Chapter 3

WIN–win Negotiation

Myth and Reality

The Myth of Win–Win

Negotiation experts (and amateurs) have been preaching win–win for some time. The trouble is, it's unrealistic. The expression win–win has become more of a pop cliché than a negotiating philosophy. It's either a winner's rationalization for lopsided triumph, a loser's excuse for surrender, or both sides' phrase for when everybody is equally unhappy. There's rarely such thing as both parties winning identically, that is, both getting all of what they want. One party is bound to get more and one less, even if both sides are content with the outcome. The latter is possible. Both parties can be satisfied, but both do not usually win to the same degree.

The Reality of WIN–win

If someone is going to come out ahead, it would be great if it's you, but at the very least you maximize your interests.

For example, in the $10 bill game in Chapter 1, rather than quickly retreat to a division of $4 for you and $6 for them, one way to maximize your return is by making change, a split of $5.01 and $4.99. Even if you end up with the $4.99, you have substantially increased your return over the $4 split.

WIN–win is realistic. It isn't easy—it requires focus and discipline but it is achievable. And it doesn't turn negotiation into war. Because it's not WIN–lose, WIN–clobber, or WIN–ransack-pillage-and-obliterate, you don't have to destroy the other side. On the contrary, you want them to survive, even thrive, in order to make sure the deal lasts and leads to future, mutually beneficial deals. That's the Power of Nice and WIN–win is what that power delivers.

Achieving WIN–win

Know What You (Really) Want–Know What They (Really) Want

To achieve WIN–win, the first order of business is to identify your own interests and goals, what you really need to achieve from a potential deal. You may say, “Hey, I do that automatically.” But that's the problem. What you automatically assume to be your goal may not be what you really require to make the deal worthwhile. For example, you may assume you must get a certain price for a piece of real estate. Do you make the assumption because you hear that's the current market value? Or because another seller supposedly got that price? Or because you promised your partners a given return? Is your price really engraved in stone? Will you take less if it's a cash offer but insist on more if paid out over time? How about the emotional aspects of the deal? Are you trying to get out from under a burdensome property? Are you saddled with nervous investors? Perhaps you need peace of mind more than money. Or vice versa.

You can't satisfy your interests until you know what they are. And they're rarely as obvious—or simplistic—as you might assume. But, if you force yourself to think through your priorities, your interests will clarify. You will learn the true parameters of your needs, what you can sacrifice, and what you can't.

Before you go into a negotiation, ask yourself what you want out of it. Then challenge your own answers. Take apart your demands. Make hypothetical offers to yourself, each with different terms. Rank your needs. Force yourself to give up goals from the bottom of the list up, until you're left with the one most important goal of the deal. Now you know what you want.

But you're only halfway there. You have to do the same for the other side. Try to determine their needs and interests. Just as you can make the mistake of assuming your goals, you could make the mistake of assuming theirs: You want to get as high a price as possible so they must want to pay as low a price as possible. What if you learned that they might pay substantially more if you let them push the deal into their next fiscal year? Or that while you have investors clamoring for a return, they have shareholders who are in an acquisitive mode? Or that while your constituents want land, they want security?

Determining someone else's needs isn't easy to do alone. Get someone to play the Devil's Advocate, thinking on behalf of the other side. By role-playing, the advocate will look out for and reveal to you real interests of the other side, instead of your having to rely on your assumptions. Or, if you have the opportunity, directly probe the other side for its interests.

Chances are, their interests are as complex as yours. The earlier you know what their interests are, the greater your leverage will be. Some of their goals may become apparent as you negotiate. But that may be too late to react or counter.

The chapter that follows this one deals with the 3 Ps, one of which is prepare. It means, among other things, learn all you can about the people with whom you're negotiating, what motivates them, and, importantly, what they must achieve in a given deal. Find out as much of what they need as you can before you sit down at the bargaining table. You will discover even more once you're at the bargaining table, during the probe phase, which follows prepare.

Satisfy Your Interests Well–Satisfy the Other Side's Interests Acceptably

Once you know what the other side needs, you can determine how their interests conflict and/or mesh with yours. You can find areas of mutual benefit: your price and their terms; their divestiture and your expansion; their capital needs and your investment strategy.

