The town of Baarle, splintered between Belgium and the Netherlands

4. BORDERLINE OBSESSION

I have always loved the moments of travel when, brought to a halt by a striped barrier, approached by unfamiliar uniforms, you feel yourself on the brink of somewhere unknown and possibly perilous.

˜ Jan Morris, Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere

Where there’s a map, there’s a border. Often, it’s the boundaries—political, topographical, cultural, linguistic, historical—that are a map’s raison d’être: a show of muscle, a graphic illustration of change or simply a bold, bright statement of territorial integrity. And how they fascinate us: a map addict adores his borders, knows them intimately, and craves to visit them and the places that straddle these hallucinogenic divides.

Borders may begin as lines on the map, but all too soon they deepen into cultural and even physical reality, to the extent that they can sometimes be seen from space. Look on any website showing satellite imagery of the globe, and you can often see how a border on the map can be clearly delineated in the landscape, as neighbouring countries prioritise different uses for the land and alternative agricultural practices. The starkest example is between the American states of Montana and North Dakota on the one side, and the Canadian state of Saskatchewan on the other, but, merely from the aerial evidence, you could also plot the international borders between Russia and Finland, around the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad, and between Namibia and Angola. You can pretty much trace the entire outline of Kuwait without any labels needed. Borders are very real.

Britain is a land that takes its borders very seriously indeed: its constituent countries, their counties, regions, districts, ridings, hundreds, palatines, commotes, wapentakes, liberties, rapes, cities, towns, boroughs, constituencies, wards, dioceses, deaneries, archdeaconries, parishes, even postcode districts—all can inspire fierce loyalty and raise passions among map aficionados. And although there’s nothing particular to see, save for the occasional signpost or flag, perhaps a subtle change in tarmac, we love also to visit these borders, to see and feel them, jump across them and back again, to linger on the edge of two, or more, places at the very same time. It appeals to two contradictory sides of our character in the very same moment: the urge for order and neatness, together with our need, occasionally, to hang in limbo.

Of course, the Americans do it bigger and better: they’ve managed to create an entire national park and a major tourist attraction, pulling in half a million visitors every year, out of nothing more than a remote spot in the desert, which just happens to be where the states of Utah, Arizona, Colorado and New Mexico all meet at right angles. Four Corners, as it’s known, has a car park the size of Wiltshire, an interpretive centre, restaurants and gift shops galore, as well as an almost permanent queue of people waiting to climb the monument where the exact borders meet and photograph their loved ones straddling the four states. The most popular pose is like something out of the game of Twister, each foot and hand in a different state and a daffy grin to prove it. It’s easy to scoff, but I know full well that if I’d been growing up within two days’ travel of the place, I’d have made my dad’s life hell until he finally took me there.

It’s the odd and anomalous boundaries that we love the most, and there’s a steady stream of us touring them for no other reason than that they exist on our well-thumbed maps. Take Europe’s wonkiest border, which can be found in one of its straightest corners, the wealthy farming flatlands straddling Belgium and the Netherlands. This was a place that I was bursting to see ever since becoming aware of its existence. The small town of Baarle bestrides both countries, despite being five kilometres on the Dutch side of the border. Within and around the town, there are twenty-one separate exclaves of Belgium, which, in turn, contain nine further enclaves of Holland: the smallest of these thirty angular parcels of land being half a field, not quite twothirds of an acre. It’s a situation that’s been nearly a thousand years in the making, from a succession of medieval and modern treaties, agreements, land-swaps, sales and stand-offs between the Lords of Breda and the Dukes of Brabant. Just walking through Baarle’s neat streets means that you will cross and re-cross the border numerous times, and the authorities have kindly assisted the visitor by marking these frontiers in the pavements with lines of + + + + + markings, painted either side with B or NL accordingly (there’s going to be some almighty tarmac inconvenience when Belgium finally disintegrates).

Baarle’s mad borders are its single biggest asset: without them, the place would be a slumbering country town unnoticed by practically anyone. It’s a regular photo opportunity for Dutch and Belgian royalty or politicians to announce mutual accords in the town (the Enclave Room, through which the border runs, in Den Engel Hotel is the usual backdrop). Tourists flock to Baarle, to emulate the same pose as their masters with a foot either side of the divide. The + + + + + frontier symbol, scored in so many pavements, repeats itself ad nauseam on posters, shop signs, logos, town literature and almost all of the postcards available. Baarle is a border-collector’s wet dream.

Officially, it’s not one town, but two: Baarle-Hertog (Belgium) and Baarle-Nassau (the Netherlands), and there’s double everything. Two town halls, two burgomasters, two fire departments, two national phone companies with boxes side by side, two websites for anything (.be and .nl), two languages (Flemish and Dutch), two police chiefs both sat in the same building with their respective flags at the front of their desks. Houses identify which side of the line they’re on by their number plaques—rectangular red, white and blue for Dutch, oval black, gold and red for Belgium—although, of course, some houses have their front door in one country, their back door in the other. Some houses have in the past even moved their front doors to change nationality and take advantage of better fiscal arrangements on the other side. Even graves in the cemetery are marked with little metal flags to identify which side of the line the deceased hailed from.

In some other parts of Europe, a situation like this could be horribly explosive, but in this plump, placid arable landscape, it’s all accepted with a shrug, a wry smile and a weather eye on the tourist coaches packing the town’s car park. Not that the divide is merely academic: the ‘problem’ of Baarle has occupied huge amounts of governmental concern over the centuries; spats and smuggling were commonplace, while the impasse in divvying up some of the local agricultural land has resulted in some wonderfully uncultivated, and ecologically rich, terrain in an area otherwise sprayed and cropped to within an inch of its existence. These days, the effect is most commonly seen in retailing, for Baarle’s shops certainly seem to have settled into their appropriate national sectors. In the Belgian parts of the town centre, it’s all chocolate emporia, chip shops and tobacconists urging Dutch strollers to stock up on cheaper Belgian fags. Just up the street in the Netherlands, it’s mainly banks, home-interiors shops doing dull things in pine and—proof indeed that you’re in Holland—an erotic bazaar (which, like most Dutch shops, looks as if it’s run by the council), its earnest window display of lubricants and mannequins in nasty nighties enough to bore anyone off sex for life.

For the map addict and border-spotter, Baarle’s pièce de résistance is the interactive 3D model, or maquette, of the town centre, housed in an octagonal glass house just inside a Belgian enclave. There the town lies in perfect miniature until you press a button and the two countries separate horizontally, the Belgian bits rising up an inch or two over their Dutch neighbours. Or so I thought at first, before realising that Belgium stayed still, while the Dutch parts sank, which, considering Holland’s eternal battle with nature, seemed hellish tactless. A hint perhaps that, behind the postcards and we’re-all-Europeans-now camaraderie, there was some deadly serious national one-upmanship going on in sleepy Baarle.

If you took a straw poll of the tourists ambling contentedly around Baarle, you’d likely find that a fair number of them had gone out of their way to visit some of the other weird borders snaking around our continent. The chances are, every one of these tourists has been a map aficionado from a very early age, for that is where this strange interest is incubated. It starts with noticing the little nodules of enclaves, exclaves and tiny countries or counties in the family atlas. It progresses through hunting out larger-scale maps to get a closer look and digging out weighty reference volumes in the local library to find out a little more about them. Before long, you’re harassing your poor parents to take you to see these far-flung places: anything from a lengthy diversion on some Sunday outing in order to take a look at Flintshire (Detached), to trying to persuade them that the family holiday this year really should be in northern Italy, because then you can bag San Marino (and, at quite a push, perhaps the Vatican City and/or Monaco).

