Chapter 1

Negotiation

“I'll Burn That Bridge When I Come to It”

Over the years I practiced and perfected what made sense and worked for me: You can be “a nice guy” and still get what you're after. In fact, embracing the systematic approach of this book gives you the power and allows you to get better results, achieve more of your goals, and build longer-term relationships with even greater returns.

Your First Deal

What matters in negotiation is results. Everything else is decoration. To get results you must have parties who want to make a deal, each of whom has something to gain. Never forget, everyone who sits down at a negotiating table is there for one simple reason: They want something the other side has.

You picked up this book, so you must feel you have something to gain. As authors, we have already gained by making the book sale. So, have we won and you lost? Hardly. As you'll learn, we don't want a one-time deal; we want an ongoing relationship (your recommendation of our book to others, visiting our website, attending our programs, and buying our next print or digital book). You don't want a one-time deal, either. You want to learn to negotiate every deal well. Therefore, reader and authors have a common interest (another point I'll be making later) and that is to make you a better negotiator.

To achieve that end, we each have to make a commitment. Yours is to answer two questions with complete candor (even if it hurts). Ours is to deliver on four objectives that will make you an effective negotiator.

- What negotiation have you handled recently that has not gone or is not going well? [Remember what I said about candor. Write out your answer and then show it to someone you can't fool (husband, wife, partner, friend, boss, client, mother)]

- What would you like to be able to do differently after reading this book? (Be realistic, but aim high.)

Write down your answers and save them. You're going to want to look back at them at the end of the book.

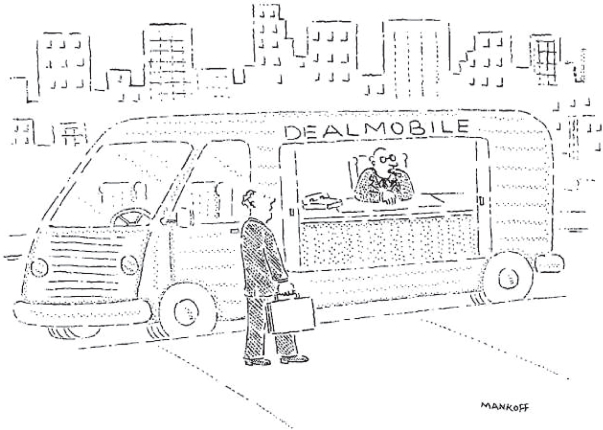

Robert Mankoff © 1988 from The New Yorker Collection. All Rights Reserved.

Four Objectives You Can Expect

- Displaying Confidence.

The most effective negotiators tend to be the most confident negotiators. Conversely, negotiators who are less confident are less effective. So, how do you get confidence and become a better negotiator? Get smart.

Lack of confidence is mostly lack of knowledge. Knowledge is power. You will be armed with the knowledge it takes to deal from strength. You won't be cocky; you'll be confident. The former is imitating someone who knows what he's doing; the latter is the person who the cocky person is imitating.

- Achieving WIN–win.

Today, everybody talks about win–win negotiation. Both sides win. Both get what they want. Both are equally happy. How delightful. How unrealistic.

If we negotiators were seeking truly equal terms and deals, like King Solomon, we'd simply divide everything in half. In reality, we're out to achieve all (or most) of our goals, to make our most desirable deal. But the best way to do so is to let the other side achieve some of their goals, to make their acceptable deal. That's WIN–win: maximize your win, but don't forget theirs.

The most common approach to dealmaking is I Win–You Lose, the pound-of-flesh school—the only good deal for me is a bad deal for you. The unfortunate fate of too many negotiations is:

We both lose

or

If I can't win, nobody can.

We'll show you how to avoid both of these negative categories.

- Using the 3 Ps.

There's an old saying, “If all you have in your toolbox is a hammer, then every problem looks like a nail.” The same holds true for negotiation. More tools enable you to solve more problems. Better tools enable you to find longer lasting, more enriching solutions. Prepare, Probe, and Propose are the first of the tools that we'll put in your negotiator's toolbox.

There is no secret formula that will enable you to get what you want every time you negotiate. But we have created a systematic approach—a step-by-step program—that, if repeated and mastered, will maximize your results. Like all good systems, this one is simple:

That's it. Close the book, you've learned it. Well, it's not quite that simple. We'll show you how to prepare better than the other side; how to probe so you know what they want and why; and how to propose without going first and revealing too much, to avoid impasses or getting backed into a corner, but still achieving what you want. As you'll see, negotiation is a process, not an event.

