The earth is yours and the fullness thereof.

The Olivette had a peaceful passage to Havana, described by Churchill as ‘comfortable’, stopping briefly at Key West to pick up further passengers and mail, although, just before dawn on 20 November, what Churchill called a ‘violent storm’ broke on the vessel waking the young officer up but allowing him to be on deck when the ship approached Cuba and the glorious harbour entrance to Havana. The scene then and now is dominated by the brooding height of Morro Castle, standing to the port side at the entrance to the narrow slip of nearly 2km of water that constitutes the only means of reaching the huge inner harbour from the sea. Built in 1589–1609, the giant defence work, sometimes called Drake’s Castle because it was reputedly built as a defence against Francis Drake’s continuing threats to Havana, is the largest fortification in the insular Caribbean. Across from it to starboard lies Punta Castle, low-lying and menacing for any enemy daring to approach the city.

Churchill was suitably impressed. Although he termed Morro Castle only of ‘formerly great strength’, since modern technology had already put most of its advantages out of play, he still said that it ‘commands the channel to the port’, and later waxed romantic about how he felt as they reached their destination:

When first in the dim light of early morning I saw the shores of Cuba rise and define themselves from dark-blue horizons, I felt as if I sailed with Long John Silver and first gazed on Treasure Island. Here was a scene of vital action. Here was a place where anything might happen. Here I might leave my bones … Cuba is a lovely island. Well have the Spanish named it ‘The Pearl of the Antilles’. The temperate yet ardent climate, the abundant rainfall, the luxuriant vegetation, the unrivalled fertility of the soil, the beautiful scenery – all combined to make me accuse that absent-minded morning when our ancestors let so delectable a possession slip through our fingers … The city and harbour of Havana … presented a spectacle … in every respect magnificent.1

He refers in his lamentation here to the situation at the end of the Seven Years War in 1763 when Cuba was returned to Spain partly in exchange for Florida under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. In fact, only Havana and the west of the island had been effectively taken by the British in the 1762 campaign, and the rest of the colony was still resisting British occupation.2 Be that as it may, Winston was immediately taken by Cuba, a country for which he had a special regard for the rest of his life.

On arrival, his letters of introduction immediately proved their worth. Both officers were carrying their pistols in their luggage, and such weapons were subject to the strictest of controls, as can be imagined on an island with a serious insurgency. Customs officials would normally have taken a dim view of these weapons, but Churchill recounted to his mother how, once the proffered letters from high Spanish authorities were read by the local officials, they were let through at once with their weapons. They hired a carriage and were driven through the peaceful streets to their hotel, the Gran Hotel Inglaterra, a mile or so away. Though Churchill describes the hotel as only ‘fairly good’, it was one of the very best in the city, if not the best, and its location was sans pareil. On the main square of what was then the ‘new’ city, just across the park from what is now called Old Havana (La Habana Vieja), the Hotel Inglaterra played host to virtually all the main visitors to the capital.

In addition, the hotel was the prime place to stay for journalists covering the island and most of those covering the war were lodged there or close by. Even more importantly, the Louvre Café, on the principle street terrace of the hotel, was the main café and meeting place of the most important government and business people in the city. Even today it is central to the city’s life but in the mid-1890s one could frequently see the Captain-General or his senior officers there, mixing with the other powerful people of Havana’s vibrant life. It was close to both the main opera houses and the Prado which, like Barcelona’s, was and is a main artery leading from the higher centre of the city down to the sea. Churchill was where he should be, and was expected to be, as both a journalist and a scion of a significant British aristocratic family. After the voyage and before any official duties, Barnes and Churchill sat down to eat some fresh oranges and to have a very first Havana cigar in that most valued of future Churchilliana’s home town.

Alexander Gollan, the British consul-general, had been at the pier to meet them. Gollan was the classic ‘old Latin America hand’ in the British Foreign Service. Born in Inverness in Scotland in 1840, he was first posted as a young lad to the British vice-consulate in Pernambuco, Brazil, in 1856. By the time of his next move, in 1867, he was vice-consul in that city, and he had married a Brazilian. Posted then to Coquimbo in Chile, he subsequently moved on to Greytown in Nicaragua. Speaking by now both fluent Spanish and Portuguese, he was next sent to the important post of vice-consul for Rio Grande do Sul in southern Brazil, a place of considerable British trade and investment. In 1885, he left Latin America, but not the Spanish-speaking world, when he became consul in Manila, where he was to stay for seven years. From there he went in 1892 to Cuba as consul-general. By 1895 he was well known and well connected in Havana and, as opposed to his predecessors in the days of slavery, he had no duties as consul-general that the locals resented. British consuls before 1889 had a major responsibility for keeping an eye on the slave trade which Britain and the Royal Navy were sworn to stamp out, and Spanish and Cuban officials, as well as much of the aristocracy of the colony, did everything they could to avoid British attempts to end the trade and, in the bargain, to make the job of the British consul-general as close to impossible as it could be made. This was by now a thing of the past for most Cubans and Gollan was influential in helping many British subjects, and perhaps especially journalists, pass their time in Cuba profitably. Gollan was to be rescued by HMS Talbot in July 1898 when he and a number of other starving war refugees were evacuated by the Royal Navy from a Havana then under siege by the US Navy.

He had clearly heard from Drummond Wolff in Madrid of the officers’ arrival, although he would in any case have had the information from the major Havana papers, which had covered Churchill and Barnes’ journey from their departure from Liverpool, such was the perceived importance of this visit to the island.3 A short note in the Diario de la Marina, the official government paper but also the most widely read, was followed by articles on Churchill’s arrival in New York (Barnes was not in this one) and their arrival in Havana. The phrasing of the articles could easily give the impression of British, or at least Churchill and Barnes’, desire to serve alongside the Spanish Army in the suppression of the revolt. On departure from Liverpool, under the title ‘British Officers’, appeared the following short bit of news:

Mr Winston Churchill, officer of the British Army and son of the late Lord Randolph Churchill, embarked today in Liverpool, via New York, for the island of Cuba with another officer with the idea of adding themselves [agregarse] to the Spanish Army on the island.

And on arrival in New York, in an announcement dated 12 November under the title ‘Mr Churchill’, appeared the following: ‘Mr Winston Churchill, a British Army officer, is heading to Cuba with the object of joining [agregarse] up with the Spanish Army.’ The news of Churchill’s arrival was available for anyone interested in Cuba and the way it was phrased gave a clear impression that he, both officers or even the British government were in favour of the Spanish cause and against the insurgency.

