XXIII

1

On November 8, 1925, Marie Charlotte Emilie Jeanneret-Perret wrote both her sons. “Our dear papa is lost,” she informed them.

Georges had stomach cancer that had spread and formed a tumor in his liver. He had no idea how sick he was; nor could she let him find out. The doctor, who had told her this in private, said that one should hope only that Georges’s suffering would not be prolonged. If he had a hemorrhage, he would be spared extended pain. Marie was now following the doctor’s counsel and preparing the house so that he could be cared for there. Nurses would be required, she informed Albert and Edouard. But in fact their rugged mother was constitutionally incapable of hiring outside help and intended to do everything herself.

On November 29, anticipating Georges’s birthday two days later, Edouard sent his father a letter that focused on the heating system—he hoped it was working well—and on the beauty of the winter landscape. From Paris, he conjured the eternal setting of Vevey: “In winter this site is quite stately, vaster than in summer and of an impressive, polar sweetness. One no longer sees the mountains in the background, and the lake seems a sea.”1

Having latched onto other father figures as intellectual and professional mentors—L’Eplattenier, Ritter, and Auguste Perret among them—Le Corbusier had come to cherish his actual father as the model of beatific kindness. He wrote the dying man: “You have had many evidences of affection during your sickness. You see that you are surrounded by esteem and respect. By living without the fierce egoism which makes everything ugly, one creates around oneself a beneficent atmosphere. One would not realize this if, with the sudden arrival of the anguish of disease, those who breathe that atmosphere did not feel that their lungs would now lack it. It’s quite human, such testimonies come only at acute times, moments of crisis. You will have had not pride, for that is no longer suited to your age, but a certain emotion at feeling the sincere sentiment that surrounded you.” The younger son was overcome with admiration for his father’s “spirit…so calm, so detached from all pettiness.”2 He also told his ailing parent that he and Albert feared that their mother was not up to the task of taking care of an invalid. They had begged their Aunt Marguerite to hire someone at least to run errands for her.

At the end of November, Edouard provided his father with a thorough update on his work. He was upset that the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau was to be “cut into pieces by pneumatic concrete drills and transported by trucks to the suburban banks of the Seine,” but the first two houses of a new project at Pessac, near Bordeaux, were complete. “So much for my little gazette of accomplishments,” he summarized, going on to cheer up the invalid with the news that Albert was becoming more stable thanks to Lotti’s “great serenity of spirit.”3

As for his own female companion, Edouard made no mention of her to the dying Calvinist. But when Georges’s condition worsened a couple of weeks later and Edouard rushed to Switzerland, it was Yvonne to whom he poured out his woes. He had gone to see his father in the hospital. They had opened Georges’s chest and determined that the end was near. “If you knew how sad it is, how distressing, really lamentable to see my poor papa,” he wrote. “His body is awful to look at: a skeleton, and he has no blood left in him; he’s no more than a transparent man, and his voice is already quite remote. He thinks only of others and never complains, although he is in pain.”4

His mother, he told Yvonne, was “heroic.” She smiled in front of her dying husband, comforting him and making him believe that all was going well. Then she would go into the small kitchen of La Petite Maison and cry. That self-control in tandem with her tenderness was Le Corbusier’s ideal.

It was Christmas Eve. As Charles-Edouard Jeanneret sat in the small and exquisite villa he had built for his parents to savor the rewards of life as they looked out at the vastness of Lac Leman, he knew this was to be the last Christmas with all four of them alive.

2

Le Corbusier returned to Paris to be with Yvonne at New Year’s, although he told his parents it was for work. On December 31, he wrote his parents about the extent to which he felt

family ties. I am aware of the great friendship which unites us. And the gratitude I feel toward you who raised me allows me to tell you that you can count on me.

My dear good emaciated Papa, happy new year, good luck, bon courage, and take care of our Maman who is not so good at taking care of herself.

My dear good Maman, bon courage, and count on the support of your sons.

Swift recovery for dear Papa.

Affections from your ED.5

EDOUARD was plagued that he had left in the middle of their last holiday time as a family—in part because Albert had remained on the scene. But if he could not win in the role of more devoted son, he could certainly out-achieve his brother. At the start of January, he informed their parents that the magazine Architecture vivante was about to publish an article on La Petite Maison. Even as he mocked himself by adding, “I am incorrigible,” how proud he was to tell his dying father that the house was being honored in the most beautiful review in France.6

3

Within a few days, Edouard was called back to Vevey. He arrived on the morning of Sunday, January 10. Georges was to remain conscious for only twelve more hours. In those last moments with his mind still functioning, the elder Jeanneret discussed only what his son termed “the essentials” of life. He did not waste his breath on anything else.

At seven in the evening, the former mountain climber summoned his wife and sons. He wanted all three together at his bedside at the same time. “It’s over. I’m about to die. Love each other, help each other, be faithful to each other”—these were Georges Edouard Jeanneret’s departing words.7 Age sixty-nine, he then fell asleep, never to waken.

