XXII

1

Le Corbusier was becoming everything Charles-Edouard Jeanneret intended. By the end of 1923, not only had he published Toward a New Architecture and begun the villas La Roche and Jeanneret, but his latest paintings were on view at the Salon des Indépendants and in the gallery of the renowned art dealer Léonce Rosenberg on the rue de la Baume.

Then he made a decision as calculated as the adoption of his new name. He decided to conceal his “painter” side. For the next fifteen years, he painted for four to five hours per day, but he was resolved to show the work to virtually no one, claiming that it would detract from the way he was regarded as a designer and urbanist.

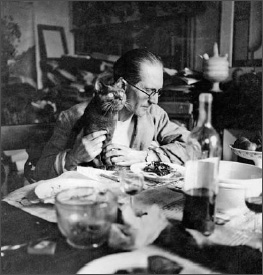

At 20 rue Jacob, mid-1920s

As an architect, his international importance was soaring. Swamped with work, in the spring of 1924 he complained to Ritter about the hectic pace, but, in his usual disjointed language, exulted in the overload: “Existence continues to be exhausting but quite interesting, complex, impossible even to dream of such a thing as rest: one is squeezed into rigid postures. Life augments, and difficulties as well; luckily, one is not too fond of money and there are other satisfactions.”1

Even if money was tight, there was now enough work for Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret to open a larger office. They did so in the hallway of a Jesuit convent at 35 rue de Sèvres, just a minute’s walk from a major Métro stop and in the middle of one of the liveliest neighborhoods in Paris. They were diagonally across from the great department store Le Bon Marché and half a block from Le Lutétia, the largest hotel on the Left Bank, with the perennial whistles of its doormen summoning taxis for visitors from all over the world. The artists’ neighborhood of St. Germain, and Le Corbusier and Yvonne’s own apartment, were nearby. The setting where Le Corbusier was to create the buildings that have come to define modern architecture lay behind a quiet, classical facade. It was as seemingly traditional as its boss’s appearance. Yet once one had passed through the convent and a courtyard, under the surveillance of a concierge, and passed through “a huge, white gallery-corridor some thirty yards long, five yards wide,” another world awaited.2 Up a dark flight of stairs, one was in a secret hub of power.

This was the “old, dirty, smelly, and brokendown” atelier.3 It had the same form as the corridor below. On one side, windows faced the courtyard; on the other, a long wall backed up on the Church of Saint Ignatius, from which Gregorian chants or Bach fugues could be heard. There was a hodgepodge of drafting tables, easels, and architectural models, with drawings hanging everywhere. In the beginning, the average number of people working in the office was about twelve; in time, it would swell to thirty.

Once he was in the new office, Le Corbusier established a routine he pretty much maintained for the rest of his professional life, except when he was traveling or stymied by a world war. He started his day at 6:00 a.m. with forty-five minutes of calisthenics; then he served Yvonne her morning coffee. They breakfasted at 8:00. For the rest of the morning, he painted, made architectural sketches, or wrote. By the time he arrived at the office at 2:00 p.m., he was charged with new ideas and put his employees to work making alterations to what they had done at home in the morning. If the afternoon went poorly, it wasn’t long before “he would fumble with his wristwatch—a small oddly feminine contraption, far too small for his big paw—and finally say, grudgingly, ‘It’s a hard thing, architecture,’ toss the pencil or charcoal stub on the drawing, and slink out.”4 But generally, by the time he headed back to the apartment for his evening pastis with Yvonne—she liked him there by 5:30—he felt triumphant.

He rarely socialized. Occasionally he and Yvonne ate with friends at the St. Benoit, their neighborhood bistro, or Le Corbusier recieved visitors like Gropius—the director of the Bauhaus, where Le Corbusier was greatly respected, who called on him for the first time on his honeymoon in 1926—but for the most part he devoted his time to designing, painting, or being quietly at home.

2

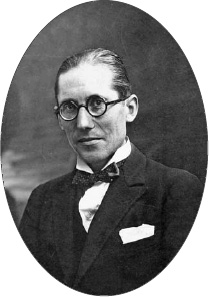

Le Corbusier did, however, delight in proselytizing his new faith to a widening audience. He lectured on architecture and on “L’Esprit Nouveau” at the Sorbonne early in 1924 and later in the year in Prague and Geneva. His lecture technique became legend. Dressed in his wide-lapeled, double-breasted suit, and hand-tied bow tie, with his signature round glasses and hair brushed back hard off his forehead, Le Corbusier spoke and simultaneously drew with feverish intensity. In charcoal, colored pencil, pastel, and chalk, he made his visions of urbanism more concrete by sketching away freehand on long bands of paper, about a yard wide, that he had unrolled and tacked to the walls. It might be tracing paper, cheap brown wrapping paper, or fine cream-colored stock, but the method was always the same.

