How many miles to Babylon?

Three score miles and ten.

Can I get there by candle-light?

Yes, and back again.

Anon

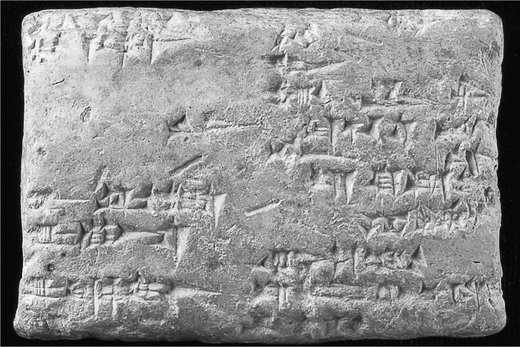

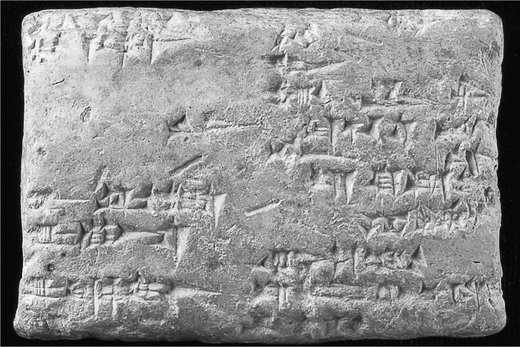

We ought, being plunged in at the deep end, to consider without delay which part of the world has provided our cuneiform tablets (for they do not, as I think my old professor secretly believed, grow in museums), and hunt for the ancient Sumerians, Babylonians and Assyrians who produced them. At the same time there is the important question of what the old Mesopotamians actually wrote.

The cuneiform homeland is identified under a single, resonant name that in the normal world usually lies buried somewhere at the back of the mind: Mesopotamia. Such a resonant name is due to Greek; meso means between, and potamus means river (hippopotamus, to the Greek mind, is a ‘river horse’). There was a period when junior-school teachers drew the rivers in question on blackboards for their pupils, Euphrates to the left and Tigris to the right, all the while happily reciting How many Miles to Babylon? Since the First World War, however, the once familiar name Mesopotamia has been altogether supplanted by that for the same territory today, modern Iraq. The very names of those rivers are half as old as time, recognisable in the unfolding sequence of languages that encapsulate Mesopotamia’s history: buranun and idigna in Sumerian, purattu and idiqlat in Babylonian, perat and hiddeqel in Hebrew, euphrátēs and tigris in Greek, and furāt and dijla in Arabic.

Like the Nile in Egypt, the twin rivers Euphrates and Tigris were the very lifeblood of ancient Mesopotamia. The fertility and wealth that they bestowed on the world’s most expert irrigators had far-reaching consequences, for ancient Iraq became a world stage for the interplay of discovery, invention, trade and politics. We do not know who got there first to harness the waters. Certainly the Sumerians – known best for the Royal Graves that Sir Leonard Woolley uncovered at their capital city, Ur – were early. It is they who, most probably, made the first moves towards writing well before 3000 BC, and it is their language, as we have seen, which was the first to be recorded in the developing cuneiform script. With the advent of Mesopotamian writing, prehistory came to an end and history – acknowledging events and depending on records – became a meaningful term.

Today we know a surprising amount about ancient Mesopotamia. In part this is, of course, due to archaeology, which can analyse graves and architecture and pots and pans, but a deeper understanding of a vanished culture depends inevitably on its written documents. It is from these that we can outline their history and populate it with characters and events; we can observe the populations at work in their daily lives, we can read their prayers and their literature and learn something of their natures. Those on the trail of ancient Mesopotamia through their documents are blessed in their choice of writing medium, for even unbaked tablets of clay can last intact in the ground for millennia.

(The fortunate archaeologist who finds tablets on his excavation will encounter them wet to the touch if they are unbaked, but they will harden sufficiently in the warm, open air to be safely entrusted to the impatient epigrapher within a day or two. It is exciting beyond words to find one of these things actually in the ground, to harvest it like a potato and read it for the first time.)

This survival factor means that the widest spread of documents survives, state and private, much of it ephemeral and never intended for eternity. Startlingly, most of the cuneiform tablets ever written – if not deliberately destroyed in antiquity and not as yet excavated – still wait for us in the ground of Iraq: all we have to do is dig them up one day, and read them.

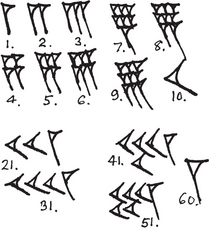

Digging actually started in the 1840s, and cuneiform tablets were soon forthcoming in great number, long before anyone could understand them. The motive behind the first expeditions was to excavate in the territory where the events of the Bible had been enacted, with the principal idea of substantiating Holy Writ. Excavations were carried out under permit from the Turkish Administration which at that time provided for the export of the finds to London. It was this reality that led to the decipherment of Akkadian cuneiform and the development of the field of Assyriology. To any right-thinking individual the decipherment of cuneiform must rank among the great intellectual achievements of humanity and, in my view, should be commemorated on postage stamps and fridge magnets. The decipherment was only possible, much as with Egyptian hieroglyphs, with the help of parallel inscriptions in more than one language. Just as the Greek translation on the Rosetta Stone allowed pioneer Egyptologists to unlock the version in Egyptian hieroglyphs, so an Old Persian cuneiform inscription at Bisutun in Iran enabled contemporary Babylonian cuneiform of around 500 BC, to be, gradually, understood. This was because the old Persian text was accompanied by a translation into Babylonian. In both cases the spelling of royal names, Cleopatra and Ptolemy in Egyptian, Dariawush (Darius) in Babylonian, provided the first glimmerings of understanding of how these ancient, essentially syllabic sign systems worked.

Without some bilingual prompt of this kind, cuneiform would probably have remained impenetrable for ever. The first identified cuneiform signs, da-, ri- and so forth, coupled with the suspicion that Babylonian might be a Semitic tongue, meant that decipherment found itself on the right track from early on, and progress followed comparatively rapidly. Crucial brainboxes here were Georg Grotefend (1775–1853) and Henry Creswicke Rawlinson (1864–1925) for the Old Persian version, and, most importantly, the Irish clergyman Edward Hincks (1792–1866), an unsung genius if ever there was one, who, marvellously, took up cuneiform studies in the hope that they would aid him in his serious work on Egyptian hieroglyphs. Hincks was the first person in the modern world to understand the nature and complexities of Babylonian cuneiform. One persistent cause of confusion was how to tell the difference between Sumerian and Akkadian since they were both written in one and the same script. Some scholars still believed right into the twentieth century that Sumerian was not a real language at all, but a sort of code made up by the scribes. There were cuneiform codes, as a matter of fact, but Sumerian was not one of them. Today we have full sign lists, advanced grammars and weighty dictionaries to help us read ancient Babylonian, and similar resources for Sumerian. With these extraordinary advantages created by generations of heroic scholars it is now possible to read the Ark Tablet and quite comfortably translate it into English.

The venerable culture of this antique land is something extraordinary, the contributions of which to the modern world often go unnoticed. Every thinking child, for example, has at one time or another asked why minutes and hours are divided into sixtieths of all things instead of sensible tens, and why, worse yet, circles are divided into three hundred and sixtieths. The reason is the Mesopotamian preference for sexagesimal mathematics, which developed with the dawn of writing and persisted unthreatened by decimal counting. Counting in sixties was transmitted from Mesopotamians to us by serious-minded Greek mathematicians, who encountered Babylon and its records, thoroughly sexagesimal, still alive at the end of the first millennium BC, spotted their potential and promptly recycled them; the consequence is celebrated on everybody’s wrist today. Mesopotamia’s place on the archaeologist’s roll of honour will always be high: out of the ground have come the wheel and pottery, cities and palaces, bronze and gold, art and sculpture. But writing changed everything.