In 1895, a situation such as the one from which Gollan was later rescued seemed impossibly remote. The city was calm and there was no sign of war to be seen, although the state of war prevailing meant, as he complained to the Foreign Office in London, that Gollan had had no leave in that year.4 The diplomat greeted the two officers warmly and told them that he had already arranged for them to see the second-in-command of the colony, the Segundo Cabo, that very afternoon. Major-General José Arderíus y García was an interesting officer. Like several others serving in Cuba, he had actually been born on the island.5 He had likewise fought there in the Ten Years War of 1868–78 and knew the island very well. He was, in a way common in the Spanish Army of the late nineteenth century, the brother-in-law of the captain-general, Arsenio Martínez Campos, who was then in Santa Clara, some 270km from Havana, where he had moved his field headquarters on 4 November in an attempt to bar the route to the advance of rebel forces from the east towards the richer lands of western Cuba.

Arderíus is a little-known figure who deserves to be better studied. When he had had the opportunity to be acting captain-general from July to September 1893, he had used the occasion, with peace still prevailing, to bring together ex-rebels from the previous conflict and senior Spanish military officers and other officials, to talk about the future of the colony. The former rebels stated at the meeting that the situation was in fact quite clear: if there were meaningful reforms, Cuba would remain loyal; with no such reforms, renewed revolution was inevitable. Arderíus probably agreed with this view but too few in Madrid or even in Havana listened. The initiative itself, however, was both an interesting and a courageous one for an acting Captain-General in office for such a brief time.6

The general received the two young officers and their accompanying diplomat at his headquarters a few hundred metres from the hotel at the Plaza de Armas, the central square of the old city. The trip to his HQ would have been an eye-opener for the two newcomers as it would have reinforced their view of the city as one at peace. They did see many soldiers, although many of them would have been the voluntarios (volunteers) to whom Churchill makes reference in his first ‘letter from the front’ written for the Daily Graphic in Cienfuegos a couple of days later. But they were about the only sign of an on-going war they were to see in the capital. Arderíus had received some time earlier news of the arrival of the two British officers and may even have been behind the extra coverage given by the press, itself controlled to a high degree, to their coming. As Churchill himself suggested in his first dispatch, the control of the press was almost total:

The town shows no sign of the insurrection, and business proceeds everywhere as usual … What struck me most was the absence of any news … London may know much of what is happening in the island – New York is certain to know more – but Havana hears nothing. All the papers are strictly edited by the Government and are filled with foreign and altogether irrelevant topics.7

More proof of governmental control of the press, and of Spanish interest in turning the visit to their account, were two full articles in papers with an even more pro-government line than the rest. In an article published the day after their arrival, in the section of the newspaper called ‘News of the War’, thus linking in the reader’s mind the relationship between Churchill’s arrival and the conduct of the war, and under the title ‘Mr W.S. Churchill’, the Diario del Ejército (the army newspaper) positively gushed:

The Army Newspaper is pleased to greet and give a welcome to the young British officer who has come to share with our comrades in arms the pains of the campaign with the object of studying this, from so many angles, so special war. Our military colleague tells us that British officers are accustomed to operate in the most diverse climates, and to make war in all the countries of the world where man is found, and we do not doubt that Mr W.S. Churchill will obtain in Cuba great lessons, and will see the difficulties that are presented to a regular army when the enemy he confronts employs the tactic of fleeing a fight at the first sign of the lightest resistance, and he will observe on more than one occasion one of the virtues of the Spanish soldier: sobriety and endurance to suffering …

We wish this illustrious officer that he may be pleased living among us and that he makes for himself the same brilliant career in arms as his father did in the politics of his country.8

This article spent half of its space describing Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph, making certain that the importance of the visit was not so much in that of an unknown second-lieutenant but in the quality of the person that second-lieutenant represented and his background. It is not known if Churchill and Barnes saw this article at this time but Winston must have been perplexed to be described as an ‘illustrious officer’ if he could hardly be displeased to see his father so praised.

General Arderíus welcomed the two officers, gave them advice on the trip to Santa Clara, and assured them that he would advise General Martínez Campos immediately of their coming. He treated them, Churchill wrote later, as ‘an unofficial, but nonetheless important, mission sent at a time of stress by a mighty Power and old ally’. The two officers tried hard to dispel any such notion but their protestations had the opposite effect. The Spanish would not, if they could help it, take this visit as anything but a chance to suggest that Britain was, or at least these two British officers were, very sympathetic to Spain’s plight.9 They were then dismissed back to their hotel, from whence they saw a little of Havana and Churchill wrote his first letter home to his mother as well as another to Bourke Cockran.

During the Boer War, half a decade after the Cuba visit, Winston Churchill, the still-young war correspondent, reached pan-imperial hero status with his well-known adventure with a British Army armoured train, his capture by the Boers, and his spectacular escape from their prisoner-of-war camp and return to British territory through neighbouring Portuguese East Africa. His own account of those events still makes stimulating reading: London to Ladysmith: Via Pretoria was published immediately after his return to London in 1900. What is much less known is that his first contact with the phenomenon was not in South Africa but in Cuba five years earlier. The Spanish Army was in general quite capable of holding onto the main and even the secondary towns of Cuba but, as so often in counter-insurgency campaigns, it had no such control over large parts of the countryside. The level of support of the Cuban people for the idea of independence, as Winston himself quickly noted and wrote about in his letters, had grown to a level nearly universal. Continued misgovernment and the failure to honour the promises of reform made to islanders in the government’s bid to win the first war for independence meant that the continuation of rule by Madrid had received near general rejection by Cuban-born people. And, whereas in the first war most Cubans, especially in the west, not only remained loyal but frequently fought for Spain against the rebels, this was not the case in the final struggle.10

This meant that the Spanish Army had to provide logistical support for its far-flung army garrisons with a system of trains and mule- or oxen-based convoys that brought them all the needs that were difficult for them to obtain in a hostile and often barren countryside. The extensive rail system that western Cuba enjoyed helped with this and, because of the great wealth engendered by the sugar industry, and the need for that product to be transported by rail, Cuba could boast one of the best in Latin America by 1895. Cuba in fact had its first railway as early as 1837, when a line was opened between the capital and the rich sugar town of Güines, years before metropolitan Spain had one. The mambises were not stupid, however, and realised that not only were the Spanish dependent on the railway but that trains were vulnerable to insurgent attack at many points and were often the source of the rich booty that the rebels needed to survive and continue the war.

