Chapter 2

I Win–You Lose Negotiation—An Exercise in Flawed Logic

Enemies and Entrenched Positions

I Win–You Lose is probably the most common (and least productive) approach to negotiation. Victory, not the achievement of goals, is the only acceptable outcome. And the counterpart of victory is defeat. In order for one side to gain what it wants, the other side must give up what it wants. There is no winner unless there's a loser. This is negotiation as war. The other side is the enemy. The success rate is about as good as that of war—seldom and rarely long-lasting—the opposite of the Power of Nice.

Enemies

In I Win–You Lose negotiation, one side assumes the other is an adversary. Sometimes both sides assume so. They couldn't possibly each be business people or neighbors or siblings or even fellow human beings. They couldn't share wants or needs or fears or hopes. They have nothing in common. They're enemies.

And as enemies, there's no goodwill, no open-mindedness, no willingness to learn about each other's pressures, priorities, and goals in the negotiation. There is no trust.

If you subscribe to that outlook, there is no opportunity for mutual interests, creative solutions, and, least of all, building a relationship:

- The two parties may never learn that one party could have a delayed payout for tax purposes and the other party can meet a high price only if allowed to pay over time. Or that both sides must get the deal done by the end of the calendar year. Or that a third player has been talking to both.

- They may never experiment with shared profits instead of fixed payments. Or open books on both sides. Or lending each other talented employees. Or forming an alliance instead of trying to drive each other into oblivion.

- And they will certainly never explore how this deal might lead to others. Or joining forces instead of one buying out the other. Or one giving the other a “first look” or “second chance” on the next opportunity.

They are not at the table to reach their goals; they're at the table to defeat the enemy. And the assumption (usually erroneous) is that they will never encounter this same “enemy” again. They conveniently forget the cliché, “It's a small world,” which got to be a cliché because it's true.

Entrenched Positions

If you believe there's no victory unless there's defeat, if you assume the other side is your enemy, then the negotiation process itself is nothing but taking a position, stating it, and restating it (sometimes louder for emphasis):

- “My price is $1,000,000.”

- “Is there any room for negotiating… ?”

- “My price is $1,000,000.”

- “We don't have that much but…”

- “Too bad. We'll have to go to your competitor.”

- “If we could have some time…”

- “The offer ends at midnight.”

- “Maybe we could…”

- “My price is $1,000,000.”

I Win–You Lose negotiators don't determine the individual circumstances, needs, or particular interests of the other party. They simply arrive at their offer or their price or their terms or all of the above. They often take it or leave it. (Their idea of an offer.) And, by the way, there's a deadline. (Their idea of an incentive.)

The one thing they don't do is listen. There's a cynical expression that describes the entrenched approach of the win–lose negotiator perfectly: Don't confuse me with the facts. Why learn when I've already made up my mind? Why compromise? Why meet halfway? Why try give-and-take? Why look for common ground? Why find an innovative answer, creative terms, or a new route? You're the enemy. You're only trying to get the better of me. (After all, that's what I'm trying to do to you.)

Entrenched negotiators have a great deal of trouble completing deals. It's no wonder. They have so fixed their position, they have nowhere to move. Only a perfect coincidental match will work. You must need exactly what they have to offer, at the price they're offering, on the terms they're offering.

Meanwhile, deals are being made all around them and they wonder why.

Hit and Run

Don't Win–Lose negotiators ever make deals? Sure, it happens. In fact, there isn't a seminar we do where someone doesn't come up and say, “Hey, I know somebody who fits that win–lose description and I've seen them make great deals.” Okay, it's true. How and why? When the quick-hit, I Win–You Lose negotiator is in an advantageous dealmaking position (i.e., desirable property, best talent, available space, an attractive client list, ready cash, an anxious buyer), he or she tends to opt for Instant Deal Gratification—get it all and get it now. Take cash, not an earn-out. If you get a higher offer, take it. Promises are nice, cash is better. How can they do it? They're Hit-and-Run negotiators. They get in, score, and get out, scoring one-time deals that make a fast buck and have a short life. No long-term relationships and very little repeat business.

