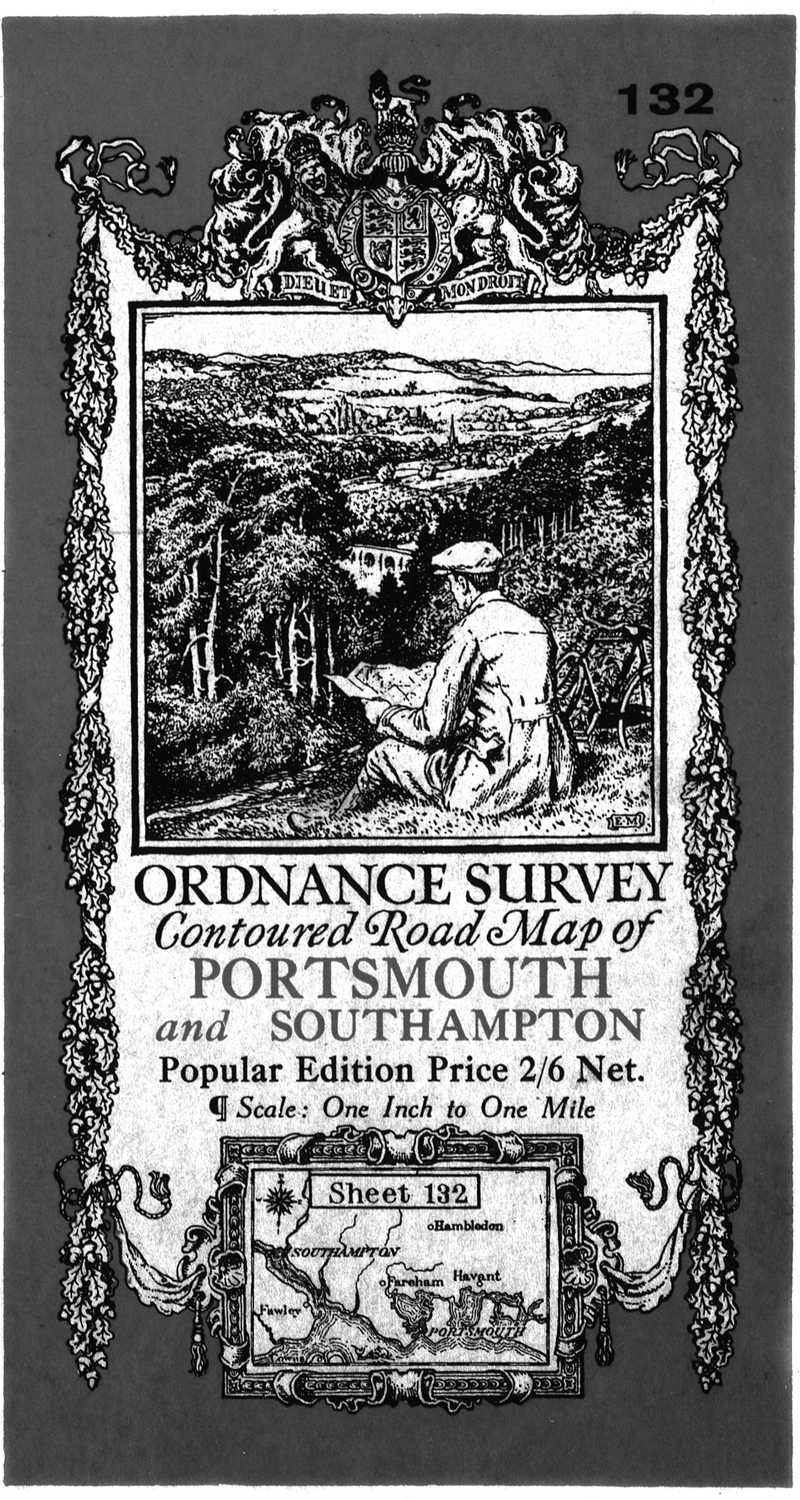

The original index map for the OS 1:50 000 series: there’s Aysgarth, but no Sheffield

3. EVERY NODULE AND BOBBLE

Ordnance Survey maps in all their shapes and sizes are the most beautiful manifestation of twentieth-century British functional design. Ever since I can remember, I have spent stolen moments, wasted evenings and secret hours studying the mystery and beauty of the Ordnance Survey maps of these islands. The concrete trig points that had originally been used in their creation became almost as powerful in mystical properties for me as standing stones.

˜ Bill Drummond, 45

Grimsby and Cleethorpes. Could there be a more inauspicious debut to a lifetime’s obsession? It was 1974 and the Ordnance Survey had just published its first swathe of new 1:50 000 maps, the metric replacement for the longstanding, much-loved one-inch system that had divided the country since the very first map in 1801. Whether it was their eye-catching colour (a goutish pinky-purple) or stark 1970s visual functionality, I don’t know, but as soon as I saw the new maps in W. H. Smith, I was hooked. I wanted them, and before I discovered how easy they were to steal, I was even prepared to save up my pocket money to get them. The going rate in our family was 2p for every year of your age, earning me a princely 14p every week. The maps were 65p each, so it took some saving—and some serious creeping to grandparents.

The 1:50 000 series (the ‘Landranger’ title only appeared in 1979) is the best range of general-use maps in the world. The whole of Great Britain is carved into 204 squares, each one a 40 × 40 km portrait of its patch of land. The variety is breathtaking: from map number 176 (West London), which is covered in the dense stipple of cheek-by-jowl population, covering the homes of perhaps 4-5 million people, to map number 31 (Barra & South Uist, Vatersay & Eriskay), where nine-tenths of the map is pale blue sea, and the rest just a few straggling islands of the Outer Hebrides, home to no more than a couple of hundred hardy souls.

I love every aspect of these maps: the clarity and efficient good sense of their colour scheme, their neat typography and lucid symbolism, the fact that they are at precisely the right scale to include every lane, track, path and farmhouse, every nodule and bobble of the landscape, yet cover a sufficiently large area to afford us a one-glance take on the topography of a substantial part of the country. Even the 1970s cover plan, a stylised square summarising the area to be explored within, has a pleasing visual economy, the size of the settlements upon it indicated by the depth of boldness of the type: darkest for the largest towns through to ghostly light for the villages. In the early days of the new series, before the marketing men decided to plaster the cover with a tourist board shot of somewhere on the map, the cover plan filled the map’s purple front: bold, clean and perfectly in keeping with the times. A lifelong OS collector-turned-dealer told me of the ‘moment of conversion’ that ignited his passion on unfolding a One Inch map for the very first time nearly half a century before, his captivation with the beauty and elegance of an Ordnance Survey map. Most OS aficionados can remember their own such moments of epiphany, when a lifetime’s love was, in an explosive moment of clarity, mapped out before them. And so very well mapped, at that.

The modernist mania for streamlining was evident in the new 1:50 000 map series, and not just in the cool lines and clear typeface of the covers. One of the all-new features of the maps was that everything was metric. The old one-inch (to one mile) scale, itself a masterstroke of simplicity, translated in metric terms to the rather more cumbersome 1:63 360. Expanding the scale slightly meant that the maps looked less crowded, and that each grid square, an orderly 2 × 2 cm, represented one kilometre. Not that you ever heard anyone refer to them as the ‘2 cm to 1 km’ series. It was—and is still—the ‘one and a quarter inches to the mile’.

Contours had to be translated into metric measurements too, and this produced one of the series’ daftest anomalies that remained obstinately in place for years, until the whole country’s height differentials could be re-surveyed and re-plotted at ten-metre intervals. As the key next to the map put it: ‘Contour values are given to the nearest metre. The vertical interval is, however, 50 feet.’ In other words, contours were merely renumbered metrically, making the gap between them a decidedly forgettable 15.24 metres. Thus, instead of a hill rising through 50, 100, 150, 200 feet and so on, it was now growing through 15, 30, 46, 61 and 76 metres. Things got even sillier the higher you went. Then there was the potential confusion in some of these odd contour measurements: 61, 91, 168, 686, 869, 899, 991 and 1,006 metre lines could all be misread upside down. Therefore it was decreed that such figures could only be placed on contours on the south-facing slopes, so that the numbers would be the right way up. As a result, you had to follow your finger round an awfully long way on some of the hills, the higher ones in particular. That said, anyone who thought that there were contour lines of 9,001 metres to be found in Britain should have been banned from going anywhere near a map.