Once his father was unconscious, Edouard lay down next to him. At four in the morning, he was aware that the older man was no longer breathing. He turned on the light. His father was dead, with one hand lying across his chest, the other positioned underneath his right ear. In Edouard’s eyes, his father was “tranquil, mild, without agony.” The son immediately picked up pencil and paper and drew the portrait of his dead parent. A week later, reflecting on his time with the corpse, Le Corbusier wrote Ritter, “If you knew what gentle joy I felt at being close to him this way.”8

SHORTLY AFTER Georges Jeanneret died, Le Corbusier wrote to Yvonne. He was aware now more than ever that the human values he prized most of all were exemplified by the man who had taken his last breaths at his side. “My Papa died beside me tonight, tranquilly, without a word,” he wrote. “All day Sunday he was with us, saying the essential things. I have a feeling of tremendous loss. My father is beautiful. He was the kind of man you recognized by his handwriting: limpid, pure, lofty, disinterested.”9

4

Le Corbusier was just then working on an unprecedented number of private houses. A week after Georges died, he revealed to Ritter and Czadra the drift of his mind at this peak of professional success. The architect skimmed his fountain pen at rapid speed across the surface of three large pieces of paper, in perfect lines that appeared to rest on invisible scoring and could only have been written by a skillful draftsman: “Yes, my father is dead. You knew how tenderly all four of us were united; the two sons and their parents loved and esteemed each other; there was never any shadow.”10

Le Corbusier pushed aside any trace of the tempests caused by the Maison Blanche and acted as if the disputes and differences concerning his early travels and career had never occurred. Rather, he celebrated the way that La Petite Maison, sitting only four meters from the lake, with its simple train-car form and magnificent vistas, had become “a place of well-being and a therapeutic of the heart.”11

Le Corbusier assured Ritter and Czadra that the house had provided his father with a marvelous tranquility in his final days: “So, my dear father has died in perfect peace. During the last two months that his end was certain, he had established himself in the little house on the lake like a solemn music between the noble landscape and the drama that was irrevocably fulfilling itself. At this season the site unfolds its vicissitudes, and a polar majesty impregnates the soul with mildness and repose.”12

Forty years later, near his own small house with its view of the water and horizon, Le Corbusier was, after an entirely different sort of lifetime, to try to replicate some of those same feelings.

THE EMOTIONS that consumed Le Corbusier in January 1926 belong to the sort of son who, having deliberately and ferociously gone miles beyond his own father, then idealizes the man he had been determined to outdo. “Did you know my father well enough to know how much, day after day, he identified himself with the serenity of this site?” he wrote. “On his mortal remains, one phrase: this was a man of peace. From his silence, from his meditation always concealed in his depths, emanated nonetheless a radiant force that acted upon everyone (and powerfully upon the humble). Dead, his hands crossed on his chest, in his white shroud, he was no longer Mr. Jeanneret; he was a reformer, a man of those great centuries of bold thought. My timid father was an audacious man. Before his gently but firmly formulated judgment everyone, his countless friends, were brought up short: this was the truth; there was no thought of interest underneath it; my father was clear, felt clearly, thought clearly. He always dreamed of palm trees and sunshine and smooth, simple houses; when his features became so distinct, the silhouette of his face revealed a sharp profile; one might have said: an Arab; at least, that shape of the skull and that nose where everything is outline and pure script.”13

Georges had dropped out of school at the age of twelve but never stopped learning. Having immersed himself in history books and atlases, he was a man of few words but great knowledge. To Ritter and Czadra, Le Corbusier now recalled his father as his greatest soul mate and champion. Behind his taciturn facade, Georges had a passion for all that his son had undertaken, and he demonized anyone who stood in the way of his success; Le Corbusier appeared to have forgotten all their differences.

The architect in particular admired the grace with which both of his parents had faced the certainty of death: “My mother has been admirable, violent and passionate as she is. This death has made her gentle and smiling, with a childlike soul, timidly beginning a new life.” He, too, had passed to another level of his existence. “One no longer has the right to remain a boy,” he wrote.14

For years he had chided his parents for their rigidity and insularity. Now he focused only on how much they had given him: “What happiness to have had a father and a mother whom you can somehow idealize; from whose example you can summarize qualities and constitute rules for your own life. About whom you feel that since the day of your first responsibilities they have guided you on your path. You pursue a tradition they have established. A line of conduct. Your life has a direction.”15

Having fought everything he found deadening in his hometown and in the profession of his father and ancestors, Le Corbusier now considered Georges Jeanneret his human equivalent of the Parthenon. “He knew so many things, divined and perceived by judgment, appreciation. An autodidact all the way. Where you had best take him was at the end, when he gave his opinion. One realized then that he knew. Bold, libertarian, whatever, but always so polite, so fond of politeness, and having the sense of the value of traditions. Did you know that by closing your eyes in order not to see, letting yourself go in imagination, you become proud to be from the Neuchâtel mountains. But when the distance is great enough, and your forgetting complete enough, then you construct a ‘type.’ I have that weakness of wanting to attach myself to something, for I should prefer that my ideas had a consequence rather than being my exclusive and personal property.”16

Now, rather than destroy the past, Le Corbusier was determined to harness the best aspects of his heritage, to go farther yet in giving his ideas worldwide consequence.

