XXXII

1

On the other hand, in America, in the Republic, one must waste a whole day in paying serious court to the shopkeepers in the streets, and must become as stupid as they are; and over there, no opera.

—STENDHAL, The Charterhouse of Parma

The Museum of Modern Art in New York organized an exhibition of Le Corbusier’s recent work that was to start on October 24, 1935. At last the architect went to the United States. Following the exhibition opening, he was to go on a lecture tour. He had agreed to lower lecture fees than he wanted—between seventy-five and one hundred dollars per engagement—because he was so curious to see North America and hoped to encounter clients there. He conceived of the United States as a gold mine, which made him irritated about the fees but optimistic that this was the land of unparalleled opportunity.

Le Corbusier left Le Havre on October 16, ten days after his forty-eighth birthday. Sailing first-class on board the Normandie, the legendary French liner, he wrote down English phrases he expected to need in the upcoming weeks: “inside street not exposed to rain, snow, or sun,” “swimming pool,” “people who bore me,” and “here’s looking at you,” written next to a drawing of a martini glass in the form of an exclamation point.1

As soon as he arrived, he got off to a rocky start with the American press. A New York Herald Tribune article bore the headline “Skyscrapers Not Big Enough, Says Le Corbusier at First Sight,” and smaller headers declared “Finds American Skyscrapers ‘Much Too Small’…Thinks They Should be Huge and a Lot Farther Apart.”2 The New York Times also put a negative spin on Le Corbusier’s initial impressions with the headline “Venice ‘Best City,’ Le Corbusier Finds” and the statement “he feels the average city leaves much to be desired.”3

“Skyscrapers Not Big Enough, Says Le Corbusier at First Sight,” New York Herald Tribune, October 22, 1935

Believing that the skyscraper was a miracle of modern urbanism and the machine age, the architect was disappointed with the examples he found in New York. He thought a building of great height should be large enough to contain up to forty thousand people, and that if it was that size it could stand alone and face nothing but the cosmos: “The true splendor of the Cartesian skyscraper: the bracing, stimulant, optimistic, radiant spectacle offered from each office through the limpid windows opening onto space. Space! This response to the aspirations of being, this release offered to the respiration of the lungs and the beating of the heart, this effusion of vision from afar, from on high, so vast, infinite, limitless. The total sun in a pure, fresh air afforded by mechanical installations.”4 He felt that New York’s skyscrapers did not put their inhabitants in direct connection with the wonders of the universe, were too small, and were too numerous and too close together, forcing people to look directly at the windows of another building rather than over the landscape or toward the sun.

He considered the city’s tall buildings the manifestation of the selfishness inherent in capitalism. The craving for personal financial gain mattered more to their developers than did the benefits to humankind. The many small-scale skyscrapers of New York were the direct result of human competitiveness gone unchecked.

The press was not going to give him an easy time about this or much else. Le Corbusier’s solution to the needs of the city—the Ville Radieuse—was translated in the Herald Tribune as “Town of Happy Light.” It is thought that the anonymous journalist responsible for that misnomer was Joseph Alsop, who spoke French perfectly but had little use for modernism and happily belittled it. Alsop mocked “M. Le Corbusier” as someone “whose egg-shaped head and face, bisected by a pair of thick spectacles with a heavy black frame, make him look like an up-to-date prophet.”5 It was not the welcome Le Corbusier had anticipated in the land where he hoped to realize his boldest aims.

Even though Le Corbusier quibbled over the size of America’s skyscrapers, they were a revelation to him. He was inspired by these buildings to abandon his usual stance against architectural historicism and the use of decorative elements on building exteriors. Having always declared his distaste for the architecture of the High Renaissance and his belief that new buildings should be completely modern in appearance, he now reversed himself on both fronts: “So it was in New York that I learned to appreciate the Italian Renaissance. You might think it was real, it was so well done…. The Wall Street skyscrapers—the oldest ones—add on to their summits the superimposed orders of Bramante, with a clarity in the moldings and the proportions which delight me.”6

Before he took the trip to the United States, Le Corbusier had imagined its skyscrapers constructed of steel, which he pictured as the dominant material of New York and Chicago. He was shocked to discover that many were clad in stone instead. Rather than having this unexpected use of a possibly inappropriate material mitigate his pleasure, here, too, he found himself happily surprised: “I must admit that this stone is lovely under the seaboard skies of New York. The sunsets are moving. The sunrises (I’ve seen them) are admirable: in the purplish mist or the dim atmosphere, the solar fanfare explodes in a salvo, raw and distinct on the side of one tower, then on the next, then on so many more. An alpine spectacle which illumines the city’s vast horizons. Pink crystals, of pink stone.”7

Focusing on what Le Corbusier disliked rather than what he admired, the journalists missed the way the world-famous architect still had the soul of that twenty-year-old who had succumbed to the colors of Siena.

2

Three days after the Normandie docked in New York, Le Corbusier gave a radio address from the RCA Building. He was introduced to his audience as “the artist-architect whose influence is recognized in all parts of the civilized world” by a Mrs. Claudine Macdonald, who explained that he would speak in French and she would translate.8

Le Corbusier described to the audience the vision he had just before his arrival, when the Normandie had stopped for quarantine, required at that time: “I’ve seen rising out of the mists a fantastic, almost mystical City. ‘Here is the temple of the New World!’ But the ship moves on, and the apparition has turned into an image of an unheard-of savagery and brutality.”9 Standing there in his impeccable suit, the architect continued,

This is certainly the most apparent manifestation of the power of modern times. Such brutality and savagery by no means displease me. This is how all great undertakings begin: by strength.

