CHAPTER 3 BUILDING BRIDGES

If our brain can change the shape of the Earth from flat to round, it can surely build some bridges between seemingly opposite directions or phenomena – especially if we as a species spot an opportunity to thrive on that switch. While structuring the chaos surrounding us, we have made some divisions which were useful once, but now may appear somewhat outdated.

In this chapter, we’ll walk you through some of these man-made divisions before erasing the arbitrary borders between them. This list is by no means complete. As we are trying to make a point, we have picked a few oppositions which are exemplary for our old paradigm crumbling. May this list inspire you to change your goggles, look around and refrain from dividing, categorizing and simplifying in your quest for certainty.

Nature vs. Technology

Have you ever felt that spending too much time on a screen means you’ve somehow forgotten to notice the birds singing and the greenness of the grass? Technology can make us feel estranged from nature. The more time we spend on screens, the more popular log cabins become for quick week-end escapes – especially the ones without a Wi-Fi signal, to offer some respite from our digital presence. You could argue that we’d benefit from going back to our roots and go live in a cave. However, most of us are not Bear Grylls and wouldn’t last in the wild for more than a day. Mankind needs technology, in the first place for survival.

But we can’t ignore the underlying feeling of troubles in our hi-tech paradise. Our relationship with technology was wild and exciting at the beginning, but now we find ourselves stuck in routine and highly dependent on all sorts of gadgetry with a very dubious relationship towards our identity and privacy. We’re not advocating divorce, though. We just think we might take some counselling together to try to work things out and find a better way to live together since we’re stuck anyhow. The feeling of unease towards technology does not emerge from its DNA, it’s the unwanted side-effects we have talked about earlier that make this relationship so dubious. But to throw out technological solutions altogether because they make us feel ‘unnatural’ is laughable.

Luckily, academics and thought leaders are stepping up the debate on the relationship between (human) nature and technology, finding out how we can build, use and interact with technology in a more sustainable way.

In the category of biological nature (all that is not human), scientists, engineers and designers have been researching the relationship between nature and technology for decades now, and boy have they developed some genius applications!

The biggest R&D department in the world

Biomimicry is a way of searching for innovation by mimicking patterns found in nature. The idea behind this is that nature has solved numerous challenges we too are faced with. In other words: we might learn a thing or two. Because in a way, all of nature’s creatures are engineers: ants, microbes, otters… Compared to us, nature has had billions of years of ‘agile development’ to find the best configurations for survival, making its solutions thoroughly time-tested.

Nature has resolved a whole lot of engineering problems. Think about a self-healing lizard’s tail, beetles and camels finding their way to water in extremely uninhabitable and dry surroundings, deep-water fish living in an environment containing almost no oxygen. Seeing how the fauna and flora that surrounds us is mostly designed and developed with careful genius, you’d almost think us humans have been rather shabbily crafted. Which is why divorcing technology would never work. The point is that nature provides us with a lot of ‘proven technology’.

In science, biomimetics is a discipline dedicated to consider all this natural research and apply it to tackle human challenges in a more circular and sustainable way. In recent years, it has gained popularity. Just to give you an example, Japanese bullet trains were inspired by the kingfisher; a bird with a long, narrow beak. Older generations of bullet trains would make a loud, booming sound whenever they entered a tunnel. Thanks to a redesigned nose that resembles a kingfisher’s, the trains now experience less friction and don’t wake the neighbors anymore.

Other examples range from wind turbines shaped like a humpback whale fin, with small ridges that allow them to cut through the air, or as over a shopping center in Zimbabwe which used a ventilation system inspired by the way termites construct their tunnels, to space crafts taking lessons in shock resistance from woodpecker’s beaks.

Stewart Brand, the editor of the first Whole Earth Catalog (a magazine from the 60s also known as Steve Jobs’ bible), was a big fan of biomimicry too. He realized long ago that the best tools are the ones nature has already invented. Brand – and Jobs after him – tapped into the hidden power of nature to come up with strategies and solutions. Today, their legacy lives on. In fact, the symbiosis between nature, (digital) technology and the application of these learnings in non-technical domains has never been this strong.