5

Fourteen days after the evening when he witnessed his father die, he wrote his mother, “So, to keep up with everyone, I spent the last 15 days on my feet from 9 in the morning till 2 hours past midnight without once sitting down, moving from one desk to the next.”17 His mother, who knew he had been back in Paris for only half that time, was used to the exaggeration. The important thing was that there was a flurry of activity at 35 rue de Sèvres and a wonderful team to produce all the square meters of plans; things were so good that Edouard let her know he would be able to buy her a new gas oven in Vevey. For Le Corbusier, the supreme antidote to bereavement was work, and he was convinced that with his success he could offer his mother the greatest possible comfort.

6

Henri Frugès asked the architect to build a new city on the outskirts of Bordeaux. Le Corbusier worshipped the industrialist’s intentions of showing his countrymen the best way to live. Frugès’s goal was for Pessac to have a standardized form of housing that would be life enhancing for the inhabitants and completely contemporary. It was to be well built and efficient, utilizing streamlined forms constructed of modern materials engineered according to the latest methods. “The purity of the proportions will be the true eloquence,” Frugès advised Le Corbusier.18

Le Corbusier had envisioned such a seer and patron in The City of To-morrow. Now he had found the real thing. Frugès was his idea of a hero out of Balzac: rich and idealistic, and not only a businessman but a painter, sculptor, writer, architect, pianist, and composer. At the same time, he understood the limitations of his own artistic talents and ceded to Le Corbusier the task of designing the workers’ housing they both hoped would become a prototype all over the world.

For Pessac, Le Corbusier devised a standardized home easily constructed out of reinforced concrete. Similar to the Citrohan and L’Esprit Nouveau structures, it had a bold, blocky exterior and an interior with a two-story living room and a neat warren of carefully prescribed spaces, as well as generous roof gardens. There was an ambient whiteness new to domestic architecture but also a radical use of color. Pale-green and dark-brown walls and an occasional light blue were deployed as vibrant accents in the whiteness. Le Corbusier believed that these aesthetic choices would lead the masses toward greater health and happiness and lend order to their lives.

Although some of Le Corbusier’s designs at Pessac were executed, the scheme was never completed. Early in the construction process, local builders became defiant because of the unusual ways of doing things and had to be replaced by a crew from Paris. The new team finished the first phase of the project in less than a year, but until 1929 the city remained uninhabited. Le Corbusier blamed the authorities, whom he considered to be the typical bourgeois bureaucrats who always impede progress.

Others faulted the architect and his patron for having cut corners: “The houses were created before a complete dossier was submitted to the Mayor’s office and a construction permit obtained,” according to Brian Bruce Taylor’s excellent history of Pessac. Additionally, Frugès and Le Corbusier had ignored French laws requiring “appropriate installations for providing and filtering water to be made at the promoter’s expense.” The project had been completed too quickly, in blatant disregard of those regulations, and the houses could not be sold until Frugès established “streets, water mains and drainage at his own expense.”19 By the time this was done in November 1928, momentum was lost for finishing the new city.

DETRACTORS COMPARED the architecture of the partially completed Pessac to Frugès’s sugar cubes. They maintained that the new housing had everything to do with the efficiency in manufacture and packaging that had made a fortune for the industrialist—and nothing with the charms of life. But even if it appalled its adversaries, it was spectacularly inventive and beautifully intentioned.

Visiting Pessac today, one sees both how Le Corbusier succeeded and how he failed. On the three streets he completed, the houses, in various states of repair, are jewels: superbly optimistic, clean, crisp, and bright. External staircases and balconies make lively rhythms against the smart, compact forms; the right angles and grids and parallel lines are like the drumbeat in a jazz orchestra.

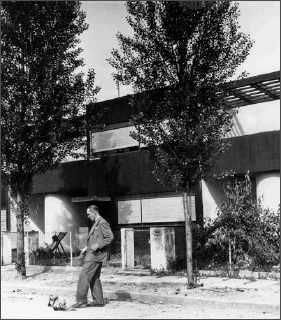

At Pessac, ca. 1926

Yet these structures are mostly faded and ravaged by time, or else repainted and changed so that their purity is gone. This is not happenstance; it occurred because the architect’s ideal was not what people wanted. And however charming the little community, it is nearly drowned by the mediocre architecture all around it. One must penetrate acres of desultory building to get to Le Corbusier’s and Frugès’s marvel. When one reaches it, it suggests the future—a future that, although constructed eighty years ago, seems bright but that was not realized as dreamed. Le Corbusier made a rarity; he did not affect the quotidian as he hoped. He created something enchanting and full of hope, but he did not come close to his intention of transforming the appearance of the larger world.

THE WRITER BLAISE CENDRARS, born about a month before Charles-Edouard Jeanneret in La Chaux-de-Fonds, was another local to take a new name, replacing “Frédéric Sauser” with an appellation that suggested fire rising from the ashes. On November 15, 1926, after a visit to Pessac, he, wrote Le Corbusier. “The ensemble is gay and not drearily monotonous as I thought it would be. I also thought that given your conception of a house, you were addressing yourself to a certain French elite rather than to the working classes. That is why your ‘villa’ type will succeed more readily than the ‘cité.’”20 It may not have been the total adulation Le Corbusier wanted—people from the Swiss Jura were not known to mince words—but the trenchant analysis from a fellow sufferer and escapee of La Chaux-de-Fonds moved Le Corbusier greatly.

