XXVII

1

Two days after Le Corbusier’s return to Paris from Moscow, the president of the Cooperatives of Russia met with him to work out the agreement for the architect to do the Centrosoyuz. The Russian characterized Le Corbusier’s design as a modern palace. Although Le Corbusier was suffering from one of his terrible colds and a headache that was to last eight days, he had rarely been as completely content.

He saw the Russians as just like him: pure, brave souls scorned by reactionaries. On November 11, he wrote his mother, “The western world has shown itself to me under a rather shabby aspect. The sort of heroism, of inevitable stoicism, which exists in Russia…leaves a strong aftertaste. And I have always been sensitive to pure ideas, or to the idea itself. So I am sad to see the world rise up against an idea (however debatable). And opposing this faith and this sincerity, the rather fragile structure of bourgeois morals with all their artificiality, and injustice and falsehood.”1

His mother, he told her, was the polar opposite of those lifeless, self-deceiving people. She and his father were pure and righteous, which is why he and Albert were the same:

You are a model—a model of life, strength, confidence, and artistic generosity. You are certainly not a bourgeoise, and that is a legacy you bequeathed us at birth. To be firm in life yet to be broad-minded, so that such breadth is inspired by an element of kindness.

Georges Dubois has written me about the photograph of dear Papa (at the clinic). That teeming life cannot bear comparison with this already diminished image. Yet I find in this portrait much of what constituted dear Papa’s farsightedness—that distance he knew to take in all his judgments, that perspective which was his wisdom. Maintain your faith and your action, your precise and upright functions, as well as that freedom of appreciation which affords the heart an open road. Sunday kisses to my dear Maman.2

The compliments were a tactic. By praising both his parents for their broad-mindedness and kindness, Le Corbusier was not just pushing for Marie’s approval of his new affiliations with the Soviet Union. He had a plan to cast aside his own heritage, and he wanted her to accept it.

2

Slowly, Yvonne was being integrated into the family—to the extent that anyone might penetrate the nuclear unit of Marie Jeanneret and her two sons. Yvonne and Le Corbusier dined on occasion with Albert and Lotti and Lotti’s two daughters.

In reporting on these events to his mother, Le Corbusier commented on the difficulties of Albert being Swiss, while Lotti and her girls were Swedish. It was the lead-in to telling his mother that he thought it would be better if he and his partner shared the same nationality. He wondered what she thought of the idea of his changing citizenship from Swiss to French.

Le Corbusier knew this might not be well received. He advised his mother not to mention it to Aunt Pauline and emphasized that he wanted to be naturalized not out of disloyalty for his country but for Yvonne’s sake. Then he asked another bold question. Should Yvonne come with him to Vevey for Christmas? What did she think? We don’t know Marie’s precise answer, but he would end up going on his own.

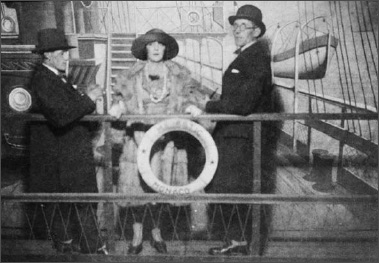

With Pierre Jeanneret and Lotti Jeanneret in the late 1920s

THAT FALL, Le Corbusier began to obsess over basic housing types. He had developed a radical theory: the assumption that Neuchâtel mountain farmhouses had been designed to withstand heavy snows was erroneous. In fact, their form came directly from Armagnac, where it rarely snowed, and had been exported to Switzerland when the Albigeois from that region were exiled to the Alps around 1350.

In Le Corbusier’s eyes, this proved that domestic architecture revealed that where we come from has greater importance than the requisites of climate or other external conditions in our current location, and that style derived from reasons other than efficacity. We may move from southern France to the mountains or from the mountains to Paris, but we remain who we have always been. Like the Neuchâtelene farmhouses in which he had spent some of the happiest moments of his youth, Le Corbusier was at heart French, even if transplanted by happenstance to Switzerland.

Architecture told the truth, he insisted—and he settled for nothing less. Those farmhouses proved that his origins were French, whatever others thought; this was as inviolable as his being, at the core, a modest and private artist as much as an architect absorbed in the hubbub. He wrote Ritter:

There is no faking when it comes to architecture, there are always reasons. In any case I am somehow comforted to know you agree with me, for I have incessantly and passionately worked in utter good faith. And this search for purity is a need for truth. For a long time you have supposed I was lost in Parisian fads. I want you to realize that having arrived at a certain pinnacle of fame, I continue living down to earth, working away, filled with ideas, devoured by time, not talking but doing. Since 1916 no more than ten people have knocked at the door of the rue Jacob where I am every morning. Later, the office is another affair: a veritable procession.

Perhaps you are unaware that since 1918 I have passionately committed myself to painting. For five years I have not exhibited, having shut my door on my daubs. Painting every morning is what allows me to be lucid every afternoon. But what battles, what dramas! And in just the last few weeks, journalists and dealers are making a great fuss about my painting. I am attempting to repress all such behavior. I do not want this matter to be ventilated just now. Which shows you how loyal I am to my brushes.3

He was, moreover, a painter in the French tradition, just as those Swiss farmhouses were quintessentially French. He was convinced the nationality he would soon make official was in his heart and blood.