CHAPTER 12 THE POWER OF PURPOSE

Growth is progress, and progress is the real profit. That sums up the case made by Jim Collins and Jerry Porras, who published “Built to Last” in 1994. The book outlines the results of a six-year research project exploring what leads to enduringly great companies. Both gentlemen combed through data from a group of companies they said were ‘visionary’. Having analyzed information gathered from 1926 to 1990, they found that companies who built their businesses from their ‘core ideology’ often ended up in the famed Fortune 500 list. What they also found is that purpose-driven companies make more money than their competitors – isn’t it ironic?

We are not here to hand you ways to make more money. Neither are we here to tell you that profit is the devil. It is not, and in order to keep your company a healthy one, you will definitely need it. However necessary profit may be for your company’s existence, it’s not the only thing you’ll need. The research done by Collins and Porras shows that following a clearly defined purpose pays off in more ways than one. A purpose helps you create a positive societal impact, like keeping into mind your carbon footprint when making packaging decisions.

Having the world at large at the back of their mind when making decisions makes companies more cautious and less callous. Just like MUD Jeans, who turned mankind’s favorite piece of clothing into a renewable resource. At MUD, you don’t buy jeans, you lease them like you would a car. When your lease is up, the jeans go into the shredder to be made into new jeans, and you get a fresh new pair to wear. Consciousness of the environment and the community drives these companies to rethink their business model.

In the past years, purpose has become one of the most used words in business. Nothing wrong with that. But be aware it has many different meanings. Many companies have taken to rebaptizing their business goals, but just naming them ‘purposes’ instead of goals doesn’t mean a company is actually purpose-driven. Saying you aim to be “the number 1 company in the world” or “ the best consultant in the world” is a goal, not a beyond-profit purpose.

A good purpose has three qualities:

•It is internally relevant and authentic, built on the historical root strengths of the company.

•It is inspiring and ambitious, both internally and externally.

•It allows others (partners, consumers, government, NGOs) to join and support your cause.

The latter is a big one, for a good purpose reaches beyond the walls of a company. Having a purpose helps to define success (are you moving in the direction of your zero-emission goal?) and it helps to measure it (how many tons of CO2 has your product saved the world from?). Your purpose will guide you toward taking appropriate decisions in any given situation. Having a purpose, allows you to collaborate to form a coalition of the willing, like we saw in the Partnership Pyramid.