There were very few contours on Grimsby & Cleethorpes, 1:50 000 map number 113. This really was the very first map that I frittered away my pocket money on, at the tender age of seven. I took it into school, hoping to impress everyone. Unsurprisingly, the ploy failed; as I unfurled the portrait of distant Humberside to a small crowd, there was puzzled silence and then a small voice piped up, ‘So where’s Kiddy on that, then?’ The realisation that others failed to share my enthusiasm, or even to understand the concept that there was a whole big country out there that Kidderminster wasn’t a part of, was crushing, but it didn’t deter me. Before long, I’d saved up for my second OS map, right down the other end of England, number 189 (Ashford & Romney Marsh). I wasn’t especially interested in seeing close-up details of my own neck of the woods, or even any of the places that I knew. Thirtyfive years later, I’ve still never been to Grimsby, Cleethorpes or Ashford, but they were the first places I wanted to scrutinise on the map, to wander around in my febrile imagination.

Hard though it may be to believe, those first two maps represented a glimpse of the exotic. And it was a very specific kind of exoticism that appealed to me. Even at that early age, I had become fascinated by endof-the-world places and communities, set at the far end of bumpy tracks and sliding lethargically into the sea under lowering, leaden skies. Part of it was undoubtedly the call of the ocean. The sea holds a very specific place in the psyche of a Midlander. When you only see it once or twice a year, and that’s when you’re on holiday and there are endless ice creams and amusement arcades to accompany it, even the steely Scarborough briny comes to represent all that is exciting, infinite and free.

Of all the 11,073 miles of British coastline (19,491 if you include the offshore islands), the two areas that I first chose to own by proxy of a map seem strangely perverse, even now and even to me. This is not the Kiss Me Quick seaside; more the Wring Me Out and Leave Me For Dead coastline. But each of those first two maps held one feature that enthralled my besotted mind. On the Grimsby & Cleethorpes map, it was the long spit of land known as Spurn Head at the mouth of the River Humber, while on Ashford & Romney Marsh, it was the ethereal swell of marsh, bog and nuclear power station known as Dungeness. Spurn Head and Dungeness. Even the names sound vaguely suicidal.

Hours I spent poring over those obscure corners of this island. Nowadays, a precocious seven-year-old with similar tastes would merely tap the names into Google, and find himself presented almost immediately with galleries of images and reams of facts. Nothing so instant in 1974. It was left to my overheated mind to create images of these weird-looking landscapes. On the map, the lack of contours, the ruler-straight lanes and irrigation ditches, the banks of shingle and the odd names all conjured up a misty melancholy seeping over the bleak countryside like an unseen plague. Back in my Midlands bedroom, I hugged these unknown, unknowable places to my chest and swore that one day I’d get to meet them.

Spurn Head I managed to tick off my list decades ago, although it took until very recently to make it to Dungeness. My love affair with end-of-the-world landscapes has continued into adulthood, and, in my twenties, I was fortunate enough to have a good friend who shared this strange passion. Jim and I would borrow a car for the weekend and head off to places whose sole criterion for us was that they just looked weird on the map. Hours we spent poring over my OS collection, trying to find just the right balance of oddities in any one place. Hence the Isle of Thanet, the Suffolk coast, Portland, the Forest of Dean, the Wash, the Isle of Wight and the Humber estuary all came under our critical gaze at some point or other. Best were those places that not only afforded the opportunity to look out over marsh and mudflat, but also gave us the chance to hang out in its dead-end urban twin, the out-of-season British seaside resort. Thus Skegness was a great base for the Wash trip, Thanet gave us chance to be depressed by Margate long before Tracey Emin gentrified it, and Bridlington was a superbly moribund HQ for that ultimate trip to my long-awaited paramour, Spurn Head.

Spurn was no disappointment. In fact, I can recommend it as the ultimate British road-movie destination for that nowhere-to-run explosive climax. Whichever way you come at it, you will have to travel through miles of pancake-flat scenery, where the sea frets roll in and blanket out the grim farmhouses, lonely church spires and caravan parks clinging to cliff edges. Occasionally, just to heighten the surrealism of the scene, the dim shape of an ocean-going tanker will glide by in the distance, looking as if it is ploughing through the black fields.

The best route to Spurn Head is along the Holderness coast to its north. This is the fastest-eroding coastline in Europe, receding at an average of two metres per year, although single-occasion erosions of six metres and more have been recorded. Over the past few centuries, dozens of villages have fallen over the edge and been wiped from the map altogether: a roll-call includes such fine-sounding settlements as Owthorne, Auburn, Cowden Parva and the particularly appealing Hartburn. Today’s Holderness villages are on Death Row. Official policy is quietly to abandon places like Kilnsea, Easington, Holmpton, Rolston, Atwick and Barmsden to the mercy of the sea. The coast’s two main towns, Hornsea and Withernsea, have coastal defence systems in place, although they still face some uncertainty, and periodic pieces appear in the local press wailing about unsellable houses and plummeting property prices. Such are the forces of nature in these parts, however, that the comparative security of these two towns only heightens the misery of others: if one part of this dynamic coastline is artificially shored up, it only means that some other part, a bit further south, will be eroded all the more. You can imagine what that would do for community harmony and the length of debates in the local council chamber.

As ever, their misery is our fascination, for this is a weird, woeful and riveting place. Jim and I drove slowly down from Bridlington, taking the odd small lane that headed eastwards towards the sea and, on numerous occasions, finding it disappearing over the edge of the cliff. Shards of broken tarmac pointed out to sea, abandoned houses teetered on the brink of the drop, seabirds swooped and shrilled a maritime last post. The frailty and the melancholy only increased as we headed further south towards Spurn Head. In every sense of the phrase, it blew me away.

Over the past millennium, there have been five different Spurn Heads, each one slightly to the west of its predecessor. The cycle of the spit’s growth, increasing fragility and then ultimate destruction and regrouping, tends to do a full circle about every two hundred and fifty years, meaning that the current Spurn Head is living on borrowed time. The slender neck of the four-mile-long spit is in constant danger of being breached.

Driving down this tiny thread of land is like walking a tightrope in a gale. The concrete road is poor and rutted, with drifts of sand blocking the way and sea spume whacking your windscreen like a scorned lover. At times, the road is virtually all there is between the two banks of angry, choppy sea falling away on either side. There is no safety net. At the end of the spit are a few brutal government outposts: a lifeboat station, with Britain’s only permanently sited crew, a lighthouse and the Vessel Traffic Service Centre, tracking the lumbering great tankers heading up the Humber to Immingham, whose Meccano-like gas terminals can be seen blazing across the muddy estuary. All are blasted by gale-force winds for most of the time. When Jim and I pitched up, it was a fine, calm day in dear old Brid, but by the time we got to the end of the spit, it took every ounce of shoulder power just to get the car doors open. We stood around on the beach for a while, until our eyeballs started to pop and tears were flowing from the whipping, sand-blasting laceration of the wind—all in all, about five minutes. It is one of the ugliest, rawest places of beauty I’ve ever experienced. And it is quite wonderful. Twenty years it had taken from running my eager finger along my first Ordnance Survey to standing on the point itself, but it was worth every minute of the wait. We headed back to Brid, and I was a man fulfilled.

I recently bought a new version of that initial map to see how my first love had fared over the past third of a century. There’s no swifter way of getting a handle on the huge changes in the layout of Britain over the last couple of generations than by comparing Ordnance Survey sheets of the same area, especially one as varied, in its rural, urban, industrial and coastal mix, as the Grimsby & Cleethorpes 1:50 000. Poor old Cleethorpes has got the push for starters, as the map is now titled plain Grimsby, with Louth and Market Rasen as the smaller sub-heads. That’s despite the fact that Cleethorpes is one of the towns on the map that has ballooned the most between the 1970s and the 2000s; whole fringes of squiggly new housing estates are plugged into every available corner, including one laid across what, three decades earlier, is marked on the map as a marsh. The town’s expansion has been positively slimline, however, in comparison with some of the villages south of the Humber. Our national hunger for the pastoral life seems unstoppable, even if villages here, such as Caistor, Waltham and Holton-le-Cley, are little more than modern, steroid-packed doughnuts throttling the original settlements.

In 1974, the new Ordnance Survey series’ pièce de résistance was in mapping, for the first time, the sleek new counties that had arrived in April of that year. Here, we see Humberside make its cartographic debut; born in the hope of uniting the Yorkshire and Lincolnshire banks of the Humber, despite the fact that, for the first seven years of the county’s life, the only way between them was a creaky ferry or a huge diversion inland—the road journey from Grimsby to the Humberside County Council headquarters at Beverley was almost one hundred miles. The ferry’s replacement, the Humber Bridge, may well have opened as the largest single-span bridge on the planet, but it was costly to cross and did little more to gel the county together, except as a too-little, too-late symbol and one that, like the county itself, proved to be something of a white elephant. Small wonder: the bridge had only been built as one of the most blatant bribes ever served up by politicians.