The architect never used notes. Rather, he gave the impression that his ideas were still being developed. His audience felt the excitement of his thinking process. Sometimes he left meters of paper on the walls afterward; to this day, there are architects who proudly hold on to these souvenirs of having witnessed Le Corbusier in the act of creation.

LE CORBUSIER treated himself like an enterprise that needed to produce annual reports. Starting in 1924, he began to work on the publication of The Complete Work of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret. By 1938, there were four volumes. Once that publication ceased, it was replaced by Le Corbusier: The Complete Work—a series in which, for the rest of his life, he wrote texts to track his achievement for others.

The people whom he wanted to impress above all with his autobiographical report card on his diverse achievements were his mother and father. He made clear to them, however, that the modest house he was designing for them, to be on Lac Leman, was the building that counted most of all.

3

In June 1924, Edouard, as he still was to his parents, sent them a postcard saying he was finishing plans for their new home and was about to send them all the details to hand over to the builder: “This house will be exquisite, and I am quite happy with the solution arrived at. Count on us, we know what must be done so that there will be no delays.”5 The “we” was he and Pierre, in whom they could have confidence as a fellow member of the Jeanneret clan.

While Edouard never referred to the disaster of the Maison Blanche, he now gave them a house that was completed on schedule and within budget. After their five years of exile in rented chalets, the retired watchcase enameler and piano teacher would finally have a little paradise.

For more than a year, Edouard had been negotiating, in a fairly nefarious manner, to buy a parcel of land from some farmers in Vevey. When he was there with his parents for the Christmas holidays in 1923, he had written Yvonne, “One must use a certain amount of cunning with these peasants, and one spends one’s time in grim dives where the talk goes on forever. I am exhausted and invoke the aid of all the devils in creation to reach a conclusion.”6 Nine months later, it had all paid off; in September 1924, he wrote his girlfriend back in Paris, “The little house will be like an ancient temple at the water’s edge.”7 By the time he arrived there on December 23, Le Corbusier had seen to every detail—the linoleum for the floors, the medical-style sink, the plain-white open-weave window curtains that were such a contrast to the patterned brocades of rue Léopold-Robert. This house for two people, without servants, looking south over the lake, was without an iota of waste, as impeccably organized and efficient as it was celestial and poetic. All that was left to do before Christmas was arrange the furniture, which Le Corbusier quickly did. Once he had put the last object in place, the thirty-seven-year-old son had achieved his dream.

LA PETITE MAISON is a cosmic house. Inside, one feels perfectly aligned within the solar system. Daylight pours in through a high window facing east. To the south, a window eleven meters in length opens the interior to the water. The oceanic Lac Leman is separated from the house by only a couple of meters of land; to be in the living room is like being on board a ship, with only the deck between you and the sea. The reflections and smooth light from the lake flood the rooms.

The Maison Blanche had been excessive; La Petite Maison is reduced and taut. In this structure measuring four meters by sixteen meters—a sequence of four squares—the harmony of the plan pervades. Another architect might have made such tight organization seem stingy. Le Corbusier renders it, for all the smallness of scale, grand and sublime. The little house is neatly subdivided into rooms that provided everything Georges and Marie needed. There is a salon with a simple dining table cantilevered under the window ledge, their bedroom, and a compact galley kitchen. On the east end, there is a guest room that doubles as a second sitting room or, alternatively, can open up completely—thanks to a wall panel on hinges—to become part of the salon. To accommodate overnight visitors, Le Corbusier included a hidden closet, an extra mattress stored in the basement, and a sink concealed within a wall.

The writing/dining table is the first example of the variation that reappeared in Le Corbusier’s own cabin at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. It is a straightforward rectangular wooden slab supported by iron stovepipe legs. But while this table was as modern as the house for which it was custom fitted, Georges and Marie used old country chairs that recalled the couple’s earlier years. Similarly, the elegant and old-fashioned desk Edouard had designed for Marie for the Maison Blanche, with its space for knitting needles, is in the bedroom. For all the simplicity of the architectural program, the house is not cold; it invites the charms of one’s life experience to be present.