Churchill and Barnes were to see right away the advantages and disadvantages of railway dependence for an army when they headed off to Santa Clara the day after their arrival on the island. The first point to remember here is that Spanish strategy was stymied by a perceived need to not only field an army to engage the main rebel forces but also to garrison the many towns and villages of Cuba while also putting very small garrisons of regular troops and/or voluntarios onto the rich but vulnerable sugar plantations of the island. This sapping of the regular army, and the reduction in its capacity to field sufficiently significant forces for operations other than static ones of local defence, was a highly detrimental effect of the policy of showing local landlords that they would be defended in case of rebel raids. Since, for reasons we will later discuss at length, the mambí army was mobile and rapidly moving, neither objective was truly achieved. The army’s small detachments often proved entirely unable to deter or defeat enemy raids because the rebels did not attack unless they enjoyed the element of surprise added to superior numbers. But, despite the huge army Madrid deployed, the deployment of such small garrisons meant that there were never enough soldiers to field an army of operations that could best the rebels in sustained combat.

On the morning of 21 November the two British officers boarded a largely unarmoured civilian train in Havana bound for Santa Clara, normally a twelve-hour trip. As Churchill remarked in his first ‘letter’ for publication in The Daily Graphic, at first the train moved along normally as there was little fear of rebel attack for some time after leaving Havana. But after Colón, a big farming town in the province of Matanzas, little more than 100km from the destination, the danger of attacks on the train increased. The rebels would attack with rifle fire or dynamite or just prepare a trap of some kind causing the train to derail. Thus a pilot engine and armoured car were added to trains as they went through Santo Domingo, still over 70km from Santa Clara, and an escort of soldiers now travelled in the last carriage. At this stage of his career Winston appears to have been quite pleased with the idea of an armoured train. In the South African War, five years later, he criticised them heavily:

Nothing looks more formidable than an armoured train; but nothing is in fact more vulnerable and helpless. It was only necessary to blow up a bridge or culvert to leave the monster stranded, far from home and help, at the mercy of the enemy.11

This assessment applied in Cuba as well, although the rebel enemy had no artillery or machine guns, as did the Boers, to take advantage of the train’s vulnerability to the maximum. By the end of his time in Cuba Winston was already having doubts.

The trip eventually took more than nine hours because, shortly after passing through Santo Domingo, the young officers learned that the line had been cut. They were therefore obliged to take a more roundabout route via the village of Cruces, some 30km to the south, causing greater delay. But worse news was to come. The train in front of theirs, carrying the very officer with whom they were to spend time in a couple of days, Major-General Álvaro Suárez Valdés, had been derailed by enemy action in what the Spanish newspapers immediately began to call a rebel attempt to assassinate the general. A number of Spanish soldiers had been wounded. This was getting close to the real thing. Danger lurked around every corner and Winston was clearly loving the experience.

With the train creaking into Santa Clara well behind schedule, though not all that late in the day, Churchill and Barnes were met by a staff officer who took them across the square to a large and handsome military building housing the field headquarters of the captain-general. General Arsenio Martínez Campos y Antón was in fact a field marshal and a very senior officer indeed. His background was legendary in both Cuba and Spain.

Born in Segovia in 1831, he had joined the army as soon as he could. He served in the African War with Morocco in 1859–60 and in Mexico in the intervention of 1861–62, where he distinguished himself on the staff of the expedition commander, Lieutenant-General Conde de Reus. He was made brigadier in 1869 at only 38 years of age in the peculiar conditions of that year when the Bourbon monarchy fell and a short-lived republic was ushered in. He was involved in suppressing a rebellion at home in 1873, and gave his own decisive push conducting a pronunciamiento, known as the Conspiracy of Sagunto, which brought the Bourbon dynasty back to the throne.12

In 1876, he was named Captain-General of Cuba at a decisive moment in the Ten Years War, and conducted an exceptionally humane ‘carrot and stick’ campaign which ended in less than two years in the total defeat of the rebels under the same Máximo Gómez and Antonio Maceo he was trying to tackle when Churchill and Barnes arrived at his HQ in Santa Clara. In the famous Pact of Zanjón in 1878 the key remaining rebel leaders surrendered in return for promises of reform in the colony and a degree of democratisation as well as autonomy for Cuba. Though desultory fighting still persisted for some months under recalcitrant leader Maceo, that ‘war’, termed the Guerra Chiquita in Cuban history (‘small war’, to distinguish it from the grande or Ten Years War), ended in a fizzle. Martínez Campos became a hero to Spaniards and Cubans alike as peace was restored, prosperity slowly returned and reforms were begun. Soon, however, as we have seen, Madrid backed down on the reforms and no real progress was made, despite Martínez Campos’ attempts to use his influence to ensure his promises to the Cuban rebels were honoured; even his time as a minister in a short-lived government in 1879 could do nothing to make progress with colonial reform. Only his commitment to the abolition of slavery was to eventually prosper.

In 1893 Martínez Campos was given command of Spanish forces in North Africa, where Spain had few possessions but ambitions to increase their number. Here too he did a good job and his reputation grew. He was therefore first given the captaincy-generalship of Castilla la Nueva, a quiet post, and then the captaincy-generalship of Cataluña, the troubled province of great industrial wealth on the north-west border with France and a hotbed of separatism, republicanism, trade unionism and anarchist terrorism. While there, a short sharp war broke out with the Carlists, a right-wing monarchist grouping backing another pretender to the Spanish throne, and once again his humanitarian handling of the conflict increased his prestige. The same heightened reputation continued when he was then sent to command the Spanish troops in the Melilla War of 1895, another short conflict concerning a Spanish outpost on the northern coast of Morocco.