At evening, in the city’s avenues, I have come to an appreciation of this population which, by a law of life all its own, has managed to create a race: fine-looking men, very beautiful women.10

Le Corbusier declared, “I have brought into my realm of architecture and urbanism, with the simplicity of a professional who has devoted his life to the study of the first cycle of the machine age, certain propositions which appeal to every modern technique but whose final goal is to transcend mere utility. This indispensable goal is to give men of the machine civilization the joys of heart and health.”11 Here, the celebrant—the robust athlete and lover of women—and the manic architect who worked to make concrete and superhighways the frank vocabulary of modern life were one and the same: possessed by a supreme reverence for the magic of existence.

LE CORBUSIER walked through the rest of the RCA Building with Fernand Léger, who was also having an exhibition of his work at the Museum of Modern Art. At the top of the seventy-story-high stepped tower, he was riveted by a large red needle; it was a second hand turning in a large clock that showed the passage of each minute in a circular frame marked one to sixty. To the side of this clock there was an hour clock. He said to Léger, “The hours will return tomorrow. But this first dial, of seconds, is something cosmic, it is time itself, which never returns. This red needle is a material witness of the movement of worlds.”12

“Time belongs to architecture,” he told his radio audience. “Today the city of modern times can be born, the happy city, the radiant city.”13

The United States, where stodginess was not as embedded as in Europe, was where such a birth could happen. “America, in permanent evolution, and in possession of infinite material resources, and animated by an energy-potential unique in the world, is indeed the first country capable of achieving this task today, and in a condition of exceptional perfection. It is my deepest conviction that the ideas I am setting forth here and which I am offering in the phrase ‘Radiant City’ will find their natural terrain in this country.”14

In the upcoming weeks Le Corbusier explained his concepts to anyone who would listen and searched for the clients who might transform them into reality. He gave lectures in Connecticut at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford and at Wesleyan and Yale Universities; in Poughkeepsie, New York, at Vassar Collage; and in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at Harvard University and MIT. Then he headed south to the Philadelphia Art Alliance; north again to Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine; and then south once more to Princeton University, where he gave a sequence of three lectures before proceeding to the Municipal Art Society of Baltimore and returning to New York to speak at Columbia University—all this before heading off for a week in the Midwest. He was like a tireless politician on the campaign trail, energized by his faith in himself and his mission.

3

He had imagined audiences would embrace him as a messiah. The students and museumgoers who attended his talks were less than he hoped for, but there was one person who accorded Le Corbusier total understanding.

Marguerite Tjader Harris, a bright and lively American writer, was the daughter of a Swedish inventor and sportsman and an American heiress. She had a mesmeric smile, her father’s well-defined Scandinavian features, and her mother’s wealth. Married in 1925 to Overton Harris, a prominent New York attorney, in the early 1930s she had left her husband in hopes of finding a happier life in the Alps with their three-year-old son, Hilary.

In Vevey, when she wasn’t skiing or mountain climbing, the blue-eyed, red-haired Tjader Harris looked ravishing in her stylish clothes. She favored turban hats and sported a coat with an oversized leopard-skin collar and cuffs that matched her toddler son’s overcoat. She was quietly at ease in the world; in the sailing season, she did not hesitate to reveal her capable and athletic body.

One day early in 1932, Tjader Harris was out walking near Lac Leman. She gave in to her curiosity about what lay on the other side of the wall surrounding the garden at La Petite Maison and rang the bell. The diminutive, white-haired Marie Jeanneret appeared. Tjader Harris was instantly captivated by the older woman’s African slippers. Embarrassed to have disturbed her, the heiress faltered and then asked if the house was for rent. Le Corbusier’s mother explained that it was not, that her son had built it for her to live in year-round. When Tjader Harris then expressed her admiration for the design and for the slippers, Marie Jeanneret invited her in.

About a month later, Tjader Harris met the son who had designed the house. They began to see each other whenever he visited his mother. Soon enough, they were driving through the vineyards above the lake, discussing where she, too, might build a house designed by him. Le Corbusier assured her that the terrain was perfect and that it would be an interesting project. She quickly warned him that they could not start until she knew more about her current financial situation, which was changing because of the Depression and because she was in the process of a divorce. It would also depend on how her mother, who lived in Connecticut, felt about the project. Nonetheless, by the end of April, Le Corbusier had made plans; he told Tjader Harris that this was his way of expressing his gratitude for her kindness to his mother.

Marguerite Tjader Harris sailing, Long Island Sound, 1920s

At the same time, Tjader Harris had written to warn him that she was skeptical about her ability to proceed. The heiress had learned that her family was in dire financial straits—at least by the terms of the rich—and that she would have access to only a fraction of the funds she would need to build. In error, she addressed the letter to the rue de Seine rather than the rue de Sèvres. The letter was therefore delayed, and Le Corbusier had already sent her his ideas before receiving the warning.

Tjader Harris then decided that she could consider building a much smaller house if Le Corbusier could come up with a budget of between twenty-five thousand and thirty thousand Swiss francs. She also wrote the architect that she had seen his mother again and greatly admired the older woman’s “splendid gayety of mind.”15

At the start of May, Tjader Harris received several neatly executed bird’s-eye views of the revised house. Ecstatic, she took an apartment near the beach in Vevey in hopes that she would be able to start the building project nearby. She wrote Le Corbusier that his design was “the realization of my dreams which you have crystallized so perfectly.”16 Ostensibly she was just discussing architecture and a house, but her tone had all the portent of a romance in the making.

The project had summoned a burst of energy. Le Corbusier’s design had two wings built on pilotis that interlocked in a bold central space with a third, shorter wing shooting out from the middle and supported by taller columns that elevated it above the other two. There was also a semicircular extension that resembled a Romanesque apse. The agglomeration of terraces, ramps, and gracious living spaces was a plastic manifestation of unmitigated ecstasy.