7

At the same time that he was making houses for factory workers, Le Corbusier completed one of his most impressive private villas to date—the Maison Cook in Boulogne-sur-Seine, a suburb just at the edge of Paris. With this bold and handsome house, the architect took the flat face of a basic La Chaux-de-Fonds apartment dwelling—honoring the line of the street it parallels, providing shelter within a dense urban setting—and gave it tensile elegance, lightness, and esprit.

Working as a team, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret realized the five salient points that were the goals of their new architecture. Foremost, the Maison Cook was built on pilotis: simple, untapered columns that elevate most of the structure above the ground, so that the level one floor up is where the house begins. In romantic voice, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret wrote, in a jointly signed text, “The house on posts! Reinforced cement gives us the posts. Now the house is up in the air, off the ground; the garden passes under the house, the garden is also above the house, on the roof.”21 The goal was increased awareness of the earth itself, as well as of the sky and sun; these pilotis invited a closer rapport to what is natural, universal, and timeless.

That roof garden addressed the second of the five objectives. Again, the architect cousins were focused on the use of new technology to celebrate the glories of eternal nature: “Sand covered with heavy cement tiles, with wide joints seeded with grass, rainwater filtered through terrace gardens that were opulent: flowers, bushes and trees, lawn.”22

Inside the house, there was a third innovation: the free plan. Reinforced concrete eliminated the need for each story to be divided in accord with what was below, allowing the architects “rigorous use of each centimeter. Great economy of money.”23

The fourth great leap was evident in the long window band, of the type already seen in Ozenfant’s studio and La Petite Maison, realized here in two handsome stripes, one on top of the other. Point five was “the free facade,” which was feasible now that “the facades are no more than light membranes of dividing walls or of windows.”24

William Cook, an American journalist of independent wealth, was a friend of the Steins—Gertrude, Michael, and other members of that family of adventurous arts patrons who had come from San Francisco and settled in Paris. Cook was interested in the avant-garde and gave the architects unprecedented freedom. “We are no longer paralyzed,” rhapsodized Le Corbusier. Of the Maison Cook, he declared, “The classical plan is reversed; the area underneath the house is free. The reception area is at the top of the house. One exits directly onto the roof-garden, which overlooks the vast groves of the Bois de Boulogne; one is no longer in Paris, one seems to be in the country.”25

In his own life, Le Corbusier was content to walk the narrow streets and lively boulevards of the sixth and seventh arrondissements between office and home and climb the seven flights of the oval spiral staircase to the nest where, through the mansard windows, he and Yvonne could look at treetops and historic gardens. But in his work for a wealthy and adventurous client, he made architecture without historical precedent in its unadorned geometric pleasures, the sheer élan of thin pilotis supporting a noble mass, and the tactile delights of glass and steel and white concrete arranged to facilitate transparency and opacity so as to reveal, in an urban setting, some of those marvels to which his late father had led him on mountaintops.

8

On March 31, even though they were living in the same couple of rooms, Le Corbusier wrote his mistress a highly official letter with instructions to guard it carefully. For this document, he used her full name, “Mademoiselle Yvonne (Jeanne Victorine) Gallis.” As if addressing a docile schoolgirl, he told her that as her Easter present he had opened a bank account on her behalf.

Le Corbusier spelled out to Yvonne the terms of the account. The money he was to deposit would belong to her, but the account was to be managed by Jean-Pierre de Montmollin, and she could touch the funds only with his agreement. To prevent her from spending this money, Le Corbusier had instructed de Montmollin to keep the funds in “deeds” rather than cash; the reason for the account was that he wanted her taken care of in case something ever happened to him. One never knows what will occur in life, Le Corbusier cautioned.

With his usual meticulousness, the architect instructed his mistress which entrance to use for the branch of the Crédit Commercial de France on the Champs-Elysées. He also gave her the phone number of the bank. She was to meet with de Montmollin there. But “you are hereby informed that the shares of this account cannot serve to buy trifles, but to be useful to you, truly useful when the time comes.”26 He was starting it with a deposit of 2,500 francs—which had a buying power of roughly $2,245 today—to which he planned to continue to make additions, gradually but well into the future.

With Yvonne at a masked ball, late 1920s

HE WAS his mother’s caretaker as well, though Marie Jeanneret was doing her best to cope with her solitude in the lakeside villa. Le Corbusier counseled her to be strong, not to cry too much, and to see friends. Addressing “Ma chère petite Maman” two months after Georges’s death, he wrote, “I think so often of dear, gentle Papa and his last childlike voice, so faint, so charming. Our good Papa.”27

He and Albert and de Montmollin visited Marie at the start of April. Afterward, he advised by postcard, “Happy to keep with me the young, ardent, intelligent memory of you. Sustain your mission among us, the disinterested love of beautiful things.”28 For the rest of her life, which was nearly the rest of his, Le Corbusier obsessed over his mother’s youthfulness. He followed the postcard with a letter: “Ma petite maman, you must not say you feel like an old woman. You never wanted to be such a thing and you have been able to keep yourself young. So, no moral capitulations now. You are strikingly youthful. You delight me each time I see you, so apt to respond with generosity and enthusiasm. It is the proof you have never closed your heart or your mind. It is a joy for us to find you thus.”29 To remain fit and healthy, she had to stay active, accept social invitations, and, he instructed, resume her teaching, even if it meant giving piano lessons free of charge.

