LIV

1

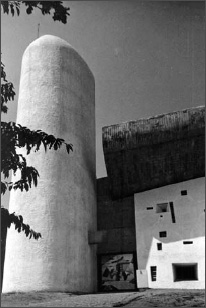

In the spring of 1953, the construction drawings for Ronchamp were completed, and in September the excavating and building began. Because there was no road to transport materials to the hilltop, Le Corbusier had decided to construct virtually everything out of sand and cement that could be mixed into concrete on the spot. The only substantial material that had to be brought in was metal lathing to serve as joists.

The chapel walls were constructed to be nearly four meters wide at the bottom and as narrow as half a meter at the top. Those walls—each a curve, with the south facade slightly concave and the others convex—followed forms calculated for maximum stability. Rather than being perpendicular to the ground, they slope inward, like the sides of a teepee. Aside from providing a dramatic impression, that formation contributed to the structural soundness of the whole.

Ronchamp, view of chapel, ca. 1955

The design facilitated the seepage of light from above that Le Corbusier desired: “An interval of several centimeters between the shell of the roof and the vertical envelope of the walls makes possible the arrival of signifying light.”1 In that single tightly composed sentence about this unusual construction, Le Corbusier invokes music, a biomorphic parallel, the emotional security offered by neat packaging, and the capacity of light to uplift the soul—all of which were priorities for him.

In addition to its many other inspirations, the reinforced-concrete roof was built according to the principles of airplane wings, each with a structure of seven beams linked by parallel ribs. The separation between the two winglike forms was 2.26 meters, a measurement essential to the proportions of the Modulor. The beams of the two wings—each a taut canopy, watertight and with strong insulating capacity in spite of being a mere six centimeters thick—rest on load-bearing struts within the chapel walls. Impeccable engineering was essential to realize the fantasy.

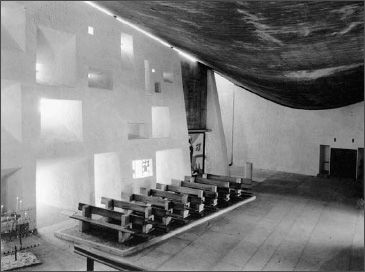

WHAT A VISION had been born from that crustacean’s shell transmogrified by Le Corbusier’s primal instinct to heighten the experience of form and space. The soaring roof looks like a mix of a partially crushed sombrero, a ram’s horn, and a bell clapper; Le Corbusier himself compared its form to a stretched bowstring. Tiny windows are scattered as if by chance in the thick plaster walls. The open-air pulpit and dramatic downspouts seem fictive. The looming towers are bifurcated cylinders with windows that resemble caricatures of noses and eyes as conceived by Klee or Miró. The interior is even more surprising than the exterior, with light arriving in a range of unexpected ways, spaces soaring heavenward just where one least anticipates them, and chapels of startling simplicity.

The concrete of this winged roof is rough and completely without tint. Its raw state declares it a structural material. On the vertical elements within as well as on the exterior of the church, however, a cement gun was used to spray concrete mortar that was then coated in gunite and whitewashed to resemble bright white plaster.

Inside, the floor slopes slightly downhill, as determined by the natural tilt of the land. Thus, after entering the chapel, one descends dramatically toward the altar, walking on cement paving between battens spaced according to the measurements of the Modulor. The altar is constructed of white stones from Burgundy, their color and texture of a beauty that ravished Le Corbusier. He used those same natural blocks for the altar on the outside of the building.

This subtle range of materials and textures is visually and tactilely enchanting. The coarse yet opulent Burgundy stone has a rich roughness. The clean Mediterranean-style whitewash and the bluntly industrial concrete of the roof play against each other. The differing surface treatments also suggest contrasting degrees of weight or lightness that have nothing to do with reality, a demonstration of the ability of art to deceive, and color and dressing to disguise physical reality.

Le Corbusier had kept the statue of the Holy Virgin on the construction site. A member of the Commission of Sacred Art suggested that it should be surrounded by stars. As the props that held up the wall scaffolding were being taken down once the concrete was set, Le Corbusier spontaneously instructed the builders to leave the holes where the supports had been, spaces that normally would have been filled. “Look! You have your stars! There they are!” he declared.2

Interior view of entrance wall at Ronchamp, ca. 1955

The architect then edited the miracle. He designated which openings should remain and which should be filled, with the result that the sunlight makes a halo of bright dots that gives the Virgin in the east wall her perfect crown. This most mechanical of materials and Le Corbusier’s openness to what was haphazard and unexpected thus facilitated poetry and art and religion. The wonder of machinery lay not in the technical mechanism itself but in its service to the soul.