The announcement of the project came in the middle of the campaign for the Hull North by-election of January 1966. The death of Labour MP Henry Solomons, who’d wrested the seat from the Conservatives with the tiniest majority in the general election of October 1964, had cut Harold Wilson’s parliamentary majority to just one. Wilson threw everything at the by-election campaign, most startlingly the promise of the Humber Bridge. It worked; Labour upped its majority to over five thousand, enough of a swing to persuade Wilson to call another general election and secure a more comfortable majority.

Antipathy towards Humberside grew locally and, indeed, nationally: it became the Page Three girl of the We Want Our Old Counties Back movement, and was regularly cited as the most steadfast proof that the 1974 changes had been the victory of bloodless bureaucrats over local loyalty and natural identity. Many protests, reviews, commissions and changes later, we eagerly turn to the new map to see what civic pride has been restored to the area now that the county of Humberside has been thoroughly dumped. And that’s when you notice something a little odd, for the reviled county border has not shifted an inch, only the names have been changed. The ghostly shape of the despised authority is entirely intact on the map, but instead of showing the border between the counties of Humberside and Lincolnshire, it now details the split between the two-tier county of Lincolnshire (further divided into the district council divisions of East Lindsey and West Lindsey) and the unitary authorities of North Lincolnshire, North-East Lincolnshire and, across the Humber, the East Riding of Yorkshire. Glad they cleared that up so effectively.

The most startling difference between the two maps, however, is their portrait of the merciless rise of tourism as the mainstay of our economy. In 1974, there was not one museum marked on the map. Its 2006 version is awash with the blue hatching used to denote ‘selected places of tourist interest’, and shows four museums, three visitor centres, one theme park, two country parks, a zoo, an ‘Animal Gardens’ and numerous other attractions of varying degrees of dubiousness. There’s also the inevitable heritage steam railway carved out of a tiny fragment of line closed in the Beeching cuts of the 1960s. It has only one station, Ludborough, and currently your £4.50 ticket (£5 on special ‘1940s Days’) buys you a nine-hundred-yard journey from there, through a couple of pancake-flat fields, before stopping and then being gently pulled back to where you started. The middle of nowhere return, please. Almost twenty years after this thrilling ride was opened, the Lincolnshire Wolds Railway is hoping to open a second station at North Thoresby, a whole mile and a half from Ludborough. Who’d want to go to Florida with that kind of excitement on your doorstep? In terms of the map, the fact that these pointless excuses for both railways and tourist attractions are shown with exactly the same symbology as a real railway, connecting real places, is something that pains me to see on a modern OS map. On the 1:50 000, the Lincolnshire Wolds Railway, with its 1.7 inches of track and solitary  symbol, looks frankly risible. There should be a special symbol for these toy trains that doesn’t confuse them with the real thing: my suggestion would be a pictogram of a grinning old man dragging a reluctant grandson along. Such an image could be misconstrued, I realise, but perhaps not entirely without justification.

symbol, looks frankly risible. There should be a special symbol for these toy trains that doesn’t confuse them with the real thing: my suggestion would be a pictogram of a grinning old man dragging a reluctant grandson along. Such an image could be misconstrued, I realise, but perhaps not entirely without justification.

It was only in 2007 that I finally made it to the location of the second OS map that I’d bought over thirty years earlier: number 189, Ashford & Romney Marsh, purchased in order to gaze lovingly at another mysterious coastal protuberance, Dungeness. I’d go so far as to say that it is quite possibly the most awe-inducing place I have ever visited in Britain. Dungeness plays with all five senses: the sight of the endless skies, seas and shingle, the background hum and plunk of the nuclear power stations, the slap of the wind, the sweet wafts of honey from the sea kale poking defiantly out of the pebbles, the tang of salt. Strewn around the headland are a few dozen shacks, huts and railway carriages, brought here to their graveyard after the First World War as wind-blasted homes for fishermen and rock-crushers, historically, the two sole occupations available in Dungeness. Then they cost a tenner each; today, thanks to Derek Jarman and the succession of dropouts and artists who followed in his slipstream, they go for around two hundred grand apiece.

Aside from their novelty beauty, their most startling attribute is that there is not one fence between them, just a succession of driftwood and debris gardens strewn among the shingle for anyone to amble through; as Jarman put it, ‘My garden’s boundaries are the horizon.’ Just up the road, in the clipped little resorts of Lydd-on-Sea, Littlestone and Greatstone, normal Kentish service is resumed in the brick bungalows, security warnings and picket fences which serve only to exaggerate Dungeness’s scattergun democracy. It is impossible to be ambivalent about the place: you either despise its squally shabbiness or adore it for the very same reason. I’m firmly in the latter camp—even the twin nuclear plants, with their attendant forests of pylons, failed to offend me in the slightest, so naturally did they seem to sit in this quite crazy landscape. Indeed, they provide one of the Ness’s most pleasingly surreal sights in the patch of boiling sea where the outflows disgorge, attracting shoals of fish and clouds of screaming birds.

Malcolm Saville, that upright, uptight children’s author that so appealed to me as a youngster thanks to the maps in his books, based some of his Lone Pine adventure stories in nearby Rye, and Dungeness featured in his 1951 book The Elusive Grasshopper. Saville hated the place, as was clear from his deathless prose:

Some days later Jon tried to describe Dungeness to his mother and found it very difficult, although it was little more than a desert of shingle which had been made even uglier by slovenly and haphazard building of bungalows, shacks and old railway coaches.…[It was] a horrid sight and even on this sunny afternoon Jon felt that this outpost was both curious and uncanny.

To those of a more iconoclastic bent, the place acts as a magnet. More than perhaps anywhere in England, Dungeness deserves the clichéd epithet of being ‘at the end of the world’, which is surely what draws so many of life’s outsiders to it. This is land that was, not so long ago, sea, and it could so easily be again, its very insubstantiality a balm and a redoubt to those weary of the fortress mentality that so characterises all too much of our landscape. Dungeness is The Last of England, the name that Derek Jarman gave his raging cinematic riposte to the Thatcher years, some of which was shot on location here. Jarman may be gone, but anarchic playwright Snoo Wilson still has a shack there, and the late comedienne Linda Smith chose to have her ashes scattered at Dungeness, partly in honour of having located the perfect crab sandwich in the miniature railway café there a few years earlier.

That night, I lay in my camper van right up against the power station’s perimeter fence, bathed in the plant’s arc lights and dreaming through the constant fizz and crackle of its reactors. For an hour, I scrutinised the map that I’d bought so many years earlier and that had first ignited the urge to see this mad place. The map had hinted at all the eccentricities and delights of the area, and I was thrilled that I’d spotted them so readily and that they’d been so gloriously confirmed in reality. Ashford & Romney Marsh is a beautiful example of the Ordnance Survey at its finest, especially in its portrayal of the two utterly different Kents, divided by the old sea cliffs and the Royal Military Canal at their base. To the north and west, the gentle contours and rippling orchards of the Downs and the Weald; to the south and east, the shaggy flatlands, ditches and shingle of Romney Marsh and Dungeness. The marsh is a land of spectres, where nothing is quite as it seems. Villages have vanished, changed their names and moved, leaving just crumbling church ruins and stagnant pools in remote fields.

It was pleasing to discover that the area had had a significant role in the Ordnance Survey’s birth. This was the very first part of Britain mapped by the OS, its inaugural Kent sheet appearing in 1801. When the Survey’s double centenary was celebrated in 1991, the commemorative Royal Mail stamps nodded to this piece of OS history, showing four maps of the marshside village of Hamstreet through the ages. Even earlier, in the 1780s, the area had played a significant part in the genesis of the OS. Once William Roy had successfully plotted his base line across Hounslow Heath, a series of triangles between London and the Kent coast needed to be measured in order to secure the accurate positioning of the London and Paris meridians. The main base line for verification was across Romney Marsh, from the village of Ruckinge to High Nook on the seawall at Dymchurch, the region’s flatness being its principal appeal. It was not a happy project: Roy himself writes that it was an ‘operation of so delicate and difficult a nature’, thanks to ‘the country so much intersected by ditches, and where there were so many ponds of water to be avoided’. Furthermore, thanks to delays in the delivery of the apparatus, the measuring operation didn’t begin until 17 October 1787, continuing for two months, through weather that Roy wearily described as ‘tempestuous’.

To be fair, Roy was not a well man, and by the time the Ordnance Survey was officially born on 21 June 1791, he had been dead a year. The Survey’s birth date is given as the day on which it was first granted expenditure from the public purse—£373 14s to pay for Jesse Ramsden’s second, superior theodolite. Ramsden’s original instrument, whose tardy progress had caused William Roy such apoplexy, was blown to bits in a Second World War bombing raid on the OS headquarters in Southampton, but his second one can still be seen, in all its enormous, intricate glory, in the Science Museum in London. It’s a sweet apposition that the Survey was born on the summer solstice, the day of greatest daylight, for its work has so gloriously illuminated British topography, history and culture ever since.