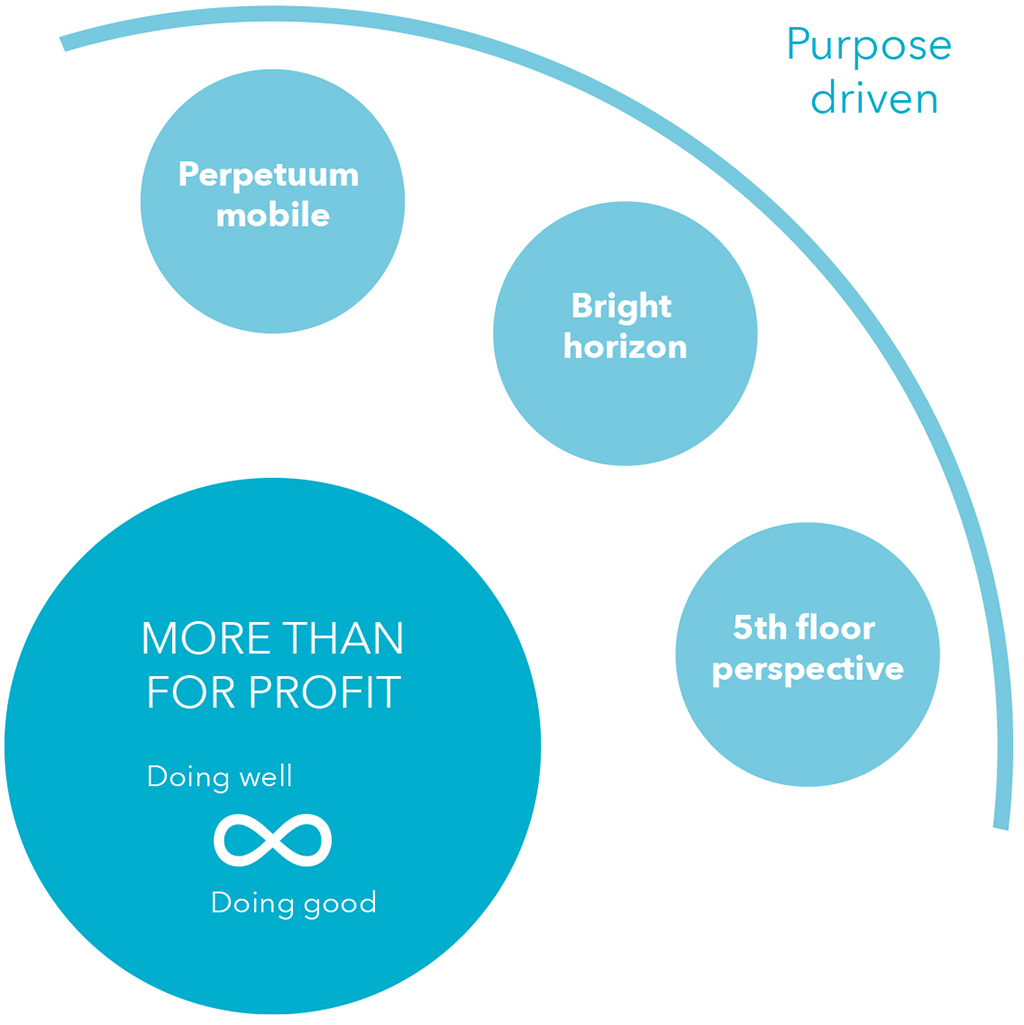

There are clues we can take from how a handful of pioneers run their business the beyond-profit way. Likewise, we might learn from these visionaries’ way of taking a step back to have a better understanding of what’s out there. If you pause to look further than the imminent threats and adopt a different perspective, you’ll be much more confident in making the right choices. In the end, your purpose will serve as the ultimate compass to run your company first, and to find the right partners for your metasystem next. With this purpose at the back of your mind, you’ll never be confused about which direction ‘good’ is.

The bright horizon

First things first. (Rolling up sleeves.) While all nine dimensions of the wheel are of equal weight, we did choose to talk about positive societal impact first, because it’s not just one of the things you’re working on, it’s what keeps you going. It’s why you do what you do. Or at least, it should be.

As a company, your goal should lie beyond the profit. And while The Nine are all tied to this notion, this one spells it right out. Your bright horizon is your goal to create a positive societal impact, one that takes you beyond your duties to your employees and investors. It requires you to think about how your actions impact the world at large. It asks you to reflect on what you do and why you do it. Not just on what you produce, but how you run your business as a whole.

Why outrunning the law is a good idea

The law creates a framework for companies to operate in. However, you may ask yourself whether just following the law isn’t setting the bar a bit low. In most countries, for instance, companies do not have to pay any fees to make up for the CO2 they release into the air. Hence, their emission is legal. It doesn’t make it desirable, though. While you could argue it is fine to emit greenhouse gases as there is no law against it, we’d like to counter by saying the law doesn’t forbid you to be ambitious, either. In cases like this, you’d do well to regard legislation as the Olympic minimum.

There is no need to be minimalistic. On the contrary. It’s up to you to do better, to be at the forefront of a fight for the better, to go beyond yourself. By nature, laws are slow. Don’t wait for them to lead the way, they can only be passed after the fact. You, however, have the leisure of running a company and staying ahead of the curb, predicting trends and plotting for the future. Use this advantage for the greater good – which, incidentally, is also your own.

With the right proportions, anything goes

Of course, it is hard to calculate how big an effort you should make to mean something for the community. Let’s try anyway.

The principle of proportionality is a big word for a simple idea. It says that the responsibility you hold should be in proportion to the impact you have. Say you’re enjoying your pension, tending to your garden and enjoying a game of cards now and then, then your decisions aren’t all that weighty. While we’d advise going easy on the barbecue meat, the amount of damage you can cause is rather small. If, however, you run a multi-billion company with units all over the globe, an immense logistics network and thousands of people working for you, we highly recommend you uphold values that respect the common good and run your company accordingly.