That’s really all it’s about: bagging them. Just as climbers in the Highlands brag about bagging their Munros, we map addicts collect countries, counties, enclaves and exclaves, storing them up in our heads with guarded jealousy. We will—and do—go hundreds of miles out of our way to add a Luxembourg or a Liechtenstein to the list. We might only be there for a matter of hours, but that’s not important. We’ve been, it’s been seen, it’s ticked off. All too often, though, these are not places to linger. After all, somewhere whose principal attraction is its odd borders isn’t necessarily going to provide much else in the way of entertainment, once you’ve sent a few postcards (‘Look where we are!’) and admired the profusion of brass plaques for dodgy banks making the most of the local feudalism and tax-free status. More often than not, tiny countries are a crushing disappointment. I remember cajoling a companion on my first InterRail holiday, at the age of twenty, into a lengthy detour to visit Andorra. As well as its obvious appeal as one of the continent’s micro-states, I was hopeful that it might prove to be something of a European Tibet, a mountain kingdom far from the pressures of our grubby lives, a repository of the highest spiritual and cultural order. We sat on a bus that zigzagged its way at the speed of a glacier up into the Pyrenees, only to find that the country was a hideous duty-free shopping mall, five thousand feet above sea level, swarming with crazed people ramming their car boots full of cameras, fur coats and bottles of Pernod. All there was to do was get pissed on cheap cocktails and feel faintly conned and very sick on the bus back down the hairpin bends.

Collecting mini-countries is how a border-spotter’s dependency begins, but you’re soon on to the hard stuff with me and all the others in Baarle: the enclaves, exclaves and other freakish anomalies of the European map. The internet has taken the sport to unheard-of levels: virtually everyone sweating their way up the 5,368-foot peak of Sorgschrofen Mountain in the Alps is only doing it so they can photograph themselves at the rock on the summit that marks the point where the borders of Germany and Austria cross each other, creating the exclave around the village of Jungholz. These days, they then post their photos straight on the web. There are whole websites dedicated to pictures of smiling young men—who you know probably still live at home with their mums—grinning at different signposts marking these cartographic exceptions to the rule.

Such hangovers from medieval treaties and inbred parochialism are much more than mere diversionary footnotes to geography, however, and not all are as cheerily twee or geared towards tourism, gambling or shopping as Baarle, Jungholz, the Spanish exclave of Llivia in France, and German Büsingen or Campione d’Italia in Switzerland. Enclaves and exclaves have played, and continue to play, a hugely disproportionate role in world affairs, often proving to be either the impossible-to-shift grit of some ancient dispute or the spark that ignites a new one. Some of the most famous—Danzig, Kaliningrad, Berlin, Dubrovnik, the Gaza Strip, Nagorno-Karabakh, Chechnya, Ossetia, Gibraltar, Ceuta and Mililla—are bywords for stand-offs, wars and misery stretching back centuries. You’d think that progress and globalisation were quietly ironing out these aberrations on the map, but quite the opposite is true. Many more new enclaves and exclaves were created in the late twentieth century than were disposed of: the break-ups of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia alone unmasked twenty brand new ones in Europe and western Asia, some desperately fractious.

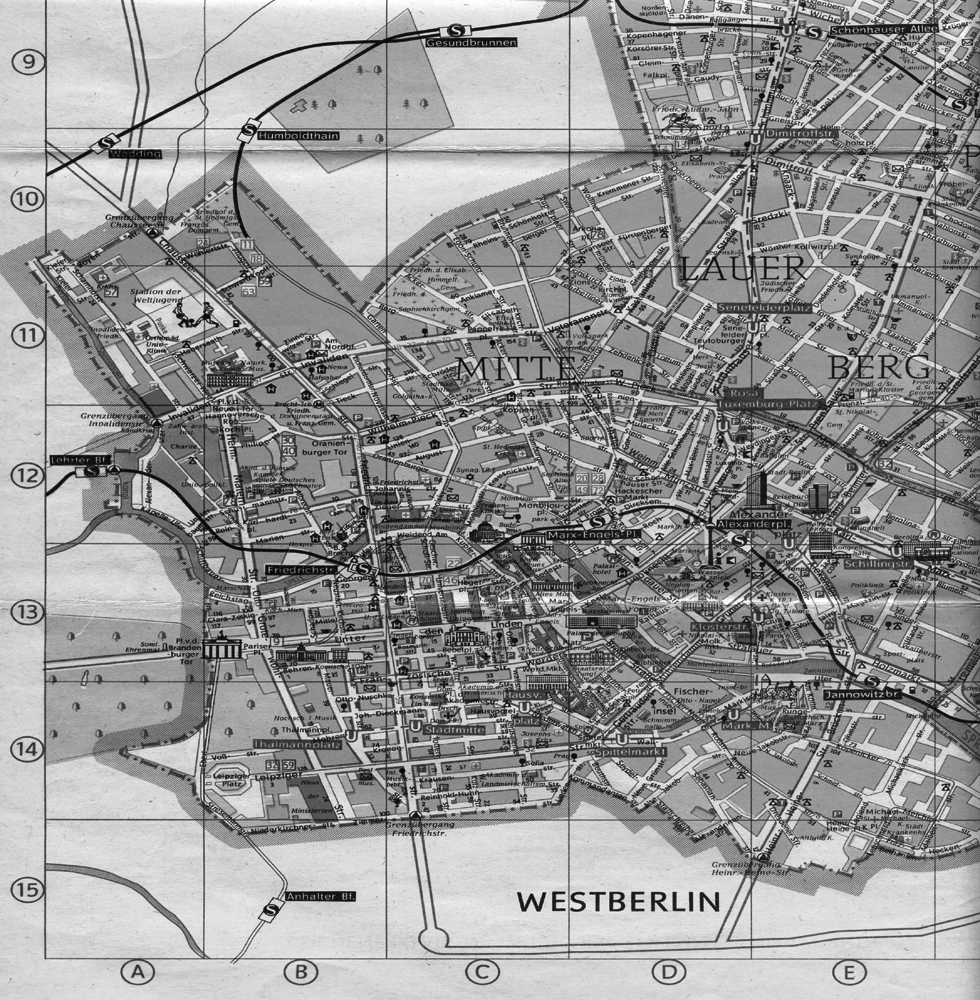

Some have been ironed out, yet their ghosts refuse to budge. There is no modern border quite as infamous as the Berlin Wall, despite dividing the city between the Soviet and western sectors for only forty years, the physical wall a mere twenty-eight. Its destruction in November 1989 was the single most graphic and joyous proof that this divided city, its divided country and its divided continent, could finally be reunited. Only tiny stretches of the Wall remain today, yet its influence plods doggedly on. No Berlin street map is complete without a line marked ‘Course of Wall’ running across it. Maps, aerial photos, postcards and posters showing the Wall in aggressive situ outsell all others; lumps of masonry of dubious provenance are still the most popular city souvenirs of the city; the few remaining kilometres of graffitied concrete are photographed thousands of times daily; museums about the Wall and the city’s brief divide draw in coachloads. Districts that were once in the eastern sector still underperform against those in the west, and everyone still uses the division to state where they live, work and play, or where they are going. As the vicious reality of partition recedes further into history, its iconic status only grows. We are absolutely fascinated by it, and becoming ever more so.

The first time I went to Berlin, I was obsessed with scouring the city for the scars of the Wall, and on finding them, feeling some kind of strange rush before hurtling off to look for the next. Back home, I lost days gazing at maps, photos and YouTube videos of the city, before, during and after its divide. Best was the progression of historic tube maps, showing the system growing, splitting, contracting, reuniting and finally growing again, plus the shaky home movies of the Geisterbahnhöfe (ghost stations), the U-Bahn and S-Bahn stops in the eastern sector that lay on lines connecting different parts of the western zone. These used to be sealed, while armed Ossi guards loitered on dimly lit platforms to make sure that no one got on or off as the train ambled through. Some stations straddled the border, so that platforms and exits had to be divided or sealed accordingly. In a few places, there were parallel railway lines belonging to the two different halves, necessitating huge fences between them, lest anyone tried leaping from a train or peering too hard at their unknown neighbours.