For us map devotees, the Ordnance Survey is the high altar of our cartographic temple. No other mapping agency comes close, either at home or abroad; the maps it produces are regularly, and deservedly, cited as the finest in the world, and not just by Brits either. Such adulation is a comparatively modern phenomenon, however, for it hasn’t always been that way. At certain times in its history, the OS has been hopelessly out of kilter with the needs of its many masters, be they the map-buying public, politicians, the Exchequer or, these days, those who campaign hard for the release of topographical data from the OS’s tight clutches, for it’s not unreasonable to say that the publicly funded Ordnance Survey has historically had a near monopoly on the lie of the land, and it’s not been afraid to use or defend it. This has been a running sore since the earliest days. In 1816, Major-General William Mudge, Superintendent of the Survey, huffed that ‘an idea has gone abroad among the Mapsellers of London that as a portion of the Public, at whose expense the Ordnance Survey is carried on, they have a right to reduce from and publish Copies of the Ordnance Survey on Scales to their own convenience’. As a state agency, the Survey has always been able to commandeer the ears of government, even having copyright laws bent in its favour.

One paymaster that the Ordnance Survey has never seriously fallen out with is the defence establishment. For most of its first hundred years, OS top brass and their modus operandi were entirely military. The maps were also available to the public from the beginning, but the right was periodically revoked at times of national emergency, particularly in withdrawing from sale maps of the south coast on those occasions when Napoleon was peering avariciously across the Channel. The bans never lasted long, however, and a growing band of civilian enthusiasts for the new maps beat a path to the door of the only two outlets for their sale: the Ordnance Survey’s own headquarters in the Tower of London, and Geographer Royal William Faden’s business in Charing Cross.

This unswerving loyalty to the defence of the realm has had some noticeable effects. Although the first tranche of map-making that came to result in the OS was William Roy’s mid-eighteenth-century survey of the Scottish Highlands, there’s been an institutional bias against the north of Britain since then that has permeated down the centuries, despite the perception among those of a certain mindset that the precise opposite was the case. In an 1883 House of Lords debate, Lord Salisbury, soon to begin his first term as Prime Minister, boomed his complaints about the Ordnance Survey’s progress with its six-inchesto-the-mile survey of the entire realm:

They seemed to have gone on the principle of serving first those parts of the Kingdom which were the most disagreeable to the Government, and which were not in so much need of the maps as England. The most disagreeable part of the Three Kingdoms was Ireland, and, therefore, Ireland had a splendid map. Next to Ireland, Scotland was the most disagreeable part of the country to the Government, and, consequently, Scotland had a map; but poor, meek, humble, submissive England was necessarily left to the last.

In truth, the first parts of the country that demanded maps from the OS were the coasts of southern England, those most vulnerable to invasion from the Continent. Since then, almost every new imprint of OS maps has followed suit, with plans of southern parts of Britain being published sometimes long before those of the north. This happened not just with the very first maps, but the old series of One Inch maps in the mid nineteenth century and then with the large-scale 1:2500 series that formed the basis of all detailed mapping, in which some of the plans of rural Scotland first appeared more than forty years after their southern counterparts. Even in modern times, the trend has continued, albeit less dramatically: the 1:25 000 Explorer maps gradually covered the country from the bottom up, while the launch of the new 1:50 000 series, the flagship of the Survey, was split into two, with the southern half of Britain, below a line from Lancaster to Bridlington, being published in 1974, the remainder in 1976. Two years was a long time to wait for a seven-year-old: I was through the doors of W. H. Smith at opening time on the day the new northern maps were due to be published, and, to my delight, they’d arrived. To me, it was the Harry Potter launch of its day, even if I was the only one in the queue. I’d been frantically saving up for the big event and bought three of their North Yorkshire sheets on the spot, racing back home to spend long hours in my bedroom scrutinising the places that we visited every year on our annual jaunt to Aunty Molly’s in Scarborough.

This inherent southern bent doesn’t come as any surprise in an organisation incubated within the British military establishment and firmly rooted in the south of England. The forces, from their parade grounds in Sandhurst, Horse Guards and Winchester, have long looked at the north and the west of our islands as distant, stroppy outposts of the Empire, full of tetchy natives in inhospitable terrain. All directorgenerals of the OS, from the very beginning and almost to the turn of the twenty-first century, came from a pool of colonels, brigadiers and major-generals. The very first DG without military training was Professor David Rhind, who took up his post only in 1992.

Inevitably, the maps have reflected such influences. Even now, and even when there is absolutely no trace to be seen on the ground, the site of a battlefield is enthusiastically marked with its striking crossed swords motif. By contrast, as OS historian Richard Oliver has tartly put it, ‘no one would guess from an OS map that there was such a thing as labour history’. Military and ecclesiastical remains are the only ones worth marking, it would seem, which speaks volumes about the Ordnance Survey’s historic view of the land and the cultural influences woven into it.

From those early days, it’s hard not to picture extravagantly moustachioed OS types marching over the country in pursuit of their information, bringing with them attitudes that reeked of the public school and the parade ground. Such a scenario even made it as a mediocre movie, The Englishman Who Went Up a Hill, But Came Down a Mountain, from 1995, which told the tale of an Edwardian map surveyor despatched to gather topographical information about a small Welsh village, whose inhabitants are horrified to find out that their beloved mountain will have to be reclassified as a hill, as it falls a few feet short of the requisite height. The comedy, such as it was, came from the misunderstandings between the terribly English officer (the inevitable Hugh Grant at his most bumbling and floppy-haired) and the conniving natives, determined to delay him long enough to enable them to shore up their hill so that it squeaked past the necessary threshold. And—wouldn’t you know it—the enforced delay is just long enough for the strait-laced surveyor to fall head over heels for a local ravenhaired lovely.

Victorian imperial attitudes of geographic and cultural rank permeate all aspects of the Ordnance Survey’s development. Surveyors, when heading out into the field, were issued with detailed instructions on what to look for and how to present it on the maps. The names of places could prove particularly thorny, laden as they were with local custom, variant spellings, even variant languages. The OS Field Guide of 1905 cut through such potential pitfalls with nary a blink:

For names generally the following are the best individual authorities, and should be taken in the order given: Owners of property; estate agents; clergymen, postmasters and schoolmasters, if they have been some time in the district; rate collectors; road surveyors; borough and county surveyors; gentlemen residing in the district; Local Government Board Orders; local histories; good directories…Respectable inhabitants of some position should be consulted. Small farmers or cottagers are not to be depended on, even for the names of the places they occupy, especially as to the spelling, but a well-educated and intelligent occupier is, of course, a good authority.

We map addicts have to forgive the Ordnance Survey its inevitable pomposity, for no one could emerge from such a deeply Establishment background entirely unscathed. The organisation has, after all, been pretty thoroughly decontaminated, the band of the Royal Engineers performing a ceremony of Beating the Retreat in the Southampton headquarters car park in October 1983, an occasion intended to symbolise the cutting of the military apron strings. The last four director-generals have all been from civilian backgrounds, the current DG, since 2000, representing a decisive change as the first woman to hold the post and from a background far more relevant to today’s OS: publishing and information technology. This DG, Vanessa Lawrence, has unquestionably softened the edges of the organisation, spearheading cuddly new policies such as giving a free Ordnance Survey map to every eleven-year-old in the country. Evidently, I was just a little ahead of the times with my map larceny of the early 1980s.

Today’s OS is a very different beast from its earlier incarnations, even that of only thirty years ago. The appointment of Vanessa Lawrence as Director-General is the most obvious symbol of the new, digitally oriented, more feminised OS, but it is far more than a marketing trompe l’œil. When, in 2007, after thirty-three years of collecting OS maps, I finally made it to the headquarters in Southampton, I was amazed to see the sheer quantity of women working there, many in senior roles. More than that: there was a decidedly, and unexpectedly, matronly atmosphere to the place, much augmented by the fact that many of the employees hail from ‘OS families’, third- and even fourthgeneration workers whose roots in the organisation, and loyalty to it, delve down extremely deep.

