* CHAPTER 3 *

HIS OWN MAN

(1938 TO 1945)

Travel would not be too cold, knowing your warmth at my side. ... —Ovid, The Loves

C harlie was all confidence after the breakup. He was going to have a much easier time of it.

“Bill won’t find a lead singer like me,”1 he told Tommy Scott when they met in Bluefield, West Virginia, to discuss working together. “I can always find another man to sing tenor to me.”

And Charlie indeed found an excellent replacement in the person of John Ray “Curly” Seckler. Seckler and Scott worked as Charlie Monroe’s Boys before the formation of a larger band, Charlie Monroe & the Kentucky Pardners.

Charlie had a real advantage over Bill. In contrast to his quiet, shy brother, he was outgoing with personality plus, a big man whom you’d be happy to have on your side in a fight, but also genuinely likable, an affable fellow, the kind you’d be proud to have as a guest at Sunday dinner. Audiences adored Charlie, and he soon found a base at WBIG in Greensboro, North Carolina.

However, he was unable to retain his old sponsors. Neither Crazy Water Crystals nor Syberland Tires wanted to continue with Charlie or Bill alone, fearing that the Monroe boys apart could never be as good as they had been together. So Charlie decided to sponsor himself and turned to a tried-and-true route: patent medicine. During his medicine show days, Tommy Scott had obtained the formula to an herbal tonic and laxative.2 Charlie now bottled it under the trade name “Manoree.” He sold tons of the stuff.

Meanwhile, Bill had moved with Carolyn and Melissa to Little Rock, Arkansas. Bill seems to have had no connections there, but Arkansas was probably as far away as he could get from Charlie and still be within the Middle South. There, he undertook a radical experiment with his music—he organized a band.

It was called the Kentuckians. Little is known and less remembered about Bill’s first attempt at heading a group. There is even scant information on its lineup, but it seems to have included Handy Jamison on fiddle and a cousin of Jamison on guitar. (One source gives Willie Egbert “Cousin Wilbur” Wesbrooks as the bass player, but Wesbrooks did not work with Monroe until later.)3 The Kentuckians performed for three or four months, getting a spot on KARK radio but never recording.

When Little Rock played out, Bill disbanded the outfit and traveled for a month through Mississippi, essentially on an extended vacation.4 Bill and his family eventually went to Birmingham, Alabama, where he checked into the music and radio scenes there. Things proved unpromising, so they moved on to Atlanta, Georgia.

There was good reason to be there. Atlanta was a shining sun of early country music.5 Within its orbit was Fiddlin’ John Carson, whose surprise big-selling 1923 recording of “Little Old Log Cabin in the Lane” had made him the first true star of the nascent country music recording industry; Gid Tanner & His Skillet Lickers, the flamboyant and trend-setting string band; and Clayton McMichen, a jazz- and pop-influenced fiddler who left the Skillet Lickers to become Tanner’s greatest rival. Atlanta was also the site of the Old Fiddler’s Convention, then the nation’s most prestigious fiddle contest, founded in 1913 but with precursor events as early as 1899. And it was home to WSB, which became in 1922 the first radio station to broadcast country music.6

By the time Bill reached Atlanta, he had made a major decision: He would give up trying to lead a band and go back to what had brought him success—a vocal duet with mandolin and guitar accompaniment.

He advertised in the Atlanta Constitution for musicians who could play the guitar and sing old-time songs. The ad came to the attention of Cleo Davis, a guitar player and singer from Cullman, Georgia, then living in Atlanta with a cousin and driving an ice truck for a dollar a day. Cleo was cajoled and finally bullied into auditioning. When Davis protested that he didn’t even own a guitar, his cousin bought one at a pawnshop for $2.40. Cleo relented, put on his Sunday suit, and took a streetcar across town, accompanied by his cousin so he wouldn’t chicken out.

The ad gave no name, only an address that proved to be a lot next to a service station. There sat a small house trailer. The sound of singing and picking came from inside. Some men came out, and the occupant was heard to say he’d call once he’d made a decision. Davis and his cousin entered to find a man, his wife, and their baby.

Introductions were made, but the nervous Cleo missed the man’s name. There was a pause.

“Well,” the man asked, “who plays the guitar?”7

“I do, sir,” said Cleo. He had hidden it behind his back, but now took it out.

“Well, what can you play?”

Cleo had decided to perform two sides of a record by his favorite duet, an act he had never seen in person or even in a photograph—the Monroe Brothers.

“Oh, maybe a verse or two of ‘This World Is Not My Home’ and ‘What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul,’” Davis replied.

This was acceptable to the stranger. They tried to tune up, but the man owned a fine Gibson mandolin and Cleo’s guitar was too cheaply made to take standard pitch. The stranger obligingly tuned down his instrument.

The two only got through about a verse and a chorus of “What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul” when Davis realized he had heard this voice before. This was one of the Monroe Brothers.

Thunderstruck, he stammered and stopped, claiming he had forgotten the words. The mandolin player diplomatically accepted the explanation. They tried “This World Is Not My Home.” Davis got through two verses before stage fright strangled him again. But it didn’t matter.

“Carolyn, what do you think?” Bill asked his wife.

“He sounds more like Charlie,” said Carolyn, “than any man I ever heard who wasn’t Charlie Monroe.”8

A grin spread over Bill’s face. They tried the song again, and their blend sounded even better.

“I think I found what I’ve been looking for,” he said. Davis was told to return the next morning.

Bill Monroe and Cleo Davis set about becoming an act. They first went downtown to the music stores and found a fine new large-bodied guitar that Bill played and approved. (In these days before good sound systems, a guitar with volume was as vital as a singer with lung power.) Davis saw the price tag and nearly ran from the store in fright. It cost $37.50. There was no way he could afford it. No problem. Monroe paid cash, and they carried it away.

The next stop was a clothing store. “Fix him from the floor up,” Monroe told the salesman. The transformation was completed with the purchase of a wide-brimmed John B. Stetson hat. Davis looked at himself in the mirror, pulled the Stetson down over one eye, and thought: James Cagney and George Raft have nothing on me. Monroe liked the effect so much that he purchased an identical outfit for himself.

Monroe’s generosity went beyond the expensive guitar and threads. He proved to be a patient, supportive teacher. Cleo was modest, talented, and hardworking. And he was shy, even shier than Bill himself. Here was someone Bill could nurture, someone to whom the youngest Monroe could play protective elder sibling. Bill had found a surrogate younger brother in Cleo Davis.

Davis was aware of this dynamic in their relationship, as he later told writer Wayne Erbsen:

Back in those days, Bill was more like my older brother than my employer. I looked at him like a big brother, though he wasn’t that much older than me. But he’d been around a lot more than I ever had.

They began rehearsing at Davis’s place after Cleo got off work, for an hour, sometimes two and a half hours at a stretch. Bill was a strong guitarist himself; just as he had learned work skills by silently watching his father, he had quietly absorbed every detail of Charlie’s playing. He taught Davis all of Charlie’s booming, syncopated runs.

This continued until Christmas 1938. After the holidays, Monroe and Davis auditioned for the popular Crossroads Follies show on WSB in Atlanta.

They were turned down.

The show’s manager was only interested in bands and suggested that if Bill picked up a couple more musicians there might be a place for him on the Follies. Monroe made a few well-chosen suggestions about what the manager could do and took his painstakingly rehearsed duet across town to WGST. The managers of that station greatly enjoyed the act, but their duet niche was being filled by the popular Blue Sky Boys, Bill and Earl Bolick.

Angered by this second failure to get back on radio—and therefore all the more determined to succeed—Bill asked Cleo if he could take a few days off work. Soon Davis found himself packed with the Monroe family into Bill’s 1938 Hudson Terraplane, the trailer in tow. Davis asked where they were going. “Asheville, North Carolina,” Bill replied. To the untraveled Davis, it might as well have been Europe.

They stopped first in Greenville, South Carolina. At WFBC, it was a repeat of the WGST disappointment, with the Delmore Brothers the reigning duet. At least Monroe and Davis were being shut out by high-level competition. And it was not that the Bolicks and the Delmores were necessarily better; they were just there first.

They finally reached Asheville—and success. They were hired at WWNC to take over Mountain Music Time. WWNC was a small operation and the program was only fifteen minutes, at 1:30 in the afternoon. Hardly the midday meal prime time at a big station. But it was a start.

The announcer distinctly referred to them as Bill Monroe and Cleo Davis, but mail started coming in addressed to “the Monroe Brothers,” proof that they had captured the old magic. He and Davis expanded their repertoire to include material associated with the Delmores and the Callahan Brothers, but they kept developing their own sound, working up a breathtaking blue yodel duet as a theme to take them on and off the air.

