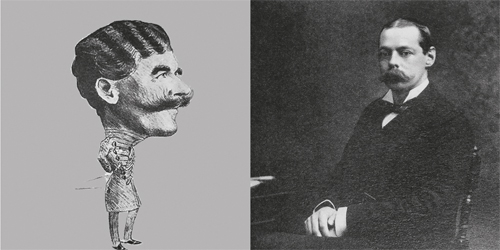

This is the only likeness of Churchill actually done in Cuba during his stay. It is not known if it was drawn from life during an interview or from a photograph. It is an anonymous piece of Spanish propaganda work of the time.

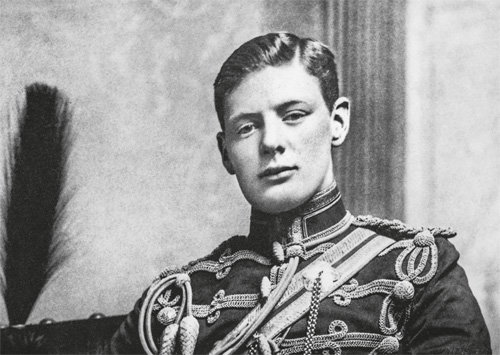

A well-known photograph of Churchill in 1895 in the full dress uniform of the 4th Hussars.

Colonel John Brabazon (left), Churchill’s first commanding officer, who backed him in his bid to join his cavalry regiment; and (right) Lord Randolph Churchill, who wanted him to join the infantry.

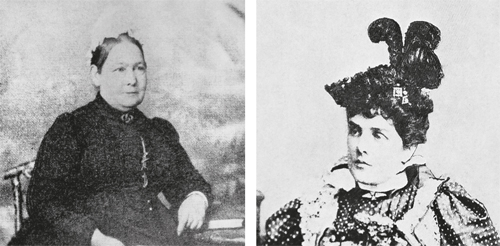

Mrs Everest (left), perhaps the most beloved woman in Churchill’s early life and whose photo hung in his office even during the Second World War. And (right) Lady Randolph Churchill, Jennie, Winston’s American mother who needed convincing in order to back the Cuba project.

Lieutenant Reginald Barnes (Reggie) who was easily convinced to join in the adventure. (Photo courtesy of Queen’s Royal Hussars)

Through a truly exceptional series of coincidences, any possible opposition from Lord Wolseley as commander-in-chief was avoided.

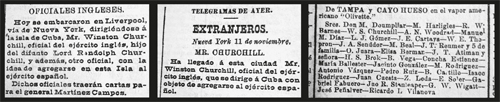

Three contemporary excerpts from Havana’s pro-Spanish Diario de la Marina, from the editions of 3, 12, and 20 November 1895, showing, respectively, the officers’ departure from Liverpool, arrival in New York and arrival in Havana.

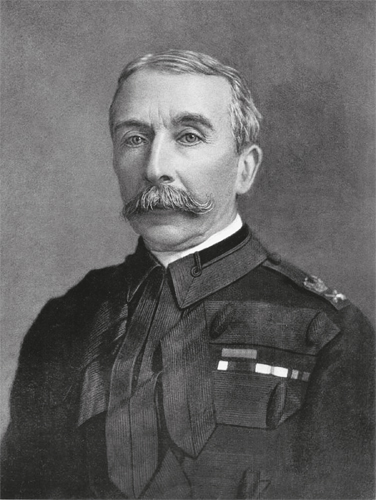

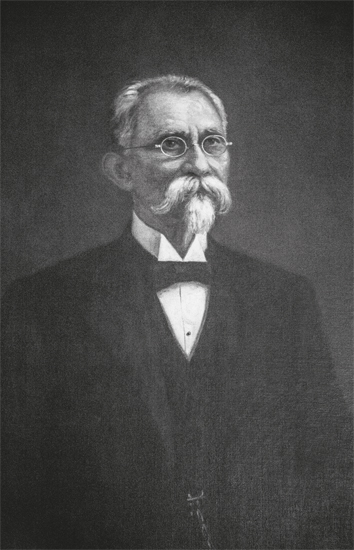

Major-General Sir Edward Chapman, Director of Military Intelligence at the War Office, gave Churchill his first official military task beyond regimental duties.

Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, ambassador in Madrid, an old friend of the Churchill family, played a key role.

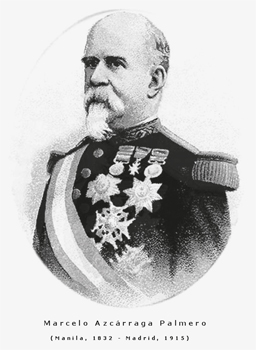

General Marcelo Azcárraga Palmero, Minister of War, accepted speedily Drummond Wolff’s request.