It’s partly a Southampton thing, for a large, prestigious organisation in a smallish city is far more prominent than it would have been had the Survey remained in London. As a child collector of OS maps, its very address became suffused with a certain exoticism, which is no mean feat considering the mundanity of its location at Romsey Road, Maybush, Southampton. I had absolutely no idea what sort of a place Southampton might be, but I gazed at it on the maps, spread so becomingly along the north shore of its estuary, and dreamed of seeing it one day. In my head, it was a city of swaggering sophistication, boosted by the fact that the only other time it ever flickered across my radar was as the launch pad of the QE2 or the glamorous, doomed HMS Titanic. Furthermore, it was in swanky Hampshire, which, from a satellite town of the West Midlands, oozed prosperity and ponypaddock class. When I finally got there in my early twenties, I couldn’t quite believe that the Coventry-with-seagulls before me could possibly be this hallowed Mecca.

A rough old bird Southampton might be, whose rivalry with Portsmouth must constitute the nastiest spat between neighbouring towns anywhere in Britain, but a pretty port is usually a dull marina these days, so long may it remain as dowdy and grumpy as it is. The city has, however, proved to be a perfect home for the Ordnance Survey: the geek and the plain lass rather fell for each other, though neither expected to. The move was forced on the young OS by a fire in its Tower of London headquarters at Halloween in 1841. Southampton was proposed only because there was a big, empty government building there (the former Royal Military Asylum): the OS mandarins were horrified by the idea. A century later, the Southampton site was badly bombed as a strategic target in the Second World War and the Survey was scattered around temporary sites across the country. After the war, the government proposed that the organisation should leave such a vulnerable spot on the south coast and relocate to Northamptonshire. The OS, despite its battering, was hearing none of it, and bludgeoned successive governments until they gave in and built it a new HQ in its, by now, firmly home city. And still the love affair continues. Generations of Southampton families are woven into the fabric of the OS; the city is deeply proud of its status as the organisation’s nest.

On my visit, this all came as quite a shock, especially after first seeing the HQ building (officially William Roy House). It’s a vast 1960s monolith, built to house OS at a time when its payroll was approaching five thousand. Today, the building houses fewer than a third of that number; whole wings, floors and corridors lie empty and echoing. I’ve been in so many buildings like this: regional newspaper offices, TV studios, council and company headquarters—all constructed in the heyday of full employment and modernist chutzpah, but overtaken since by the digital revolution and slice after slice of cutbacks, the prize-winning architecture springing leaks, and asbestos alerts on an almost weekly basis. They’re the kind of buildings that normally guarantee a migraine within half an hour of entry, and—like the Survey’s HQ—they’re all gradually being abandoned and demolished. Yet despite the unprepossessing surroundings, I’ve never come across a massive office block with such a genuinely cheerful atmosphere as the Ordnance Survey’s. People seemed to adore their jobs there and, unless the management had been slipping serotonin into the water coolers, it all seemed wholly authentic.

I might, however, be colouring the experience with my own delirium. Visiting the headquarters of the Ordnance Survey, an organisation that I’d been in love with for a third of a century, was seventh heaven. Their press office had kindly sorted me out with a day of seeing how their whole operation—from initial survey to printing and distribution of the maps—worked; it would not be an exaggeration to say that it was one of the most blissful days of my life. At last, I could have in-depth conversations with people who cared even more than I did about these beautiful maps. No cartographic subject was too persnickety for these folk, no one’s eyes glazed over at detailed discussion about the symbols and colours on the maps, the cover images or the names chosen to market them.

Most illuminating was a long chat with the Product Manager, responsible for the paper-map output of the OS. Startlingly, this accounts for less than ten per cent of Ordnance Survey’s income these days, and the figure is falling rapidly as the demand for digital data grows by the day. The market for the traditional OS map is ageing and shrinking, or, as she put it, ‘We know exactly where we stand. There is something distinctly Enid Blyton about the Ordnance Survey. It’s all very Middle England, National Trust and Radio 4.’ I thought about trying to contradict her, but quickly realised that I couldn’t be more firmly in that camp than if I was sat in The Bull at Ambridge, quaffing a ginger beer and consulting the OS Explorer, Felpersham & the Am Valley, for local NT properties to visit. Even the maps’ names hint at the target audience: is it pure coincidence that the flagship Landranger series sounds like a hybrid of a Land Rover and a Range Rover? Are we to expect a new series called the Golden Retriever?

Ordnance Survey knows its demographic intimately, for the simple reason that it hears from them on a very regular basis. Just as any change to the Radio 4 schedule elicits howls of protest in the Shires, so does any slight tinkering with the maps. In the early 2000s, OS briefly removed the borders of national parks from the 1:25 000 Explorer maps; a huge outcry soon saw that decision reversed. One of the cartographers told me that, because many of the 1:50 000 Landranger maps were in danger of becoming too cluttered, they would have liked to take the footpaths and other rights of way off them, but knew that the resultant palaver would be terrible PR and more trouble than it was worth. The most thunder-striking example came from a couple of years ago, when the tankard symbol, for a country pub, was modified on the Explorer maps. The level of beer in the glass dropped slightly in the revised version, and quite a few people actually wrote in to OS complaining that they were being short-changed of their pint. Granted, this could have been a prime example of Home Counties humour, the ‘And Finally…’ of the Telegraph letters page, but hearing it made me feel ashamed to realise that I am but a novice in the map-addict stakes: not only had I failed to notice the change, I couldn’t muster any feeling about it either way. I’d love to see the reaction if OS announced that the cheery tankard was, in fact, a half-litre, not a pint, or, even better, that it was being abolished altogether in favour of a sponsored pictogram of a Bacardi Breezer. Oxfordshire would implode.

Symbols and boundaries on the map, or lack of them, cause more trouble and indignant letters than just about anything else to the Ordnance Survey. There is constant and unremitting pressure on the organisation to add yet more features to every map, particularly from the tourism industry, which wants dedicated new symbols for every hokey craft centre and artist’s studio flogging winsome watercolours of the locale. OS is mindful that the vast majority of paper maps these days are bought for leisure purposes, which is why the Landrangers and Explorers are already crammed full of blue symbols for what seems to be every conceivable tourist attraction or service. But the 1:50 000 Landranger series, in particular, is already at the point where any more symbols will begin seriously to detract from the map’s utility, for some of the maps, particularly in the more traditional holiday areas, are full to bursting. Currency—keeping up to date with topographical changes—is the principal watchword of the map-makers, but clarity comes a close second, and that is increasingly under threat.

More and more, Ordnance Survey is finding itself under pressure to expand the repertoire of what is mapped, not from the ordinary map addict, but from the hired professionals. Tourist boards are the main culprits; they won’t rest until the maps are as stuffed with blue symbols as the roads are with brown signs inviting car drivers to hurtle between one disappointing leisure experience and the next. The exponential growth in the brown-sign industry is a clear warning to map-makers not to go the same way. Twenty years ago, there was a threshold of visitor numbers to qualify for the signs, but now it’s something of a free-for-all, as well as being a nice little earner for the Highways Agency and local authorities. They promote a grimly reductive experience of the country, where practically everywhere can be—and is—pared down to a meaningless catch-all, like the ubiquitous ‘Historic Market Town’. Where isn’t? It was back in the early 1990s that the Queen reportedly blew a fuse when she first saw the huge sign on the M4 pointing to ‘Windsor: Royalty & Empire’. Things have got a whole lot worse since then, Ma’am.

The latest ruckus about what should and should not be marked on Ordnance Survey maps came in 2007, when a PR company, knowing all too well how many column inches could be crowbarred out of the credulous regional press, rounded up a handful of hungry MPs to shout about the lack of recognition for the fast-vanishing coal industry. The politicians and the snake-oil sellers combined as one to demand a new symbol on the OS maps for every site that had once been a pit, even if it had been entirely built over subsequently and there was no evidence of any mining to be found there now. They have a point: thanks to its inherently conservative heritage, the OS and industrial history make reluctant bedfellows, but it’s hard to see that this is the answer. How big did the mine have to be and how long did it have to function to warrant inclusion? And after coal mines, then what? According to the PR guff of the campaign, ‘It’s about marking the fruits of men, children and women’s labour. The injuries. The chronic illnesses. The culture. The history. The communities. The decimation. The demolition. The rejuvenation. The regeneration.’ So what about the often equally deadly quarries, mills, factories, armaments depots or harbours? Where do you stop? And how pleased would people be to find that, on the map, their housing estate is obliterated by a little blue symbol of a pithead wheel or a pickaxe, something screaming ‘potential subsidence’ to house-buyers and insurance companies?

