Grope Lane in Shrewsbury - a slightly shorter name than before

7. CARTO EROTICA

Afterwards as she lay panting on her back, still naked, legs still splayed, she said, ‘I want to be fucked everywhere. In every hole. In every position. In every London borough. In every postal district.’

˜ Geoff Nicholson, Bleeding London

Comb any map and you will find a host of strange features: odd names, inexplicable and convoluted routes taken by lanes or paths, ghostly remnants of vanished communities, blank spaces where military establishments attempt to hunker down in cartographic secrecy. In only one place, however, can you find a complete set of genitals: Cerne Abbas in mid Dorset, its infamous chalk giant portrayed on eighteenth-century estate maps in full-frontal splendour. By contrast, the po-faced Ordnance Survey shows him as an outline, but have always coyly emasculated him, even on their largest-scale plans. Not that Cerne is the sole place to hint at the correlation between landscape and the erotic—maps bristle with sexual energy, places that have been known and marked since the earliest times as being laden with libido. Read ex-Teardrop Explode Julian Cope’s The Modern Antiquarian and you’ll start to see all manner of body parts winking knowingly from the landscape, their names often hinting at their ancient, fecund status.

The Cerne Giant is by far the most celebrated of ancient English chalk-hill figures, and for one reason only. It is a very good reason, mind you: a thrusting, rock-hard, thirty-foot-long reason, to be precise. In our phallocentric era, it’s no wonder that the Giant has become such a pagan icon for our times, combining, as he does, our twin preoccupations of sex and yesteryear. We want to believe that he represents an age and an attitude before we all started to blush and stutter at the first hint of anything sexual, that his proud, prodigious immodesty pointed straight back to a time when we could rut for England, and with no need for a little blue pill to help us on our way.

Some say, though, that the Cerne Giant points no further back than the seventeenth century. His first mention came in 1694, when the village churchwarden records paying someone three shillings ‘for repaireing of ye giant’, implying that the figure was at least a few decades old by then. This has led to numerous suggestions that he is little more than a cartoon character, carved in the chalk to lampoon a prominent figure of the day—the suggestion of Oliver Cromwell or Sir Walter Raleigh being particularly popular.

Most of us want to believe that His Perkiness is a great deal older and more venerable, for as archaeologist Rodney Castleden puts it in his book about the Giant, ‘absence of evidence is not evidence of absence’. After all, other chalk figures in southern England have been dated back thousands of years: the oldest we can be sure of is the otherworldly Uffington White Horse, alongside the Ridgeway in Oxfordshire. That has been carbon dated to around 1400 BC, from the Bronze Age, and what makes it so exceptional is that it is impossible to get a good view of it from the land: the only way of taking it in properly is from above. How was that achieved three and half thousand years ago? Horses are the most frequent chalk figures in the landscape: the only other ancient human figure is the enigmatic Long Man of Wilmington, exquisitely sited in a bowl on the side ofWindover Hill in Sussex. Like the Cerne Giant, many are desperate to believe that his origins date back thousands of years, but there is no empirical evidence from before the turn of the eighteenth century. And there is no truth either in the persistent rumour that, until the prudish Victorians excised them, the Long Man lived up to his name by sporting a set of genitals to outshine his Dorset counterpart.

Despite having seen him in countless photos and postcards or zoomed in on him on Google Earth, your first face-to-face encounter with the Cerne Giant is extraordinary. There he stands, naked, proud and very excited, emblazoned across a baize-green hillside above the sweet Dorset village of Cerne Abbas. Rosy-cheeked little schoolchildren skip around the playground under the arresting sight of a thirty-foot erection on a figure that’s nearly two hundred foot high. Not that the Giant has always sported quite such an impressive member (it accounts for some 15 per cent of the body length, which, if translated to a six-foot man, would be something over eleven inches): the earliest drawings, from the eighteenth century, and photos as late as 1902 show that since then the penis has grown upwards and annexed a now-vanished navel, believed to have happened during a 1908 recutting of the figure. At a few stages in history, it disappeared altogether: the Victorians filled in the ditches that made up the outline of his penis and planted shrubs over them. Ironically, that might be why the 1908 recutting got it so wrong and inadvertently created the supersized organ we see today.