From the earliest times, well before 3000 BC, nomads came to settle in Mesopotamia, attracted by abundance and blending amicably into the resident populations. Some of the newcomers spoke an early form of Akkadian, which, in its Assyrian and Babylonian forms, was to co-exist with Sumerian for more than a millennium until the latter subsided into a purely ‘bookish’ role, much like Latin in the Middle Ages. Akkadian survived as Mesopotamia’s main spoken language altogether for a good three thousand years, evolving as any language must over such a long period, until it was eventually knocked out for good by another Semitic tongue, Aramaic, at the end of the first millennium BC. By the second century AD, as the Pax Romana, or ‘Roman peace,’ prevailed and Hadrian was planning his wall, the last readers and writers of cuneiform were dying in Mesopotamia, and their distinguished and hallowed script became finally extinct until it was so brilliantly deciphered in the nineteenth century AD.

Third-millennium Sumerian culture had seen the rise of powerful city-states that lived in uneasy collaboration; it took the political abilities of Sargon I, king of Akkad, in about 2300 BC to develop (to the delight of later historians) the first empire in history, stretching far beyond Mesopotamia proper into modern-day Iran, Asia Minor and Syria. His capital, Akkad, probably somewhere near the city of Babylon, gave rise to our modern term for his language and culture, Akkadian.

The break-up of Sargon’s empire saw a Sumerian renaissance and the rise to prominence of the city of Ur, famous especially as the birthplace of Abraham. Here a succession of powerful kings like Naram-Sin, or Shulgi supported empires and trading of their own in about 2000 BC without ignoring the claims of music, literature and art, and even boasting of their accomplishments as literati, musicians and men of culture.

Incursions of Semitic Amorite speakers from the west of Mesopotamia proper ushered in a succession of new dynasties, so power came to relocate from the city of Isin to nearby Larsa and ultimately to Babylon, where Hammurabi set up his iconic law-code in the eighteenth century BC, quoted in the previous chapter. The northern ‘Iraqi’ territory meanwhile saw Assyria establish her own far-flung empire. Assyrian armies, undeterred by hardship, hunted new terrain and tribute, with a string of famous kings like Sargon II, or Byron’s Sennacherib – the wolf on the fold – and Great Librarian Ashurbanipal. Babylon, rid of invader Kassites, could ultimately collaborate with the Medes in the East to destroy Assyria for ever; the fateful destruction of Nineveh in 612 BC changed the world for ever and paved the way for the Neo-Babylonian Empire under Nabopolassar and Nebuchadnezzar the Magnificent, the latter of whom plays an important role in this book. Nabonidus, the last native Mesopotamian king, lost his throne to Cyrus the Achaemenid in 539, and then came Alexander, the Seleucid kings and, ultimately, the end of the ancient Mesopotamian world.

*

Once the script had achieved maturity and grown beyond book-keeping, writing was applied with increasing liberality and inventiveness. Key dictionary texts from the early third millennium BC were soon followed by the first Sumerian narrative literature and royal inscriptions; by the closing decades of that millennium private letters accompany the unrelenting flow of administrative record-keeping. Semitic Akkadian texts remain rare before 2000 BC, but before long comes a richer literature in both Sumerian and Akkadian, with the first magical and medical texts and a wide sweep of omen or fortune-telling documents, and an increasing waterfall of economic and official documents, themselves now put in context by codified sets of laws.

We can be sure that from very remote times favourite narratives about gods and men were transmitted orally, but after 2000 BC such works were increasingly committed to writing. As the old Sumerian tongue became hazy or obscure, many classical texts came to be translated word for word into Akkadian with the help of the lexical texts. Bilingual or two-language versions of hymns, spells and stories led the most gifted ancient scholars in the peace of their academies to undertake sophisticated grammatical studies in which the linguistically unrelated Sumerian and Akkadian were analytically compared. Some of the most revealing texts are round, currant-bun school exercises from Old Babylonian times, which give an open window on the curriculum that was designed to instil cuneiform literacy and ability in practical mathematics, offering us at the same time a glimpse of uncommitted pupils and the liberal use of the stick.

Archives of merchant or banking families are often scattered far and wide due to ‘informal’ excavation in the nineteenth century, but working in collaboration, scholars today can reconstruct awe-inspiring details of marriages, births, deaths and the price of goods in the market. Those record-keepers would be utterly astonished if they knew what we get up to today. In the first millennium we even have, most wonderful of all, cuneiform libraries, where orderly housekeeping by real librarians meant that tablets were stored on end in alcoves according to the system. As both Babylonian language and script began to wind down in some quarters at the end of the first millennium BC, disciplines such as astrology and astronomy generated increasingly complex literature in traditional wedge-shaped form.

Cuneiform tablets that are so precious to us now were usually just dumped in antiquity or recycled as building fill; only seldom are they discovered nicely sealed in a datable destruction level for the benefit of the archaeologist. Tablets in general become more plentiful with the passage of time, but Assyriological assessments of distribution or rarity are seldom significant; data usually reflect nothing more than the accident of survival.

The most famous cuneiform library belonged to Assurbanipal (668–627 BC), the last great king of Assyria, who had a bookish mind. The royal librarian was always on the hunt for old and new tablets for his state-of-the-art Royal Library at Nineveh; his plan was to collect the entire inherited resources. His holdings, now the pride and joy of the British Museum tablet collection, were one of the real wonders of antiquity (far surpassing gardens or lighthouses), and we can still read Assurbanipal’s written orders to certain ‘literary’ agents who were despatched down south to Babylonia to borrow, purloin or simply commandeer anything interesting that was not already included on the royal shelves:

Order of the king to Shadunu: I am well – let your heart be at ease!

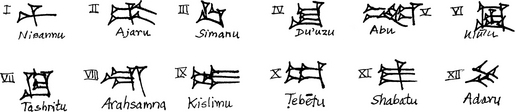

The day you read (this) my tablet, get hold of Shumaya son of Shuma-ukin, Bel-etir, his brother, Aplaya, son of Arkat-ili and the scholars from Borsippa whom you know and collect whatever tablets are in their houses, and whatever tablets as are stored in the temple Ezida; tablets (including): those for amulets for the king; those for the purifying rivers for Nisannu [month I]; the amulet for the rivers for the month Tashritu [month VII]; for the House-of-Water-Sprinkling (ritual); the amulet concerning the rivers of the Sun’s decisions; four amulets for the head of the king’s bed and the feet of the king’s bed; the Cedar Weapon for the head of the king’s bed; the incantation ‘May Ea and Asalluhi combine their collected wisdom’; the series ‘Battle’, whatever there might be, together with their extra, single-column tablets; for ‘No arrow should come near a man in battle’; ‘Walking in Open Country’, ‘Entering the Palace’, the instructions for ‘Hand-Lifting’; the inscriptions for stones and … which are good for the kingship; ‘Purification of a Village’; ‘Giddiness’, ‘Out of Concern’, and whatever is needed for the Palace, whatever there is, and rare tablets that are known to you do not exist in Assyria. Search them out and bring them to me! I have just written to the temple-steward and the governor; in the houses where you set your hand no one can withhold a tablet from you! And, should you find any tablet or ritual instruction that I have not written to you about that is good for the Palace, take that as well and send it to me.

The king regarded Babylonian handwriting with disfavour, and so a roomful of trained calligraphers at the capital worked around the clock to produce perfect Assyrian copies of the incoming acquisitions for him. In time the Nineveh libraries grew to contain the richest tablet resources ever put together under one Mesopotamian roof, anticipating, in some measure, the ideas behind the library at Alexandria.

What it would be to spend a week in Assurbanipal’s library! The prime fantasy element for the cuneiform reader is that all the individual documents and multi-tablet compositions would have been complete on the shelves; Gilgamesh I–XII all in a row: none of the library tablets would have been tolerated in broken condition, and, if something untoward happened, they would be recopied. Everything was available in full. This is truly the stuff of dreams, for it is seldom indeed that a perfect cuneiform tablet comes to light, and Assyriologists are conditioned to live with broken fragments and damaged signs, never ‘knowing the end of the story’. In Assurbanipal’s day scholars who wanted to talk over the interpretation of a thorny phrase occurring in a letter to the king about some ominous occurrence could pull down from the shelves (1) the standard version – complete; (2) a variant edition from Babylon or Uruk in the south – complete; (3) a highly ‘unorthodox’ or provincial version from some obscure place that still ought to be consulted – complete; and (4) any number of explanatory commentaries, where learned diviners had already recorded their own bright ideas which might bring insight – complete. Perhaps they might also have to hand some really venerable tablet, valued even if fragmentary and accorded special care, although the administrators would always be on the lookout for a better copy. Today we can muster bits of all this range of library writings, and it takes a huge leap of imagination to envisage a situation where the only problem for a tablet reader might be to understand the sense of the signs or the meaning of the words. The king’s effort at completion in assembling top-quality clay manuscripts meant that the first resources seen by Western decipherers in the middle of the nineteenth century were both the fullest and most easily legible of any that could possibly have been dug up for them.