An East German map of Berlin from the days of the Cold War

Because these Geisterbahnhöfe were sealed so suddenly in 1961, they were perfect time capsules when they came to be reopened in 1989 and beyond. The tourist industry and the nostalgia freaks are gnashing their teeth that at least one wasn’t preserved that way: although signage in Hitler’s 1930s Gothic typescript has survived in many of them, the main motivation in 1989 was to erase the city’s hideous division, not to slap on a heritage order and glorify it. The same happened at the legendary Checkpoint Charlie, which was swiftly demolished on the Wall’s demise. A naff replica has now been rebuilt for the tourists to pose at. Our fascination with this short-lived border is not going to go away, and it is not going to help Berliners overcome what they call their Mauer im Kopf, the ‘wall in the head’, for that is as defined and almost insurmountable as the physical original.

Everyone’s mental landscape consists of Mauern im Kopf: those decreed from on high and woven into our personal history, as well as those drawn on no map at all, a place or a moment where we leave the familiar or comfortable and enter the unknown. Our towns, villages, fields and cities are full of such invisible borders—places we just don’t go, that are on the other side. My partner grew up precisely three and half miles, as the crow flies, from where we now live. Until he started seeing me, at the age of twenty-nine, he’d never once been to this village. It lies across the other side of a divide that’s drawn on no map, but is as real yet invisible to the casual eye as a country-house ha-ha. In Wales, such divisions are manifold: the concept of one’s milltir sgwar—square mile—is deeply ingrained in the culture, so that attitudes, physical appearances, even specific words in the Welsh language change from village to village, valley to valley.

It’s far from just a Welsh thing, however. At the age of six, living on a modern housing estate in suburban England, my mental map of it was crystal clear. One street in particular was a no-go area; I felt supremely daring even taking my bicycle up it, and would execute a swift U-turn out at the first sign of a twitching curtain or returning car, my heart pounding. There was no specific threat or bad memory connected to it; it just didn’t feel like territory I could be familiar with. As my bike shed its stabilisers and began to take me further into the town and the surrounding countryside, there were numerous places that were crossed off my mental map as being out of bounds: streets, roads, lanes, closes and even leafy avenues where I’d never go. My dad once bought me a street map of our home town, and I remember staring at the parts that frightened me or left me cold, learning the names of the ‘enemy’, prepared only to get to know them vicariously from the map. Sometimes this was because of singular dangers: a grumpy old man who’d once shouted at or tried to grope me, a family that scared me, a building that spooked me (there were plenty of those), the home of someone that terrified me at school (ditto). Often, they were for no good reason at all, just a vague sense of unease which I couldn’t understand and didn’t want to go any deeper into. Frequently, these no man’s lands necessitated considerable detours, but I was always happier to do that than face these often invisible demons gurning out of the map at me. To some extent, I still feel that today: there are roads I positively dread having to take, so soaked do they seem in some unspecific melancholy or foreboding.

Borders of the mind, unmapped and mostly unseen, are the ones that most affect our lives on a day-to-day basis. The shops we go to, the streets we walk down, the parks and towns and stations and riverbanks we use, all dictated by a sense of there being a line over which we do not like to cross. Gang warfare has always depended on such identification with place: the divide between where you can and cannot go is sometimes literally a matter of life and death. Such brutality is not only confined to such obvious culprits as drug-dealers or racketeers: six people died in Glasgow in 1984 because of a turf war between icecream vans.

If you hail from this corner of the world, it would seem that there’s barely room for many imaginary boundaries, for the swiftest of glances at the globe will show that no continent does actual borders quite like the Europeans. Many national or sub-national boundaries in the Americas, Africa and Australasia follow natural features and, where they’re a bit thin on the ground, it was out with the ruler and a steady line along some parallel or other, often for hundreds, even thousands of miles—the cause of many a subsequent problem, it must be said. In Europe, millennia of scrapping over every last inch of turf has produced borders that wriggle and squirm across the map like a nest of vipers. For those of us in Britain, where the principal borders—between England, Wales and Scotland—have remained substantially the same for well over a thousand years, what is most amazing about those on the European mainland is how fluid they seem. Compare maps of 1750, 1850, 1950 and today, and very little seems to have stayed the same. Some change on a bewilderingly regular basis; if someone born in 1870 had lived into their late seventies in the same Strasbourg house, they would have changed nationality five times, being bounced like a ball between France and Germany.

To sample the borders of Europe, I recently went InterRailing again, this time with my partner and thankful indeed to have already ticked Andorra off my list. The trip took us from Paris to Corfu. Direct, it’s just a shade over a thousand miles, although our journey more or less doubled that, crossing fifteen international borders in the process. These were marked with varying degrees of boot-stomping and passport-stamping. Some—France into Belgium, into Holland, into Germany; the Czech Republic into Slovakia—passed by unnoticed, the change in country marked by little more than a change in signage on the station platform. Some involved long waits at dusty frontier halts, a couple of platforms and a customs shack in the middle of a field. Claques of uniformed officials banged up and down the train, shouting ‘Pass!’ at anything that moved. Finally, the train would shudder its way out of the station, before creaking to a halt twenty minutes later at the frontier station on the other side of the border, where we’d go through the whole process again.

By far the most intimidating crossings were of borders that weren’t even there two decades ago, namely between the member states of the former Yugoslavia; each involved unyielding stares, lengthy scrutiny, a few staccato questions, lots of muttering between armed officials, and finally a large stamp being flourished to ink the pages of Her Britannic Majesty’s passport. As each new state has peeled off the rump of the old country, it seems that their greatest growth industry has been in scores of uniformed officials to police their shiny new borders. As ever, the people attracted to such a career (job description: glaring, mumbling, making people feel very uncomfortable, possessing the ability to wear big boots and silly hats with no shame or sense of irony whatsoever) are the kind that you know had sand, soil and shit kicked in their faces throughout their childhood, but who have been getting their revenge in regulation nylon slacks ever since. Crossing twice into Serbia was especially cheerless, for, although border guards anywhere look like serial killers in the making, the chances are that here they actually were hurling their neighbours into shallow graves just a few short years ago, and would relish the chance to redeploy such skills on smart-arse Western tourists, especially those scribbling it all down in a notebook.

Using the ex-Yugoslav railway network was a ghostly experience, for it reeked of the painful recent past. Stations that, not so long ago, were bustling with activity to destinations far and exotic, have been reduced to spectral affairs, one or two trains a day going any distance at clodhopping speed (the tracks are in a terrible state of repair), plus the odd local rumble through the suburbs. The station at Skopje, Macedonia’s magnificently mountain-ringed capital, was the most sombre. A huge earthquake in 1963 levelled the city and a new elevated central station was built as part of Tito’s plan to create a socialist architectural Utopia on the plain of the Vardar River. The ten-track station under a giant tubular roof once hummed with the chatter of those whisking away to Athens, Salonica, Pristina, Belgrade, Sofia, Istanbul, Zagreb, Ljubljana, Vienna and all points between. Now, everything stood semi-derelict and forlorn, the destination-indicator board had flicked its last long ago, the cafés and waiting rooms stayed locked, the platforms deserted. The only flurry of life came when the occasional train dragged slowly in: briefly the station flickered and crackled, before collapsing back into torpor.

Ironically, the happiest border crossing of all was the one that we’d been most nervous of and was logistically the most difficult to organise, namely crossing from Montenegro into Albania. Montenegro’s dusty capital, Podgorica (né Titograd), is only fifteen miles from the border. There’s a railway line to Shkodër, northern Albania’s biggest town, but no trains currently use it. There are no buses, either, so the only way to do it was to find a taxi that would take us to the frontier, walk through it and hope that there would be someone on the other side to take us further. We asked at our Podgorica hotel about finding a taxi. The young girl on reception, who had been a great laugh and a rich mine of information up to this point, stared incredulously. ‘Why you want to go to Albania?’ she barked. ‘You are drug smugglers, yes? Spies? Trafficking of people?’ ‘Er, no,’ we protested weakly. ‘Just we’re so near, and it would be a shame not to see the place.’ This didn’t wash at all. ‘I hate Albanians with all of my heart,’ she spat. We’d heard much the same from almost everyone we’d met in Macedonia and Serbia too.