We are fortunate that the Giant survived the Victorians at all: they thought nothing, after all, of chiselling suggestive sculptures off medieval churches and castles. Had the mooted railway line ever been built down the sleepy Cerne valley, the Giant would surely have been destroyed. Luckily, plans were shelved and the line was taken up the Frome valley, through nearby Maiden Newton, instead. It’s indicative of how far Cerne Abbas’s standing had tumbled over the ages, for this had been a major centre of some significance for centuries. The Giant aside, the valley is full of ancient trackways, tumuli and earthworks, and from the tenth century until its dissolution in 1539, Cerne’s Benedictine Abbey was one of the wealthiest and most important in southern England.

I finally made it on a long-awaited pilgrimage to Cerne in the spring of 1999, and found a place to camp on the village’s outskirts. There was no one else there for a whole four days, and my diary reminds me that it wasn’t until the third day that I even started to notice any other, less obvious parts of the Giant—the curious, blank face on his diminutive head, the pronounced nipples, the well-cut six-pack, the club being brandished in his left hand. Until then, I’d just been staring, mesmerised, at his erection, unable to drag my wide eyes away from its chalky magnitude. But there’s more to the hill than just the Giant. Above him is an ancient earthwork, known as the Trendle (aka the Trundle or the Frying Pan), which most historians, pagans and archaeologists reckon to be the epicentre of the hill’s magic and the probable precursor to the Giant itself. This is very much the view of Julian Cope, who writes: ‘I’m sure that the crass carving of Mr Big Dick was only done as a last resort when the religion was in such a poor state that they needed a logo, a prehistoric Ronald McDonald to get everyone excited again.’

On May Day morning, when the Giant’s penis is said to be precisely angled to the rising sun, the Trendle hosts the first ecstasies of the old festival of Beltane. They used to get a Maypole up there, though now it’s left to the Wessex Morris Men to dance in the dawn for an enthusiastic audience that almost invariably includes the odd bemused foreign TV crew. From my camping vantage point, the whole hill had begun to take on a supremely phallic form, as if this was a giant penis laid out in a far bigger recumbent-body landscape, a sacred form that stretched for five, ten, perhaps more miles across a huge swathe of Dorset. If that were so (and this came to me in such a blinding flash that I’d like to believe there’s something in it), then the Trendle would be the glans of the penis. Looking at the 1:25 000 map of the area, the contours of Giant Hill do indeed suggest an appendage of some kind, a high ridge of land jutting far out into the fertile valley that enfolds it. This could explain the slightly odd positioning of Cerne Abbey, and indeed the parish church, both placed below the tip in a perhaps futile attempt to neutralise, Christianise, tame the wild energies that flow from above.

Recumbent landscape figures, of all sizes, have long been a focus of our sacred quest, for they are a natural place to bring the spiritual realm into the physical one, representing nothing less than the figure of God, or the Goddess, on Earth. By definition, such figures make use of hills and mountains for their outline, inherently godly places for their greater proximity to the heavens, their other-worldliness, their extremes of elemental activity, the challenge that they demand of mortals to gain access to them and their long-standing attraction for pilgrims and hermits. Many of our recumbent landscape figures have standing stones aligned to them or forts and temples (latterly abbeys and churches) placed on them in key positions, some are aligned to particular risings and settings of the sun or moon: towering, massive landscapes that combine ceremonial art, astronomy, worship and nature.