The tiny enclosure of the sole toilet in the house does not have an inch to spare. At the same time, because of a window high up in this vertical cubicle, it has the light of a chapel, ennobling the act of sitting on the toilet. In the separate bathroom, Le Corbusier put small vertical windows and skylights over the tub and sink, as he did in the closet: light, intangible and born to the sun, changes everything.

IN 1930, Le Corbusier added a “fruitier” to La Petite Maison. This eagle’s nest for his own use allowed a view akin to what he had first experienced in the monasteries on Mount Athos. From this austere box on top of the villa, he could set his sights on the horizon.

The desk and chair in the fruitier are on a platform. This desk is even simpler than the table in his parents’ living space; one end of its concrete top rests on a ledge, while the other is supported by a single stovepipe as delicate as a bird’s leg. Le Corbusier had an ability to take strong industrial materials and imbue them with feathery lightness. The stairs to reach this aerie have a banister of tubular steel, with a graceful turn below and a handsome mirror image of that turn at the top to provide a sense of balletic grace; its concrete steps are scaled to invite easy footwork. What is weighty becomes weightless.

THE LARGE PLATE-GLASS sliding window overlooking the lake in the main space of La Petite Maison encourages the act of seeing. And what a feast that is, thanks to the play of colors within the interior. The north wall of the living/dining room is painted a light aquamarine; the east is cobalt. There is also a range of grays. The bedroom is salmon. Brown trim serves like a colored tinted mat surrounding a picture. Playful cutouts of geometric shapes, high and low, provide the satisfaction of abstract art.

All of this occurs under a flat roof that is covered with grass—a superb play of the man-made and the natural. This dwelling is the perfect shelter in which to contemplate the universal. The views, and that deliberate melding of earthly growth with the calibration of human needs, inspire thoughtfulness and reverence.

In this small, private house—his gift to the people he cared about the most—the architect who publicly swaggered across the worldwide stage, who issued pronouncements for humanity and tried to replan our cities, was charming, poetic, and divinely quiet. He sanctified everyday living while making it easy and practical. To the father who had shown him the sky and the earth, and to the mother who opened his soul to the rhythms and harmonies of music, he returned these qualities in a new form.

SHORTLY AFTER La Petite Maison was completed, the community council of a nearby town got together to forbid the building of any modern structures within the territory it governed. It did so in the name of preservation of the scenery. That slap confirmed Le Corbusier’s views of Switzerland. In little time, the hostility of his native land became even more apparent; the struggle for beauty would not be easily won there. But his house for his parents was, however slight, a victory.

4

The end of February was almost invariably a time of winter lows for Jeanneret/Le Corbusier. Nineteen hundred and twenty-five was completely different.

He had garnered the respect of the other pioneers of modern architecture. This was evident when Mies van der Rohe, vice president of the Deutscher Werkbund, became project director of a major exhibition in the Weissenh of section of Stuttgart to show the latest approaches to the modern home and gave Le Corbusier the single best location, overlooking the city. Le Corbusier did two houses that expanded on the Citrohan ideas, essentially boxes on pilotis with simplified, versatile plans. Their architecture was praised for its connection to the natural surroundings while criticized for its cost; these houses were more expensive per square foot than anything else at the exhibition.

Ca. 1920

The Weissenh of houses are examples of Le Corbusier’s work that must be considered in the context of their site rather than in photographic reproductions that render them as isolated objects. In that neighborhood of Stuttgart, one is on a hillside, near a bustling city center but facing a vast panorama of fertile mountains and vineyards. Especially in springtime, the shimmering white plaster of Le Corbusier’s shoe boxes of modernism is a perfect foil to the fields of buttercups and bluebells catching the sunlight all around them. The utterly simple, bold pavilions, one sprawling and the other compact, one facing south and the other east, are resting points on the earth that gracefully assume second place to their setting.

Remarkably, the rolling countryside of southern Germany here resembles the surrounds of Delphi; this is more a fertile corner of the world than a particular place, with its timelessness and universality accentuated thanks to the way Le Corbusier’s architecture recedes and deliberately presents a view of the distant panorama rather than the modern city. He succeeded in making Germany, the country he disliked, distinctly un-German.