NOTHING FURTHER HAPPENED with the house project, but Marguerite Tjader Harris and Le Corbusier remained sporadically in touch. In 1934, shortly after her marriage was officially terminated, the divorcée sent Le Corbusier some photographs she had taken of La Petite Maison, for which he thanked her warmly.

As soon as he was in New York at the Park Central Hotel, he wrote her again. By now he was addressing her simply as “Amie.” Tjader Harris was at her mother’s house in Darien, Connecticut, an hour’s train ride north of New York’s Grand Central Terminal. He gave his complicated schedule—with the key information that he would be free from 11:30 p.m. on the coming Thursday until noon on Friday. A series of letters followed in rapid succession, simply to tell her even more precisely when he would be available. Because of professional obligations, the best moment would be starting at midnight.

They saw each other sooner, however. On the weekend before the Thursday to which he referred, Marguerite Tjader Harris drove into the city. In 1984, Tjader Harris wrote a “Portrait of Le Corbusier” that has never been published. In it, she describes Le Corbusier’s first Saturday in New York, five days after his arrival. She and he went to the top of the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and the RCA Building so that he could observe the city from above. This is another case of a discrepancy in different accounts of Le Corbusier’s life. In When the Cathedrals Were White, the book Le Corbusier wrote in 1937 about his American trip, the architect describes going to the top of the RCA Building on his third day in the United States—only hours before his opening at the Museum of Modern Art a few blocks away—and makes it the occasion of his observing the clock needle with Léger. Tjader Harris’s recollections have him first reaching that sweeping view of New York two days later. It seems likely that Tjader Harris’s account is the more reliable, and that when Le Corbusier wrote his memoir of the trip three years later, he made Léger his companion because he had reasons to leave her out of the scenario.

Le Corbusier and Tjader Harris took the subway down to Wall Street and up to Harlem: “He was like a horse, fretting against the bridles of his many activities…. Already, he was trying to formulate some form of urbanism that could bring order into the confusion he saw…. You could feel how his brain registered every impression, visual and audible; one minute he was enthusiastic, the next, disgusted.”17

That evening, Le Corbusier and Marguerite Tjader Harris went to Connecticut. The small and exclusive residential enclave on Long Island Sound was almost entirely the bastion of rich white Protestants, a “restricted community” where neither Jews nor blacks owned property and where Tjader Harris was among the few Catholics. She lived with her six-year-old son and her mother in the family’s Victorian mansion.

They also owned a beach shack nearby, on a small island. A simple and straightforward cabanon with a fireplace and a deck that faced the sea, it could be reached easily by rowboat. Le Corbusier and Tjader Harris went out there that evening. He impressed her greatly when he removed his glasses and dove into the bracing saltwater.

For years to come, the architect and the American divorcée reminisced about their subsequent hours in the shack, their romance at the edge of the sea. When Le Corbusier ultimately built his getaway in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, it strongly echoed the place where he and Tjader Harris spent that October evening.

4

New York remained Le Corbusier’s base camp during the upcoming weeks as he gave his lectures to the north and south of the city. This served well for trysts with Marguerite Tjader Harris. Besides meeting in the middle of the night, the two went to jazz clubs in Harlem and toured the region.

The automobile figured in their romance. Le Corbusier’s urban schemes featured highways as central elements; vehicular circulation and parking facilities were pivotal concerns. Beyond recognizing the growing reality of cars, the architect had also long reveled in their capability and the power and fun they afforded their users. He loved to drive from Paris into the French countryside with Yvonne or on his longer trips to Spain or Switzerland. Now he was in the country of Henry Ford and the assembly line and of highways that allowed higher speeds. With Tjader Harris in that autumn of 1935, he experienced the pleasures of driving as never before.

Marguerite Tjader Harris owned a brand-new Ford, a powerful V8 painted a sporty tan.18 Six-year-old Hilary was happy in the rumble seat, and the three of them took to the road. The weather was ideal, the days crisp and bright. Le Corbusier marveled at the noble bridges spanning the rivers surrounding Manhattan. The George Washington Bridge struck him as the most beautiful in the world. Taking its giant step across the daunting width of the Hudson, it was marvelous with its steel cables and its height that permitted large ships to pass underneath. Le Corbusier felt that suspension bridges were “a spiritual feature,” and that the G.W. was “the sole site of grace in the disheveled city.”19

When they left Manhattan through the dramatic darkness of the Holland Tunnel and crossed the marshlands of New Jersey, Le Corbusier was likewise exhilarated. Without indicating who his traveling companions were, he later described the experience in When the Cathedrals Were White. He wrote, “This afternoon I crossed the Hudson through the Holland Tunnel, then took the ‘Sky-Way’, so-called for the way its enormous length rises high above the industrial districts, the coastal bays, the railroad lines and highways, on its arches or its pilotis. A roadway without art, for no thought of that was taken, but a prodigious tool. The Sky-Way rises above the plain and leads to the sky-scrapers. Coming from the flat reaches of New Jersey, it suddenly reveals the City of the Marvelous Towers.”20

That elevated roadway was the realization of many of the architect’s most cherished dreams. It provided direct contact with the sacred space of the sky, and it stood on pilotis that enabled it to float ethereally over the earth. It did so as the result of intelligent forethought that harnessed the potential of modern materials. To experience these wonders in the company of a beautiful, worldly, dynamic woman who was his lover gave him new faith in his own ideas for urban circulation.

