CHAPTER 9 A MINIMUM VIABLE PARTNERSHIP

You’ve probably heard plenty of tech-startups talk about their ‘MVP’; their Minimum Viable Product. Sometimes, the term is misused to present a product that isn’t finished or doesn’t work. Used correctly, it is used to talk about a product in a specific stage of development. Let’s say you have an idea and you want to test it, how do you find out as fast as possible if it’s a win or a fail? Well, you define what the minimum features are to prove your solution works, and then you start testing.

Say, for example, you invented a wireless keyboard. You want to solve the problem of the mess of cables on your desk, or the mismatch between different brands of computers, screens, keyboards and all the plugging that comes with hooking them up. To prove your wireless solution is feasible, you don’t need a key for every letter of the alphabet in your first version. Neither do you need a silky-smooth design. You need a basic test version with one button, no wires, and a Bluetooth connection. That’s it. Because one button and a working connection is enough to know if it’s a Yay or Nay.

This approach of defining the core functionalities and testing them before you add the glitter, the whistles and the bells will save you an immense amount of time, money and probably a sizable amount of frustration. We suggest this very same approach when starting your journey towards forming a metasystem.

Sadly, one button and a Bluetooth connection won’t suffice here, but we’ve mapped out what an MVP might be made of when speaking of partnerships instead of products. You will set up this Minimum Viable Partnership together with the other members of your soon-to-be metasystem and it is focused at developing and testing your trust system. Look at it as an attempt to prove whether or not the people assembled around the table are an actual match before you start investing heaps of money and time. Before going all in, let’s find out how you can make a smaller up-front investment to test if the lot of you can form a healthy metasystem.

INTERVIEW

THINK FRUGAL, BE FLEXIBLE

AN INTERVIEW WITH CHRIS BURGGRAEVE, FORMER CMO AB INBEV, ENTREPRENEUR, INVESTOR AND AUTHOR

We had the pleasure to speak to Chris Burggraeve, former CMO of AB InBev, a fellow Belgian living in New York. Chris has a long-standing career in big corporations, but is also an entrepreneur and active investor who has experience in building things from the ground up. In 2018 he published his first book, “Marketing IS Finance IS Business”, which we highly recommend. We were curious to hear if Chris believes that big companies could and should look at partnerships and metasystems.

Start from the hunger model

Chris: “Scoping what you want to achieve with your partnership strategy, and how you approach it, is very important. As they say, don’t try to boil the ocean. Define what specific problem you are trying to solve before committing too many resources. Try to start small. Always think as a bootstrapping entrepreneur. I believe in ‘the hunger model’: what if you had no money and limited time, how would you approach your partnerships and ecosystem? Don’t send out all the troops immediately and see things too big from the start, even as a big organization. Think frugal (which is not the same as cheap!) and be flexible.”

Purpose and sustainable pricing power go hand in hand

Purpose and sustainable pricing power are two crucial instruments for a brand-based business to stay successful in this era. As a business leader thinking about partnerships, I would ask myself the question: how can I further build the purpose and sustainable pricing power of my brand(s) by going in alliances with others? Choosing the B Corps structure could be an excellent legal commitment of making that combination of purpose and pricing power in a networked model. Joining the UN Global Compact is another good example of fulfilling both conditions and creating a collaborative spirit around those ambitions.

“Partnerships can be a very clever way to create scale for your ideas. Enlightened self-interest is a great driver.”

You have to make your alliances visible

Partnerships can’t just live in your own head or your internal operations. If partnerships only happen in the backend and they have no true impact on behavior or perception of your customer (or stakeholder), then you need to ask yourself why you’re actually doing it. If it’s just a warm feeling but nobody notices, then you’re missing out on the real opportunity.

“Partnerships don’t just accelerate the company, they broaden the horizon of the senior leadership.”

If you stay in your own bubble because you’re successful and you believe you know everything yourself, then you can’t fully imagine what you can achieve. Building partnerships is not just good for the company in itself, but also for its senior executives. It broadens their perspectives and growth mindset. The higher you go up in the organization the more humble you need to become about what you can do as a single individual. I used to be the President of the WFA (World Federation of Advertisers). Our slogan was inspired by Kenneth H. Blanchard: “None of us is as smart as all of us”. I believe that to be true more than ever in this complex world.

CHRIS’ TIPS:

•Start from the hunger model, don’t go big immediately.

•Make your partnerships visible to the customer or stakeholders.

•Even if you are very successful, partnerships will broaden your horizon.

Trust system. What is it? How does it work?

Your trust system can be defined as the composing elements of trust and the way to analyze, build and grow healthy levels of trust.