Churchill in tropical uniform, seen here in India some months after the Cuba trip.

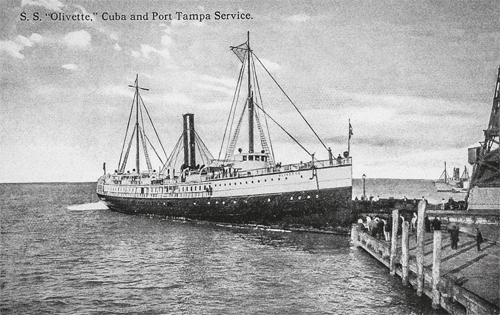

The American passenger ship Olivette carried the two young officers from Tampa to Havana. (Author’s collection)

The Morro Castle, guardian of the harbour of Havana, and first sight of Cuba for the young officers. (Glen Hartle)

The Gran Hotel Inglaterra, where Winston and Reggie stayed both before and after their experience at the front, shown with one storey more than in 1895 but in other respects looking much as it did. (Glen Hartle)

The Palace of the Captain’s General of Cuba, in wartime used as their military headquarters. It is not certain if General Arderíus received the two officers here or in his own building next door. (Glen Hartle)

Major-General José Arderíus y García, second in command in Cuba, was the first Spanish officer the two Englishmen encountered. He hoped to make the most out of the propaganda opportunity presented by their visit.

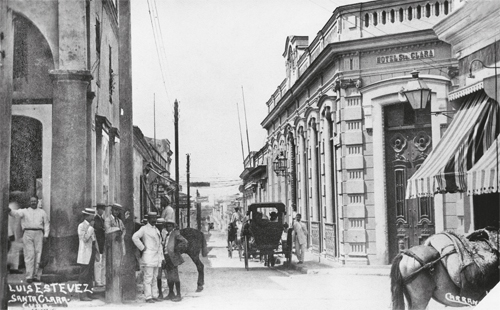

After their re-routed train journey from Havana, the two officers alighted at the train station in Santa Clara, looking today much as it did then. (Glen Hartle)

Captain-General Arsenio Martínez Campos y Antón received Winston and Reggie at his headquarters across the square from the train station.

Martínez Campos’ headquarters in Santa Clara. (Glen Hartle)

The famed trocha or trench line dividing eastern from western Cuba and centrepiece of the Spanish defence system. This photograph shows a typical blockhouse though slightly improved from how it would have looked in 1895. (Glen Hartle)

The train station in Cienfuegos where the two officers arrived on 21 November, and the city from which they sailed the next morning, seen today but with virtually no change from 1895. (Glen Hartle)

The Tunas de Zaza railway station virtually unchanged until today from whence the two officers finally departed for Sancti Spiritus. (Glen Hartle)

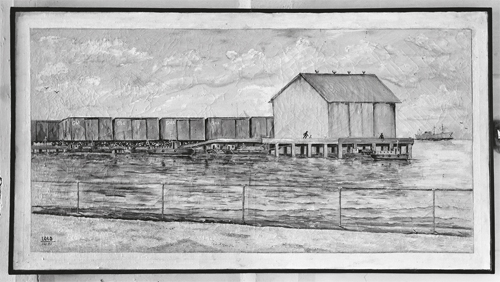

A nearly contemporary painting of the main pier at Tunas de Zaza, at which Churchill and Barnes alighted. (Photograph by Glen Hartle)

The Escambray Mountains as seen from the train between Tunas de Zaza and Sancti Spiritus, a zone judged by Churchill to be ‘The most dangerous and disturbed in the whole island’. (Glen Hartle)

Again in the Spanish colonial style, the railway station at Sancti Spiritus where Winston and Reggie arrived to meet the Suárez Valdés column. (Glen Hartle)

The Fonda el Correo, where Churchill and Barnes stayed in the town Winston described as ‘a forsaken place’, is no longer extant. But the rest of the buildings he would have known on San Rafael Street are mostly still there. (Glen Hartle)

Divisional General Álvaro Suárez Valdés, commander of the column with which Barnes and Churchill travelled to their baptism of fire, described by Winston as ‘a man of great courage’.