There is a direct link between power, responsibility and impact. The more power you have, the bigger your impact, the larger the weight on your shoulders to make it a positive one. If you don’t have any power, your responsibilities will be more basic, like taking care of yourself, your family, your house… Your impact is in proportion to the amount of people you are accountable for. “With great power comes great responsibility.” You’ve heard that one before. It was probably your mom who used to say that. Well. She was right. Moms usually are.

When joining forces in a partnership, a metasystem becomes more impactful than each of its individual partners and thus gains a higher level of responsibility. It’s the story of the sum and the whole and how the first one is bigger than the latter. While this isn’t necessarily a comfortable thought, it can be fruitful to keep in mind when forging alliances. Because together, you are also more capable of taking on a proportional responsibility for the impact you have, as there are simply more shoulders to distribute the weight.

The perpetuum mobile

The Honest Company, Patagonia, Veja, Tony’s Chocolonely, Flow Hive, Death to the Stock Photo, Chipotle. If you haven’t heard of them, look them up and find out for yourself that their strength lies in looking beyond the scope of their own business. These are companies who understand that caring is a competitive advantage. That it is a significant differentiator as people today realize that ethics matter and they expect companies to act accordingly. These companies know that their sustainable business models are the eternal source of power that keeps their perpetuum mobile going. On and on and on.

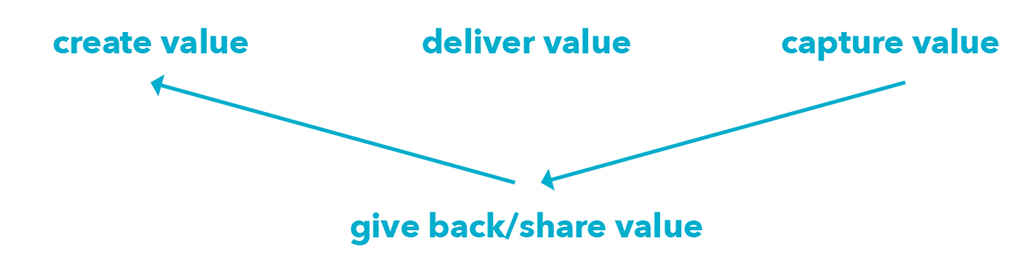

The traditional definition of business models consists of three components: creating value, delivering value and capturing value. In “more than for profit” business models we add the “give back or share value” component.