Consequently, it was with some apprehension that we lugged our rucksacks to the border post, having been dropped there by a Montenegrin taxi driver who couldn’t wait to get away. Sat in his little booth on the Albanian side was what looked like a regulation border guard, not much more than five feet tall and with a fussy little moustache. I groaned at the sight. He eyed us warily, before taking our passports from us and studying them very carefully. On reading the words UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN AND NORTHERN IRELAND on the cover, he broke into a huge grin. ‘Ah, Anglia!’ he chuckled. He stood up. ‘Anglia! Meester Bean, Norman Wisdom, Tony Blair!’ Fancy coming from a country known only for three gurning comedians. I did a weak Norman Wisdom impression, which had him in fits of laughter and calling over his colleague to meet us. As we stumbled our first few steps into what used to be called ‘Europe’s last Stalinist state’ (and where, by a miracle of raw capitalism, a taxi instantly appeared to hurry us on our way), the wheezing giggles of the two loveliest border guards in existence echoed behind us. It was a very accurate omen. There were many more laughs to be had in Albania than in painfully self-conscious little Montenegro, uptight Serbia or anywhere else we’d found in the Balkans.

Because of the suited-and-booted brigade at every border in Eastern Europe, it was impossible not to be minutely aware of the divides between countries, as they stood on the map of 2008. Only twenty years ago, the picture would have been very different, and it could well be again twenty years hence. For the map of Europe with which I was travelling told only a fraction of the story. There were a whole host of ghost nations and their borders stalking us as well. In the current configuration, we went through Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia, Macedonia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania. We also travelled, in a parallel age—it may be past or future; perhaps both—through Wallonia, Flanders, Brabant, Westphalia, Saxony, Prussia, Bohemia, Moravia, Ruthenia, Transylvania, Wallachia, Rumelia, Dacia, Thracia, Dalmatia and Illyria. It sounded more like a wander through the Notting Hill Book of Baby Names.

If the borders of the countries of mainland Europe are in a state of almost perpetual flux, so it seems are some rather nearer to home, those of the British counties. For the most part, these have changed little for seven or eight centuries, until the end of the Second World War, that is. Since then, however, it’s been an almost constant round of reviews, commissions, recommendations, enquiries, submissions, task forces, changes, counter-changes and a bewildering quantity of Acts of Parliament. And we’re still not happy with the result. Far from it; there’s almost no subject guaranteed to light up the letters pages of local newspapers and online forums quite as spectacularly as the question of county boundaries and county loyalties.

Just like the greater map of Europe, the old county map of Britain contained a stack of anomalies and historical quirks. It had its Luxembourgs in the shape of Clackmannanshire, Rutland, Radnorshire, Kinross-shire and the Soke of Peterborough; its Danzigs and Dubrovniks in the clutter of enclaves and exclaves that had built up over centuries. The last of these to go, in 1974, was the detached part of Flintshire, otherwise known as the English Maelor, a tiny and oddly shaped nodule on the map that worried me enormously as a youngster, so abandoned and alone did it seem in the pages of the family atlas. It fascinates me still: I made one of my Welsh television programmes about the Maelor, despite the fact that no one there could watch it, for the little exclave pokes out into England, TV signal and all, and is connected to the rest of Wales by only the most slender of necks. As a local historian there told me in the programme, ‘When, in the 1990s, the boundaries were being redrawn yet again, the only option not presented to the people of the Maelor was the one that they probably wanted the most—namely, to be transferred over the border and into Shropshire or Cheshire. Very few people here feel any real affinity with Wales.’ As it was, the poor sods ended up as part of the new unitary authority of Wrexham County Borough, a fate you wouldn’t really wish on your own worst enemy.

The Maelor has been an exclave of Flintshire ever since it was given by the county’s progenitor, Edward I, as a gift to his beloved wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine (and as a nod back to the area’s previous incarnation as a widow’s dowry under the native Welsh ruler, Gruffudd Maelor). This act of gentlemanly generosity over seven hundred years ago has entirely coloured the culture and the flavour of the place, even today, for there is a neither-here-nor-there quality to the Maelor, an island remoteness that belies its firmly inland location. No one has captured this quality better than the late Lorna Sage, whose sublime memoir, Bad Blood, recalls growing up in the Maelor village of Hanmer, ‘a time warp, an enclave of the nineteenth century’, where ‘most engagements were really contracted between legacies and land, abutting acres, second cousins twice removed, or at least a tied cottage and a tea service’.

It was tidying up the many little islands of one county lost in another that first interested the government in fiddling with county borders; the Counties (Detached Parts) Acts of 1839 and 1844 rid us of scores of these outliers, although dozens still lingered, being abolished piecemeal throughout the next century or so. There were some strange bedfellows that surely needed sorting out: the villages of Icomb, Worcestershire, and Great Barrington, Berkshire, sat just five miles apart, both distant outposts of their respective counties deep within Gloucestershire. Even after the clean-up, Worcestershire still had eight lumps—four in Gloucestershire, two in Warwickshire, one in Staffordshire and one in Herefordshire—remaining outside the main county border. The most celebrated of these was the county’s ‘second town’, Dudley, which wasn’t transferred out of Worcestershire until 1966. Bizarrely, from 1889 to 1929, the parish of Dudley Castle was an exclave of Staffordshire, surrounded by an exclave of Worcestershire, itself surrounded entirely by Staffordshire.