A scene typical of the countryside through which the column marched. (Glen Hartle)

Remains of the ‘road’ along which the column travelled from Sancti Spiritus to Arroyo Blanco. (Glen Hartle)

The first view of Arroyo Blanco from the road on which the column was travelling. (Glen Hartle)

The main Spanish military building in Arroyo Blanco, pictured here, was used for headquarters, logistics and command and control requirements. Father Benito’s manse is to the left, just out of the picture. (Glen Hartle)

Máximo Gómez, the exceptional commander of the insurgent forces in both major wars for independence.

General José García Navarro, commander of the advanced guard of the column.

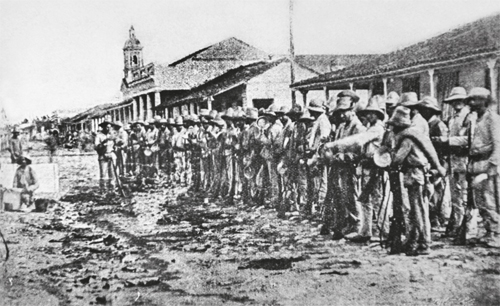

The troops of Navarro who so impressed Churchill are seen here in Colón some two weeks after La Reforma battle. It is not clear whether these are from the battalion of the Cazadores de Valladolid or the Regimiento de Cuba.

The route taken by the column upon leaving Arroyo Blanco on Churchill’s 21st birthday. (Glen Hartle)

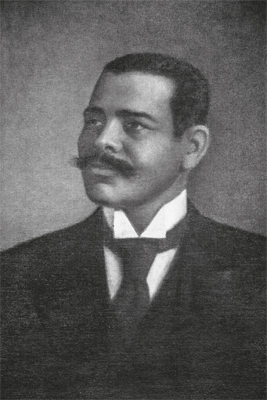

Antonio Maceo Grajales, second in command of the rebel army, commanded directly the force with which Churchill’s column was engaged at La Reforma, and was only a few hundred metres from Winston during the fighting.

The river crossing point where the Spanish attack aimed to disrupt the withdrawal of the impedimenta and prevent their joining the main rebel column as it moved west. (Glen Hartle)

The Spanish column’s lead battalion, the Regimiento de Cuba, deployed on this ground and came under rebel fire from the slopes in the distance. (Glen Hartle)

Churchill’s own sketch, improved by A.L. Crowther at The Daily Graphic, depicting the deployment and firing by the Spanish guns on the rebels at La Reforma, 2 December 1895.

The centre of the insurgent ‘position’ is now marked by a monument to all three of the battles that took place at La Reforma. (Glen Hartle)

Only a few small houses remain of the Jicotea of Churchill’s time. (Glen Hartle)

Spanish central headquarters at Ciego de Avila where almost certainly Suárez Valdés lunched with the two officers before heading out of the war zone. (Glen Hartle)

Ruins of one of the blockhouses Churchill would have passed on the rail line between Ciego de Avila and the port of Júcaro. (Glen Hartle)

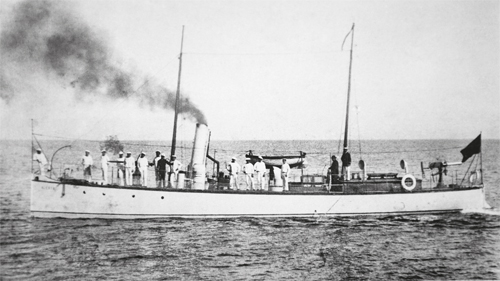

An Alerta class gunboat like those on which Churchill and Barnes travelled from Júcaro to Tunas de Zaza and Cienfuegos on the journey back to Havana.

The locomotives used by the Spanish on the trains from Tunas de Zaza to Sancti Spiritus, seen here at their base the year of Churchill’s visit. (Photo courtesy of Antonieta Jiménez)

The Hotel Santa Clara where it seems very likely Churchill and Barnes stayed the night of 4/5 December 1895 on the way back to the capital. (Courtesy of Arnaldo Díaz)

Lieutenant Félix de Vidal, the only other foreign attached officer serving alongside the Spanish during 1895–96. Note the similarity between his tropical uniform and that of Churchill.

The Cruz Roja por Mérito Militar, the medal awarded to both officers by the Queen Regent in recognition of their behaviour under fire.