“MORE THAN FOR PROFIT” BUSINESS MODEL

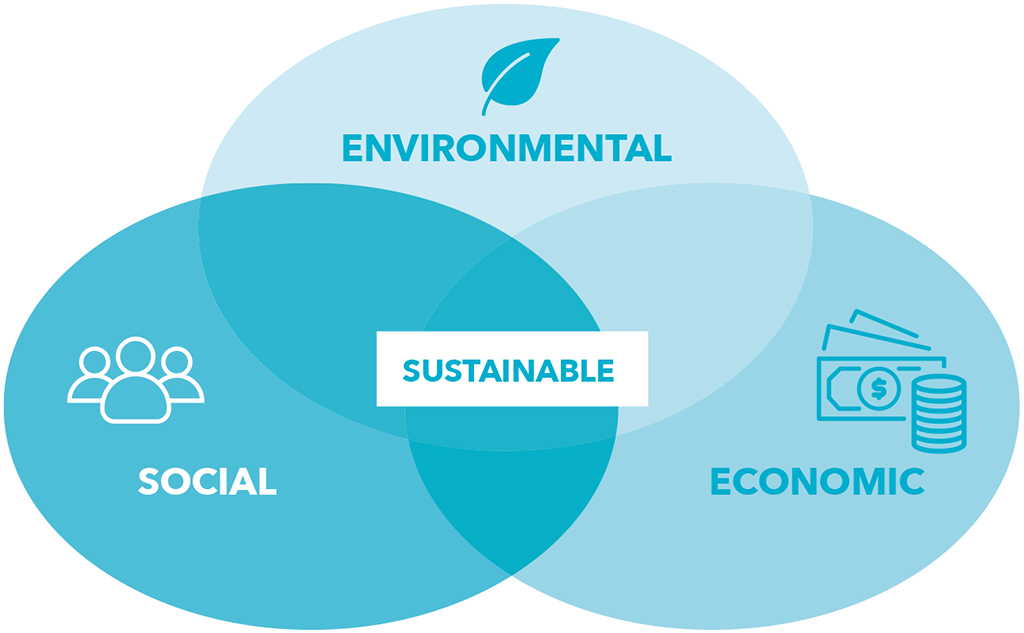

The sustainable love triangle

The realization that running your business the responsible way can help you grow is the basis for any sustainable business. The latter follow certain convictions that lead them to create an added value for their customers. Beyond-profit businesses go even further than to pursue their beliefs; they involve their customers in them. They gain in strength because they add value for their customers while continuously working on their mutual relationship. These customers, in turn, become ambassadors for their cause, loyal foot soldiers whose aim is to further distribute that value among their network. Win, win, win.

However, different companies have different ways of going at it. The big picture shows us the cookie is split three ways. Companies that are stamped as “sustainable” exist in the crossover between:

•creating a positive societal impact that is as large as possible (gender equity, fair trade, animal wellbeing,…);

•keeping their environmental footprint as small as possible (carbon neutral, zero waste, protecting the oceans,…); and

•rethinking the economic model (smallhold local farming, switching towards a sharing economy,…).

All of them put together will debunk the idea that sustainability is merely about “going green”. Pick any future-proof company and you’ll see that it has not been cherry picking. All components matter. It is about taking a broadly defined responsibility, not about trying to excel on all 17 sustainable development goals.

The triangle of sustainability and sustainable business models

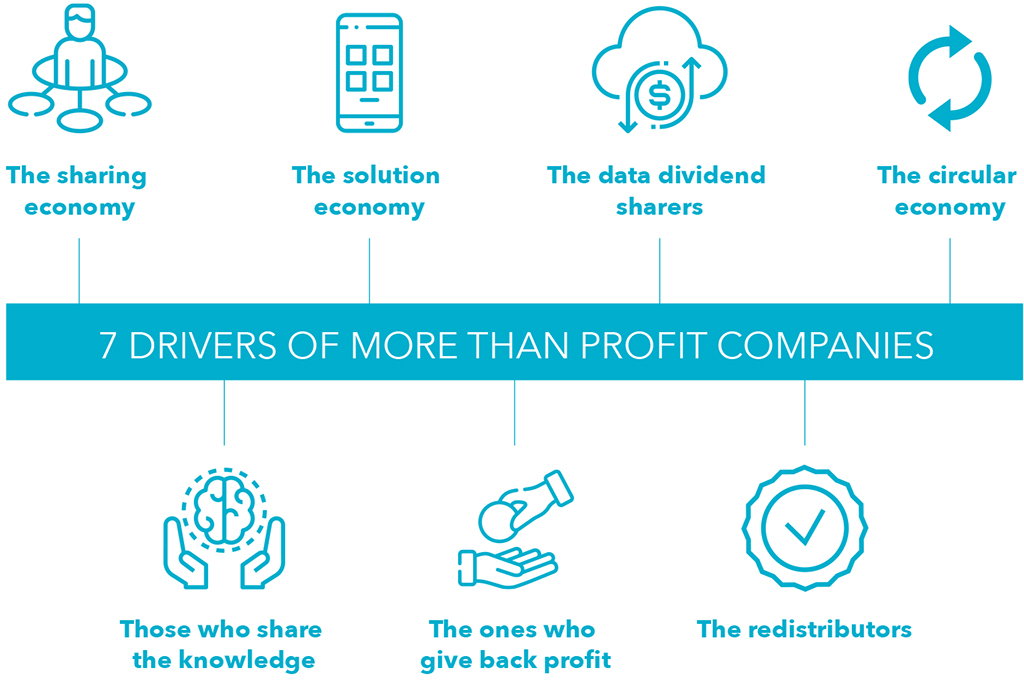

Seven drivers of more than for profit companies

In the way that more than for profit companies go about their business, there are more than three options. We’ve selected seven layouts used by companies with the characteristics of future sustainable titans. These are the companies that have proven creative, eager to build something that lasts and ready to take on whatever may come, shifting their weight from one foot to another like Muhammed Ali on boxing day. Use these models for inspiration, but remember that the purpose of your company will define its shape, not the other way around.