2

On December 9, 1953, just as construction at Ronchamp was going full steam ahead, Le Corbusier sent Yvonne a euphoric anniversary card. He sketched a gnomelike figure shouldering a cornucopia of gifts. The overstuffed sack of presents on its side is perpendicular to the similarly shaped conical cap atop Le Corbusier’s puffy head; the eyeglasses essential to his image are again prominent. Le Corbusier depicts himself with enormous shoulders and sturdy legs; he is a true beast of burden here, and his gait is that of one of his beloved soul-mate donkeys. He grasps at a tall and slender walking staff that is slightly tapered, wider at the top than the pointed bottom.

A number of ten-franc bills are falling out of the cornucopia, while on the top of the walking staff there is a little flag with “100” written on it. We assume that the card accompanied a cash gift. The banknotes appear helter-skelter, but, as the flag indicates, they add up to a precise and balanced total; as with the Modulor, a regulating system has been applied.

This loping self-portrait bears an astonishing resemblance to one of his sketches of the chapel on the hill at Ronchamp. The vessel of presents on Le Corbusier’s shoulders and his funny hat assume the profile of the great roof of the chapel. The walking staff resembles the largest of the towers. The overall proportions are that of the church. The background of mountains and the horizon cause the figure to stand in the landscape much as Ronchamp does. By making his self-portrait the likeness of the church he was offering the world, the gift-bearing Le Corbusier revealed his personal reality. He and his creation were one.

A SECOND CARD FOLLOWED (see color plate 15). Here Le Corbusier shows himself as an enormous and powerful black bird—the ultimate crow—that is yet another image of the church under construction. As it looms over the landscape, the crow’s fully spread wings resemble Ronchamp’s marvelous roof in its command post in the Vosges. It flies above the horizon, looming over a vast cityscape on which thumbnail sketches indicate Notre-Dame, Sacré-Coeur, and the Arc de Triomphe. This time the gift contains two hundred units in a box tied with a ribbon and bow, suspended from the crow’s clawlike feet, which have ferocious talons. The message is as sweet as the crow is forbidding: “With all my affection of 31 years of perfect happiness.”3

The looming roof at Ronchamp with its two equal wings separated by a meticulously measured void was to many people as terrifying as this gigantic bird, but Le Corbusier here suggests a very different interpretation. Even if its face appears at first frightening, the church on the hill should be understood as the image of tenderness and as a bearer of wonderful gifts.

In the note scribbled alongside the drawing, Le Corbusier voiced his desperate wish for his wife to get healthier and happier. He instructed Yvonne, “promise your Le Corbusier, who follows your anxieties hour by hour, that you will wear your white shoes, that you will eat soup, that you will come every day after lunch to join me for a little stroll in the Bois, to get you used to walking again.”4

It is a heartbreaking scenario. Le Corbusier has depicted himself as the image of virility and aliveness. At the same time that he was flying all over the world, realizing his potency in Chandigarh and at Ronchamp and La Tourette, he had to beg his wife simply to take in enough sustenance to stay alive. There was little hope that she would take the daily walks he proposed or that her legs would again function properly.

And even if Le Corbusier declared her to be the source of his unblemished happiness, Yvonne was becoming increasingly difficult. She dressed as a little girl but could comport herself as a hag. The few visitors to the apartment where she lived in seclusion were struck by her “incredible language” as “she insulted Le Corbusier” mercilessly.5 She was hiding her liquor bottles. A true “alcoholic exsangue,” when she fell, she also broke her limbs without feeling the pain sufficiently to know what she had done.

What was needed above all was for her to cease drinking in order to stop the falling. That she might abstain from alcohol was unlikely, but Le Corbusier clung to the belief that her new doctor, versed in the latest advances in medical thinking, still offered hope.

3

During his retreat in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin in February 1955, Le Corbusier told Marguerite Tjader Harris about Ronchamp. It was, he allowed, “an ineffable thing! I believe it to be an apparition from 2000 years ago. From the Christianity which by grace overwhelmed Rome.” Le Corbusier exulted the white inside and out of this structure “beyond dimensions, beyond measurements, alone in the landscape by the miracle of proportion.”6 In the construction shack, he was designing the windows. Again he specified that he would paint them rather than use stained glass, a material he detested. And he was completing the design of the enormous door, composed out of enamel tiles that would be baked at 670 degrees Fahrenheit to fix the colors.