Neural networks

A great example of how technology and nature can come together to reinforce one another can be found in the acceleration of artificial intelligence. Instead of programming algorithms in a linear, causal, if-this-then-that structure, artificial intelligence is wired as if it were a brain, a distributed network of nodes intertwining, collaborating and processing at a speed we can’t begin to follow. Furthermore, these neural networks are self-learning, meaning programmers allow a certain level of freedom and uncertainty into the equation. Man is letting go of some of his power.

This is an extremely important step towards what the more apocalyptic types call ‘singularity’, the tipping point in time when AI will surpass human intelligence. The day of our last invention, so to say. While singularity is too big a subject to cover in detail here, the fact that its due date is fast approaching makes a very good point on how biomimicry is relevant for organizations. By moving from a linear to a more dynamic way of programming – by mimicking our brain – developers have taken an immense leap in shaping AI. A true example of innovation on the verge between nature and technology.

Nature’s comeback

Biomimicry’s uprising can also be linked to nature’s innate talent for sustainability. Nature doesn’t strive for maximal profit, it aims for an optimal situation in its ecosystem as a whole and endeavors to be as resilient as possible, always ready to absorb unexpected blows. Nature doesn’t do garbage. It is a system in which nothing is ever lost. A closed loop of herbivores eating plants, being eaten by predators, dying, becoming humus and feeding the plants again. Seeing this technical ingenuity forces us to let go of the supposed opposition between technology and nature. Nature is hyper-technological, so maybe now is the time for man-made technology to become a bit more natural.

While biomimicry is gaining traction, its popularity isn’t solely caused by the large number of unresolvable questions in high tech. Its rise happens in parallel to the complexity of challenges we face, such as climate change – challenges that demand sustainable solutions as well as swift action. And that’s exactly where biomimicry makes the difference. Not only does it inspire us, it is what economic theory labels an ‘economic game-changer’, precisely because it unites economic value and sustainability, moving beyond oppositions like profit versus impact, nature versus technology, money versus futurism. It’s a hybrid approach to nature, mankind and technology, fostering sustainable innovation.

A CASE FOR NATURE VS. TECH

MURMURATIONS

Murmurations are a phenomenon where hundreds, sometimes thousands, of starlings fly through the sky in swooping, intricately coordinated patterns before settling into their roost for the night. Just as interesting and much more fun to look at than an Artificial Intelligence (unless it’s Scarlett Johansson). Because while the birds’ song and dance surely please the eye, this phenomenon is also packed with lessons for those interested in optimizing the way teams work.

How the starlings do it

1. Safety

Together, starlings are better protected against predators. It’s harder to attack a whole flock than it is to attack one starling.

2. Social cohesion

The shape of the flock allows the birds to quickly share information about feeding sites or imminent threats. The flock is designed to serve as one big communication medium.

3. Warmth

The bodily heat of those thousands of starlings flying in formation raises the air temperature around them, providing the starlings with much-needed warmth during the long and cold winter.

How on earth do they organize themselves? Actually, it’s not as complicated as it looks. Research shows that each bird follows the movements of the seven birds flying around it. Combine this with the birds’ lightning-fast reactions, superb spatial awareness and swift communication, and you understand why the flock reacts and moves as quickly as it does.

Progressive as they are, starlings opt for collective instead of individual leadership. This means the movement of the flock is governed collectively by all of the birds. In the flock, the position of the birds defines their role: birds at the edge of the formation detect opportunities and danger, while others pass around the information instantaneously and collectively.

These roles aren’t set in stone, though. A starling that’s stationed at an outpost once, doesn’t remain there forever. As the flock moves, birds take turns at the front, sides and back, switching roles as they go. In murmurations, there is no status quo: birds swap roles and positions like a cheerleader squad going all Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.

Trust vs. Control

Two phenomena that find themselves at the far edges of the spectrum, are trust and control. At first sight it seems that you’ll have to choose b etween the two, as a lack of trust leads to control and the other way around. We’d dare to disagree. If you’ll recall the wicked problems of Chapter 1, and remember that the way we respond to them is an unfortunate paradox, you can sense the contradiction. When the world gets messier, we need to let go. We need to trust in order to regain control. Uncertainty demands a certain level of trust, of freedom, in order to be manageable. And seeing as we find ourselves smack dab in the middle of two paradigms, you better be sure it’s uncertainty that will reign over the next decade. Don’t let this discourage you, as it opens up room for the unexpected. For serendipity.