Bill was not going to clone the Monroe Brothers or other duets. Maybe because of his initial creative impulses with the Kentuckians, maybe because of the realities of laboring in a field already lush with outstanding duets, he decided to try again at being a bandleader.

Davis asked what they were going to call the new group.

“Bill Monroe and His Blue Grass Boys,” his employer replied.9

Davis was puzzled. Blue grass? Monroe explained that it would facilitate quick identification of his home state. “I’m from Kentucky, you know, where the bluegrass grows, and it’s got a good ring to it,” he said. “I like that.” The matter was settled, the new band named.

In Asheville, Monroe renewed the search for sidemen, turning not to the print ads that had brought Davis but the most powerful and specific advertising medium he had at his command—his own radio show. He announced on the air that he was looking for musicians. They started showing up, and Bill and Cleo started auditioning them.

Art Wooten, a fiddler from the nearby town of Marion, was the first to be hired. Monroe already had in mind the kind of fiddle sounds he wanted, and began working with Wooten, playing the parts he wanted on his mandolin, coaching him verbally on the bowing. If Cleo Davis proved to be the first of a very long roster of Blue Grass Boys, Art Wooten was the first of a host of fiddlers to be schooled by Bill Monroe.

Monroe began to develop a total entertainment package for his live shows. There was, of course, the music. The Blue Grass Boys would open with a fast fiddle instrumental like “Fire on the Mountain” or “Katy Hill,” then keep the energy level high with a fast duet like “Roll in My Sweet Baby’s Arms” or “Foggy Mountain Top.” There were blues numbers and yodel duets. Gospel music was not neglected: “What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul” always got a huge audience response, not only as a stirring song but one of the Monroe Brothers’ greatest hits.

And there was more: Wooten played a strange contraption with a guitar and a banjo built into it, designed so Art could strum and chord these instruments with his feet while playing the fiddle. Adding a harmonica in a holder around his neck, he performed novelty numbers as a one-man band.

Monroe continued to power up the act. He hired Tommy Millard of Canton, North Carolina, to play jug (thus providing the band with some rhythm bass notes) and do comedy. Millard was such a wickedly effective blackface rube comedian that only the stoic Monroe could play straight man in the wacky skits the band developed.

Bill was now starting to sing solos. One of his first was the sentimental Tm Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes.” Only freshly out of Charlie’s shadow and probably unsure how he would go over, Bill hedged his bets: He used the song as the basis of a comedy routine. Millard would come out in blackface, begin to weep, then lean on his shoulder and dissolve in tearful spasms while the audience went into paroxysms of laughter.

Bill took other roles in the comedy routines. He and Davis got into drag to portray sisters; Cleo would fuss with jealousy over Bill’s hot date with Art Wooten until Tommy Millard came on stage and bopped Davis alongside the head with a rolled-up newspaper.

Bill was emerging as his own man. He was in total creative control, he was happy, he was singing solos. Even his hidden childlike playfulness was emerging into public view.

And he continued to be a truly supportive bandleader. One night, Davis forgot a verse to a song. Monroe quickly played an extra mandolin break, but Davis panicked. Bill grinned and waited patiently, and Davis suddenly just made something up, stringing some words together. The band then went offstage to prepare for the comedy skit.

The audience had not noticed anything amiss, but Davis was convinced that he had humiliated himself. “Bill, I don’t think I can go out there and face those people again,” he said.10

Monroe did not laugh or mock, nor order Davis to take the stage. He regarded his frightened sideman calmly.

“You have to go back out there,” he said. “Not for me but for yourself. If you let this stop you, you’ll never be able to go back out again. You have to prove to yourself that you can do it. You can do the job. You just got scared, and it won’t happen again.”

Cleo Davis finished the show without a hitch. He stepped off the stage that night a confident veteran.

While Bill was nurturing his musicians, Carolyn was nurturing her husband’s career. Gone was her detached attitude from the tense days of the Monroe Brothers caravan. She was no longer the pregnant girlfriend who had shamed Bill into marrying her. Nor was she subjected to the smoldering tensions between Bill and Charlie. All that was over and done. The couple was enjoying a fresh start.

Carolyn was now fully Bill’s wife and partner.11 Her supportiveness, which had budded during Davis’s audition, now blossomed. She took care of the mail that began coming in for Bill at the radio station. She assumed an active role in booking the band, traveling around to the schoolhouses that served as theaters, making arrangements, putting up handbills to advertise the shows.

Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass Boys had less work than the Monroe Brothers had enjoyed, they were performing at small schoolhouses holding seventy people at most, and now there were two extra musicians to be paid. Even if they played two shows, with ticket prices 15 or 25 cents depending on age, they might take in only $25 or $30 a night. The band members got $15 a week when they were working, nothing when they weren’t (although Bill, committed to having his sidemen looking sharp, always paid for haircuts and laundry).

Things were reaching a crisis. How Charlie would guffaw if his kid brother fell on his face!. But after the group had been at WWNC about three months, word came that the Delmore Brothers had left WFBC in Greenville, South Carolina. Remembering the genuine interest that had greeted him there, Bill contacted the station. This time, success. The band was hired immediately.

Relocating to Greenville, Bill took another major step toward establishing his sound. Millard left the show and was replaced by Amos Gar-ren. Amos sang and did comedy, but best of all he played standup bass. The Blue Grass Boys now had a solid bedrock for Davis’s fertile rhythm guitar, the strong shoots of Wooten’s fiddle, and the bark of Monroe’s mandolin.

Money was still tight, and home was still the trailer. It was parked, as it had been in Atlanta, next to a service station. The owner took an interest in Bill and offered an old grease house as a rehearsal space. The band cleaned it up and brought in seats. Then they started assembling and lubricating new material.

None of it was original but it was customized for this sleek string band of fiddle, mandolin, guitar, and bass backing sharp leads, soaring duets, and finely tuned quartets. The band continued to emphasize high-octane instrumentals and vocals, but its repertoire gained variety and depth. They rehearsed trios and gospel quartets. Bill and Cleo worked up “No Letter in the Mail,” a Carlisle Brothers number. Although in waltz time, Davis slowed it down even further and the song took on a bluesy, almost despairing edge, a harbinger of the trademark Monroe “high lonesome” sound, which would come to fruition a decade later.

His confidence growing, Bill began to learn more solos. Davis suggested a vocal he had heard his mother sing when he was a boy, “Footprints in the Snow.” This tale of love discovered on a winter’s night would become one of his most popular vehicles.

An even greater classic was rebuilt, tuned up, and readied for the road in the old grease house. Monroe decided to arrange some Jimmie Rodgers favorites to suit his coalescing style. His tenor range had developed as a matter of survival with Charlie; now the intensely competitive young man was ready to show the world how a “blue yodeler” number should really be yodeled. He selected two of the Rodgers “blue yodels” songs, including “Blue Yodel Number 8.” Better known as “Mule Skinner Blues,” it was the engaging braggadocio of a mule team driver who can whip the recalcitrant beasts into cooperation and cracks his way through life in the same style. The higher-than-usual keys Bill selected put an extra edge on these numbers, like a knife honed to a razor’s edge. But unlike a thin-honed knife, the slicing blade of Monroe’s voice was in no danger of bending flat. A nonsmoker and nondrinker with a powerful chest, Monroe was a sheer ax of a singer.

Rodgers had performed “Mule Skinner Blues” in his trademark style: slow, almost drawling vocals; odd-tempoed guitar rhythms; thoroughly influenced by the country blues. Monroe sped up “Mule Skinner” and gave it a more regular rhythm. But he did something more. At this stage, Monroe typically played guitar when he sang leads, trading off the mandolin to Davis. Monroe kicked off “Mule Skinner” with a very funky staccato run, then immediately went into a powerful rhythm strum. The band leaped in, pulled along by the crack of Bill’s symbolic whip over the mule team.

Bill’s rhythm was special. It was a surging timing that anticipated the main beat. Not in a way that sped up the song but in a way that totally enlivened it. It was like the blues or jazz technique of laying slightly behind the main beat to create dramatic impact, except in reverse: Bill Monroe subtly jumped the timing to create energy. Monroe fully recognized the significance of his innovation, later declaring that “’Mule Skinner Blues’ set the timing for bluegrass music.”12

Also in his music were “the Negro blues,” as he called them, yet only a spicing. Too much of their influence, Bill felt, would overpower its other flavorful elements. Much of the Monroe “lonesome” sound actually came from Methodist, Baptist, and Holiness church singing13 and Bill’s own emotions. “It ain’t only the colored folks has the blues; there’s many a white man that’s had ‘em,” Monroe later said. “I’ve had ‘em many, many times.”14

Above all, there was the fire and speed and sheer drive of Bill’s music. Other southern string bands had spunk aplenty, but compared to the Blue Grass Boys they were just dragging along. Monroe’s music also got a major boost from the higher keys in which he pitched many vocals. His decision to sing, for example, in keys like B-flat and B—instead of the G or A favored by most country vocalists of the day—had originally been an expedient to better suit his range: It had the unexpected benefit of putting the keening—and compelling—high element into Monroe’s high, lonesome sound.15

Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass Boys made Greenville their home base for about six months. In a short time, Bill had gone from junior partner to Charlie to being a leader of fortitude, patience, and courage. Now he was about to prove himself to be a true risk taker.