To Tjader Harris, the architect associated his recent operation for varicose veins with the idea of “circulation” for the pilgrims entering or exiting the church and ascribed to different aspects of his existence the same numeric harmony he put into his building: “And in a few days, I’m going to a factory to paint in enamel both sides of the main door. Eighteen square meters, nine on each surface! An enamel door of 9 square meters turning on a central pivot, making it possible for pilgrims to enter and leave to the right and left. I’ve based the design (pentagram) on an altarpiece in the Louvre, a French primitive I fell in love with at twenty (around 1918) and since then inscribed in the depths of my affection. The other day, in the hospital, after a difficult operation, I had noticed the drawing among some photos I had put in my bag to study in the solitude of my hospital room. Foresight, since I was then stripped of 80 centimeters of the femoral vein, from ankle to anus. (I’ve suffered for 30 years from a painter’s (varicose) vein, so-called because some painters put their entire weight on one leg in an effort of mental concentration.) Ten days later I was in India. In five weeks we’ll be finishing Nantes, our second Unité (like the one in Marseille), this one completed in eighteen months. A triumph of organization and will on the part of my studio, particularly the younger members of the staff.”7

In this kaleidoscopic letter where he lopped ten years off his age, Le Corbusier provided a sketch in which he vividly rendered the pile of discarded veins. He also boasted about the High Court in Chandigarh, calling it “a sensational building, striking and brilliant against the background of the Himalayas.”8 Marguerite Tjader Harris was still the person who could best understand both his fortitude in face of hardships and the miracles he had now accomplished.

4

Time was flying, Le Corbusier wrote his mother that March, “at cyclone speed. Evening is divided from morning by nothing more than a fugitive fifteen minutes: not even time to breathe.” Now that he was back in Paris, his tasks at hand were “exhausting. Actually dangerous!” For this reason he had put an end to all social life, was seeing no one, was not showing himself, and was refusing all visitors—he specified each category of social avoidance—and was applying himself to his work alone: “I pay no attention to everything humming and buzzing around me. Silence!”9

The construction of his second Unité d’Habitation was soon to be finished, having been completed entirely by his office crew. In Berlin, the “Fritz”—as he continued to call Germans—were organizing an enormous housing exposition and had given him a prime spot. Then there had been the summons to Chandigarh for Nehru’s inauguration of the High Court on the nineteenth of March.

In this litany of successes to his mother, Le Corbusier did not, however, mention Ronchamp. The omission of the chapel in the Vosges was curious. It was, after all, nearer to Vevey than most of his projects. In many ways, it was to be his masterpiece.

The architect had his reasons for remaining mute.

5

With the sole exception of New Year’s Eve and a second restaurant outing via car, Yvonne had not gone out of the house for six months. Le Corbusier wrote his mother that he was concerned that even under Jacques Hindermeyer’s care his wife was not improving. By April, however, she was benefiting sufficiently from the new treatment to travel to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Le Corbusier wrote his mother from the cabanon that Yvonne would have been happy, if only her health was better, for in their wonderful getaway, “far from snobs and futile arguments,” she was beloved by all “the best people.”10 But there was no chance of abstinence from drinking.

The cold on the Mediterranean coast was so biting at first that even the beautiful sunshine did not mitigate its effects, but then the weather turned soft. The sky and the sea were perfect, Le Corbusier euphoric. Having read in the newspaper that there was snow, astonishing at that time of year, on the lakeshore between Lausanne and Vevey, he wrote his mother that he assumed she was “taking refuge with the sun, Père soleil.”11

In the small studio (“precisely 183 × 388 cm,” he informed his mother), he was now working, simultaneously, on the Governor’s Palace in Chandigarh and on the second volume of the revised Modulor 2: “My lay-out work is terribly exacting, exhausting, absorbing, as any work that is well done must be.”12 He did this work seated on one of two wooden whiskey boxes that he had collected from the sea, which had presumably been thrown overboard from boats. If in earlier years Le Corbusier had been thrilled to be placed at dinner next to people with titles and had sought out the company of anyone with power, now he could afford to deal with humanity according to his own standards and work in solitude. Decent, honest human beings like Yvonne and the Rebutatos were the architect’s personal royalty, unlike the pretenders in Paris, and the monk’s cell for work was all he needed.

6

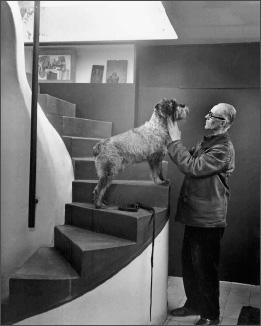

Early one Sunday morning in the middle of May after he and Yvonne had returned to Paris, Le Corbusier took one of his frequent walks through the Bois de Boulogne. On a road lined by chestnut trees, a magpie had fallen out of its nest. Apparently knocked down by a high wind during the night, the wounded creature was lying on the path. Le Corbusier picked it up.

During the rest of his usual hourlong walk, carrying the magpie, he thought about what he had done. At first, he considered himself ridiculous. He did not know how he would find the correct insects with which to feed the poor creature, or what box to put it in. He was afraid that Yvonne would force-feed it. It would be necessary to protect the wounded bird from the dog and cat at home.