Nineveh’s destruction in 612 BC at the hands of the Medes and Babylonians saw the palatial buildings sacked and burnt, but fire to a clay librarian was not the disaster that it was to Eratosthenes, the keeper of the scrolls. When Assurbanipal’s tablets were discovered in the nineteenth century, as deliciously described by Henry Layard, the thousands of broken pieces were mostly in fine condition, fired to crisp terracotta, awaiting decipherment and ‘re-joining’ by generations of patient Assyriologists over the centuries to come. Fortunately many of Assurbanipal’s literary treasures existed in several duplicating copies, so that today the wording can sometimes be recovered in full even when none of the source tablets is itself complete. It was this library that contained the Assyrian pieces of Atrahasīs and the Epic of Gilgamesh, which George Smith was the first to identify and translate.

*

Given what lies in the world’s museums and collections it will be a long time before there is a shortage of cuneiform material to work on and there is always a shortage of workers. In the nineteenth century, after decipherment had been achieved, standards for scholarship were set very high. The true giants – usually hot-house trained in Germany – knew their Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Coptic, Ethiopic, Syriac and Aramaic before they even looked at Babylonian. On top of that they stood tall in other ways and it is astonishing how fast-acquired and deep was their understanding. When I first started work at Chicago in 1976 Erica Reiner, then editor of the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, mentioned one day that her predecessors Benno Landsberger and Leo Oppenheim (later examples of these giants) had both read every cuneiform text published since it all began in 1850 (and, what is more, remembered every line). Today, when cuneiform books, articles and texts are published uninterruptedly, this feat would be beyond anyone’s abilities. One consequence of this is that modern scholars tend to limit themselves to one or other language and one or other period with increasingly narrowing perspectives. In Lambert’s classroom this nail-buffing, I-am-a-specialist idea that we sometimes encountered in visiting scholars was heavily frowned upon and later subjected to derision, for a real cuneiformist was expected to read anything and everything in either language, and quickly too. This model stood me in good stead when I got to the British Museum, for that is what has to be done.

And what is it all? I think it is beneficial to see our roomfuls of cuneiform documents at large as falling into five loose categories: official (state, king, government, law), private (contracts, inheritance, sales, letters), literary (myths, epics, stories, hymns, prayers), reference (sign lists, dictionaries and mathematical tables) and intellectual (magic, medicine, omens, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, grammar and exegesis).

Each single tablet, to a greater or lesser extent, contributes information. Some, like the Ark Tablet which is central to this book, offer something astonishing with almost every line of text, others find their niche as part of a broad study, or contribute no more than a couple of signs that can, once in a while, settle a textual debate that has continued for a century. Reading a tablet satisfactorily is like squeezing a bath sponge; the more determined the grip the greater the yield. It is always exciting to get the sense of a cuneiform inscription from so long ago, even when you do it every day; each surviving message is, frankly, miraculous. To paraphrase Dr Johnson, he who is tired of tablets is tired of life.

I have been happily reading cuneiform tablets every day now for about forty-five years. (As Arlo Guthrie would say: I’m not proud. Or tired. I could read them for another forty-five years.) During such prolonged exposure an impression gradually but unavoidably begins to take shape about the long-dead individuals who actually wrote these documents. We can handle their handiwork and read their words and ideas, but, I find myself asking, can one grasp at identity within these crowds of ghostly people for whom, as the poet put it, ‘dust was their sustenance and clay their food?’ The question finally crystallises into a single, and I think important, problem: were ancient Mesopotamians like us or not?

Scholars and historians like to stress the remoteness of ancient culture, and there is an unspoken consensus that the greater the distance from us in time the scanter the traces of recognisable kinship; my elementary school question is usually avoided altogether. As a result of this outlook the past comes to confer a sort of ‘cardboardisation’ on our predecessors, whose rigidity increases exponentially in jumps the further back you go in time. As a result the Victorians would seem to have lived exclusively in a flurry about sexual intercourse; the Romans worried all day about toilets and under-floor heating, and the Egyptians walked about in profile with their hands in front of them pondering funerary arrangements, the ultimate men of cardboard. And before all these were the cavemen, grunting or painting, reminiscing wistfully about life back up in the trees. As a result of this tacit process Antiquity, and to some extent all pre-modern time, is led to populate itself with shallow and spineless puppets, denuded of complexity or corruption and all the other characteristics that we take for granted in our fellow man, which we comfortably describe as ‘human’. It is easiest and perhaps also comforting to believe that we, now, are the real human beings, and those who came before us were less advanced, less evolved and very probably less intelligent; they were certainly not individuals whom we would recognise, in different garb, as typical passengers on the bus home.

After decades among the tablets I have become very doubtful that this wall of detachment from individuals who come out of the past is appropriate. We are, for one thing, talking only of the last five thousand years, a mere dollop in Time terms, in which snail processes like evolution or biological development have no measurable part. Nebuchadnezzar II ruled at Babylon from 605–562 BC, ascending to the throne 2,618 years before this book was brought into being.

*

How can one actually visualise that interval of time clearly in order to bring the ancient king closer? If thirty-five individuals in a line live for seventy-five years each in historical sequence, the result is a straight run of 2,625 years. Thus a chain like a cinema queue of no more than thirty-five cradle- to grave lives divides us from people who lived and breathed when Nebuchadnezzar was king. This is not, after all, unimaginable remoteness in time past. And we can hardly flatter ourselves that ‘we’ are any more intelligent than, say, Babylonians who practised mathematical astronomy for a living. There were Mesopotamian geniuses and Mesopotamian numbskulls walking about at the same time.

This issue, whether ancient writers can be accessible and familiar as human beings, affects very seriously how we interpret their writings. I am reluctant to settle for the faraway and unattainable nature of the ancient Mesopotamian mind, the remoteness of which has often been stressed, particularly with regard to religion. In my view humankind shares a common form of starting ‘software’ which is merely given a veneer by local characteristics and traditions, and I argue that this applies to the ancient populations of the Middle East exactly as it does to the world today. The environment in which an individual exists will contribute formative, possibly dominating pressures; the more enclosed the community the more conformist the individual will be, but, evaluated from a broad perspective, such differences are largely cosmetic, social and in some sense superficial. Take Pride and Prejudice. In their outer wrapping, the characters within it do look a bit odd from a very contemporary perspective, with their social mannerisms, codes of behaviour and religious practice, but their motives, behaviour and humanity are in every way familiar. So it must be as one vaults backwards in time, and so it is with Shakespeare and Chaucer, and the Vindolanda tablets in demotic Latin, and Aristophanes, and there we are, BC already. One species in myriad disguises. In my estimation the old cuneiform writers have to be inspected with the right end of the telescope, the one that brings them closer.

If tablet writings are to provide an answer to the question of how accessible Mespotamians were, it must be granted, of course, that they will always give incomplete information. Far from everyone had a voice. And then a high proportion of our cuneiform documents are official, formulaic and hidebound by tradition, rarely innovative and often manipulative. Assyrian military campaigns, for example, are portrayed on stately prisms of clay as a matter of unimpeded triumph, with huge booty and minimal loss of Assyrian life; such accounts require the same necessary reading between the lines that historians must apply to modern journalism.

The most informative documents will be those of the everyday world, which ought to be impulsive, informal and unselfconscious in comparison. There are two cuneiform categories among these which are undoubtedly the most helpful from this point of view: letters and proverbs.