For their part, Charlie Monroe & the Kentucky Pardners were doing quite well. Their music had less of a hard edge than that of the Blue Grass Boys or even the Monroe Brothers, more flowing in its timings, its song material more sentimental. Charlie’s garrulous personality and convivial show drew big crowds and won him a spot on the popular WWVA Jamboree in Wheeling, West Virginia, another successful rival to WSM’s Opry and WLS’s Barn Dance. Although WWVA’s signal was much less powerful than that of WSM or WLS—l;000 versus 50,000 watts—it reached near-South and midwestern states densely populated with country music fans.

But Charlie had plans. Big plans. Early in October, his confident, happy smile on his face, he gave his band the news.

“Well,” he said, “we’ve got a chance to go down and try out for the Opry.”16

Carried on WSM, Nashville’s powerful 50,000-watt station, The Grand Ole Opry was eclipsing the WLS Barn Dance as the nation’s premier country music program. WSM, 650 AM, was owned and operated by the National Life and Accident Insurance Company, headquartered in Nashville, Tennessee. Its call letters came from National Life’s motto: “We Shield Millions.”

The station had been the brainchild of Edwin Craig, a National Life vice president and a radio nut as obsessed with new communications technology as any modern computer geek. As son of the company’s president, twenty-nine-year-old Edwin was able to convince the board of directors to build a radio station, emphasizing its potential for advertising National Life’s policy services. WSM went on the air October 5, 1925. At one time, it had the tallest radio tower in the United States. Eventually granted “clear channel” status, with exclusive use of its frequency within a 750-mile radius of Nashville, WSM was heard at even greater distances, throughout the South and Midwest, and, during good atmospheric conditions, to an estimated thirty-eight states and parts of Canada.

As in all early radio, there was virtually no use of recorded music. Entertainment on WSM was live. And there were no country or “hillbilly” artists on the station at first. In keeping with the high tone of Nashville (“The Athens of the South”) and National Life’s dignified corporate image, WSM presented classical and semiclassical soloists, refined harmony groups, and instrumental ensembles.

The hayseeds were sown at WSM when Indiana-born George D. Hay was hired as program director. A former newspaper man, Hay had attended a backwoods hoedown in Mammoth Spring, Arkansas, and gotten hooked on authentic, foot-tapping mountain fiddling. In 1924, he became chief announcer for the WLS Barn Dance. With his enthusiasm for the music, his persona as “the Solemn Old Judge” (at the ripe old age of twenty-nine) plus his gimmick of blowing a steamboat whistle to open and close the show, Hay had been a natural for the show.

On the evening of Saturday, November 28, 1925, contest-winning octogenarian fiddler Jimmy Thompson performed on WSM accompanied by his niece Eva Thompson Jones on piano. They evoked such a favorable response that they became a regular Saturday night feature. This was essentially the birth of what would become The Grand Ole Opry.17

Throughout the heartland, the old tunes were heard with joy. Cards, letters, telegrams, and phone calls poured in, pleading for more. By December 26, a regular two-hour program of old-time music was being broadcast live each Saturday night from the WSM studios. Joining the growing cast of regulars was David Harrison “Uncle Dave” Macon, a.k.a. “The Dixie Dewdrop,” a former freight line operator and rollicking banjo picker who, at age fifty-two, became the show’s first real star.

Initially known as the WSM Barn Dance, the broadcast attracted a live audience that filled the WSM studios beyond capacity. And one night a comment was made that would echo through American popular music history. The Barn Dance was following the nationally broadcast Music Appreciation Hour, featuring the New York Symphony orchestra and carried via a feed from the NBC radio network. Introducing the Barn Dance that fateful evening, George D. Hay ad-libbed, “For the past hour we have been listening to music taken largely from Grand Opera. From now on, we will present the Grand Ole Opry.”18

The name stuck, and the show grew. Hay now concentrated on his hit program, and Harry Stone replaced him as station manager. By 1930, the Opry had thirty regular cast members and audiences so large that WSM built a special 500-seat studio theater, which quickly proved too small as the program became as much a live event as a radio broadcast. The Opry was forced to move twice. In 1939, it landed at the then-new War Memorial Auditorium. A 25-cent admission was charged for the first time in an unsuccessful attempt to reduce the throngs.

Soon the Opry had its first modern star—Roy Acuff, who debuted in 1937 and joined as a regular member in 1938. Acuff was the first great country “heart” singer. He oozed sincerity. His version of “Wabash Cannon-ball” quickly became a country anthem, and while performing emotion-filled numbers like “Wreck on the Highway” and “Great Speckled Bird” the tears would literally stream down his face.

So in planning to go to the WSM Grand Ole Opry, Charlie Monroe was making a brilliant career move. The trip to Nashville, he told the Kentucky Pardners, would be taken in about two weeks.19

But unbeknownst to Charlie—unbeknownst to anyone—his younger brother had exactly the same plans.

“What do you think about us going on The Grand Ole Opry?” Bill asked Cleo Davis one day.20

“Do you think we’re good enough?” Cleo gaped.

Bill laughed. “We’re as good as the best over there, and right now, we’re better than most of the rest.”

Bill had been paying very close attention to what was going on at WSM. It would be this way for the rest of his life: The laconic Monroe, driving along, listening in deceptively casual silence to the radio, seeming to just enjoy the music. But in fact he was making mental notes, assessing the strengths and weaknesses of other performers, of stars and sidemen alike, weighing what he heard—and remembering.

“Tell the other boys to get their toothbrushes ready,” Bill said. “We’re going to Nashville.”

Bill Monroe crossed the Cumberland River into downtown Nashville like George Washington crossing the Delaware and marching on Trenton, New Jersey, steely determined yet at a moment of crisis, desperately needing a victory. Bill and the group went to the WSM offices and studios, located then on the top floor of the five-story National Life and Accident Insurance Company building at Seventh and Union streets. Getting off the elevator, they encountered David Stone, a WSM executive, and George D. Hay.

Right away, problems. Stone and Hay were headed out to get coffee, and anyway Monday was not audition day, Wednesday was. But they were persuaded to hear Monroe’s band after lunch.

That afternoon, Hay and Stone ushered the ensemble into a studio. They turned on the microphones—the Blue Grass Boys were no good to WSM if they couldn’t work in front of a mike—then sat back in the control room and waited.

Filled with nervous energy and as ready as they would ever be, the Blue Grass Boys tore into the audition. They started with “Foggy Mountain Top/’ a familiar, upbeat Carter Family number done by Monroe and Davis as a crackling duet. Bill trotted out his arrangement of “Mule Skinner Blues/’ and finally Wooten was featured on “Fire on the Mountain.” The audition had encompassed a favorite old standard with an athletic duet, an innovative solo, and finally a foot-tapping fiddle number.

Hay was impressed. He thought: This is a big, good-looking fellow, and he’s just given us a sample of folk music as she should be sung and played. He’s exactly what the show needs.21 Hay asked if the band could open the Opry that Saturday night, first spot.

“Yes, sir,” Monroe replied.

“Well,” said Hay, “you’re here, and if you ever leave, you’ll have to fire yourself.”22

Hay came to genuinely like Monroe, although Bill could be a standoffish person. In his 1945 book .A Story of the Grand Ole Opry, Hay ended his entry on Bill with these words and much between the lines: “Bill Monroe is a good citizen and the longer one knows him the better one likes him.”23

Now the Blue Grass Boys had some heavy traveling to do. They returned to Greenville, South Carolina, picked up Carolyn, Melissa, and the trailer, then blazed back to Nashville, a journey of at least four hundred miles each way. They arrived well in time for their first Opry appearance on October 28, 1939.

Monroe’s overall timing was excellent. Not only was Opry becoming America’s most successful country music radio show, it was beginning to be heard nationwide. On October 14, a half-hour segment had been carried for the first time on the NBC “Red” network, a system of twenty-six stations. And the show’s cast was starting to change. The original members had been local hobbyists, old-time fiddlers and banjo pickers. Now a new breed was arriving from greater distances, performers like Acuff and Monroe, modern full-time professionals—and vocalists.

