It is common when discussing famous people to say they need no introduction. In the case of Jesse James this is both true and false. Jesse James is the most famous outlaw in history, but most of what the public “knows” about him is fable. Here is a brief overview of his life, along with the life of his older brother and fellow outlaw, Frank.

Frank and Jesse James were born in 1843 and 1847, respectively, on a farm near Kearney, western Missouri. Their father was a preacher who left for California’s gold fields while they were still children and died there. Their mother, Zerelda, a strong frontier woman, raised them on her own, with only minimal help from her second and third husbands. The third was the mild-mannered Dr. Reuben Samuel, who, while never quite a father figure to the boys, was loved by them.

Western Missouri n the mid- to late 1850s was a region at war. The question of whether the neighboring territory of Kansas would become a free or slave state led to violent action from the opposing factions. Missourians crossed the border en masse to rig territorial elections. This was eventually stopped, but the conflict grew ever more violent. Free-State guerrillas called Jayhawkers raided Missouri, killing slave owners and bringing their slaves back to Kansas and freedom. Missouri bushwhackers crossed the state line, killed Free-Staters, and destroyed abolitionist newspaper offices. The war between Jayhawkers and bushwhackers was the first chapter in the American Civil War and one of the main factors that led to the larger war. While the James family, being slave owners living close to the border, were lucky they didn’t lose their property, they certainly knew people who suffered.

Once the war started in earnest in 1861, Frank was quick to enlist, joining the rebellious Missouri State Guard that May. He saw action at the Confederate victory at Wilson’s Creek on August 10 and again during the successful siege of Lexington, Missouri, from September 11 to 20. The State Guard was then forced to retreat in the face of a superior Union force back to southwestern Missouri. Along the way Frank fell ill, got left behind, and was captured and paroled. In return for swearing not to take up arms against the Union, he was allowed to return home. He might have farmed peacefully for the rest of the war if it were not for General Order No. 19, enacted in July of 1862, which forced all able-bodied men, including paroled Confederates, to join local Union militias. Frank, like many others, couldn’t bring himself to don a Union uniform and fled. He joined the guerrilla band of William Quantrill.

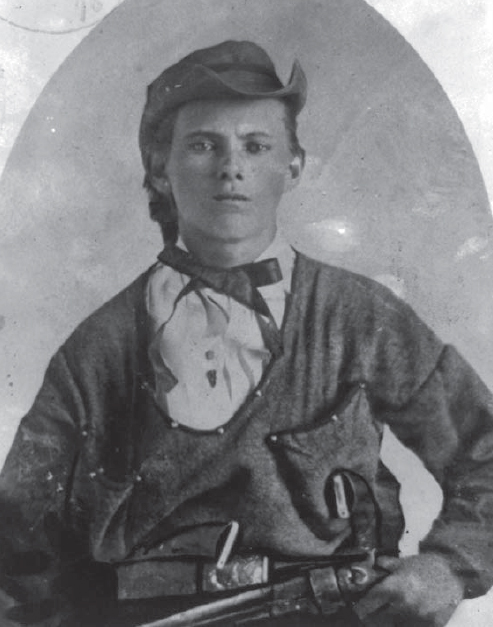

Jesse James as a teenaged Confederate guerrilla or “bushwhacker” in Missouri. This picture, taken July 10, 1864, shows him wearing a loose “guerrilla shirt” and wielding three Colt Navy revolvers, a favorite weapon among the bushwhackers and used by many outlaws after the war. This image is reversed and has led to the persistent misunderstanding that Jesse was left-handed. He was, in fact, right-handed. The photo was taken in Platte City, Missouri, when Jesse and other guerrillas raided the town to support a mutiny of the local Union militia. Three hundred militiamen changed sides and raised a rebel flag. (LoC)

Quantrill’s band was making a name for itself with its lightning hit-and-run tactics, ability to elude pursuit, aggressive fighting style, and its ill-treatment of Unionist civilians. To join, one had to show ability with a gun and horse and answer “yes” to the following questions, “Will you follow orders, be true to your fellows, and kill all those who serve and support the Union?”

