VI

1

In the books Le Corbusier wrote or authorized about himself, his three-month return to La Chaux-de-Fonds exists solely as the occasion when he diligently took the opportunity to study reinforced concrete. But his self-imposed isolation at age twenty-two in a barn during an especially severe winter was significant in many ways.

This primitive structure Jeanneret rented on Mont Cornu, three kilometers outside of La Chaux-de-Fonds, was dominated by a wooden-shingled roof shaped like an inverted, flattened V. The second-story hayloft and the covering of thick snow on that sloping roof were the main sources of insulation against the biting cold. The warmest place was the kitchen, a windowless room contained by masonry walls in the middle of the barn and heated by a fireplace serviced by the wide central chimney. More than forty years later, Le Corbusier’s exuberant church at Ronchamp was to restate the form of that primitive barn.

With his parents in La Chaux-de-Fonds, 1909. Charles-Edouard’s bohemian appearance, a vestige of his new life in Paris, shocked his parents.

IN APRIL, Jeanneret took off for Germany. His ostensible goal was to learn still more about the technology of reinforced concrete. But once he was in Munich and the sole architect he admired, Theodor Fischer, did not hire him, he focused on Wagner’s operas, the paintings of Rubens and Rembrandt in the Alte Pinakothek, and the hearty cooking at inexpensive bierstuben. When he went to the Neue Pinakothek to see the latest paintings, he spent precisely seven-and-a-half minutes—he recorded the time—and then declared the visit to have been a complete waste. He preferred the force and purposefulness of Baroque architecture to the stylization and autobiographical content he disdained in more recent artistic trends.

Jeanneret also crystallized his views on Germans in general. He admired the German people for their organizational instinct and deductive reasoning, but thought that they lacked imagination and creative genius. While the Germans credited themselves with having launched a new aesthetic movement, Jeanneret was convinced that their sole achievement was the discovery of Latin genius; for him, they were subordinate to the French, who reigned supreme in the realm of art.

Shortly after arriving in Munich, Jeanneret met, on L’Eplattenier’s recommendation, the man who was to affect him above all others. William Ritter, a music critic from Neuchâtel, was immersed in the work of Anton Bruckner, Leoš Janácek, Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, and Bruno Walter, all of whom he knew. Ritter was forty-two and undisguisedly homosexual in an era when to be so open was unusual. Since 1903, he had been sharing his life with Janko Czadra and would do so until Czadra’s death in 1927. Ritter’s intensity and artistic passion, and his personal courage, made him a hero to his fellow escapee from French-speaking Switzerland. For years to come, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret bared his soul to this father figure who provided him with unequaled emotional companionship.

For now, however, the traveler’s letters were to his mother and father. “The first thing to regret is the exaggerated flight of time,” he wrote them shortly after arriving in the Bavarian capital. “The same old song. Too much to deal with, turning every which way in order to have time to realize that it’s already ten at night.”1 Georges and Marie Jeanneret, on the other hand, felt that Edouard was wasting the time he deemed so precious when, after more than a month, he still did not have a job.

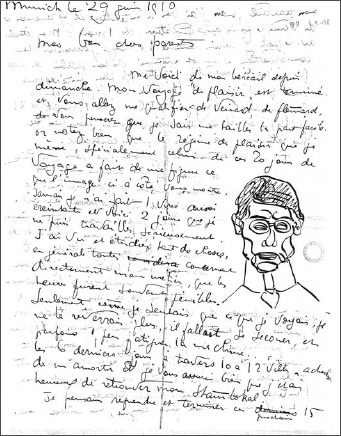

Portrait of William Ritter by Charles-Edouard Jeanneret

Edouard replied to their admonitions with the rudeness and self-righteousness he never lost. “My dear parents, You’re absolutely right to ask for clearer details, but you’re not going to get them! Which is called the rebellion against proper authorities…. Yet I want you to know that my mystery is utterly chaste and my silence merely one virtue added to many others. This silence of mine is the sign of a modest, prudent spirit which regards things according to their causes and their consequences, having sounded the mysteries of human psychology.”2

Even as he feigned control, Jeanneret continued with senseless allegories and a strained humor that bordered on hallucinatory. “Yet I hear the voice of the race, while liable like Icarus to break my neck tripping over a wire; I should like to raise you to the level of my conceptions, but let us postpone such elevation to my next, in order to avoid a flood of amphigoric terms. Speaking positively: did you know that everything depends on elegance here and that I am actually studying the cut of the frock coat I must wear! The bohemian-student type is discountenanced here. One must dress up. And all modern artistic Munich hoists the flag of elegance. And since I am trying at all costs to penetrate this milieu, I too must be gorgeous. At what cost? I who am a monster by nature! O Divinities of India, so plump, so opulent, yield something of your style to the poor admiring wretch who loves your bellies and your smiles…. And to hell with that pianist downstairs in absolute Nirvana! Divinities of India, plenitude inscribed in stone, hear my prayer, and even if you need to summon Bacchus himself, do your work!”3

With style and wine, he might have women.

