XXVIII

1

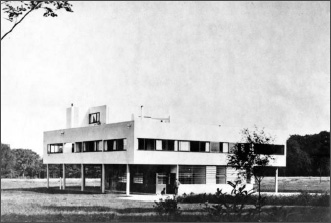

Frank Lloyd Wright called the Villa Savoye, which was completed in 1930, “a box on stilts.” Some observers likened it to a space capsule fallen onto an unwelcoming landscape. Today, it is an icon of twentieth-century design and has spawned countless imitations all over the world.

Le Corbusier considered Pierre and Emilie Savoye the ideal clients. Upper-class, prosperous, and cultured, the couple specified little more than that they wanted a summer house on their land in the town of Poissy, not far from Paris, where they lived the rest of the year. They had few demands other than adequate servants’ quarters and a garage, and they were amenable to all of Le Corbusier’s aesthetic ideas.

What he built them was, above all, a vehicle from which to savor nature. Le Corbusier’s own description of the floating white container makes clear that everything was in service of the landscape: “Site: a magnificent property consisting of an enormous pasturage and orchard forming a cupola surrounded by a girdle of high hedges. The house must have no ‘front’ situated at the summit of the cupola, it must be open to all four horizons. The habitation floor, with its hanging garden, will be raised on pilotis allowing views all the way to the horizon.”1 The purpose of the faceless building was access to the wonders of the universe.

2

The villa at Poissy resembles Le Corbusier’s previous houses but is simpler. The sashes of the industrial windows were the most refined to date. The overall form—a perfect square, supported on pilotis—is a statement of rightness and order. The ramps connecting the stories make the activities of ascent and descent feel ethereal.

This pared-down structure, confident without being arrogant, is an eloquent statement of humankind establishing its presence on earth: a modernized Parthenon. The supporting columns have none of the details of their Greek ancestors—spare and lean, smooth rather than fluted, perfectly straight rather than tapered to simulate straightness as were the Greek prototypes—but they still lend a classical order. The color is pure Mediterranean whiteness.

From the outside, the impression is of simultaneous mass and levity, a harmony of contrasts. The round, smokestack-like forms that pop through the roof play against the square block of the house. Everything is varied but congruent: the strong horizontals and verticals, the shimmering whites and bold blacks.

Services and garage space were kept at entry level and out of sight. Today, by contrast, garages declare themselves in front of homes as if they are the main point, boasting of the cars they protect and making clear that modern living is as much about commuting as residing. The Villa Savoye, while fully acknowledging its inhabitants’ dependence on the automobile with its three-car garage positioned at a convenient angle for entrance and egress, has it tucked behind the pilotis. The car serves; indeed, it charms; but it does not own its owner. Le Corbusier kept human experience at the forefront.

If you stand facing a corner of this country retreat dead-on, you experience the force of a massive minimal sculpture: an absolute, irrefutable presence. But for all its authority and precision, this building is friendly and welcoming; once you head toward the entrance, you are greeted with a wide smile.

Le Corbusier’s concept was clear: “Four identical walls pierced all the way around by a single sliding window.”2 What is achieved as you approach that body and take the splendid upward journey inside is a sequence of vistas; the act of looking is encouraged at every turn. You go from one tableau to another, from a halting view of a solid black door and white impassive walls to a sweeping vista, as in a musical progression from silence to a rhapsody.

Today, Poissy is a populous suburb, and the charm of the setting is almost completely lost. But when the villa was built, the views of fields and sky were sublime. With the latest materials assembled in a neat framework, the architect had provided an experience stunningly akin to what he had tasted on Mount Athos nearly two decades earlier.

THE HOUSE AT POISSY is designed for well-being, for dining or working under optimal circumstances, for relishing life. While more space is devoted to splendid terraces and the vast solarium than to the enclosed rooms, it has an inviting fireplace and snug womblike nooks in which to keep warm; every doorknob lends charm. The blue of the bathroom tiles is the color of the Alpine sky in clear winter weather (see color plate 7). Inside and out, there are well-proportioned tables and neat seating units. These details serve life and enhance a sense of pleasure with no unwelcome distractions. The ever-present balance of the plan helps provide calm, and the graceful lines and correct proportions of the highly refined architectural elements help one breathe deeply and regularly: all to facilitate the purposes of contemplation.

The Villa Savoye, shortly after construction, ca. 1930

The Villa Savoye is both a place to live and a temple to the sun. Most of the house, open to the sky, puts you closer to the space that surrounds the Earth. This platform for observing the universe recapitulates those Sunday outings of Georges and Marie Jeanneret and their two young boys in the snowy mountains. Everything is about the journey through whiteness, rugged and challenging in its way (neither the ramp nor the stairs are easy), offering as its reward the miraculous sky (see color plate 5).