- Handling Tough Negotiations.

Welcome to the real world of dealmaking. Unfortunately, it's full of tough negotiators and tough negotiations. Some people think you have to be a bad guy to be a good negotiator. So, they act the part. Some aren't really so awful but have to answer to an awful boss who demands that they act the part. Sometimes, the negotiation itself may be brutal. The time, terms, or goals may be so difficult to meet that the process turns loathsome, even if the person opposite you isn't.

The tools in your negotiator's toolbox will enable you to deal with the toughest people and situations, from neutralizing animosity, to breaking deadlocks, to knowing when the best deal is no deal. You'll learn how to out-negotiate the bad guys without becoming one of them.

One more thing: If you've been around sports long enough, you know the value of a good pep talk—whether it's Herb Brooks talking to the 1980 U.S. Olympic Hockey Team—the “miracle on ice,” Gene Hackman as the coach in Hoosiers, Babe Ruth talking to a sick kid in the hospital, or Pat O'Brien invoking the memory of the Gipper (Ronald Reagan in his second-most-famous role) in Knute Rockne, All American. It can make players play harder, forget their shortcomings, and literally change the fate of the game. This pep talk isn't just about getting your adrenaline going; it's about putting PEP into learning the lessons of negotiation.

If you read this book passively, you'll be cheating yourself. If you Participate, Engage, and Personalize you'll become a better negotiator, faster. Do the exercises in the book; ask others to help you practice; role play. Don't skip over parts you find difficult or unpleasant.

No, this isn't a normal textbook approach. But that's the point. To be more effective in negotiation, you have to stop using the same old “normal” approach. To harness the Power of Nice, you have to want change, accept change, and throw yourself into that change. The results will be worth it.

What Negotiation Isn't

Think of the word “negotiation.” Quick, what images come to mind? Conflict? Confrontation? Battle? War? Or maybe: Debate? Logic? Science?

These are common interpretations that have fueled the negative approach to negotiation and are dead wrong.

Contrary to the fictionalized, Hollywood-ized, and ripped-from-the-headlines versions of larger-than-life moguls and the big-bucks business world that, up to a point, never seem to lose, from the investment bankers in Barbarians at the Gate, to Gordon Gekko in Wall Street, to Lehman Brothers in Too Big to Fail, to Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street—dealmaking shouldn't be a stare-down in a stud poker game, a shoot-out at the O.K. Corral, hand-to-hand combat, a high-tech military maneuver, or an all-out atomic war. Despite the macho, swaggering, in-your-face lingo—winner take all, out for blood, call their bluff, raise the stakes, battle-scarred, make 'em beg for mercy, first one to blink, an offer they can't refuse, nuke 'em, meltdown, go for the kill, last man standing—negotiation isn't about getting the other side to wave a flag and surrender. Negotiation is not war.

Despite all the clinical, logical, rational, psychological, data-sifting analysis, graphs, pie charts, methods, and techniques from MBAs, CPAs, CEOs, shrinks, mediators, mediums, gurus, and astrologers, negotiation is not a science.

The problem is that war stories tell well. Wars have heroes and enemies and simplistic lessons: Take no prisoners. To the victor belong the spoils. (But war, you may have noticed, can lead to more war.) And science sounds like a formula. If you do A, he'll do B, and you'll arrive at C. Maybe. Unless he does D and then what do you do?

Negotiation as war and negotiation as science have each contributed to the popularity of the negative image of dealmaking, one by perpetuating the myth that the biggest, toughest thug wins and the other by way of the equally erroneous proposition that the coldest, least human calculator prevails.

Cultural conditioning (magazines, TV, movies, best-selling books, infomercials) has reduced dealmaking to images of brutal combat—often making great entertainment on film but lousy negotiation in reality. Gordon Gekko, the classic tough-guy negotiator from the movie Wall Street, played business hardball and never seemed to lose. (This is the movies, not life.) You may recall one scene where Gekko showed an adversary how the game is played (or Hollywood's version, anyway). In the scene, the well-dressed and self-impressed Sir Larry Wildman tries to bully Gekko into selling his shares of stock cheap so Wildman can pull off a takeover deal. Gekko, of course, is too shrewd to succumb to Wildman's intimidation. Gekko's protègè, Bud Fox, watches and learns. It went something like this:

The Hollywood version of dealmaking makes good entertainment; it just doesn't make for good deals. The person on the other side of the table doesn't have to stick to the script.