Edouard had assigned himself the position of family sage. He reported on a recent evening at Albert and Lotti’s villa in Autheuil: “Madame is very well, and very affectionate with Albert, to whom she gives evident signs of esteem. It is true that Albert is kind, lovable, and affectionate. He seems to have inherited the best of his father and his mother.”30

By that spring, Marie had met Yvonne. Soon after his father’s death, Edouard had begun to mention his living companion, describing her as a good but fragile soul, pure of heart but also at the edge of being out of control. The first encounter went well enough, but it would be an uphill battle for his mother to accept his unlikely choice. Le Corbusier did his utmost, writing, “Little Yvonne tends on the mantelpiece, under Papa’s photographs, a little altar covered with fresh flowers. Today they are wallflowers and lilies-of-the-valley. This mantelpiece covered with all of Yvonne’s souvenirs and knickknacks is a touching index of her taste and sensibility; she keeps an affectionate and respectful memory of you.”31

SENDING HIS MOTHER a long letter every four or five days, he began to act as if they were one big family: “Try, Petite Maman, to live this solitary life of yours stoically and serenely. We don’t forget you for a moment.”32 Then he told her about a dream that he said had lasted the entire night and was haunting him. In it, she was anxious and too thin. As if to relieve that worried state in which he saw her when he slept, he informed her that he was trying to help people he knew buy property adjacent to hers, so as to protect the neighborhood.

The architect implored his mother to write down, on a daily basis, all that was happening in her mind and heart, and to send it to him at the end of each week. “I think of you often,” he wrote, “realizing with true anguish how alone you are…. Your letters are so alive. We preserve an image of you as someone young and lively, strong in your faith. The sweet memory of papa prevails, a true poem in our emotional life, and there you are, so eager beside him, inseparable from him, purified by him; how eager you are to live, to know, to act, to love. I want you to realize that there is no barrier separating us, we are on the same footing, and there is no difference in nature or quality between us, save to your advantage. And so you are with us, the friend, the good comrade, in complete and mutual trust.”33

9

In May 1926, in Neuilly, Le Corbusier found a dog for his mother. “The puppy mutt, a thoroughbred police dog, is very likely to become another Jeanneret,” he wrote.34 His spirits were high. Important clients—American, English, and French—were pursuing him; he felt a sense of wind in his sails and of doors opening. (The clichés are his.) The novelist Colette told him she wanted to live in a “Corbusiere”—a term of her invention. They had dined together; Colette was, he told his mother, “an extremely captivating woman with magnificent eyes, painted from head to foot, and very garçon; she knows admirably—just like a cat—how to furnish a house which is a box of goodies.”35

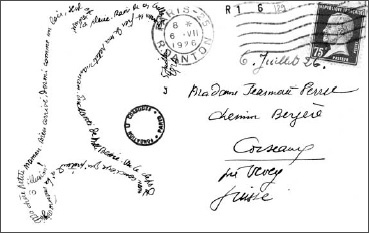

Dog formed by words in a letter to his mother, July 5, 1926

Le Corbusier lectured in Brussels about the Plan Voisin, reporting to his mother, “I was swimming like a fish in water, very much at my ease, even brilliant(!).” He let her know that, at a subsequent dinner for forty people in his honor, six speakers sang his praises. But what counted most was that when he was projecting images of La Petite Maison to his audience, he was overcome by visions of “dear Papa. Poor Papa!” And now, back in Paris, where he was writing the report from his bed, the thirty-eight-year-old Le Corbusier told his mother, “my first thought was for you.”36

10

When he was not boasting, Le Corbusier approached his success with a sense of measure. The princess of Polignac and the Michael Steins had come to the office about major projects, his Almanac of Modern Architecture was about to be in the bookstores, and he was making a film on urbanism, but “at the heart of this tumultuous existence, I persist in my pictures with stubbornness and fatalism. A lot of clients come to us now from high society as well as from the aristocracy of industry. It’s like a sudden launching. Of course, after such hopes there is always the counterattack of adversity; the franc is collapsing and the rising cost of houses makes chaos of our budgetary forecasts.”37

To demonstrate his rise to fame, the architect enclosed news clippings for his mother, but he singled out one that had appeared in the obscure Revue des Jeunes, claiming to Marie that it was the very first time he had been moved by something written about him. For the text in this magazine intended for young people acknowledged Le Corbusier’s work as “une affaire de Coeur. As always, everyone finds me the pitiless rationalist, the sectarian: here I am considered, above all, a man, and I am happy for that.”38

He was also still a vulnerable little boy. Le Corbusier closed this letter, “There, Ma Petite Maman. My eyes are burning, the light hurts me and the white paper is blinding. So, beddy-bye. Beddy-bye and kisses from your son, Edouard.”39

11

At the end of May, Le Corbusier wrote his mother about the sixty houses that were nearly finished at Pessac: “As I told you, setting modesty aside, I am astonished myself. Astonished to witness an absolutely new, unheralded architectural phenomenon, not bizarre yet telling us that things have changed, that there is a new spirit—here is a manifestation of that new spirit.”40 He was anticipating the official opening with feverish excitement. Le Corbusier, Pierre, and Anatole de Monzie, the French minister of beaux arts, were to go from Paris in de Monzie’s personal train car. Henri Frugès was ecstatic that the minister would be visiting his home territory.

