XXV

1

In 1927, Charlotte Perriand was a lively, svelte, flapperesque woman of twenty-four. She had a peaches-and-cream complexion, and her smile revealed a flash of pearly white teeth. Everything about her bespoke confidence and flair.

In 1925 Perriand, who was a student of design, saw the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau. It opened her eyes to modernism. The following year, she left her parents’ traditional middle-class Right Bank apartment for a new life. She married an Englishman, rented an old photographic studio looking out on Saint Sulpice, danced the Charleston, and marveled at “a stark naked black Josephine [Baker], her little ass embellished with a string of bananas, dancing to a wild rhythm—an authentic femme sauvage.”1

Determinedly adventurous, Perriand bobbed her straight, shining hair and wore a necklace of chrome-plated brass balls. She made her Bar sous le Toit—a daring, minimalist glass-topped unit on a truncated I-beam with a glistening nickel front—which was a hit at the 1927 Salon d’Automne. She became confident of her talent, but was unsure of what to do next.

Having read Le Corbusier’s books, Perriand decided to storm the architect’s headquarters unannounced. It was morning, however. Le Corbusier, as usual, was not there; he was at home, painting and designing. Pierre Jeanneret, who received her at the door, was cordial, but Perriand refused to state her case to anyone but Le Corbusier himself. That afternoon, she showed up again without an appointment, now with a portfolio of drawings under her arm. She was duly intimidated by Le Corbusier, forbidding behind his large glasses, but Perriand had moxie; when the master asked her what she wanted, she replied, “To work with you.”2

The architect took a quick look at the fetching young woman’s drawings. “We don’t embroider pillows here,” he snapped. He showed her the door. On her way out, Perriand told him about the exhibit at the Salon d’Automne and left her card. The next day, Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret visited her stand at the salon and then wrote to offer Perriand a job.

When she excitedly told a professional acquaintance that she was going to work for Le Corbusier, he warned her not to. She would dry up, the friend insisted; to take a job in Le Corbusier’s office meant becoming a drone. She never forgot the warning, but for the next ten years Charlotte Perriand remained an employee at 35 rue de Sèvres.

PERRIAND was ignited by the intense engagement of everyone in the office: “Think of that heroic period, pioneering and penniless, with access to so few resources, think of all those projects of architecture or urbanism never to be realized yet so carefully studied and planned,…projects in relation to humanity…. To create the human nest as well as the tree that would bear it. We ended by believing in it all. Enthusiastic young men from the best schools the world over came here, not only for architecture but for Le Corbusier, for his way of reconsidering all problems, for his aura.”3

Perriand’s first task as an employee was to help with furniture and revisions to the interior for the Villa La Roche, which had been begun four years earlier. Combining the concepts of Vitruvius with the latest technological advances, she, Pierre Jeanneret, and Le Corbusier worked in tandem to create seating and tables and the other necessities of comfortable living. Le Corbusier had long dabbled in apartment furnishings, but now he wanted revolution inside the house as well as outside—furniture as technically and aesthetically streamlined as his architecture.

2

Tubular steel had been introduced into furniture design in 1925 at the Bauhaus. The team at 35 rue de Sèvres worked on armchairs, chaise longues, and other pieces that employed this lightweight, tough tubing that had been invented for the construction of bicycles. At nightfall, Le Corbusier evaluated their progress. He was mocking and scurrilous, mainly in his insistence that the scale was all wrong. Perriand decided that she should make full-scale prototypes of the new pieces. She went to the enormous hardware store BHV to buy rivets and just the right springs for suspending the support of a chaise longue, got her locksmith to construct the steel frames, and located a saddlemaker who sewed hides in the style that had been perfected by the luxury saddlemaker Hermès. She used English leather, considered the best in the world, for armchair upholstery, and had cushions made with the finest goose-feather filling. With the same artisans who helped her create the Bar sous le Toit, she completed the assembly.