His return to Cuba after the outbreak of the new revolution reassured those who wished for a quick suppression of the rebellion and a rapid return to a state of peace. Here was the victor of 1878 and the humanitarian reformer all could trust. It was this man, now a 64-year-old marshal, both fatter and older than in his heyday seventeen years earlier, who received the two subalterns in his office, in the middle of a war that was not going at all well despite his taking charge, that late November day in 1895.13 If he was troubled by the way things were going, he did not show it to his visitors. His arrival, which had done so much to raise both civilian and military morale among royalists, did little to change the situation on the ground. The marshal was first bested in the eastern province of Oriente, moving his headquarters to central Camagüey province. After further reverses he moved it further west, to Santa Clara, where Winston and Reggie caught up with him. Worse, Máximo Gómez had crossed the great Trocha with ease at the beginning of October with a fairly large force and was now in Las Villas province marauding and tying down large numbers of Spanish troops who could not pin him down to open battle.14 The insurgent strategy was to use this force to keep the Spanish busy while Antonio Maceo was preparing an even larger expedition whose crossing of the Trocha would be assisted by the fact that Gómez’s troops were masking their movements and keeping royalist troops busy and unable to reinforce the trench line effectively. The idea was thus to effect a juncture of the two forces west of that line and proceed to the dream of all rebel leaders since the days of the Ten Years War, to take the war to the rich west and wrest the area from Spain, making it impossible for the mother country to continue to wage war.

It was the west that Churchill characterised as so wealthy in his description of why the stakes in the war were so high. Obviously impressed by what he saw in the western lands through which he had just travelled, not to mention in the prosperous capital of Havana, he wrote:

Very few people in England realise the importance of the struggle out here, or the value of the prize for which it is being fought. It is only when one travels through the island that one understands its wealth, its size, or its beauty. Four crops a year can be raised from the Cuban soil; Cuban sugar enters the market at a price which defies competition; she practically monopolises the entire manufacture of cigars; ebony and mahogany are of no account in the land, and enormous wealth lies undeveloped in the hills. If one appreciates these facts, guided by the light of current events, one cannot fail to be struck by the irony of a fate which offers so bounteously with the one hand and prohibits so harshly with the other.15

In the previous war, this dream of an invasion of the west had always proven illusory. In 1874, forces under Gómez had indeed crossed the Trocha and made it into the territory of the west-central province of Las Villas. But in the first battle in which they engaged, the hard-fought action at Las Guásimas, despite a tactical victory when the insurgents were left holding the field at the end of the day, the result was actually a strategic defeat for the rebels. The exhaustion of their precious ammunition supplies meant that they could no longer carry on with the planned ‘invasion’ of the west and were obliged to turn back.16

In 1895, however, things looked very different as the days of late November moved on. As mentioned, Cuban frustration with Spain and the lack of prospects of real reform had grown in the previous seventeen years along with the US economic connection to the detriment of the Spanish. In addition, the smoothness with which the abolition of slavery had been implemented, along with massive white immigration, was rapidly reducing white Cubans’ fears of racial strife in case of independence. Finally, the image of a great cause, expounded brilliantly by José Martí and, after May, symbolised by his martyrdom, made the former dream of independence now a goal of almost mystical value to many. Militarily, the situation was even more favourable for the insurgents. The rebellion, once its main leaders had reached the island in April, spread rapidly across Oriente and deep into the centre of the colony in ways unknown in the first war. Poor white, black and multiracial people flocked to the red, white and blue colours of a free Cuba. Equally important for the revolution’s prospects, white leaders began to appear in larger numbers than in the past. And several ‘expeditions’, those ships arriving from abroad with men and weapons, were getting through the controls the Spanish Navy was attempting to establish over Cuba’s coasts and coastal waters.

What was needed was the invasión, the centrepiece of any insurgent strategy since the beginning of the independence movement. Spain conducted both its counter-insurgency wars and also its international wars in the region with Cuban colonial treasury funds, as we have seen. Cuba was suffering from a system of taxation that sometimes beggared description, Churchill himself quickly seeing the results in what he called ‘an island which has been overtaxed in a monstrous manner for a considerable period’, adding that this meant that ‘so much money is drawn from the country ever year that industries are paralysed and development is impossible’.17 This money came essentially from the rich provinces of the west and the centre of the island, especially Havana and Matanzas. Without that revenue the Spanish war effort would suffer greatly. And without the prosperity of Cuba’s sugar industry the movement for independence would be much stronger than it was.

It was vital to do two things. First, the rebels had to take the war to the west in order to take those resources away from the imperial treasury. Second, if the great landholders who owned the sugar estates did not voluntarily agree to stop the milling of the sugar cane on which the whole economy was based, the insurrection would be obliged to apply a policy of scorched earth implying crop burning on a vast scale in the richest sugar zones to reduce further any possibility of resources coming into the Crown’s hands. This strategy, termed the tea (literally ‘the torch’), had been applied to a lesser degree in parts of the colony during the first independence war. Now Gómez was not joking. He issued a series of decrees warning the sugar mill owners that any attempt to mill would mean the destruction not only of their crops but of the buildings and machinery used to process the cane. And almost everywhere his forces went the policy was applied ruthlessly leading to vast damage to the economy and the likely ruin of hacendado and rural labourers alike. Since the western provinces produced the vast majority of Cuba’s sugar crop, with Havana and Matanzas provinces accounting for 57.5 per cent in 1894, and Las Villas a further 32.1 per cent, the threat posed was real.18

This invasion was greatly feared by the Spanish who understood very well what the rebel strategy was and that it was based on a sound analysis of the strategic situation of the day. Spanish commanders were urged to have as a priority the disruption of any moves by the rebels that would bring forward the date of the invasion, considered as the moment in which a truly major rebel force crossed the Trocha with the intention of staying on its western side. Now, as late October gave way to the first days of November, the strategic context seemed grim. Gómez was already west of the trench line with a large force of mostly cavalry tying down the Spanish. His horse-borne mobility allowed him to move at will while the cumbersome Spanish columns, almost exclusively based on infantry, plodded along attempting to catch up with him and especially to finally bring him to battle. He was having nothing of major combat which he would almost certainly not only lose but also in which he would expend his most valuable asset: his ammunition. And, as Churchill said of the Cubans in general, the combination of mobility and good intelligence, the latter available because of the essentially ‘unanimous’ support for the revolution on the part of the population, meant that ‘As long as the insurgents chose to adhere to the tactics they have adopted – and there is every reason to believe they will do so – they can neither be caught nor defeated.’19

The view of white western Cubans of the prospect of invasion is well summed up by Louis Pérez, the pre-eminent American historian of Cuba:

The Júcaro–Morón trocha represented something more than a fortified line of Spanish military defenses. In fact it gave palpable form to a boundary demarcating the eastern provinces from the rest of Cuba, fixing militarily a long standing political-cultural division between east and west. The very construct of the separatist offensive in the west, designated as the ‘invasion’ – one region of Cuba ‘invading’ another – offered dramatic expression of the deep regional distinctions existing in the minds of nineteenth-century Cubans. The west viewed the approach of eastern insurgents as nothing less than an onslaught of barbarians, threatening the very foundations of civilization in Cuba.20

It is interesting to note that this lack of friendly feelings for easterners on the part of those in the west was reciprocated by easterners, with deleterious military effects. Perez writes again that, ‘Orientales, for their part, had an equally low esteem of the west, a region they perceived as the bulwark of metropolitan authority, estranged from the historic traditions of the island over which orientales felt a peculiar custodial responsibility.’ In fact, there was considerable opposition from eastern senior officers and troops to the idea of the invasion and desertions on the way west were so frequent that Maceo had to threaten the firing squad for those who left his ranks without permission.21 In this context it was simply essential to actually conduct the invasion because only by that means could they show a dubious west that there were many whites in the Liberation Army, that its officers were mostly white, and that its troops were by no means the undisciplined hordes of black ex-slaves, hungry for vengeance against their former overlords and owners, but rather a proper army bringing with it the real prospect of national independence.

Into this situation came our two young officers, who knew precious little about Cuba, Spain, the politics behind the war or indeed the actual war into which they were thrusting themselves. For example, when Churchill wrote to his mother first laying out the plan, he mentioned his idea of arriving in Havana, ‘where all the Government troops are collecting to go up country and suppress the revolt that is still simmering on’.22 In fact, Spanish forces tended to arrive close to or directly in the zone of operations, when they came from the metropolis, often via Spain’s other Caribbean colony of Puerto Rico, to join the fight. Thus Santiago, Cienfuegos, Gibara, Nuevitas, Baracoa and any of a number of Cuban ports directly received Spanish reinforcements; in no way was Havana a collection point for them before they were to move ‘up country’. It is also of course wildly inaccurate in the second half of October to speak of the revolt as merely ‘simmering on’. It was on a fierce boil and had been for at least five months by then.

Here was Churchill, for the first time in his life, at a critical point in the history of a nation, Cuba, an empire, the Spanish, and, it can be argued, Latin America. It is scarcely credible that a coincidence of this kind could mark his young life. For at that moment exactly, as he came into the war zone, the Cuban invasion contingents, one under Gómez to the west of the Trocha and one under Maceo still to the east, were converging to effect the attack and finally invade the western provinces with the intention of decisively defeating the colonial forces and giving Cuba its independence. And two young British subalterns, one of whom would deeply affect the history of the next century and of the whole world, were there to see it and indeed to participate in the moment.

The meeting with Martínez Campos went off very well and Churchill described him as receiving them ‘affably’. The general, to say the least very busy with the long-awaited enemy invasion clearly on its way and virtually upon the Spanish, gave them what time he could. He then detailed a long-standing young member of his staff to help guide the British officers in the next stage of their journey. In another coincidence, that new Spanish officer was the eldest son of the Duke of Tetuán, the Spanish Foreign Minister from whom Drummond Wolff had obtained permission for Churchill and Barnes to go to Cuba.

Captain Juan O’Donnell y Vargas was in 1895 a 31-year-old cavalry officer, a one-time hussar, with his regiment being the Húsares de Pavia although, like Churchill, he was not to spend his whole military career in one regiment but also served for a time with a dragoon regiment, the Dragones de Lusitania. But he would certainly have felt a kinship with his fellow hussars, whichever army they came from. He was the first Spanish junior officer with whom the British officers would have had some time. A future general, third Duke of Tetuán, Grandee of Spain and minister of war in the Primo de Rivera dictatorship of the 1920s, Captain O’Donnell was at that time something of an aide-de-camp (ADC) on the staff of Martínez Campos.23

He had only been promoted to captain’s rank that March, for méritos de guerra rather than seniority, so it was through combat that he came to the notice of senior officers, who ensured a more rapid promotion than would have normally been the case. O’Donnell had served in the Army of Africa in the recent Melilla campaign, doing the job of ADC for General Martínez Campos in that war as well. But he had just arrived in Cuba from the Philippines via Spain on 7 November after combat experience in which he distinguished himself in Mindanao. The later Philippine rebellion to win independence, like the Cuban, was a second attempt, the previous one also having failed in the 1870s. But when O’Donnell was there it had not yet begun, although there was desultory fighting in the southern island much earlier than the formal outbreak of the rebellion in 1897. He had thus only been on the staff in Santa Clara for a couple of weeks when Winston and Reggie arrived but he already knew Martínez Campos very well.24

