VIII

1

Following Constantinople, Jeanneret and Klipstein headed to Mount Athos. Known also as “The Garden of the Virgin Mary and the Holy Mountain,” this self-governing state inhabited exclusively by monks has been a religious retreat for more than ten centuries. Jeanneret had long been determined to be one of the rare laypeople to visit the sacred territory. Athos is dotted with twenty monasteries, extraordinary in both their architecture and their isolation, and he counted on expanding on the fantastic experience he had at Ema.

Entry to Athos, however, was an arduous affair. The instinct and tenacity to make this pilgrimage to the Holy Republic distinguished Jeanneret and Klipstein from virtually everyone else they knew. Few of their contemporaries raised in the stronghold of Protestantism would have dreamed of hazarding the trip to the territory of total maleness, religious devotion, and physical isolation; even drinking the thick foreign coffee that coats the teeth with bittersweet muddy powder, a staple of this journey into the Turkish empire, would have been unthinkable.

In Constantinople, Jeanneret had had to obtain a letter from the Greek patriarch, which necessitated a recommendation from an embassy. There was, however, no Swiss embassy there. He had had to turn to the French authorities, who were not inclined to help someone who wasn’t one of their citizens. Armed with letters from L’Eplattenier and Perret, he asserted himself until, finally, after several weeks, entry documents in hand, he was on his way.

MOUNT ATHOS IS one of three peninsulas in Macedonia in northern Greece that stretch down into the brilliant blues of the Aegean Sea. The most easterly, it has the form of a splayed claw. Its jagged mountain peaks, treeless and rocky, are virtually inaccessible, although Lord Byron claimed to have scaled the bare summit, 2,030 meters high, and to have seen the plains of Troy from it.

On the fertile cliff-top plateaus near the sea, large monasteries were built starting in the eleventh century. The pine forests around secluded coves lined by sandy beaches were scattered with dwellings for smaller groups of monks who preferred even greater isolation, as well as with huts for monks requiring solitude.

The monastic republic is accessible only by sea. Jeanneret and Klipstein first had to travel on rugged roads for many hours from Thessaloniki southeast to the port of Ouranapolis to get their boat. To their surprise, rather than sail directly to Athos’s entry port of Daphni, they first were forced to take a small dinghy to a desert island just offshore from their departure point. There they spent four miserable days quarantined in a cell that Jeanneret compared to a cage for chickens and where his and Klipstein’s underwear was taken so it could be boiled. Finally, they were released and boarded a large boat for the three-day crossing.

But the moment Jeanneret stepped off the boat at Daphni on August 24, he was transported. The town was inauspicious—a cluster of a few ramshackle wooden structures for customs officers—but Jeanneret was captivated by the landscape, which struck him as sacred. The grandeur and majesty of the mountain in front of him was more impressive than any man-made construction he had ever seen. And he exulted in the myth of this bold pyramid form shooting up from the sea—said to have been the rock that Athos, the leader of the Giants, had cast at his foe Poseidon, the leader of the Olympians, but that had missed him and fallen into the ocean.

In early Christianity, a tradition developed that Athos was holy ground and had been visited by the Virgin Mary. The mountain was dedicated to the Mother of God and her glory, so other females were not permitted there. Edith Wharton had written in 1888 when she peered at the sights of Athos from a deck without being allowed to land, “The early established rule that no female human or animal, is to set foot on the promontory, is maintained as strictly as ever; and as hens fall under this ban, the eggs for the monastic tables have to be brought all the way from Lemnos.”1 The idea of this haven conscribed exclusively to the Holy Mother impressed itself on the traveler who four decades later designed his chapel at Ronchamp, dedicated to this same Marie.

2

For about two weeks, Jeanneret and Klipstein traveled by mule and stayed in various monasteries. The high-perched building complexes were unlike anything Jeanneret had ever seen. So was the endless horizon, devoid even of boats. Sleeping on cots in the spare rooms, savoring those vistas of sea and sky, dining with monks in the refectories, Jeanneret felt his life change.