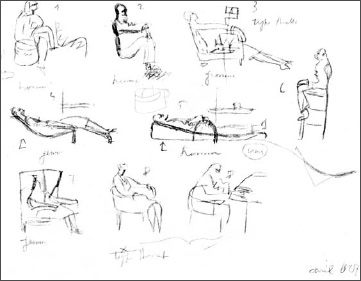

Drawing of different ways of sitting, ca. 1928

Perriand then invited her two colleagues to her studio, without mentioning that she had been making these prototypes. In that light-filled space facing the great church of Saint Sulpice, Le Corbusier and Pierre lowered their backs into the curves of the “chaise longue de grand repos” and stretched out their legs. They sat at attention in the visitor’s chair and let the boxy armchair cradle them. “Very smart,” Le Corbusier allowed.4 The designs were ready to be built for the Villa La Roche and the interiors of his new buildings.

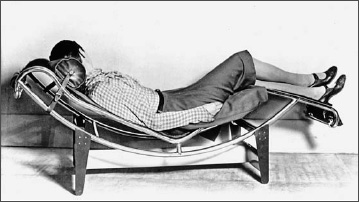

THE MOST INVITING, soothing, yet energetic of the threesome’s seating designs was the chaise longue. Here a tubular-steel support—like a cartoon of an entire human body—is suspended above a sweeping curve. It reads like a drawing as much as a piece of furniture, as if the form of the frame had been scribed in the air. The open-armed curve of the heavy black stand underneath the seating element seems to cradle it warmly.

The chaise is a jazz-age piece of furniture—as fresh and of the epoch as Perriand’s bobbed hair and the dashing window bands of the Villa La Roche. A thick pony-skin covering cossets most of the user’s body, while a leather-covered cylinder cushions the neck and head. That black-and-white covering suggests the sleek speed of its source, galloping on slender, piloti-like legs. The rolling shapes invite you to sprawl and to take pleasure, to put up your feet, lean back, and feel succored. Meant for open spaces like those in Le Corbusier’s residences, it conjures his insistence to his parents that they take it easy in life and enjoy what they have (see color plate 3).

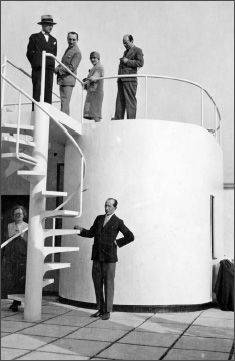

LEFT TO RIGHT: Le Corbusier, Percy Scholefield (Charlotte Perriand’s first husband), Charlotte Perriand, Georges D. Bourgeois, and Jean Fouquet at the Salon d’Automne, Paris, 1922. Photo by Pierre Jeanneret

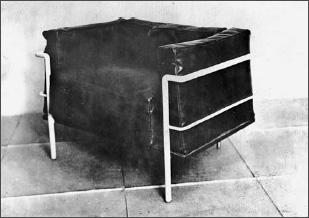

The visitor’s chair has a simple tubular frame, armrests that resemble automobile fan belts, a minimal but comfortable seat, and an adjustable back made of stretched pony skin. Its lean form encourages a perfect mix of ease and alertness. The cubic club chair depends on its tubular-steel frame to support thick, tightly packed, leather-covered blocks that surround the user like a womb. Like Le Corbusier’s architecture, this chair is a basic box form, based on the simplest vocabulary, that functions as a stage for human living. All of the pieces have the boldness, the balance of the tensile and massive, and the playful rhythms of Le Corbusier’s houses.

Charlotte Perriand resting on the LC4 Lounge Chair

Club Chair, 1928

IT WAS A WHILE before the new furniture found its audience. One of the places where Le Corbusier hoped the chairs, as well as some new tables, would go was the villa he was completing at Garches, but the owners chose to keep their Renaissance tables and eighteenth-century armchairs. In 1929, however, Le Corbusier and his team showed the pieces at the Salon d’Automne. It was the beginning of the slow acceptance and manufacture of these objects that today grace homes and offices throughout the world.