The buildings serve the setting, yet they are anything but timid. These elegant rectangular blocks are both brave masses, standing strong and clear. Lighter than the villa he was simultaneously designing in the Paris suburb of Garches, they are more confident than the studio-house for Ozenfant, their bold forms exquisitely elegant without being in any way fussy.

The smaller house has a balcony that floats off of it. Its pilotis are thin and graceful, bringing to the forefront Le Corbusier’s idea of the resemblance of architecture to music, with the massing of the house the kettledrum and the balcony and these supporting elements the flutes. One goes from seeing and hearing the full orchestra to a meandering solo.

The larger house combines inside and out as a totality. Nature penetrates its balcony; the sky and the surroundings are present throughout. Le Corbusier was an architect of air; space, more than bricks and mortar, was his medium. He used the sturdiest, most durable of new materials, as befit this exhibition of current construction practices, yet rendered them weightless. A refinement and touch are apparent in every lean staircase, the tautness of the window trim, the grace with which each space opens to the next. How delicate was this bold vision that allows one to join the birds!

5

On February 24, Le Corbusier wrote Ritter his latest assessment of his life: “I realized that after ten years of really tumultuous, painful (oh very!), and exhausting life that I had rounded the cape of storms and was in fact a very happy fellow, leading an ideal life.” With no time wasted socializing, he was doing what he loved: practicing architecture, painting, and writing. It made him “gay as a sparrow, more optimistic than ever, stubborn as a mule, and always focused on the same goal.”8 Now realizing more than ever what a quagmire his hometown had been, he credited Ritter, the only person he felt had had confidence in him, for his escape.

“For me architecture is a game,” he wrote confidently. His struggle was with painting, “which torments me endlessly, plunging me into tremendous anxieties.” But now, at least, everything was coming into perspective. His romance with business and the goal of making his fortune were behind him: “I want you to understand that for me money has lost any luster it may have had. Having earned it, but having always invested it in risky ventures, I have never had it in my hands for long; having lost it, I felt nothing. But the only good result is being able to reach that focus where, in the work itself, you feel yourself on your way.”9

Le Corbusier was determined to live simply and avoid distraction from his work: “A harsh, precipitous life furiously filled to the brim; and the modest situation of a monk (whose little heart has his little friend), in a white room, overlooking a garden. Le Corbusier is not Peter Behrens, who had a lackey to watch him eat.”10 His “little friend”—presumably Ritter knew who she was—was all he needed.

THE CLIENTS were at the door; he was preparing for exhibitions; new texts were going into print. At the same time, Le Corbusier was devising the urban scheme that, for many people, was to cast him permanently as the devil. This bombshell that the architect was about to let drop became the reason that, on first hearing Le Corbusier’s name, many people still speak of him as the man who wanted to destroy Paris and as the demon who damaged cities all over the world.

This was also a time of major personal change for Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. It was the beginning of the end for his father. Freud has said that a man’s father’s death is the beginning of his maturity. As Le Corbusier began to assume his new role in the oldest surviving generation of men in the family, he gained a confidence of terrifying proportion.

6

With the City for Three Million, Le Corbusier had come up with an abstract urban scheme that could go anywhere. Anticipating the International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts that was to open in April 1925, he devised a new plan for Paris itself—or, rather, for a city that would be dropped down into the middle of an erased Paris. He had reconstructed his parents’ lives by excising them from one existence and transplanting them into another; now he imagined doing so for most of the population of the French capital. He also conceived the ideal single-family dwelling that could be produced, as if with a cookie cutter, on an infinite scale and that would be the cell of this new metropolis. That his urban proposal meant bulldozing almost all that was already there did not trouble him.

The central notion behind his scheme was his belief that the automobile had changed everything. Having observed Paris empty out during the summer months, Le Corbusier had been anguished by what happened when people returned from their August holidays: “Then there came the autumn season. In the early evening twilight on the Champs-Elysées it was as though the world had suddenly gone mad. After the emptiness of the summer, the traffic was more furious than ever. Day by day the fury of traffic grew. To leave your house meant that once you had crossed the threshold you were a possible sacrifice to death in the shape of innumerable motors. I think back twenty years, when I was a student; the road belonged to us then; we sang in it and argued in it, while the horse-bus swept calmly along.”11

In Le Corbusier’s mind, the presence of all these cars became hallucinatory: “On that 1st day of October, on the Champs-Elysées, I was assisting at the titanic reawakening of a completely new phenomenon, which three months of summer had calmed down a little—traffic. Motors in all directions, going at all speeds. I was overwhelmed, an enthusiastic rapture filled me. Not the rapture of the shining coachwork under the gleaming lights, but the rapture of power.”12

He assumed for himself a force equal to that intoxicating energy of the automobile.