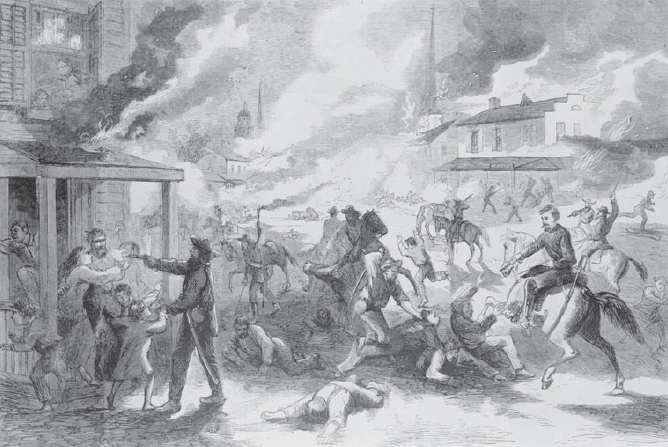

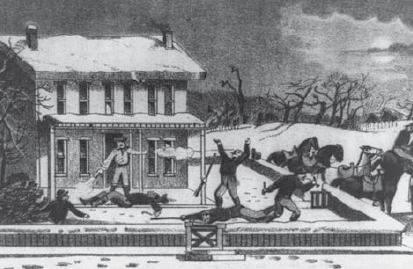

The Lawrence Massacre of August 21, 1863 by Quantrill’s group of bushwhackers was the worst atrocity against civilians in the war. The band descended on abolitionist Kansas, gunned down nearly 200 mostly unarmed men and boys, and burned the town. Frank James and Cole Younger were there that day, but showed little remorse in later years. (LoC)

It soon became known that the James family farm was a rest area for Quantrill’s guerrillas. The local militia (the same one Frank was supposed to have joined) showed up at the farm and demanded to know where Frank and his friends were. The soldiers beat Jesse, who was only 15, and tied a rope around his stepfather’s neck. They then hauled Reuben Samuel up, let him drop, then hauled him up again. Eventually he broke and revealed Frank’s hiding place. A brief skirmish ensued but the guerrillas got away. Samuel is believed to have suffered permanent brain damage as a result of his near hanging.

This incident instilled in Frank and Jesse a burning hatred of the North. Jesse was still too young to join the guerrillas, however, and they were probably not impressed when he shot the tip of his finger off while reloading a pistol. Being a good Baptist boy, he didn’t swear even under these trying circumstances and instead shouted out, “Dingus!” Dingus became his nickname for the rest of his life.

Meanwhile Frank was getting his revenge. Quantrill’s band rode roughshod over the region, raiding Lawrence, Kansas, on August 21, 1863, where they killed almost 200 mostly unarmed men and boys and torched the town. Frank was there that day, as was future outlaw Cole Younger. The massacre shocked both North and South and even some of the guerrillas didn’t like Quantrill’s methods. The band broke up that winter, some thinking Quantrill was too bloodthirsty and others thinking he was too much of a disciplinarian. These latter coalesced around Quantrill’s lieutenant, Bloody Bill Anderson. Frank went with Anderson, and Jesse, now 16, joined him in the spring of 1864.

Memories of the massacre lingered with Cole Younger. He joined the Christian Church on August 21, 1913, the 50th anniversary of the massacre. Explaining his actions long after the war he said:

My father was opposed to the war and had friends on both sides but was shot down in cold blood and robbed by a gang of federal freebooters as he was driving home from Kansas City. That day changed my whole life. The knowledge that my father had been killed in cold blood filled my heart with lust for vengeance.

This statement is only partially true. Cole had, in fact, joined the guerrillas before his father was killed by Union troops. This is only one of the many instances where publicity-hungry Cole tried to make himself look better for the press.

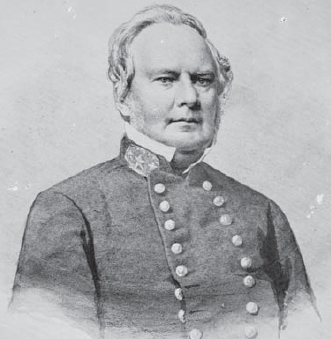

Jesse was shot through the lung that summer while trying to steal a saddle from a civilian. He recovered under the care of his cousin Zerelda. The two soon fell in love and he started calling her “Zee” so as not to have to use the same name as his mother. Within a month or two he was back in the saddle, in time to take part in Anderson’s bloody raid through central Missouri n support of a Confederate invasion led by General Sterling Price. Price moved up from Arkansas with 12,000 men in an ill-fated attempt to take St. Louis. Anderson’s raid left scores dead, including many civilians and unarmed Union soldiers, but Price’s invasion was repulsed.