Albert would be there as well—all that was needed was for his mother to make the trip, too. Le Corbusier urged her, “You don’t know the really beautiful countries. Switzerland is not a beautiful country.”41 Travel, he explained, was no longer a big deal; his one regret was that his father, who had studied geography so avidly and would have loved to see more places, had been denied the chance. Le Corbusier was determined to provide that opportunity to La Petite Maman.

Marie Jeanneret did not make the trip, but he described to her the event on June 13: “The mood was gay, free, unembarrassed, and one might say that the heart was in everything. The minister, Frugès, we ourselves, all of us were disinterested, pursuing only a dream of life’s improvement.”42 The opening was packed with journalists and filmed for the news reports shown in the cinema. After the official speeches, Le Corbusier gave interviews.

What he had created on the outskirts of Bordeaux had the joy of the event. “The color of the walls, a procedure never yet employed, was a kind of universal festivity, and the brilliant white set off the pinks—the greens, the browns, the blues; a unity of detail in everything, a tireless variety everywhere. The big cars are in the new streets. Leaning over the banisters, climbing up and down stairs, silhouetted against the sky, a crowd occupies the roof terraces over which spill geraniums, fuchsias, bushes and clumps of reeds.”43

The crowd on the vegetation-covered terrace was 150 people standing on the deck of the model house of Pessac, where the pine and chestnut trees surrounding the structure made the perfect backdrop to the new architecture. Everything was in place: artistic and natural beauty, the poetry of life, human generosity. Henri Frugès gave “a splendid speech, eloquent, actually ardent, setting forth his program of altruism…. I explain how we set about working, a technical speech, actually…and finish up by claiming the right to a certain lyricism, instancing the poetry of our creation.”44

The sun was shining brightly when the minister then told the audience that he had read Toward a New Architecture. Le Corbusier could not hide his pride from his mother. At dinner afterward, in Frugès’s house, Le Corbusier was seated next to de Monzie, and they spoke like close friends. He and Pierre went back to Paris with the minister in his “wagon salon” and slept like babies.

It was all a dream, wonderful to experience and even more marvelous to recount to the person who had given him life and raised him: “It’s so you can have your own little celebration, Petite Maman; after all, you have the true soul of an architect, and weren’t you the first to know how to live in a Corbusier house?”45

That the buildings had not received the necessary permits and that nothing could actually be inhabited was beside the point.

12

In early July, on one of the many trips he took to Vevey in the months following his father’s death, Le Corbusier wrote Yvonne during a free moment while walking the puppy, now named Bessie. “DD” told his “Petit Vonvon,” in a voice of unblemished contentment, “I’m walking this little mutt and waiting for her to do her pipi. She’s a handsome brute with a very becoming sky-blue leash. A boatman’s dog.”46

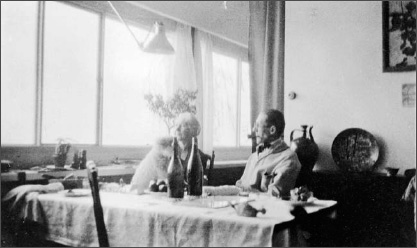

With his mother in the Villa Le Lac, late 1920s

The dog was easier than his human intimates. His mother was insistent that he stay on with her longer than he intended, while Yvonne was impatient for him to get back to Paris. He was also having problems with Albert, who had asked their mother for money. Edouard assured Marie that he had become directly involved in his brother’s latest professional endeavors, so she need not worry about his request. “I won’t forget about Albert, but I’ll deal with him discreetly—though actively,” he wrote pompously once he had returned to France. Then, to assure her of his own financial well-being, he boasted, “As for me, we have the king’s court around here. It’s becoming a client a day, all over the place.”47 If he could not hope to rival his brother as their mother’s preferred son and fellow musician, at least he could take the upper hand as a breadwinner.

ALBERT WAS NEEDIER, but, unlike Edouard, did not instruct or challenge his mother. Le Corbusier might conquer the world of architecture, but he never achieved his goal of upstaging his brother as Marie’s favorite. The architect perpetually barraged her with news clippings about the giant he had become and emphasized his role as her protector, but the widow now had an issue she considered more pressing. The villa in Vevey had water leaking into the living room; if he was such a great architect, surely he could solve the problem.

MARIE JEANNERET was, in addition, tormented by fears about her household expenses. She could not fathom the costs she was incurring for water and gas at La Petite Maison. Le Corbusier angrily reminded his mother that she had the same income as when his father had been alive and that she used to mock Georges for his worries about money. He blamed her for torturing herself. He felt punished—as if she still held him accountable for the disaster of the Maison Blanche.