Although Ordnance Survey issues maps and data in a dizzying range of different scales, the most exciting publications, from a map addict’s perspective, are the two principal paper-map series, the 1:50 000 Landrangers, successors to the gold standard that was the One Inch map, and the 1:25 000 Explorers, the hugely successful, and comparatively new, series at double the scale of the Landrangers. Maps at this larger scale only date from after the Second World War, and focused for many years solely on the most popular tourist regions. In 1970, by which time only 78 of the scheduled 1,400 sheets had been published in this series, Ordnance Survey proposed abandoning maps at this scale altogether, an idea that was only defeated by an outcry in Parliament and from the Ramblers’ Association. The complete national series of orange-covered Explorer maps was finally finished as recently as 2003, replacing the ragbag of Outdoor Leisure maps, largely of the national parks, together with the previous Pathfinder series, whose maps had covered only tiny areas. That the Explorer series has been welded together out of different previous editions is obvious in their strange, and sometimes inconsistent, numbering, as well as the very many shapes and sizes of the maps themselves: some are doublesided, some not and there are some very oddly shaped areas of coverage. A few of the Outdoor Leisure maps (now officially rebranded as Explorer OLs) are vast and double-sided, beautiful to look at if you can spread them out on the floor or a sufficiently large table, but downright exasperating if you need to turn them round in the passenger seat of a car or, even worse, on a wet, windy mountainside.

Despite being so comparatively new, over the past decade sales of the large-scale Explorer maps have far eclipsed those of the more established Landranger series. They have become the sexy new pin-ups, OS’s biggest seller—Explorer Map OL24, The Peak District: White Peak—shifting around 40,000 copies a year, over three times as many as the best-selling Landranger map, number 90, Penrith & Keswick, which covers a large tranche of the Lake District. It is these maps, not the pink 1:50 000 ones, that the OS has chosen to dole out for free to every eleven-year-old in the country, a scheme that, by its seventh year of operation in 2008, had seen 4.5 million maps distributed to schoolchildren as their own personal property, and which has led to a significant improvement in map literacy among the young. The Explorer maps are now the unquestioned brand leader for Ordnance Survey.

It’s not hard to see why. If tourism and leisure are the driving forces for paper-map sales these days, that almost always includes our national love of rambling, and the 1:25 000 range is the perfect map for that, peerless in its coverage of footpaths and other rights of way. This is, without doubt, the main reason for their success, amazing to consider when you remember that rights of way information has only been included on OS maps since 1960, and only patchily until very recently. The Explorers are also the smallest scale at which field boundaries are shown; this, when so much of the footpath network is badly signposted, blocked or inaccessible, is nigh on essential for a reducedstress hike. The series was also given a huge boost by the 2000 Countryside and Rights of Way (CRoW) Act, which opened up over two million acres of England and nearly a million in Wales as Open Access land. After much consultation, many quibbles and considerable drawing and redrawing of the maps, the scheme was finally launched in September 2004, with OS hurrying out a huge number of Explorer maps updated to show the accessible land in detail. And only the Explorer maps; Open Access land is not marked at all on the 1:50 000 series. The new maps sold in droves.

The long-awaited right to roam over such a large part of the country was greeted with massive enthusiasm in almost every quarter. Once again, it was the maps that brought the enormity of the change home: seeing great swathes of my local area in mid Wales suddenly marked as open to all was astounding and extremely exciting. At a stroke, the percentage of publicly accessible Welsh land had gone up from 4 to 22, almost a quarter. The map, and the countryside, would never look the same again.

Cause for celebration indeed, and not just for the generous spike in the sale of OS maps, but still sobering when compared with the situation in Scotland. You’ll notice that Ordnance Survey maps of Scotland do not plot either rights of way or Open Access land in the way that their English and Welsh counterparts do. They don’t have to, for Scotland has always had a far more democratic presumption of the right to roam than has ever been the case south of the border. This was augmented by the Scottish version of CRoW, the Land Reform (Scotland) Act of 2003, which enshrined in law principles of complete access to the countryside, and not just for walkers. In England and Wales, only a shade over 2 per cent of inland waterways have rights of access to them, despite the fact that no one actually ‘owns’ the water that flows in the rivers and streams, although they can lay claim to the riverbeds and banks. Thus canoeists or swimmers can all too readily find themselves trespassing, even if they don’t touch land. In Scotland, the Land Reform Act explicitly included access to inland waterways, and even enshrined the right to responsible wild camping anywhere, following the Scandinavian model. We in Wales and England have a long way to go.

The huge success of the 1:25 000 Explorer maps has had an axiomatic consequence in the slump of sales for the 1:50 000 Landranger series. On a sentimental level, this saddens me greatly, for the bright pink maps that have enthralled me for so long are the bedrock of the Ordnance Survey, the direct descendants of its very first map, the One Inch of Kent, over two centuries ago. It is, however, inevitable. Why would anyone buy the three 1:50 000 Landranger maps for a holiday exploring Pembrokeshire, when they could examine the precise same area, at twice the scale and detail, in just two 1:25 000 Explorer OL maps? This strange anomaly is repeated across the whole of Britain: it takes two Landrangers to give you a complete picture of England’s newest national park, the New Forest, but only one generously proportioned Explorer. You want a complete map of the Shetlands? Four sheets at 1:50 000 or five at twice the scale?

Despite their tumbling sales, and despite the fact that only about eighty of the 204 sheets either break even or make a profit, Ordnance Survey makes all the right noises about its commitment to the Landranger series. It promises to keep the entire series intact and updated, as befits the national map agency, even one run these days on largely commercial grounds. The government subsidy that kept the organisation in profit ended in 2006, although OS can now charge the various government departments that rely on it a market rate for data and maps, so it balances out in the end.

I do worry about the 1:50 000 series, though. Commercially, some of the more remote Scottish sheets sell only two or three copies a year—how on earth can that be sustainable in a cut-throat commercial world? As with the Royal Mail, the business and the money is all in the urban centres, but, to qualify as a truly national service, it needs to provide the same standards to the thinly populated, eternally unprofitable bits of the country too. As someone who lives in just such a place, I’ll be watching carefully.

For now, though, the series remains intact and integral, a splendid portrait of our islands that can still keep a map addict quiet for hours in enthusiastic perusal. Much as I love the 1:25 000 Explorer maps, especially when out walking, they haven’t yet captured my heart—and I don’t think they ever will—in quite the same way as the 1:50 000 series. The Explorers’ view of the country is just a bit too close up to afford you the bigger picture, leaving you a little cross-eyed with all that detail. Furthermore, if you wanted to collect the full set of England, Scotland and Wales, you’d need to buy 403 maps, rather than the far more attainable 204 that will give you a complete picture of every British road, railway, track, settlement and farm at a scale of one and a quarter inches to the mile. And although I was a reluctant convert to the idea of having to plaster every map’s front cover with a photograph, the images on the covers of the Landranger series are far more beguiling—‘sculptural’ was the word the OS Product Manager used—than the shots of identikit families grinning in bike helmets that are generally used on the Explorer covers, doubtless to emphasise their invaluableness in fully enjoying the splendours of Leisure Britain™.

Like Britain itself, the 1:50 000 series is often beautiful, sometimes ugly, but always revealing and forever fascinating. It portrays the very best and the very worst of our country with admirable equanimity. Some sheets work better than others, of course, and to illustrate those differences, as well as many of the facets that make this the world’s finest collection of general-purpose maps, I’ve picked out what I consider to be the five best, and five worst, Landranger maps:

THE TOP FIVE 1:50 000 LANDRANGER MAPS

Although they are in undoubted contention for inclusion on this list, I’ve already wittered on enough about my first two 1:50 000 maps, numbers 113 (Grimsby & Cleethorpes) and 189 (Ashford & Romney Marsh), so shall leave them out here. Besides, there are plenty of other very strong candidates, far more than for the list of the worst maps.

123 Llŷn Peninsula

The perfect symmetry of this map, together with the fact that it details one of the most singularly self-sufficient parts of the country, more than compensates for the fact that the bluewash of sea covers twothirds of its surface. The 40 × 40 km square encapsulates the peninsula with pin-point accuracy: the town of Cricieth, traditionally the gateway to Llŷn, is neatly bisected at the map’s eastern edge; the demarcation line between the peninsula and Snowdonia, the main A487, cuts along parallel with the far right of the map.

It is, however, the peninsula’s shape that fits the map so beautifully. The ‘mainland’ (Llŷn feels so much like an island that you do find yourself looking back at the Snowdonia mountains and thinking of them in that way) is connected only at the very top right, north-east of the map; from there, the muscular landmass of Llŷn stretches south-west like an outstretched arm that’s either pointing or straining to grasp. Either way, the object of its focus, or grasp, is the peninsula’s legendary full stop, Ynys Enlli (Bardsey Island), the Welsh Avalon, the shapely island of pilgrimage and sainthood that sits plumb in the map’s bottom-left corner. There’s a sinewy sparseness to this map, a sense of quiet perfection with nothing spare: in the area that became the bulwark and muse of R. S. Thomas, it’s the cartographic equivalent of one of his poems.