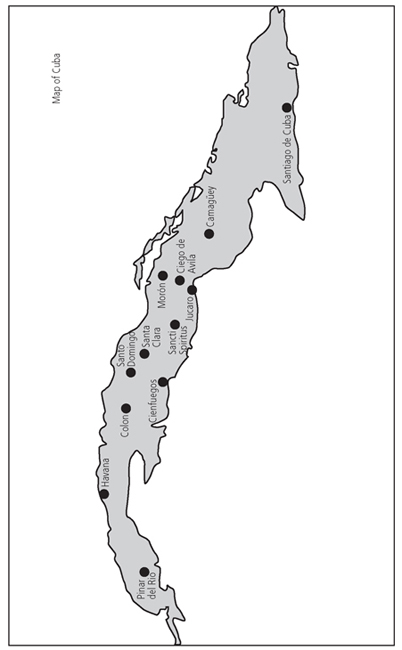

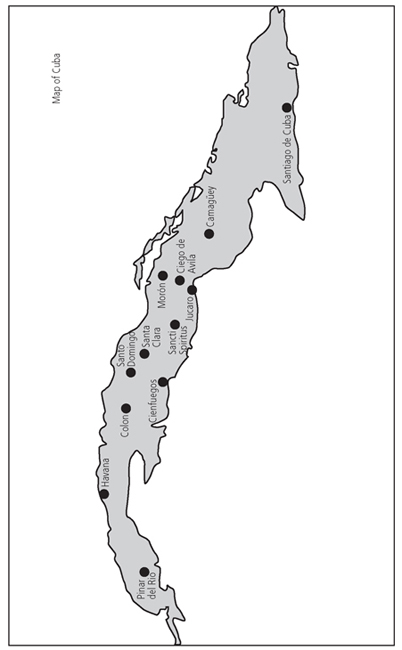

Tasked with advising the two Britons and, not surprisingly given his family background, speaking English very well, Captain O’Donnell spent some time with them and told them that the column commanded by Divisional General Suárez Valdés, the one that Martínez Campos had arranged for them to join, had left earlier that day and that they would have to meet up with it later. They asked if it would not be possible for them to ride to catch up with the general but were told by one of the other Spanish subalterns as he shook his head, ‘You would not get five miles.’ To Churchill and Barnes’ question, if this were the case, as to where the enemy were, he replied, ‘They are everywhere and nowhere. Fifty horsemen can go where they please – two cannot go anywhere.’25 This remark has been taken up by various Cuban authors to show a short but sharp description of insurgency as it was fought in Cuba in the War of Independence. O’Donnell explained that they would now have to meet up with the column in the town of Sancti Spiritus, only some 80km away but in current conditions much further because it was more complicated to get to.

Winston and Reggie would have to take a train from Santa Clara to Cienfuegos, some 80km, take ship from there to Tunas de Zaza, a sea journey of 120km, and then board another train from that coastal town inland again for the 50km trip to Sancti Spiritus. As Churchill put it in already characteristically original fashion in his next letter to The Daily Graphic, ‘Though this route forms two sides of a triangle, it is – Euclid notwithstanding – shorter than the other’.26 They set off at once so Martínez Campos was not troubled further by them as he attempted to make dispositions to stop the rebel advance. He would only meet them again two weeks later on the train back to Havana and by then in an entirely transformed strategic context.

Fortunately there was a train to the beautiful port city of Cienfuegos still available that day and they boarded it with alacrity. The trip went without incident. Churchill does not say if they were met by any military officers at the train station, whose bright colours still greet visitors to the city just as they did when Churchill and Barnes arrived that evening. Cienfuegos was a safe city for the travellers, with a large garrison, a naval base of importance and a significant force of locally recruited voluntarios. Winston sat down to write his first newspaper ‘letter’ that night.

They boarded a coastal vessel the next day, the kind that plied Cuban waters constantly and were vitally necessary for the island’s communications because of the dismal state of the roads, especially outside the richer provinces of Havana and Matanzas. This trip was again without incident and they could see the dark and brooding hills of the central Escambray Mountains chain, scene of much more guerrilla warfare in the twentieth century when both Castroist and later anti-Castro insurgents fought there, to the portside as they travelled along. They stopped briefly at the sixteenth-century town of Trinidad, now a stunning United Nations World Heritage Site, and continued on to Tunas de Zaza, which Churchill continually referred to incorrectly as ‘Tuna’. This was pretty much the true back of beyond. The sugar industry to its north ensured that the town, really a village, had a pier and some facilities but, when the officers arrived there that afternoon, they wanted only to move on by train inland just as quickly as possible. Although Churchill writes later that they were assured that military trains were getting through to Sancti Spiritus from Tunas de Zaza regularly, and the route there was strongly guarded by troops and blockhouses, this was to prove an optimistic assessment. Instead they found that the daily scheduled train had already gone but was soon to return to the port as it found en route that the line had been cut, so there was now no communication between Tunas de Zaza and Sancti Spiritus. They were thus obliged to stay the day and night in ‘the local hotel’, termed by Churchill, doubtless accurately, ‘an establishment more homely than pretentious’.27

The story gets chronologically a bit murky from this stage of the trip. It is not entirely clear when the two young men left Tunas de Zaza, and whether they stayed one night or two there. It seems from Churchill’s account that things improved the next day, 23 November, with the Spanish military and local civilian engineers repairing the damaged line and trains able to move again. This meant that the two officers were on the first one out, and moved along what was the eastern end of the Escambray Mountains, ‘which the insurgents occupy in great force’. Churchill writes that ‘the line runs close to the mountains’ and suggests ‘These thirty miles of railway are the most dangerous and disturbed in the whole island’. Yet the train got through without incident and the travellers were able to get into Sancti Spiritus station, again, according to Churchill, just before the column commanded by General Suárez Valdés marched into town after his three-day march from Santa Clara. This seems all right but contrasts with the reports to Martínez Campos made by General Suárez Valdés of his column’s progress towards Sancti Spiritus. He repeatedly referred in messages both up and down his chain of command to his arrival in that city on 24 November. This would suggest that Churchill and Barnes had two nights in Tunas de Zaza and successfully got through on that same day.28

The two Britons were not impressed with Sancti Spiritus. The pleasant colonial town of today, with its cobbled streets and lovely homes, was then nothing of the sort. It was not a small place, having at the time, according to today’s city historian, a total of about 168 cuadras or blocks and with some 1,200 stone or other solid non-wood material houses.29 But disease was everywhere. Churchill wrote of the town as ‘a forsaken place, and in a most unhealthy state. Smallpox and yellow fever are rife.’ The garrison town it had become during the war was greatly affected by its use in the campaigning close to the enormous Ciénaga de Zapata swamp, well to the south-west. Mosquitoes did their worst and the local military hospital had consequently a great many cases of yellow fever and malaria.

The officers found a hotel which Churchill described thirty-five years later as ‘a filthy, noisy, crowded tavern’ and speaks of waiting there until Suárez Valdés arrived the next evening, but in fact they stayed in the town’s best accommodation, the Fonda El Correo, on the relatively posh San Rafael Street right in the centre of town. In his second ‘letter’ to The Daily Graphic, written that night in Sancti Spiritus, he mentions that the column arrived shortly after they arrived and on the same evening.

Despite the tension he must have been feeling given the strategic situation, and with a long day’s march that day, General Suárez Valdés saw the two officers that very night. As Commander of the Sancti Spiritus District of the Spanish Army on the island, he had not just been marching at the head of his own column but had also been busy trying to get the various units, formations and columns in his district into deployments with a view to intercepting both the Máximo Gómez force already his side of the Trocha and the rebels coming rapidly westwards and even then approaching that fortified line. Communications were especially poor that week because of heavy rains, which curiously Churchill does not mention at any time.30 The most important signals link in this zone was via the heliograph stations dotted here and there around the highest hills and the most vital military posts the Spanish had. They allowed almost instant communication all the way from the Trocha itself, where the heliograph functioned from the central pivot of the line, the city of Ciego de Ávila, right back to Martínez Campos’ field headquarters in Santa Clara. However, dependent on the sun for its functioning, rain or cloud could mean the severing of this unique link and then commanders were unsure what was happening in a war without fronts where, to say the least, everything was fluid. When this happened, the only, and much less satisfactory, method to keep in touch was via the warships that dotted the coast in active support of the ground forces. These were usually small gunboats, cañoneros, built in Great Britain or the United States, and recently delivered to the Spanish Navy in Cuba. These had been the general’s main method to try to bring his various bodies of troops under effective command and coordination.