Again he informed Marie that he was working like someone possessed, pushing himself until midnight every day, including Sundays. And for all that he was doing in the world, he was occupying himself with her issues and taking care of Albert. He lectured his mother:

Petite Maman, be careful, keep your wits about you. Don’t make mountains out of molehills. Try to find a purpose in your day, recognize what’s important and what’s secondary. And always remember that forty percent of what the mind undertakes or what one actually does must fall through. So don’t cry “wolf.”…

You’re making me write this morning so that my letter will reach you without delay. But you’re not getting the best of it, for I’m tense and nervous—I know I have other things to do. But of course since you’re ma petite Maman I have written and I’m glad to do so; but it’s not much of a letter—more of a porcupine. Your Sonny gives you a big hug, Ed.48

To please Marie Charlotte Amélie Jeanneret-Perret remained his greatest challenge.

13

In August 1926, Le Corbusier learned to swim. He had allowed himself and Yvonne the luxury of a vacation in the holiday town of Le Piquey, near the large Bay of Arcachon. In this first summer after his father’s death, the warm weather and sunshine at the edge of the sea were a great comfort. He wrote his mother, “It takes an hour and a half to cross the pine forest to reach the ocean. Site of a simple majesty, a tremendous beach stretching in a straight line over a good deal of the coast from the Gulf of Gascony. The ocean is protected by a wide ribbon of dunes at the edge of the fields, the sand entirely sown with yellow immortelles, shifting like the sands of the desert. Then the pine groves begin, sometimes tall trunks, sometimes low bushes; a warm and intense smell of resin, of turpentine, and above it all, relentlessly, a burning sun, making the sand hot and the shade cool. A constant breeze keeps the temperature mild all day long. O deadly Paris! Here the pure sand everywhere, clean hands, clean feet, clean clothes. O filthy Paris!”49

With Pierre Jeanneret at Le Piquey, late 1920s

He had read a newspaper article that represented Switzerland as the equivalent of Siberia. Driving home the contrast from his seaside Eden, he continued, “Here we’ve had nothing but an implacable sun, but all very magnificent and welcome. I find a certain humor in thinking of you fussing in your twelve square yards of garden and knowing you’re quite happy doing so while we have these vast spaces of pine forests and the ocean.”50 He could have chosen to point out the oceanic nature of Lac Leman—that small garden faced what looked like a sea—but something in Le Corbusier was tortured.

One of the issues was Pessac, where he attributed the failure to hook up water to be a result of politics: “All this time the ministers administered, doing so in their very bourgeois way in order to keep up the spirits of the money-lenders who quite patriotically had invested, most of it abroad. Poincaré [Raymond Poincaré, the French prime minister at the time] is not my hero, far from it; a man of the conservatives, of the bourgeois, against whom we struggle every day. But of course, the money is with the bourgeois, therefore the bourgeois must be saved.”51

Le Corbusier was determined to release himself from anything he considered bourgeois, too focused on money, or Swiss. He wrote his Calvinist parent, “In the last ten days…nobody has done anything at all. I haven’t read a line nor done a stitch of work. But I’ve learned to swim very well, and yesterday across the dunes and the woods I made an excursion quite flattering for my age: I went to the ocean with Pierre, running all the way without stopping once: 24 minutes going, 28 coming back, a distance considerably greater than from La Chaux-de-F. to Le Locle (roundtrip) (9km).”52

One detail of the holiday he left out was the presence of Yvonne. Marie certainly knew she was there, but Edouard still wanted his widowed mother picturing him alone.

14

Le Corbusier wrote his mother about a book he had been reading by René Allendy, a pioneer of psychoanalysis in France. Born in Paris in 1889, Allendy specialized in dream interpretation and issues of sexuality. Le Corbusier reflected, “Everywhere a generalized movement appears in favor of the mind and exclusive of a narrow materialism. The former does not operate without the latter. I often experience this and often I am accused by some of a terrible rationalism, by others of being a dreamer and an aesthete. Yet architecture lives on relations which are a quivering lyre exclusive of practical conditions and techniques of the problem: ‘touch me, touch me not,’ everything is there. That’s all there is to it, art is here or is not. I am moved, I am not moved. And to concern oneself with things that provoke emotion is one of the rare felicities of living, and it’s because we concern ourselves with such things as these that we are happier than the rest, exclusive of material conditions.”

In this confused exegesis on the balance between the emotional and the practical, Le Corbusier went on to say that his father was “permanently and constantly present: he is here, you know he is.” He allowed, “My regrets, my sadnesses are constantly happy. I think: if Papa were here.” He contemplated the joy Georges, “a man who passionately imagined the earthly paradises he divined elsewhere than in that severe and wretched Jurassic trench,” would have known if only he had seen the places where his younger son now traveled and worked.53

The seacoast and the precinct of art both belonged to the sacred realm of feeling that his father had recognized as one of life’s goals, however elusive and difficult it might be to achieve.