It sounds like a romcom. And it is, but that’s entirely beside the point. Serendipity is also the phenomenon of accidentally discovering something good and creating value through the unexpected. Serendipity cannot be staged or manufactured, but it can be fostered, as it is the outcome of a certain attitude, a trustful and playful openness that allows you to acknowledge all the things you don’t yet know. It is you giving permission to the universe to surprise you.

It’s what happened with Post-It. In 1968, an engineer at 3M wanted to develop a new superglue for the flight industry. It would be the strongest glue mankind had ever seen. Regrettably, there were issues in the development process. The glue wouldn’t stick, and objects came apart faster than a boy band in the 90s. However, the glue turned out to be reusable and didn’t leave any marks. An innovation in itself, this kind of glue didn’t have an application – yet.

The power of serendipity is everywhere, but it is usually dormant. Alexander Fleming invented penicillin by accident. In fact, he wasn’t even around for his own invention. Because he hadn’t done a very good job of cleaning the petri dishes he’d left in the sink before leaving on holiday, Fleming returned to find a fungus had emerged around the bacteria he was experimenting with, keeping those bacteria at bay. While Fleming’s research hadn’t been geared towards developing an antibiotic, he was the accidental inventor of a true lifesaver.

This shows that the moment you stop focusing on an already formulated hypothesis, a preformulated answer to your questions, the possibility of serendipity arises. This applies to companies as well. In business, you constantly try to answer questions asked by customers, your staff, even society. Thinking you have all the answers upfront doesn’t leave any room for serendipity, though, which nips your chances of stumbling upon radically new innovations in the bud.

Allowing serendipity into the business realm leads to unplanned and unintended innovative value. It is a way of taking advantage of unanticipated, unexpected and unsought information. This is the stuff moonshots are made of – those futuristic ideas that might feel like money down the drain today, but might just as well propel your company into the future.

When faced with a messy world, an outdated paradigm and uncertainty, the choice between trust or control is a false one. It is true trust that you will regain a certain level of control. So again, not either/or, but and/and.

Fast vs. Slow

We have a very dubious relationship with time. It serves as a currency in the economic realm but is also our biggest source of freedom outside of it. It dictates our agenda and priorities on a daily basis. Sometimes, you could swear time goes faster when you need it most and lingers when you want it to move faster. However, calling it an invisible enemy we need to control, or advocating we should keep on running to and stay ahead of the clock, would be too simplistic.

There is clock time, and there is experienced time, and the two shouldn’t be confused. The more you interact with people, the more human the activities on your schedule, the more you are dealing with experienced time. This time feels stretchy and isn’t usually efficiently used. When you are working with machines, optimizing automated flows, or fixing your garden’s irrigation system schedule, you’re dealing with clock time. Clock time is fixed, clear and objective, always linked to efficiency.

The fact that there are different types of time already debunks the opposition between fast and slow. What is fast to one person, in a certain context, is impossibly slow to another. Speed is a subjective thing. We suggest you refrain from even having a preferred level of speed. ‘I like to take things slow’ or ‘Speed is of the essence! ‘ are actually nonsensical statements. We might translate them as, ‘I like to do things very thoroughly’ and ‘I don’t care about quality, I care about deadlines’. But that says more about who’s talking than about the concept of time. Time is a balance between quality and quantity. And just like the other seemingly opposites in this chapter, we’d advise you not to choose one or the other, but try and find a balance.

EXPLAINER

FESTINA LENTE: THE ETERNAL SEARCH FOR BALANCE BETWEEN FAST AND SLOW

One of the favorite sayings of Roman emperor Augustus was ‘Festina Lente’; ‘Make haste, slowly’. It emphasizes the dubious relationship we have with time. Both speed and patience are seen as virtuous, but on the surface, they seem to exclude each other. Augustus tried to solve this conundrum by making a division between decisions that were made with ‘haste’ and those made with ‘speed’. Haste, to him, signified being mindless. Speed, on the other hand, represents the maximum speed you can achieve when thinking things through before you act. We all want speed and progress, but not if the decisions have been hastily made. Nobody likes to receive an email yelling ‘ASAP’ right in the subject line. But before we all started misusing this abbreviation, it was pretty similar to Augustus’ way of seeing things. ‘As soon as possible’, with possible being a synonym for qualitative, desirable, mindful, and correct.