There had been no major incidents on the march from Santa Clara although some twenty rebels had briefly fired on the column on 23 November and then, following the usual insurgent pattern, dispersed. He had at least four columns out trying to find the enemy or on other duties while he marched eastwards but was obliged to ask the commander at the post at Placetas, between Santa Clara and Sancti Spiritus, to try to find out where they actually were. He also advised the Commander-in-Chief at headquarters that reports were of 2,000 insurgents operating locally.31

It was this harassed general who met the two young British officers that evening in his headquarters. Suárez Valdés was one of the most respected commanders the Spanish had on the island and it was for this reason that he was given command in Sancti Spiritus, not only a hotbed of insurgent support but also a key zone in any possible march by the rebels westward because of its location just behind the Trocha.32 The Spanish would have wished to ensure that, if the rebels were successful in getting across that line, they would be engaged immediately and pushed back across it. This would have been the general’s principal aim in such an event and the reason why he was so keen to be in touch with all the elements of his command while the strategic picture darkened for the Spanish. The propaganda effect of a successful rebel crossing would have been immense and it would have been vital to follow such possible news with others saying how it had been decisively beaten and driven back into more eastern Camagüey. The general would have been anxious to hide as much as possible of this negative context from the British officers although doubtless he also was in the dark about the fact that one of these young officers was writing for a major British newspaper and was not there as merely a visiting British Army observer.

General Álvaro Suárez Valdés y Rodríguez San Pedro was at this time a division general, usually translated as major-general. He was born in 1831 in Grado, Gijón, and considered himself an Asturian, from that northern province, home to generations of important generals and countless soldiers of the Spanish Army. He was 64 years of age at the time Churchill and Barnes visited his forces.

He had a highly distinguished career behind him although he had joined the infantry in 1857 when he was 25, rather later than was usually the case. He made up for lost time, however, and served abroad first in a then peaceful Cuba in 1860 in both Havana and Santiago, but followed this with active service in the Mexican intervention of 1861, from which he returned to the island the following year only to be posted to the Santo Domingo conflict in 1863. From there he returned sick to Havana but upon recovery was sent back into the fray on the neighbouring island. He did well and was promoted captain for méritos de guerra. In 1866 he was back in Cuba and served with the famous San Quintín regiment but before the rebellion broke out at Yara in 1868. He fought in the Carlist War of 1872 and was then posted to Puerto Rico, having been yet again promoted to the rank of comandante (major) for wartime merit. He was promoted again the very next year, to lieutenant-colonel, again for his wartime service. He was quite clearly an officer to be watched.

He was eventually called upon to go to fight in the Cuban War in 1876 when things were finally going well for the royalists. He saw much fighting as a full colonel in the Ciego de Ávila area and actually took part in a combat at La Reforma, site of the fighting wherein Churchill and Barnes were soon to experience their first action. He was to get to know most of Las Villas province at that time. The Guerra Chiquita found him still in Cuba and he took part in operations in Oriente as well over those months, returning to command jobs in the re-established peaceful island until 1886 when he finally returned to Spain for command and professorial tasks including at the War College (Escuela Superior de Guerra). Briefly during these years he was also the Governor of Santiago de Cuba.

When war broke out again in February 1895, the army sent this Cuba veteran immediately back to the island, where he arrived in the eastern port of Gibara on 17 April. Thus he had been on campaign for more than seven months when our young officers met him in Sancti Spiritus. But first he fought in the east, was decorated for his actions there, and on 25 August was called to Havana, from whence he was sent immediately to command the 5th District of Las Villas.33 He had thus been on the ground in an area he already knew well for three months when the interview with the British subalterns took place.

Churchill gives his own account of how that interview went. Once again, the Churchill sense of humour breaks through:

[Suárez Valdés] explained, through an interpreter, what an honour it was for him to have two distinguished representatives of a great and friendly Power attached to his column, and how highly he valued the moral support which this gesture of Great Britain implied. We said, back through the interpreter, that is was awfully kind of him, and that we were sure it would be awfully jolly. The interpreter worked this up into something quite good, and the General looked most pleased.34

While humorous when written a third of a century later, this was hardly a joking matter, either for British foreign policy at the time or especially for the young officers’ future careers. The general then said he was going to march on the very next day, Churchill suggesting that this was because the town was so full of disease. Much more likely, however, is that the general was not about to take the two foreign officers into his full confidence and describe to them the real strategic context the Spanish, and his columns in particular, faced at that moment, and tell them of the vital need to get moving in preparations for the rebel movements then taking place. Conversation at dinner, to which Suárez Valdés then invited them, must have been vibrant if circumscribed by the context of the moment for all three. Thus while Maceo prepared to cross the Trocha a few leagues east of Churchill and Barnes, and Gómez, while moving east to join up with him, was still harassing Spanish forces nearby, the two British officers finally found themselves in a fighting force moving to meet the enemy, for the first time in their lives.

1. Churchill, My Early Life, pp. 69–70.

2. See throughout Placer Cervera, Inglaterra y La Habana 1762.

3. See for example, Diario de la Marina, for this and next quotes, for 2 and 12 November 1895. It is true, as Lourdes Méndez Vargas argues in her look at Churchill in and around her village of Arroyo Blanco, that much of the unofficial press, or at least those less inclined to political news such as El Figaro or La Habana Elegante, did not carry the story. But the newspapers that mattered politically and militarily most certainly did. Méndez Vargas, Arroyo Blanco: la ruta cubana de Churchill, Sancti Spiritus (Cuba), Luminaria, 2014, p. 48.

4. FO 72/2013 Despatch Gollan to Lord Salisbury No. 4, dated 2 January 1895. He was not to get any in 1896 either.

5. Of the eighty Spanish generals who served in the thirty years of off–on conflict known as the independence wars, eighteen were actually Cuban-born. René González Barrios, Lecture to María Loynaz series on Cuban military history, ‘El Alto Mando español en las guerras de independencia’, February 2014.