Now, think of the word “negotiation” again. In order to practice the Power of Nice, start by wiping out everything you knew, thought, or felt about negotiation. Forget about winners and losers. Forget about verdicts. Forget about survivors and victims. Forget about keeping score. Forget about statistics. Forget about science. Forget about war.

Going into negotiation and counting on scientific results is like betting on the weather. If the forecast calls for a 20 percent chance of rain and you leave your umbrella home and it rains, you won't get 20 percent wet; you'll get soaked.

If you go into negotiation expecting war, bring a flak jacket. If you're armed for combat, the other side will be, too. If you have to win at all costs, so do they. Both sides attack, both sustain casualties. Neither side gives in, neither side gets what they want.

I Win–You Lose Becomes We Lose

Remember, if one party destroys the other, there's no one left to carry out the agreement. (Exacting exorbitant rents, punitive penalty clauses, or unrealistic noncompete terms often defeat their own purposes by creating disincentives; in other words, deals that are so good, they're bad.) The negotiation doesn't end when the contract is signed. If the other side is crippled by the deal, they will have every incentive to break the terms, literally having nothing to lose. You just made your first and last deal, instead of the first of many in a long-lasting relationship.

Nothing proves the point like history.

I Win–You Lose and its negative consequences seem obvious when the stakes are high and you have the historical benefit of hindsight. But the principle applies to even the simplest deal. In our seminars, we often begin with this game. You can try it yourself.

The $10 Game

Take 10 one-dollar bills. Find two people—two partners, husband and wife, people in your office, your kids. Tell them, “If you two can negotiate a deal in 30 seconds on how to divide the $10 between you, you can have the money. But there are three rules:

- You can't split it, $5 and $5.

- You can't say $7 and $3 or $6 and $4 and make a side deal to adjust the division later.

- If you don't make a deal in 30 seconds, I take all $10 back.”

Chances are, both parties will have a hard time resisting the urge to “win” and not “lose.”

You'll hear the hard sell:

- It's better for one of us to get it than neither of us so let's make it me.

- I agree: As long as the one is me.

The soft sell:

- Oh, gosh, whatever you think is fair.

- Golly, how about $7 for me and, say, $3 for you?

- No way!

The sympathy ploy:

- I need the $10. I just ran out of gas.

- At least you have a car.

The so-called logic ploy:

- We've only got 30 seconds so you take $4, I'll take $6, and we'll both come out ahead.

- Yeah, but you're more ahead.

The trust-me ploy:

- Give me all $10 and I'll make it up to you later. Trust me.

- I've got a better idea. Give it all to me, and you trust me.

- BZZZZ! Time's up!

Not only is it likely you'll keep your $10 with this game, but you can learn a lot about why negotiations don't work:

- When you have no preparation time, you don't think; you react.

- When you have time pressure and no preparation time, you revert to habits—usually bad ones. (When someone else is watching and judging your negotiations, it just adds to the pressure.)

- Most people revert to the habit of I Win–You Lose. Each one wants to win so much, is so convinced one can win only if the other loses, that they both lose.

- Sometimes I Win–You Lose turns to I Lose–You Win. “I'll take $4, you take $6.” In the quest to make a deal, any deal, people sometimes give away too much. Never forget, the goal should still be WIN–win—at least maximize and ideally, the big win is yours.”

How Can You Achieve WIN–Win in the $10 Game?

Start with this premise:

Here are some interesting solutions we've seen in the seminars:

- Look for points of agreement. Rather than leaping into battle over who gets the most money, look for an idea upon which you both can agree. For example, “If we don't make a deal in 30 seconds, we both get nothing. So, let's start by splitting $8 of the money, $4 for me and $4 for you. Now let's just negotiate over the last $2.” Once you've found one basis for agreement, you may well find more.

- Remove ego. Take subjectivity out and replace it with objectivity. Use a coin flip. “Heads, I get $6 and you get $4. Tails, you get $6 and I get $4.” Both sides now have an equal chance to “WIN” or “win.” And, regardless, it happened “fair and square.”