131 Boston & Spalding

Had I been drawing up this list for my own consumption only (and it is exactly the kind of thing I would have happily spent a wet afternoon doing thirty years ago), the chances are most of the entries in my Top Five OS Maps would have been of the flat fringes of our country—the Spurn Head and Dungeness sheets that were, after all, the origin of my collection. Strange though it may seem for someone who has chosen to live in the mountains, I find a rare thrill in those blasted landscapes where the line blurs between sea and sky—and they make for uncommonly striking maps.

There’s no flatter map than OS number 131. Uniquely among the 204 sheets of the Landranger collection, it includes not one single contour within its borders: nowhere reaches the modest height even for the preliminary ten-metre line. Well, that’s the case on my original 1980s version of the map; I see that the gorgeous blankness of the sheet has now been sullied by the inclusion on the map’s southern edge of a handful of zero-metre contour lines. As well as ruining the effect, I rather think that’s cheating. This is a map that speaks volumes about our east coast’s eternal battle with the ocean, before the ditches, dykes, canals and reclamation projects formalised the line between sea and land, or at least attempted to, for the sea will always have the last word on that. Ancient Sea Banks are delineated many miles inland, for instance around the village of Moulton Seas End, now more than six miles from the coast. I remember a school history atlas that I spent hours poring over, where I was particularly engaged by the few parts of our coastline that had substantially changed shape over the past two millennia. One of those few was the Wash, that mysterious inlet at the crook of the east coast, and best known as the place where King John lost his crown jewels to the greedy mud. And still the Wash changes. My First Series 1:50 000 version, from the late 1970s, shows an entirely different frill of coastline to the latest Second Series effort. It’s not a place that we’ll ever be able to pin down.

104 Leeds & Bradford

The redrawing of the map of Britain in 1974 for the new 1:50 000 series ironed out many anomalies of the old one-inch system. Crucial to the new series was the realisation that our great cities needed, wherever possible, to be set centre stage on their appropriate map, so that we could, at a glance, get a sense of Manchester, Birmingham, Glasgow, Bristol or Newcastle within the integral context of their suburbs, feeder towns and green belt. All those cities are presented beautifully and make for some of the finest maps in the series.

In the conurbations of Yorkshire’s West Riding, the principal challenge was to present both Leeds and Bradford well, and this map does that exemplarily. The context to understanding the two cities is their place within the tight knot of vertiginous mill towns such as Halifax, Dewsbury and Wakefield, as well as the wild spaces of moor and mountain and the genteel cobbles of Harrogate and Haworth. It’s also a riot of names that could be nowhere else but Yorkshire: villages such as Luddendon Foot, Mytholmroyd, Farsley Beck Bottom, Wibsey, Odsal, Idle, Owlet, Harden, Greetland, Rastrick, Ossett, Soothill, Scarcroft, Wike, Kirkby Overblow, Spofforth, Scriven, Blubberhouses, Stainburn, Birstwith, Thwaites Brow, Cringles, Glusburn and Goose Eye—a list that sounds more like entries in a dictionary of Dickensian ailments. Everything gets a look-in on this well-framed map. There remains an enigma, however. So particular is the terrain of West Yorkshire that proximity on a map often means very little on the ground, as towns can be isolated from each other by steep hills, strange road systems and a proudly singular history. To the untrained eye, the southern half of this map might look like an almost continuous urban rash, but that’s only a fraction of the story. Like the Valleys of south Wales or the Black Country to the west of Birmingham, the area looks like a city, but is, in truth, a conglomeration of very different towns and villages, and woe betide anyone who gets them mixed up.

196 The Solent

As you’d hope from the sheet that covers Ordnance Survey’s own headquarters, this is a wonderful map: a tight frame of staggering variety and much beauty. Within the same sheet, there’s the heath and woods of the New Forest, the full might of two great cities, a frantic network of motorways and dual carriageways, buxom estuaries and, capping it all, the entire Isle of Wight. It’s the island that really does it, with its beguiling shape so perfectly touching the sides; the jagged chalk outcrops of the Needles demanding a little expansion at the left margin that only emphasises their stature. Islands that so snugly fit their OS maps are always highly satisfying—such as sheets 95 (Isle of Man), 60 (Islay), 6 (Orkney—Mainland) and 114 (Anglesey / Ynys Môn)—and so it is with the Isle of Wight. It’s often described as lozenge-shaped, though, to my mind, the island looks more like a crusty old pie, probably a good old-fashioned steak and kidney, which is what I also imagine it would taste like.

They say that visiting the Isle of Wight is like going back to the 1950s, and there’s a slight feel of that even on the map: the physical look of very different decades gazing at each other across the Solent. The island contains all of one mile of dual carriageway: beyond that it’s mainly B roads, country lanes, villages, farms, harbours, downs and chines. On the mainland, by contrast, it’s all very now, the numerous marinas and jetties snaking up the estuaries, the sly marketing (Hamble village, after acting as the set of the yachtie TV soap Howard’s Way, is rechristened on the new map as the estate agent’s far dreamier Hamble-le-Rice), the vast oil refineries, the growing guts of bitter rivals Southampton and Portsmouth.

Modern (i.e. Landranger Second Series) versions of this map also contain rare and intriguing examples of an Ordnance Survey joke. When, in the 1950s, a bored draughtsman drew some cartoon boats on the Manchester Ship Canal, he inadvertently left one on the map as it went to press. Months later, a phone call from a startled architect alerted OS to the alien presence and the maps were consequently pulped. Slipping in little visual jokes or coded messages is the challenge to any creatively minded draughtsman, and here someone has managed it—three times. Look very closely (a magnifying glass is best) at the cliffs on the Isle of Wight’s south side, immediately east of the Needles. The symbol for cliffs, a rather random downward hatching, is one of the least precise on the OS and thus possibly the easiest to slide something hidden into. Just below the label ‘Warren Farm’ is what looks like REV (possibly KEV), and a mile further east, below the label ‘Tennyson Down’, we see the word BIRSE. Who or what Rev, or Kev, Birse was, we don’t know. It’s a lot better hidden than Bill’s effort; his name can be seen as clear as day in the cliffs a mile north-west of the island’s southernmost point, just above the label ‘Blackgang’. (Type SZ485766 into the Get-a-map facility on the OS website and scale down to the 1:50 000 map.)

34 Fort Augustus, Glen Roy & Glen Moriston

Among the dozen or so Landranger maps that portray the deep interior of the Scottish Highlands, there are many candidates for excellence. It’s the breathtaking emptiness that impresses most, the sheer lack of anything very much save for mile upon mile of moor, forest, river and mountain. And what mountains they are: the contours are piled up in the dizziest formations, soaring in all directions, occasionally giving way to sheer cliff faces and plunging scree slopes. The emptiest of the lot is probably number 20, a map with so few settlements on it that there was nothing to name it after save for a mountain and a lake, Beinn Dearg & Loch Broom. My choice, however, combines nearly this level of emptiness with a portrait of the most thumping geological feature in Britain, the Great Glen, that fracture in the planet that rips through not just the geography of Scotland, but its entire history too.

This map frames the Great Glen flawlessly. The fault line begins, as the infamous Loch Ness, in the north-eastern, top-right corner, descending directly south-westwards, through Loch Oich and Loch Lochy (were they running out of names by then?), before vanishing in the bottom left of the sheet, having split it with precision symmetry. Threading between the lochs are rivers, the Caledonian Canal, the trackbed of a very short-lived railway and General Wade’s Military Road, constructed as part of the well-mapped clampdown on the Highland clans in the mid eighteenth century. There’s a strange incongruity in the Highlands, in evidence on this map, between the sublime natural landscape and the suppression and brutality that it witnessed. Even if you only consider the aesthetic splendour of the landscape, the lochs and mountains in particular, it’s galling that so much of the attention hereabouts is soaked up by the existence or not of the Loch Ness Monster, for the loch itself is staggering enough with no help needed from all the hype surrounding it. Loch Ness contains 263,162,000,000 cubic feet of fresh water, more than the combined total of every single freshwater lake in England and Wales. As can be seen from the isobaths, or underwater contours, on the map, the loch is over 750 feet deep, enough to engulf the fifty-storey One Canada Square tower at Canary Wharf, leaving just the top seventeen feet of its pyramid poking out above the water. This is a land of physical superlatives, consummately encapsulated in this fascinating map.

AND THE BOTTOM FIVE

Even the Ordnance Survey don’t always get it quite right. Here are some of the 1:50 000 Landranger maps that just don’t work very well.