* * *

The Solemn Old Judge announced Bill Monroe & His Blue Grass Boys’ first Opry appearance, and the band tore into “Foggy Mountain Top.” The audience loved it. The music had originality and sheer energy. Then Bill took the guitar and sang “Mule Skinner Blues.” It was Bill’s first vocal solo on the Opry show and the true debut of his innovative arrangement of the Jimmie Rodgers classic. (Prior performances had been in little school-houses, after all, not live over a 50,000-watt radio broadcast.) They got an encore, an Opry first.24

The Blue Grass Boys left the stage with the live audience cheering, the home listeners excited, and other Opry performers suitably impressed. They had traveled a long, long road from the Greenville grease house to the stage of the War Memorial Auditorium.

Up in Wheeling, West Virginia, Charlie Monroe & the Kentucky Pard-ners had finished the first of their two segments on the Jamboree. In the dressing room, they tuned in to WSM and heard the Solemn Old Judge announce the new band.

Thunderstruck—knowing that his kid brother had beaten him to the Opry by a mere fortnight and that George Hay would never hire both Monroes for the show—Charlie jumped up and left the room.25

Later, after regaining his composure, he breezily dismissed this development. “He won’t last,” he told Tommy Scott.26 “Wait ‘til people down there find out how difficult he is to get along with.”

In fact, it was Charlie who didn’t last at WWVA, leaving the station after an argument with the program director.27 Inwardly, Charlie was frustrated. He refused to let matters rest there, as sideman Curly Seckler recalls:

I’m not saying anything against either of them, Bill or Charlie. But one was jealous of the other one. Of course, WWVA in Wheeling was only a 1,000-watt station. Bill was down at WSM which was 50,000 watts. Charlie said he wasn’t going to be outdone, so he was going to go to WHAS in Louisville, a 50,000-watt station, to be up with him. You know, I don’t get that. He was making pretty good money at Wheeling. In Louisville, no sponsor, no nothing. But he didn’t want to be outdone. It’s something for brothers to have been that way, but that’s the way they was.28

Bill had won a big round in the Monroe brothers’ unspoken competition, and his Blue Grass Boys began a string of Opry firsts: In addition to their historic encore, they became the first band to perform gospel quartets, again raising the vocal standards on a show that had started as a fiddlers’ frolic.

Another first was not musical, but in its own way just as significant: Monroe’s musicians were the first to play as part of the Opry stage show wearing ties and white shirts. They still wore Stetsons, but Bill had gone back to the natty jodhpur riding pants and high-top riding boots that the Monroe Brothers had featured at the end of their career. This gentleman planter’s uniform would be retained for the next three or four years.

Early Opry performers had arrived at the WSM studios respectfully dressed as if going to church. But as the show attracted a live audience and publicity photos were published, Hay had encouraged them to wear hillbilly outfits to communicate the show’s rural orientation. But this, Monroe believed, created stereotypes calculated to attract urban sophisticates engaged in a musical slumming expedition.29 (Monroe even hated the self-deprecating term “hillbilly music” and took immense satisfaction when it was supplanted by “folk” and then “country” to describe rural southern sounds.)

Corny country comedy with funny costumes had a place in Bill’s early shows. (Until the early 1960s, a succession of Monroe sidemen portrayed “Sparkplug,” a rube dressed in a loud shirt, baggy pants, and skewed baseball cap.)30 But in the main, the Blue Grass Boys were sharply attired and all business on stage. Real country people had pride and dignity, and they dressed as well as their economic situations would allow. A houndstooth jacket and an upright bearing were the hallmarks of a gentleman in western Kentucky. Monroe’s formalization of attitudes and clothing for his band was actually more faithful to real country life than the antics of ragged pseudo-mountaineers.

As fiery as Bill’s Opry debut had been, he did not shoot to stardom immediately. In the spring of 1940, he was touring with the tent show of comedian-showman Silas Green (“I’m Silas Green from New Orleans!”) at the bottom of the bill, beneath Uncle Dave Macon and fancy fiddler Curly Fox.31 By the end of the year, Bill’s band had completely changed, but if anything, it was even stronger: On fiddle was now the able Tommy Magness; the great bass-playing comedian Egbert “Cousin Wilbur” Wes-brooks had joined the lineup; and Clyde Moody had replaced Cleo Davis, the original Blue Grass Boy, who had got his own radio show in Lakeland, Florida.32

Davis just missed the Blue Grass Boys’ first recording session on October 7, 1940. Bill had signed again with Victor Records, and the session was held in the Kimball Hotel in Atlanta. (Nashville was not yet a recording center.) Monroe opened the proceedings with his Opry debut hit “Mule Skinner Blues,” but the day’s final selection was the true harbinger of things to come: the instrumental “Tennessee Blues.” It was Bill’s first original composition,33 and it was a winner.

Bill was now truly his own man. His persona and his music were coalescing in tandem.34

First and foremost, he was a striking figure. A six-footer, his solid body, balanced posture, and confident manner made him seem much bigger. He would rarely lean against anything or put his hands in his pockets. He would stand on his two feet and let his arms hang comfortably at his sides.

He was unhurried but had a ferocious work ethic. His strength was very real, truly that of a Highlander of yore. Once around this time, for a lark, he invited his band to get on him: One sat on his shoulders, one climbed on his back, and he held the other two in his right and left arms, easily supporting them all.35

Bill’s physical strength and balance had a mental counterpart. It was difficult, even impossible, to pull him off balance physically or psychologically. It was usually Bill who subtly led others around. He measured his words carefully and rarely responded without thinking, although when he spoke his sentences sometimes came out rapidly. Things he said to people made such an impression that years later they could recall his utterances as vividly as if they had been made that morning.

Outwardly, he seemed inaccessible and impervious. He was proud. But inwardly, his feelings could be hurt easily. When he was angry, he rarely lashed out. He would instead turn cold and stop speaking to the person who had offended him. The length of his feuds was matched by the constancy of his loyalties, especially to family members.

He had rawhide-tough willpower. Intertwined with that willpower, and reinforcing it, was a gristly stubbornness. He was supremely competitive, especially with other men. This extended to his art, and he believed that spirited competition within the otherwise friendly teamwork of the band peaked the music to its greatest heights. (In a significant choice of words, Monroe would often praise a lead vocalist not as being a good man to sing with but as possessing “a good voice to sing against.”) Musically, physically, romantically, he would never allow himself to be bested without putting up a fight, and he seldom lost. Yet he did not fight physically unless attacked or provoked. (One provocation was rowdiness at his shows; if a heckler turned up, Monroe was known to put down his mandolin, go into the audience, throw the loudmouth out, then return to the stage—often before the song was finished.)

He did not boast of his strength or his talent or his romantic conquests. He rarely cursed and hated to hear others use such language. In particular, he would not tolerate foul speech when a lady was present. He was impulsive in love, perhaps even compulsive, but he never forced himself on a woman. He would accept no for an answer.

He had clear blue eyes and tended to stare down his nose at people or seem to look right past them. Although he could truly be aloof, this behavior was often caused by poor vision. (He hated to wear his eyeglasses in public.) He appeared very reserved (like the Monroes) but had a lively sense of humor (like the Vandivers). When something struck him funny, he would laugh merrily. He treasured the celebration of Christmas.

He had escaped the farming life, yet he truly was a man of the soil. He loved what he called “Mother Nature.” One of the few modern technologies that he seemed to really embrace was the telephone.

He loved Tennessee walking horses and foxhunting. He was a Democrat. He savored fried potatoes and fried chicken and baked beans. Donuts and peanut butter were a favorite snack. He had the eccentric habit of wetting himself down in the shower, turning the water off, stepping out of the tub, lathering himself up with soap, then stepping back into the tub, turning on the water again, and completing his shower.

He took scant interest in business matters, but he hated the idea of anyone making money off him and was suspicious of those who came to him with business deals. He was usually a good judge of character, and once he accepted a person he trusted that person implicitly. When he didn’t have money, he was stingy. When he did, he was touchingly generous. He never used money to buy friends or impress people. The thick wad of cash once given a poor vendor so Monroe could buy the man’s undernourished cart horse and provide it a new home on his farm; the quarters he gave children (a memory of the coins given him by his father); the appearance fees often returned at benefit concerts—all these gifts of money had deliberate thought and feeling behind them. He was a man of action. But he was very, very thoughtful.

His married life appeared stable. He and Carolyn seemed happy together, and on March 15, 1941, their second child was born, James William Monroe.36 (Bill had named his daughter and son after his parents, but no Freudian subtext should be read into this. It was common practice in the Monroe family to thus honor relatives and forebears.)

Almost exactly a year after the first Blue Grass Boys session, on October 2, 1941, the band was back at Victor’s studios in the Kimball Hotel in Atlanta to cut another eight sides for the label. The lead singer-guitarist slot was proving to be a springboard that launched careers: Pete Pyle had replaced Clyde Moody, who had gone out on his own (although Moody would return for another hitch with the Blue Grass Boys the following year).