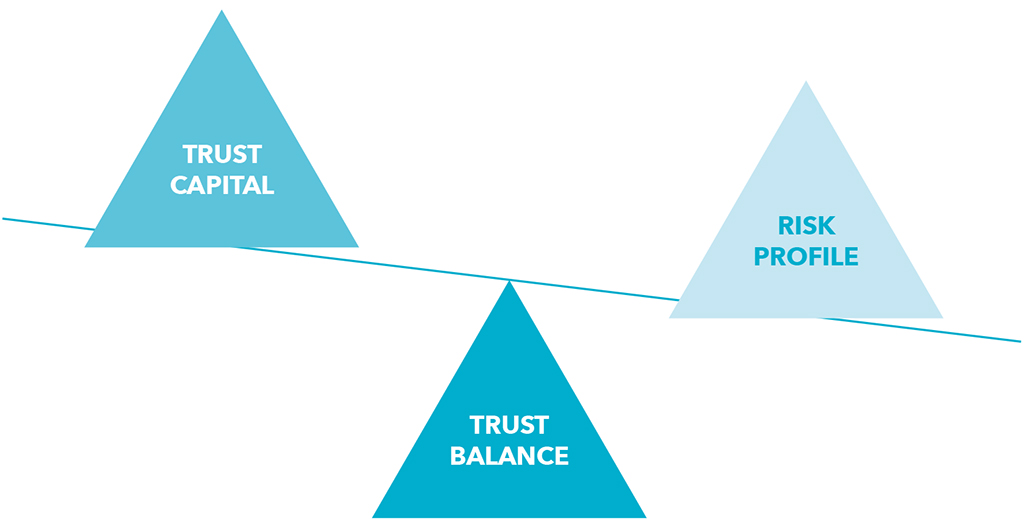

Trust capital

Your trust capital consists of all the elements that make you trustworthy. Unlike in a pilot-passenger relationship, business relationships call for reciprocity. So, to engage in a partnership based on trust, you need to have built your trust capital in the past. This is a life-time job which requires careful sowing, harvesting and foresting. Trust might be ungraspable as a concept, but that shouldn’t keep you from actively growing your capital.

Consistency is desirable in order to be trustworthy in the eyes of a potential partner. No matter whether your business is having a good day or bad one, your partner will require the same version of you at the table time and time again. Your partners need to be able to count on you. They want their expectations to be met. Things to keep in mind for a consistent image when engaging with others: be unambiguous, predictable and direct. Having a good reputation doesn’t come for free. The easiest way to build a sound reputation is to deliver the results you’ve promised to achieve. Don’t bluff – someone might call you on it.

Your trust capital in business is linked to your company or your team. However trustworthy you are, if this doesn’t translate to the rest of your company, colleagues or actions, it’s no good. In order for the whole to be trustworthy, you need common values and a common purpose. While every person uses what talents they have, all eyes are on the same price. This shared purpose will give your company a clear voice towards the outside world, making it easier to be trusted. You will have to set up a symbiosis of individuals, teams and the company to carry out that trust capital.

Risk profile

While we want to focus on the importance and makeability of trust, it’s important not to neglect the risks, as being naive would certainly diminish your chances for a sustainable and trustworthy partnership. To put it plainly: working together with other companies comes with a potential cost of failure. And while the worst that can happen nearly never happens, it does sometimes happen, which feeds a feeling of unsafety and makes us exaggerate the probability of that risk. As a result, this fear of risks may break your trust.

Thus, the second dimension of trust building we want to elaborate on is that of risks and rewards. Building a good partnership means being aware of potential risks and building in healthy incentives so everyone will play by the rules. Like the Story of the Commons taught us, people are fickle creatures sometimes. Neither are we extremely benevolent or always inclined to put our own interests before those of the community. That’s no drama, though. You just have to find a way to work around your flaws, rather than ignore them. That way, you can counter the risks before they arise.

To dramatically decrease the odds of things going wrong, dare to think forward and take time to imagine the worst that could happen. Look for faults in your own company, in that of the potential partner, and in the plans you’re making. You can have the brightest ideas and plans, but the foundations have to be healthy. Whatever plans you put on the table together, they have to be financially, technically and operationally feasible. That’s a no-brainer. A bit harder to foresee are the more strategic risks. What future plans or movements might generate unwanted friction? Are there possible conflicts of interest? What is the exit strategy for all involved? And if something does go wrong, what is the potential damage to your reputation – that same reputation that doubles as your trust currency.

The success of a partnership depends on the size of the price. The efforts, time and resources to build a metasystem are substantial, so should be the reward. We don’t only mean financial rewards but also societal impact. The Story of the Commons explains the dynamics of incentives and rewards as a way to bypass certain risks. One way to make sure the people involved feel they have skin in the game is to factor in an upfront investment, be it financially, in time or based on other resources. You might even want to build in some short-term rewards, seen as the relationships last long and you don’t want to overstretch people’s patience.