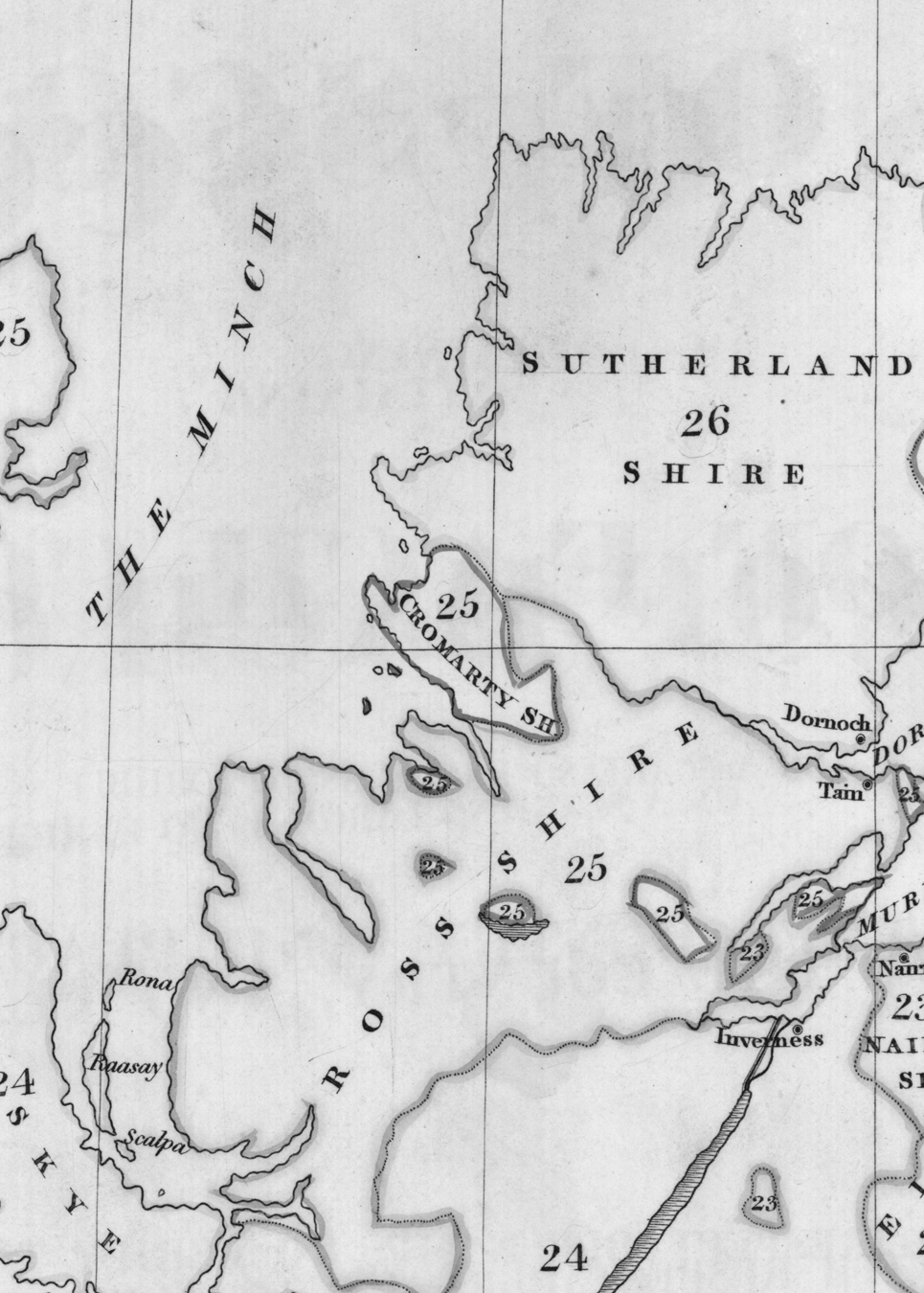

This was nothing compared with the situation in Scotland, however. Until the Local Government (Scotland) Act of 1889 tidied it up, the county map reflected its origins in the battles and bargainings of the clans and lairds, with numerous exclaves, some quite significant, on the map. Most remarkable was the county of Cromartyshire, which had grown out of the lands owned by the Earls of Cromarty, and was nothing but twenty-two completely separate parcels of land strewn across the entire width of Scotland, as if the whole county had been dropped and smashed by a fleeing giant. Only one nugget, around Ullapool on the west coast, was anything like a decent size at 183 square miles, slightly larger than Rutland, albeit in one of the least populated parts of Britain. The other twenty-one exclaves varied in size from twenty-eight square miles down to a tiny fifty-one acres at the tip of the uninhabited Gruinard Island, later infamous as the place where anthrax was tested on sheep in the Second World War.

The perpetual tinkering around with counties reached something of a peak in 1974, a landmark year for the map addict: two general elections (those constituency maps won’t just colour themselves, you know), the launch of the Ordnance Survey’s new 1:50 000 series in its startling pinky-purple jacket, as well as implementation of the most radical change yet in British counties. Cleveland, Merseyside, West Midlands, Avon, Strathclyde, the Central and Borders regions, Mid, South and West Glamorgan, Greater Manchester, Humberside, Tyne and Wear, and Hereford and Worcester were all created in a governmental bloodrush of clean lines, smooth edges and practical good sense. Sounding as though they’d been conceived and developed deep within the brutalist womb of a 1960s civic gulag, their birth wiped out at a stroke boundaries and loyalties that had worked quite adequately for centuries. Needless to say, the kind of people who get terribly exercised about such matters detested the new counties from the word go and lobbied tirelessly for their removal.

‘As if the county had been dropped and smashed by a fleeing giant’: Cromarty-shire

I was seven years old at the time and deliriously excited by the fact that, without moving so much as an inch, I had ceased to be a child of industrial north Worcestershire, but was now a proud resident of Hereford ‘n’ Worcester, the Sonny and Cher of English counties. I knew all the stats: how my county’s highest point, for instance, had rocketed from a fair-but-middling 1,395 feet (the Worcestershire Beacon of the Malvern Hills) to a super, soar-away 2,307 feet (a ridge, slap on the Welsh border, in the Black Mountains) just by the stroke of a pen. Never mind the fact that, by any definition, Kidderminster was a whole world away from the stark peaks of the Borders. It counted, it was official, and I hugged it close to my mappie little chest. I recall proudly announcing this revelation to my dad and step-mum, who just gawped in slack-mouthed incredulity at the weird shit that was tumbling from their little boy’s lips.

Even without the Ribena goggles of my childish enthusiasm, I still feel that the 1974 reorganisation has been rather unfairly done over. Faced with the dog’s dinner of administrative borders that John Major and the Boundary Commission have bequeathed us now, those reviled, abandoned ‘new’ counties are starting to take on a sheen of logic and clear thinking. Unlike our present system, the 1974 counties, and Scottish regions, were supremely easy to remember and to understand, with everywhere being served for one set of needs—mainly education, social services, transport—by its county council, the rest by its more local district council. And while some of them were undoubtedly a streamlining step too far, there was unshakable sense in many, particularly in metropolitan areas. After all, London—a metropolis that had once been carved up between Surrey, Kent, Essex, Middlesex and the City—had been redrafted as a single unit (the London County Council) as far back as 1889, and then expanded into Greater London, taking in more of each county and a slice of Hertfordshire for good measure, in 1965. What works for the capital was sorely needed in our other great conurbations. Until 1974, the urban West Midlands was cloven between three counties: Warwickshire, Worcestershire and Staffordshire (and, historically, the towns of Halesowen and Oldbury were in an exclave of Shropshire). Bristol was sliced in two between Gloucestershire and Somerset, the Newcastle/Gateshead sprawl between Durham and Northumberland. There was obvious room for improvement.

While the 1970s names and boundaries smelled of corduroy jackets on polytechnic lecturers, their 1990s replacements stank of the fudge and the focus group: truly the millennial way. On every decision, all it took was a few well-organised, very vocal protestors to whip up enough letters of support and the Boundary Commissioners collapsed in a funk. The result is there for all to see: I doubt if even the most avid, aspergic map addict could rattle off a complete list of current administrative British counties and county boroughs, a moniker that includes such mighty shires as Wokingham, Neath-Port Talbot, Renfrewshire and East Renfrewshire, Stockton-on-Tees, Halton, Thurrock, Rhondda Cynon Taff, the infamous Bath and North-East Somerset (aka BANES, with woeful accuracy), Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire and North-East Lincolnshire, but no other separate Lincolnshire from any non-northern point of the compass. Barely anyone knows where they all are, fewer still care. The administrative county map of Britain now looks as if it’s been left scrunched up under the stairs and nibbled by mice.

Nowhere is the post-war saga of county boundaries as defined or passionate as it is in Rutland, that Lilliputian East Midlands county that many people would probably struggle to place accurately on the map. ‘Have we been there?’ would be the brow-furrowed question, possibly followed up with: ‘I think we passed through it on our way to Norfolk once. Or was that Retford?’

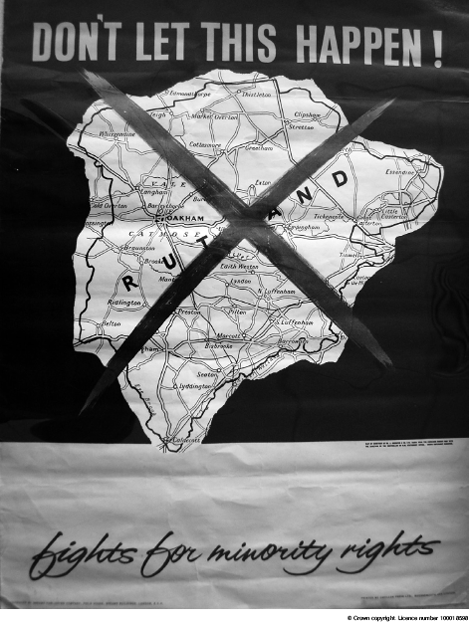

A poster from the Save Rutland campaign, as it swings into action in the early 1960s

Rutland may be tiny—in England’s smallest shire, you’re never more than seven miles from the border—but this is its greatest asset as much as its most obvious potential weakness. Everywhere you turn, it’s Rutland this and Rutland that: like small men and yappy toy dogs, it makes an awful lot of noise for its diminutive size. Local people think of themselves as Rutlanders or Ruddlemen first, English second. Being British tiptoes in behind, being European comes precisely nowhere.