The solution economy

The solution economy centers around more personalized offerings that put the customer first, all the while adding a dimension of sustainability by switching to long-term thinking. For example, most internet providers have stopped selling decoders. They now offer you an internet connection with enough bandwidth to binge on Netflix for days on end. Likewise, Marley Spoon now offers fresh produce and neatly typed-up recipes right to your doorstep leaving supermarkets to scratch their weary heads. In the same category, Whim and Citymapper join information from many transport companies and show you the quickest way to your rendez vous by bike, car, Lyft, electric scooter, metro or whatever else is out there.

Their power lies in the combination of several tools, all rolled into one service. Rather than sell products, these solution-oriented companies have shifted their focus to offering services. The “As a Service” industry (AaS for short) takes its cues from software companies who have switched to offering everything from mobility to health as a service. This approach redefines their way of looking at what they put on the market.

Ever since Signify, a Dutch light bulb manufacturer formerly known as Philips, started seeing light as a service, it has become much more important for them to manufacture lighting solutions that last as long as possible, while in the past, they’d be quite content to offer you one that would have to be replaced every few years, a hint of planned obsolescence to ensure their recurring revenue. The recurring revenue idea hasn’t been thrown overboard, though: many of these companies offer subscriptions to their products and services. This system offers companies the advantage of a steady cash flow and customers a better, longer-lasting product.

The circular economy

Roman writer Ovid wrote that “Everything changes, nothing dies”. Many centuries later, he’d be proved right by physics experts, who agree that no matter is ever lost, nor created. In this respect, the circular economy is another example of biomimicry, as it takes nature as a leading example and reuses materials, preferably ad infinitum. In this closed loop, raw materials, components and products lose as little value as possible so as to maximize their lifecycle and minimize their ecological footprint.

Patagonia counts as an oft-cited example, sending out repair vans to all four corners of the US to mend their customer’s lovingly worn outdoor favorites. Loop takes a similar route, top brands ranging from Häagen-Dazs, over Gillette, to Dove offering packaging options which can be returned and refilled, time after time. This way, they haven’t only innovated with smart ways of packaging, but they’ve shifted the model altogether, turning producers into packaging owners.

Such smart moves are often inspired by a deep-rooted knowledge of technology, but have the advantage of solving a problem experienced by many other companies. Building a closed loop doesn’t just work for one business, but provides a possible solution for a whole industry, or an entire metasystem.

The sharing economy

You know this one. It’s brilliant because it’s as simple as a few neighbors sharing a lawnmower. The costs remain low, as they buy just one for the whole street instead. Plus, the investment is being put to good use instead of spending most days in a garage. And while it used to be just one person benefiting from one lawnmower, now there are thirty people with neatly mown lawns. In this case, less is definitely more.

From Airbnb to Uber, there are myriad companies who facilitate ways to share products, assets, property and more. Shifting the focus from buying to renting, services like Grover (rent technology), Peerby (rent your neighbor’s jackhammer) and Rent The Runway (rent a ballgown) have lessened society’s need to own and manufacturers’ response to produce more things we only use every once in a while.

The biggest perk of this model is these companies don’t own the things they are selling. They are making their initial investment much lower than their classically-run counterparts who have invested in hotel chains and car fleets.

However, it’s important to notice that many of the current “sharing economy” examples have toxic elements as they are often operated as “walled garden ecosystems” where one player on top of the food chain controls the data and the majority of the profits. We believe that for the sharing economy to be really successful, it should be ignited in the metasystem mindset with equal partnerships and a true “more than for profit” horizon.

The redistributors

The idea of these businesses is to redistribute the wealth; a decision usually fueled by ethical reasons. Soy drinks producer Alpro, for one, is part of the Rainforest Alliance, which pledges to use only products which are grown and harvested on farms and in forests following sustainable practices. This seal of approval is awarded to businesses that meet rigorous environmental and social standards. Many corporate companies brandish similar certificates: Nestlé is part of the Fair Labor Association, C&A boasts a membership of the Sustainable Apparel Coalition and ArmedAngels’ fair and organic fashion is approved by the Global Organic Textile Standard.