ON THE EVENING of Thursday, October 31, the divorcée compliantly came in from Darien and went up to Le Corbusier’s room at the Park Central Hotel, as specified, shortly before midnight. The architect had just returned from dinner with twenty-seven-year-old Nelson Rockefeller, a member of the Junior Advisory Committee at the Museum of Modern Art, and the architect Wallace Harrison, who was related to Rockefeller by marriage. Le Corbusier saw Rockefeller and Harrison as perfect stepping-stones to his own success, although in time he realized that the woman who appeared in his hotel afterward was his only real loyalist.

For the rest of Le Corbusier’s visit to America, Marguerite Tjader Harris met up with her lover as often as his schedule permitted—sometimes at the hotel, at whatever hour he designated, and sometimes in Darien. There they would sit in the evening by the fire with Tjader Harris’s mother, whom he likened to his own, and her dog, whom he compared to Pinceau, his and Yvonne’s schnauzer. Hilary, whom everyone called Toutou, was also on the scene. During the days, Tjader Harris and Le Corbusier often repaired to the shack on the small island in the sound.

Unlike the other women in his orbit, Tjader Harris had a rare combination of intellect, passion, and steely self-control. The independence he generally eschewed in women were part of what made the athletic, elegant Nordic redhead desirable. These halcyon escapades of 1935 were only a beginning.

5

The lectures Le Corbusier gave in America focused on La Ville Radieuse and his recent domestic architecture. Robert Jacobs, his translator on the tour, who stood at the architect’s side, was nicknamed “the faithful shade.”21 The lectures were often accompanied by a silent film that showed the Villa Savoye and the villa at Garches, accompanied by a recording of music composed and played by George Gershwin.

Le Corbusier’s favorite lecture venues were at the East Coast colleges and universities attended mostly by upper-class youth. These enclaves of stone buildings and gracious lawns, reserved primarily for the elite, fascinated him. In the midst of the Depression, one generally had to come from a moneyed family to be at one of the Seven Sisters or at an Ivy League university for men. To Le Corbusier, who had had no experience of anything remotely like them, Columbia, Yale, Harvard, and Princeton were each “a world in itself, a temporary paradise, a happy stage of life.”22

Vassar College, with its impeccably manicured grounds and old-fashioned brownstone buildings, reminded Le Corbusier of a luxurious club. At this “joyous convent”—the architect’s term once he learned that its entirely female student body was there for four years—he was captivated by the young women onstage when he attended a student play shortly after arriving on the campus. He leered at them whether they were “in overalls or bathing-suits. I delight in observing these splendid bodies, braced and purified by physical training.”23

Later that same day, six hundred of these fine female specimens filled an auditorium to hear Le Corbusier lecture. Looking at the sea of privileged, well-brought-up women, his first thought was “good blood.” He was surprised to discover that they all understood French, which further confirmed their distinction.

The Vassar students were his most attentive audience to date. In the course of speaking that afternoon, he came to believe that they would be his “best propagandists.” When he was done telling them about new cities and unprecedented ways to live, they stampeded toward the stage. His new devotees feverishly cut up his large drawings so that each of them could take home a small fragment, like a holy relic. “One piece for each amazon,” he recalled.24 They begged him to sign the pieces of paper, which he willingly did.

This felt like a real start at convincing the most influential people in the most influential country of the world to take up the concept of the Ville Radieuse. Surely those young women would promulgate his agenda for an architecture and urbanism that integrated the pleasures imperative to human existence with modern materials and a new vision. According to his own proud calculations, he made, in the course of this seminal trip, two tenths of a mile of drawings: six rolls of paper, each fifty meters long. As he gleefully watched the undergraduates tearing apart some of the sacred scrolls, his confidence soared: “The Vassar drawings were the consequence of an especially good mood. The amazons reduced them to shreds!”25

Once the onslaught was over, the students asked him intelligent questions in impeccable French. They revealed impressive knowledge of sociology, economics, and psychology and a keen concern with the serious problems then confronting the world. Faced with their earnestness, he assumed a humility that had a phony ring to it: “I never felt so stupid. ‘But, Mesdemoiselles, I know nothing about the problems you envisage; I am merely an urbanist and an architect and perhaps an artist. Mesdemoiselles, you overwhelm me, you are too serious, I shall leave you and join those who are munching cookies!’”26 Today, students would boo or storm out; in the mid-1930s, they were charmed.

Following the question-and-answer session, Le Corbusier went to the house of an art-history professor and began to drink whiskey. When “a superior student” told him she was studying Caravaggio, the architect responded that he disapproved and asked her to explain “the source of the strange power in this equivocal man.” He imperiously asked the student, “Do you too suffer from repression?”27

It was beyond him that a young woman would devote her time to the blatantly homosexual Italian painter. Le Corbusier attributed the student’s misguided taste to an essential problem of America’s unwise preoccupation with the facets of the human psyche best kept private. Given his closeness to William Ritter, it isn’t that he condemned homosexuality. Rather, the architect joined a handful of other influential modernists—Josef Albers, the Bauhaus professor who had two years earlier begun teaching many of the leading young artists of the next generation at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, was another—who were rankled by the American taste for autobiographical art that deliberately revealed the psychological issues of its maker. These purists disdained all fondness for Duchamp and the Surrealists. They preached an adherence to the tenets of pure geometry and clearheaded design and an avoidance of issues they believed were extraneous. Le Corbusier reflected, “Caravaggio, rising out of the past, slakes a certain thirst of the American soul; furthermore the ‘surrealism’ of today has conquered the USA, the USA of the timid and the anxious.”28

Still, he had great hopes for the twelve hundred women of Vassar College. The architect came to a conclusion that was remarkable in light of the woman he had chosen to marry: “In American society, woman exists by means of her intellectual labor.”29 These women of the new world could achieve great things.