As Price’s mangled army staggered back to Arkansas, Bloody Bill was killed by a plucky Union militia. Riding with him that day was future James–Younger gang member Clell Miller. He was only 14 at the time and was captured in the skirmish. Miller claimed he had been kidnapped by Anderson’s men and had only been with them for three days. This has been questioned by historians, but the support of several prominent neighbors and his tender age secured his release.

Gen. Sterling Price led Missouri Confederate forces on numerous campaigns. Guerrillas such as the James and Younger brothers supported his actions behind Union lines. (LoC)

At this point Frank and Jesse rejoined Quantrill. The guerrilla leader decided to lead his men to Kentucky to continue the fight; he even claimed he wanted to ride to the capital and assassinate Lincoln. Jesse, perhaps seeing the war was coming to an end, decided not to follow and remained in Missouri with some other guerrillas. Frank did follow, as did future outlaw Jim Younger, brother of Cole. Quantrill’s group was dogged by Union detachments. In one skirmish Jim Younger was captured but later escaped. On May 10, 1865 Quantrill’s band was run to ground by Unionist guerrillas as fierce as themselves. Quantrill was mortally wounded and at least two of his followers were killed. Frank James was lucky to get away with his life. Seeing the war was now truly at an end, Frank gave up on July 26.

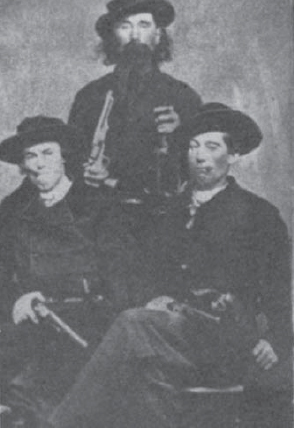

These bushwhackers from Quantrill’s group were Frank James’ and Cole Younger’s comrades-in-arms. Dave Poole, is shown standing, and seated are Arch Clements (left) and Bill Hendricks (right). The photo was taken while they were wintering in Texas. They didn’t like the image and trashed the photographer’s equipment. Clements rode with the James–Younger gang in their first heist, the Liberty bank robbery. He was gunned down later that year by the state militia while resisting arrest. (LoC)

Jesse had been riding with the remnants of Anderson’s old band in Missouri n the spring of 1865, but as the major Confederate armies laid down their arms, the hardcore bushwhackers began to give up hope. Some surrendered and found to their delight that they weren’t lynched. Others fled to the Far West. Jesse and a group of comrades tried to surrender at Lexington, Missouri, on May 15 and were fired upon by some jumpy Union soldiers. Jesse was shot through the same lung as before, and again nearly died. He formally surrendered on May 21. Again in the care of his family, he and Zee became secretly engaged.

Life for former Confederates was hard in Missouri. The state government banned them from voting, holding public office, or serving in several professions. Many returning Confederates, especially in the Ozark region, found their land had been taken from them for failure to pay taxes and was being now farmed by Unionists. Some ex-bushwhackers, unable to put the killing behind them, used this persecution as an excuse to turn to outlawry.

The first heist by the James–Younger gang was less than a year after the war, on February 13, 1866, when some ten to 13 men robbed the Clay County Savings Association Bank in Liberty, Missouri. It was owned by staunch Unionists, which made it more attractive to the former rebels than Liberty’s other, politically neutral, bank. The robbers got about $57,000 in what was the first American daytime bank robbery in peacetime. It’s unclear who made up the gang, but Cole Younger and Frank James are commonly believed to have been there. Despite popular tradition, Jesse probably wasn’t, because he was still laid up with his gunshot wound.

It is commonly believed that Jesse was in charge of the gang. He was certainly better known, thanks to his letters to various newspapers proclaiming his innocence. The more daring and better looking of the brothers, it is he who has become a legend, but it might have been Frank who was really in charge. Gang member George Shepard told a newspaperman, “Frank is the most shrewd, cunning, and capable; in fact, Jesse can’t compare with him. Frank is a man of education, and can act the fine gentleman on all occasions. Jesse is reckless, and a regular dare-devil in courage, but it’s Frank who makes all the plans and perfects the methods of escape. Jesse is a fighter and that’s all. Why, he can’t hardly read or write, and these stories about his writing to the Kansas City papers and the Nashville Banner is all stuff. If any letters were ever written, Frank wrote them.” [16–17]

Shepard added that Frank didn’t mind Jesse stealing the show because Frank, “would rather not be known, so he directs Jesse and Jesse directs the crowd. He [Jesse] likes notoriety and always takes care to let the people on trains know that he is the leader, and he always enjoyed the reading of his exploits in the papers.”