They can be seen in all corners of Britain, none better than at the nation’s very edge in the Outer Hebrides, where the famous Sleeping Beauty (Cailleach na Mointeach, ‘hag of the moors’) is a spectacular sight from the standing stones of Callanish. If you’re positioned at the top of the main avenue of stones at the time in the 18.6-year cycle of the moon known as lunar standstill (and if you’re lucky enough to be blessed with a clear night), a sensational display unfolds. The low full moon rises perfectly over the belly of the figure, before gliding seductively up the length of the body’s curves, briefly hiding behind the ‘pillow’ hill, then reappearing in the very centre of the principal cluster of standing stones, before sinking back below the horizon. While this is undoubtedly Cailleach na Mointeach’s finest hour, the recumbent figure is an amazing sight at any time, as are others elsewhere: the Cuillins of Skye, Cumbria’s ‘pregnant’ Black Combe, Wales’ Pumlumon, Carn Ingli and Cribarth, Glastonbury and the Golden Cap, the highest cliff on the south coast of England. From a map addict’s point of view, the irony is that they are usually impossible to spot on an OS sheet, depending as they do on strange, sometimes fleeting, perspectives and optical illusions played by comparative distance.

According to renowned ley hunter Paul Devereux (in his and Ian Thomson’s book The Ley Guide), a seven-mile ley line begins at Cerne Abbas, with St Mary’s church, St Augustine’s well, the site of the abbey and the Trendle all in a straight line that then proceeds north and slightly eastwards to a tumulus, past a hill fort and, finally, to St Laurence’s church and the eponymous holy well at the village of Holwell. It’s easily traceable on the map, and goes directly along the length of the ridge line of Giant Hill, the undoubted cock in this magnificently randy landscape. Even a cursory glance at the map shows a wealth of Carry On names in the immediate locale: Lawless Coppice, Pound Bottom, Up Sydling, Hog Hill, Plush, Balls Hill, Navvy Shovel, Piddle Wood (and numerous other Piddles), Wancombe, Dickley Hill, High Cank, Smacam Down and, my personal favourite, Aunt Mary’s Bottom. There’s also a stark warning six miles north-east: the hamlet of Droop.

Despite all this, and despite our national love of a good innuendo, the village of Cerne Abbas itself was a curiously demure little place. The Giant is Dorset’s single most visited ‘attraction’, the area’s best-selling postcard and by far the most popular of our chalk-hill figures, and I was expecting the village to be something of a theme park, a Wicked Willy tearoom and a Cock Tails wine bar next to a place selling chocolate and wind-up joke penises, grotesque figurines and cock-swaggering T-shirts. None of it (at least not ten years ago. I see now that the Red Lion pub has renamed itself The Giant, and the website of a village trinket shop boasts of selling ‘Cerne Abbas Giant souvenirs, T-shirts, tea towels, aprons, mugs, pens etc.’. Only in true-blue rural England would something so primal be turned into aprons and tea towels). Back at the cusp of the new millennium, there was just one generic postcard in a few shops and, tucked away at the back of the newsagents, a slim volume about the Giant called The Rude Man of Cerne Abbas. In the gracious village parish church of St Mary (churchwardens Michael Fulford-Dobson and Clover Hartley-Sharpe), I checked the roll-call of christenings to see if there was any evidence of rampant fertility in the district, but it seemed distinctly lacking (unless, of course, there are loads of heathen nippers rampaging around the lanes, unblemished by a trip to the parish font). The list on the church wall showed that, in the previous ten years, practically every other baby in Cerne had been christened James—including, I suspect, a fair few of the girls.

Next to the official car park and viewing spot for the Giant is a great white gulag of a building staring slap at the chalk figure. Up on the hill itself and peering at it through binoculars, I decided that it was probably an hotel, though it looked rather too brutal even for a Travelodge. Later that night in one of the village’s pubs, I asked the gaffer what it was. ‘A loony bin,’ he answered immediately, before groping unsteadily for more politically sensitive terminology. But that’s basically what it is and what it was built for. It’s mainly full of elderly people in varying stages of dementia, and every day they sit in worn armchairs and look across the valley at this most exuberant celebration of vitality, tumescence and potency. If they weren’t nuts when they went in there, they soon would be: I’d only been looking at him for a couple of days and I was starting to feel distinctly crazy.

