LVII

1

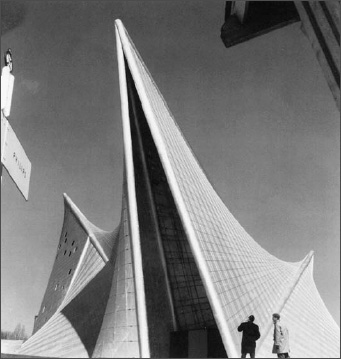

One of Le Corbusier’s most provocative buildings no longer exists except in photographs. The Philips Pavilion, erected for the 1958 Exposition Universelle in Brussels, was a multifaceted structure that resembled gigantic tents impossibly interlocked, simultaneously collapsing and inflated.

Here, too, Le Corbusier had initially said no to the project. Early in 1956, representatives from Philips had approached him with the proposition; compared to all he was working on in India and elsewhere, a 6,500-square-foot space was not of much interest. Then Philips, a leading manufacturer of lighting and sound equipment, assured Le Corbusier access to all the latest technology that would enable him to integrate the most advanced sound and lighting devices into his architecture.

With that idea in mind, Le Corbusier was inspired one Sunday morning walking his dog in the Bois de Boulogne. He used the third person to describe the arrival of the idea in his mind: “He sees several notions gradually appear: light, color, rhythm, sound, image…psychophysiological sensations: red, black, yellow, green, blue, white. Possibility of recalls, of evocations: dawn, fire, storm, ineffable sky…. Measurement of time: rhythm, elegy and catastrophes.”1 It would be an “electronic poem.”

Le Corbusier conceived of a carefully programmed spectacle through which visitors would walk over a prescribed period of time inside an organic structure. In ambient darkness, there would be a violent performance of colored neon lights and images projected on the walls. A sound program by Edgard Varèse would accompany the visual shifts. The total visit would take eight minutes, during which seven minute-long films separated by brief interludes of darkness would be shown in sequence.

Varèse’s involvement was central to the architect’s thinking. He wrote the composer, “I hope this will please you. It will be the first truly electric work and with symphonic power.” Varèse replied, “I find your project superb…. I accept with great pleasure your offer of collaboration…. Like you and the Philips company, the only thing in which I am interested is to give birth to ‘the most extraordinary thing possible.’”2

The Philips Pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1958

When the people at Philips voiced fear about the effects on the audience of the composer’s unusual electronic score, Le Corbusier supported his fellow modernist with the loyalty he expected others to display for him: “There can be no question, not even for a minute, that I will renounce Varèse. If that should happen, I will withdraw from the project. This is a very serious matter. My reputation is at stake as is that of Philips. My life has been a succession of efforts and battles. The UN in New York was built on my plans (stolen)…. I have written more than 40 books.”3

Le Corbusier convinced his clients to accept Varèse’s combination of percussion and the sounds of machinery: “rattles, whistlers, thunders and murmurs”—as they were eventually characterized by the New York Times critic, who called the building “the strangest exhibit at the Brussels World’s Fair.”4 Sirens of the type used on ambulances and police cars vied with screeches that were like the cries of tropical birds on a desert island and with deep animal roars. By calling on Edgard Varèse, the architect had summoned everything he believed in: bold modernism, the timeless forces of the universe, and the spirit of the automobile, all combined.

2

After engaging Varèse and conceiving of the pavilion as a building without a facade, to be made from the inside out, accommodating Varèse’s sequence of sounds and allowing for the seven films, Le Corbusier assigned much of the design process to Iannis Xenakis, one of the younger architects on his staff. Xenakis, born in Romania in 1922, had studied engineering before fighting for the Greek resistance; after his radical politics led him to flee to France in 1947, he had been hired to work at 35 rue de Sèvres. Since 1951, he had been concentrating on l’Unité at Nantes and then on La Tourette.

Iannis Xenakis’s lack of formal training in architecture in no way bothered the master. Moreover, the young man, handsome in spite of a severe face wound that cost him his sight in one eye, was a great advocate of the Modulor. Also a composer, he had written the seven-minute-long “Metastasis,” performed by sixty-one instruments, with the Modulor and its proportions and divisions as its basis. Xenakis wrote two minutes of music for the Philips project, to be played between presentations as one audience left and another filed in.