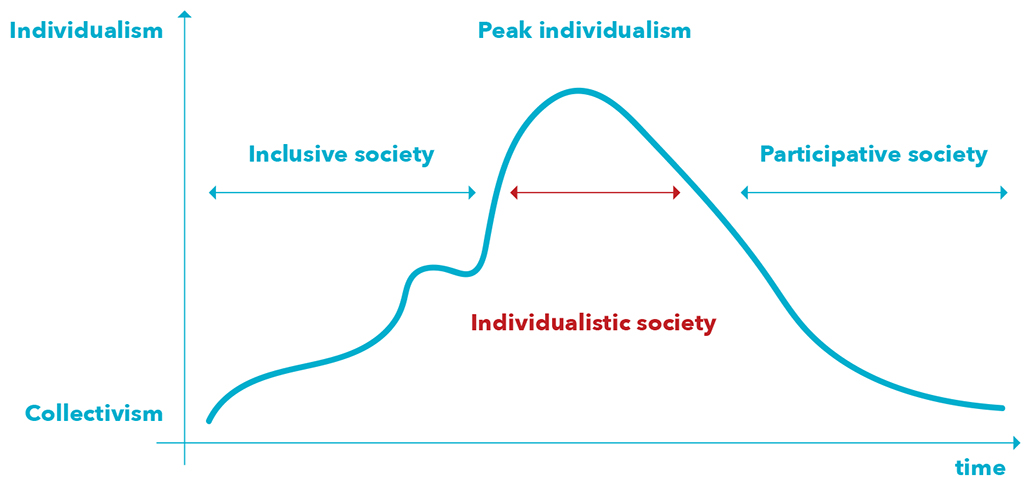

I vs. Them (or the battle that got cancelled)

There seems to be a general belief that we live in very individualistic times. Selfies, customizable sneakers, self-care, self-help and self-development manuals are everywhere, as are coaches and therapists for every taste. The term ‘peak individualism’ has been coined, framing this perceived state of self-obsession we are in.

Are things really this binary, though? Do we live in a world where people can’t collaborate, can’t look past their own interest, have no sense for the common good? We don’t think so. In fact, people get along very well most of the time. In business as in our private relationships, collaboration and respect are the rule, not the exception.

We believe there is a more nuanced, fruitful domain to tap that lies somewhere in between these opposites and occupies the middle ground between pure egotism and an outdated form of communism. The I vs. them battle doesn’t need to be fought, we need to find each other in the middle.

Interdependence day

Back when the world was simpler and the animals could still talk, capitalism and individualism thrived on the ideas of freedom and meritocracy. But then businesses weren’t being disrupted at a killer pace, politics weren’t so polarized, and the future was still somewhat predictable. No need to despair, though. With individualism reaching its peak, we might begin to see and appreciate our interdependencies more clearly. We seek out connections again, carving out room for a collective fiber as an answer to uncertainty. We set about finding collective solutions to our collective problems.

Modern media may have estranged us from others in some ways, but it has also shown us how intrinsically connected and intertwined we all are. A blogger may be promoting herself on social media and building her personal brand, but she depends on many others to keep going. The people designing and making her computer, the guy proofreading her writings, the ones who like her pictures and buy her how-to-blog book.

And so the possibility of an alternative opens up. The sound of a more participatory society resonates a little louder. When faced with a crisis, solidarity thrives. The worldwide pandemic wreaking havoc as we write this book may have pushed some people to start hoarding, but the majority quickly understood that in a pandemic it’s just like taxes: the moment one person starts cheating, the whole system is about to be stretched to its limits. Solidarity is the acknowledgement that we, humans, share a common ground, so that taking care of others is the same thing as taking care of yourself. This isn’t a realization you can impose. Luckily, solidarity doesn’t need imposing. It’s in our nature to care for others.