Nothing ever unites a cause so magnificently as a threat to its very existence, and so it has been with Rutland. Since the Second World War, every one of the many government reports has recommended its abolition and incorporation into one of the neighbouring counties of Leicestershire, Northamptonshire or Lincolnshire. A county of just 36,000 inhabitants, they boom, is unviable and unsustainable. To offer the full range of goods and services demanded of a modern local authority is too prohibitively pricy and complicated for somewhere with such limited resources of manpower and revenue. The threat was seriously floated in 1962, when a government investigation recommended the abolition of a number of smaller counties. Rutlanders swung into action with a boisterous campaign to save their shire: a mock-up of naval warship HMS Rutland was placed in the middle of the county town, Oakham, bunting and a big banner declaring that ‘Rutland Expects’ flapping above it in the breeze. Various enthusiastic campaigners, often in military uniform, would megaphone passing shoppers from the pretend poop deck with the importance of saving their county status. One charming photo in the Rutland County Museum shows the ship in situ, with a comely maiden from the local girls’ grammar school in front, coyly holding up a placard that told the world that ‘Rutland Fights for Minority Rights’. When the campaign achieved its objective, and Rutland was (temporarily) spared the chop, the mock warship was quietly mothballed, but those who stashed it away knew all too well that it would probably be needed once again in the near future. And so it proved.

Rutland’s fighting spirit—and its plywood warship—was called on as never before as the swinging 1960s shuddered to a halt. First, there was the dastardly plan to create Europe’s largest manmade reservoir in England’s smallest county. ‘Don’t Flood Rutland’ and, rather more obliquely, ‘Don’t Reduce Rutland to a Tow-Path’, were the rallying cries for the campaign against a 3,100 acre artificial lake, almost the size of Windermere, at the tiny county’s heart. Newspaper headlines panicked about everything from parking problems to an influx of water-borne midges and flies. But voices in favour of the new reservoir—and the projected boom in tourism and property prices for houses with an unexpected waterfront view—began to sound, and in 1970 Royal Assent was given to the plan. By mid 1977, Rutland Water was open for business and the hamlets of Nether and Middle Hambleton had vanished beneath it. The larger settlement of Upper Hambleton remains to this day, isolated on a thin, ghostly finger of land poking out into the reservoir. The Water’s most famous spectral landmark, the lonesome Georgian church of Normanton, sticking out from the southern shore, looks as if it should tell the sad tale of a village recently lost beneath the waves, but the rest of Normanton was already long gone: the entire village had been demolished in 1764 under the orders of Sir Gilbert Heathcote of Normanton Hall, so as to improve the view from his splendid portico. Now that’s Rutland.

Ironically, by the time the local great and good had gathered to toast the opening of Rutland Water, the county from which it took its name had finally seen the waters close over its head. Rutland had managed to survive the tentative county cull of 1965 that had seen off the Soke of Peterborough, the Isle of Ely and Middlesex, but they were no match for Ted Heath and his determination to streamline the county map of Britain. In 1974, Rutland was annexed by neighbouring Leicestershire, being reduced to the status of a mere district council. Grinding salt into the wounds, Leicestershire County Council jobsworths even went round ripping out the Rutland signs and dumping them all. One by one, they were reclaimed and reappeared on the roads, where they still sit quietly today.

This being Rutland, however, the fight was only just beginning. The county never felt at home in Leicestershire: its modest population accounting for just 5.5 per cent of the new merged entity, its bucolic issues ignored by the pressing needs of a largely urban authority, whose principal city is due any day now to become the first in Britain with a majority brown and black population. It’s a long, long way from the quiet, honeyed—and overwhelmingly white—solidity of Edith Weston and Tixover.

Over the next two decades a groundswell of dissatisfaction with Leicestershire rule grew thunderous. Combining the increasing thirst for nostalgia, the growing scepticism towards politicians of all levels and the lack of understanding between the rural population and its urban, multicultural counterpart, the campaign almost ran itself. Every grumble and grievance was easily exploitable with the answer of: ‘It would all be all right if only Rutland regained its independence.’

The i-word is a real facet of Rutland’s identity: independence. They talk about it a lot, and chuck it around like verbal confetti. To a Ruddleman, it’s a word to stiffen the sinews, and it’s very telling. Here in Wales, politicians—even those from Plaid Cymru, for whom independence is their raison d’être—tiptoe around the word as if it might blow up in their faces, which indeed it might. No such reticence in Rutland. In the 1960s, they’d called out and marched to ‘Fight for Minority Rights’. In the late 1980s and early ’90s, such a slogan sounded either too monochrome or—heaven help us—as if they were proposing an enclave for Muslims or gays, so it was clear, simple and blunt: ‘Independence for Rutland’ went the cry. You get the feeling that if total secession from the UK was on offer, Rutlanders would grab it with both ruddy hands and the county would become a British Liechtenstein or Andorra, making its way in the world by selling postage stamps and duty-free, together with a little light tax evasion. At one point during the ‘independence’ campaign, they even issued Rutland passports as a PR offensive: the Republic of Rutland certainly has a bit of a ring to it. Its first piece of legislation would be to revoke the ban on hunting, its second the one on smoking.

In the end, the only independence on offer was that of a separate county council, which is hardly the stuff to get the pulse racing. It was enough, however, to take the county on its latest journey, as the Boundary Commission announced yet another comprehensive review of local government in the early 1990s. From the outset, Rutland was vocal in its demand for reinstatement on the county map, but the Commissioners showed no inclination to acquiesce. In 1995, there came a surprising volte-face when, out of nowhere, Environment Secretary John Gummer announced that he would allow the county’s reinstatement as a unitary authority. The burger-forcer had become the burghers’ hero, although rumours persisted that the nod had come from a higher authority, namely Prime Minister John Major. His constituency of Huntingdonshire had, until 1974, been a separate county (albeit with Peterborough tacked on the top for its last nine years), before being swallowed wholesale by Cambridgeshire. There was a half-hearted campaign running to reinstate Huntingdonshire, and Major thought it would be expedient politically if he backed it. To do so, he had to acknowledge the far greater strength of feeling in nearby Rutland, so he backed both horses. His own fell at the first fence, but the Rutland Pony powered on to the finishing line. On the strangely apposite date of 1 April 1997, Rutland was reborn. It’s a date still celebrated in the county as—you guessed it—Independence Day.

Except, it isn’t quite that simple. Rutland exists as a local authority, though not as a county in the eyes of the Post Office or in any of those choose-your-county boxes that you have to tick if buying something on the internet. The official name of the local authority is the gloriously tautological Rutland County Council District Council. To preserve its nominal independence, Ruddlemen have to pay one of the highest council taxes anywhere in Britain, with fairly patchy services in return. Furthermore, and with a grim sense of inevitability about it, those shrieking the loudest for ‘independence’ swiftly consolidated their own positions on the fledgling County Council District Council, and almost as swiftly descended into a mire of corruption and nepotism.