You get the unshakable feeling that Cerne Abbas has a slightly strained, faintly discomfited relationship with its most famous inhabitant. The landlord of the pub I was drinking in told me that he was extending it to include eight tourist bedrooms, which was bringing considerable local opprobrium winging his way. Up till then, there were only six B&B beds in the village, and that was the way people liked to keep it. On Cerne’s official website, click on Events and there’s no mention whatsoever of the May Day celebrations that bring in thousands of beardy pagans and cider-freaks. Instead, tourists are encouraged to attend Cerne’s equestrian endurance ride, the village cricket match, church fête or horticultural show. The official story is all briskly My Little Pony, rather than His Big Penis.

The British Board for Film Classification (BBFC) would perhaps disagree with my assertion that the Cerne Giant is the only set of genitals to be found on a map. In 1992, the BBFC reviewed its guidelines on what could and could not be seen by delicate British eyes. An erect penis was the final taboo, and to quantify their boundary between the acceptably limp and the unacceptably engorged, they came up with the assertion that ‘the angle of the penis to the body must not be greater than the angle of the Kintyre peninsula to the west coast of Scotland’. The ‘angle of dangle’ or ‘Mull of Kintyre’ rule, as it became known, was rigorously enforced until growing public exposure to the internet made the whole exercise redundant in the tsunami of hardcore that was engulfing a one-handed nation.

This arcane remnant of John Major’s Back-to-Basics Britain conjures up some surreal images. I picture a group of BBFC censors sat around and bumping some low-grade porn flick along from frame to frame. An actor starts to get a little excited. ‘Where’s the map of Scotland?’ hollers the chief censor. A flunky rushes to find it. ‘Hold it up, Brian, alongside his bits. Ooh, it’s almost there. Cut!’ Did the BBFC grade all other erections according to a chart of coastal protuberances, like an X-rated version of the Shipping Forecast? Was a Flamborough Head or an Isle of Thanet an absolute no-no, a Llŷn peninsula just a little too risky, a Spurn Head or the Lizard safely within the rules? That said, there is something undeniably penile about Kintyre on the map, and I’m sure it’s not just me and the BBFC who have noticed it. The shaft of the peninsula leans lazily out from the coastline, uncircumcised and drooping with just a hint of a bloodrush, before coming to a bulbous conclusion at the glans provided so thoughtfully by Mother Nature. To complete the picture, the neighbouring Isle of Arran makes a particularly convincing ball-bag hanging loose below.

Where nature has failed to provide a sufficiently phallic natural phenomenon, man has never been shy of augmenting it with his own. Many a Neolithic standing stone and monolith is unmistakeably priapic, and placed in its location either as a symbol of aggressive power or as part of a fertility cult: witness the royal Stone of Mannan (‘a giant stone penis’—the Daily Record) in the main square of Clackmannan; a stone circle of phalli at Aikey Brae near Aberdeen; Samson’s

The Scottish solution to the problem of the ‘angle of dangle’

Jack on Gower; the Pipers and Mên-an-Tol in west Cornwall; or the massive Obelisk at Avebury, in the process of being destroyed when antiquarian William Stukeley visited and drew it in 1723, placed as it was in a position opposite the ‘vulva stone’, which thankfully remains with us. That so many standing stones and stone circles had ancient sexual connotations is indicated by their being given Christianised names to do with the devil, or the common myth that they are the bodies of debauched revellers frozen in stone for debasing the Sabbath. Such Puritan overlays tapped into genuine folk memory, passed down through the generations.