While Le Corbusier was in India, Xenakis came up with the scheme of the building as it was constructed, sketching the hyperbolic paraboloid forms and making a model in which he used piano wire and thread. Guided by the structure of shells, Xenakis unquestionably followed Le Corbusier’s lead and accepted the idea that the requirements within the container must determine its external appearance, but then he devised shapes far from Le Corbusier’s initial idea.

In July 1957, Le Corbusier visited the Philips headquarters in Eindhoven to learn more about the technical requirements for the Electronic Poem. During his August holiday in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, he ruminated on it, and in September the model for the pavilion was published in the magazine Combat. The design was attributed solely to Le Corbusier.

Xenakis was appalled. He wrote Louis Kalff, the art director at Philips, demanding that his name appear alongside Le Corbusier’s. Kalff turned him down, explaining that Philips had commissioned Le Corbusier, who had conceived and developed the plan, which Xenakis had then simply sheathed. Attribution would be given to Philips, Le Corbusier, and Varèse—and no one else. Kalff assured him, however, that articles and histories of the building would acknowledge Xenakis’s role.

Le Corbusier became enraged that Xenakis, his employee, had been directly in touch with a client without his permission. The master advised Kalff to “take a panoramic glance” at the six volumes of his Complete Work. Kalff would discover that Le Corbusier had never “personally drawn a line on a drafting table. Consequently I authorize you to agree that it was not I who designed the palace of the League of Nations nor the Centrosoyuz nor the Mundaneum nor the World Headquarters of the United Nations in New York nor the Villa Savoye nor the villa at Garches nor the plan for Bogotá nor the plan of Meaux nor the chapel at Ronchamp nor even the apartment in which I live on rue Nungesser-et-Coli. However, the following fact will appear curious: among the 250 architects who over thirty years have formed the studio at 35 rue de Sèvres, not one has appeared on the professional horizon…. All this is quite troubling, don’t you think?”5

Le Corbusier then resorted, as usual when he was piqued, to downplaying the conflict as if everyone other than he was simply being childish: “It frequently happens that the team is convinced that it is driving the carriage. Let’s not give this incident greater importance than that of a violent outburst of a temperament itself violent.”6

FOUR DAYS AFTER WRITING to Kalff, Le Corbusier decided that the wording engraved in concrete on the front of the pavilion, to appear in all future publications, was to read “Philips–Le Corbusier (coll. Xenakis) Varèse.” That this would make sense to the general public is unlikely, but the master had spoken. Xenakis was sufficiently satisfied to continue working at the Philips project, on La Tourette, and then on the stadium in Baghdad.

But the affair was not over. Following the summer holiday in August 1959, Xenakis and two of his closest colleagues in Le Corbusier’s studio returned to 35 rue de Sèvres to find the doors locked and their keys no longer working. Shortly thereafter, Xenakis received a letter that begins, “Modern architecture triumphs in France; it has been adapted. Today you may find a field of application for everything which you have acquired by yourself as well as through your work with me.”7

Xenakis was shattered. A year later, when he and Le Corbusier met at the inauguration of La Tourette, in an astounding about-face, Le Corbusier asked him to return to 35 rue de Sèvres as architect in chief. Xenakis replied that he now only wanted to compose music. He never again practiced architecture.

3

At the start of 1958, the town of Poissy insisted that the Villa Savoye be torn down so a school could be constructed on the site. Since French law did not permit “historical monument” status for buildings when the designers were still alive, there were no legal grounds for saving Le Corbusier’s masterpiece of the 1920s. Distinguished supporters from all over the world sent telegrams, but the bulldozers were scheduled.

In March, at the last moment, André Malraux stepped in. It was only the intervention of the influential writer that spared the twentieth century’s answer to the Parthenon from the wrecker’s ball.

Le Corbusier was in one of his tumultuous periods. The opening of the Philips Pavilion took place on a later date than Philips had intended because of delays caused by his incessant modifying. Then, following the official event on April 22, 1958, the pavilion was promptly closed. The Electronic Poem was a technical disaster.

Numerous time-consuming adjustments were necessary before the multimedia event was ready for the public. But once it opened, it was an exhilarating spectacle, even though it needed constant tinkering throughout its brief existence. The films showed the history of human civilization and addressed threats to the future of the world. There were images of prehistoric man, concentration-camp victims, New York skyscrapers, and other elements that provided an encyclopedic overview of humanity. Le Corbusier had invented a new art form that simultaneously surrounded the viewer and assaulted his or her senses head-on. It presaged the video and installation art of recent years.