2

Two months after Jeanneret arrived in Munich, L’Eplattenier wrote with news that turned his life around. L’Ecole d’Art of La Chaux-de-Fonds had awarded him a grant to write a report on the applied arts and architecture in Germany, so that his findings could be applied in Switzerland. It was the first time that the future Le Corbusier was asked to offer expertise on the aesthetic and technical aspects of design and its connection to human experience. He traveled to Frankfurt, Düsseldorf, Dresden, Weimar, and Hamburg, visiting the latest factories, office buildings, and design studios. A modest pamphlet—Study of a Decorative Arts Movement in Germany— resulted.4

He then wrote an essay called “The Building of Cities.”5 In it, he extolled the merits of curved streets of varying width and incline. One should, Jeanneret proposed, imagine the donkey as one’s guide, ambling through urban space with unexpected twists and turns. Jeanneret fastened on to the diversity of old towns that invited circuitous wandering and provided the thrill of variety. The places he enjoyed and the urbanism he now advocated complemented the leaps and wanderings of his soul.

Jeanneret pointed out that, by contrast, in a plan based on a grid—a large square subdivided into smaller squares—the only way to walk from diagonally opposite corners is by following a ridiculous zigzag path. He mocked such orderly layouts and the unimaginative bureaucrats who imposed them on people. La Chaux-de-Fonds, of course, was built on such a stifling concept, with no relationship to the life and vitality of the larger universe and no sense of progression or hope. Fortunately, Milan and Pisa had introduced Jeanneret to the marvelous variability that occurs where every small street stemming from a piazza leads to a different adventure.

As he wrote “The Building of Cities,” the zealot came alive. Eventually, he refined its ideas in his 1924 book Urbanism (also translated as The City of To-morrow).6 For the rest of his life, he espoused these ideals, by which he hoped to give millions of people lives full of diversion as well as calm.

3

In mid-October, Jeanneret traveled to Berlin to attempt to work for the architect Peter Behrens. Nineteen years his senior, Behrens was well established as a designer for German industry. He had developed a streamlined functionalism that was a radical break from all past architectural traditions. Behrens had just finished his renowned AEG Turbine factory, a powerful exaltation of machined forms. His name topped the list of architects Jeanneret admired.

Behrens denied him an interview. The twenty-three-year-old fell into a downtrodden state that echoed his humor in Vienna three years earlier: “Berlin has not conquered me; once you leave the grand boulevards, everything is horror and filth…. Exploring the museums disgusts me in advance. My moods have taken a pathological turn. Yesterday I visited the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, and I can assure you the experience was anything but gay.”7

To his new friend William Ritter, who believed that cities had their own personalities and exercised a powerful effect on their inhabitants, Jeanneret reported that the German capital induced “a feeling of the blackest desolation. Even London could not show me a great city under so monstrous an aspect.”8 But the possibility of working with Peter Behrens justified staying, and Jeanneret was so persistent that he wormed his way into his hero’s office and landed a job. Ten days into it, Jeanneret described his forty-two-year-old boss to his parents: “A colossus of daunting stature. A terrible autocrat, a regime of terrorism. Brutality on parade. All in all, a type. Whom I admire, moreover. My masochism thrills at taking the bit between my teeth when the horseman has such style.”9

Jeanneret was eager that his parents know him as he knew himself: “I must confess that my anxious soul is increasingly tormented. The goal is terrible. Why have I placed it so high? What devil has placed it so far from my myopic eyes? Everything conspires to destroy serenity: lowest details and the highest ideals…. Doubt is a horror. The further I advance, the higher IT rises. Doubts, Stumbles, Hesitations, painful Shocks.”10

As a draftsman for Behrens, he was broke, depending on his commissions from the work at home to pay the twenty-eight marks per month—heat and dinner included—for the room he had rented. “The boss doesn’t pay; it’s all a huge exploitation. The salaries are ridiculous.”11 But at least he was directly exposed to the making of architecture that was unprecedented in its blend of brave simplicity and visual charm. He wrote L’Eplattenier, “Behrens, a severe master, demands rhythm and subtle relations and many other things previously unknown to me.”12

Jeanneret worked from 8:20 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. and from 2:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m.—with Saturday afternoons and Sundays free. Soon he began to receive two hundred marks per month—a pittance, but sufficient to change his housing. He was delighted to move from an overstuffed room whose comforts were anathema to his taste to an austere but blissfully isolated garret. He wrote his parents: “I am…abandoning my huge bedroom for an attic, my armchairs for kitchen stools, pier glasses for a tiny shaving mirror, and racket for peace. There we are. Besides, the slate roofs of Paris are inscribed in my memories, and an attic is much more poetic than too many armchairs, glistening armoires, objects of the most deadening banality which yours truly cannot endure more than a fortnight.”13 One’s surroundings and one’s inner state were inseparable.

