Back when my dad was alive, he and his old-timer friends liked to reminisce about making “camp meat.” This was code language for the practice of shooting a deer that was additional to whatever amount of deer you were legally allowed to harvest, and using the phrase in casual conversation implied that a cavalier and woodsy strain of lawlessness ran through your blood. As long as the animal was entirely consumed while you and your friends were in camp, and the bones were pitched into a river, there’d be no evidence of the crime once you left the woods and returned home with your legally killed quarry.

Killing an illegal deer for camp meat is more or less a bygone practice nowadays, though plenty of cavalier and woodsy meals still get cooked and eaten by hunters out in the woods. Motivations for these meals can be as practical as being out of food, or as whimsical as wondering what some critter would taste like if you cooked it over a fire. Usually, though, it’s a combination of the two: You’re out of food, or nearly so, which gets you to wondering …

I practiced for these scenarios long before they happened to me in real life. Starting when I was eight, my brothers and I would sometimes paddle our canoe away from our home on Middle Lake and through a channel that led into Twin Lake. We’d camp on an uninhabited island that was so small and so close to shore that a woman once yelled across the water that we needed to watch our language. But even limited removal from civilization seemed like an excuse to eat freshly caught bluegill fillets that were burned to a blackened crisp in an aluminum Boy Scout mess kit set over a ripping fire. Other fires back then cooked other meats, all of them equally unpalatable. A skinned-out English sparrow poked on the end of a stick like a marshmallow and dehydrated over a bed of coals comes to mind. So does a chipmunk that I shot with a .22 while out squirrel hunting with my dad when I was eleven. The animal was about as heavy as a pair of sunglasses and as fatty as a stick of celery. I cooked it on a spit over a fire next to our truck, and the meat came out so tough that my teeth felt kind of loose after I finished trying to pull it away from the bone.

Regardless of taste, those meals made me fantasize about getting into situations where I’d have to prepare camp meat in real life. Such situations finally began to materialize once I moved out West and started hunting remote country, where you need to carry your provisions on your back. Matt and I would pack into the mountains on four- or five-day hunts, sometimes longer. We’d skimp on our supply of food in order to cut down on pack weight. Then, after a few long days of eating little besides freeze-dried food and tortillas wrapped around blocks of cheddar cheese, we’d start to regret our judiciousness. By then the sight of a spruce grouse was enough to make our mouths water. We’d shoot the birds with arrows and then cook the meat over a fire. It always turned out bland when boiled, if not a touch piney. Clearly, roasting was the way to go. But that method had its own problems. When subjected to heat, the legs and wings of the birds splayed out in a spread-eagle fashion and always got completely dried out and overcooked by the time the breast meat was safe to eat.

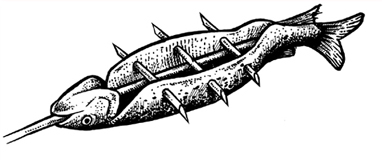

At some point, we started packing for certain hunting and fishing trips with the assumption that we’d secure food along the way. With this assumption came a desire on my part to learn how to handle what I considered to be the trifecta of common but difficult-to-cook camp meats: fish, game birds, and small mammals. (I don’t mention big game here because it’s almost too easy: just skewer kabob-sized pieces and cook them like hot dogs over a fire; it can’t be messed up.) Each type of creature presented its own set of problems, but I conquered those problems through gung-ho resourcefulness and a lot of tinkering. I hit on a memorable way of cooking fish while on a caribou hunt in the Arctic. When my friends and I tired of grayling and char fillets fried in a pan of sooty bacon grease, I tried breading them in Pringles potato chips that I pulverized between two rocks. They were sublime, though I admit that that recipe was like a culinary form of cheating. The first time I ever made a legitimately restaurant-worthy meal of camp meat was on a float trip in Alaska. We were catching coho salmon that were so fat you couldn’t grill them over a fire because they’d drip and burn, as if they were coated in lighter fluid. So we made fish baskets from willow limbs and roasted the fillets propped off to the side of the flames, the way they cook whole lambs in Argentina. In the Rockies, I learned of the perfect way to cook freshly caught trout over a fire without the use of anything but a knife. First gut the trout and pull out the gills, but leave the heads on. Then run the sharpened end of a skewer into the fish’s mouth and poke it into the flesh at the back end of the abdominal cavity. To keep the fish from falling off the skewer, whittle some sticks of green wood about as thick as the thin end of a chopstick and as long as your finger. Poke three or four of these perpendicular through the fish’s body, so that the skewer is wedged between them and the fish’s spine. It ought to look like this:

I got my first valuable insight into cooking small mammals when I was hanging around in Vietnam with my wife and my brother Danny. One day, we cruised up into the mountains outside of Nha Trang on rented mopeds. We were headed to a waterfall where you can jump off some cliffs into a plunge pool, but on the way we passed a small family farm that had a pile of coconuts and a bundle of sugarcane sitting next to a sugarcane crusher out by the dirt road. This was an advertisement for a refreshing drink that they make there with those two ingredients. While we sipped our drinks, I noticed a freshly dead critter lying on a log next to an outdoor fire. It was about the size and shape of a small opossum, with an opossum’s face and the tail of a squirrel. I mimed my interest in that sort of thing to the farmer, a man in his forties who was wearing nothing besides a pair of cutoff shorts. This pleased him greatly. He did an expert job of miming his reply: He’d just shot the thing out of a tree with an air gun, and it had had it coming because the animal kept getting into his corncrib.

The farmer tossed the entire thing, complete with the head, guts, and tail, into the embers of his fire. He stirred the marsupial around and around with a stick. Soon the hair was completely scorched away, yet the skin was still intact except for a few charred places around the knees, toes, and lips. The farmer took his machete and scraped away the ash and then gutted the animal. From the small pile of guts he removed the kidneys, heart, and liver, and put them back into the chest cavity, along with a few leaves and a pepper that he plucked from his garden. He sprinkled the whole thing with a bit of salt and an assortment of dried spices that he pinched from cups made from coconut shells. Then he wrapped the gutted and hairless critter with a few layers of palm leaves that he whacked out of a tree with the machete. He placed the package directly on a bed of coals.

We shared a few rounds of rice wine while we watched the thing cook. After about an hour, just as the leaves were beginning to smolder and burn through, he removed the package from the fire and peeled away the leaves. Using his machete and a block of wood, he split the animal down the spine and then chopped those halves into many small pieces. I lifted up a chunk that was adjoined to a heat-shriveled foot. The meat pulled away almost effortlessly. I was blown away. Using nothing but the things in his yard, this hunter had created a meal that I couldn’t have replicated with all the help of all the grocery stores in America. The meat had the dense flavor of perfectly seasoned squirrel, but with skin as fatty and satisfying as crisp chicken skin.

The hunter and his kill. Nha Trang, Vietnam.

Months later, I was still describing that meal as the highlight of my trip. It wasn’t long before I tried out the method on a squirrel: I singed off the hair and seasoned the meat, then cooked it over the coals inside aluminum foil. (There’s a paucity of palm leaves in many parts of America.) It worked perfectly, in that it was tender meat that tasted good. Next I tried it with a rabbit. Also good. Soon I struck on the idea of forgoing the foil and just letting the skin serve the same purpose. But instead of placing the meat directly on the coals, where it could burn, I suspended the squirrel over the embers on a rack of willow limbs. I knew that it was working when I poked the squirrel’s skin and the cooking juices squirted out like a squeezed lime. I realized that I was essentially braising the meat with its own liquids inside the container of its own skin; not much different than roasting a whole hog, just a hell of a lot wilder. And therefore, better.

Lastly, I figured out how to cook wild game birds as camp meat. My solution for these came down to patience and, to a lesser extent, trussing. Basically, you truss a bird by wrapping its legs and wings close to its body, so that it forms a tight little package that can be cooked in a uniform way. This is generally done with kitchen string, though in the field I’ve used strands of barbed wire, pieces of cable wire cut away from frayed and discarded logging chokers, and, in the case of woodcocks and snipe, by using the bird’s own beak as a skewer to pin the thick part of their legs to their breastbones.

Once the bird is trussed, you need to suspend it away from the fire’s flames but still within range of the fire’s heat. You want it close enough so that you can hold your hand next to it for about four or five seconds before you have to pull away. Spits set across two forked sticks that are shoved into the ground are great. So are pieces of wire hung from an overhead limb, especially if the wire is flexible enough that you can bend it in order to change the bird’s height and spin it around.

However it’s done, the bird has to be cooked very slowly. A fist-sized quail might take twenty-five minutes. A grouse might take forty-five. A duck, an hour. It goes by feel, and the only way to get the feel is by doing it. And if you get impatient while you’re at it, remind yourself that you’re trying to do something that 99 percent of Americans can’t do. After all, if it was easy, you’d already know how.