15

Returning from his halcyon holiday, Le Corbusier remained overwhelmed by thoughts of the man who had died eight months earlier. The architect wrote his mother, “Yesterday morning between Nevers and Paris his last image haunted me continuously. Moreover I kept looking at my hands shrunken by the physical activity of this vacation, and they were a little like Papa’s hands. Of Papa I keep the throbbing image of those last days, of the day when I realized, precisely a year ago, that he would be leaving us…. That magnificent image at his death which is engraved all the deeper because I could see it so clearly in my drawing of him and then keep it in mind. That image which gives me courage for the future because I have felt the nature of the blood that flows through me so that in this dray-horse life we lead—and this jackals’ life, this life of hyenas and wolves, I realize very clearly that I belong to one side and not the other, and referring myself to the testimony of our origins—our father, our mother—I move ahead, tranquil and calm, seeking one thing and not the other. You write so nicely, your letters are so true, you are so young, so frank, that I am entirely happy reading you, feeling how strong you are, how healthy in mind and body. When you write you are yourself. Your identity is complete, externals vanish. Then it is extremely comforting for a son to feel his Maman leaning over his desk in your little family dream and to know that his Papa is lying in peace, hands crossed over his chest, under the cypresses of the hill at Saint Martin. My dearest Maman, an affectionate kiss from your Ed. And to Bessie—show her my photograph so she can absorb it, you know how much I love the little creature.”54

Now more than ever, he yearned for his mother to be happy and was desperate that she not feel constrained by the architecture of La Petite Maison or by her own mania for neatness: “It’s you who makes that house alive. Knowing how to arrange each thing so that it becomes animated by a certain grace.”55 He had designed La Petite Maison to give her joy, not to impose a way of life, and to make household maintenance and daily chores as easy as possible. Le Corbusier’s goals for his mother became his dream for all domestic design.

It therefore stung hard when Marie Jeanneret and Albert forgot Le Corbusier’s thirty-ninth birthday. Three days after the fact, once he was sure there was no greeting that had been delayed by the post, he wrote his mother, “It hasn’t happened to me since I was 16, when Papa told me: ‘Now you’re too big a boy.’ Tender kisses from your Ed.”56 Without specifically mentioning Marie’s oversight, he let her know that his Aunt Marguerite, a distant relative, had sent a card, and he had received flowers and a new pipe from unnamed sources.

This was the first October 6 since his father’s death, and now his mother was happily ensconced in the small family house with her preferred child. It was more than Le Corbusier could bear.

MARIE’S DISTRACTION was understandable; Albert was having a form of psychological breakdown. In treatment with the same Dr. Allendy whose theories Le Corbusier had been reading, he had left his wife and her children in Paris and retreated to the family house, where he was mainly making music by clanking rods against bizarre arrangements of drinking glasses he had suspended upside down from strings.

Le Corbusier was forced to assume responsibility for the music school Albert had started in Paris. As he made clear to his mother several weeks after the birthday episode, he was now busier than ever before as an architect and painter of international importance. He framed his recitations of his own successes as if they were intended primarily to reassure her that at least one of her children was functioning well, but he relished his exalted position while Albert was floundering.

In spite of the birthday slight, Edouard now also sent his mother two samples of cloth and a fur collar for a coat—and he constantly inquired about the dog he had given her. Surely she must see that he had become the good child.

16

At the end of October, a new German edition of Toward a New Architecture sold out instantly. The success made Le Corbusier even more manic. As the hours of daylight decreased with the onset of autumn, he wrote his mother, “The day is wretchedly short of hours. And the hours themselves are even shorter. Ideas attack from all sides. I must achieve, I must act; so it’s a kind of frenzy of work and an avaricious use of each minute. Now that the galley seems launched, everything begins to open up and multiply.” He was, he told her, engaged in “a crushing labor.”57

Nonetheless, he would bring the design for his father’s tomb when he visited in a few weeks. He wrote, “I think of you in your tiny house, busily doing everything for everyone and often think of our Papa on this anniversary of his last sickness when it finished him off. What anguish we had last year at this time. And how a capital event intervenes in life, suddenly changing everything! And how, too, a man can straighten up and pursue his destiny all the same, a destiny quite unknown and ineffable. Tomorrow? What will happen tomorrow? There is the tomorrow we prepare for quite logically. And the other one, unknown, otherwise determined, which may suddenly intervene.”58

Le Corbusier was desperate for his mother to attend a lecture he was giving in Zurich. He spelled out the details: “Take a ticket for Zurich, straight to Vevey. My lectures are at Zurich on the 24th and 25th, so get one combined ticket for La Chaux–Zurich–Vevey. I’ll pay the difference for La Chaux–return. So it’s all arranged.”59

For once, she managed a trip. Afterward, he wrote, “You may not imagine how happy I was to be with you in Zurich and of course I was so happy that my second lecture went off well and you had nothing to blush for. I was very touched by the testimonials of respect and sympathy which you provoked. Your attitude and your lovely expression of Corbusier’s old mother made respect flourish all around you.”60

Recognition was coming at last. By the end of the year, Le Corbusier was informed by Josef Hoffmann, the man who had once been too busy to see him, that he had been named a “membre correspondant” of the Bund Österreichischer Architekten.61 It was a major honor from an organization that included among its founders Klimt, Otto Wagner, and Karl Moser—even if these were the same Viennese masters whose work he had always loathed.

The future was assured: “For us, the painful hours have passed, there remains no more than what is agreeable: to make sure that it is beautiful.”62 There was no question who the “us” was: Le Corbusier and his widowed mother.