4

On December 2, 1910, Jeanneret wrote his parents a poignant letter that obliquely indicated a sexual dysfunction and his general sense of impotence. He began by quoting one of his happy-go-lucky friends from La Chaux-de-Fonds: “Octave Matthey wrote me this week: ‘Since you’ve fulfilled all the requirements for fucking off in less than no time, why don’t you just fuck off. You know you’ll never do anything else as long as you live—it would take such an effort you’d never manage it, even if you died trying. Try it and see!’ Octave’s irony; he knows my sickness and laughs at it. As for me, what sickens me most is not being able to get well. Each day begins by opening a big hole in front of me and dropping me into it because I thought I wasn’t being an idiot, which I am, and in a way that’s disgustingly and unacceptably unfair. Of course it’s my own fault, but my sickness is right there, mocking me, frustrating me. You no longer understand such a creature, my dear parents, nor do I. I’ve given up—first victory, or already a first defeat: trying to analyse why. It’s all summed up in a single word of two syllables: Boredom.”14

Self-portrait in a letter to his parents, June 29, 1910

Disillusioned over his new job, he also poured out his thoughts to the receptive, warmhearted Ritter, in the first of many twelve-page letters in which Jeanneret’s fountain-pen scrawl reached all four corners of the sheet in a stream of associations: “The work I’m required to perform leaves me indifferent. I now judge quite severely a man who has allowed himself to be surrounded by the fatal cortege of fame; though a powerful personality, Behrens has become a victim of his successes. Eager to make money, he undertakes too many projects, losing all effective control over what we, his twenty nègres, often produce reluctantly, merely obedient to an authoritarian and unjust rod. I’m so fond of Behrens as a person and as a man that in order to preserve my admiration, I’ve decided he must be sick.”15

Having initially felt warm toward his office mates, Jeanneret had become contemptuous: “My colleagues are, in every sense of the word, what last Sunday, when I was at home, you feared I might become: superficial architects with no artistic fiber, no passions but the extremely vulgar ones of drink, dancehalls, and an occasionally disorderly life.” Struck by his employer’s instability—“Behrens is a sick man and consequently intractable, unapproachable, immersed in his rebarbative ill humor”—Jeanneret was creating his concept of the ideal architect: “An architect, as I envisage him, must be above all a thinker. His art, consisting of abstract relationships which he cannot describe or depict except symbolically—his art does not require a cunning hand. Indeed, such a hand could be fatal. But this manipulator of rhythms must possess a fully developed brain of extreme flexibility.”16

Shortly thereafter, he wrote his parents about hearing a Tchaikovsky overture remarkable for “the slow, panting, anguished release of the orgiastic orgasm of liberation painted in all the colors of experience and seen as such by the homosexual martyr Tchaikovsky.”17 In his own responses, Jeanneret himself possessed the mental suppleness he craved in others.

5

Soon his state of mind devolved into a “crisis of profound boredom” even more extreme than his depression in Vienna. In his despair, he asked Ritter, “What accounts for this terrible disenchantment? I’m searching my soul to find out.”18 But the ultimate sources of his misery eluded him; something far worse was going on during that Berlin winter than his lack of friends or Behrens’s gruffness. He had lost all hope of pleasure or serenity in life.

To his new confidant, he obsessed about his anhedonic state: “Aesthetic joy is over and done with. Since I’ve been here, I haven’t heard one note of music. So tight is our regimen that it is impossible to attend a concert with any pleasure. It would be exhausting.”19 His absorption with his own misery made him overlook the performance where he had heard the Tchaikovsky overture. “I’m ashamed that once my lucky star guided me to you, all I’ve had to show you was an exhausted, mentally debilitated being,” he wrote. “Never, believe me, have I lived through such a lamentable period. It’s a mistake to blame external phenomena. They’re not all that unfavorable. Here’s another aphorism that I picked up somewhere: ‘All young men, after great enthusiasm, go through a period of depression.’ Perhaps the aphorism itself has done the mischief? You with your profound experience of artists’ lives could enlighten me; berate me mercilessly, or else tell me the cure.”20