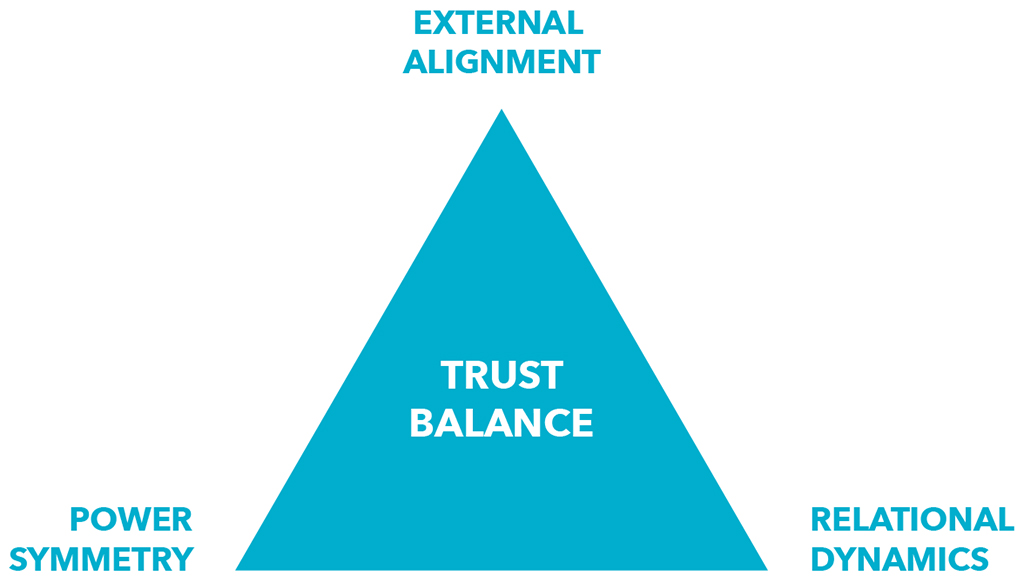

Trust balance

Your trust capital is built in the past, the risk profile is a consequence of the metasystem opportunity. Next step is to understand the art of balancing, the dynamics that we call the trust balance: a framework you and your partners need to construct and agree on, in order to create a long-term, sustainable collaboration.

The most important reason for needing such a system is to make sure all partners around the table are equal. A trust balance is the equivalent of a handicap in golf: it levels the playing field so that a beginner can take on a pro and both might have an enjoyable afternoon.

This co-created system – or mutually agreed upon handicap – will create a context where trust can safely flourish in parallel with your partnership. Keep in mind you are building a dynamic culture of trust, with clearly defined rules and clearly defined wiggle room, allowing for your relationship to evolve along with the ever-changing context.

External alignment

Before placing that ball on your tee, you’ll need to agree that you’re both aiming for the same distant red flag. While there is a long list of possible wins in a partnership, you will need to decide which one to focus on, as not all of them are relevant for every partnership. Will you focus on the fruitful insights distilled out of your shared datasets, the innovative new propositions that arise when you combine your products and services, or the beneficial impact you can have on the planet when combining your efforts to shrink your footprint? Find out where the network effects might work its magic for your collaboration.

Power symmetry

Another issue to consider before signing off on your big plans is how you’ll distribute the power so everyone has just as much of a say. An imbalance in power is no basis for trust or collaboration. You’ll have to construct a frame where the obvious differences in size or capital are evened out. As an example, splitting costs fifty-fifty might seem fair at first sight, but creates a big unbalance when the financial means of the partners vastly differ. The same goes for negotiation power: the little guys wouldn’t really have a say at the table unless they are explicitly given a voice. And if you really intend on collaborating, you probably don’t want a mute at the other side of the table. In other words: let the broadest shoulders carry the most weight.

Relational dynamics

Interdependence between parties is like a very intricately woven fabric, which makes it hard to say what will move if you pull this or that string. The longer the relationship, the more intertwined the threads. This means that managing the relationship between all the partners, formal and informal, is paramount. How will we organize governance? How do we keep all communication lines open? How do we create sufficient informal moments? How do we party and celebrate? Acknowledge that just like any relationship you will have to put in the work, make time, understand each other’s language.

Trust by design

Trust is the conditio sine qua non for partnerships. Attaining trust is no easy feat, yet it becomes easier the more parties you have around the table. At least, up to a certain point it does. While more parties increase the complexity of governance, the power among them is automatically more evenly distributed, diminishing the chances of a show-off or one-on-one powerplay. The peer pressure in a bigger group assuages the egos a little, which allows more room for trust.

Scale offers certain benefits. It balances the egos, for one. But seeing as personal contact is a key ingredient for trust, there is a stage where size can become counterproductive. There is no exact science and there are no precise numbers you can use, but your common sense and the facts on the ground: you are out of chairs; the next time everybody can free their schedule is in 2030; you keep on forgetting people’s names so you have to call them sir or madam, which is oddly polite for the context.

Furthermore, the search for complementarity is more successful when different parties step up to fulfill a broad specter of needs and offer a heterogenous skillset. Together, they are better prepared to tackle a wider variety of challenges. In conclusion: whether it’s responsibility, investment, skills, risk and even data, all these things are better when shared in a network constellation. That makes ‘distribution’ the magic word in multi-partnerships.