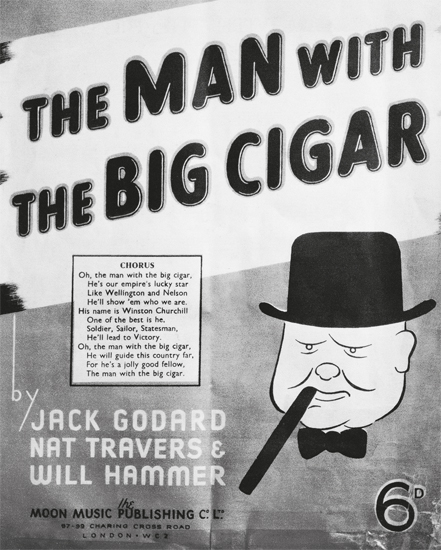

A Second World War musical poster and song sheet with Winston’s cigar in the place of honour. Winston did not get to know cigars in Cuba but he did begin a lifelong love affair with the exceptional Cuban examples. (Author’s collection)

On top of the more recent ‘Churchill’ cigar is seen a Romeo y Julieta, one of his own favourites at the time. (Glen Hartle)

Father Benito, the village priest, lived in this manse and may well have received the two young officers during their time in Arroyo Blanco. (Glen Hartle)

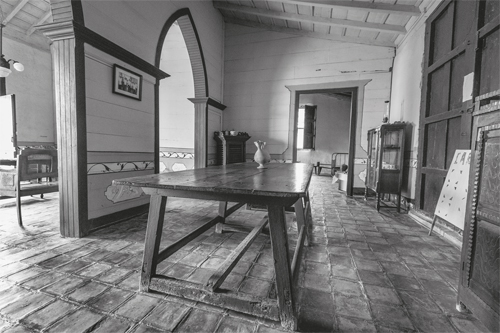

Frequently termed ‘the Churchill Table’ by those inclined to believe in local mythology, it is nonetheless quite possible that Churchill did indeed dine with Father Benito in this room and at this table. (Glen Hartle)

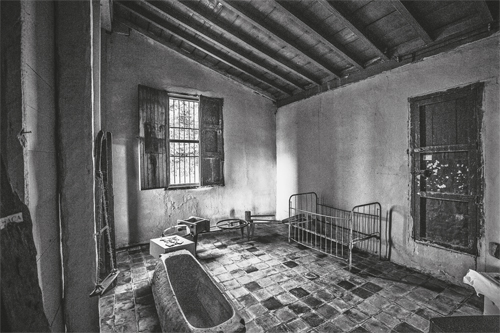

Given Churchill’s life-long love affair with his bath, it is also possible that local legend is right in saying that he took advantage of the priest’s bathtub while in Arroyo Blanco. (Glen Hartle)

This 1895 print shows clearly an officer in the tropical uniform of the 4th Hussars of the day. This is doubtless the uniform Churchill wore in Cuba.

This stamp shows the ‘jubo’, the Cuban snake to which Churchill refers as a means to conduct the torching campaign of the sugar cane fields by the rebels. There is no truth to this story.

The much-respected 1893 Mauser (Argentine model). It was this rifle that fired the round Winston had in part come to check out for the War Office. British Imperial forces were to face both rifle and round four years later in the Boer War.

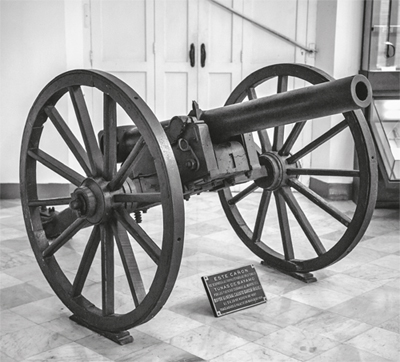

The Spanish used almost exclusively the Krupp 75mm mountain gun for their operations in Cuba. It was this gun that the artillerymen of the Suárez Valdés used at La Reforma.

Only some of the many different rifles and muskets used by the rebel army are seen here.

The railway station at Santo Domingo where a pilot engine and an armoured car were added to Churchill’s train. From here on in the journey to the front insurgent action against such trains could be expected. (Glen Hartle)

The fearsome Cuban machete, respected not only by Churchill but by all ranks of the Spanish Army who at any time had to face it in battle. This one is in the museum of the Palace of the Captain’s General in Havana and belonged to General Antonio Maceo. (Glen Hartle)

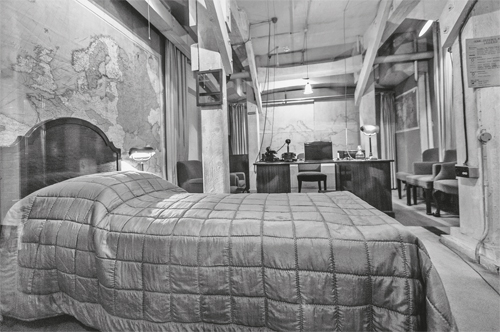

The bed in the Cabinet War Rooms in London in which Churchill took his famous siestas and was thus enabled to carry on working late into the night.