He loathed his own appearance, linking it with his unfulfilled craving for women. “Good God! Yet I could, if I really wanted to, eventually consider some young lady ‘inexpressibly lovely’! Hear me out: in my entire life as a student, I cohabited with cats, always above the gutter and never below it. The window was usually no more than a peephole. And when, in the shadows, the mirror afforded a reflection, it would be tiny, wavering, affording my imagination ‘infinite spaces.’ O Prussian inhospitality! My bedroom—I moved out two weeks ago—was a huge monstrosity, two windows took up one wall, and there was even, in the corner, an enormous pier glass, maybe six feet tall and two feet wide. The light came in from the opposite side, and I saw everything in that mirror; I couldn’t believe it, but I went on looking: I saw rickety legs and huge red dangling paws, swollen with disenchantment; a nose straight on which seemed to define the creature underneath, a wrinkled forehead, a crestfallen coiffure and a lot of skin and bones. An unhealthy complexion. The Sunday clothes—the same moreover as those of everyday—were ill fitting. I saw everything; I told you there were two big windows on the opposite wall which showed everything. There was no getting away from it.”21

While he believed that no beautiful woman could possibly find him appealing, he perpetually imagined meeting one. “You’ll understand that I’d be moved to see the inexpressively lovely young lady!” he wrote, including Ritter’s partner, Czadra, in closing, “Some happy day I hope to make tangible my respectful admiration and my gratitude to you both. Yours devotedly, dear gentlemen.”22

6

At the beginning of 1911, Jeanneret’s gloom turned to fury: “With Behrens there’s no such thing as pure architecture. It’s all facade. Constructive heresies abound. No such thing as modern architecture. Perhaps this is a better solution—better than the anything-but-classical lucubrations of the Perret brothers. They had the advantage of experimenting with new materials. Behrens, on the other hand, opposes all this, so with him I’m learning absolutely nothing but facade in everything. The milieu is hateful, my life here is hateful, my life here is idiotic. Exhausting work all day and no reaction possible by night. The better I get to know these people, the emptier they seem. No friend possible except Zimmermann, whose artistic soul is inadequate. No contact, ever, with Behrens.”23

Again, music saved him: “The Jacques-Dalcroze orchestra, virtually the antithesis of that of Richard Strauss, offers me an atmosphere of joy and health spangled with whims and impossible choices, a heaven of gold like those smooth skies of Duccio or the serenely inimitable vistas of Perugino—but resting on a faraway horizon, solemn and sometimes tragic.”24

Everything was reduced to the battle between Latin and Germanic cultures. Strauss, he believed, suffered from uncontrolled hysteria. Similarly, “in Germany, painting and sculpture, virtually the sole metaphysical exteriorizations of our period, are stupid and always backward,” he wrote to L’Eplattenier.25 To Ritter, he lamented, “German painting has stubby wings—how clumsy it looks compared to the French school.”26 The entire German nation, he subsequently harped to L’Eplattenier, was blinded by its unwarranted “artistic pride.”27 Other German-speaking places were just as bad: Austria had been a desert, Switzerland a bastion of poor design.

If only he could head back to Italy and even farther—to Greece, the cradle of ancient civilization! Jeanneret began to hatch a plan.

7

He was thinking about love as much as art. To his homosexual confidant, Jeanneret revealed his amorous musings: “I stole a kiss the other evening from a young lady; today a cat I was holding in my arms disturbed me with its glowing eyes; and this evening in the woods, under the pink sky of twilight, I stood for a long time watching a blackbird singing its heart out; incontestably he was doing his best, he wanted his song to be beautiful; and since he was alone at the edge of the woods, I wondered why he was pouring out his heart so passionately!”28

The gloom of winter was giving way to manic enthusiasm; Jeanneret was ready to blossom. “My spring will soon be coming into its own,” he wrote. “Summer will be here all too soon. After four years of absence, they’re calling for me at home. Now I feel ready to open myself to everything. The period of deliberate concentration is past! Open the floodgates! Let everything rush out, let everything live within!”29

He had decided to embark on a long trip with Auguste Klipstein, a friend he had met in Munich. With no timetable, no fixed destinations, and no names to call upon, they would go to unknown Balkan villages, the great cities of eastern Europe, Greece, and maybe Egypt. Again, his father disapproved, and L’Eplattenier told him he was not sufficiently mature to profit from the trip and that it was a waste. But Jeanneret, excited because Klipstein was “a boy who knows how to have a life even while he’s working away with great deliberation,” was soaring out of his gloom. “I’m making my escape after five months of penitence; gray hours, interminable weeks, leaden months,” he informed Ritter. The trees were budding, a concert of birds emanating from their branches. “Spring is approaching and with it the sun, blossoming, expanding! I feel joy again, the monotonous gray is disappearing.”30

He was imagining naked women “in broad daylight,” the joys of a blue sky and the Aegean.31 He could picture classical architecture with its vertical columns and entablatures parallel to the line of the sea. After the trip, he would settle down to a productive life, but first Jeanneret planned to educate himself in pleasure.