Huge numbers of private letters survive, for they come in a particularly durable, fit-in-the-hand size and are not as readily broken as larger tablets. These letters, often exchanged by merchants who were irritated with one another about slow delivery or overdue payment, sometimes allow us to eavesdrop. Flattery – (I am so worried about you!) alternates with irony – (Are you not my brother?) – spiced with wheedling or threats, and the timeless claim that the letter is in the post occurs endlessly – I have already sent you my tablet!

Letters can give us a remarkable picture of people going about their lives, preoccupied with ‘money’ and mortgages, worried about business, sickness or the lack of a son. From our over-the-shoulder vantage point can come a moment of closeness to an individual, or a sense of fellowship with the harassed – or crafty – person ‘at the other end’.

How did cuneiform letters function? The operation was cumbersome and of a slower-paced world. Letters despatched to colleague or foe usually went to a different town as otherwise it would have been simpler to go and talk. The message had to be dictated to a trained scribe, carried from A to B, and read aloud by the recipient’s own scribe when it finally arrived. This is explicit from the words that open almost every example: ‘To So-and-so speak! Thus says So-and-so …’ and in the actual Akkadian word for letter, unedukku, loaned from the Sumerian u-ne-dug, ‘say to him!’ Since fluent letter dictation is beyond most people today I think we must imagine a merchant starting off, ‘Tell that cheat …’; no, wait a minute; ‘May the Sun God bless you etc. – ha! curse more like … o.k. o.k.; here we go: When I saw your tablet …’ The scribe, experienced and patient on a stool, would jot down the main points as they emerged and then produce a finished letter on a proper-looking tablet. Outside on a wall it would dry in the warm air, and then go into a runner’s ‘post-bag’ for delivery.

The sender knows the background: usually we don’t. He gets his answer: again, usually we don’t.

Those who read other people’s correspondence must harvest everything possible: spelling, word forms, grammar and idiom, sign use and handwriting. Squeezing the sponge involves more than the extraction of clear facts; also crucial is inferring, with varying degrees of probability, a good deal more: What led to the letter; what light might it throw on trade, social conditions, crime and immorality, not to mention the person of the writer himself? Such inferences derive from knowledge of contemporary documents seasoned with common sense.

There is an additional useful factor, the Sherlock Holmes principle that, we are told, he wrote up in a magazine called The Book of Life:

‘From a drop of water’, said the writer, ‘a logician could infer the possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of one or the other.’

A. Conan Doyle, A Study in Scarlet

In my experience, this Niagara principle is of considerable value to the practising Assyriologist. A good case of this is Babylonian surgery. References to surgical practice of any kind are rare in the medical texts. Cataracts were dealt with using a knife and there is a text where infection is released from the chest cavity by some kind of inter-rib incision. But, in comparison with Egyptian medicine across the sands where the Edwin Smith surgical papyrus gives astonishing procedural treatments for injuries and wounds, Babylonian doctors do not measure up. This seems curious. The mighty Assyrian army was constantly in the field. A deterrent clause in an Assyrian political treaty focuses on the reality of battle wounds, with a glimpse of emergency treatment, possibly even self-applied: If your enemy stabs you, let there be a lack of honey, oil, ginger or cedar resin to apply to your wounds!

Over the centuries there must have been a very considerable inherited, practical, medical field knowledge: staunching of blood loss, extracting arrows, stitching wounds, and emergency amputations with hot pitch; also important was judging whether a wounded soldier was even worth the saving; all this stands to reason. None of our known therapeutic texts sheds light on this, however. So we have to assume either that all medical lore in the army was transmitted, hands-on from expert to tyro, without recourse to written form, or that no such text happens to have come to light. In my understanding it is the second explanation which is true.

Going back to the Niagara principle, an important scribe in the Assyrian capital at Assur once drew up a catalogue of medical compositions available in a library there. He included a section with the following tantalisingly incomplete titles, quoted by their first line:

If a man, whether by sword or slingstone …

If a man … in front of a ship.

These lost tablets must have dealt not with diseases or demons but, compellingly, with injuries: military, industrial or caused by a goring ox. They give us a glimpse of what was once written down about Mesopotamian wounds, just as happened in ancient Egypt. One day I shall find those tablets.

The richest ‘fellow man’ vein of writing to pursue is cuneiform proverbs and wisdom literature, some of which go back, surprisingly, into the third millennium BC, and which are a staple of the scribal schools. The Sumerians made use of a device that tends to make right-thinking youths wriggle with impatience:

In those days, in those remote days,

In those nights, in those faraway nights,

In those years, in those far remote years,

In those days, the intelligent one, the one of elaborate words, the wise one, who lived in the country,

The Man from Shuruppak, the intelligent one, the one of elaborate words, the wise one, who lived in the country,

The Man from Shuruppak, gave instruction to his son –

The Man from Shuruppak, the son of Ubartutu – gave instructions to his son Ziusudra:

“My son, let me give instructions; let my instructions be taken!

Ziusudra, let me speak a word to you; let attention be paid to them!

Don’t neglect my instructions!

Don’t transgress the words I speak!

The instructions of an old man are precious; you should comply with them …”

The Man from Shuruppak was ruler of the last city before the Flood, and he is addressing his son Ziusudra, the Sumerian equivalent of Noah in the Bible (as we will see later!), who built the life-saving ark and obtained eternal life for himself. The instructions that follow are nothing to do with arks or ship-buildings, however, but are precepts from an agricultural culture that promote a kind of ethics that Bendt Alster, the translator, called ‘ “modest egoism” that is, don’t do anything to others that may provoke them to retaliate against you’. This was a much-valued composition; the first texts appeared around the middle of the third millennium BC, and it was still being read in first-millennium Assyria and Babylonia, with the benefit of an Akkadian translation which is equally useful for us.

Proverbs, and the wisdom literature that derives from them, thus come in both Sumerian and Akkadian, and pithy, sardonic and cynical mots seem to flow naturally in Sumerian. ‘Don’t laugh with a girl if she is married: slander is powerful’ is a rueful example. The word for ‘virgin’, kiskilla, literally means ‘pure place’, and girls at the beginning of history were most definitely supposed to be a virgin on marriage. One Babylonian roué, arraigned before a judge in about 1800 BC, testified, I swear that I did not have intercourse with her, that my penis did not enter her vagina; not, one reflects, the last time someone has got off on that technicality. Mesopotamians were always fearful of slander; it was one of their things, and they called it ‘evil finger-pointing in the street’, but victims could always toss painted clay tongues inscribed with power words into the river as a remedy. King Esarhaddon himself once reflected in a seventh-century letter from Nineveh, ‘The oral proverb says: “In court the word of a sinful woman prevails over her husband’s” ’, while a classic of Babylonian wisdom literature advised, ‘Do not love, sir, do not love. Woman is a pitfall – a pitfall, a hole, a ditch. Woman is a sharp iron dagger that cuts a man’s throat.’ One can pass a pleasant hour reflecting on such statements.

Unfortunately, not a great deal is known about the scribes themselves. At all periods they were almost invariably male. It is likely that there were scribal families, and that access to formal schooling was limited to such circles. To become a scribe in Mesopotamia required exhaustive training, as we can see from lots of surviving old clay schoolbooks, especially from the Old and Neo-Babylonian periods, about 1700 BC and 500 BC. There is even an entertaining cycle of stories in Sumerian about what happened in the classroom, as much fun to read now as they must have been originally. Making a proper tablet (which is not so simple!) was followed by a strict diet of wedges, signs, proper names, dictionary texts, literature, maths, spelling and model contracts. This training gave a scribal family boy his basic grounding. At this stage he could technically spell and write whatever he wanted, and perhaps the majority would find work as commercial scribes, sitting at the city gate and taking on all comers who needed a bit of writing done when they were selling some land or marrying off a daughter. ‘Graduate’ students, in turn, would specialise in their chosen field; an apprentice architect would study advanced maths, weight systems (also not so simple!) and how to make things stay up once they were put up, while novice diviners would learn to expound each corner and wrinkle of a diseased sheep’s liver. Very often, it seems, such ‘professionals’ were sworn to secrecy in the process.