But when their transactions are examined closely and over time, their apparent grand successes are often matched with equally grand failures. The sports agency business seems to have more than its share of Hit-and-Run negotiators. They're the agents who make headlines by bad-mouthing ball clubs, constantly making their players holdouts, and shamelessly shopping their players to get one-time, record-breaking contracts rather than life-fulfilling, career-making deals. They love to “leak” their big-dollar deals and their own prowess to the press.

What the Hit-and-Run negotiators don't like to mention, though, are the numerous times their strategies cost their clients money over the long term, waste years of a player's potential professional development or, worse, threaten or end a client's career.

I've Never Been on the Cover of Sports Illustrated

A case in point is the fame, or infamy to some, of NFL agent Drew Rosenhaus. He has represented prominent football players, from wide receiver Terrell Owens to tight end Rob Gronkowski to cornerback Jimmy Smith. There's probably no football agent (with the possible exception of the fictional Jerry McGuire) better known than Rosenhaus. There is no question that Rosenhaus is an adept promoter. The question frequently is: who is he promoting most, his players or himself? Rosenhaus is a nonstop Tweeter, a ubiquitous sports–talk show guest, and, in the ultimate irony (or professional courtesy?) he once actually wrestled a real shark in the water. In 2011, 60 Minutes featured Rosenhaus. During the piece, CBS's Scott Pelley described Rosenhaus as “an agent who is at the same time revered, feared, and hated.”

Rosenhaus is no stranger to headlines. The classic 1996 Sports Illustrated cover headline shouted, “The most hated man in pro football” next to a color shot of Drew Rosenhaus and his own words, “I am a ruthless warrior. I am a hit man. I will move in for the kill and use everything within my power to succeed for my clients.”

Inside, the article described Rosenhaus's negotiation style. “Deceit is part of his job. He will not only lie, he will also scream, cajole, threaten, and whine to defend his clients' interests… He has been described as slithering and blindly ambitious.” The story quotes other agents on Rosenhaus, “When you look up sleazeball agent in the dictionary, there's a picture of Drew,” are the words of Craig Fenech and, according to Peter Schaffer, “Drew is the biggest scumbag in the business.”

Pretty strong words: He may even sound effective with all that hype. But bloody victories that leave a trail of carnage do not necessarily make a successful negotiator. The ability to make deals and build relationships that lead to more deals is the definition of an effective negotiator. Will the Drew Rosenhaus clones, who have one-shot, headline-making wins, continue to have them, one after another, in the long run? Maybe.

But after reading the Sports Illustrated article, I said to myself with respect to Rosenhaus, “Give it some time and there'll be stories about how the Win–Lose approach blew up in his and his clients' faces.”

Readers didn't have to wait long. The reports came fast and frequently. First there was USA Today columnist Bryan Burwell's piece on Errict Rhett, a well-known Rosenhaus client, headed, “Rhett's holdout turns out to be big bucks mistake.” This is how Burwell described the situation:*

Rosenhaus lost a client. Rhett lost millions of dollars, his starting position, and possibly damaged his career irreparably.

As for Rosenhaus himself, his style has kept his career in high profile. Whether that has always been what's best for his clients is a matter of opinion.

Hit-and-Run negotiators tend to leave victims in their wake, that is, customers, clients, investors, buyers, and sellers who've ended up on the lousy end (temporarily) of the Hit-and-Runner's abusive, shortsighted strategy. Rather than negotiators, they're opportunists. There's nothing wrong with opportunity. When it knocks, you should answer. But if that's all you do, you may miss out on the bigger rewards of deals that last years, renew, and lead to other deals (as well as the intangible benefits of long-term relationships).

I'm Not One of Them, Am I?

Okay, readers, right now you're saying, “I don't have to worry about being a Win–Lose negotiator. I never beat up on the other side. I don't need to read this book. Everyone I negotiate with needs to read it.”

None of us likes to think of ourselves as Win–Lose negotiators, but there are times when we give in to the temptation of the moment, when we hold the cards, or want to get (just a little bit) even with the other side, and we give in to the dark side and go for the kill.

We've all been there. Truth be told, we all speak from experience. There are four situations that arise when even the most dedicated WIN–win negotiators may be tempted to cross over to Win–Lose:

- When you've been hit (hurt, damaged, taken advantage of) and have the urge to hit back.

- When you allow principle (I'm going to teach them a lesson) to cloud vision or become a rationalization.