3

In 1906, Pablo Picasso painted a portrait of Gertrude Stein in which the writer appears physically massive and indubitably confident. The villa Le Corbusier completed in the Paris suburb of Garches in 1927 for Gertrude Stein’s brother Michael and his wife, Sarah, has the same daunting, uncompromising presence.

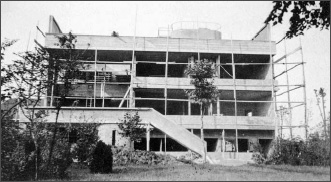

The Steins commissioned it with their close friend Gabrielle de Monzie, formerly married to Anatole de Monzie. Even more assured than the Villa Cook, the facade of the villa at Garches (also called Villa Stein and Villa de Monzie) makes bold declarations. The entrance, with its cantilevered overhang, beckons us in; the garage announces the role of the automobile in the lives of the inhabitants; the lithe window bands suggest an interior full of daylight; and the large rooftop balcony invites communion with the sky.

Villa Stein–de Monzie in Garches, during construction, 1927–1928

That white block at Garches, set back from the road like a light-footed giant in its lair, is an exemplar of the tenets of Purism. So is its lesser-known garden facade. Graced by the strong diagonal of an exterior staircase and a dashing plane of pure luminous blue for the exterior ceiling created by the roof slab over a terrace, the back of the villa is an abstract composition on a par with the greatest inventions of the painters who were pushing nonobjective art to new peaks at this same wonderful moment in the history of art.

Villa Stein–de Monzie in Garches, front facade, 1928

Le Corbusier achieved those aesthetic strides by taking substances of enormous weight and rendering them ethereal. The rigid steel joists and mullions and the solid concrete walls all appear to float. What Le Corbusier has done with physical substances, he has also done with emotions. He has cloaked his own doubts and trepidations to evoke a look of positive force. With its noble design and exact proportions, Garches is unequivocally triumphant.

El Lissitzky (second from left on top), Mondrian (standing below, with his hand on the stairs), and other visitors to the Villa Stein–de Monzie, late 1920s

The man who had grown up in a world of Calvinist denial—who remained beset by anxiety—had found the means to evoke the ebullience and certitude that were his ideals. All that remained necessary was for his mother to picture it. He boasted to her that Garches was “a masterpiece of purity, elegance and science.” This was because the three clients were “the best we have had, having a carefully established program, many requirements, but these being satisfied, having a total respect for the artist, or better still, being people who know what an artist’s sensibility consists of and how much can be gained from it if it is well treated. These are the people who bought the first Matisses, and they seem to consider that their contact with Le Corbusier is also a special moment of their lives.”5

In Le Corbusier’s encomium for his clients at Garches, he described a conflict with their predecessor Cook, with himself as the Buddha of the tale: “[Cook] had fallen victim to a raging neurasthenia, stubbornly supposing that I am completely indifferent to him. We exchanged the most unpleasant words, I with glacial calm. Finally, in the face of the idiocy of such an attitude I offered peace, and now he is, in his own words, serene as an angel, a confirmation of my ideas about the misunderstandings which so stupidly manage to make enemies. Often with a well-placed word one can mend a disastrous situation.”6 No one else, of course, would have agreed with Le Corbusier’s depiction of himself as the sage and diplomatic one.

Le Corbusier equated the purity and clear vision manifest in the splendid villa at Garches with the same traits in its owners. The man whom he referred to as “Le papa Stein” was on-site for hours every day. He observed everything but did not impose. Stein’s assuredness was manifest in the noble facade, the graceful windows and balconies: “The house is clean and pure, far beyond anything we have done: a kind of obvious, unarguable manifesto.” Le Corbusier clearly identified with the client: “Le papa Stein…against whom so many others struggle, denying and accusing.”7

Just as the villa was being completed, Le Corbusier gave another lecture on the Plan Voisin. “Here in the heart of Paris, with no preambles necessary; I had the impression that I could be direct, ardent, firm, convincing.”8 He and his architecture had the same unassailable confidence.