The simple and ingenuous pleasure of being in the centre of so much power, so much speed. We are a part of it. We are part of that race whose dawn is just awakening….

Its power is like a torrent swollen by storms; a destructive fury. The city is crumbling, it cannot last much longer; its time is past. It is too old. The torrent can no longer keep to its bed. It is a kind of cataclysm. It is something utterly abnormal, and the disequilibrium grows day by day….

Surgery must be applied at the city’s centre.

Physic must be used elsewhere…. We must use the knife.13

7

The International Exposition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts had been in the planning stages since 1909. This show, which subsequently gave birth to the term “Art Deco,” was to reveal “modern tendencies,” reflecting the era of automobiles and airplanes, in temporary structures especially erected between Les Invalides and the Grand Palais, on both sides of the Seine. Le Corbusier liked the idea but not the organizers. In March 1925, he wrote, “Countless pavilions, all decorated and decorative, are being built, truly a spectacle which astonishes me and produces the impression of pure madness. I didn’t dream the level was so low.”14 The architect was particularly outraged by Emile-Jacques Ruhlmann’s salon, which he said was just an updated version of an elegant sitting room of an earlier era that violated the concepts of the exhibition.

Le Corbusier, however, honored those guidelines. His intended Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau was to demonstrate how standardization could be applied to domestic building in a housing type made entirely through industrial means. But the organizers quibbled with this notion. “When I submitted my scheme in January 1924 to the architects-in-chief of the Exhibition,” he later wrote, “it was categorically rejected. They wished me to illustrate the theme ‘An Architect’s House.’ I answered, ‘No, I will do a house for everybody, or, if you prefer it, the apartment of any gentleman who would like to be comfortable in beautiful surroundings.’”15

The initial dismissal of his proposal delighted rather than discouraged the man who was convinced that he was the savior of humanity—and who expected the concomitant opposition. The dream that he could give visual beauty to the masses was too great to go unchecked. Naturally, the notion of building housing as practical and efficient as modes of transportation was too revolutionary for the mediocre minds in charge.

The official disapproval continued. In April, when Le Corbusier presented a new design for a structure at the exposition, he got no response. When a site for it was finally granted in September, the location was remote and contained trees that could not be moved.

Le Corbusier let it be known that he was injured and disgusted. But his enthusiasm did not wane. He now sought financial backing for this pavilion by approaching various automobile companies. The car, having destroyed the city in one form, could be the source of its salvation in another.

Le Corbusier offered Jean-Pierre Peugeot and André Citroën what we would today call a “naming opportunity” in exchange for funding. Peugeot was honored but refused; Citroën didn’t understand. André Michelin was in Morocco. But Monservon, who worked for Gabriel Voisin, went to the office on the rue de Sèvres. Voisin, a manufacturer of aircraft with an automobile division, agreed to be the patron and gave twenty-five thousand francs. Henri Frugès, heir to a sugar cube factory in Bordeaux and a Le Corbusier supporter, matched the amount, and the three-hundred-square-meter reinforced-concrete structure was erected. The new plan for Paris, which Le Corbusier named for Voisin, was revealed inside it.

THE CONCEPT was megalomaniacal. Declaring large sections of Paris “antiquated…unhealthy…[and] overcrowded,” Le Corbusier called for destroying hundreds of acres of the Right Bank, including much of the charming ancient quarter called the Marais. To ease the excessive traffic on the Champs-Elysées, he proposed building a highway that would cut through the partially leveled city. Le Corbusier retained some remnants of the past—“certain historical monuments, arcades, doorways, carefully preserved because they are pages out of history or works of art”—but the rest would go.16

One of the most consistent misunderstandings of the Le Corbusier legacy, however, is the notion that he intended everything to be destroyed as if by a bomb. The error is often reiterated that he wanted to obliterate the place des Vosges—that, if he had had his way, virtually every trace of Paris’s architectural history would have disappeared. The Plan Voisin was radical—in most people’s judgment outrageous—but, although it called for a total rebuilding of much of the area between the Seine and Montmartre, the intention was always for the place des Vosges, the Louvre, the Arc de Triomphe, the Palais Royal, and various other buildings to remain. Le Corbusier aimed to make them all the more visible. The goal was not the eradication of the past but a selective pruning that would leave the best behind to be savored in a new way. The great open spaces, such as the Tuileries and the Invalides, that had been essential to the urban idea of Louis XIV, Louis XV, and Napoleon would be returned to their former glory.