But then he reconsidered his action: “No, what I did was right: there are no trivial actions—that’s what I realize every second of my life,” he wrote his mother.13 Half an hour after picking up the bird, he found the nest that had fallen out of a tree. His first thought was that it was not God who had organized this encounter. Rather, Le Corbusier reflected, his eyes—unbeckoned by any other source—had located that nest.

Le Corbusier observed that his soul had been preoccupied by the search for any sort of container, such as a discarded box, with which to harbor the injured bird. Indeed, before he saw the nest, he had found such a box. Then, although he was no longer aware that he was looking for anything, his unconscious mind, which a few moments earlier had been programmed for the discovery of a box, had now caused him to spot the nest. He noted all of these cerebral processes in the account he wrote his mother and Albert.

Le Corbusier put both the nest and the bird into the box. The bird opened an eye. Then, all at once, the creature flew off—only to crash into a streetlight and claw onto it for dear life.

The architect could not get the bird down from the streetlight. He went home, fetched a ladder, returned to the scene, climbed up, grabbed the injured bird, folded up the ladder, and returned home. He went immediately to the roof garden. There Yvonne had her collection of sparrows, which had now grown from forty to between fifty and sixty. Le Corbusier installed the “piaf” on the rooftop structure that housed the top of the elevator. Again, it batted its eyes and flew off, returning to nature.

The sixty-seven-year-old architect concluded, “This situation has its importance!” It symbolized the fleetingness of all experience and the ungraspability of what one thinks one has in hand. “You know the old song: time is merely an endless, terrifying leak,” he wrote.14

With his dog Pinceau du Val d’Or (Pinceau II) at 24 rue Nungesser-et-Coli, ca. 1955. Photo by Robert Doisneau

What counted even more than the rapid flight of time was Le Corbusier’s relationship to the bird’s housing. Having tried to use a box—constructed by an alien species and made of materials completely foreign to a magpie—at least he had then had the wisdom to include elements of the little creature’s indigenous housing. Nonetheless, having used every means at his disposal—his own cupped hands, the ladder—to care for the wounded animal, he had, in the long run, failed to exercise control, however well meant, and the bird had eluded him. Nature had prevailed; he was humbled by its force.

7

At the start of June, Le Corbusier made a quick trip to Ronchamp, his last before its inauguration. For two days, he was on his feet there from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., installing the windows and altars.

When he got back to Paris, he wrote his mother that he was anticipating eighteen thousand people at the opening ceremonies. On the other hand, it was not necessary for her and Albert to attend. Le Corbusier attempted to explain why: he would not be available to them during the proceedings, and he was going to flee the scene the moment the official acts were over. He could not imagine, besides, how all those people would reach the church on the one footpath. He also advised that it was a longer distance from Vevey than they realized. He proposed that his brother and mother see the new chapel in July, instead. He would happily meet them there for such an encounter.

None of these was the real reason Le Corbusier did not want Marie and Albert on the scene.

In the same letter where the architect spun out his fatuous excuses, he continued, “One request in this matter: suppress all declarations like: we Protestants; wir schweizer; etc. I’ve made a perilous work. Rome has its eye on me. The cabals need only a spark.”15 He did not want to disabuse anyone of the false assumption that he was Catholic.

Le Corbusier became even more adamant in a letter he wrote his mother and brother on June 23, the day before he left for the opening. Reminding them that they would see Ronchamp in July, he asked, as if he could not remember, if he had already written them on the subject of their discretion. In case he had not, he now instructed, “Don’t go shouting: 1. We Protestants…2. We, Le Corbusier’s mother and brother…3. We Swiss…etc. Forgive me, but understand: there will be eulogies…. You understand, don’t you, or do I have to send smoke signals???”16

Le Corbusier told them about an “imbécile” from the Chicago Tribune who had asked him if to build Ronchamp it was necessary to be a Catholic. The architect replied, “Foutez moi le camp!” On the edge of panic about what his mother and brother might reveal, he snapped, “Like the American journalists, you specialize in insolent questions!”17

He instructed Marie and Albert that surely they did not want to make his life any harder. The upcoming inauguration of his building at Nantes—scheduled for July 2—was bringing out the foxes and jackals; he begged for support and sympathy.

He was, he told them, in a state of exhaustion. He had been summoned by telegram to help advise on the new capital of Brazil, but it was all too much for him. Yvonne was even more unwell—too incapacitated to attend the Ronchamp inauguration. He now gave arthritis as the cause.

Two days after he wrote that entreaty, the crowd at Ronchamp cheered Le Corbusier as one of the creative giants of the twentieth century. But Charles-Edouard Jeanneret was still determined that his mother and brother recognize the difficulty of his lot in life. He was counting on them, for once, to go easy on him—and to guard their silence.