The titles of the seven short films were “Genesis,” “Matter and spirit,” “From darkness to dawn,” “Manmade gods,” “How time molds civilization,” “Harmony,” and—the longest of all, running nearly two minutes—“To all mankind.” Each segment flashed sequences of images that lasted only a second. To the sound of a gong and then Varèse’s score, the shots for “Genesis” jumped from a sparkle of stars in the darkness to a bull’s head to a matador to a man and bull in combat to a Greek statue to a woman lying facedown to the same woman staring into a skull. “Matter and spirit” was a rapid cascade of images ranging from a nearly naked African woman to a woman from a Courbet canvas to a dinosaur skull to the rest of the dinosaur’s skeleton to a monkey. The other films had fleeting shots of tribal art, the skeleton of a human hand (single and then in duplicate), horrific corpses from Buchenwald, close-ups of Chartres, religious art by Giotto, and a Buddha. Jumping between despair and hope, between destruction and creativity, between western and eastern traditions, this imagery, in a panoply of colors, touched the extremes of existence. The haphazardness of one’s birth was clear—one might as easily have been born as another species or in a totally different culture.

At the end of the Electronic Poem, Le Corbusier gave hope for this complex universe he had just presented at breakneck speed. The solution lay in his own work. He showed his projects for Paris and Algiers, the Unités d’Habitation in Marseille and Nantes, the High Court at Chandigarh, his plaster model of the Open Hand, and his drawings for the Modulor. As an epilogue, he presented people of all ages, with, at the very end, a baby’s head next to the profile of someone we assume to be its mother, looking on tenderly.

THE EIGHT MINUTES during which five hundred visitors at a time circulated through the mélange were extraordinarily intense. While this rich subject matter flashed by, projectors superimposed simplified abstract images across it. And within the space of the pavilion, sculptural forms were illuminated with ultraviolet rays.

More than forty years after Le Corbusier had seen Parade and read Apollinaire’s exegesis on “L’Esprit Nouveau,” he had joined Cocteau, Picasso, and Satie in making a new form of collaborative performance, to which he had added the element of the latest in pioneering technology. The Electronic Poem was a means of combining operatic effects with modern engineering, two forms of human expression that Le Corbusier especially esteemed.

During the eight months that followed the public opening on May 2, about one million people flocked in, most of them greatly impressed, even if the theoretical points were often lost on them. Le Corbusier was pleased, deciding that the endless technical problems and delays, as well as unresolved issues concerning reproduction rights for some of the photos, were irrelevant. The masses were enjoying themselves, which was what counted.

The architect was, however, annoyed with the response of the corporation that had sponsored the undertaking. In July, he accompanied a bill with a letter to Kalff saying, “I’ve never received a friendly word from your Committee Director about the enormous effort I made on the occasion of your Pavilion. This is an instance of human ingratitude, pure and simple. When an architect has made a building, the client pays him a lamb chop or a veal cutlet when the work is done and gives him a little smile, even if the latter has to be a little crooked.”8

Nonetheless, Le Corbusier regarded Kalff as one of those rare characters from the corporate world who was enlightened. The architect applauded the Philips art director as having “committed himself to this enterprise totally, calmly, good-humoredly, concealing his anxieties, standing up to the unknown, incurring expenses, taking responsibility for everything, smiling at his purveyors. I insist on informing the Philips directors that M. Kalff is one of those Dutchmen, patient, persevering, trusting, courageous, who have bestowed upon their country so splendid a history. Each of us went about his tasks with his nose to the grindstone, forgetting perhaps to appreciate the fact that someone was overseeing everything without respite.”9 If Xenakis had overstepped the limits, the man who had enabled Le Corbusier’s vision to become reality was a hero.

4

The electronics company had initially considered reconstructing its pavilion permanently in Eindhoven as a corporate museum following the eight months at the fair. But the expense proved too high, and the vibrant creation was destroyed quickly by a wrecker’s ball on the afternoon of January 30, 1959. Today there remains a splendid book about it by Le Corbusier and Jean Petit, a recording of the Varèse composition, and a film. The recording fails to capture the effects of the tapes and various noises projected from all around. But what remains is the composer’s statement of what he achieved thanks to Le Corbusier’s concept and tenacity: “For the first time I heard my music literally projected into space.”10

Varèse also wrote, “Trust that I won’t forget the expression of solidarity by one who doesn’t let his pal down.”11 The composer felt as sustained by Le Corbusier as Xenakis felt betrayed.