You each have strengths and weaknesses. But, if you do your homework, (and if you probe effectively) you have an advantage. You know what you want and you know what they want. You may be tempted to fulfill all of your own needs and to disregard theirs. Believe it or not, that's not in your best interest. No matter now much stronger your position may be, make sure they achieve some of their goals. That's what enables a deal not just to be made, but carried out.

Let's say you're negotiating with three suppliers for a season's worth of embroidered NBA logos for hats—in round numbers say 24 million logos. Your goal is to lower the cost by .017 cents per logo, but to maintain the quality of those little woven Bulls, Heat, Knicks, Spurs, Thunder, Cavaliers, and Magic. (Ideally, you'd like this season's 24 million hats in your warehouse by tip-off of the first game.) You've had multiple logo suppliers in the past but now you're willing to give the entire 24-million-logos order to one company if they can meet your specs.

The first supplier, Econo-Emblems, comes in with the lowest price, but only on the condition that they can sew logos with a slightly lower thread count per centimeter. The second supplier, Logo-Motion, can meet the thread-count quality standards but at a cost of .003 cents more per logo, which really adds up when you multiply it by 24 million. The third supplier, Sew-What Ltd., meets the lowest price and the thread count but they ask for staggered delivery dates. They'll deliver 8 million logos a month, feeding fan demand as the season goes on. You could reject their request for staggered delivery. And they might give in. After all, this is the biggest order in the industry.

But you know their needs, their real interests. By staggering the delivery dates to you, they'll fill factory capacity over several months, eliminating downtime, keeping the best workers employed throughout the year, thereby increasing profits on other, previously unprofitable jobs, all of which enables them to give you both the price and quality you want. If you force them to meet the original schedule, you run the risk of sacrificed quality to make the dates or missed dates to maintain quality. And even if they make the dates and maintain the quality, their overall operation will likely lose money and never be able to meet the same specs again.

Remember the one goal at the top of your list. Lower the price without sacrificing standards. You WIN, in capital letters. Now let them win on the delivery schedule. Their win assures your WIN. It enables them to carry out the agreement. Instead of what might be, at best, a one-time, one-sided win, or, at worst, a one-time disaster, you now have the makings of a long-term relationship. Remember, the essence of negotiation is not just making a good deal; it's building relationships.

Good Deals Echo, They Lead to More Deals

Often, the best way to get what you want is to help the other side get what they want. There are very few deals in business or life, in general, that are truly one-time, never-again transactions. The world of negotiation is a small one. How often have you:

- Done business again with someone with whom you did business what seems like a lifetime ago?

- Awarded a job to a supplier who was the runner-up last time you bid them?

- Discovered a familiar name as a reference on a resume?

- Called on an old acquaintance for an opinion?

- Hired a competitor?

- Invested in a rival?

- Found yourself a seller to the same party to whom you were once a buyer?

Too many people negotiate as if they'll never again see or do business with the person across the table. That was the modus operandi of my ex–law partner, the bridge-burner. In fact, the opposite is true. Chances are, you will associate and do business with the same people again. More leases are renewed than written from scratch. More suppliers are retained than replaced. More contracts are extended than begun. More shipments go to old customers than new ones. There's an old business adage that says it takes five times the time/effort/money to win a new client as it does to keep an existing one. The same, with varied multiples, applies to anyone on the other side of a transaction.

If you treated your last deal as your final deal with that party and left them with a bad taste, or worse, bad business results, next time they'll either come to the table with revenge on their minds or not come at all. But, if you did your best to make sure they got some of what they wanted, if you made sure they achieved a win (lowercase), you have the potential of making mutually beneficial deals ad infinitum.

WIN–win Is Not Wimp–Wimp

We've established that WIN–win is not win–win. It's clearly, unashamedly designed to maximize your return or even tilt the scale in your favor. It's not pretending that both sides go away with separate but equal smiles. But, importantly, it also stands in sharp contrast to win–win's mutated relative, Wimp–Wimp. That's where you want to make a deal so badly, you make a bad deal. You give in, give up, and give away; anything to get the deal done.

We've identified five notorious Wimp–Wimp negotiator types. Here's how each would negotiate the purchase of an automobile:

Wimp–Wimp Negotiators: Buying a Car

- Addicted Wimp. The addicted negotiator walks into the dealership, falls in love with the red sports utility vehicle, and decides he or she wants it and wants it now. Addicted negotiators don't really care about the terms of the deal, the financing, the extras, or even the undercoating. They will concede all of it and pay full list price, as long as they can drive it home today. These negotiators want to do a deal, any deal, so badly that they make unnecessary and harmful concessions just to get the deal done.