Art Wooten, back on fiddle, was featured on a very hot instrumental with vocal bridge—“Orange Blossom Special”—written in 1938 as a rousing tribute to the New York-to-Miami streamliner by Florida-based fiddler Ervin Rouse of the Rouse Brothers. The number had been brought into the band repertoire by Wooten and Cleo Davis,37 and the Blue Grass Boys’ 1941 version helped establish it as country music’s most popular fiddle showcase.

The session ended with the instrumental “Back Up and Push,” with Wooten and Monroe trading breaks, anticipating the jazzlike soloist-friendly format that would distinguish bluegrass, Wooten stating and brilliantly restating the melody, Monroe providing fiery variations.

What was happening behind the fiddle was just as significant. In this period, when Bill wasn’t soloing he strummed his mandolin in a shuffling rhythm inspired by Uncle Pen’s bowing or played counterpoint lines. But from time to time on “Back Up and Push” he added a strong, straight downstroke on the second and fourth beats. It was an early example of the “rhythm chop/’ the backbeat emphasis that added yet another dimension to the mandolin. Monroe had been using the instrument like a fiddle, guitar, or even a banjo. Now he was starting to use it percussively, like a snare drum.

Despite their musical discipline, these Blue Grass Boys would josh like a jug band, even bantering on records just as they’d do onstage. And because many a true word is said in jest, the joking that accompanied the Jimmie Rodgers/George Vaughn number “Blue Yodel No. 7” had a deep meaning indeed.

Monroe sang the verse celebrating the singer’s love for Mississippi and Tennessee, throwing in a quick aside “Give me Kentucky, boy!” in tribute to his native state. Then he finished with the standard punch line that the women in Texas “done got the best of me.”

“North Carolina women get him,” gibed a band member, probably bassist Wesbrooks.

There can be no doubt as to the reference. A North Carolina woman had indeed got him. And as much as Bill genuinely cared for the mother of his children, if longevity of a relationship is any measure, this other woman was the great love of his life.

Her name was Bessie Lee Mauldin. She was born December 28, 1920, in the town of Norwood in Stanley County.38 She was the third of four daughters of Samuel Lee Mauldin and Lilly Thompson Mauldin. Lee Mauldin was a mechanical genius, “a fixer” who could repair just about anything he could get a tool around. He held an important position as a machinist and operator at Norwood Manufacturing (later Collings & Akeman Co.), a large textile mill and the major local employer. The Mauldin family lived next door, in a two-story house.

Mr. Mauldin could pick the five-string banjo, a popular instrument in North Carolina. Bessie did not immediately learn to play an instrument herself but had a sweet voice. As a child, her family had to beg her to dance, but once she got started they had to beg her to stop. When she was older, she enjoyed going to square dances at the Norwood Hotel.

She was a very good cook. She was mischievous. She always seemed to know how to get her sisters in trouble while cleverly escaping a spanking herself. When Bessie went too far; one sister would lock her in the outhouse, knowing that Bessie was claustrophobic. Bessie would scream and holler and the sister would get a whupping but it all was worth it. The sisters had a lively childhood and loved each other very much.

Bessie grew into a very attractive if rather hefty blond woman, a flashy dresser, strong, spirited, and quite earthy—just Bill’s type. It is believed that they met at a show in Albemarle, North Carolina, not far from her home.39 But the act that night, it seems, was not the Blue Grass Boys. It was the Monroe Brothers.

Persons close to Bill had the impression that he had met Bessie not long after meeting Carolyn.40 And in a 1975 legal filing, Bessie claimed that “on or about September, 1941 ... at the age of 17” she was “lured” by Bill “from her home and family in Norwood, North Carolina.”41 The lurid use of “lured” aside, the statement is inaccurate: Bessie would have been twenty-one or twenty-two at that time. However, it is likely that she meant (and her attorney misunderstood) that she originally met Bill at age seventeen, probably in 1938, then moved to Nashville in 1941.

Bessie later claimed she and her parents were unaware for some time that Bill was married.42 As doubtful as that seems, it is likely that Bill eventually told her the circumstances of his marrying Carolyn to explain why he was not free.

In September 1941, Bill brought Bessie to Nashville and installed her in a hotel.43 She became his road girlfriend. The pattern was the same for years:44 The Blue Grass Boys would start to leave town; Bill would stop at a pay phone and make a call; Bessie would then meet them at a designated pickup spot to join him for the trip. Meanwhile, Carolyn was keeping their house and Bill’s books, keeping family and business together.45 The arrangement worked for a long time, because Bill was spending a lot of time on the road.46 But Carolyn knew full well what was going on.47

Bessie’s move to Nashville occurred just prior to the October 2 recording session. Given that she was now traveling with Bill outside Nashville, it is possible, even likely, that Bessie was sitting in the studio in Atlanta when “Blue Yodel No. 7” with its impromptu gibe about North Carolina women was recorded. Whatever the case, the fact that Bill and the band felt free enough to joke about Bill’s affair—on a record that would be heard nationally—is sad evidence of how little concern they gave Carolyn’s feelings in the matter.

Nashville’s city fathers were becoming rather unhappy with WSM’s hit show. The War Memorial Building had been intended for long-term use as a concert hall and theater; now it was receiving serious wear from thousands of Grand Ole Opry fans visiting it each week. In 1943, a new venue was found that would be the Opry’s temple during its golden era—the Ryman Auditorium.

In 1891, Tom Ryman, a riverboat captain and shipping company president, experienced salvation and caused the brick-built Union Gospel Tabernacle to rise on a hill overlooking Nashville’s commercial and saloon districts.48 The building eventually became an all-purpose auditorium renamed in his honor. With the construction of a great balcony to accommodate an 1897 convention of Civil War veterans (henceforth known as the “Confederate balcony”), the Ryman attained a capacity of more than 3,000 seats. Its oaken pews were uncomfortable and the lack of air conditioning made the jam-packed place almost unbearable in summer. But the semicircular seating arrangement focused attention on the stage and gave audience members a feeling of shared intimacy. Best of all, the Ryman had superb acoustics. It had been a successful concert venue. (Enrico Caruso, John Philip Sousa, and Jeanette MacDonald had all appeared there.)49 Now it proved ideal for the Opry’s presentation of country music.

Opry rules were very strict at this time: Cast members were expected to appear on the show every Saturday evening. (Although this precluded Saturday night show dates for the cast members, at the time it didn’t matter much: Most of the fans would be at home tuning into the Opry anyway.) From Sunday through Saturday morning the performers were at liberty. Some veteran cast members, essentially talented amateurs, were content to stay at home. Bill Monroe was one of the new Opry professionals, and he reveled in what he called “heavy traffic.”

He toured almost constantly during the 1940s,50 working as much as six or seven days a week and doing as many as four shows a day. The Blue Grass Boys were now regulars on the 10 p.m. Opry segment sponsored by Wall-Rite, a paint manufacturer. After performing, they would usually head right out on the road for an all-night and all-next-day drive to the first of the week’s gigs. The band drove in a 1941 Chevrolet airport stretch limo with four seats. It handled well and went fast. Bill often took the wheel himself in those days, a swift but cautious driver.51 Despite the extra seats, the musicians and their luggage were crammed inside, with the bass fiddle and other instruments in a special rack strapped to the roof.

Bill was a demanding but fair boss. He continued to look after his side-men as if they were his younger siblings, except he treated them with far more caring attention than he had received as a child. A band member who came down with a cold would be put to bed to rest before the next show. Monroe would bring medicine and regularly check on him.52

In 1942, Monroe began touring with the tent show of Jamup and Honey, the popular Opry blackface comedy duo. After a year of this, he decided to start his own tent show.53 He initially worked with Billy Whal-ley of Miami, Florida, who provided the canvas while Monroe filled it with entertainment. It proved so successful that Monroe invested in his own equipment and for the next three or four years ran the entire show himself. It was another manifestation of a lifelong pattern: Just as Bill had resisted Charlie’s idea of hiring a manager for the Monroe Brothers, he was often unhappy with middlemen, agents, and others profiting from him, even if their percentages were reasonable and, in the long run, they made money for him.

At its peak, Bill Monroe’s tent show was a marvelous enterprise, not simply a band under canvas but a circuslike total entertainment experience. The advance person was first in town, getting the necessary permits, renting a field or lot, putting up posters and window cards, and taking out newspaper ads. About sixty-five dollars would cover it all, and to Monroe it was money well spent. “After you got a lot permit for the show, there was nothing anybody could do to give you any trouble,” he said.54 “It was like owning your own house, until you left the next day.”