These widely known labels offer customers a sense of certainty of where and how their purchases have been manufactured. In these businesses, the focus lies on making sure everyone in the value chain is paid a fair price for their labor and efforts. This model can also work as a powerful tool to position your brand in the market, build a strong image and work on a story that’s an added value rather than an empty marketing phrase. A great example is Tony’s Chocolonely, who are on a quest to make not only theirs, but all chocolate slave-free.

These labels often set the bar of their standards high. This means you’ll have to go through the motions to earn their approval. On the other hand, you’ll benefit from the fact that they’ve already done all the thinking for you and just need to follow their rules, not write the playbook. They also make it very easy for consumers to cause no harm by consuming, opening the road to guilt-free chocolate highs.

The ones who give back profit

The give back profit model looks a lot like charity. Companies make a promise to give back part of their profit to a good cause. Think NGOs, social programs, nature conservation organizations and the like. It differs from the redistributors described above as this give back profit model gives back according to its own gains. This ideology stipulates a company should make a profit before giving anything back.

Often, companies operating along give-back lines donate to private charities that don’t have any direct ties to their own branch of expertise. Evergreen, for instance, is a company selling insurance services. Their main USP: 25 % of their profit goes to a wildlife organization. Internet browser Ecosia works the same way, using ad revenue to reforest the world’s driest areas, one tree at a time.

This way of giving back works well for companies who don’t want to take too big a risk: donating to charities with a well-established network means you don’t have to do all the work yourself and you can avoid shifting too much power to players in your own industry. Plus, no questions are asked on how they made that profit in the first place, nor how much possible damage or costs was added to the world.

Those who share the knowledge

Some companies have done the maths and concluded that giving (almost) all their expertise away is the best route to building a sustainable business. Opting for the open-source path, they share the knowledge and the love, knowing that it will multiply.

In tech, this approach has been part of the deal since the dawn of the internet and lives on in the philosophy of organizations like Red Hat, founded to develop software for companies and sharing it with others once it’s been built. This way, a much larger circle of companies profits from Red Hat’s technological advances at a fraction of the cost. Non-technological industries have followed the open-source example, too. Some, like New York-based lawyer firm Baker McKenzie, share insights on a broad range of legal aspects and even offer pro bono work to benefit the community.

These companies share their knowledge, but still create a steady stream of revenue by advising clients on how to apply that knowledge to their specific context. Because while you can synthesize bits of knowledge into blogs, eBooks and whitepapers designed to advise laymen on how to tackle their issues, chances are these laymen will still be glad to have a helping hand to put the advice into practice. Profiling yourself as an authority on a certain subject by sharing your knowledge will showcase you as a go-to source for anyone in need of advice on your particular terrain and it will grow the collective intelligence on the topic exponentially.

The data dividend sharers

A lot of the new tech players earn gazillions with the user data they harvest. But they could also let consumers share in the profit made on selling their data to third parties. Not too wild a concept, seen since the data actually belongs to these very consumers.

Datacoup mines users’ personal data, and allows these same users to sell crumbs of their online lives for 8 US Dollars per month. This way, the company says, they are “giving transparency and money back to people for their data, ” a practice that “stands to disrupt a surreptitious $300bn market.” They try to outsmart what Shoshanna Zuboff dramatically calls ‘surveillance capitalism’. The few getting rich on the data of the many. And there are others out there claiming their share of the cookie. Cake is a banking app that analyzes its customers’ financial data and helps optimize their daily income as well as their spending. To boot, they share 50 % of their data-analysis revenue with active Cake users.

These types of setups are usually technology-based, meaning they scale rather easily. Moreover, they are part of a wave of slightly rebellious brands who view technology as a means to give power back to the people – a trend that has the potential to become much, much bigger and severely reshapes some industries who have been at a standstill for too long.

Steal from the best

Some of the drivers behind these formats are more economic in nature (like the data dividend model), others push the environmental cursor (sharing economy, solution economy and circular economy). The three that are left (the distributive, give back profit and knowledge sharing models), strike the right balance between being economically, environmentally and socially responsible. In choosing the right fit for your plans, you’ll have to make choices that mostly depend on the type of product or service you offer.