- Anxious Wimp. The anxious negotiator walks into the dealership and thinks, “I hate doing this. All these salespeople know how to play the game, and I always lose. I don't want to look bad. I don't want to look stupid. I just want to get this thing over with as quickly as possible. Next time I'm going to CarMax so I can avoid this whole negotiation thing.” These negotiators will accept the first offer put onto the table just so they can get the process over with.

- Apathetic Wimp. Apathetic negotiators think that negotiating is not worth the hassle. They know they could get a better deal, but they also know it means shopping around to different dealerships, reading Consumer Reports, and even going back to the same dealer several times to work the price down. They know they could get a better price using this strategy, but they just don't want to put in the time or the energy to make it happen. This negotiator justifies that the time and energy saved in not negotiating makes up for the higher price they inevitably pay.

- Aristocratic Wimp. The aristocratic negotiator walks into the dealership, refuses to speak with any of the salespeople, and demands to see the manager. He or she tells the manager he or she is going to spend top dollar and does not want to get into a haggling scene over the price. “Just give me a price and I will tell you whether or not I will buy the car.” Aristocratic negotiators rationalize that negotiation makes them feel “cheap” and, therefore, they claim to be “above petty haggling.” They do not want to engage in the game of negotiation and often leave plenty of lost money on the table.

- Amiable Wimp. The amiable type walks in and immediately gets into a long conversation with the salesperson about their families. Before you know it, the amiable person knows everything about the life history of the salesperson, including the fact that he or she is one car away from getting that bonus that will help to pay for Junior's braces. In the end, the amiable person just takes the deal that is offered because he knows that it will help the salesperson out and really feels that he and the salesperson can become good friends—and he would not want to negotiate with a friend. In the end, it is more important to be liked than to get the best deal. And Amiable Wimpiness isn't just a buyer's trait. It can just as easily be the salesperson who gives in by reducing the price before any negotiation even begins, just to make the sale and to be nice to the customer who is now his or her friend.

Regardless of variety, the Wimp Negotiator becomes a Wimp in the quest for a deal. This isn't disastrous if the other side is also a Wimp. The real danger is when you become a Wimp and the other side doesn't. Then you become something worse than a Wimp; you become a Loser. The process turns to Lose–Win.

We had a participant in our seminar—a broker with a prominent national investment firm who specialized in retirement plans. He confessed that he knew he suffered from a Wimp–Wimp approach but found it almost impossible to unlearn. His story illustrates the old maxim, “Old habits are hard to break.”

Roadblocks, Minefields, and Wisdom

Okay, it's simple, right?

- Know what you want. Assess your needs and wants before negotiating.

- Find out what they want—probe, dig, ask, learn.

- Satisfy your interests well.

- Satisfy their interests acceptably.

What could go wrong? Nothing: If the path to a WIN–win deal was a straight shot. But it isn't. It's almost always littered with barriers, hurdles, detours, potholes, hazards, and all manner of obstacles to keep you from getting to where you want to go. Here's what they look like.

Insufficient Planning

When we harp on the need to prepare, it applies to both sides, yours and the other party. Unfortunately, we can only influence your side. The more prepared you are—the more you know about your goals and their goals, your absolutes and theirs, flexibilities, time limits, creative alternatives, pressures—the greater the opportunity to make a good deal.

As for the other side, the less prepared they are, the more difficult it may be for you to make a deal. The process will surely go slower. They're likely to be skeptical of even the most reasonable offer. Unlike you, they have not thought through various scenarios in advance. They're worried about what they don't know, even paranoid, and therefore less willing to compromise. They may obsess on issues of contention (whether they're meaningful or not) instead of focusing on the bigger issues (on which you could be in agreement).

Why would people not prepare? It's natural. Planning is not fun. Doing is fun. Planning is tedious. (Even if it makes the doing better.) Vacations are fun. Packing isn't. Arriving without socks is not fun. Eating is fun. Flossing isn't fun. Root canals are as unfun as it gets. Spending is fun. Saving isn't. Bankruptcy is only fun if you're a bankruptcy lawyer.