5

While crowds in Brussels were queuing to experience the Electronic Poem, the architect met quietly with the stonemason Salvator Bertocchi in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin to work on a tomb for his wife’s ashes in the local cemetery (see color plate 26). Bertocchi’s son had been Yvonne’s godchild; the mason had warm memories of her.

Le Corbusier and Bertocchi worked together for a week. The burial ground was on a hill, three hundred meters higher than the little cabanon. It was necessary to use a mule and human shoulders to bring in the heavy materials. Le Corbusier was immensely grateful to Bertocchi for his aid with the ancient tasks of carting and cutting.

At the end of June, Le Corbusier returned to Paris. On July 1, he went to Père Lachaise to collect the urn with Yvonne’s ashes. With Ducret, now more than ever one of his favorite young architects in the office, and Ducret’s wife, Germaine, he drove the thousand-kilometer journey south, across most of France, to Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Then, on July 3, at 10:00 in the morning, Robert Rebutato and seven of Yvonne’s friends, local people about her age, met in the graveyard in front of the tomb Bertocchi and Le Corbusier had made. The cover was lifted, and the urn placed inside. A single bouquet of flowers stood alongside the container with her ashes. They came from Henri, the office boy at Le Corbusier’s studio, who had become Yvonne’s confidant in her last years.

Once Le Corbusier and Yvonne’s friends had walked back down the hill, he felt at peace. He wrote his mother and brother, “And now things are in order, the order of things. I have a feeling of quietude, telling me: She is at home now. A thousand kilometers and back: total two thousand. Le Corbusier’s age 70 years!!!”12

The architect had more to say; he always did. Having appeared to achieve resolution with these round numbers, he used up the remaining space on the paper, filling the tiny margins, to report on his work problems.

The situation was changing in Chandigarh, he explained. Pierre had encountered enemies there—“narrow-minded bastards!”13 Le Corbusier knew he should return there and also travel to Baghdad to work on his stadium, but the temperatures in these parts of the world in summer were ferocious.

In minuscule handwriting, Le Corbusier wrote that he would pay for Albert to go to Brussels to visit the Electronic Poem. Finally, he scrawled the last piece of information: next to the container of Yvonne’s ashes, there was space for his own.

6

Le Corbusier went back to the cabanon in solitude that August. He was exhausted and in need of silence but content because he had won his battle with the engineers at Chandigarh and prevailed in having his ideas put into effect on the buildings still under construction. Nehru had again been his savior.

He wrote his mother on August 23, “We’ve got rid of the sons of bitches. But it was intoxicating. And ahead of you, dear Maman, crushing tasks and endless battles.”14 While Le Corbusier vacationed on the Mediterranean coast, his mother was mountain climbing and hiking to summits and glaciers. Addressing her as “worthy wife of an Honorary President of the C.A.S. [Swiss Alpine Club],” he wrote, “I want you to know of all my affection, all my admiration, all my respect. I think of you every day of my life.”15

He also let her know that he had turned down trips to Rio, Stockholm, and Copenhagen, but he was overjoyed that he was going to be visiting her. Then he proferred strong advice: “What luck that you have your Albert beside you! A real stroke of luck. You must do as he says now and then, when you must. Dearest Maman, you used to exhort us to be good. Let me ask the same of you now. Be nice to those who serve you. Care for them. Love one another (as you deserve): the most beautiful words ever spoken.” This last bit of counsel, of course, had been his father’s final words more than thirty years earlier. “Above all be kind and tolerant to the people around you,” he concluded.16 The irony of those words coming from the man who would secretly change the lock at 35 rue de Sèvres was lost on him.

7

The Japanese government commissioned Le Corbusier to build a museum in Tokyo because a rich Japanese businessman, Kojiro Matsukata, who lived in Paris, had amassed a major Impressionist collection, which had been seized by the French government during World War II. The Japanese had negotiated the return of the collection with the proviso that it be housed in a new structure in the park where several major national museums already existed. Matsukata’s holdings would become part of a National Museum of Western Art, with Impressionism merely the starting point. The notion of the growing collection gave Le Corbusier a chance to move forward with the design of a square spiral museum, intended for infinite growth expanding outward from a central core, on which he had been working for a quarter of a century. Constructed between 1957 and 1959, it was his first and only project in the Far East.