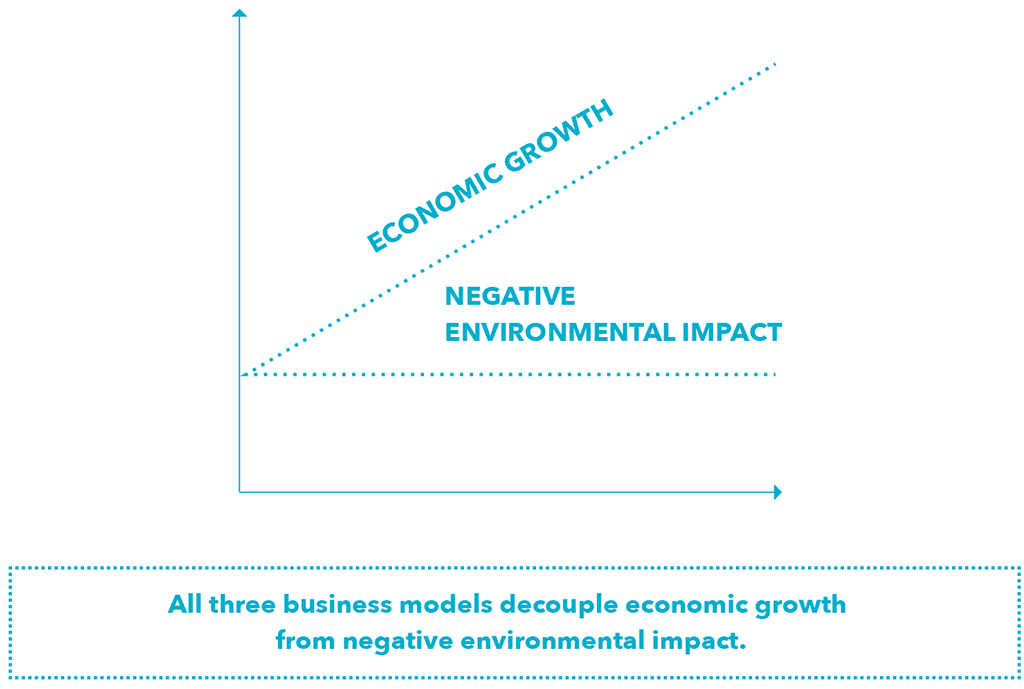

WHY ARE THEY SUSTAINABLE

Keep in mind that there is one element that sets the three environmentally inclined models apart from the others, though. What they have in common is that they have decoupled growth from a negative environmental impact. Their methods to scale their business will help them grow in size and turnover, but they won’t have to burden the planet doing so. They’ve replaced products with solutions. They’ve turned finite sources into materials that can be used and reused ad infinitum. And they’ve altered our need to own, making us realize the benefits found in sharing. If you’re looking for ways to make your metasystem company a success, we strongly recommend stealing ideas from the best.