He wrote of the trip to Athos, “To go there requires physical courage not to doze off in the slow narcosis of so-called prayer but to embark, rather, upon the immense vocation of a Trappist—the silence, the almost superhuman struggle with oneself, to be able to embrace death with an ancient smile!” The sea journey itself provided a new sense of what mattered in life: “Lying motionless at night, I feigned sleep, so that I could gaze, with eyes wide open, at the stars and listen, with ears fully cocked, for every trace of life to subside, savoring silence in its glory. These were the happiest hours I have ever experienced.”2

The obsession with the horizon that Jeanneret developed on Athos was to determine the way he positioned almost all of his subsequent architecture. The smooth and continuous line where sea and sky meet had a meaning well beyond its visual beauty. “I think that the flatness of the horizon, particularly at noon when it imposes its uniformity on everything about it, provides for each one of us a measure of the most humanly possible perception of the absolute,” he wrote.3 In his future, there were to be other forms of horizon: the bumpy juxtaposition of gentle fields and sky as seen from the terraces of the Villa Savoye; the wavy border of the earth appearing like a mirage in the blazing Indian sunlight at Chandigarh. But whatever the base, the boundary between earth or sea and the infinite cosmos of the sky became the focal points of the vistas that Le Corbusier made essential components of his buildings.

The pure and honest architecture on Mount Athos conquered Jeanneret as much as the cosmic setting did. The monasteries built there nearly a millennium earlier as self-sufficient villages eventually spawned his all-inclusive apartment complexes; the stone and plaster constructions where religious contemplation was the goal were reborn in concrete and steel in his monastery of La Tourette.

Immediately recognizing the impact of those monasteries, he wrote in his journal of his “yearning for a language limited to only a few words.”4 In this anonymous architecture, built modestly and purposefully, he saw both the salient honesty and the celebration of life’s wonders that were to be the goals of his own architecture.

Jeanneret found the heat oppressive, yet the sun’s warmth, which served to remind him of its actual fire, also excited him. This landscape with olives and lemons and almonds growing in profusion, with the sea nearby for long swims, became his ideal setting to live in, especially when it offered a view to the infinite.

3

In Journey to the East, an account of this trip published many years later, Le Corbusier mused erotically about his time on Mount Athos: “The night was conducive to any emotional contemplation made languid by the warm, moist air, saturated with sea salt, honey, and fruit; it was also conducive, beneath the suspended, protective pergola, to the fulfillment of kisses, to wine-filled and amorous raptures.”5 What did he mean by these ambiguous remarks about the all-male domain? Was this a memory or a fantasy? Was he revealing a homosexual encounter on the spot where Lord Byron had trod a century earlier? Or was he insisting that abstinence, psychologically, was impossible, that the territory set aside for men to be celibate had the opposite effect and filled the mind with the longing for a woman?

Le Corbusier was deliberately obfuscatory. At that time, he lacked a clear direction and lived mainly in his head. But he observed richly and imagined mightily, especially when describing his thoughts in Karies, a village in the hills in the middle of the peninsula. Full of hazelnut trees, Karies had been established as the capital of Mount Athos in the tenth century. Jeanneret wrote: “With the overwhelming heat of the evening and our sudden transplantation into the sensuous night of such a place, a more than Pompeii-like feeling resonates with a heavy languor, and the loneliness of my heart conjures, in this glowing warmth, the black outfit and dismal figure of a marquis standing away from the group, far from the tables beneath the lattices and vine leaves, and leaning against the railing, back turned, lost in the contemplation of the sea. No, for more than a thousand years, this very simple and unique inn in Karies had lodged neither a marquise nor a courtesan, not even a simple woman traveler. For this land with the most Dionysian of suns and the most elegiac of nights is dedicated only to the dejected, the poor, or the distressed, only to the noble souls of Trappists, only to criminals fleeing the laws of men or sluggards fleeing work, only to dreamers and seekers of ecstasy and solitude.”6 That his reverie was simultaneously so vivid and so ambiguous was both a gift and a burden to the young man trying to forge his identity.

4

Jeanneret and Klipstein decided to approach some hermits living in sketes— the dry stone huts that provided maximum isolation. The recluses responded to their greetings by offering large bunches of grapes, which the visitor from Switzerland considered symbolic of both human generosity and the earth’s bounty.

Of the monasteries, Lavras, which had been founded in 963, impressed Jeanneret especially. Its design has an abiding simplicity and derives from the purpose of providing proximity to nature in a tranquil setting. As one approaches the rambling structure from the sea, its rows of bedrooms look like white linen hanging on a laundry line in the wind. The top stories are perched on skeletal structures that project them in the direction of the horizon. Inside, the plain white walls are clean and silent. All of these elements reappear in Le Corbusier’s luxurious villas and large apartment buildings, while other details—the large bell next to the chapel, the minimal Christian crosses, and the outdoor places of worship—all show up at Ronchamp.