We are all interdependent, more so now than ever. The startup CEO who sells his unicorn and pockets his millions could have never done so without his team, his investors, his cleaning lady and the barista on the corner. The individual is a fairytale, and a pretty lonesome one at that. We might as well let it go.

Because social cohesion isn’t simply imposed top-down, we will have to look for other ways of managing the whole, though. These could take the shape of organizational structures that are carried by all actors and are based on trust, reciprocity and a healthy amount of skin in the game. We will need to design new systems. And since imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, we might take our cue from the design principles of the commons and steal what is of use.

A CASE FOR I VS. THEM

THE STORY OF THE COMMONS

Commons are resources that belong to, are owned by and managed by a community. Think of those communities in the broad sense. All the fishermen of South-Wales are a community, as are the 5th graders in a small town in Minnesota or people who have nothing in common except their location; like everyone living next to lake Tahoe or those who use the empty space next to the highway to park their cars. The same broadness of definition applies to resources. These could be the fishermen’s fish, the boats on the lake, the toilet paper available for the 5th graders, but also space to walk, to park your car or to store stuff you don’t need anymore.

In economic and political history, literature often refers to the Tragedy of the Commons, a title with quite some flair for drama. The story goes like this. When you give a community the freedom to organize a shared resource any way they see fit, things get out of hand. Worse: it ends in tragedy. A few take it all, most are left empty-handed, the community ends up bruised by all the conflict and long-term perspectives are cut short.

Risky business

Labelling the story of the commons as a tragedy is one way to interpret history. But history is messy, and so are people – even scientists, economists and political experts. Humans aren’t strictly rational. Anybody claiming so is only fooling himself. (Which, incidentally, proves that point.) In fact, we are all cognitively limited, which is a polite way to say we’re all over the place. One of humanity’s flaws is that we are much more sensitive to negative information than to positive information. So, if ten stories were told about the commons, and three of them didn’t have an ideal outcome, the three of them take the upper hand and the whole becomes a tragedy. You can call it a negative bias, or blame the drama queen hidden inside all of us.

Under the surface, there are dynamics playing against us, things happening outside of our control. We are ruled by unruly emotions, driven by fear, instinct and needs. These hidden forces are humans’ greatest flaw. This capricious ego of ours poses two risks to managing a commons successfully.

Firstly, our self-knowledge is flawed. Socrates was one of the first to say that if you want to do good, you have to know what is good. The man has a point. If you want people to do the right thing, they at least have to have all the information needed to do so. That means knowing as much as possible about the resource itself, what it’s made of, what it needs, etcetera. But it also means we should know our own heart. We should understand what drives us, read our motives and know how to overrule our basic instincts. It means recognizing that our human impulses might not benefit the group. If our brains don’t have all the information they need, the dataset is incomplete, and we are prone to mistakes.

Secondly, people are no saints. Our benevolence is limited. Our own survival is always at the top of our list. And maybe that’s a good thing, because nobody else will put your survival first. However, we do recognize that, sometimes, what is good for others is also good for us. Or, as Kant put it: never do something to somebody you don’t want done to yourself. A certain level of benevolence is embedded in most people. Most of us are able to imagine what is good for others. We strive for it and even fight for it. But we are often unwilling to contribute to the good of others if there’s nothing in it for us. Not a calamity per se, but an inclination that might prove problematic if ignored.

These imperfections in the human character can lead to the destruction of the commons when we put our own short-term interests before the common good. Given enough leeway, they will open the door for free-riding, overconsumption and underinvestment.

These kinds of dynamics dry out the resources before anyone can yell ‘bingo! ‘. What we have on our hands then is what is called a tragedy of the commons. However, these tragedies are not the rule. They are the exception.

It’s not that bad

We’ve said it before and we’ll repeat it until we’ve rewired you: people tend to focus on the exception, not the rule. In common-pool systems, free-riders are the exception, not the rule. Yet the stories about them stick. We get it, they’re juicier. But we collectively underestimate the negative impact this focus on everything out of the ordinary has on our lives.