The crew soon arrived to set up the tent and concession stand, lights, sound system, and generator. In addition to the stretch limo, the show had five separate trucks to haul the tent, the tent poles, the seats and bleachers (nearly a thousand seats in all), an electric generator, and a rolling kitchen. Of course, the procession drove through each new town to promote the show.

But the pre-concert ballyhoo didn’t stop there. For several seasons, the show featured a semiprofessional ball team.

“We’ve got a team that’s real good,” one of the Blue Grass Boys would declare.55 “Do you have a team around here?”

In this era, many American small towns did. A game was quickly organized at the local field. Despite having one weak eye, Monroe played. He was hell on bats, breaking many as he smashed into pitches.56

It was excellent promo. Country music fans liked baseball, and baseball fans liked country music. With a large crowd now gathered, after the last pitch the Blue Grass Boys would make a pitch of their own, quickly setting up a microphone at home plate and playing a short set to preview what ticket buyers would enjoy at the evening’s show.

(Monroe remained a devoted baseball fan. During the prosperous years of the 1940s, he even ran two clubs:57 the Blue Grass Boys Ball Club, which consisted of band members and ringer athletes and traveled on the road, and the Blue Grass All Stars, based in Nashville. Student baseballers from Vanderbilt University in Nashville who yearned to keep playing over the summer break would start coming to Bill’s shows in the spring, asking to be hired for his teams.)

Admission to the show was sixty cents for adults, thirty cents for children. The band gave an hour-and-a-half performance. The concession stand would sell Cokes, peanuts, popcorn, and Grand Ole Opry souvenir song and picture books. Monroe sold his own popular songbook, which featured a cover picture of him and King Wilkie, his Tennessee walking horse.

Monroe learned early on that as the boss, he had to be tough enough to outwork or even outfight the top roustabout, otherwise the crew would dawdle.58 He was tough enough.

The tour pulled in for one show badly behind schedule. Faced with the need for a quick setup, the show hired extra manpower in town. One local was driving tent stakes with a member of the tour, a big fellow in work clothes.

“Show sure is late getting here,”59 the townie said, alternating sledgehammer strikes with the stranger.

“Yessir,” the other man replied, powering his own hammer down.

“I wonder when Bill Monroe’s gonna get here.”

“Don’t you worry/’ snapped the show worker. “He’ll be here.”

One can only imagine the man’s astonishment when he took his seat that night, looked up at the stage, and realized that he had been driving stakes with Bill Monroe himself.

The bass fiddle would already be lying on the stage. Suddenly, the band would run out and the bass player would stomp on the instrument’s metal stand pin. The bass would spring up into his hands and the band would tear into the first notes while the audience cheered. There would be fifteen or twenty minutes of music with the Blue Grass Boys, then a fifteen-minute interlude of comedy. Then the group would return with gospel quartets followed by more hot instrumentals On some tours, Bill would ride up on King Wilkie and have the horse perform some tricks.60

There was always comedy on these shows, and much of it was still being done by white comedians in blackface. Monroe cheerfully employed such acts and occasionally used racially tinged humor in private conversation. (One of his favorite gibes at musicians who had grown beards or long hair was that they “used to look like a white boy.”)61 But Monroe was not a racist, as witness his relationship with DeFord Bailey.62

Bailey was a phenomenal harmonica player who had come to the Opry in 1925. For years, he was among the Opry’s most popular stars, famed for his renditions of “The Pan American” (in which he imitated a rushing train) and “The Fox Chase” (in which he reproduced a hunting horn and baying hounds). Monroe hired Bailey as an attraction, and what followed speaks volumes about Bill’s attitudes toward African-Americans in that day and age.

Having Bailey on tour might have caused dissent in the band: Who was going to sit next to this black man in the close confines of the limo for hours on end? But there was no problem, because Bill instructed DeFord to sit with him in the backseat. Meals and accommodations would have been problematic in the South in that era, but Monroe brought food out to Bailey (who loved “that old ham sandwich,” an expensive treat at thirty-five cents when most other sandwiches cost a quarter).

After the shows, Monroe and other band members would have to find a hotel or rooming house that would accept a black man. Sometimes they were forced to walk around at three in the morning in the most unsavory neighborhoods until their quest was successful. In the dark, dressed in their riding pants and Stetsons, the Blue Grass Boys might have been mistaken for state troopers, but it was certainly the size and determined air of Bill Monroe that prevented any assaults.

Bailey was highly vulnerable in those strange towns, a diminutive man carrying large amounts of cash. So Monroe would make sure that DeFord had locked himself securely in his room. He wouldn’t open the door until Monroe personally returned in the daylight to bring him out.

This went on day after day, mile after mile, night after night, whenever they toured, Bill Monroe functioning as traveling companion, caterer, and bodyguard to DeFord Bailey.

One of Bill’s most popular comedians, in black- or whiteface, was discovered not on stage but on the diamond. David Akeman was playing on WLAP near Winchester, Kentucky, when Monroe hired him as a player for his barnstorming tent show baseball team.63 Akeman was a good pitcher and a reliable hitter, and Monroe apparently wasn’t even aware at first that he was a performer who played the banjo.

David Akeman had been born in Jackson County, Kentucky. Several greats of the old-time banjo came from there, including Buell Kaze, Lily May Ledford, and Marion Underwood. Akeman’s father, a corn and tobacco farmer, also played the instrument. David was a natural entertainer who grew into a tall, skinny young man and adopted the comedy stage persona of “Stringbean.”

Stringbean joined Bill full time in July 1942, first as a comedian, but soon as a banjo picker. Bill had enjoyed hearing the banjo in childhood: Uncle Pen’s friends Cletis Smith and Clarence Wilson had played the instrument.64 The Blue Grass Boys was now a fivesome.

The five-string banjo is the only widely played instrument to have been developed primarily in the United States.65 It descended from three-string West African gourd instruments brought to America during the slave trade. It was known by various names including the “merrywang.” (How far might it have gotten if a stage full of minstrels announced they were going to play with their merrywangs in public?) But it was best known as the “bajar,” “banjar,” and finally, the “banjo.”

As the banjo fully evolved in the nineteenth century, it gained four main strings and a high-tuned fifth string that ran about three-quarters of the length of the instrument’s neck. This was primarily used as a drone string and characterized the five-string “regular banjo” favored by rural musicians. The five-string was usually played by strumming the main strings with the fingernails and sounding the fifth string with the thumb (a technique known as “clawhammer,” from the shape the hand took, or “trailing”); alternatively, the strings were picked with the thumb and one or two fingers. (Tenor and plectrum banjos used in jazz and Dixieland had four strings and were strummed with a flat pick.)

The gourd had long since been replaced by a wood and metal drum with thin calfskin stretched across it and increasingly sophisticated systems of tone rings and resonators to improve sound quality and volume. Its bright sound and manageable dynamic range made it a great favorite for early recorded music. By the 1940s, though, the five-string banjo had largely become a prop for country comedians, having been displaced as a solo instrument by the fiddle. So for now Bill was only using, as he put it, “the touch of the banjo.”66 Soon, though, he was going to help make the five-string a star.

In 1942, a man arrived who would begin to truly define a distinctive bluegrass style of fiddling—a native of Tennessee named Howdy Forrester.

Howard Wilson Forrester was a nineteen-year-old playing in a San Antonio club on December 7, 1941, when word came of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Knowing that America would go immediately to war, Howard went to Nashville, where he had some family. But he was not drafted at once, and in early 1942, “Big Howdy” landed a job with Bill Monroe.

Tommy Magness and Art Wooten had been pioneers in the adaption of old-time fiddling to the demands of a new music where vocalization played an equal role with instrumental work. Now Forrester developed additional strategies for playing song melodies. His most common approach was to state the melody close to the way it was sung, but when the end of a line was reached—at the point where the singer would typically be holding a note or taking a breath to start a new line—he’d add a brief scale or arpeggio. This improvised string of notes would lead to the next major melody note.

Due to early wartime restrictions on recording, Howdy never got on disk with Monroe. But the Opry broadcasts were widely heard and Howdy Forrester became a highly influential fiddler.

Howdy’s draft notice came in early 1943. Monroe promised Forrester his job back when he returned.67 And as it turned out, Howdy’s wife, Goldie Sue Wilene Russell Forrester, was an excellent musician who played piano, guitar, and violin. It is not clear they ever played at the same time in the Blue Grass Boys, but by the time Howdy joined the navy, Wilene—rechristened “Sally Ann” by Monroe—had joined the group, the first of only two women to do so officially. Surprisingly, she also played accordion. A reed instrument was a departure for Bill, but he thought of his mother’s accordion playing and said yes.68 Her vamping chords enlivened the band’s already strutting rhythm, and she was an equally engaging vocalist.69

Mrs. Forrester also kept the band’s books during tours. She’d frequently find herself carrying thousands of dollars in cash, as her son Robert Forrester reports:

She would have two or three days of receipts built up. According to Mom, Bill didn’t want to be bothered with business. He trusted Momma implicitly, and left it to her. He didn’t look after business the way a Roy Acuff did. He was in the music business, but his emphasis was on the music.70

Of course, when Carolyn appeared there would be a lot of frantic business behind the scenes.