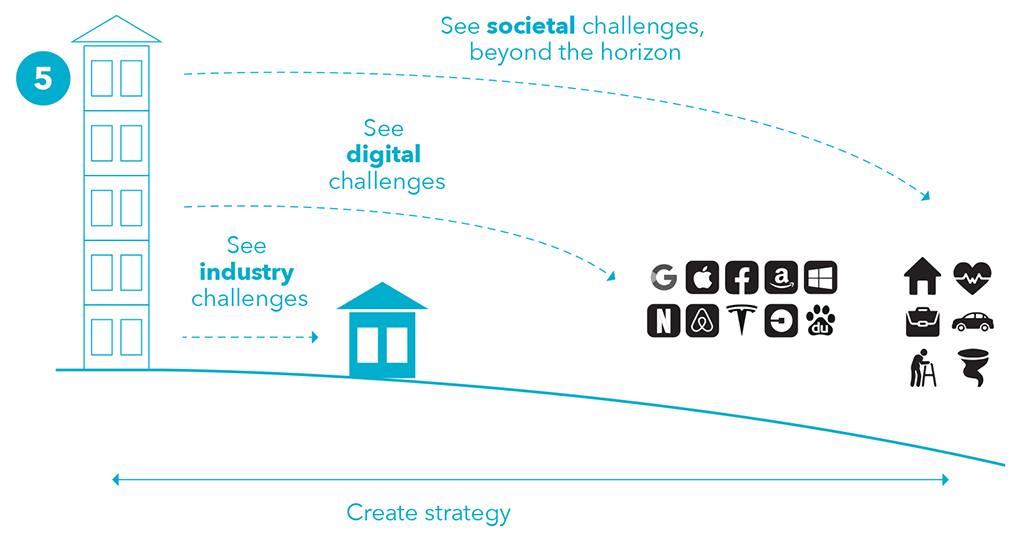

The 5th floor perspective

Seeing into the future is hard. But that doesn’t mean we can’t try and make out the shapes dancing at the horizon. Squinting is one option. Colleague Jo Caudron prefers to climb up high to enjoy more of the view. Jo – and that’s why we like him so – is interested in the broader societal disruptions that we are facing. To him, choosing a higher-up vantage point offers a more optimistic future perspective as well as a framework to deal with the changes at hand. In order to stay ahead in the game, he proposes to change our outlook on things.

The ground floor perspective

For decades, companies have built their strategy from the ground floor perspective: they mainly looked at their direct competition to keep the pulse of innovations or shifts in the market, or to predict their own future. Some maybe even looked at industries akin to their own. Things weren’t all that complex, really. In most situations, it was enough to extrapolate the last years of company activities to project a more or less reliable image of the future. Company directors – which is what CEOs were called, back in the day – needed only to add some revenue growth, extra market share, or cost reductions to draft their strategy. Whenever a competitor launched an innovation, it was enough to copy it to be on par again. While companies did look left and right to stay in touch with the times, they rarely looked up, nor did they look further. Mostly, they were on the ground level. However, this perspective shifted in the early 2010s.

A ground floor company mainly observes the challenges and changes happening in its own industry. It has limited view on what is happening outside that scope.

The 3rd floor perspective

With the recent digital transformation came entirely new challenges. No longer was it enough to understand the ins and outs of one’s industry to be future-proof. Now, leaders also needed to see and understand the disruptive potential of the new technology players: from the overhyped mosquito bites called startups to the lethal shark bites of the big tech companies. Those in charge needed to move a few levels up, in search of a bird’s eye view, a broader perspective.

This is now. Most companies realize that to be ready for the future, they have to look beyond their traditional market and expand their view to include players in the digital world. Most competitive companies today are on the third floor, scouting the horizon for movement. From this vantage point, they can see more and better prepare their digital transformation strategy.

But what if that isn’t enough?

A 3rd floor company observes from a higher perspective and is able to respond to challenges coming from the digital world.

The 5th floor perspective

It is our strong belief that companies who don’t understand the societal disruptions they’re right in the middle of will no longer be able to draw up a valid strategy. While today, the transformation is digital, tomorrow it will be societal. And it will set the winners apart from the losers.

To cope, companies will have to operate from the fifth floor. Climbing higher up, they will be able to observe the world, not just their industry or the digital wave flooding it. CEOs will have to connect the dots from industry, digital and societal changes to see the future. Unfortunately, there are not a lot of 5th floor companies yet.

A 5th floor company observes from a higher perspective and is able to respond to challenges coming from the digital world.

An example

Let us give you a retail example to clarify. A ground floor company would monitor (and copy) the competition’s every move: A lowers their prices, B follows. A modernizes their stores, B calls the contractor. A introduces self-scanning, so does B.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. A 3rd floor company would do the same. Except on top of all of the above, it would anticipate the digital challengers: it would step up its e-commerce game, introduce free home delivery, and so on. A 5th floor company would also try to understand what society could look like in a couple of years from now. How will people work? Where will they live? What is the environmental footprint of these activities? Will anyone still have their own car?

Only when you reflect upon all these topics and understand how they can impact the future, will you be able to create a future-proof strategy. Just imagine that people would indeed move about less in five years from now. That would dramatically impact the traffic to this retailer’s stores in the outskirts of town. Far-fetched, you say? Maybe. But it’s a fact that in under a decade, the number of driver’s licenses that were issued in Belgium dropped by almost 20 %. Another fact: in that same period, the number of people without a car increased to over 50 % in Ghent, one of Belgium’s most progressive cities. What floor are you on? What is your perspective on change? Are you still a ground floor company, gazing at the other dinosaurs? Or are you already on the third floor, actively trying to understand and anticipate the digital disruptors? And, most importantly, how will you make it up to the fifth floor?