Small notations bring the Mesopotamian ṭupšarru, or ‘tablet writer’, even closer. Library and scientific texts sometimes have a line along the top edge in easy-to-miss, minute writing: ‘At the word of My Lord and My Lady may this go well!’ Such an utterance – for it was probably muttered more than once under the breath as well as inscribed – is very understandable, for cuneiform mistakes had consequences: clay is an unforgiving medium and invisible correction almost impossible. Many a time a scribe, checking over his work, must have sighed wearily and started another tablet; erasures and errors that come through are, generally speaking, conspicuously uncommon. Sometimes, however, a whole line gets omitted, the scribe making a diminutive ‘x’ mark to indicate the point of omission and writing out the lost signs down the side from a point with another ‘x’. To avoid this problem, long or elaborate documents often marked every tenth line at the left side with a small ‘ten’ sign, confirmed by a line total at the end, since it was as easy for a Babylonian eye to jump a line as it is for a modern copy-typist’s and checking aids were very helpful. Sometimes a worried scribe records that he has not seen all the text, or makes a note in similar tiny cuneiform signs to show that the tablet he was copying was broken. There are two degrees: hepi (it-was-broken), and hepi eššu (a new it-was-broken). In principle the system worked like this. The scribe Aqra-lumur, seated in some institution, is copying out the text of an important tablet. There is a damaged passage that he cannot read with certainty, so he writes hepi (it-was-broken) where signs or wedges are abraded. The scribe who makes a copy of Aqra-lumur’s tablet takes care to reproduce all cases where his predecessor wrote hepi. Thus is set in train a process of transmission whereby any number of scribes preserve as accurately as possible the situation first encountered by Aqra-lumur. Notations like this are revealing, for hepi (it-was-broken) is found in places where even we can tell what is missing, highlighting that the scribe’s task was to transmit old texts found precisely, without imposing himself or his ideas even when the restoration was self-evident. As this line of transmission proceeds it comes about that a subsequent tablet in the chain gets chipped or broken itself. This damage is, so-to-speak, new, and will be indicated by hepi eššu (a new it-was-broken). Literary texts often concluded with a colophon that recorded the source of the text and the scribe’s name. With very venerable documents these successive colophons were all copied out, so a given tablet might have three of them, in chronological order.

Three generations of scribes record their efforts to transmit an ancient and extremely damaged cuneiform tablet, recording their own names and family names on the reverse.

This very sketchy scribal picture – for this is a big topic with sprawling evidence – leads to a separate question:

What was the level of literacy in society at large in, say, the first millennium BC?

Nobody in ancient Mesopotamia ever stood on a street corner soap-box to advocate literacy for all, and, up until recently, Assyriologists have mostly taken it for granted that the ability to read and write was highly restricted in Mesopotamian society. (There is an attractive paradox in the construct of an age-old, highly literary culture in which hardly anyone at any particular time was in fact literate.) I have a suspicion that this evaluation derives ultimately from what King Assurbanipal had to say at home in seventh-century Nineveh. A special note at the end of many of his library tablets recorded boastfully that – unlike the kings who preceded him – he could even read inscriptions from before the Flood:

Marduk, the sage of the gods, gave me wide understanding and broad perceptions as a gift. Nabu, the scribe of the universe, bestowed on me the acquisition of all his wisdom as a present. Ninurta and Nergal gave me physical fitness, manhood and unparalleled strength. I learnt the lore of the wise sage Adapa, the hidden secret, the whole of the scribal craft. I can discern celestial and terrestrial portents and deliberate in the assembly of the experts. I am able to discuss the series ‘If the Liver is the Mirror Image of the Sky’ with capable scholars. I can solve convoluted reciprocals and calculations that do not come out evenly. I have read cunningly written text in Sumerian, dark Akkadian, the interpretation of which is difficult. I have examined stone inscriptions from before the flood, which are sealed, stopped up, mixed up.

We know, in fact, that Assurbanipal was literate, for nostalgically he kept some of his own school texts, but is it justified to conclude from this statement that Assyrian kings otherwise were completely illiterate? For me it is impossible to credit that mighty Sennacherib, accompanying foreign potentates through the halls of his Nineveh Palace where the sculptures were inscribed with his name and achievements, would have been unable to explain a cluster of cuneiform signs on demand. Surely any king worth the name, pulled this way and that by advisors, technicians, diviners and what have you, would need, if only for self-protection, some cuneiform know-how? An educated monarch, moreover, would not do his own writing; there were staff to do all that. But there has been a direct overspill from Assurbanipal’s literary boast: And if kings were usually illiterate, how much more so the great unwashed?

This limited-literacy idea is probably compounded by the nature of the cuneiform discipline itself. Assyriologists today have to master absolute shelves of words, grammar and signs. Those who survive indoctrination often feel that the ability to read cuneiform can never be taken for granted in anyone else, including the ancients. It is easy, however, to forget that in ancient Mesopotamia everyone already knew (a) the words and (b) the grammar of their own language, even if they were unaware that they knew such things. This left only the cuneiform signs to be mastered. The truth, as has been seen in more recent books, must be that many people knew how to read to some level, or, rather, to the level that they needed. Merchants were in charge of their own book-keeping; some son or nephew had to record all the contracts and loans, and commerce is a great motivator to book learning. It is inconceivable to me that all cuneiform writing was constrained in a professional, those-who-need-to-know box. The real situation to be envisaged is that within a large city there must have been very different levels of literacy. Very few individuals can ever have known all the rarest signs in the sign lists together with all their possible readings, but the number of signs needed to write a contract or a letter was, in comparison, very restricted; some 112 syllable signs and 57 ideograms to write Old Babylonian documents, while Old Assyrian merchants (or their wives) needed even less. Similarly modest was the range of signs needed to inscribe the palace walls of the Assyrians with triumphant accounts of conquest. A parallel might derive from facility in typing in the 1960s. Anyone could type with two fingers but few such people would have called themselves a typist; certificated professionals at the other end of the spectrum who could do dazzling hundreds of words a minute most proudly would, while in between there was a wide range of ability. So it might well have been with sign recognition, many people having a ‘little bit’ of writing. Probably lots of people knew signs that could spell their own name, as well as those for god, king and Babylon; these were, after all, used everywhere. Letter writers and contract drafters knew what they needed to know, professional men a good deal more, and so forth.

Mesopotamian gods were everywhere, in sheer number beyond the mastery of all but the most learned of theologians, and man interacted with them, felt confident of their mercy or was needlessly punished by them throughout life. Such a profusion of gods drove the theologians to sort them out; god lists became a major strand of lexical endeavour, and there was a would-be tidiness about it all; small gods were identified or amalgamated with similar ones, or given domestic responsibilities within the household of their seniors.

Literature that touches the divine is abundant: hymns, prayers and litanies, rituals and other temple documents, as well as lists of gods or their sacrificial dues. Many of these, from our point of view, concern religious matters, although there was no ancient Sumerian or Babylonian word for ‘religion’ in today’s sense, and man’s relationship with the gods affected most aspects of his daily life.

Scholars often find themselves explaining how hard it is to write religious history from cuneiform sources. One reason is the great length of time that is involved, some three thousand years of inscriptions; another is the imbalance in what survives. For some periods there is rather too much evidence, such as thousands of detailed day-to-day Sumerian temple records; for others there is hardly a thing, or manuscripts might be broken, or obscure. Generally speaking, too, we know far more about ‘state’ or ‘official’ religion at all periods than about the private belief of individuals. Evidence about religion comes from official monuments and the pious statements of kings, from temple records of ritual and cult, from the incantations and prayers of healers and the esoteric writings of diviners and astrologers. The background to all this is supplied by myths and epics which show the gods in action. The religious calendar wound its way through the year with a network of traditional offerings, recitations and pious activity. When everything was in order and the powerful gods were content, they were to be found in residence in their temples, housed in the cult statues to which the priests attended. Divine anger or displeasure could cause a god such as Marduk to depart from his ‘house’, the consequences of which were breakdown and disaster. The theft of a cult-statue by an enemy, therefore, was cause for protracted mourning: absence of the statue meant the absence of the god himself. While the congregation of deities was too numerous and often too obscure to have been familiar to any but the most learned divines, everyone had heard of the main gods, and private individuals could feel that the particular god or goddess to whom they had been consecrated at birth looked out for them and was ‘there in the background’, to see to protection during life. There was, undeniably, something of the business contract underlying this arrangement, which was naturally found to be far from fail-safe. A good individual who fulfilled his obligations should feel confident that he would not fall sick at the hand of demons any more than his business would fail or his flocks fail to reproduce. Poetic incantation literature in the What-have-I-done-now? mould suggests a sense of betrayal in suffering, although it was conceded that man could transgress a taboo unwittingly and still be punished for it. Human sorcery was a parallel source of danger, and fear of that and dealing with it are common topics.

