The author aged 9, in Exeter Museum, talking for the first time about becoming a British Museum curator.

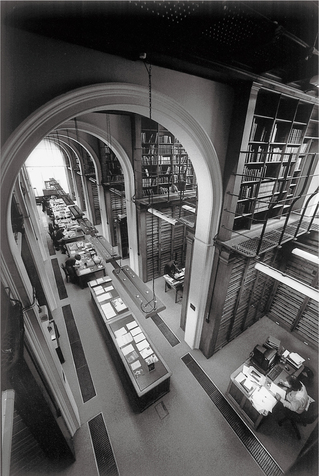

The Arched Room library in the Middle East Department of the British Museum, where 130,000 cuneiform tablets are housed.

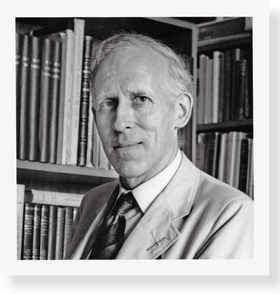

Professor W. G. Lambert, as encountered by the author in September 1969.

Leonard Simmons in Egypt, at the time he was collecting curios, among which this Christmas card can be included.

Douglas Simmonds as a boy with the cast of Here Come the Double Deckers.

Douglas Simmonds with a Mesopotamian hero in the Louvre.

(picture acknowledgement i6)

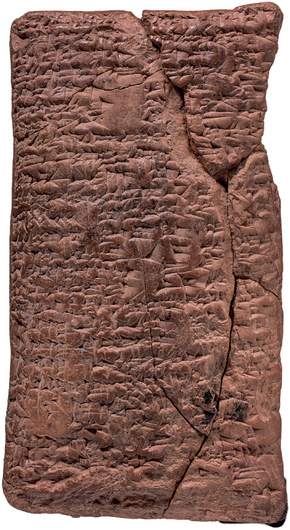

The Ark Tablet, front view.

The Ark Tablet, back view.

(picture acknowledgement i8)

A Sumerian reed hut, or mudhif, as depicted on a stone trough of about 3000 BC.

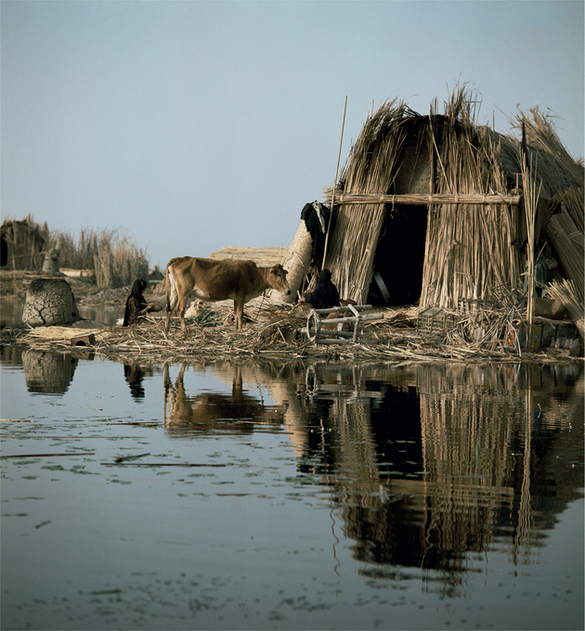

The characteristic and timeless landscape of the southern marshes in modern Iraq.

Reeds, water, man and livestock in harmony in a 1974 photograph taken in the southern Iraqi marshes.

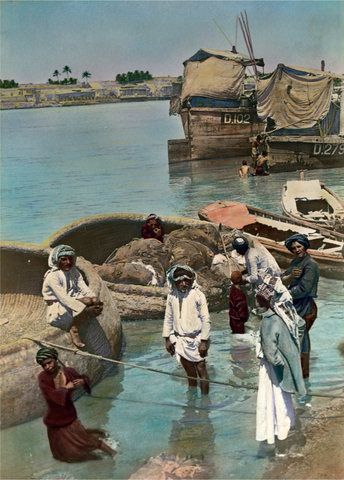

Coracles in use, Iraq, 1920s.