The building realized the architect’s ideal only in part. There is a nearly square court at the center, around which a sequence of galleries was wrapped at higher levels. The Impressionist pictures were to be in the middle, and Le Corbusier acted as if the building could keep growing, to accommodate an ever-expanding encyclopedic collection. That concept did not connect with reality, however. The result is a distinguished structure but does not allow for easy additions.

Two Japanese architects employed at the Paris office detailed the building so that it appeared somewhat indigenous in Tokyo, not like a foreign impostor. Fulfilling the same goal Le Corbusier had in India of wanting his architecture to reflect local culture, he adapted to Japanese taste by using wooden molds for reinforced concrete that looked as if it were composed of wood fibers. He also introduced tiny green pebbles into the concrete as a bow to Japanese aesthetics, and he deliberately gave the building certain Zen-like qualities. The rectangular block on pilotis recalls many of his structures going back to the 1920s, but there is a new placidness—an impressive mixture of strength and quietude. Its simplicity and grace make this voice of the west at the heart of Tokyo a welcome blending of traditions.

In his Complete Work, however, Le Corbusier’s callousness is seen to rival his astuteness. He described the interior arrangements as “forming eaves in the shape of a swastika. The swastika keeps leading the visitors back to the central point of the museum and allows them to descend the ramp toward the exit. At each of the arms of the swastika, there are museum halls on the same level.”17 His obsession with the physical functioning of a structure and his concept of abstract visual harmony seemed to give him a special permit to ignore the hideous symbolism of the form he named three times. Even though in India, as in Japan, the swastika traditionally represented the sun, its recent associations were unavoidable. Le Corbusier’s use of gravel and his harmonic design conjure the most sublime and peaceful rock gardens of Kyoto, but inside his museum he willingly sent visitors on a course of right angles that recalled the goose step.

8

The inauguration of Le Corbusier’s Brazilian Pavilion, a residence not far from his 1933 Swiss Pavilion at the Cité Internationale Universitaire, also took place in 1959. At the event near the periphery of Paris, the architect and various dignitaries had to wait for the arrival of André Malraux, who was late. Once Malraux arrived, he took time getting to the podium, stopping to shake hands and chat with various people. Le Corbusier stood erect without moving. When Malraux reached him, the photographers and journalists swarmed around both of them.

As the architect and de Gaulle’s appointee walked into the new building, crowded by the press, Le Corbusier was recognizably in a rage. He wanted Malraux to himself. He gripped the minister’s arm and forced him into the small elevator, closing the door before anyone else could squeeze in. Then Le Corbusier stopped the elevator between floors. No one knows what was said, but there was no question that this time it was Le Corbusier, not Malraux, who had altered the pace of the proceedings.18

9

The aging Le Corbusier remained hell-bent on the idea of completing the sort of urban scheme that he had championed for the past forty years—even beyond the scale of Chandigarh. The will to achieve some version of the Plan Voisin and instigate his urbanism in Paris became the hope that could keep him alive now that Yvonne was gone. Two years had passed since her death; it was as if the completion of that mourning period allowed self-resurrection. And so, in October 1959, he wrote to Gabriel Voisin.

The two men had not seen each other for thirty-four years, but Le Corbusier still admired the industrial pioneer who had applied aeronautic techniques to the construction of prefabricated houses, and he addressed him as “Mon cher ami.” His effusive letter was specifically prompted by the publication of The Three Human Establishments—an elegant volume, brought out by Jean Petit’s Editions de Minuit, that was a grand summation of Le Corbusier’s ideas on urbanism and how people should live. Le Corbusier explained to his former patron that the Plan Voisin was the basis of many of the ideas that had flowered in his book.

Le Corbusier informed Voisin, “The sites and the working conditions of machine civilization are now appearing, and—O miracle—they emerge from contingency itself: the world is changing, the world has changed. The page will be turned; if it fails to turn, disaster. But it will turn!”19

Le Corbusier was not one to have forgotten a good deed any more than he ever forgave transgressions against him. He delighted in pointing out that “the Voisin Plan” was infinitely more mellifluous than “the Peugeot Plan,” “the Intransigent Plan”—named for the popular French newspaper of the twenties—or “the Citroën Plan” would have been. He recalled how the industrialist had given him the twenty-five thousand francs that had made possible the Pavilion de L’Esprit Nouveau. The 1925 pavilion had been destroyed, but its ramifications had been monumental. Le Corbusier reminded his patron that this structure had also housed a residence that was the model for the apartments that had since been realized in Le Corbusier’s buildings in Marseille, Rezé, Berlin, and Briey. Thus, Voisin’s support had given birth to a type of housing now inhabited by 6,500 people.