When Charles-Edouard Jeanneret approached the Parthenon at age twenty-three, he stalled and then hurled himself ahead, prolonged the pleasure and then recoiled from it, all because the event was so overwhelming. In this athletic, balanced, vibrant, faceless building, Le Corbusier created a monument for the twentieth century of no less force and majesty than the temples of ancient Athens (see color plate 6).

3

In February 1929, Le Corbusier visited his now sixty-nine-year-old mother in Vevey. She wrote Albert that he “installed an electric light above the coal bin, a necessity in what had been such a dark hole. But his visit was not confined to such aesthetic matters…and we have spent two days of perfect intimacy together, reading Sainte-Beuve’s Portraits of Women, which Le Corbusier read aloud in a very clear voice to his delighted Maman while the latter was mending the thumbs and other fingers of her fireplace gloves.”3

At last he was devoting himself to her needs: “Edouard has now realized that not only is there the noise of the road behind the house, but on one side as well, so that I am really surrounded—he really must make sound-proof walls on all sides…. Edouard has also explained about Colombo’s bill. Thanks to him for that—I know it costs him so much time and thought.”4

With an improved relationship to his mother, Le Corbusier was ebullient. He was certain the Moscow project was going ahead, and he considered himself impervious to the economic downshifts that were soon to lead to worldwide depression. In April he wrote Marie, “The crash doesn’t affect us. Work comes in from all sides, increasingly interesting. Actually life is enthralling.” He was not blind to what was happening, just confident in his own power. “Terrible events are occurring and hard times coming! The old world must do what it can.”5

4

To his mother, Le Corbusier could reveal his frenzy and fears as well as his braggadocio. To Yvonne, he showed his heart and vulnerability. The combination stabilized him, providing rare understanding and acceptance in a world that often pounced on him.

The good relationship of these two completely different women with each other became essential to Le Corbusier. That spring, Marie Jeanneret visited Paris—as she now did periodically—to see Albert and his family and Charles-Edouard and Yvonne. Marie had come to accept her younger son’s live-in mistress, writing Albert that Yvonne was “always full of affection” and had a “really splendid countenance, the true Arlésienne type.”6 Shortly after her return to Vevey, Le Corbusier wrote her,

I have a very gay and enthusiastic memory of your stay in Paris. How I love my dear Maman! I’d have liked to spoil you, to overwhelm you with attentions, but I could only surround you with affectionate thoughts. I’m a slave to the terrible times. And if I freed myself, I should slip and fall. The kingdom of necessity! Each hour, each minute must be utilized, fecundated. The playing-field has grown so much larger. And ideas swarm, ever greater. I know that ultimately, and in spite of everything, the earth turns. But our fragile happiness, far from being found in luxury, money, worldliness, is here with me, within me, and we must be strong to help the weaker ones. Yvonne is loyal, kind, extremely attached. A constant, vigilant presence. An ever-watchful heart. What luck, simultaneous with the risks of another attempt. We must know when to stop and when to say: this is the right way. She is a little wild creature, skittish as a gazelle, and yet possessed of a very special kind of courage, a resistance, a violence I prefer to any subservience.

You were very good with her. Thank you for that…. Good night dear Maman. Your D.D.7

WHEN LE CORBUSIER wrote Yvonne during his travels, he used short sentences that resemble the text of a children’s book. She was “Mademoiselle Vvon,” “Petit VV,” “Petit Vonvon,” “Petit Von,” “Petit Vvon” while he mostly remained “DD” or “ton Dou.” He never went into any issue in depth, as he did to his mother or Ritter, and simply gave a general summary of his latest activities and let her know how he was. “All the kisses on earth” was his typical way of signing off.8

He was rarely serious, except about money and her need to take care of herself. But under the guise of playfulness and in his telegraphic language, Le Corbusier sometimes was more direct and truthful with Yvonne than when he addressed a larger audience or tried to seem literary. On a return trip to Moscow in June 1929, he wrote, “In Russia, this is how it is: the Eskimos play under the cactuses, the pilotis make the revolution, vodka is for washing, speeches slake thirst, and the Ideal continues. It is cold, but I am warm at heart. All’s well, regards and salutes from everyone here.”9

Yvonne, from a poor family, used to financial struggles, would, he believed, understand this sense of hope about the new Russia.

THE GLOBE-TROTTING ARCHITECT and the former dressmaker’s assistant were growing even closer. By that June, Le Corbusier wrote Yvonne, from La Petite Maison, declaring how happy he would be to have her see the house.