Some Mesopotamian gods and goddesses had held sway since the third millennium BC, and all had their level of status and characteristic ‘strong points’. The most elevated were attached to the main cities – Enlil to the city of Nippur, or Sin the Moon God to the city of Ur, Abraham’s birthplace – while small towns and villages likewise had their ‘own’ local god or goddess. Many native gods survived the transition from Sumerian to Semitic consciousness with no difficulty, sometimes blending one into another, as when the Sumerian Inanna, goddess of love and war, came to be ‘identified’ with Ishtar. This process, which allowed the two entities to exist on one level side by side, had the effect of moulding them, at least by the end of the second millennium BC, into what was really one multi-faceted deity, although both names remained in use. Descriptions of individual gods and epithets and achievements which were specific or exclusive to that individual are often hard to trace. The ancient gods and goddesses of Mesopotamia, like their counterparts elsewhere, were modelled on the human race: they were unpredictable, wilful, inscrutable, unreliable and often indulgent, and much of man’s attempts to communicate with them took account of such factors in prayer, ritual and behaviour.

In all this time, as is to be expected, the status of the important gods could change and evolve, often due to political circumstances. Marduk was only a little-known god when King Hammurabi first established Babylon as his capital and began his dynasty, more than a millennium before the time of Nebuchadnezzar II. This process was to propel Marduk, god of city and state, into ever-increasing prominence.

Kings professed themselves constantly under the umbrella of divine protection from the most powerful gods, but it is usually impossible to grasp the nature of their own private belief under the wording. It is improbable, too, that the majority of soldiers, merchants and farmers knew a great deal about the gods at large, for the mass of theological data known to us reflects a very minor and closed-in side of religious life in general. In villages one local god and his plump consort would likely feature to the exclusion of most others, but inner religious thoughts or reflections of individuals never made it onto clay. In the large cities things were, at least outwardly, different. Public processions and festivals brought people into closer contact with the gods in statue form or through the annual cycle of their sacred lives, even if the spiritual heart of such activity was carried out in camera. Shrines with images were to be found at city street corners. Large temples must have been refuges for people in need as well as in piety, and cheap clay figures of the type to infuriate the Hebrew prophets were available from vendors who set up stall nearby large temples.

*

Certain ‘hallmark’ aspects of ancient Mesopotamian life recorded in cuneiform writings do not feature so centrally in other ancient cultures of which we are informed. Let us look at two or three.

Among such hallmark elements known to us from writings, the quintessential Mesopotamian preoccupation is the restless urge to predict the future. A good percentage of intellectual thought over the best part of three millennia was lavished on the desire to penetrate the veil, fuelled by the conviction that human beings could, everything being equal, obtain the needed information from the gods through well-established procedures. This field of activity generated a vast literature of carefully assembled one-line omens on this pattern:

If A happened, B will happen.

Here the sought-for outcome B, known as the apodosis, is deemed to be the consequence of an observed phenomenon, the protasis A. One example exemplifies how a diviner operated in about 1750 BC while examining the surface of a freshly extracted liver from a healthy sheep for diagnostic marks:

Protasis: If there are three white pustules to the left of the gall bladder

Apodosis: the king will triumph over his enemy.

Divination of this sort by animal entrails, especially the liver, was in place at least by the early third millennium BC and persisted unswervingly thereafter. The Sumerian king Shulgi, writing in about 2050 BC, was well up in techniques and responsibilities, and leaves his court diviner standing:

I am a ritually pure diviner,

I am Nintu of the written list of omens!

For the proper performance of the lustrations of the office of high priest,

For singing the praises of the high priestess and (their) selection for (residence in) the gipar

For the choosing of the Lumah and Nindingir priests by holy extispicy,

For (decision) to attack the south or strike the north,

For opening the storage of (battle) standards,

For the washing of lances in the “water of battle”,

And for making wise decisions about rebel lands,

The (ominous) words of the gods are most precious, indeed!

After taking a propitious omen from a white lamb – an ominous animal –

At the place of questioning water and flour are libated;

I make ready the sheep with ritual words

And my diviner watches in amazement like a barbarian.

The ready sheep is placed in my hand, and I never confuse a favourable sign with an unfavourable one.

…

In the insides of a single sheep I, the king,

The diviner’s importance, his range of procedures and the extent of his written resources increased as the centuries unrolled; omens were still vital enough when Alexander was at the gates of Babylon for the priests to forecast his death if he entered the city, correctly as it turned out. Omens could be derived from spontaneous events, such as a gecko falling from the ceiling into one’s breakfast cereal, or solicited through deliberate procedure, such as releasing caged birds and watching the patterns they make in flight.

The favoured system, as in the quotation above, was examining the liver (hepatoscopy) or sometimes the other organs (extispicy) of a sacrificed sheep for diagnostic signs which had been left there for the informed expert by Shamash, the Sun God. The decision would be made from the observed phenomena, in strict order of priority according to the importance of the liver part.

Such predictive activities remained a royal prerogative throughout the second millennium BC, but with the arrival of the first millennium different types of divination came within the reach of private – although probably wealthy – individuals. Centuries of specialist celestial observations finally culminated under Greek influence, in personal, contemporary-sounding horoscopes.

The backdrop canvas for significant chance happenings was nothing less than the whole of heaven and earth. Little in daily life was immune from possible ominous significance, and with truly dramatic phenomena, such as malformed animal and human foetuses, a major stream of literature developed to document all the possibilities.

In the first millennium BC a professional Mesopotamian diviner could take omens by interviewing the client’s dead relatives (necromancy), analysing his spontaneous or provoked dreams (oneiromancy), observing the patterns from scattered flour (aleuromancy), incense-smoke (libanomancy) or oil on water (leconomancy), or by tossing stones (psephomancy) or knucklebones (astragalomancy) onto a prepared diagram; there were no doubt many other systems. By Alexander’s time the streets of Babylon were probably awash with people who could tell you for a handful of istaterranus (as they called the Greek stater coin) via a dozen cunning systems whether you would soon be rich or your wife would produce a son.

The historical origin of the entire Mesopotamian prognostic system has been debated and often considered obscure, but in fact is probably simple and straightforward: a peculiar event on one occasion, such as the birth of a sheep with two heads, coincided with, say, noticeable success in the field of battle. A nuclear collection of carefully noted primary phenomena led in time to the flourishing of a kind of science, according to which there were always trackable markers to events that unfolded on many levels, so that the unusual accompanied by the memorable came to assume the nature of structured dogma: a recurrence of the same phenomenon would imply the same consequences. The core of the principal omen series – whatever the type – must, I think, derive from empirical observation; real occurrences were recorded with their apparent consequences. The desire to cover all eventualities led to major textual extensions in all directions, because analysing spotting on a sheep’s gall bladder needed to cover number, colour and position so that a precise result could be forthcoming. In some cases the desire for complete coverage led to absurdity (a sheep with eleven heads) or even technical impossibility (a lunar eclipse at the wrong time of the month) and with all fortune-telling genres the unbridled multi-tablet outpourings of the first-millennium diviners would have astonished their second-millennium forebears.

In the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin is a uniquely informative, malformed, diviner’s dogfish in bronze.

The case of the ominous dogfish: a study in bronze.

The right flank shows two fins but the left only one, and it is inscribed with an omen derived from this deficiency and a date:

If a fish lacks a left fin (?) a foreign army will be destroyed.