The day after his lecture, Le Corbusier’s admiration for the egalitarian spirit of these female undergraduates increased when he boarded the train to return to New York. It was a Saturday morning, and a group of students was heading into the city as well. They flocked toward the smoking car. Not only were the young ladies undaunted that their fellow smokers were muscular male dockhands and factory workers, but they relished the men’s company. Le Corbusier wrote about that sight: “Democratic spirit. At Vassar I detected hints of communism in this wealthy circle. It’s a familiar experience: the ‘good society’ of the intelligenzia, rich and eager to spend money, looks forward to the ‘great revolution’ with a touching ingenuousness.”30 His tone was snide, but he loved the warm spirits and good heart.

6

The lecture tour also gave Le Corbusier his first exposure to American football culture. Princeton had a winning team that year, and the visiting architect was impressed that sports rivalry could serve as “an intense springboard of solidarity and enthusiasm.”31

The architect considered Princeton and the other institutions with fine grounds and Gothic buildings as erstwhile attempts at Eden in their removal from ordinary reality. But he questioned the merits of the isolation imposed by these enclaves. He recognized the idyllic aspect of four years in an artificial paradise but wondered if it would be better at this seminal moment of development to have “the total expanse of life, with its flaws, its poverty, its anguish, its greatness?”32 When he was the age of these undergraduates, after all, he had been sojourning independently from one European city to the next, taking part-time jobs and seeking apprenticeships.

After Ema and Mount Athos, the rural villages of the Baltic, and the workers’ clubs in Moscow, Princeton presented a form of group living Le Corbusier had never before encountered: “These rugged boys—all of them athletes—this security of material life, this simple joy of camaraderie…these are the master trumps in America…. Across the USA, the student tribes form their de luxe encampments.”33

Le Corbusier preferred the independence required of students at the Sorbonne, who lived on their own: “I’m drawn by the pathos of life and its dangers; much less by the assurance of these spoiled daddy’s boys, so well-fed, well-scrubbed, well-groomed.”34 Those sons and daughters of privilege were deprived of important things. The nature of their physical surroundings, too elegant and too isolated, was complicit in the problem.

LE CORBUSIER greatly admired the energy of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and of the building campaign recently undertaken by the Works Progress Administration. An intermediary tried to arrange a meeting between the two men. As with Roosevelt’s predecessor Herbert Hoover, Le Corbusier was to be disappointed. When word came back that Roosevelt did not have time, Le Corbusier blamed the all-consuming 1936 election campaign for the president’s missing something far more important than politics: “From my brief experience of the men in government, I should say they are not well-informed. They haven’t time to inform themselves and to meditate.”35

But most people were excited to meet the architect, and his lecture became part of the legacy of each institution where he appeared. At Bowdoin College, it is still remembered that at dinner at the president’s house, when a guest asked the famous visitor for his views about city planning, he pushed away the dishes, got one of the female guests to give him her lipstick, and sketched in brilliant red all over the tablecloth.

The lecture audiences were invariably attentive and excited, with no protests like those in Paris. On the other hand, the dean of the Harvard architecture school, where Le Corbusier spoke, labeled the visitor “a much over-rated individual.” The Christian Science Monitor disparaged the architect by reporting that he “never attended school, not even primary school.”36 At a formal dinner in Philadelphia, guests were appalled when he tried out certain new English expressions like “son of a bitch.”

Among the people Le Corbusier offended at that dinner was the cantankerous art collector Dr. Albert Barnes. As a result, Barnes denied him the privilege of going the next day to view his extraordinary collection of Cézannes, Seurats, and Renoirs. Le Corbusier did not accept the collector’s refusal to open his doors. Since L’Esprit Nouveau had, in 1923, published an article by Maurice Raynal about Barnes and his collection and educational theories, the architect felt he had earned the right of entry. He dispatched a note to that effect.

Barnes replied that Le Corbusier would be allowed to visit after all. The collector, however, specified a day well after the architect’s scheduled departure from Philadelphia, and he also stipulated that nobody from the Philadelphia Art Alliance, the organization where Le Corbusier had lectured, could accompany him. Le Corbusier replied that while he was “infinitely respectful of pride and wealth,” he could not wait “four days on the Barnes Foundation doorstep.” He signed the letter, “The founder of L’Esprit Nouveau who from 1919 to 1925 fought the good fight for the artists you buy.”37

The maneuver failed. After he returned to New York, Le Corbusier received a typewritten reply, unsigned and in French, a language he knew Barnes did not speak. It was addressed to “Maître Corbeau, dit Le Corbusier.” Barnes wrote, “I’ve heard that you were quite drunk last Friday at the Sausage Alliance in Philadelphia; I presume you were in a state of similar intoxication when you scribbled your remarks. In any case, Maître Corbeau now knows that Maître Renard has no respect for clowns nor for the Nitwit Alliance that employs them.” The missive was signed “Maître Renard, known as ‘Albert C. Barnes’ founder since before 1910 of the New Spirit which seeks to differentiate the true from the false in art and culture.”38

Le Corbusier responded calmly. He suggested that two people who loved the same things and shared certain passions should not feud and said that the three whiskeys he had consumed at the Art Alliance dinner had not made him drunk. Taking the upper hand, he wrote Barnes, “I enjoy a good fight in life, and I engage in such combats without fear. But in this instance I believe hostility is useless.” It was time for “the duel to come to an end.”39 The letter came back unopened. In large circular handwriting, Barnes had written “Merde” on the sealed envelope.