Ineffective Communication

Many negotiators think they're outstanding communicators because they're good talkers. They have big vocabularies, are never at a loss for words, always have a snappy comeback. The problem is, most negotiators aren't good listeners.

When they talk, they're saying what they want to say, instead of answering the concerns and needs of the other party. They're not communicating their ideas clearly; they're uttering words they want to hear themselves say. Or worse yet, the communication takes place through legal representatives and documents, rather than face to face, human to human.

Often, if the other side doesn't communicate effectively, they don't listen well either. They may listen through a negative filter. They suspect what is being said; they're skeptical of motives. It can't be good; it's someone trying to get the better of them. In the end, both parties end up in disagreement, not necessarily over issues, but over the manner in which the issues and positions were expressed.

In the chapter on probing we'll talk about Listening. We'll show you that listening is more than waiting to speak. It's an art and a science. You can practice it and get better. Listening may be the single most powerful tool in achieving WIN–win because it can inform you what the other side really wants and needs to make the deal.

Inexperience

It seems like too many negotiators' jobs are filled by the following help wanted ad: “No experience necessary,” because too many perfectly good deals go bad simply as a result of inexperienced negotiators.

Novice negotiators just haven't made enough deals to know what matters and what doesn't. In their quest to avoid a bad deal, they often avoid making a deal at all. They sometimes take a hard line when it isn't necessary. They offend the other party either accidentally or because someone told them that negotiators are supposed to be tough guys. They believe, out of naiveté, in win–lose negotiation. If they can't win, they'd rather walk away. They react emotionally instead of rationally: all of which can be the undoing of an otherwise promising deal.

The experienced negotiator should know how to handle an inexperienced counterpart. Don't take it personally (no matter how offensive). Don't get hung up on tactics (no matter how crude). Do exercise patience. Let the novices make mistakes, say the wrong thing, back themselves into corners, rant, rave, and demand. While they're ranting, you're thinking. When they're demanding; you're strategizing. They are actually giving you time to calmly assess (or reassess) your position, your method, and your priorities.

Putting It Together

When you can put all the elements together, get past positions, when you can identify what you really want, what the other party really wants, when you can satisfy your interests well and the other side's interests acceptably, that's when you can make a WIN–win deal. Here's a case in point:

It doesn't usually take 11 months to get past the impasses. In this case, it was definitely worth it. The dollars and the length of the deal made that clear. However, in most deals that's not necessarily the case. Determining how much time is warranted is important…but not easy to assess. Many people, particularly salespeople, don't look closely enough at the time they spend on a deal, sale, or challenge to see if they are spending it wisely.

WIN–win and maximizing your interests means not just the size of the deal, the profits, or other benefits, but also the time you invest to make the deal—literally the ROI on your efforts. You must ask yourself, “Does what I'm doing make sense?”

To help you answer that question objectively, we've created the Value/Pay Grid.

First, let's define Value. This is the regard your customers hold for your product or service compared to other options in the marketplace—average, good, better, best. And how they regard you as their representative. As for Pay, that's just what it says, how much your product or service is worth compared to other alternatives—the same, less, or even a premium. And “pay” is not only dollars; it can be in the form of other gain, need, or benefit.

Let me give you some examples for each of the boxes in the grid. In the upper right quadrant, Value/Pay, people or customers who fall in this quadrant might say, “I love what your product offers us. I'm confident it's the right product for us. I love you as our sales rep and that you make sure we are always taken care of. Keep doing what you're doing and we'll have a long and productive relationship.”

Those in the lower left quadrant, No Value/No Pay are the exact opposite and will say so, “I don't care about your product or what it has to offer us. I don't particularly care for you as a sales rep and have no interest in working with you or your company.”

Those two quadrants are easy to identify. The other two are where the challenges come.

In the lower right quadrant, No Value/Pay, customers may say, “I don't care about your product or what it offers us, nor do I particularly care for you as a sales rep. However, my boss says we need the product, or thinks highly of you, so I'm required to work with you. Just understand, the moment it's up to me, I will stop buying.”

In the last quadrant, Value/No Pay, customers sound like this, “I love what your product offers us. And I love you as our sales rep and that you always make sure we're taken care of. But…I just don't have the budget to give you any business. So, keep doing what you're doing and one day I'm sure we'll do business together.”

Now, before you decide how to deal with each customer or quadrant, first go back to that ROI question, “Does what I'm doing make sense?”