11 Thurso & Dunbeath

Truly, a crap map. This has to be the most pointless of all the 204 Landranger sheets; it’s no surprise that it is right at the bottom of the list of sales, for there is no real reason to buy it unless you’re an OS obsessive who simply has to have the full set, or one of the residents of Lybster (population 530), Latheron (51), Latheronwheel (201) or Reay (296), for these are the only villages unique to this map. Every Landranger covers 1,600 sq km, and many have inevitable overlaps with neighbouring sheets. On map number 11, however, 1,208 sq km, over three-quarters of the map’s surface area, is replicated on other OS sheets, most notably number 12 which is more or less the same map, just with its coverage area shifted a few miles north-westwards. Only 392 sq km is particular to map number 11—and a fair bit of that is sea.

So why does this map, rather than the near-duplicate number 12 (Thurso & Wick: even half the title is repeated), deserve the accolade of the worst OS? Well, this is the far north of mainland Scotland, remember, as declared by the inclusion in its title of mainland Britain’s most northerly town, Thurso (which Victoria Wood, in a television travelogue, memorably described as ‘sounding like something you’d rinse your curtains in’). What of the phenomenal coast? The seabird-swirling Dunnet Head, Britain’s most northerly point? The world-famous John O’Groats? The Highland mountains? That’s the problem—the map has none of these. This is Caithness, a turgid flatland of wet moor and angular forestry plantations; there are no mountains to speak of. Worse, the map slices through the upper limits of Thurso town and doesn’t quite make it up far enough to include any of the spectacular northernmost coast. All of the interesting bits are on map number 12.

176 West London / 177 East London

While, in many ways, the two 1:50 000 maps that cover the capital are hugely impressive, especially when placed and pasted together on a wall, there’s something not entirely satisfactory about London at this scale. It looks good as a purely aesthetic rendition of a huge, sprawling city, but you’d never use a Landranger map to navigate through the streets of London, and if you did, even the finest map-reader would go wrong somewhere. There’s just too much crammed into too little a space, rendering invisible all of the things that make the city such an exciting place. The Underground system, for instance, which makes unpredictable appearances only when it emerges into daylight, mostly at the city’s fringes, seems to come out of thin air. So, while the great tube stations of the West End and City remain entirely unseen, every last Legoland halt on the Docklands Light Railway is painstakingly delineated, and, to make matters much worse, in the OS’s garish new scheme of light-railway stations as yellow discs instead of the customary red. It looks awful, none more so than in areas of the East End with a glut of outdoor stations, overground and DLR. The tangle of black lines, together with the seemingly random blobs of yellow and red, look like some strange shrub that’s sprouting poisonous berries.

We shouldn’t expect a 1:50 000 map of London to be able to cope with all the demands potentially laid upon it, of course. We shouldn’t expect it to show the tube stations, the passageways, the arcades, the tiny parks within squares or every building of significance, because it can’t. And that’s where these maps become nearly redundant, for it is those features that make London so magical, not the Westway or the North and South Circulars, all massively mapped here. Landranger London looks choked to death, an impenetrable block of no potential and no great interest. It’s not as bad, however, as the picture of London on the 1:250 000 Travel Map. Thanks to the slavish adherence of OS to the blandishments of the tourism industry over all else, central London is obliterated by an illegible splurge of symbols for museums, churches, historic houses and a welter of those blue stars that can mean anything from a standing stone to a puppet theatre. It is utterly unusable; the scale is way too small to locate things with any accuracy, the ‘attractions’ aren’t identified and the whole sorry mess tells you nothing more than that there are lots of things to see and do in central London. Who’d have thought it? The 1:50 000 Landrangers are not quite that bad, but the 1:25 000 Explorers are much better, and, it’s got to be said, the A-Z better still. That is London’s natural map.

148 Presteigne & Hay-on-Wye

How could I even appear to pick on such an idyllic stretch of Welsh-English borderland as this? I adore both Presteigne, the handsome old county town of Radnorshire, and Hay-on-Wye, the eccentric—if a little too self-consciously so—second-hand-bookshop capital of the world. As a ten-year-old, I was thrilled by the hoo-ha that attended ‘King’ Richard Booth’s unilateral declaration of Hay’s independence—complete with its own passports, border posts and stamps—on April Fool’s Day 1977. These days, such pronouncements are two-a-penny—Lonely Planet has even published a guidebook to the world’s soi-disant micro-nations—but this was the first I’d been aware of, and it enthralled me. Twenty-seven years later, I interviewed King Richard for my Great Welsh Roads TV series, and, although much diminished by a stroke, he was still a towering and hugely entertaining figure.

Between and around these two titular border towns are some of the most appealing villages and unhurried countryside you could find anywhere. So what is wrong with the map of such a blessed part of the world? It’s a bit of a repeat of the Thurso situation, really, if not on such a dreary scale. Because Britain has the bad manners not to be exactly wide enough at this point to accommodate a neat row of Ordnance Surveys with little overlap, it’s all got rather banked up and squashed here. Five other sheets overlap number 148, leaving only 395 sq km out of a possible 1,600 as unique to this one map—only a sneeze over the total of the unfortunate sheet number 11. When I was building up my collection as a youngster, I waited ages before bothering to get this map, despite the fact that it bordered the area where I lived; I just wasn’t getting enough that was original for my pocket money (this was before the epiphany dawned that they could be had so easily for free). Both titular towns, Presteigne and Hay-on-Wye, make cameo appearances on neighbouring maps, though that’s nothing compared with the plight of the Herefordshire villages of Orleton, Yarpole, Luston and Eyton, to the immediate north of Leominster. They sit in a 5 × 8 km rectangle that can be found on this map, and three others. The residents of this little slice of gastro-pub England are the most over-represented on Landranger maps of any in Britain; it would cost them the best part of thirty quid just to collect the sheets that they appear on. A wonderful area, but a bit of a rubbish map.

110 Sheffield & Huddersfield / 111 Sheffield & Doncaster

On the back cover of any pre-millennium Landranger, take a look at their index map of Britain. To help you find the right sheet for your purpose, numerous towns and cities are marked, from LONDON (the only capitalised example), through most of the large and mediumsized conurbations and down to some surprisingly obscure choices: Helmsdale, Kingussie, Girvan, Moffat and Tongue in Scotland; Dolgellau, Pwllheli, Bala and Fishguard in Wales; and, in England, Bude, Ilfracombe, Ripon, Workington and Blyth. For the first decade of the Landranger series, Aysgarth (population 197) in the Yorkshire Dales was deemed sufficiently important to be marked on the national map, but not on the cover plan of its own sheet, number 98, Wensleydale & Wharfdale. There’s Hereford and Gloucester, but no Worcester; Leicester and Birmingham, but not Coventry; Cambridge but not Peterborough; Southampton but not Portsmouth; Whitby but not Scarborough; and no Stoke-on-Trent, Cheltenham, Ipswich, Bath, Milton Keynes, Canterbury, Bournemouth, Reading, Newport, Bradford or Darlington. Most bizarrely of all on the index map, there’s Doncaster, but no Sheffield.

That the fifth-largest city in England failed to appear on the national map gives a small hint that what worked so well in West Yorkshire, on the Leeds & Bradford sheet, has gone a little awry in what used to be called the People’s Republic of South Yorkshire. Unlike any other major British city, Sheffield is tucked in so close to the margin that it has to appear twice, on overlapping sheets, and then spirited away at the very bottom. To get any decent idea of Sheffield’s hinterland, you’d need to buy four maps. What has OS got against poor old Steel City that it snubbed it twice?

46 Coll & Tiree

It’s a fairly close contest for the title of Landranger map that shows the least amount of dry land, but this is the winner, and for that reason alone, it deserves to go in the list. Map number 46 covers the two islands of Coll and Tiree, to the west of Mull (also quite badly served by the 1:50 000 series, needing three rather clumsily divided sheets to show its 338 square miles; the island of Anglesey, by contrast, at 276 square miles, needs just the one). The two islands, with the scattering of uninhabited skerries known as the Treshnish Isles, account for about 9 per cent of the map’s total surface area, leaving a whopping 91 per cent as featureless pale blue sea. And featureless it surely is: had Ordnance Survey continued with its plan to map isobaths of the sea, so that we could tell at a glance the comparative depths around our shores, the map would have been far more interesting. The blank bluewash of sea, especially on a map like this, where it is so much the dominant feature, is one of the Landranger series’ least endearing features. Many of the Scottish lochs have isobaths mapped, and the old One Inch series showed them in the sea at five and ten fathoms, but it was decided to do away with those for the new series as they were seen to encourage amateur sailors to recklessness. The result makes the sea look bland and uniform, with no hint as to its thrills and dangers. This was something that a company like Bartholomew mapped so very much better; its seas a gradually darkening series of blues according to the water’s depth. It wasn’t a massive difference, but it was enough to allude to the mysteries below.