The monastery’s refectory was to have an equal influence on Jeanneret’s work. It is an extraordinary salubrious space for human congregation; the overall impression is of rough plaster—painted with a marvelous bright whitewash—and then of the subtly colored frescoes that cover many of the walls and convey a biblical narrative cogently and gracefully. The tables in the refectory are semicircular, thick, coarse slabs of marble, quarried on islands in the Marmara Sea and, like Carrara marble, dominantly white with grayish-blue veins.

These slabs and the benches that accompany them ennoble the act of eating and sitting. The wooden seats are long planks set into whitewashed plaster bases that echo the curves of the tables. Le Corbusier made similar custom-fitted furniture in the lakeside villa for his mother, in his own cabanon in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, and in other residences. Like the anonymous architects of Lavras, he, too, unified functional, dignified furniture with luminous architecture and colorful art so that all the elements work in tandem.

Jeanneret reveled in the ambient honesty and strength of these surroundings and the monks who inhabited them: “We sit down on the white wooden benches. The monks’ hands are rough and calloused, swollen from working the fields, and their robustness is at one with the plates and enameled earthenware common to the country and implying the soil. Beyond each guest are three earthen bowls containing raw tomatoes, boiled beans, and fish, nothing else. And in front of him is a wine pitcher and a tin goblet, together with round, heavy black rye bread, the daily treasure, the meritorious symbol. In front of the apse, the superiors break the bread, eat their food and drink their wine from the earthen dishes and the green jugs on the unvarnished wood boards, and nothing more. A joyous atmosphere.”7 This became his ideal: earthy materials, lack of pretension, the interplay of work and simple pleasure—all nourished by the southern sun.

5

On Athos, Jeanneret was also awakened to the relationship of a garden to the life it supports. The terrain cultivated for melons and peppers and other fruits and vegetables at the monasteries in time led to the well-planned courtyards and terraces in Le Corbusier’s villas and to the parks he designated for the outskirts of large cities. The necessity of a growing space in communion with a living space seized his consciousness forever.

But while he retained the memory of the pink Judas-tree blossoms and the profusion of delicious sun-gorged vegetables of the Holy Republic, the reality of his time there was less than perfect. In a letter to Ritter, he blamed the monks of Iviron for the food poisoning from which he suffered shortly after arriving there: “Endless diarrhea due to those dear monks whose culinary preparations had wandered into forgotten cupboards.”8 Suffering from at least two intestinal attacks on Mount Athos, he was extremely sick for ten of his days there.

Jeanneret treated the illness with retsina, of which he drank great quantities at night. He marveled at the curative effects and credited the rough wine with his ability to spend the days on muleback ascending and descending the island’s steep hills. This was how Jeanneret found a rather ordinary building that staggered him with the clarity and grace of its architecture. It was a simple, small Byzantine church in the monastery of Rossikon: “Two things: the straightness of the nave, like an immense forum, and then the hollow onion bulb of the dome proclaim the miracle—the masterpiece—of man.” This modest structure had none of the scale of Hagia Sophia or other famous buildings, but it was a kernel of truth. “This architecture, however diminished in volume, commands my admiration,” he wrote, “and I spend hours deciphering its firm and dogmatic language.”9

Undeterred by his ill health, Jeanneret “felt quite strongly that the singular and noble task of the architect is to open the soul to poetic realms, by using materials with integrity so as to make them useful.”10 This church at Rossikon enabled him to recognize the inestimable value of building with a clear conception and a worthy purpose. Jeanneret’s travels convinced him that the standards and integrity essential to such a creation were practically extinct; he would revitalize them: “The hours spent in those silent sanctuaries inspired in me a youthful courage and the true desire to become an honourable builder.”11 He was, for the rest of his life, to strive for this same marvelous combination—logic and directness in tandem with the inexplicable—that he discovered on Mount Athos.

6

Leaving Mount Athos, Jeanneret remained “haunted by a dream, a yearning, a madness.”12 His goal was to see the Acropolis.