The 12th year of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon, son of Nabopolassar, king of Babylon.

To the Mesopotamian mind all abnormalities were ominous. Examples from the natural world, especially with misshapen foetuses, animal and human, were taken seriously and probably there was an obligation to report them to the capital, although we might expect that most people buried birth monstrosities of all kinds without a word and pretended they had never happened. Here a dogfish lacking a fin must have been dredged up in a canal at Babylon. The specimen itself would not survive for long, and, rather than pack it in salt, a scale model was produced in clay, and the cuneiform inscription added. We cannot as yet associate a military success with Nebuchadnezzar’s twelfth year, but the pairing of abnormality and omen must date from that moment. The fish abnormality and the victory coincide, and the two are instructively bracketed together from then on. The whole was cast in bronze, producing an indestructible record of the abnormality and its event vis-à-vis prediction association. The bronze fish that resulted would be a wonderful teaching device for the Diviner’s College.

This item is proffered as a fine case of the Niagara principle, whereby a single episode can imply a more widespread occurrence, for while it is at present unique I would infer that modelling abnormalities in bronze for reference was a regular practice on the grounds that, probably, there was a roomful somewhere in the Assyrian or Babylonian capitals of all manner of frightfulness done into metal for apprentices, later greeted with horror and melted down at once by conquering outsiders.

Misfortune, sickness and disease were in the main attributed to demonic and supernatural forces, although human witches and malevolent practitioners were an additional threat. Incantations were available to combat most of these problems, either by staving them off or helping to exorcise them. Masters in such procedure called āshipus had the know-how to cope with everything from the overdue arrival of a baby to ensuring that a new tavern would turn a good profit. Their stock-in-trade of amulets, spells and rituals is known to us from a surprising number of magical tablets. Such healers worked side by side, and evidently in harmony, with a different group of specialists known as asûs, who were more expert in drugs, almost entirely plant-based, and therapeutic treatments.

Most of what we know about Babylonian medicine concerns what Tom Lehrer once lucidly referred to as the ‘diseases of the rich’. Almost all of our sources and other relevant medical information originate in major cities such as Ashur or Nineveh in the north of ancient Iraq, or Uruk and Babylon in the south, where healers treated members of the court circle, the high administration and powerful merchant families, as is reflected in the complexity of their ritual and the elaborate and no doubt costly requirements of their materia medica. The poor and unimportant, or those who lived in the countryside, would hardly ever encounter the highbrow stream of curative activity as we know it from written tablets, although itinerant doctors and local midwives undoubtedly brought comfort to many, and knew what to do if there was anything that could be done.

Medical praxis in town at its fullest relied on a blend of amulet or incantation with the administration of drugs. Again one is entitled to demand what curative understanding lay behind two thousand years of cuneiform healing documents. The same plants were consistently used for the same condition, and the careful re-copying and collecting of hard-won knowledge into large, many-columned library tablets where all information was arranged in a head-to-foot sequence demands the concession from us that Mesopotamian treatments were assuredly more beneficial than otherwise. As Guido Majno put it, most human ailments are self-healing anyway, but there was undoubtedly far more to Babylonian medicine than that. Mesopotamians fled from investigating inside the human body but they knew a good deal from the internal workings of sheep (and disembowelled soldiers) and they were expert observers of exterior manifestations. A good healer would recognise recurrent conditions and know what would in time right itself and what in his drug collection could help among all the astringents, balms, diuretics and emetics. Pharmacological plant knowledge was very extensive and carefully documented. The combination of āšipu and asû at the bedside of a worried chamberlain’s daughter must have been very effective, with swirling incense and muttered imprecations in the shadowy room, a pricey amulet to be pinned at the bed head, and foul-tasting preparations mixed from unspeakable things in vials that went down with reluctance and no doubt came up again soon after.

I think, having been immersed in these fascinating texts for decades, that the ancient Mesopotamian system can be summed up as simultaneously instinctive and observation-based, with a solid underpinning of long-endorsed pharmacological samples, while at the same time a good part of the whole was, unwittingly, placebic. Among it all there was good stuff to learn from them, for the Hippocratic Greeks were by no means above incorporating Babylonian ideas in their new-cast treatises.

As time went by old magical spells in the Sumerian language were particularly valued by Babylonian exorcists, even though the words themselves were often no longer fully intelligible. Garbled spellings show that sometimes incantations had been learned by rote and written out by ear. A few spells are neither Sumerian nor Akkadian but true mumbo jumbo, the more foreign-sounding the better, especially if they come from the East, over the mountains in ancient Iranian Elam. There is an unusual yellowish tablet in large script in the British Museum inscribed with mumbo jumbo lines that were particularly effective for banishing unwanted domestic ghosts:

zu-zu-la-ah nu-mi-la-ah hu-du-la-ah hu-šu-bu-la-ah

These sonorous and outlandish words ending in -lah ‘sound’ like Elamite, and they can be found inscribed on other tablets or carved on obsidian amulets, frequently enough to show that this spell was popular over a long period. Collecting the examples together shows that the first magical word zu-zu-la-ah occurs in varying forms: si-en-ti-la-ah, zi-ib-shi-la-ah, zi-in-zi-la-ah and zi-im-zi-ra-ah. Neither the exorcist nor his client would have had any idea what these four words meant, but it just so happens that today we have the advantage over them. Around 2000 BC, Sumerian administrators imported fierce mastiffs from Elam over the border where such dogs were bred, and their handlers, who were very probably the only people who could handle them, had to come too.

Monthly rations records preserve the name and title of one such Elamite dog-handler, zi-im-zi-la-aḫ, ‘dog warden’, provoking, it cannot be denied, a trenchant ‘Aha!’ For this single name reveals the independent, mundane source of what later became an item of powerful magic. Some old record of Elamite personnel must have been discovered a thousand years or more later during a building operation – for Mesopotamians, unlike certain archaeologists, were always finding old tablets – and eventually brought to someone who could read. The bizarre run of unintelligible names in neat old signs could only be an irresistible spell of great antiquity, and it is not hard to imagine how the tablet itself would have been prized and its message ultimately incorporated into regular exorcistic practice: Now this is a really old spell from faraway in the East … I am not going to pronounce these words aloud for we should only whisper them, but if we write them on a stone and you wear it, or hang it up over there, there will be no more visitations …

There is another odd thing about Mesopotamian magical amulets of stone. The inscriptions are often in truly atrocious handwriting, with cuneiform signs split in half or even divided over two lines, both heinous betrayals of scribal convention. Fortunately the worst specimens have been properly excavated on ancient sites, otherwise everyone would just say they were forgeries. Of course one could argue that these were not the work of scribes as such, but of illiterate craftsmen who engraved the scene on one side and blind copied the text from a master draft on the other. This explanation, however, will not wash. Magical inscriptions conventionally need to be free of error to be effective, and figural carvings on amulets are, in stark contrast to the written signs, often of such a high standard that they showcase the capabilities of craftsmen who could never have been satisfied with shoddy distortion of the signs. Hard stones were never cheap and even people who could not read at all would likely sense that such sloppy writing quality didn’t really justify the cost. At the same time, however, cuneiform spells on amulets can employ the rarest sign usages, reflecting highly learned input, and I think there must be another explanation to reconcile such incompatible evidence. Some incantations, like those against the she-demon Lamashtu who preyed on newborn babies, occur on many amulets, which list her seven cover names showing that everyone knew who she was. Perhaps the Babylonians had the idea that, if a common spell were legibly or beautifully written, Lamashtu, who had seen it all before, would recognise it from afar and be undeterred, as it was unfamiliar, whereas she might tell herself that a hard-to-identify incantation with distorted signs and obtuse spellings might be something dangerous, and move away to another house, just to be on the safe side. Identifying a familiar cuneiform inscription from twenty paces is perfectly possible: it is quite fun to do it when visitors bring in a stamped Nebuchadnezzar brick, which can be completely translated into English before it is halfway out of the wrapping.