In front of the diagram of the Plan Voisin, 1925

Driving a Fiat on the roof track of the Lingotto factory in Turin, mid-1920s

But Paris would now consist mostly of variations of the building type seen in the City for Three Million. Le Corbusier envisioned carefully spaced, cruciform skyscrapers, 245 meters high. He explained that these would attract investment from America, England, Japan, and Germany. There would, in addition, be blocks of new residential units.

THE LITTLE-KNOWN TRUTH is that although Le Corbusier invented and presented the Plan Voisin, he did not intend for it to be followed. He neither imagined it really would be done nor thought it should be. “The ‘Voisin’ scheme does not claim to have found a final solution to the problem of the center of Paris; but it may serve to raise the discussion to a level in keeping with the spirit of our new age,” he wrote at the time.17 No utterance of Le Corbusier’s is more important to a correct understanding of his legacy. He had not wanted to ravage a world he loved. He had been deliberately provocative; he had done his utmost to stimulate new thinking; but what he put forward as a hypothetical proposal was just that.

8

The Plan Voisin and the City for Three Million were displayed in two large dioramas, each about one hundred square meters, in a rotunda within the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau. Detailed plans for the cruciform skyscrapers and for entire colonies of these new dwellings hung on the walls inside this imposing silo.

The pavilion itself was the model for the standard residential unit that would have been reproduced ad infinitum in neat blocks at the outskirts of the new ideal city. If, to current eyes, the residential unit fits into a known canon of modernism, to its viewers in 1925 it offered as powerful a jolt as the urban plan. It was essentially an unadorned, unmodulated white concrete box with a facade sheathed in a taut, industrial-style window wall. The inside was punctuated by an enclosed garden with a tree popping through a circular hole in its roof. This last detail, a response to the exigencies of the wretched site, now became part of the general concept.

Walking near their office, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret had conceived of the scale after studying scaffolding in front of the three-story-high Le Bon Marché. They became convinced that human beings would profit if they followed that commercial model in residential architecture. Ceiling heights should be nearly doubled from the existing norm of nine to twelve feet to eighteen to twenty-two feet. Housing should be set back farther from the street and built higher than it had been.

Inside, the pavilion depended on commercial lighting fixtures made for shop windows. Some of the chairs and tables came from a catalog for hospital furniture; most of the cabinets and closets were built-in. The glassware to be used domestically had been made for laboratory experiments. Le Corbusier explained that the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau and its contents were “the fruit of a mind preoccupied with the problems of the future.”18

Less advanced minds did not see it this way. Controversy broke out. The jury of the exhibition, according at least to Le Corbusier’s subsequent account, wanted to give the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau and the Plan Voisin its highest design award. But its vice president, none other than Le Corbusier’s former employer Auguste Perret, declared, “It’s ridiculous. It doesn’t hold together, it lacks any logic. There’s no architecture here.”19

Exterior of the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau, Paris, 1925

The Building Committee for the exhibition erected an eighteen-foot-high wall in front of the new pavilion to keep the public from seeing it. Whether this was a construction wall, simply meant to keep the project under wraps while it was in process, or deliberate censorship, as Le Corbusier makes it sound in his accounts, is unclear. But Le Corbusier always presented that wall as a symbol of the wishes of the forces against him to conceal his work, even implying that it was re-erected after the inauguration of the pavilion. He falsified and dramatized the maneuvers of the opposition; the pavilion remained plainly visible after its delayed opening. Nonetheless, the disapproval was real.

9

The printed invitation that served as an admissions card for the inauguration ceremony invited its recipients to enter the Grand Palais on Friday, July 10, at four o’clock in the afternoon. In blocky, sans-serif type, as lean and right-angled as the pavilion itself, it declared, “This pavilion is better hidden than any other in the exposition.”20 Le Corbusier wanted no one to overlook the unforgivably obscure location. But once people made their way to this structure tucked into the garden between the two wings of the Grand Palais, they were in a new world.

The pavilion was elegant: light, graceful, imparting a feeling of cheer and optimism. Inside as well as out, it was clean, fit, and energetic. Those laboratory jars and hospital furniture now used for domestic purposes were so charming and effective that they were to infiltrate the culture, so that today there are carafes resembling chemists’ flasks for sale in housewares stores all over the world.