THOMAS COLEMAN “COLE” YOUNGER (JANUARY 15, 1844 – MARCH 21, 1916)

The oldest of the three outlaw Younger brothers, Cole grew up on a wealthy farm in western Missouri. He joined Quantrill’s guerrillas shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861. While he claimed he joined to avenge the murder of his father at the hands of a Union militia, in fact he joined months before that, although the murder certainly gave him a lingering hatred of the North. He also claimed he was a captain under the famous Confederate cavalry raider Brigadier General J.O. Shelby, but other than Cole’s own account, there is no evidence for this.

After the war, he helped found the James–Younger gang and participated in its first robbery, that of the Clay County Savings Association in Liberty, Missouri, in 1866. Cole went on to commit a series of robberies, both with the James brothers and independently with one or more of his brothers and other outlaws. While his main area of activity was Missouri, he may have participated in two bank robberies in Kentucky, another in West Virginia, a stagecoach robbery in Arkansas, and a train robbery in Iowa.

His age and greater wartime experience made him the dominant of the three brothers. Cole was said to have been level-headed, cool under fire, and didn’t like the more showy and hot-headed Jesse James. Cole could be showy himself, though. After his capture at Hanska Slough, he gave numerous and often contradictory interviews about his life, often stating he was sorry about the robbery, trying to clear his name of many crimes, and justifying the Lawrence Massacre.

After serving a 25-year sentence, he held various jobs including selling tombstones, running a Wild West show with Frank James, and going on the lecture circuit talking about how crime doesn’t pay. In 1903 he wrote the book The Story of Cole Younger by Himself: An Auto-biography of the Missouri Guerrilla, Confederate Cavalry Officer, and Western Outlaw. It’s a fascinating if unconvincing read. He is not known to have committed any crimes after his release.

Cole Younger was the most experienced of the outlaw Youngers and reportedly had doubts about the wisdom of the Northfield heist before, during, and certainly after the raid. Here he is shown shortly after his capture at Hanska Slough. The wound to his temple that knocked him out is clearly visible. (Northfield Historical Society)

On October 30, another bank was robbed in Lexington, Missouri, although the four robbers only got a little more than $2,000. On May 23, 1867, a dozen men robbed a bank in Richmond, Missouri. The robbers bagged some $3,500 but had to shoot their way out and left the mayor, the local jailor, and jailor’s son dead.

In the meantime Cole Younger had been developing a reputation as a robber with a string of heists to his name. He worked with both the James gang and his own people. Both gangs had a fluid membership and were only the “James–Younger gang” on certain jobs.

The interior and the vault of the Clay County Savings Association, Liberty, Missouri – robbed by the James–Younger gang in their first heist. (Sean McLachlan)

Jesse James captured the public imagination with his ability to fight off the law. This struck a chord with many rural Americans and former secessionists who mistrusted lawmen and anyone who represented the government or moneyed interests. While many of the stories about him were true, many more were invented or adapted from tales of earlier outlaws such as Dick Turpin and Claude Duval to embellish his exploits. Jesse encouraged this by sometimes signing his letters to the press using these names. (LoC)

Cole was born to a prosperous family near Lee’s Summit in Jackson County, Missouri, on January 15, 1844. A large, muscular man, he stood six feet, four inches, which was considered quite tall in those days. He was bright and friendly, yet easily aroused to volcanic anger. One man who worked with him in his later circus years said, “During my years on the frontier, and later in the Oklahoma oil fields, I have known many men with a command of profanity – freighters, cattle drovers, muleskinners, bullwhackers, and pipeliners. But none could approach Cole Younger’s brand of invective. Nor was there anything lacking in his personal courage.”

Like many former bushwhackers, Cole claimed that he was persecuted for his wartime activities. This seems to be an exaggeration, since the Youngers and Jameses at first lived openly at their family farms. The bushwhackers-turned-outlaws don’t seem to have suffered any worse than anyone else. In fact, being relatively prosperous, the Younger and James families were better off than many Unionists in a state where both sides suffered from the devastation of war.

Whether Cole Younger really tried to live within the law after the war is a mystery. He was involved in a bank robbery just one year after the war, but in 1868, he and another man captured two horse thieves and brought them to jail in Independence. Jesse James also struggled with his conscience. In September of 1869, Jesse asked to have his name struck from the membership of Mount Olive Baptist Church “for the stated reason that he believed himself unworthy.”