- Value/Pay—They love you and/or your company. Keep doing what you're doing. The key is to not forget about them and their loyalty. Sometimes we take good customers for granted. As time goes by, these customers can start to resent the lack of attention. They value you. You must value them.

- No Value/No Pay—Even though they don't value your product or your personal service, it's good to know where they stand. After some effort, if you can't accomplish the goal of demonstrating value of your product, you may decide to spend less time and resources on them.

- No Value/Pay—Some people will look at this quadrant and think it's terrible, or certainly tenuous business. But while you prefer customers who appreciate your product and dedication, this is not entirely bad business to have…if it's priced and serviced correctly. You may wish to move them into the Value/Pay quadrant, but if you can't, and if you realize they may leave at the first opportunity, in the meantime, you can have a profitable, realistic relationship.

- Value/No Pay—This is the worst quadrant of all. That may surprise some but when you think about it critically, these are the time- and resource-suckers. They tell us how much they value what we do, but they can't work with us right now, or can't pay enough. They ask for research, proposals, ideas, free consulting, and we keep giving it all to them in hopes that someday we might get some business. But in the meantime, they're chewing up valuable time. You have to either move them into the Value/Pay quadrant…or into the No Value/No Pay quadrant, and then move on to spend your time more wisely.

Many people won't fall unquestionably into the middle of a particular box. They may be a little bit of one, leaning toward another, or straddling a line. But eventually it should become clear where they fall. Your job is to analyze each of those relationships as objectively as possible. Ask yourself, “Does what I'm doing with them make sense?”

Sometimes Maximizing Your Win even means walking away. It may be the best use of your time, the highest ROI on your time investment. (See Chapter 10: No Deal.) You and your company's time, resources, information, and people have value. If you don't believe that, no one else will either.

Here's a real-life story of how the Value/Pay grid can work.

Refresher

Chapter 3: WIN–win Negotiation

- Myth of win–win: Both parties may benefit, but there's rarely such a thing as truly equal deals or wins.

- Reality of WIN–win: If someone is going to come out ahead, it would be great if it's you, but at the very least, you maximize your interests.

Achieving WIN–win

- Know what you want. Assess your needs and wants before negotiating.

- Know what they want. Find out—probe, dig, ask, learn.

- Satisfy your interests well.

- Satisfy theirs acceptably.

Good deals echo—they lead to more deals.

WIN–win Is Not Wimp–Wimp

- Don't turn into a negotiating wimp.

- Don't lose in order to win.

- Don't give in just to get the order.

Five Wimp–Wimp Types

- Addicted—anything to make the deal.

- Anxious—accepts the deal to get it over with.

- Apathetic—time saved is worth overpaying.

- Aristocratic—negotiating is beneath them.

- Amiable—more important to be liked than to get a good deal.

Roadblocks to WIN–win

- Insufficient planning: Someone isn't ready or prepared to negotiate.

- Ineffective communication: Someone isn't listening.

- Inexperience: The novice is negotiating the way they do it in war or in the movies. That makes the process hard for both sides.

Maximize your Time and Resources Using the Value/Pay Grid

- Don't waste your time in the Value/No Pay quadrant.

- Analyze your relationships as objectively as possible. Ask yourself, “Does what I'm doing with them make sense?”

- Sometimes maximizing your Win requires you to “walk away” or reallocate your time.

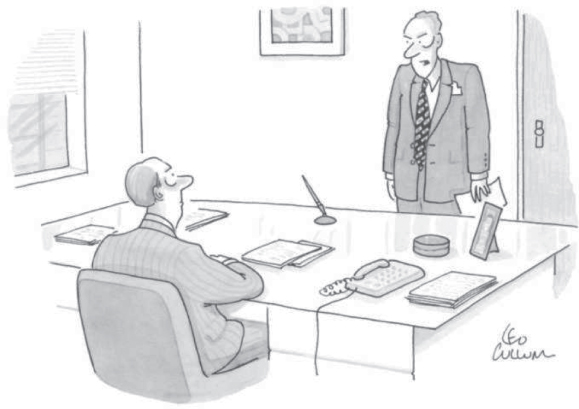

“I do have a fallback position, but it involves firearms.”

Leo Cullum © 1993 from The New Yorker Collection. All Rights Reserved.