There were ingenious wardrobes and clothes cupboards built into walls or neatly suspended from them, as well as imaginative bookshelves and storage units, made out of metal by a manufacturer of office equipment, that allowed maximum space in the rooms. The new aesthetic was a revolutionary invitation to be practical, to live in a house that is easy to clean and maintain. At the same time, the clear and engaging forms were arranged at lively angles meant to lift human spirits. And bouquets of flowers burst joyously in the tidy assemblage. As always, Le Corbusier’s vision was a stage on which the splendor of nature could perform in plain view.

THE PAVILION was hung with work by the same pantheon of modernists as the Villa La Roche, among them Braque, Gris, Léger, Lipchitz, Ozenfant, and Picasso. Jeanneret/Le Corbusier’s own paintings were also displayed, in contradiction of his vow to keep that side of his creativity under wraps. Certain qualities of Jeanneret’s Purist canvases—the “‘marriage of objects in sharing an outline’ and his use of so-called regulating lines”—were echoed in the architectural organization. Similarly, Le Corbusier’s deployment “of color in his architectural interiors is closely related to the palette of his canvases.”21 For all the restraint and austerity of the ornament-free shell, the overall symphony was immensely rich.

ROBERT BRASILLACH—a journalist who, twenty years later, was executed as a collaborator with the Vichy regime—wrote that the furniture, and the ideas on furnishing, would last for a very long time. But the manufacturers who the architects hoped would take up his ideas showed no interest. Having imagined the pavilion and its fittings being repeated all over the world, Le Corbusier felt mocked and lambasted.

In his new book, The City of To-morrow and Its Planning, he defended himself. “This is a sentiment born of the most arduous labor, the most rational investigation; it is ‘a spirit of constructions and of synthesis guided by a clear conception,’” Le Corbusier writes of the Pavilion and the Plan Voisin, without attributing the quotation.22

His 1925 The Decorative Art of Today intensified the propaganda campaign. It shocked the public in part because it virulently attacks Art Deco, which had become immensely popular. The book criticizes majority taste past and present. Blasting museums for “their tendentious incoherence,” it decries concepts of decoration and style in general, and laments, in particular, the contemporary plagiarism of folk art—which Le Corbusier wanted only in its genuine form.23

Le Corbusier cites, as objects worthy of display in a museum, “a plain jacket, a bowler hat, a well-made shoe, an electric light bulb with bayonet fixing,…and bottles of various shapes (Champagne, Bordeaux) in which we keep our Mercurey, our Graves, or simply our ordinaire… a bathroom with its enameled bath, its china bidet, its wash basin, and its glittering taps of copper or nickel…a Ronéo filing cabinet with its printed index cards, tabulated, numbered, perforated, and indented.”24 What many of us today consider the courage and imagination of that declaration of beauty struck contemporary readers as heresy.

Le Corbusier reproduces photographs of various types of fuselages and extols their merits, case by case. In this highly personal version of the history of ornament and design, he denigrates any number of classics with one of his dicta of the type that set the public on its ear: “I notice that a whole mass of objects which once bore the sense of truth have lost their content and are now no more than carcasses: I throw them out.”25

Those who were not stunned or enraged by the narrative admired its bravery. The poet Paul Valéry wrote Le Corbusier, “Monsieur, I have only one word to tell you about your book (The Decorative Art of Today), and that is a word I use rarely: admirable. I am embarrassed, moreover, to write it to you. I think alike with you on most of the subjects you deal with. It is all too easy for me to approve of my own sentiments…. Please be assured, Monsieur, that I hold your work in singular esteem, that I shall make it known to others to the best of my ability, and accept the expression of my gratitude and of all my sympathy.”26

But no praise was sufficient for Le Corbusier to abandon his role as a long-suffering martyr. He made himself the victim of “the generation of our fathers who protest, resist, refuse, mock, laugh, insult, deny. We are poor and we run round the race-track, exhausted and emotional. Our fathers sit in the stands…. Our fathers are smoking fat cigars and wearing top hats. They are fine, our fathers, and we are what we are—thin as street cats.”27 For the dapper and urbane son who sported fine Paris hats to portray the older generation in that way was more than ironic. His own father was lean and worn out by a lifetime of hard work. He was also on some level the man whose approval Le Corbusier still most craved.