The commons prove that if we learn to acknowledge and accept our own imperfections, we can work with them in ways that don’t end in tragedy. The free-rider problem is usually presented as best resolved by external regulation (i.e. adding a management layer), while it is actually better addressed by relying on the ingenuity of those most affected by the misuse. The commons teach us that rules that have been made by those with skin in the game have fewer exceptions. In other words, people don’t need more managers. Let them co-design the rules of the game and they will be much more likely to play within their boundaries.

Another way the commons have taught us to bypass our flawed minds and hearts is by offering incentives, a system we know for a fact people respond to. Again, these can be imposed by an external entity, like a legal system. But incentives are much stronger when they are ingrained in a community’s culture, when they appeal to our sense of right and wrong. Like keeping a promise or doing the right thing, taking just what you need becomes second nature.

Commons are not as bad as they look. In fact, there is a rich collection of examples of well-functioning commons that don’t thrive by the grace of hierarchy.

The teachings of the commons

If we acknowledge the level of interdependence between actors in society and we realize that most of the challenges we’re facing are collective problems, not individual ones, the commons might make for a relevant source of inspiration. As an organizational structure they move beyond the false opposition or battle between Us and The Rest Of The World.

The commons show us that systems are made out of people, and people are messy. But given enough information and a level playing field, we are all capable of trust, long-term thinking and even a little benevolence. An idea worth believing in.

Profit vs. Purpose

There are the dreadlocked activists on sandals saving the planet on one side of the table (mostly women), and on the other side, you have the CEOs in freshly pressed suits (all men) with gold watches, twisting ice cubes around in a glass of bourbon. That’s how it works, right? The hippies do the purpose thing, the CEOs handle the profit? Right? Nope. Maybe in Mad Men, but not in real life. Especially not in this decade or the next. There is no need to suffer like a messiah if you want to contribute to a better world. Neither is it evil to want to make a profit.

Mr. Burns has left the building

There is no opposition here. No either/or. Only and/and. Making profit and having a positive societal impact are heavily intertwined. The times of believing you can go for profit while using more of this planet’s resources than you need, or regarding your staff as easily replaced cogs in a machine are over. We have, at last, discovered that the true cost of irresponsible profit-making doesn’t fade away, it merely skips a generation.

If profit is the only goal a company has and this goal justifies any means, then this company has all the makings of becoming a monster. One that only thinks about money, winning, taking, harvesting and short-term bingo points. These monsters exist but are increasingly being called out for what they are. In this century, consumers expect companies to think about the long term, act responsibly, be human, reap and invest. Mister Burns is becoming an image of the past, taking with him the side of the table that still can’t see beyond the Dollar bills.

A suit doesn’t hurt

On the other side of the table are the smelly hippies. We are sending them off, too. While many activists feel extremely responsible for the well-being of the planet, they are hindered by a lack of holistic vision that undermines their good intentions. As long as they ignore the way the world works, they will not achieve the impact they hope for.

When trying to change a system from the outside, it can be very hard to achieve anything more than annoying the ones who are on the inside. If you want real impact, you have to understand the ins and outs of the system you want to change. Any organization meaning to save the planet or the animals or whatever noble cause, will have to build a financial basis. Because if you preach sustainability, you’d better be sustainable yourself. If you want real change, it will always be systemic, and this includes the economy, or the ways money works. So, that’s the other half of the table cleared out.

Of course, we don’t mean to hurt the feelings of activists or CEOs. Forgive our clichés, we only aggrandized the prevailing image of both stereotypes to make the following point clear and firm. Sustainability goes beyond ecology, purpose goes beyond a private feeling of responsibility and your responsibility should be proportionate to your power. Big players, big impact, big responsibility. We want to make a plea to blow up the border between the for and not-for-profit sector. And we’ll do so more elaborately – and rather more eloquently – further on in this book. Because we strongly believe all citizens, companies and consumers should move beyond our greediness for profit if we want to make progress.

EXPLAINER

WHAT ARE THE 45° THAT MATTER?