4

“Direct, ardent, firm” was how he was about Albert as well. He wrote his mother, “It’s our distinct impression that Albert was born lucky and that your continual apprehensions are entirely misplaced. I can assure you that my existence is in every way more difficult than Albert’s, and you must get out of the habit of ‘pitying’ him. He has been very lucky, period, that’s all there is to say.”9

Le Corbusier had no doubt of his right to praise or criticize in every realm, to design other people’s lives for them. When he didn’t chastise, he encouraged. He let his mother know that her letters were “indispensable…. They bring us a breath of youth, of joy, of limpidity, of courage. They show us that despite the fact that you are our Maman, you keep the same tempo as we do; they let us hope that perhaps like you we can remain among the young for a long time to come.”10

But she had to overcome her mania for housekeeping. When Marie fell in her basement, he issued a sharp reprimand: “It doesn’t surprise me, it was inevitable given the kind of frenzy that accompanies your domestic activities.”11 He begged her not to let her parsimony and fears about the cost of coal prevent her from keeping the house warm enough, especially since, if she became sick, she would not let anyone lend a helping hand.

Why must she live so frugally, given how many important people he knew? In October 1926, Le Corbusier had written that the duke of Württemberg had come to the rue Jacob to see his paintings; at the start of March 1927, he told her this a second time, as if the visit had just occurred. He described the grandson of the former archduke as “a young man, very refined, very gentle, tall as a grenadier, but with perfect manners. A king in exile. Actually I think he must find all this much more amusing than the throne.”12 If royalty preferred to be with him than to rule its kingdom, couldn’t his mother do a better job of appreciating her son?

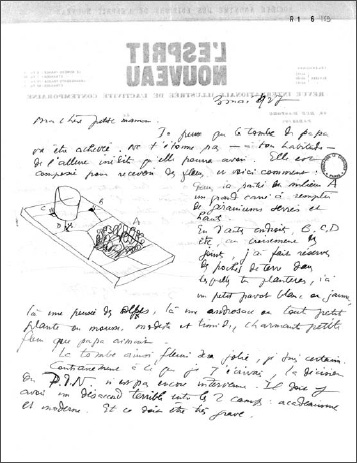

WHEN HE WAS NOT trying to redesign the world, Le Corbusier was revising the tomb for his father and planning the arrangement of its flowers. Like the trees on the patio at Garches, the blossoms were integral to the design. He gave his mother the task of organizing and maintaining the seasonal flowers meant to convey both the beauty and the fragility of life next to the modest but perfect monument housing the remains of the man Le Corbusier now regarded as a saint. He specified red geraniums, “a poppy of the Alps, a pansy, a saxifrage,” and some modest moss, his father’s favorite.13 He sent sketches to his mother to show her where each should go.

His father’s tomb, the life span of flowers, the new dog—all reflected his usual preoccupations: “Bessie has become the pretext for affective mental attitudes that are in reality destined for dear Papa. And yet life shows us how little we appreciate the time we have to live, which is constantly passing, ceaselessly concerned as we are with longing for what we don’t have and so careless about appreciating what we do. How many splendid hours we might have lived in peace and enthusiasm and joy.”14 Whether this was wistfulness over his own shortcomings or advice to his mother was unclear.

Le Corbusier had become “maniacal about my time. At each second, new ideas tempt me, absorb me…and the years pass, wildly, alas.” Fortunately, he had one constant: he kept a photograph of his mother on his desk. It stood behind his inkwell, facing him at all times. He wrote her, “I see you there often, believe me, looking just the way I most admire and respect you.”15 In letter after letter, he referred to this photo, saying it made him feel as if she were present and he was actually speaking to her. The most celebrated and disparaged architect in the world wanted his mother to know he thought of her perpetually.