Le Corbusier recounted the feud and quoted extensively from the exchange of letters in When the Cathedrals Were White, with the conclusion that “it testifies to the crude satisfactions of the men who in one, two, or three generations have ‘made America.’ If you like, it is a sort of ‘cowboy’ story!”40 The word “cowboy” was in English in the otherwise French text.

He was eventually to be more flummoxed by those cowboys than he ever could have imagined.

7

In the third week of November, Le Corbusier began to make his way westward toward Chicago. Near Detroit, he visited the Ford River Rouge plant, one of the largest assembly-line buildings in the world. Watching the production of six thousand cars per day, he felt he had entered the modern world at last.

That efficient, state-of-the-art automobile factory exemplified the ideal political state: “With Ford, everything is collaboration, unity of outlook, unity of goals, perfect convergence of thought and action.” By contrast, the practice of architecture in modern Europe struck him as inefficient and problem ridden: “With us, in the factory, everything is contradiction, hostility, dispersion, divergence of views, assertion of opposing goals, marking time.”41

Ford’s production techniques convinced Le Corbusier that the traditional practice of architecture had not yet caught up to the possibilities of the modern world. He decided, as if he had never known it before, that architecture must make human well-being its primary goal as assiduously as Ford devoted itself to producing automobiles. Studios and factories alike must utilize modern techniques to achieve that objective with maximum efficiency. The assembly line demonstrated the possibilities of realizing the dream of allowing individual liberty and collective effort to thrive in perfect tandem with each other.

Not since the monastery at Ema had Le Corbusier been as excited by an architectural prototype as he was in that facility near Detroit. The vast factory with its cacophony of sounds and its production of the vehicles essential to everyday life in a vast and powerful country had a similar effect to the fifteenth-century retreat devoted to the contemplative life on the outskirts of Florence. It was neither the first nor the last time in his life that Le Corbusier had fallen for a false god. His vision of the core of American capitalism helped pave the way for what soon was more than a flirtation with the forces of fascism and repression.

8

In Chicago, Le Corbusier came to admire the buildings of Louis Sullivan but disparaged both the poverty of the slums and the spread of America’s second-largest city horizontally into suburbs. Insufficiently connected with an urban core, isolating families on little plots of land, these communities were the antitheses of Le Corbusier’s ideas. He told his Chicago audiences that American production techniques had led the way in what he termed “the first machine age civilization”—the century from 1830 to 1930—but that now capitalism was destroying American cities by producing architecture not in the best interest of urban planning.42 He still believed that the United States had the potential to lead the world in facilitating a new urbanism—if only the country would listen to him rather than continue to cluster its skyscrapers and expand its suburbs. Le Corbusier showed his own work—the Swiss Pavilion as well as unbuilt projects like his art museum and the Palace of the Soviets—as examples of what public buildings should look like. He also pushed his urban schemes.

Le Corbusier’s hosts tried to organize a meeting between him and Frank Lloyd Wright, who lived a couple of hours away. It made perfect sense for two of the greatest names in modern architecture at least to shake hands. Along with Mies van der Rohe—who was soon to move to Chicago but who had for the time being remained in Berlin following the closing of the Bauhaus under pressure from the Nazis—and Alvar Aalto, in Finland, Le Corbusier and Wright were the gods of the field. But Wright declined to make the journey to meet the visitor from Paris, let alone to hear him lecture. To the Chicago-based architect who had invited him, Wright wrote, from Taliesin, in Spring Green, Wisconsin, “I hope Le Corbusier may find America all he hoped to find it.”43

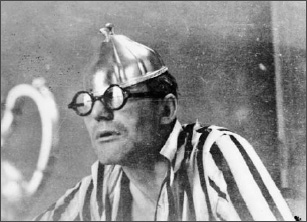

At the Drake Hotel, Chicago, Thanksgiving morning, November 28, 1935. Photo by Robert Allan Jacobs

A more successful encounter was arranged on Le Corbusier’s behalf with a prostitute, procured for him by his translator. When he woke up next to her on Thanksgiving morning in the Drake Hotel, the architect was in such good spirits that he took a silver-plated dome from room service and donned it as a crown, posing for a photograph in which, with his striped pajamas and trademark glasses, he resembles a circus clown. Later that same day, his spirits high, he took a TWA flight back to New York. Le Corbusier was invited into the cockpit, which he considered an architectural marvel, especially as it facilitated a smooth and quiet journey that took only three and a half hours.

9

The architect stayed in New York until mid-December. This time he was at the Gotham Hotel, an ornate building at Fifth Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street. (Today it is called the Peninsula.) Feeling that he was at the center of a universe—one that had even more potential than the inner sanctum of Argentinian high society, where he had anticipated his ascent as master builder six years earlier—he was determined to use his proximity to wealth and power to full advantage.

In those few weeks, he took every chance he could to pitch ideas to Nelson Rockefeller. Rockefeller’s mother was one of the three founders of the Museum of Modern Art, and the young millionaire was closely connected to many people in the financial and political establishment. Le Corbusier imagined Rockefeller as the magician who might enable him to realize a new League of Nations proposal, a housing scheme in the New York area, a contemporary-art museum anywhere, a headquarters for CIAM in Paris, and his design for a pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair.

Once he was back in France, all these prospects came to nothing. But for those few weeks in New York, Le Corbusier believed he was on the verge of major conquests.