6. This is from http://referendumparacubaya.blogspot.co.uk/2013/05, but some other non-academic sources refer to this meeting as well. Miró Argenter (Crónicas de la guerra, pp. 274–86) refers to Arderius in his often sarcastic and usually unflattering terms as an excessive worrier and ‘panic artist’, as the term goes in the army, in the later preparations for the defence of Havana against rebel attack.

7. BRDW, Winston S. Churchill, ‘Letters from the Front’, 1, The Daily Graphic, 13 December 1895. This state of affairs led to almost laughable estimates of rebel strength. The same letter refers to such estimates as ranging from 50 men to 18,000.

8. Diario del Ejército, 21 November 1895, p. 1, col. 5.

9. Churchill, My Early Life, p. 70.

10. See Gómez’s complaint to Maceo that, while he never had more than 7,000 Cubans ‘apt for service’ during that war, Spain could count on some 30,000 who ‘fought in defence of the metropolis’. Quoted in René González Barrios, El Ejército español en Cuba, 1868–1878, Havana, Verde Olivo, 2000, p. 79. By 1895 and especially as a result of the ‘invasion’ of the west, of which Churchill witnessed the beginning, this figure was never reached again and many more examples of the desertion of Cubans from the royalist forces occurred than were dreamed of in the first war.

11. Churchill, My Early Life, p. 219.

12. SHM, DIR0016 MC, Personal File, Arsenio Martínez Campos.

13. It was also rumoured that he was taking too many stimulants which, while hardly surprising given the task he had been given, cannot have helped much under the circumstances. See FO 2875 Drummond Wolff to Lord Salisbury dated 5 October from San Sebastián with the court. Martínez Campos was said to be in poor health and ‘he partakes more of stimulants than is good for him’.

14. The Trocha Júcaro–Morón was the 68km trench line stretching from the port of Morón in the north to Júcaro in the south and pivoting on the garrison town of Ciego de Ávila in western Camagüey province. It was lined with barbed wire, centred upon sixty-eight blockhouses at 1km intervals, backed up by a military railway, and had cleared fields of fire to the front for some distance to allow for easy spotting and interception of Cuban rebel forces. It was to be greatly enhanced in the years after Churchill left.

15. BRDW, Churchill, ‘Letters from the Front’, 2, 23 November 1895, The Daily Graphic, 17 December 1895.

16. The Battle of Las Guásimas is the largest battle ever to take place on Cuban soil although the 1961 defeat of the Bay of Pigs invasion is sometimes cited as more important on a number of scores. See Francisco Pérez Guzmán, La Batalla de las Guásimas, Havana, Ciencias Sociales, 1975.

17. BRDW, Churchill, ‘Letters from the Front’, 5, 14 December 1895, The Daily Graphic, 13 January 1896.

18. Quoted in Francisco Pérez Guzmán, ‘La Revolución de 95: de los alzamientos a la campaña de la invasión’, in Instituto de Historia de Cuba, Las Luchas por la Independencia Nacional, 1868–1898, Havana, Editora Política, 1996, pp. 430–80, 455.

19. BRDW, Churchill, ‘Letters from the Front’, 3, 17 November 1895, The Daily Graphic, 24 December 1895.

20. Louis Perez, Cuba between Empires 1878–1902, Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh University Press, 1983, p. 105.

21. Ibid., pp. 105–6.

22. CHAR 28/21/73 Letter WSC to Lady Randolph dated 19 October 1895.

23. It is curious that Churchill has Captain O’Donnell written down a mere lieutenant in his My Early Life, pp. 70–1, and indeed a young one at that. In fact, O’Donnell was 11 years older than Winston. His confusion, other than brought about by 35-year-old memories, may have been caused by the fact that the two British officers also met other young Spanish subalterns at the headquarters in Santa Clara.

24. AGMS/CELEB/Caja119,EXP.6 Juan O’Donnell y Vargas.

25. Churchill, My Early Life, p. 71. All later authors accepted the rank as lieutenant but it would have been very odd indeed for a general of Martínez Campos’ importance to have an ADC of such low rank and the Spanish archive reference noted in fn.109 is clear on the matter.

26. BRDW, Churchill, ‘Letters from the Front’, 1, The Daily Graphic, 13 December 1895.

27. BRDW, Churchill, ‘Letters from the Front’, 2, 23 November, The Daily Graphic, 17 December 1895. The village is sadly now in terrible shape although the pier is still there, as is a painting of it by a local artist in its former splendour of roughly the time of Churchill’s visit. The railway station, just as in Churchill’s day, is still standing, more or less.

28. It is difficult to credit that Suárez Valdés had reported incorrectly such vital dates to his commander in Santa Clara and his subordinates west of the Trocha. His wire and other correspondence in the Servicio Histórico Militar is crystal clear on the matter. See SHM Caja 3953 Campaign Operations Santa Clara November 1895, correspondence Suárez Valdés to Martínez Campos of 22, 24 and 26 November and to commanders of gunboats Cometa and Ardilla for passage to General Aldave of 22 and 26 November 1895.

29. Interview with Sancti Spiritus city historian Dra. María Antonieta Jiménez, Sancti Spiritus, 24 January 2014. Churchill’s report on disease there was certainly correct. One of the city newspapers reported 1,062 dead from smallpox and yellow fever in the city alone during the period August–December 1895. See La Fraternidad, XI, No. 512, 1 May 1896.

30. Spanish archives have repeated references to the effects of this rain, and indeed some significant storms, over the time of Churchill’s visit.

31. SMG, Caja 3953, Campaign Operations Santa Clara, November 1895, unnumbered cables Suárez Valdés to Martínez Campos of 22 and 24 November 1895.

32. Francisco Pérez Guzmán, Radiografía del Ejército Libertador, Havana, Ciencias Sociales, 2005, p. 169.

33. AGMS/1a/3437S,EXP.0. Alvaro Suárez Valdés. He was to be promoted lieutenant-general in 1896 and went on to become President of the Supreme Council for War and the Navy, and a senator. He died in 1917. See also SHM Caja 3787 Campaign Operations 1896–98 for Suárez Valdés’ actions before he joined this story.

34. Churchill, My Early Life, p. 72.