In Rutland, as in every place where localism is most politically charged, much of the campaign’s impetus came from incomers. While it’s an expedient pose for some, it is surely meant sincerely by many who, having come from elsewhere, truly value the distinctiveness of their chosen habitat and are desperate to see that not lost. This is certainly the case—and with good cause—in Rutland. Like the kernel of a nut or the bud of a new leaf, the 150 square miles of Rutland hold the essential imprint of England, or at least one particular version of England, the kind that likes its beef to be dripping with blood and its Saturday afternoons doing something with horses—either riding them, chasing small creatures with them or slapping money on them. Rutland is at the heart of English hunting country, it is modestly famous for its illustrious public schools, and, save for a few limestone quarries, industry’s grubby mitts have barely touched it. Since universal suffrage, and even during the Labour Party’s high-water marks of 1945 and 1997, Rutland has never elected anything other than a Conservative MP.

I knew that I had to take a trip to Rutland the day a mate told me that it was the wife-swapping capital of England; the Land of Rut indeed. My friend lives about fifteen miles away over the Leicestershire border, and told me of Rutland residents in her social circle who regularly find themselves at parties where a fumble in the hot tub is just for starters. These Rutlanders are commendably lacking in coyness, as you’d expect from people who spend large parts of their lives hanging around in the company of tons of quivering horse flesh and randy dogs. Lack of prudery, and a honest get-on-with-it lustiness, are undeniably central facets of the true rural existence—not the Move to the Country version, with its Chelsea tractors and stripped pine, but the real, hornyhanded version, more Massey Fergusons and stripped housewives. Rutland, true to its agricultural heritage, just likes to get ’em off and get on with it.

It was a bank-holiday weekend when I rolled into England’s minishire, and it was hard work finding somewhere to camp. By a stroke of luck that seemed to indicate that it was all meant to be, the only place available at the last minute turned out to be in the very village that I’d been reliably informed was the erotic epicentre of this libidinous little county. I pitched camp and wandered down into the village, through a typical bank-holiday torrential downpour. By the time I arrived at the pub, I was soaked. Thankfully, I was wearing a cap, so at least my head was relatively dry.

‘Bollocks! He’s already got a hat on,’ hollered a bloke at the bar as I entered the pub. ‘Well, sorry, mate, you’re going to have to get yourself another one.’ Only then did I notice that everyone was wearing a strange, and usually ill-fitting, piece of headgear. Three or four redfaced fellas sat at the bar beneath vast panamas. A lady in a trilby was swaying cheerfully by the dartboard. And my inquisitor peered out from under the rim of a white fedora. ‘Er, what’s it for?’ I ventured. ‘Oh, it’s a charity thing,’ he replied. ‘Distressed greyhounds or something. Go in that room’—he gestured towards the back bar—‘and pick yourself a hat for the night. Put 50p in the bucket.’ I meekly did as I was told, and came back in sporting a floppy summer hat, something I’d been meaning to buy anyway since getting painfully sunburned on my thinning scalp the previous week on a Norfolk beach. Bargain.

The hats definitely helped break the ice. According to my source, many of Rutland’s wildest parties originate in fancy dress: it’s not hard to see where a gathering is going when there’s someone in a PVC basque being led around the room on a dog chain; you’re not expecting Twiglets and a tombola after that. Although a pub full of people in daft hats isn’t quite so obviously designed to crank up the libido, there was something pleasantly anonymous about everyone being semiobscured by their hat, making conversation and shameless flirting a whole heap easier. I told one woman that I liked the top she was wearing. ‘Yeah,’ she drawled, thrusting her chest out. ‘I ’ave got great tits, ’aven’t I?’ She had, and was using them to devastating effect, particularly on the farm lad that I was hopelessly trying to chat up.

Like all good parties, time melted away into an impressionistic sweep of colour and raucous laughter. An Elvis impersonator serenaded us: as he was being paid, and as he had evidently put a lot of work and time into his stiff quiff, he was the only person in the pub allowed to get away with not wearing a hat. He was good, and just got better and better as the evening, and more especially the beer, wore on. Folk were amazingly friendly, and quite happy to chew the fat with a total stranger in a floppy hat. At one point, I was dancing like a loon to the ersatz Elvis, and noticing lots of hands covertly stroking lots of thighs—but, sadly, not mine—all over the pub. I’d make a useless undercover reporter, though, because with alarming speed at sometime after midnight, the world suddenly started to spin and I had to get out into the fresh air—the perils of being a crap drinker. As I whirled, green-faced, from the pub, the bird with the self-declared great tits grabbed my arm: ‘You going? Well, if you wake up in a few hours’ time, come back. We’ll still be going here.’ Rutland, oh Land of Rutting, you get my full respect for partying beyond the call of duty.

Of Rutland’s future, one thing is sure: it will retain its ‘independence’, even if it’s largely cosmetic. No fool politician is going to open up the can of worms marked ‘abolition’ in the foreseeable future. Such things matter in fretful old England these days: hanging on to the trappings of self-determination and localism, the baubles and the beads, the flags and the signposts, while trying to ignore the growing feeling that it’s only a matter of time before a barcode is tattooed on your forehead and your entire day could be reconstructed from CCTV footage. The harsh realities of modern life, though, come knocking here as much as anywhere else, and all too literally. The weekend I was there, the Rutland Mercury’s front-page splash was about the very village I was camping in. An extended family of Romany gypsies was hoping to set up permanent base there on a small parcel of land that they owned: two rival petitions—one hotly against them, one supporting their cause—were doing the rounds in the village. The ‘anti’ petition had chalked up over 400 signatures, the ‘pro’ one a rather less impressive 96. Now, the police were wading in and asking everyone to desist. Not desist collecting signatures per se, but desist from knocking on doors to collect them. ‘We are encouraging people…across the Rutland area not to open the door to strangers,’ the local inspector was quoted as saying. That’s going to do wonders for community relations; keep everyone bolted indoors, muttering conspiratorially to themselves.

This tiny storm-in-a-teacup hints at the darkest cloud looming over England’s dwarf fiefdom. Rat-race refugees—or rather, race refugees—are eyeing up Rutland’s rustic exterior and deciding that it has the edge over the various local sprawls—Leicester, Peterborough, Corby, Northampton—from which they hope to escape. Even with the slump, the local housing market remains feverish. With two-bedroom excouncil houses going for two hundred grand, few local youngsters have a snowball in hell’s chance of making it on to the first rung of the property ladder. While these pressures can be found all over the country, Rutland’s strident declaration of its independence and shrink-wrapped status can only exacerbate the problem: the more it makes of its uniqueness, its separateness, its crystallised Englishness, its 98.1 per cent whiteness, its dyed-in-the-wool Old Toryism and its diminutive size, the more eagerly it will be lusted after by that nomadic band of malcontents who twitch uncontrollably at the sight of anything multicultural and who are permanently searching for a bubble where it’s still 1959.

Rutland’s is an extraordinary story. The county’s civic motto of Multum in Parvo (Much in Little) is flaunted at every turn, and it underpins the identity of the place with unerring accuracy. To people in neighbouring, ‘normal’ counties, Rutlanders have the reputation as being rather above themselves and a mite snooty, as befits anyone who is part of a small clique, and in English terms, to be from Rutland is a clique that’s only marginally larger than being a paid-up member of the royal family. Size, it’s said, isn’t everything, but it sure is in Rutland. This monumentally proud, strange and utterly fascinating little county is like no other, and it’s all down to its pint-sized dimensions. In other words, the very uniqueness of the place, its every idiosyncrasy, comes from nothing more than a few random lines swirled on the map over a thousand years ago.