It is an arguable proposition that human beings, whatever they may say, believe in ghosts. With the Babylonians there can be no doubt at all; their attitude to the restless dead is matter-of-fact and unselfconscious, and no one ever quizzically asked a neighbour waiting at a fruit stall if they ‘really believed’ in them. Ghosts were a common trouble, for anyone who died in dramatic circumstances or was not properly laid to rest or just felt abandoned by their descendants could come back and hang about disturbingly. At some periods dead family members were buried under house floors, and offerings had to be made to them via a special pipe. Seeing a ghost was troublesome; hearing them speak was much more worrying and the āšipu practitioner had a whole bag of tricks for sending ghosts back where they belonged once and for all. A typical ritual involved furnishing a little clay model of the ghost that was to be buried with a partner – male or female as was appropriate – and setting them up with all they needed for the return journey and peaceful retirement when they got there. These rituals, too, are elaborate; one exorcist determined to give clear instructions to a follower included a drawing of a ghost as a guide in making the model (see this page).

There was another, more worrying side to ghostly presence. Many diseases and illnesses in the medical omens were attributed to the ‘hand’ of a god, a goddess or other supernatural entities. Frequently mentioned among these is the Hand of a Ghost, which caused, among other afflictions, hearing problems (by slipping in via the ears) and mental disturbance. Unhappy ghosts whose legitimate needs were not attended to turned vengeful and became much more dangerous.

This huge mass of written cuneiform testimony, assorted religious texts, omens, medical and magical texts especially, is chock full of human ideas, for they represent the ways in which sentient individuals tried to make sense of their world and cope with it on all levels. The structure through which their data is presented is formulaic without being synthetic. Mesopotamian ideas, and therefore their sum of knowledge, come down to us in a specific kind of packaging. This packaging is above all practical, for its sole purpose was to present what was inherited from earlier times in usable, retrievable form. Knowledge derived from observation and its amplification was extensive and diverse but the fruit of the whole was never, or hardly ever, subjected to the type of analytical synthesis that a modern person, or an ancient Greek, would take for granted. No statement of principle or theoretical summary comes out of the cuneiform resources at our disposal.

This characteristic provokes the enquiry, difficult to satisfy, of the extent to which such intellectual processes took place at all. My own view is that the intelligent human mind is not always fettered by tradition, and I find it much harder to believe that no Babylonian ever asked himself philosophical or even non-conformist questions and that what we happen to have of the Babylonian mind on clay is all there was. It is far from valueless to consider how Babylonian ideas came about and functioned, and, to some extent, to visualise their practitioners.

There are two principal strands to knowledge storage. One is sign and word lists, which – as already indicated – I would categorise as reference works, the other a more intellectual branch which I would like to call If-thinking. Underlying both systems is a tacit principle of textual balance.

Lexical compositions are set up so that a word in the left-hand column is equated with another on the right. Lexical lists thus actually look like what they are, the juxtaposed entries neatly opposite one another. (An exception sometimes occurs in school texts when lazier pupils wrote out the whole of the left column before the right column; halfway down, the entries no longer match properly, with very unhelpful results.) Two juxtaposed words in a lexical text, most commonly Sumerian equated with Akkadian, do not necessarily share lexical identity to the point that word A means absolutely the same as B, but the system indicates rather that there is a strong overlap between them: A can and often does translate best as B, but not always. The same phenomenon occurs in translating between any two languages today; it is curiously difficult to pair words whose full range of nuanced meaning is identical in both cases.

The desire for balance or equation underpins several categories of Akkadian compilations which begin with the word ‘If’. This is no classification invented by me, for there is actually a Babylonian technical word that means ‘a composition beginning with the word “if”,’ – šummu. It derives from šumma, the normal word for ‘if’ itself, and we can see that the collected paragraphs of a law collection or diagnostic medical omens were known to librarians as the šummus.

Laws in codes such as that of Hammurabi represent the most stripped-down manifestation of the idea:

If a man put out the eye of another man, his eye shall be put out.

One deed or event leads unambiguously and inexorably to its consequence, in this case exemplifying the Bible-like eye-for-an-eye ruling (even if the literal penalty was not always exacted). This is straightforward. The same structural format of ‘If A then B’, however, applies equally to two much broader fields: divination and medicine.

Let us imagine that the king of Babylonia in the second millennium BC was contemplating a punitive raid over the Elamite border to the east. His first move would be to turn to his court diviner to establish whether this projected foray would go over well with the gods and which day would be fortuitous. The diviner’s training would lead him to identify sufficient diagnostic data on the various freshly extricated sheep’s organs (allowing for the internal hierarchy) to enable him to predict that the king should be victorious and Thursday should be good.

The diviner’s job under such circumstances was always complex: he had to tell the king authoritatively, in accordance with traditional lore and perhaps backed up with reference works, whatever he judged that the king wanted to hear without being obvious about it, and doing so in such a way that he and his colleagues always had a let-out in case of disaster. In a non-Versailles type of court the king, if a powerful man, might be served by a loyal court diviner who would do his best to manoeuvre conscientiously through the pitfalls; at Arabian-Nights Nineveh, where there was an abundance of talented and ambitious diviners with more than one agenda between them, it is not hard to imagine the subtle play of loyalty and testimony that would circle around all state-level omen taking; wonderful letters come out of that courtly world.

The same formal ‘If A then B’ structure is fundamental to Mesopotamian healing literature for,

(a) cause-of-symptom analysis by medical omens:

If a sick man’s body is hot and cold and his attack changes a lot:

Hand of Sin the Moon God.

If a sick man’s body is hot and cold but he does not sweat,

Hand of a Ghost, a message from his personal god.

(b) nature-of-symptom analysis to prescribe therapy:

If a woman has difficulty in giving birth, bray a north-facing root of ‘male’ mistletoe, mix in sesame oil, rub seven times in a downward direction over the lower part of her abdomen and she will give birth quickly.

If during a man’s sickness an inflammation affects him in his lower abdomen, pulverize together sumlalu and dog’s-tongue plant, boil in beer, bind on him and he will get better.

(c) nature-of-symptom analysis to predict outcome:

If his larynx makes a croaking sound he will die.

If during his illness either his hands or his feet grow weak, it is no stroke:

he will recover.

Predictions vary from ‘he will get better’ to ‘he will die’ with many variants in between.

Actually it has worried me for years that cuneiform scholars today invariably translate omen predictions within the ‘If A then B’ system after the model the king will triumph over his enemy, and medical prescriptions are made to promise he will get better. How is it that either system could allow certainty? Blithe predictions that someone will get better after a calculated interval or even an unspecified interval are probably more than any professional doctor would care to make nowadays. I think we must assume that all professional prognostications in ancient Mesopotamia were delivered with such riders as ‘in as much as we can judge …’ or ‘features like this tend to suggest …’ The whole process of taking or interpreting omens was, as I see it, delicately orchestrated with immense flexibility and subtlety, both physical and intellectual. We might also realistically assume that any military decision concerning a military plan which derived from omen work would never see the army setting out on a march there and then; level-headed input would always be required from the king’s chief of staff, who might privately have a low opinion of ‘gut-readers’ and much prefer their own sober assessment of arms, armour, chariotry and supplies before agreeing to any departure date.

To attribute such an interpretation to the verb form that provides the ‘B’ half of all this If-data is, in fact, quite permissible, for there is undoubtedly a shortfall in the Akkadian verb with regard to modality. This means that, for example, the verb form iballuṭ, ‘he will live’, or ‘he will get better’, can sustain a range of nuances that in English are ‘he could/might/should/ought to get better’. In today’s world all predictions are hedged around with uncertainty or escape mechanisms. I do not see for a moment how things could have been different in ancient Mesopotamia.

There is one unique discussion of these matters in cuneiform by the top people who actually did this work and shouldered very real responsibility. It was published under the title ‘A Babylonian Diviner’s Manual’ by the Chicago scholar A. L. Oppenheim, and to some extent it comes to our rescue. The author quotes the first lines of fourteen completely unknown and rather strange tablets of terrestrial omens and eleven of equally unknown astral omens. He then writes paragraphs – as if responding to three questions from a persistent interviewer with a microphone (which is, I suppose, what we are) – as follows:

Q. How does your science work?