ON DECEMBER 6, the former child of La Chaux-de-Fonds went to a ball for 2,500 guests at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel. The ball, given by the Beaux-Arts architects, had the theme of a night in India. When Le Corbusier had gone a few days earlier to rent a costume, he had been offered a turban and “brocaded robe” suitable for a raja or a khan. But he had other ideas: “Thanks, but no usurped titles! Not being a handsome fellow, I’ll leave my anatomy in peace. Despite his protests, I’ve obliged the man who rents costumes to give me a prisoner’s outfit, blue and white stripes, and a vermillion tunic of the Indian army (my supplier would have preferred a top officer’s outfit!); I dislodged an enormous gold epaulette which I pinned on the left side. No kepi, sir, a pointed white dunce cap, please. To create a balance of colors, I attached a big blue scarf across my chest to a gold sword-belt. Damn! no pockets in my prison trousers: banknotes in my socks then, my pipe and my tobacco-pouch stuck in my belt. And to finish off, on my cheeks and forehead, three broad yellow patches of different shapes to mislead the curious.”44

Most of the people at the Waldorf that night bowed to fashion or looked over their shoulders to figure out what everyone else was doing. Le Corbusier, as always, invented his own way. At the same time, he had outfitted himself to dance at the Waldorf with memories of Josephine Baker in his arms.

10

When Le Corbusier had set sail for America, he had expected his wildest dreams to come true. By the time he headed back to France two months later, he was devastated.

Le Corbusier characterized America’s culture by focusing on the taste for Caravaggio which had initially irritated him on his Vassar visit.

Caravaggio, a sixteenth-century Italian painter, “worked in a studio painted black; the only light came in through a trap-door in the ceiling.” Stop there! Here we discover an aspect of the American soul. If we add today’s surrealism, widespread in American collections, to Caravaggio, our diagnosis will be confirmed. This chapter will draw us into the dark labyrinth of consciousness haunted by young people with anxious hearts.

Caravaggio in university courses, surrealism in collections and museums, saltpetre in the army, inferiority complexes bedeviling those trying to escape the simplest arithmetical calculations, the principle of the molested family, the grimmest spirit manifesting itself at the moment of spiritual creation—such is the unexpected harvest that filled my mind upon completing these first journeys to the USA, where I was absorbed in the study of urbanist phenomena.45

It’s hard to fathom how a painter as wonderful as Caravaggio—whose sureness of construction, steely representation of physical space, emotional intensity, and true bravura make him more Le Corbusier’s match than his opposite—should have brought on such opprobrium. But the architect could not stop ranting:

His case is one for the psychiatrists. Young lady from Vassar, is it in the name of art that you are floundering in this sewer? I believe you are impelled to do so by an unsatisfied heart….

Here are sensitive, ill-constructed souls busying themselves with these splendid twilight decors. The sea withdraws; the sky bleeds to the horizon across the dark green water; ruins are heaped into cenotaphs, the clouds ripped to pieces; stumps of columns lie on the ground; by association, women’s bodies cut into pieces, the black blood streaming from them, birds, a horse of decadent antiquity. Symbols, short-cuts, evocations. What is such a liturgy? What refined, moving, spectral ceremony? What appeal to the past? Is something being buried? It is the past that is being buried, all that has ceased to be. The dead are mourned. Very lovely, all that.

Certainly! But the ceremony is coming to an end. The new world awaits the workers!

The USA of the intelligenzia indulges in such rites. This country which knows only technological maturity is anxious in the face of the future. The American soul seeks refuge in the bosom of things past.46

In this incoherent rampage, Le Corbusier next amplified the effects of saltpeter. The substance that gave a perpetual “spoonful”—Le Corbusier’s term for a nonerect penis—to American soldiers was comparable to the music and dance in Harlem in their effect on intellectuals and socialites, to the work people were forced to do in dismal skyscrapers, to “business” and a lot of other elements of American life that rendered its population, “timid” by nature, impotent.47 His image of American soldiers—the same breed as those robust young men Charles-Edouard Jeanneret had admired during World War I—and of the country as a whole was shattered.

11

Impotence in any form was Le Corbusier’s nightmare. Having thought that in the United States he would find clients and powerful patrons, he had discovered, instead, a neurotic culture of pathetic, defeated people whose lives revolved around the need to earn money. Men were working too hard to support their wives, while American women were “amazons” who dominated their beleaguered husbands.48 These women’s demands for jewelry, furniture, vacations, and other luxuries caused the husbands to die at the age of fifty. He was appalled by the ineffectiveness and timidity of all these creatures who lived as victims rather than celebrants of their existence.

Le Corbusier declared that in American design “a funereal spirit prevails, a solemnity which cannot yet be shaken off.” In this land of inhuman dimensions, in spite of the attempt of Hollywood to lighten life with the comedies of Laurel and Hardy and Buster Keaton, “reality is not so funny as the films. It is serious, overwhelming, pathetic.”49

Although everything was possible in this young country, the absence of an underlying philosophy meant that nothing had been achieved there. Le Corbusier had not disliked a place so much since La Chaux-de-Fonds.

THERE WAS, however, one aspect of American culture that had not let him down. His term for it was “the nigger music.” Jazz embodied many qualities that Le Corbusier held dearest. It was “the soul’s melody joined to the machine’s rhythm. It has two tempi: tears in the heart, throbbing in the legs, torso, arms and head…. It floods the body and the heart.”50

Le Corbusier identified the provision of pleasure through tempo and rhythm with the goals of his architecture. Not only did this American music with the power to make people dance obsess him, but so did the lives of America’s blacks. Focused on both the Pullman porters and slum dwellers, he believed that, however difficult their everyday reality, black people had music that enabled them to enter “the heart’s chapel.”51

The architect had a new hero. Louis Armstrong was “the black titan…Shakespearian…alternately demonic, playful and monumental…. This man is madly intelligent; he is a king.”52 In Boston, he had heard Armstrong perform in a nightclub: “It was absolutely dazzling: strength and truth.”53 For all that Le Corbusier disdained in America, when the values of John Ruskin were made corporeal, he was ecstatic.