In our business, we use this term to define how you can place dots on the horizon, keep your focus on them, but remain flexible while moving in the right direction. Instead of drawing a straight line that takes you straight to your purpose, you draw a 45° angle towards those dots on the horizon, allowing a little wiggle room while making your way there. This is your longterm view. From now on, every move you make, every step you take, is in light of these 45°. However, this angle is no dictate. Consider it to be the beam of your flashlight: it indicates, guides, and also leaves certain areas in the dark, keeping you on track.

Emotion vs. Reason

We tend to forget that humanity is made of people. We may long for simplicity and objectivity, but unlike numbers, people are messy creatures that don’t fit into a spreadsheet. People are everything at once, propelled by instincts which may very well move in opposite directions. We have expectations. We want to develop ourselves. We have preferences. We are good at some things and bad at others. When making a tough decision, like between two lovers or jobs or places to live, we can make a list with pros and cons, kidding ourselves that our rationale will make the call, but knowing full well that in the end, it’s our gut feeling that decides.

Accepting this as a fact of life can be a true liberation, and will make your attitude towards other humans more understanding and benevolent. But if you work in a company that ignores this fact, or the fact that its main ingredient is humans, you are bound to feel out of place and underperform.

Companies that don’t take into account the human nature of their people and their resources are slowly but surely becoming an exception, yet they still exist. Their behavior will be increasingly hard to account for. Their staff will revolt against their lack of empathy, not accepting to being treated like machines or disposable resources. Their customers will find alternative products to buy. In the long run, this stance will cost a profit-obsessed company its reputation. Next, it’s their profit that will plummet, hitting the company right where it hurts the most.

Luckily, there is a flip side to the medal. This ‘messiness’ that is so typical of human beings is also the precondition for creativity, for innovation, for going the extra mile. And these are all traits a company needs to thrive. And these are not the jobs being taken over by technology. The human jobs of the future will be the jobs that require us to play out our human side. Companies will need our messiness to do everything robots can’t. Companies who can harness this human side will be the ones to outrun the competition. Everybody else can just go and buy the exact same software license.

However, companies need more than creativity and emotions. They need our brain power as well. Despite the old beliefs made up by some old philosophers, emotion and reason are not arch enemies. Much to the contrary. When combined, both elevate one another and get along mighty well. In the theater that is our inner world, reason and emotion are the dynamic duo on stage, forever wrapped up in a dialectic movement. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis and then the same thing all over again. We feel, we think, we reason, we check with our gut feeling, review and we make a decision. This feedback loop moves from our heads to our hearts, back and forth, back and forth.

Ignoring either the emotional or rational side is a sure-fire way to get in trouble. You’ll probably find a name for that ailment in any psychology textbook. If this is true for humans, it applies to companies as well. Why business has focused on the mind rather than the heart, is hard to say, other than to point out this was how things were historically constructed. The more important lesson to remember is that the times they are a-changin’. Companies = humans. Humans = emotion + reason.

Now vs. Later

People have an ambiguous relationship with time horizons. In the past, out of necessity or out of conviction, many of us were used to delaying our pleasures, our rewards. We were told first to save money before spending it on a new car or an unforgettable holiday. Collectively, we were prepared to live a hard-working, law-abiding life with a lot of hardship. We were content to know we would receive our reward in the afterlife. We still see this way of living in many developing countries, especially those with a catholic heritage. In our western society, we’ve moved on from postponed happiness; instant gratification has become the standard. We want it all, we want it now and we don’t want to use too much effort in order to get it. This shift is one from delayed to instant gratification.

In business, the debate of long term versus short term has always been a heated one. Sometimes this causes polarization between the “visionaries” wanting to invest for the future and the more controlling types who only want to spend money after it is earned. There’s the “can’t make an omelet without breaking eggs” school on the one side and the “better safe than sorry” on the other.

In many companies, broaching the long term versus short term subject is akin to opening Pandora’s box. Preferably, you’re able to walk and chew gum at the same time. This only proves how difficult this economic conundrum really is. Balancing the short and the long term is relevant, but so is knowing when is the right time to invest and the right time to be frugal.

With climate change an additional layer of complexity has been added to the debate. Soon, our Mother Earth will be unable to digest our expanding consumption behavior, our unsustainable production methods or the way we use up natural resources at break-neck speed. The impact of our behavior is slowly becoming visible in the shape of melting ice caps and plastic polluting our oceans. And this is only the tip of the iceberg, given our conviction that all people have a right to decent living and a certain level of comfort.