- Listen carefully to the rules. They're limiting but not totally restricting if you're really creative. No one said you can't make change. Split the money $4.99 and $5.01. That's only a 2-cent windfall for the supposed winner.

- Be creative—look for new approaches. Increase the pie. Again, the rules allow for imaginative solutions. No one said you can't add to the total. Let's say, you put in an extra dollar. Now you're dividing $11. You take $6 and the other side takes $5. Both sides “WIN” by increasing the pie before dividing it.

Unfortunately, most people don't reach these solutions. They fall into the conventional traps of win–lose negotiation.

The Real or the Apparent Adversary?

What most people lose sight of in dividing the money is who they're up against. Each of the two negotiators generally sees the other as the opponent. They're wrong. In reality, they're up against the person holding the money. If the two negotiators don't succeed in making a deal, the one holding the money keeps the money. Before negotiators can find solutions, they have to identify their real obstacles, not just the apparent ones.

Filling the Negotiator's Toolbox

How do you avoid the pitfalls of negotiation? Don't revert to the same old methods to solve your problems. If your only tool is a hammer, all problems look like nails; if the only tool in your negotiator's toolbox is I Win–You Lose, then everything turns into an I Win–You Lose situation. Negotiating becomes a battle of wills and/or egos. It isn't a good deal unless you defeat the other side in the process.

Conversely, if the only tool you have is I Lose–You Win, every negotiation will look like you have to give in, sacrifice, or settle for less in order to appease the other side's appetite.

Turn a mirror on yourself and ask, “What tools am I using in my negotiations?” The goal here is to put more tools in your negotiator's toolbox. By giving you the appropriate tools and an understanding of how and when to use them, you can become a more confident, and ultimately more successful, negotiator. Instead of dreading negotiation, you may even look forward to it.

What Negotiation Is

If negotiation isn't laboratory science or a bloody war, if it isn't the macho drama portrayed in the movies, what is it?

Let's take that definition apart. First, the commerce of information: Commerce is the business of trading. It's the stock market in New York, the commodities floor in Chicago, the street vendors in Tangiers. The difference here is that you're not exchanging corn futures for sowbellies or Moroccan francs for Persian rugs. You're trading what you know for what you need to know. In the negotiation market, information is the commodity. And in a negotiation, nothing is more valuable than information, whether it's two countries trying to make peace, two companies merging, two workers trading office gossip, or two kids swapping baseball cards. Is one veteran's card worth three up-and-comers? It all depends on information: What one kid wants and how bad. What the other kid has and is willing to give up.

Buzz

I'll give you a Ichiro Suzuki. What'll you give me?

Bob

I'll give you a Joe Mauer. But I won't give you my Derek Jeter.

Buzz

That's okay, my cousin's got a Derek Jeter—he'll trade me.

Bob

This one's in mint condition.

Buzz

Well, all I got is a whole mess of rookie cards.

Bob

Really? I got a rookie collection. Which ones you got?

Buzz

Let's see. I've got an Adam Jones and a Matt Wieters.

Bob

Not bad, but not enough for a mint Jeter.

Buzz

Okay, see ya.

Bob

You sure you don't have any others?

Buzz

Well, my little brother has this Mike Trout.

Bob

Too bad it's your brother's.

Buzz

He's only five and he says I can do whatever I want.

Bob

Really? Well, I have to think about it.

Buzz

I gotta go in for dinner.

Bob

Deal.

Kids swapping cards are no different from grown-up dealmakers. The commerce of information determines whether there can be a deal at all. Does one side have something of possible or real value to the other side, and vice versa? Do the sides want to make a deal or are they fishing? Is there competition? How deep are the buyer's pockets/resources? What are the terms of the deal? Who has decision-making power? Does either side have a deadline?

After feeling each other out with two players' cards either side would give up (fishing), Bob revealed he had the Derek Jeter card (possible value). Buzz wisely explained that he already could get a Jeter from his cousin (competition), which led to getting the information that Bob's Jeter card is in excellent condition (real value). Then, Buzz gave up information again, this time admitting he only had rookie cards (limited resources). Very smart move by Buzz. Either way, he learns. If Bob doesn't want rookies, there's nothing to talk about. But if he does, then there's plenty to talk about. It turns out Bob collects rookies (value for both sides). Buzz offers two rookies but Bob wants a third (terms of the deal). The third belongs to Buzz's brother, but Buzz can speak for his brother (decisionmaker). So now it's up to Bob to ponder whether it's a good deal. But Buzz has to go in for dinner (deadline).