12

On December 14, Le Corbusier wrote Marguerite Tjader Harris from the SS Lafayette, the boat that was returning him to France. With his letter, he enclosed a sketch he had made of his lover. The drawing shows her standing on the dock, sporting a hat and a tailored suit that accentuates her impressive height, full bust, and statuesque bearing. The New York skyline is behind her; clearly this was the last vision Le Corbusier had as his boat departed. The caption underneath the drawing reads simply “Au revoir, amie!”54

He had previously sounded the themes of this letter, above all to his parents. Certain terms of adulation for his mistress echoed the praise he had periodically showered upon his mother. But a lot of what he wrote to Marguerite Tjader Harris—the woman he discussed with no one and who in turn kept their relationship secret until well after his death, and whose name never appeared in any account by or about Le Corbusier during his lifetime—reflected a degree of admiration and love he showed to nobody else.

He wrote,

Everything was lovely, clean and careful, dignified and affectionate. Why shouldn’t the heart be entitled to love where it is allowed to open, reveal itself, and receive the maximum of joy and well-being?

The road the heart takes is—step by step—precipitous, headlong, dangerous, and leads to the peaks where something of real life is visible. Why not take a look at life?

I have seen you and not looked, then seen and known, and recognized…. You are strong, healthy, fine and fair. You are open and affectionate. Not closed. Around you the warmest feelings gather. You are strong and gay. Kind.55

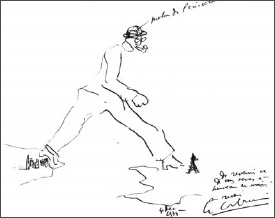

Drawing of the “Piéton de Princeton,” made just before leaving the United States to return to France, with the caption “de revenir et de vous serrez à nouveau la main au revoir Le Corbusier 4 dec 1935”

Drawing of Marguerite Tjader Harris, December 14, 1935

Le Corbusier told the Connecticut divorcée that he could not imagine what New York or the entire trip would have been like without her. He savored his memories of the sea, her amiable mother, the beach shack, the Victorian house, and the roads around Darien.

You have been the peasant-maid of New York, a little Joan of Arc for Le Corbusier rattling in the void. A sustenance.

A kind blond light.

Friend, I thank you. My thanks.56

To no other lover did Le Corbusier express himself with such respect. He had let go of his usual sense of distance; there was none of the condescension of his communication with Yvonne. For the first time, he had met a woman on his own level.

LE CORBUSIER announced his new austerity to Tjader Harris, as if he were a priest who had strayed but would now put his collar back on: “And, now my life will return to its old ways, a believer’s heart, vital and transparent, one I can truly respect.”57 Le Corbusier declared that he would now stop thinking about their affair. Discipline would take over; the legacy of Calvinism, of Nietzschean self-control, would prevail.

For all of his steely resolve, however, his emotions shifted constantly. As if drawn by a powerful magnet, Le Corbusier jumped from that summoning of correct behavior back to his memories of the marvelous tenderness he had experienced with his energetic, warm-spirited lover. Then, in another turnaround, he lapsed into a pathetic image of himself at age forty-eight: “The future does not belong to us. The years pass, and continue to pass. Poor old Le Corbusier, so near Autumn, though his heart is a child’s.”58

Nonetheless, the architect maintained, in secret, his connection not just to Marguerite Tjader Harris but also to her son for the rest of his life.

IN HER LATE-LIFE MEMOIR, Tjader Harris provided a portrait of Le Corbusier with observations very similar to Josephine Baker’s. His lovers saw in him a simplicity and genuineness that eluded the larger public. The divorcée wrote that he “was not a complicated man, not even an intellectual, in the narrow meaning of the word. He lived by his faith and emotions.”59

Both women also understood his single-mindedness and his consuming dedication to his work. Le Corbusier’s American lover wrote, “His desire was to create, to work, to accomplish. Everything in him was united in this intention. If he needed a little relaxation, if he needed affection, it was to work better, afterwards. He cared nothing for a social life, nor for the hundred little subterfuges and gallantries necessary to the pursuit of women. We had found a free companionship without obligations nor demands.”60 She was as remarkable as he was.

13

On Le Corbusier’s first night home after the American trip, Yvonne put a record of American jazz on the gramophone in the spacious, modern living room on the rue Nungesser-et-Coli. He considered it a perfect greeting—as if the beguiling Monegasque knew intuitively what he had liked best on the other side of the Atlantic.

He was content to be back. During the festive time of year he normally detested, Le Corbusier “found the bistros mediocre, yet the sky everywhere above the city, and the grace of proportions and the care taken in the details affords real pleasure.”61 In Paris, at least, there were no skyscrapers to destroy the street and block the sunlight.

In traveling to the USSR and the United States, Le Corbusier had visited the two most powerful countries in the world. In each case, he had embarked as a believer, hopeful to have found the answer and the place where he would realize his dreams of new building types and of the Ville Radieuse. What he had anticipated had not panned out. Now he had to acknowledge that neither country had adopted him as its leader and master planner.

Subsequent events only confirmed his disappointment with the United States. In the following year, Le Corbusier feuded with Museum of Modern Art authorities about unpaid lecture fees and their failure to publish an English edition of La Ville Radieuse, as he had hoped. He had won himself a number of fans in America, but many of the people with whom he had been closely associated there—Alfred Barr and Philip Johnson at the Museum of Modern Art among them—had found him intolerably contentious.

Le Corbusier’s starting point with the United States had been a faith in utopia, the hope of perfection. He now accepted that this did not exist. On the other hand, he had confirmed his love for the woman who best understood both his heart and his genius.