Sketch of his father’s tomb in a letter to his mother, May 3, 1927

5

Le Corbusier continued to try to convince as many people as possible about the merits of the Plan Voisin. Even if, privately, he wanted it entertained only as a concept and not a fait accompli, he pushed forward his agenda of urbanism whenever he could. He lectured at the Bourse du Travail, an organization that helped people find jobs, and in March 1927 he met with Jacques Arthuys, a militant nationalist who, with Georges Valois, had founded Le Faisceau—the French fascist party. He wrote his mother, “The other day I was received by one of the two leaders of the Fascist Party. Arthuys. Received with open arms and much cordiality and yesterday I was sent a Fascist pamphlet of 60 pages ending with a chapter on the heart of Paris—on my version of it—with irrefutable developments and a clear proposition to appoint me minister of urbanism and housing. In short, you can bet your life I am not involving myself in politics. What saves me from any absurd or dangerous haste are my morning pictures, one each morning, where the confrontation is complete, the difficulty total, basic, overwhelming. Thus half the day I say the hell with everything and everybody and work out a problem whose solution does not exist, since it escapes with each step forward.”16 Now resigned to the idea that the League of Nations project was buried, this avoidance of political engagement and retreat to his own painting were his formula for personal balance.

In mid-March, Le Corbusier went to a masquerade party at Albert and Lotti’s to celebrate the birthday of Lotti’s daughter Brita. It furthered his sense of equilibrium. Albert was now back in Paris, having rejoined his wife and her daughter, and the event for the extended family at the Villa Jeanneret made his architecture serve its ideal function—as a setting for human joy and connectedness. “What must be acknowledged is people, things, events in their specific character,” he wrote, “and what must be properly valued is that diversity which is the very thing that makes life agreeable: that adds, that accumulates, that constitutes a certain capital of appreciation and measurement; that embellishes, that furnishes existence. This is the whole joy of life: to know how to open one’s eyes, to marvel, to recognize positive values, to bypass negative ones and not collide with them. Everyone lives among pluses and minuses. When we can respond to the pluses, that is happiness. That’s all there is to it.”17

Half a year later, however, Le Corbusier’s emotional pendulum was swinging in the other direction. “I ask for nothing more than sun, sun for God’s sake, by which to see clearly and be happy. Wretched winter which begins so cold!” he wrote his mother in November.18 He had played basketball with Albert, but most of life was pointless.

An event hosted by one of his publishers exemplified the silliness and pretentiousness all around him: “On Saturday I attended a great banquet given by Editions Crès on the occasion of their new building. The building? O publishers of Le Corbu! And the most stupefying asininities. There were three speeches, and one heard not a word, not one! That was a minor deficiency, and we giggled about it, but the whole phenomenon was a madness.”19

The more worldly “Le Corbu” was, the more he regressed as Charles-Edouard Jeanneret. He continued, “Dearest Maman, I am going beddie-bye with the following nighttime equipment: a flannel nightcap, a wool sweater. Stretched out on my back, immobile, above all not breathing. Make a note of it, dear Maman, that’s how you get rid of colds, but this one couldn’t be nipped in the bud the first night nor the next. In the train it assumed gigantic proportions. Affections from your Ed.”20

In her reply, his mother only groused about the heating system in Villa Le Lac: “Here only to return (but meeting Mme. Mathey at the station), I found a freezing house and since Le Corbusier had done nothing, I summoned the plumber to find out if I dared turn on the heat and whether nothing unfortunate had happened during my absence. This lasted a long time and when I could finally get a cup of hot coffee from my neighbors, I had reached the point where my teeth were chattering and my whole body shivering.” Having visited her cousin Marguerite in Zurich, she “decided not to leave the house during winter any more; it’s too risky and coming home too melancholy.” Her solace was the puppy: “Bessie is wonderful. I went to pick her up Monday and it was touching to see her transports of feeling…. I’m pretty certain now that she’s sterile, as Sara [another dog]was, and that there won’t be any consequences to her debauchery.”21

Marie Jeanneret was deeply concerned about her fragile Albert now that he was again helping with household tasks while trying to run a small music school, but she made no further comment or inquiry about the life of the son who had “done nothing” to correct the problem of her freezing house.