Yvonne’s relationship with the woman who likened her to van Gogh’s beautiful dark-haired “l’Arlésienne” was also strengthening. She spent months that spring making for Marie Jeanneret a smocklike blouse decorated with a flower pattern. Le Corbusier wanted to make sure that his mother adequately acknowledged his girlfriend’s efforts. Even after his mother had written Yvonne a card to thank her, he wrote back, “It was a vast undertaking accomplished with perseverance and taste. You must look charming in it. You and your flowers—it must look very pretty, at the water’s edge.”10 The peasant-style blouse was probably far too youthful in style for its wearer, but Yvonne deemed it perfect for the conservatively dressed, old-fashioned lady from the mountains.

Le Corbusier enumerated his mistress’s virtues to his mother. He pointed out that while he had been traveling to the Soviet Union and elsewhere, “Vonvon has had bad times alone in the house, but she has a stubborn little philosophy, and she resists. Moreover she is used to my being far away at my work. The house is charming, clean as a whistle; each time I return I’m like a fox in his lair.”11

In a letter that crossed his in the mail, his mother had written of “how much pleasure this pretty blouse has given me and how useful it will be.”12 Coming from Marie Jeanneret, it was a major step forward.

5

Yvonne’s letters to her boyfriend’s mother were written in perfect schoolgirl’s penmanship, the capital letters embellished with curlicues, in lines that were ruler straight. Addressing the older woman as “Chère petite maman,” thus making herself a member of the family, Yvonne regularly told Marie Jeanneret that every single day she was thinking of her. She referred periodically to the blouse, in one letter saying how happy she was that it fit well: “As for the bill, I am a grande couturière who enjoys offering the new fashion to dear Mamans as nice as you are.”13

Yvonne provided a picture of everyday life on the rue Jacob. In mid-June 1929, she wrote that she was making two gingham dresses to have them ready for her and Edouard’s departure for Le Piquey on July 15. She recognized, though—after he had made a second trip to Moscow—that the work that had piled up by the time he returned at the end of June would probably push back their travel date.

Yvonne was doing everything she could to ensure her role as a dutiful member of the family. Lotti was away, and in order to spend more time with Albert, Yvonne intended to get her driver’s license, which would make it easier to get out to his house, so far away in the sixteenth arrondissement. She began writing Marie Jeanneret with increased frequency—telling her what color skirts to wear with the blouse, when to wear it puffed out, and when it should be tucked in tight—and assured her that she would like to see her. But Le Corbusier’s mother did not write back. On August 10, the architect wrote her anxiously, “What does your silence mean?” After reminding her of his and Yvonne’s overtures, he continued, “Your big baby Albert is no longer there to fill your days. How about a word to console the younger son?”14

Yvonne was, Le Corbusier assured his mother, “loved by everyone here.” Now he and she, together, proposed that Marie make a plan to come to Paris to celebrate New Year’s, although it was still half a year away. After all, much as he adored his mistress, his mother’s position was unassailable: “I think of you every day. I expect your letter every noon. A word, a card, if you please.”15 Occasionally she replied—mainly to report on the leaking roof.

LE CORBUSIER regularly listed his achievements for his mother. Once he and Yvonne got to Le Piquey at the end of August, he told her that besides being asked to design a forty-two-story skyscraper in the United States, he swam every day and had the perfect girlfriend who allowed him to be himself. “Yvonne is the darling little elf who knows how to let me be free in my initiatives,” he informed his mother.16 Three weeks later, he added, in a similar vein, “Vonvon is extremely accommodating and nice: she makes all our undertakings easy.”17 This was his constant message to his remaining parent: that Yvonne was an essential ingredient in his ability to succeed.

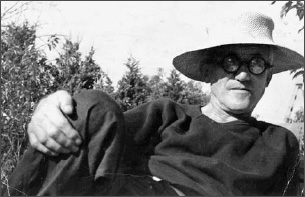

On vacation at Le Piquey, late 1920s

ON SEPTEMBER 3, Yvonne herself wrote another long letter to Marie, explaining that while Le Corbusier was in South America, where he was about to embark on a major effort to promulgate his urbanism, she would be at home sewing and embroidering, following designs he had drawn for her to work on in his absence: “Dear Maman, I’ve begun my bedspread, green linen with big stars sewn with different yarns, just dazzling! It’s taking a long time but it’s not tiresome work. I’ll have plenty to do during his absence, and the time will seem shorter.”18 She was also canning cornichons and onions and trying new ideas for her makeup and hair.

It was just what Le Corbusier wanted.