On December 7, 1869, the gang struck the bank at Gallatin, Missouri, killing a bank employee. The robbers bragged that they’d shot Samuel P. Cox, the militia commander whose unit had killed Bloody Bill Anderson. It turned out they got the wrong man, but this shows there was some political motive beyond just grabbing easy money. A horse left behind was traced to Jesse. The law converged on his family farm but the brothers shot their way out.

It was at this time that Jesse began his letter-writing campaign to the Missouri papers, especially the Kansas City Times, where John Newman Edwards was editor. Edwards had ridden with Confederate cavalry raider J.O. Shelby during the war and saw the young ex-bushwhacker as the perfect new hero for the unreconstructed South. More robberies followed, with the gang expanding into Iowa and Kentucky. Their greatest escapade was robbing the cashbox of the Kansas City Exposition on September 26, 1872. This was done in front of a huge crowd and this daring act, along with Edwards’ glowing newspaper account of the robbery, did much to create their fame.

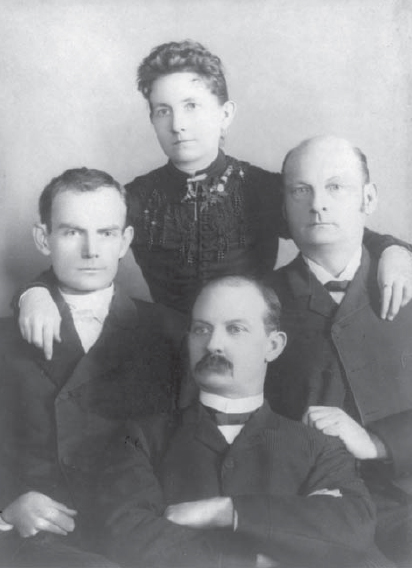

Group picture of the Younger family. Clockwise from left: Robert Younger, Henrietta Younger, Cole Younger, and James Younger. Henrietta was one of the outlaws’ sisters and worked as a schoolteacher. (LoC)

Their notoriety increased on January 3, 1874, when they robbed a train at Gads Hill, Missouri. This hamlet had only 15 citizens. Five members of the gang, all wearing hoods, rounded up the entire population and put them under guard while they robbed the only store. As the train approached, one outlaw flagged it down with a red flag. The train stopped, the gang pulled out their revolvers, and made off with about $4,000 from the express mail and a few hundred dollars from the passengers. The technique of rounding up the locals to keep them from causing trouble and using a red signal to get the train to make an emergency stop was a signature of the gang. It is thought that one or more of the Younger brothers rode with the James brothers on this heist because the outlaws fled to St. Clair County, where the Youngers often hid out.

The James–Younger gang was not the first to rob a train in peacetime. That dubious honor goes to the Reno gang of Indiana, whose first train heist was on October 6, 1866. Gads Hill was Missouri’s first peacetime train robbery, however, and predictably made headlines across the state.

The Younger brothers – Cole, Jim, John, and Bob – were treated as prime suspects. John Younger was already wanted over the 1871 killing of a Dallas lawman who had been trying to arrest him over a shooting. Now two Pinkerton agents and their local guide went to the Youngers’ neighborhood to track them down over the Gads Hill affair. They were bushwhacked by Jim and John Younger. John Younger, one of the Pinkertons, and the guide were all killed in the ensuing gunfight. Another Pinkerton tried to catch the James brothers by foolishly showing up at their farm posing as a laborer looking for work. His body was found by a road many miles away.

The James and Younger brothers moved around constantly, Jesse and Frank keeping in contact with their family by letters written in code. Despite the price on their heads, the Jameses often visited home, their frightened neighbors not daring to report them to authorities. On the night of January 25, 1875, a group of agents surrounded the James farm and threw a firebomb through one of the windows. It exploded, killing Archie Samuel, Frank’s and Jesse’s half-brother, and destroying their mother’s hand. The James brothers were not at the farm that night, and the attack drew widespread condemnation against the Pinkertons and fueled the James legend even more. The Hannibal and Saint Joseph Railroad, which had transported the Pinkertons on a special train that night, gave Mrs. Samuel a free lifetime pass for her and her companions. It was never robbed by the gang.

The James farm and (above) the window through which the Pinkerton bomb was thrown. This attack, which killed Frank and Jesse’s half-brother and maimed their mother, did much to bring national sympathy to the “James boys.” (Sean McLachlan)