Each side obtained information. Each side gave information. But one side got more than it gave. Each piece of information given out garnered key feedback, which better equipped that side for negotiation.

And that leads to the second half of the definition of negotiation, for ultimate gain. You enter a negotiation with a goal or goals—to get what you came for—to gain: a piece of land, a client, a lease, an option, a contract. You want to win but it doesn't mean the other side has to lose. In fact, it may not matter what the other side gains, as long as you achieve your goal. (You should even be willing to help the other side get what they want, if it enables you to realize your goal.) That's WIN–win or GAIN–gain or maximize your win.

But you're not just after gain; you want ultimate gain. That means two things. One, it may take a while. Be patient. Be ready to exchange as much information as possible. Let it sink in. Wait. Each deal has its own pace. (They can be sped up or slowed down, but not without affecting the results.) Allow each side to absorb the information, modify positions, evolve goals, adjust expectations, even save face. Ultimate gain means “ultimate” as in later, down the road, well past today's deal. It means the next deal that comes out of the first one, or a renewal of a contract, or forgiveness for late shipping, or offering a reference to your next prospect, or even making you a partner in their next deal. You never know when ultimate is coming but you can be sure it will arrive. That's when you find out just how good that deal was in the first place.

Now put the definition back together:

Negotiation is the commerce of information for ultimate gain.

Or in shorthand, negotiation is using knowledge to get what you want.

What Negotiation Can Be

Negotiation seems like a finite activity, with a beginning and an end: You're selling and I'm buying. You set a price, I offer, you counteroffer, I counter your counter, you modify, I accept, we sign, deal's done. Not necessarily.

Negotiation can be the initial step toward lasting business arrangements. It can yield clients, not just buyers. It can lead to repeat business, added business, referrals, even loyalty. Negotiation can result in partnership instead of one-upmanship. But it rarely does.

Most people act as if the deal they're making is the last one they'll ever make with the other side. In fact, the opposite is generally the case. Banks want to lend money to people who pay it back. People like to borrow from banks that give terms they can live with. Shopping centers try to retain good tenants. Tenants wish to remain where business is good. Sports teams want to hold on to their stars. Stars like to keep playing for good teams. Husbands who hate cleaning the bathtub hope their wives will trade for sweeping the garage. Most deals are just daily or monthly or yearly pieces of an overall deal…or they should be.

Name five of your negotiations that were truly one-time deals, with no ramifications, no chance for future deals, no openings for repeat business or for an ongoing relationship. Those five represent lost opportunities for long-term deals. The point is, you have nothing to lose by assuming you might do business again.

As you'll read in Chapter 4, negotiation can and should be a process, not an event. But one aspect of that idea is, when you live from sale to sale, each sale becomes a measure of success or failure. If a competitor undercuts your price, you lose. If you overpromise and can't make good, you lose. Even if you make the sale, it pays a one-time profit and you have to start over with the same customer tomorrow. When you have a relationship with a customer, prices, promises, and results are measured in total return.

Sales pay one-time profits. Relationships pay dividends. It's a simple matter of economics. Which do you prefer?

Refresher

Chapter 1: Negotiation

What it isn't, is, and can be

Four Objectives

- Display confidence. Confident negotiators negotiate better.

- Achieve WIN–win. Both parties win, but you maximize your win.

- Use the 3 Ps: Prepare, Probe, Propose.

- Handle tough negotiations.

PEP

- Participate: Be open to change, read, reread, question.

- Engage: Throw yourself into the process of learning negotiation.

- Personalize: Relate what you learn to your career and your life.

Lessons from the $10 Game

- Find ways to agree—create momentum.

- Remove ego—break deadlocks.

- Listen carefully to the rules.

- Be creative—look for new approaches. Increase the pie—before splitting it.

Negotiation is not war.

Negotiation is not a science.

Negotiation is the commerce of information for ultimate gain.

P.S. Don't negotiate with kids. Chances are, you'll lose.

Kevin KAL Kallaugher, Kaltoons.com.