As Mom told me, at the time Bill married Carolyn, he could have married Bessie. Carolyn’s father was a preacher and Momma thought that perhaps Bill feared a preacher’s wrath if he didn’t marry her.

Bessie would be out on a show, and Carolyn would come around, and [Mom] would have to hide Bessie out. Bessie and Carolyn were at odds over Bill, but he also had other women on the side.

Bill was a very romantic person, but Momma also said that in all the years she worked with him, he never made an advance toward her. She said the same about all the guys in the band. They were always gentlemen and treated her with the utmost respect. They never used foul language around her. She said, “Bill always treated me just like I was his sister or a member of his family. He was always a perfect gentleman.”71

Of the many paradoxes of the man who was Bill Monroe, this is perhaps the most intriguing. He seemed incapable of fidelity to Carolyn, to Bessie, to any woman. He chased skirts so incessantly that colleagues joked that Bill Monroe had just two things on his mind—and one of them was music. Yet Bill observed definite boundaries. He firmly believed that married women should be off-limits. His code of honor extended to his musicians’ girlfriends, in stark contrast to many bandleaders who considered their sidemen’s women fair game. Bill Monroe’s gallant and respectful treatment of women already spoken for was a lifelong pattern.

On March 4, 1943, Bill and Carolyn paid $11,000 cash for a 44-acre farm on Dickerson Road.72 There they lived, according to George D. Hay, in “a very comfortable American home, the kind one reads about but seldom sees.”73 Sometime that year, Bill made another investment, modest in capital and profound in return.

It was in October 1943, as best as can be determined,74 that Bill was in Florida and, while wandering around after breakfast, happened to pass a barbershop and look in the window.

There, for sale, was a used mandolin. Monroe was looking for a second instrument, perhaps one to use for nonstandard tunings. He went in and played it.

The mandolin was a Gibson F-5 Master model, serial number 73987. A label glued inside the body, visible by peering through the lower sound hole, certified that this instrument had been tested and approved on July 9, 1923, by someone with the rather prosaic name of Lloyd Loan75

Bill purchased it, case included, for about $150.76 It was to become the most famous single instrument in country music history.

In the late nineteenth century, long after the mandolin had evolved in Europe from the lute, it enjoyed a new popularity in America.77 Mandolin and guitar combinations became the perfect complement for courting couples or merry campus music making. Mandolin orchestras became popular. Foremost in the reinvention of the mandolin was Orville Gibson of Michigan, who, by 1898, had totally redesigned the instrument. Instead of a round-backed, Neapolitan-style instrument, Gibson’s was larger and flat-backed, constructed more like a guitar for extra volume. Its body was highlighted by a hollow curled scroll that gave it some added acoustical properties as well as an Italianate appearance.

By 1921, as the Jazz Age dawned, the mandolin had been supplanted in popularity by the tenor banjo and the ukulele. The Gibson Guitar and Mandolin Company decided to boost mandolin sales by improving the instrument. A series of crucial refinements were made, most notably carving and tuning the tops in the manner of violins to improve tone and increase volume. The Gibson F-5 mandolins even had violin-style f-shaped sound holes.

Lloyd Loar was a concert master hired by Gibson in 1919, first as a demonstrator but later as an acoustic engineer. He worked with the engineering department on the development of the 5-series or “Master Model” instruments, including the L-5 guitar (which quickly became favored by jazz guitarists) and the F-5 mandolin.

During the four years Loar was supervising engineer at Gibson, 1921 through 1924, he approved and signed about 170 of the F-5 mandolins. (These instruments are now commonly referred to as “Lloyd Loars.”) They were notable for their fine woods, beautiful craftsmanship, superior tone, brilliant balance of sound throughout their ranges, and increased volume. In the hands of a skilled player, they could project notes clearly to the back of large concert halls. (When Bill worked with Charlie and during the first years of the Blue Grass Boys, he played a Gibson F-7, a good but much less expensive instrument.)

In the 1920s, brand-new Gibson F-5s retailed for $250 plus $25 for a hardshell, plush-lined case. The peg head of each was topped with the company’s name inlaid in flowing mother-of-pearl script: not simply Gibson, but “The Gibson.” But the F-5 was a commercial failure when first introduced. Musical tastes had changed dramatically. “It was like inventing the ultimate buggy whip after the invention of the automobile,” says Nashville-based instrument expert George Gruhn. “Nobody cared.”

It took a new use for the Gibson mandolin to reemerge. It was a long way from a classical musician performing a Vivaldi mandolin concerto to a country performer like Bill Monroe picking a hot breakdown on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry. But the Gibson mandolins were ideally suited for their new niche. In these days of rudimentary sound systems, a Lloyd Loar Gibson F-5 could be counted on to cut through an ensemble of fiddle, banjo, guitar, bass, and even accordion, and be heard.

This is a marvelous irony in American music history: None of the instruments that came to be used so effectively by bluegrass musicians—the fiddles built on the design of Stradivarius violins, the Gibson Master Model F-5 mandolins, the large-bodied Martin D-28 “dreadnought” guitars, the Gibson Mastertone RB-series banjos, the “three-quarter” bass fiddles—were ever designed to be played by country or folk performers. All were developed for classical or professional artists in orchestral or other concert hall situations. The instruments originally marketed to “hillbilly” or folk players, who had little money and usually entertained in intimate settings, were cheap products, often sold via mail-order catalogs. Only when the superior instruments temporarily fell out of fashion did they turn up where country people could find and afford them: in used instrument stores, pawnshops, newspaper ads—even in barbershop windows.

Bill treasured the way each note would sound “separate” on his Lloyd Loar F-5, ringing on its own. For a musician who valued the integrity of melodies and the shaping of each note, this was a fabulous quality. He would come to own others, but the July 9, 1923, Gibson Master Model F-5 serial number 73987 would forever be The Mandolin to Monroe and his fans, as inseparable from the man and his myth as Jim Bowie and his knife.

Indeed, this object was part reliable weapon, part work of art. Monroe carried it with masculine confidence, as if it were a meticulously crafted and perfectly balanced Remington 12-gauge shotgun or Colt .45 revolver. He unconsciously described it in such terms:

If you’re really in a tight spot, you’ve got a powerful crowd or a big auditorium, that mandolin will always come through for you. It’s got plenty of volume and it carries good and if you want to soften up, it’s got a beautiful tone. So it’s just perfect for what we use it for.78

Bill’s Lloyd Loar played a profound role in his music because it directly influenced his way of playing. Its quick response made him begin to play snappier arpeggios and cascade-quick triplets. Its ringing qualities caused him to use more individual notes in punctuated syncopations. Monroe commented again and again that in composing a new tune, one note he played on his mandolin would suggest or lead into another note. All the F-5s signed by Lloyd Loar in this period are wonderful instruments, but this instrument had exceptional tone and sustain, a sound that was clean yet woody, sharp yet resonant, seemingly with a halo around each vibration.

On February 13, 1945, Bill raised his F-5 to a recording microphone in a studio in Chicago’s Wrigley Building79 and hit the first jaunty notes of his introduction to “Rocky Road Blues,” a jazzed-up twelve-bar blues. He not only had a new mandolin and a new band, he had a new label—Columbia Records. Charlie was still on Victor, and Bill decided to differentiate himself from the other half of the Monroe Brothers act once and for all.80

At the time, Art Satherley was Columbia’s A&R man (“artist and repertoire,” reflecting the twin responsibilities of talent handling and overall producing). Satherley was a self-assured, impeccably mannered British gentleman,81 and many of his country artists were in awe of him. But in the studio his blend of perfectionism and politeness allowed him to get excellent performances out of his charges, and Bill was no exception.

It was the first session for Chubby Wise, Howdy Forrester’s replacement. Wise, a Florida fiddle whiz who had popularized “Orange Blossom Special,” built on Forrester’s work and brought his own genius to the Blue Grass Boys. He could be soulful and spirited, yet his bowing was smooth, his tone sweet. He could really hang on to a note and make it sing. Indeed, he was like a singer with his fiddle.