- When you think you have the upper hand and underestimate the other side.

- When you oversell, driven by the desire to make a deal rather than to make the right deal.

The stories that follow are each examples of giving in to the temptation of Win–Lose negotiation and the negative outcomes that inevitably result. The first illustrates that even though I've tried to take a WIN–win approach throughout my career, I, too, have fallen victim to the lure of Win–Lose.

What are the lessons of the strike? Everything that could be done wrong was done wrong.

- Each side perceived it had the upper hand and underestimated the other side. Each side was determined to make the other side back down. All the other “wrongs” stemmed from that premise.

- What should have and could have been handled with delicacy, privacy, and confidentiality, was allowed to deteriorate into the worst sins of Win–Lose negotiation. There's no victory without defeat. My gain is your pain.

- It was a negotiation between enemies. Royalty and Peasants. Labor and Management. North and South.

- It was a battle of entrenched positions. Over the course of the entire year, neither side materially modified nor compromised its stance. Every meeting was an echo of the last. Repetition replaced innovation.

- Despite how long it took, it was a hit-and-run deal. Baseball finally resumed on a delayed basis in 1995. But it wasn't the result of negotiation; rather, it was by virtue of a judge's ruling (and it's worth noting for the historical records that the judge was future Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor). Unfortunately, it was a short-term solution; though the strike had ended, the issues remained.

- The parties' differences were not resolved. Both parties walked away dissatisfied. The distrust did not abate, it festered.

- I Win–You Lose turned to We Lose. The players and owners both dealt from I Win–You Lose postures. Who won? Nobody. Who lost? Everybody: including baseball's constituency—the media partners, the advertisers, and the fans. For a long time to come, they were all skeptical and they were vulnerable to other suitors—football, hockey, basketball, golf, or any form of entertainment that captured their fancy and didn't let them down. The great American pastime struck out.

Of course, eventually, Major League Baseball did learn its lesson, but far later than it should have.

At Least One Dissatisfied Party

In an I Win–You Lose negotiation, one thing you can count on is that somebody will walk away unhappy. The approach practically demands it. If the winner really wins what he or she set out to win, then it was at the expense of the loser. The loser goes home with nothing, except maybe a long memory. If these two ever sit down again, you can bet the loser will be out for more than a deal. The loser will want revenge: Wait until it's my turn to be the tough guy.

Because of the nature of I Win–You Lose negotiation, its adversarial, non-accommodating approach, the impasses it creates, there's a good chance that at least one party will not only walk away without the deal they sought, but will come away with practically nothing.

Refresher

Chapter 2: I Win–You Lose Negotiation

I Win–You Lose Negotiators

- Treat each other as enemies.

- Stake out entrenched positions.

- Adopt hit-and-run philosophy.

Win–Lose Negotiators

- Leave a trail of victims.

- Miss out on deals that last, renew, and lead to more deals.

- Lose the intangible benefits of long-term relationships.

Even if You Mean to Be WIN–win, You May Give in to the Temptation of Win–Lose When

- You've been hit and have the urge to hit back. (Oprah)

- You allow “principle” to cloud vision. (The Circus and the Arena)

- You think you have the upper hand and underestimate the other side. (The Baseball Strike)

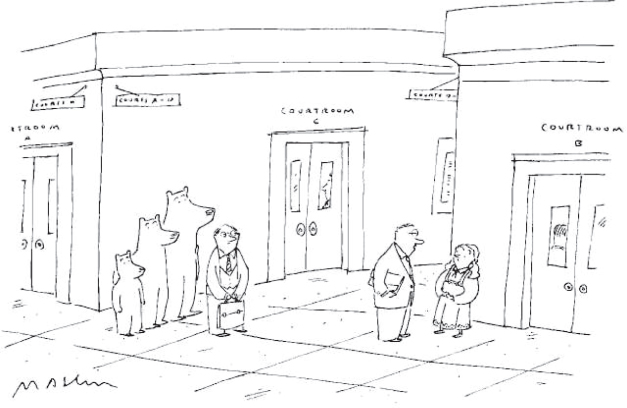

“They're offering a deal—you pay court costs and damages, they drop charges of breaking and entering.”

Michael Maslin © 1988 from The New Yorker Collection. All Rights Reserved.