On the voyage, for the first time ever, he immersed himself nude in the ocean. He could not yet swim. But, surrounded by water, entirely alone, he felt himself gloriously connected to the larger world. He wrote Ritter, “I look up and it’s splendid. I was plunging naked just now in these classical waters. I have a notion that there was fighting here once. Eleusis is across the away—a few thousand yards. And now, cobalt has filled the folds of the mountains and the beach rising out of the sea. Eleusis? The site of mysteries so long ago! I’ve seen Olympus, first the Asian one, and then two days ago the real one where Jupiter and company were enthroned. A fine mountain with a lovely profile I neglected to mention. Lord! I’ve seen Lemnos and Pharos days on end without flinching, all very beautiful.”13

The man who was so intoxicated by the ancient world and had just bathed naked was thinking more and more about sex. He revealed to Ritter that he was acquiring a very specific taste for large, full-bodied females with enormous breasts—the same creatures who were to dominate his paintings toward the end of his life. He saw the prototypes of these voluptuous earth goddesses on the island of St. Giorgio, near the port of Antiparos, when his boat stopped there on the way from Mount Athos to Athens. The twenty-three-year-old wrote his mentor in Munich, “Back to my old crones, or rather forward to two enormous Greek women who came down to the beach one evening, surrounded by a thick cloud of patchouli, which I greedily inhaled. Lord what women! Splendid animals. I told everyone the identical creatures were to be seen in the two caryatids at the treasury of Delphi. They sat down at a table and proceeded to stuff themselves like the peasants they were, working their jaws to great effect. What arms, what heavy round chins, and what adorable breasts!”14

Sketch showing a view of the Acropolis, September 1911

In the bazaar, he purchased, for one hundred sous, an archaic earthenware figure with a full-bodied form that he likened to Aristide Maillol’s work. On top of the Persian miniatures and the bronzes he had already bought and shipped home, the purchase left him penniless but overjoyed. Clutching it, he wrapped himself in a brightly colored Romanian rug he had acquired on the trip and slept on the deck as the ship made its way toward the Greek mainland. He ate octopus from Mycenae and drank Sicilian wine, which was stored in a cask. In a language he scarcely spoke, he raved about both to the cook.

Then, from the sea, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had his first glimpse of the Acropolis. As light conditions changed before his eyes, he marveled at the overall order evident in the assemblage of temples: “For all the majesty of the natural surroundings, the focal point was an amalgam of buildings perfectly placed on their sites by human beings.”

Toward the end of his life, Le Corbusier acknowledged the indelible effect of both the ocean and the ancient temple ruins at that moment: “Over the years I have become a man of the world, crossing continents as if they were fields. I have only one deep attachment: the Mediterranean. I am Mediterranean Man, in the strongest sense of the term. O Inland Sea! queen of forms and of light. Light and space. The essential moment came for me at Athens in 1910 [sic]. Decisive light. Decisive volume: the Acropolis. My first picture, painted in 1918, was of the Acropolis. My Unité d’Habitation in Marseille? Merely the extension. In all things I feel myself to be Mediterranean: My sources, my diversions, they too must be found in the sea I have never ceased loving. Mountains I was doubtless repelled by in my youth—my father was too fond of them. They were always present. Heavy, stifling. And how monotonous! The sea is movement, endless horizon.”15

Resting on a column of the Parthenon, September 1911

ONCE HE AND KLIPSTEIN got to Athens, Jeanneret postponed the experience of actually walking up to the Acropolis. Even after he resolved to do so, he put it off again to forestall what he knew would be overwhelming. He told Klipstein that he must make this journey alone; he was in too excited a state to be accompanied or let anyone else determine his pace.16

On the designated day, after being on edge all morning, he decided at midday to wait until the sun had gone down. He wanted the effects of moonlight and the solitude of night to be present before going closer to the ancient temple. He calculated that afterward, once he had walked back down to the city, he would have only to go to sleep.

Jeanneret felt overcome by “the deliberate skepticism of someone who inevitably expects the most bitter disillusion.”17 But when he finally reached the Parthenon, the building’s scale stupefied him, and he was exhilarated beyond all expectations. After climbing the steps he considered too large, he walked into the temple on its axis. He looked back between the fluted columns to see the vast sea and the mountains of the Peloponnesus spread before him in the changing light of dusk. Conscious of standing in a place once reserved for gods or priests, feeling himself thrust into an era two thousand years previous, Jeanneret was “stunned and shaken” by the “harsh poetry.”18 In that delirious state, he began to walk around.

ANYONE WHO HAS looked over one of the perfectly scaled parapets on the terraces at the Villa Savoye, who has stood on the roof of l’Unité d’Habitation in Marseille and taken in the mountains to the north and the sea to the south, who has felt the merging of garden and house at the Villa Sarabhai in Ahmedabad, will recognize that these ever-changing compositions are rich echoes of the marriage of nature and building that Jeanneret perceived when he first took in all that was contained and exposed on the hill overlooking Athens. What affected him above all at the Acropolis was the integration of the temples into their site. The relation of buildings to their natural setting; the universal vistas; the equal importance of air, water, and light to stones and mortar—what was evident in the Greek monuments was to be palpable in all that Le Corbusier built.