Le Corbusier fervently believed that a few brave individuals had the power to change all of human history; he and Gabriel Voisin were among them. With the Pavilion of L’Esprit Nouveau, he had achieved the most perfect marriage of “efficacy” with “temerity.”20 But it and its offshoots were only the beginning. The promised era was still to come.

10

In The Three Human Establishments, Le Corbusier both recapitulates the ideas of a lifetime and puts them in a form that he was convinced made them more realizable than ever. The volume is an elegant, square object. Jean Petit was Le Corbusier’s best publisher, his books aesthetically in concord with their contents. The Three Human Establishments opens with pages printed in the luminous, rich greens and blues of the windows at Ronchamp. A drawing of an immaculately designed tree, illustrating the mathematical harmony intrinsic to nature, follows. The tree is accompanied by the statement, “You must always say what you see, especially (what is more difficult) you must always see what you see.”21

That same tree reappears in larger form a few pages later, next to a quotation from Plato that concludes, “The most beautiful and the highest of all the forms of wisdom, Diotima adds, is the one used in the organization of cities and of families; it is called prudence and justice.” Le Corbusier next cites Rilke quoting Cézanne on the horrors begat by modern industry and on the destruction of the natural world: “Things are going badly, life is terrifying.” Le Corbusier disagrees: “Yet life will always be the stronger. You must understand this and not proceed against life.”22

Le Corbusier then explains that, as an alternative to the dreadful suburbs and garden cities that have wreaked havoc on the way people live, his own “Green City”—with buildings on pilotis and an intelligent circulation system separating automobiles and pedestrians—would give priority to “Sun. Space. Greenery”: the essential elements of human existence.23 Agriculture would flourish, people would work and live together harmoniously, and true unity would prevail.

Whether out of naïveté or blindness, Le Corbusier still believed he might exercise total control over all issues of human habitation and that the world would be better off with new cities designed according to his master plan.

11

On September 10, 1959, the Swiss paper L’Impartial did a major feature on the alleged hundredth birthday of Le Corbusier’s mother. The nearly seventy-two-year-old architect, the article explains, had just arrived from India, having traveled all night to be at the birthday celebration.

“There’s the young lady!” he is quoted as saying. “La jeune fille” was then led to the piano, where she played a few chords. Local children sang the Neuchâtelene hymn in her honor, after which her sons ran around to find tables that could be set up for an impromptu lunch. Marie Jeanneret is taciturn and droll: “‘But you still see the lake from your bed, dear Madame!’ an old friend said to her. ‘When I’m in my bed, Monsieur, I sleep.’”24

On February 15, 1960, the great exemplar of vitality and fortitude died, at what was really the age of ninety-nine. She had been ill a brief two months. The Geneva paper added that she died in her “aluminum” house built by the world-famous Le Corbusier and was also survived by her “second son,” Albert—an error that must have pleased the younger brother immensely.

With his brother and his mother for what was said to be Marie’s hundredth-birthday party

THREE DAYS AFTER the death of their mother, Le Corbusier wrote Albert a letter:

Dear old boy. The black car covered with flowers, with rosy little Maman in her coffin inside, has left on the East Road, miraculously empty of cars, there having been a heavy snowfall, the snow now falling silently. And the hideous red “TOTAL”—the gas truck—has arrived; it had to slow down and line up behind Maman. And everything was hidden and finished in a winter silence as total as in the mountaintops.

All that was simple enough. The two bare-headed brothers saw their mother departing. A mother one hundred years old whose laughter they had been hearing for over 70 years.25

Having been present as well, Albert was not learning anything he did not already know. But a dream Le Corbusier recounted was new to him. It took place “on the Jolimont pier, papa and I arriving in a cloud of steam, young Maman waiting for us in a pink dress and a flat pink hat bristling with artificial pink flowers. Greetings, Albert, from Your Edouard.”26

Le Corbusier illustrated this missive to his brother with a drawing of an elegant young woman, tall and buxom, in a hat. She looks nothing like the person in the hundredth-birthday photos. Rather, she resembles Marguerite Tjader Harris as Le Corbusier drew her on the New York pier.