6

As winter settled in, Le Corbusier had a recurrent dream. His father was alive, but soon to die. Each time he had the dream, he woke up and had a brief moment of thinking it was reality. Afterward, fully conscious, he was struck by the idea, as if it were totally new, that only two years earlier Georges had still been drinking in the pleasures of life.22

The architect was assuming a paternal role to the painter André Bauchant, a talented “naïve” artist, somewhat along the lines of “Le Douanier” Rousseau, who asked Le Corbusier to be his executor for all of his paintings. Bauchant had recently begun to win prizes and commissions, but even now, the artist explained, his parents, friends, and everyone else laughed at him. Le Corbusier was the sole person who might do justice to his work after his death and who had the aesthetic judgment as well as the financial acumen to sell his paintings for the best value, thus to assure the well-being of Bauchant’s wife, who suffered from cerebral amnesia. Le Corbusier was touched by this confidence from an artist who exemplified innocence and rare truthfulness and was “animated by an extraordinary fire.” On December 17, they signed their contract. It was another moment when Le Corbusier felt he had found the balance that made it possible to survive life’s defeats and the ultimate reality of death; he wrote his mother that Bauchant was the exemplar of the Jeanneret family motto: “The moral: do what one must without flinching. Neither fame nor blame has anything to do with it. Believe in what one is doing and do it well.”23

Pierre Jeanneret, André Bauchant, Yvonne, and Le Corbusier standing with a painting by Bauchant of the four of them, early 1930s

7

The League of Nations debate resumed at the start of the new year. Le Corbusier’s scheme still had its ardent partisans, with journalists and even some of the jury members entering the fray.

In February 1928, Frantz Jourdain declared the treatment of Le Corbusier’s design “a second Dreyfus Affair.”24 The comparison to such a monumental incident of prejudice and scapegoating was especially startling given Jourdain’s stature. This champion of modernism, a friend of Emile Zola’s, had joined Zola’s fight against the brutal persecution of Alfred Dreyfus and its defenders. By invoking the name of the Jewish colonel, Jourdain was depicting Le Corbusier’s foes as the architect himself did: as the propagators of the vilest form of evil, deeply entrenched within the ruling establishment.

The outside support encouraged Le Corbusier and Pierre to write an appeal demanding that the Council of the League of Nations overturn the decision of the five-person jury. “There is a lot of wind in the sails. And also a lot of concealed withdrawal in my mind. The tête-à-tête is the great gain I have made in the last few year,” he wrote his mother in mid-February.25

Shifting back and forth between a hard-line aggressive approach and his insistent fatalism, the architect was resigned to letting the chips fall where they would. On March 3, he wrote Marie, “We have done the best we could with what was within our means. Now once again the imponderables will function. Conscience mollified by work well done, I await with a smile the coming yes or no. And I will not be discomfited if it is no. That will be the proof the thing is not yet ripe.”26

The warrior had again become a buddha. Or so he tried to convince himself, until an article called “Les idées de M. Le Corbusier. Maisons et Cités de demain” by Paul Bourquin appeared in two parts in L’Impartial, a daily newspaper in La Chaux-de-Fonds. Its content demolished Le Corbusier’s calm; there was no more feigning the equanimity he was trying to maintain over events in Geneva. This was one onslaught he could not bear, because it was read by his mother’s friends.