So were the roles of color and light. “Never in my life have I experienced the subtleties of such monochromy. The body, the mind, the heart gasp, suddenly overpowered.”19 Now more than ever, he wished to create such thrills for others.

7

Jeanneret both worshipped and detested the godlike power of the Parthenon. He summed up the experience as “admiration, adoration, and then annihilation.” After twelve days of daily visits, he suddenly disliked going up there: “When I see it from afar it is like a corpse. The feeling of compassion is over.” Jeanneret began to sense the presence of death everywhere around him. The nights seemed “green,” with “bitter vapors” under the black sky. In the streets of Athens he saw—or thought he saw—corpses being carried by black-robed Orthodox priests; the skin of the exposed faces of the dead bodies was also green, with black flies swarming around them. “The torpor of the land” merged in his mind with the weighed-down clouds.20 Yet for nine more days, he kept going back to the Acropolis. He was in love, then out of love; ravenous, then satiated; ecstatic, and then despondent.

Finally, Jeanneret had had enough. He later wrote L’Eplattenier, “I’ve seen Eleusis and Delphi. All well and good. But for three weeks I’ve seen the Acropolis. God Almighty! I had too much of it by the end—it crushes you until you’re ground to dust.”21

At the Acropolis, September 1911

8

In Athens, Jeanneret received a letter from Charles L’Eplattenier, asking him to come back to art school and form a new division there.

Having taken this long voyage to cure himself of his previous misery and, he wrote Ritter, having succeeded in enlarging his vision of life and acquiring a new serenity, he was tormented by the offer. The need to reconsider his future was a “catastrophe.” He feared that if he decided to go back, he would become like L’Eplattenier, a prospect he equated with spiritual death. But he had to contend with reality and the obligation he felt to return to his hometown.

Jeanneret told Ritter that he blamed himself for his suffering; his own tyrant, he tortured himself. Since the age of fourteen, he had pushed himself mercilessly, so that now he was more anxious by the day and made women afraid. His brother, Albert, by contrast, was generous, full of sunshine and love.

Miserably, he was resigned to accept L’Eplattenier’s proposal but still would not give his parents the satisfaction of knowing he was coming home. He told them only that he was leaving Athens and going to Calabria rather than Cyprus because of his digestive issues: “I’m dragging my guts around Athens…it’s the cooking here that’s doing me in.” He believed he would stop his diarrhea with Italian macaroni. “I think that’ll put the cork in it.”22

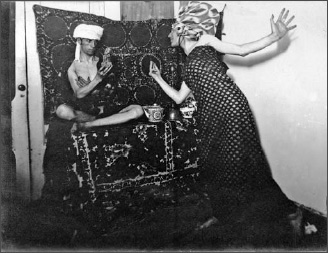

In Pompeii, the cure worked. But in Rome he became upset about a misunderstanding. He learned that a postcard he sent home from Constantinople showing himself and Klipstein disguised as women had flopped. His parents “failed to recognize their own son with towels for breasts and purebred elbows” and were not amused by the “bazaar finery.”23 Then, on October 4, Jeanneret learned that his father’s workplace and his aunt’s apartment had been destroyed by fire.

He responded by writing that, although the fire was a serious matter, it neither troubled nor saddened him. While he offered to rush home if his help was needed, the event was an opportunity for a fresh start: “Now comes a resplendent purity,” he assured his parents.24 Jeanneret told his mother and father that he had, however, cried because of the probable loss of two books that he wanted to use for his own research: the Encyclopedia and La Patrie Suisse. He also grieved the loss of “Papa’s suspenders, his smoking-jacket, his slippers, his checked celluloid cuffs.”25 But the idea of giving everything up and starting all over again was consolation.

He longed to be in the same situation. From Rome, Jeanneret sent L’Eplattenier a postcard declaring, “I hear the death-knell of my youth.

Within a month or less it will be over. Ended. Another man, another life, clear horizons, and a road between walls…. Of course I’m often sad about it: gray fits of melancholy mingle with the joys of my return. I leap from dark to light and back again, and there’s no doubt something harsh and tragic remains.”26

Auguste Klipstein and Charles-Edouard Jeanneret performing the dance of Salomé in Pera (Istanbul), July 1911

But Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had now made a resolution. If he had to be back in Switzerland, at least he could use it as a stepping-stone toward becoming an architect. His lack of the requisite diploma was no obstacle.