishments. For a bunch of robbers, rascals and rogues, the regulations were robustly enforced.

These seemingly classic pirate punishments are given more colour in William Kidd’s code, specifically in this article about embezzlement, ensuring absolutely no thievery amongst the thieves:

That if any man shall defraude the company to the value of one piece of eight shall lose his share and be put on shore upon the first inhabited island or other place.

And, finally, the code of Bartholomew Roberts contains further developments on robust responsibility and settling disputes onshore:

If the robbery was only betwixt one another, they contented themselves with slitting the ears and nose of him that was guilty, and set him on shore, not in an uninhabited place, but somewhere, where he was sure to encounter hardships.

Ouch. And not just a marooning, but one with ‘hardships’ and a slit-open bleeding nose and ears. Ouch again.

Just to be clear, neither I nor any of my very nice team at Penguin Random House are suggesting that you actually maroon anyone if they don’t follow your code to the letter. But you do need to consider the question of how you maroon them if you need to. Metaphorically speaking.

And to be even clearer, it’s not about the threat. I am not advocating threat to get the best out of anyone. Quite the opposite. I’ve never known a threat create long-term improvement in performance. It’s a dysfunctional way to manage, and blunt threats are rare in the lexicon of real leaders.

Instead, the accountability that is the glue of the Pirate Code is the shared sense of a team signing up to an outcome they all agree is motivating. And whilst not getting marooned is quite motivating, it’s the collective decision-making that really makes this so powerful. It’s not rules from the top but a group looking each other in the eye and saying, ‘If we let each other down there will be repercussions and we commit to holding each other to that.’

So as you assess your articles, you need to be thinking about these accountability clauses. They can’t be pernicious for their own sake, but they do have to be tough, and something that no one on the crew wants to endure.

During the process of writing this book, I’ve run Pirate Code workshops with entrepreneurs, executives, middle managers and the most senior leaders. I now gratefully receive messages months after the sessions letting me know their code is ‘something I use every day’ and ‘one of the most powerful tools I’ve got at work’. But it also means I get to see what people use as their approach to accountability. Here are some I’ve seen developed that I’ve been informed worked well:

- Whoever shall break the code buys coffee, every morning, for everyone else, for a week.

- Whoever contravenes this code will be paid a week late.

- Whosoever lets down the crew in the upkeep of this code dress up in any outfit that the crew find suitably amusing, and post it to all their social media feeds.

- The one who breaks the code has to take the other one to lunch, anywhere they so choose.

We’ve all read advice about getting more done, watched a talk about secrets to being more super and at some point promised ourselves a new habit of improved efficiency or better time-management, downloaded a different app, been seduced by the promise of a new pad or even begun a colour coding of our to-do list. Yet here we are again, with a million tabs open, in our minds, screens and lives, and most of our attention on the stuff that doesn’t matter.

The problem is, promises you make to yourself are too easy to break. Making promises to a team makes them more difficult to abandon, which is why the code works, because the promise is made as a group, to a group, on simple articles that are easy to sign up to and hard to break.

Which is why, this time, it will be different. This time you won’t be chasing time, you will just be being more pirate. This time, you won’t have a choice to break your promise, because if you break your Pirate Code, you will be marooned. This time you will create a Pirate Code that you will agree to as a crew, and agree it one to another, and every member of that crew will have equal say in holding every other member to account.

Now you’ve got a starting point for your articles, and you’ve got an accountability or marooning clause in mind, so even if your crew is only you, there is no turning back from the code until the mission is complete, the adventure achieved and the prize taken.

Choose your code carefully, because the day is yours to win, and it’s time to seize it, like a pirate.