Add to that the fact that our population will continue to grow for another 50 years at least, plateauing somewhere between 11 and 12 billion people, and you know that we can’t possibly go on living the same way with almost twice as many people. Between now and later, we need to solve one of the biggest problems in our economic model. Every generation should leave a positive legacy to its prodigy. Only if we leave the place better than we’ve inherited it, will we be able to reflect proudly when we talk with our grandchildren.

The tension between now and later or the short vs. the long term proves that choosing is losing. As we saw in all the previous oppositions we’ve tried to debunk, winning equals realizing that we should strike the right balance between both, not pick either one or the other. Because there is a lot to lose if we radically opt for either one. We need to focus both on the short term, dealing with the world as it presents itself to us today, but at the same time it’s paramount to keep an eye on the horizon. Today, we are allowed to strive for comfort and gratification, but we have to ask ourselves what the longterm cost is. And so questions arise. How do our short-term actions impact the long term? How does our behavior impact the natural environment? Answering these questions is, and will remain, a constant quest for balance. You will never obtain a perfect balance between these two-time horizons. Rather, you will have to become adept at the balancing game between the now and then, you and them.

INTERVIEW

BUSINESS MUST COLLABORATE DIFFERENTLY, TO GROW BETTER

AN INTERVIEW WITH OSVALD BJELLAND, CEO AT XYNTEO

Xynteo helps business leaders build a new kind of growth, based on defining opportunities to create significant social value and repositioning their companies at the heart of cross-sector coalitions aimed at serving those needs.

We meet Osvald in The Hague, where we talk about the shortcomings of the world’s current economic model. According to him, businesses and governments have to address three main issues. “Sustainability makes us rethink the man versus nature conflict. Next, there’s the question of inequality, with the few on one side and the many on the other. And finally, the model balancing between shortand long-term benefits.” Osvald deems the current challenges so big and complex that they cannot be solved without what he describes as an unprecedented level of partnerships and collaboration. However, he thinks this cooperation should involve more than just the business realm. “The solution is more active and joined-up engagement between governments, multinationals, SMEs, startups and NGOs alike.” To him, we’ll need systemic change to answer these three questions.

“We need to solve three systemic problems

our economic model is faced with: man

versus nature, the few versus many, the

short versus the long term.”

Certain sectors, Osvald believes, are hotspots for these systemic challenges. “Going forward, more of our problems are systemic,” he says, “particularly in the food, energy and transport systems. In order for the companies in these sectors to tackle these systemic challenges, they must be transformed, up and down their value chains, and across the private and public sectors.”

Osvald doesn’t just see problems, though – much to the contrary. “I am convinced that companies need to work together to be sustainable. While most still see this as a necessity, they’ll soon realize that being sustainable will also help them remain relevant and attract the right talent.”

Likewise, collaboration is more than a means to an end. “Most companies are still unable to spot “out of the box” options. Plus, they lack the cultural capabilities to adapt to cultural differences taking into account the bigger why.

Collaborating with other organizations that inherently have different, but complementary perspectives, will help companies to uncover the rich opportunities that lie in their own blind spots.” It creates what Osvald calls optionality.

However, cultivating successful collaborations that can transform systems, at scale and with significant impact, isn’t easy. “It requires generating high levels of trust that reach across organizational boundaries. Many companies struggle at this,” Osvald says, highlighting Amazon, Microsoft and Orsted as examples of companies that have mastered the art.

Asked for advice on how to build trust, Osvald mentions three priorities. “One: always communicate with integrity. Two: work together with good intentions, try hard and forgive mistakes. And last but definitely not least: do something together. You can’t just build trust by thinking and talking, you’ll have to act. Having a common goal, a purpose helps.”

OSVALD’S TIPS:

•Address the three key challenges when articulating your purpose: nature vs. man, short term vs. long term, few vs. many.

•If you want to build trust, be trustworthy yourself.

•Having time is a choice. Take time to connect with the leaders of your network. Make this a priority in your time allocation.