James Buchanan Monroe, Bill’s father (Country Music Foundation)

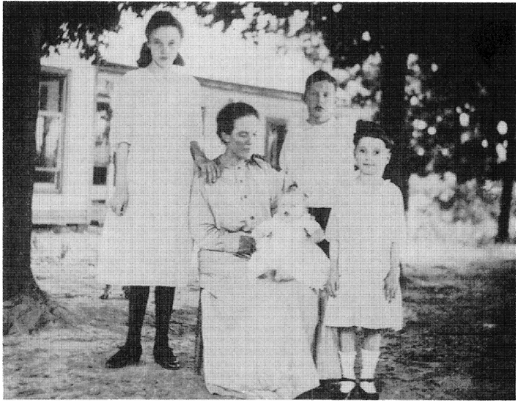

Malissa Vandiver Monroe by the new farmhouse with two grandchildren and, behind her, Bertha and Bill, circa 1920 (Country Music Foundation)

Pendleton Vandiver, Bill’s beloved “Uncle Pen” (courtesy Sara McNulty Crowder and Bluegrass Unlimited)

Arnold Shultz, left, with Rosine resident Clarence Wilson (courtesy John Edwards Memorial Foundation)

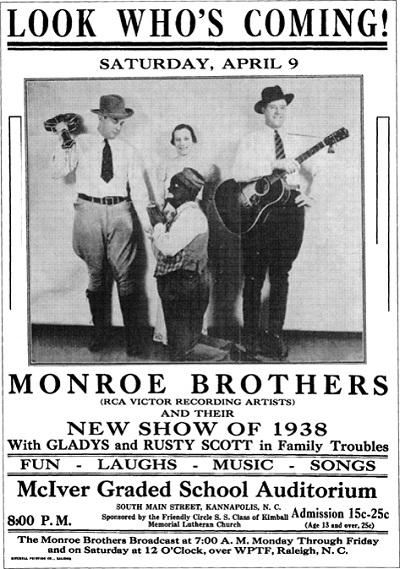

Show poster of the Monroe Brothers with comedians Gladys and Rusty Scott. Bill’s treatment of real African Americans was much different (Bluegrass Unlimited)

Carolyn, Bill, and Melissa, late 1936 or early 1937 (Bluegrass Star, courtesy Bluegrass Unlimited)

The original Blue Grass Boys, 1939: Art Wooten, Bill Monroe, Cleo Davis, and Amos Garen (Bluegrass Unlimited)

Tent show music and baseball barnstormers Howard Watts, Chubby Wise, Dave “Stringbean” Akeman, Clyde Moody, and Bill Monroe (Bluegrass Unlimited)

Bill with Chubby Wise, Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and Birch Monroe in the band’s speedy, high-profile stretch limo, circa 1947 (Bluegrass Unlimited)

First despised imitators, later Bill’s treasured friends: Ralph and Carter, the Stanley Brothers fBluegrass Unlimited)

Monroe and Jimmy Martin bring their “high lonesome” sound to a quartet at the Ryman Auditorium with Charlie Cline and Jim Smoak (hidden) plus Buddy Killen and son Slocum (Grannis Photo)

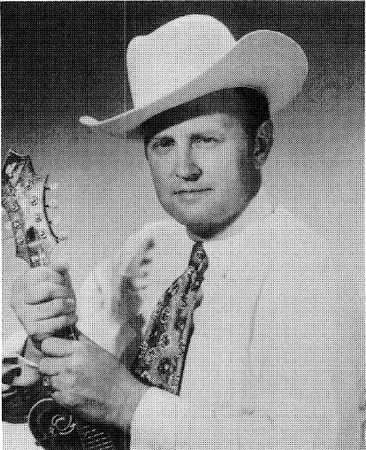

The handsome, confident country music star: studio portrait, circa 1951 (courtesy Douglas B. Green)

In traction after his near-fatal wreck, Bill receives benefit concert money from Carl Smith, Eddie Hill, Opry director Jim Denny and stage manager Vito Pellettieri, Roy Acuff, and Ernest Tubb (Country Music Foundation)

Former sidemen, now polished showmen: Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs, late 1950s (Les Leverett/WSMO)

The spark and sparkle that kept them together: Bill Monroe and Bessie Lee Mauldin (courtesy Bill Price)

The band’s beat was slightly different now, still crisp but with more of a bounce than a surge. The Blue Grass Boys of this period sounded closer to a western swing outfit than a square dance band, in part due to Sally Ann Forrester’s rhythm vamps on the accordion. Another factor was the lack of bite in the banjo picking of Stringbean, whose greater strengths lay in his comedy. But the sound perfectly suited the material, which included “Kentucky Waltz,” a wistfully sentimental vocal credited to Monroe as composer, as well as the strutting “Rocky Road Blues.”82

Bill sang with rousing defiance about how the road wouldn’t be rocky for long even though another man had taken his woman and gone. And that—the unthinkable—was precisely what had happened.

Bessie Lee Mauldin had left him for another man. Their relationship would cause Bill Monroe to write some of the most searing, agonized, and wonderful music of his life.

Nelson Campbell Gann was born in Lebanon, Tennessee, in Wilson County, east of Nashville, on September 22, 1921.83 Although Gann was ten years younger than Monroe, the similarities in the backgrounds of these rivals are amazing.

Both came from farming families. Arthur W. Gann, Nelson’s father, was a cattle dealer. Like Bill, Nelson was a youngest child, having three older sisters and a brother. The year before Nelson’s birth, the 1920 census also found that living at the Gann farm were two boarders and (shades of Uncle Pen) Arthur’s brother-in-law.

Astrology devotees will no doubt notice that both men were Virgos. But of truer developmental significance is that both were born to middle-aged parents (Arthur and his wife Sula Jones Gann were forty-three at Nelson’s birth) and that both lost parents while young (Sula dying in 1925, when Nelson was four; her headstone records that she was the widow of A. W. Gann, indicating that Nelson lost his father even before his mother).

Who raised Nelson is unknown. His oldest sister was only about twenty at the time of their mother’s death. But it appears that when he turned eighteen, he left Lebanon and headed for Nashville, much as Bill had left Rosine and moved to greater Chicago. Nelson did not find work in a factory or refinery, however; he appears to be the same Nelson Gann listed in the 1940 city directory as working as a clerk at Foxall Moon Drug Company, a pharmacy with three Nashville locations.

Also unknown is how Nelson and Bessie Lee met.84 But if Bessie was already experiencing the illnesses (including heart problems and diabetes) that would plague her later in life, she might have been a customer at the drugstore where Gann was employed.

Nelson Gann was handsome and dashing, every inch a man.85 During World War II, he served in the navy as a petty officer and by 1943 or 1944 was stationed in Piedmont, California.86 Bessie Lee soon joined him on the West Coast, because by now they were married. She must have known that Bill was not about to leave his wife and children, and she must have also known that he had other women. She had every reason to take up with Gann.

Bill, of course, had a personal rule about not fooling around with married women. But in this case, the rule had its exception. Bill Monroe believed—deeply, fiercely—that Bessie Lee Mauldin was his. And always would be.

Betrayal. A love that has proven untrue. A man left blue and alone.

Bill was on tour, driving back up from Florida, when he saw a particularly large full moon over the highway.87 It reminded him of the moons he had seen in Kentucky, and he wanted to write about it. The best poetic device, he decided, was to bring a girl into the song. It will never be known if Bill was thinking about Bessie or any actual woman, but thus was born his most famous composition, “Blue Moon of Kentucky.” This wistful waltz, its lyrics full of sad resignation as the singer calls on the moon to shine upon his false lover, would of course have a second rising thanks to the young Elvis Presley’s first commercial recording.

The song’s metaphor was perfect, more so than Bill realized. When two full moons appear within the same month, the second is called a “blue moon.” This infrequent event gave rise to the expression “once in a blue moon.” Of course, the second moon does not actually have a bluish tinge. “Blue” probably comes from the Old English word “belewe” meaning “to betray,” reflecting the ancient belief that rare astronomical events are inauspicious.88 Monroe knew nothing of this, making his choice of a blue moon for a song about betrayal even more striking.

Fiddler Jimmy Shumate had been playing over WHKY in Hickory, North Carolina, on a noontime show with Dan Walker & the Blue Ridge Boys. One day in late 1944, the phone rang at his family’s farm. It was Bill Monroe. Howdy Forrester was still in the navy and Chubby Wise had temporarily left the Blue Grass Boys.

“Your style would fit mine,” Monroe said.89 “I’d like you to come play on the Grand Ole Opry.” Shumate accepted with alacrity, but then wondered: How in the world did Monroe know about me?

Numerous musicians, flattered but curious, would ask themselves the same question in the years ahead. Shumate learned this: During Monroe’s hundreds of days of touring each year, the radio in the Blue Grass Special was often kept playing. While his sidemen simply enjoyed the diverting music being broadcast live from stations across the South, Monroe was in the backseat, listening attentively and discerningly, quietly filing away in his mind pickers, fiddlers, and singers, their names and locations, their styles, strengths, and weaknesses. When he needed a new band member, he would simply call a station, introduce himself, and get the appropriate musician’s home phone number.