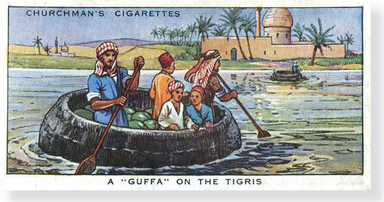

The coracle to capture the imagination of boys as part of the Churchman cigarette card set entitled Story of Navigation.

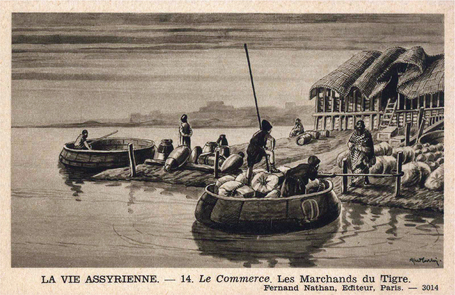

An artist’s impression of ancient Assyrian riverside life.

A model of a traditional coracle from Iraq; the bead and shells are to promote good luck and are also found on full-size coracles.

A seventeenth-century view of the animals waiting patiently to embark, by the Flemish painter Jacob Savery.

This sixteenth-century drawing by Hermann tom Ring gives a good idea of the practicalities involved when it actually came to boarding.

The flood as depicted by Frances Danby, first exhibited in 1840, and a striking canvas.

An Ottoman Turkish miniature with the prophet Nuh in his Ark.

Noah sends out his raven and his first dove in a mosaic from St Mark’s Basilica, Venice, eleventh-century.

The Tower of Nebuchadnezzar’s Babylon, as visualised by an unknown sixteenth-century Flemish painter.

The Babylonian mušhuššu dragon, sacred to the God Marduk, that bedecked King Nebuchadnezzar’s royal walls at Babylon, probably modelled on a giant and carnivorous monitor lizard.

The traditional view of the Judaeans grieving at Babylon, as described in Psalm 137. But, as shown in this book, much happened after the first tears dried …

The Babylonian Map of the World, front view: the world’s oldest usable map.

The Babylonian Map of the World, back view: an old photograph of the hard-to-read triangle descriptions.

The profile of Mount Pir Omar Gudrun, near Kirkuk, northern Iraq.

An eternal icon: a rainbow over Mt. Ararat hidden by storm clouds; seen from Dogubeyazit, Turkey.

Gertrude Bell’s view from Mt. Cudi Dagh.

The twin peaks of Mt. Ararat, irresistible to romantic painters.

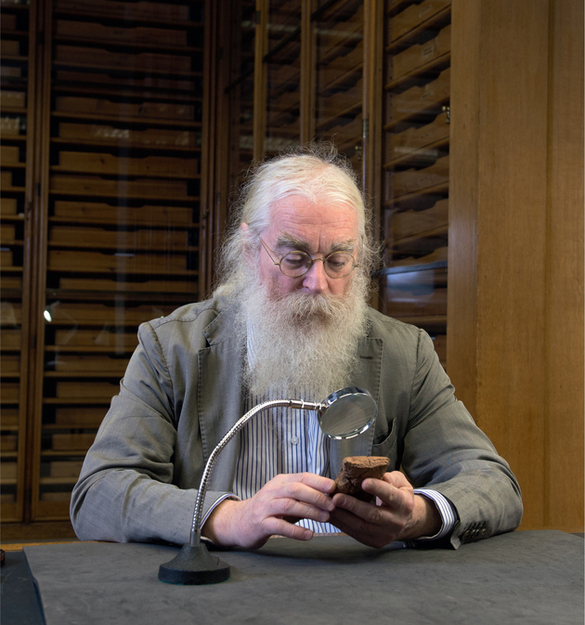

The author battling with broken Ark Tablet signs in the British Museum.