Bourquin began by accusing Le Corbusier of “certain distinctly communistic tendencies, an arrant materialism, the abolition of thought and the triumph of action. Everything is organized around these three concepts.” His take on Le Corbusier’s domestic architecture was: “Le Corbusier’s vision of the world manages to find a model of beauty in the humblest rabbit run. One trembles to think of the lot of the poor wretches condemned to live in such houses which a wicked joker once called—quite accurately moreover—suicide crates…the great specialty of the architect Le Corbusier whom the Germans seem to hold in special esteem are the thickly planted terraces, pergolas and verandas he lavishes everywhere. On one terrace I notice built-in Swedish gymnastic equipment; in one bathroom hangs a punching-bag. I shall not conceal from our eminent compatriot that certain of his inventions have somewhat astounded me. Why for example make the main entrance to a house through the cellar? As for those shoulder-high reinforced-concrete barriers separating the bedrooms, they seem to lack a certain intimacy.”27

Bourquin’s article followed the line of thinking put forward by Swiss architect Alexandre de Senger in an essay in Le Bulletin technique de la Suisse romande, which, in turn, had been picked up by the Gazette de Lausanne. De Senger’s text, which echoed the official reasons given for rejecting Le Corbusier’s League of Nations project, was yet another frontal attack: “Thus Le Corbusier—any polyphony wearies him, overwhelms him, exhausts him. He complains, ‘The moon is not round, the rainbow is a fragment, the network of veins in marble is disturbing, inhuman.’ Exasperated, he exclaims: ‘Nothing in nature attains the pure perfection of the humblest machine.’…And to escape this dreadful torment he adds: ‘Nature is geometrical.’ Architecture, too, diminishes, torments, maddens this exhausted man. Only the simplest forms such as cubes and prisms are available to his comprehension; he delights in them because they deliver him from the superabundance of nature. And Le Corbusier, who believes himself to be an architect at bottom, is merely a sectarian for whom any organic development is synonymous with disease.”28

Le Corbusier wrote the newspapers that these attacks were not simply a matter of aesthetic disagreement but were full of lies. He told his mother he was “in a violent rage” it was “a scandal, a dirty trick.” What upset him above all was the anguish this critique would bring her and Aunt Pauline, as well as the insult to his father’s memory. “Corbu is denounced as an element of disorder and materialism, as the negation of art, of thought,” he lamented. Switzerland itself had betrayed him: “Three years of struggle (committee, council, and general assembly of the League of Nations), and the details of this affair certainly represent for us the blackest, most desperate tribulation that can affect honest consciences. It was cruelty personified. From the beginning, the city of Geneva maintained a hostile atmosphere toward us.” But, Le Corbusier assured his mother, he was tough enough to survive it all. It was “a vehement and, I repeat, odiously dishonest attack. Apart from that, dear Maman, smiles all the way. Spring is coming, the weather is fine and everything else follows.”29

8

In 1928, an organization called the French Appeal was formed to try to convince the League of Nations jury to reverse itself and select Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret’s design, and the architects themselves published a pamphlet stating their case. Marie Jeanneret wrote Albert and Lotti, “Edouard tells me there is wind in his sails. What splendid optimism! But this morning, receiving the dignified communication from the President of the French Appeal from Jourdain, from Elie Faure, etc. etc…. I remain impressed and moved by the quantity and especially the quality of the signatures attached to the notion. What would our Papa say confronted with this admirable testimony of faith. He left us too soon! Sensitive as he had become to the consideration granted to his sons, this would have caused him, coming from such men, a sort of immeasurable joy. Alas! In spite of everything, I do not believe in the reversal of matters with regard to the Palais des Nations, and as with this hard Nennot [sic] Le Corbusier will seem strange to many. Who will yield, the young man or the old one? But this affair will waken or reawaken consciences, and as a demonstration it is almost American.”30

Marie’s caution was warranted. On May 5, 1928, the jury considering the Jeannerets’ League of Nations appeal decided definitively in favor of the team to be directed by Nenot, with totally new requirements for the building. Again, Le Corbusier and Pierre protested. And, again, modern architects from various countries, journalists, and professional organizations chimed in on their behalf. But the affair ended disastrously. As Le Corbusier, still smarting, described it fifteen years later, “Fair-minded people, along with the intellectual elite in every country, demanded that justice be done. Nothing of the kind occurred. The Academy and politics finally triumphed in this memorable affair, this unprecedented scandal.”31 The only solution was to move on.