It seems that our attitude to our county borders has gone much the same way as our attitude to architecture, where each generation trashes the work of the one immediately prior to it. If that’s the case, we can look forward to endless rounds of boundary reviews, a situation designed to please only indolent politicians and their pet tub-thumpers in the regional media. Plus antiquarian map dealers: old county maps have become the mainstay of much of the trade, adorning a steadily increasing number of downstairs toilets and hallways, office foyers and CEO suites, particularly in companies doing their utmost to turn our urban environment into America Lite. By far the most popular sets among the many old county maps on offer are John Speed’s Tudor series and Thomas Moule’s early Victorian extravaganzas. Stunningly attractive syntheses of art and cartography, they are for sure, but they also have their own misty-eyed hunger for the past, so that it is our nostalgia for their nostalgia that drives the booming sales. Both Speed (1542-1629) and Moule (1784-1851) give us portraits of Britain at different high-water marks in our history, carefully editing out any details that left people unsure or apprehensive about the present or the future. Speed’s 1612 county atlas, the Theatrum Imperii Magnæ Britanniæ (‘Theatre of the Empire of Great Britain’), is a fine example of cartographic triumphalism. At that moment in history, the ‘Empire of Great Britain’ had spread no further than these islands; indeed, when he started working on the maps, Scotland wasn’t even part of this self-declared empire, and when it became so at the union of the two Crowns in 1601, Speed had hastily to amend his plans by introducing one map of the newly formed Great Britain, together with just one map of Scotland as a whole. This compared very poorly with the county-by-county maps of England and Wales, and poorly even by comparison with the four maps of the different Irish provinces.

Speed’s plans dwell fulsomely on all aspects of empire, both ancient and contemporary. His county plans bristle with civic pride and are dotted with depictions of royal residences, battles historical and legendary, aristocratic heraldry, Roman coinage and seas crammed with full-sailed battleships securing British coasts. Each county map comes with lavish notes, where truth is not always allowed to get in the way of his exuberant imperialism. On his Sussex map, he states as fact that 67,974 men were killed at the Battle of Hastings in 1066, despite our certain knowledge that it was conducted with considerably fewer than 10,000 soldiers on either side. Much of the mythology, enduring appeal and over-popularity of Stonehenge can be laid at the feet of John Speed, for he used it as the prime symbol of an ancient British empire, illustrating his map of Wiltshire with a massive drawing of it and wildly attributing it to the same kind of national heroism that his whole atlas was attempting to evoke. According to Speed, Stonehenge was ‘erected by Aurelius Ambrosius, King of the Britaines, about ye yere of Christ 475 AD’ as a memorial to his troops killed there by the ‘treachery of ye Saxons’. Other monumental stoneworks, such as nearby Avebury, don’t even merit inclusion on the map.

Even more telling are the English county maps of Thomas Moule, published as a complete collection for the first time in 1836. Like Speed’s atlas of two centuries earlier, Moule revels in proud patriotism and historical embellishment for each county. Embellishing most of the maps are chivalrous knights, high Gothic columns, pilasters and alcoves, stately homes and medieval cathedrals, bucolic scenes of cheery peasants at the water’s edge or herding stout cattle. Yet when the maps were published, the country was industrialising and urbanising at breakneck speed, with a concomitant revolution culturally and socially. The 1832 Reform Act, massively extending the franchise, had been bludgeoned through Parliament in response to considerable agitation; by the end of the decade, the Chartist movement was demonstrating fervently in favour of universal suffrage. Demonstrations, riots and fatal over-reactions by the authorities had placed the matter of workers’ rights centre stage. Canals had connected all corners of the country and created the first industrial conurbations, and now railways were accelerating that process in unimaginable ways. In the decade up to 1831, the populations of both Manchester and Liverpool had risen by nearly 50 per cent. When the London-Birmingham railway opened in 1838, some five million people used it in its first year. Everything was changing, but you’d never have known it from looking at Moule’s maps. They were a Picturesque flourish of lost lands and ways of life; in their day, they were already soaked in a wistful nostalgia. Now they seem doubly so.

Russell Grant, the diminutive astrologer, has become an unlikely champion for the old British counties. The interest started when he was a youngster, seeing his own patch of Middlesex so summarily disposed of in the mid 1960s. Twenty years ago, the publishers of his best-selling horoscope books told him that they would, as a reward for his prodigious and profitable output, publish any book of his choosing, fully expecting some vanity job. Instead, he produced a tome called The Real Counties of Britain, which sold oodles and has been updated and reprinted numerous times since. I interviewed him about the subject in Dolgellau, the solid old county town of Meirionnydd (Merioneth) for 438 years, until it was subsumed by Gwynedd in 1974. We did the interview sat on a bench by the River Wnion, Russell’s stumpy legs quite unable to reach the ground, which looked unintentionally hilarious when it appeared on screen. He was eloquent and passionate for his cause. ‘When I produced the book,’ he told me, ‘it really touched that part of the British psyche that needed to belong, that had allowed us to belong to a distinct area, and that had been the way for centuries, before the government began to muck them around. Those changes basically took away people’s sense of belonging; they often bore no resemblance to the familiar patches. Everything had to be bigger, which is not necessarily better at all, and they’re still tinkering with them now.’ He got quite agitated about the Ordnance Survey and how it is instructed by its government paymasters only to show the borders of local authority areas rather than traditional counties, but his greatest ire was saved for those individuals who include Torfaen, Medway, Thurrock or Inverclyde in their addresses: ‘As if the people who empty your dustbins warrant that kind of respect!’ he spat, his little legs swinging furiously.

Russell Grant is a leading light in the Association of British Counties (ABC), the rather more respectable campaign championing this persistent issue. Its more shadowy, renegade counterpart is the direct-action group, CountyWatch. Although it’s gone a little quiet in the last couple of years, CountyWatch hit many a headline in the mid 2000s by storming around the country and ripping up any county signs that were marking the borders of modern administrative areas instead of the traditional boundaries of the old counties. It was an inspired idea, gaining acres of publicity, annoying the hell out of local council jobsworths and absolutely delighting the sort of people who write at least one letter a week to their local paper.

Despite my fascination—and sentimental enthusiasm—for the old borders, I won’t be slipping on a balaclava and joining CountyWatch on a nocturnal patrol around the Yorkshire Ridings just yet. It’s a very fine line between getting rightly exercised about such matters and a whole hornet’s nest of petty obsession and some pretty dodgy politics. No surprise that many of the County Watchers are also active in hysterical (and often fabricated) campaigns about saving the pound (both kinds), the ounce, the yard, the mile, the pint, the sausage, the pork pie, real ale, Kendal mint cake, the countryside, Union Jacks on car number plates, hunting, shooting, fishing, Orange parades, school uniforms, parish councils, ‘God Save the Queen’ and the fancy dress of the Westminster Parliament.

Such obsessive upholders of tradition are themselves an age-old tradition, something probably worth preserving but not getting too excited about, like morris dancing or a half-arsed chorus of ‘Auld Lang Syne’ to see in the New Year. Absolutely every age has spawned its naysayers and nostalgists, folk who can only see the past in soft focus and the present through narrowed, bloodshot eyes—Alfred Wainwright would be cheering them on, for sure. Today’s bunch are the people who thought that BAN BLAIR was a cogent campaigning slogan and sprayed it over bridges, walls and roads like lusty tom cats. They see a sinister European plot behind everything and go right off the deep end about political correctness gone mad!, the BBC, multiculturalism, the ‘gay mafia’, the ‘Jewish mafia’, the ‘Scottish mafia’, global warming, secularism, Guardianistas, the ‘Islamification’ of Britain, New Labour, Cameron’s Conservatives and the LibDems. Which, you might think, leaves them electorally disenfranchised, but you’d be very wrong. These hecklers of modernity are just as good at inventing new political parties, and appointing themselves as leaders, as they are at creating vociferous new pressure groups. The angry nationalist right seems to schism on an almost weekly basis, so that nearly all of these dreary dissidents have passed through at least a couple of tiny political parties in much the same way that London drinking water is said to pass through numerous kidneys on its way to your glass. There’s always a gaggle of them standing in any high-profile by-election, blinking tetchily out from behind their bottle-bottom spectacles and homemade rosettes as the returning officer announces their 37 votes. Policies range from a mild harrumphing about modern life being simply beastly, to outright Holocaust denial and support for eugenic solutions. It’s a long way from worrying where Berkshire ends and Oxfordshire begins. Or is it?