Places that exude a female sexuality are, self-evidently, far less overt. Estuaries, fertile plains, river valleys, caves and fogous, barrows, cairns and mother mountains can often be identified on the map by their shape or feminine name; hills such as Mam Tor in the Peak District, Moel Famau (‘the rounded hill of the Mothers’) in the Clwydian range of north Wales, Mither Tap (‘Mother Tit’) in the Grampians and the proudly swollen Paps of Jura. More often, though, it’s a much more subtle sensuality that marks out a place, something that may only be apparent if you are receptive enough to notice it, or go somewhere often enough to get to know it intricately. A map won’t be much help here. There’s a fertile little cwm—that Welsh word for a small, sweet, damp cleft in the hillside—near where I live that has whispered vagina energy to me from the day I first moved here. I’ve walked near and in there with numerous people, and quite a few have picked up exactly the same sensation with no prompting at all from me. I wasn’t surprised to learn from a friend who’d grown up here that she used to be taken up to this cwm as a teenager to partake in ancient family witchcraft rituals deep in its mossy folds, as part of an all-female coven of local women.

As the West takes on a more feminist, or at least feminine, agenda, there are many signs that this guile and subtlety of old is changing. Had plans worked out, the Ordnance Survey would now be updating its Newcastle-on-Tyne map to include an explicitly naked female figure, five hundred yards long and with breasts well over a hundred feet high. Unlike the flat chalk outline at Cerne, breast mounds of that size would appear as contours, so there would have been no way the OS could have coyly left off the rude bits in the way that they do with the Giant. The figure, named Coventia, after a Northumbrian water goddess, was planned by architectural sculptor Charles Jencks, designer of the much-lauded Landform installation at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and the delicious Garden of Cosmic Speculation at his own home in Dumfriesshire.

The inevitable controversy seems to have sunk the project, probably for good. Local Christian groups objected to it—not to the thought of a third-of-a-mile-long naked Amazon reclining in their landscape, but because she was to be named Coventia, which they claimed encouraged paganism. As a result, the lady had her name changed to the revolting municipal fudge of Northumberlandia. Some people objected to the sheer scale of the figure (it was even said that it could endanger pilots landing at nearby Newcastle Airport), so the council ordered that its size be reduced by some 40 per cent. There was a far greater controversy, however, lurking behind the plan, in that it was a sop for a scheme to open a huge opencast coal-mining operation on the site; Northumberlandia was to be a novel use of the slag that would accrue as a result. The headlines almost write themselves. The mining company had cleverly diverted everyone’s attention with the giant goddess, and it was left to local councillor Wayne Daly to remind them that ‘this is an application for opencast mining, not an application for a woman with 150-foot breasts in South-East Northumberland’. The council finally turned the proposals down, thoroughly annoying the mining company and, it seems, the government, who is threatening to overturn the decision. Should it ever get the go-ahead, I would happily bet that poor old Northumberlandia will never feel the north-east breeze billowing over her generous contours.

When it comes to the overt sexuality of place, some women happily take men on at their own game. Eve Ensler, the feminist creator of The Vagina Monologues, chose New Orleans as the place to hold the tenthanniversary party of her hit play. And why? Because, of course, she sees it as ‘the vagina of America’. ‘It is fertile. It’s a delta. And everyone wants to party there,’ she explains, backing up her theory with a map of the area. One of her Monologues actors, Kerry Washington, was initially aghast at the idea, saying: ‘When Eve told me New Orleans was the vagina of America, I was like, oh sweet Jesus. Sometimes I think, Eve, do you really want to go there? Really? But now I get it. New Orleans is sexy, everybody loves it—but when it has problems, nobody wants to know.’

The female equivalent of the Kintyre peninsula is most commonly cited to be the island state of Tasmania, off the southern coast of Australia. The shape of the island has long been infused with a certain innuendo, to the point where the phrase ‘the map of Tassie’ has become regular Aussie slang for a woman’s pubic region (‘open up the map of Tassie’, and so on). While it’s not unusual to be able to buy souvenir tea towels and the like emblazoned with a tourist map of Shakespeare Country or Bonnie Scotland, in Tasmania you can purchase not only those, but also pairs of panties with a perfectly placed map of Tassie on the front panel—a memento doubtless bought by far more men than women. A recent Australian TV weather forecast saw the reporter point to the map of Tasmania, and innocently say, ‘Looks like it’s pretty wet down there,’ which sparked off much blokey guffawing in the background of the news studio.

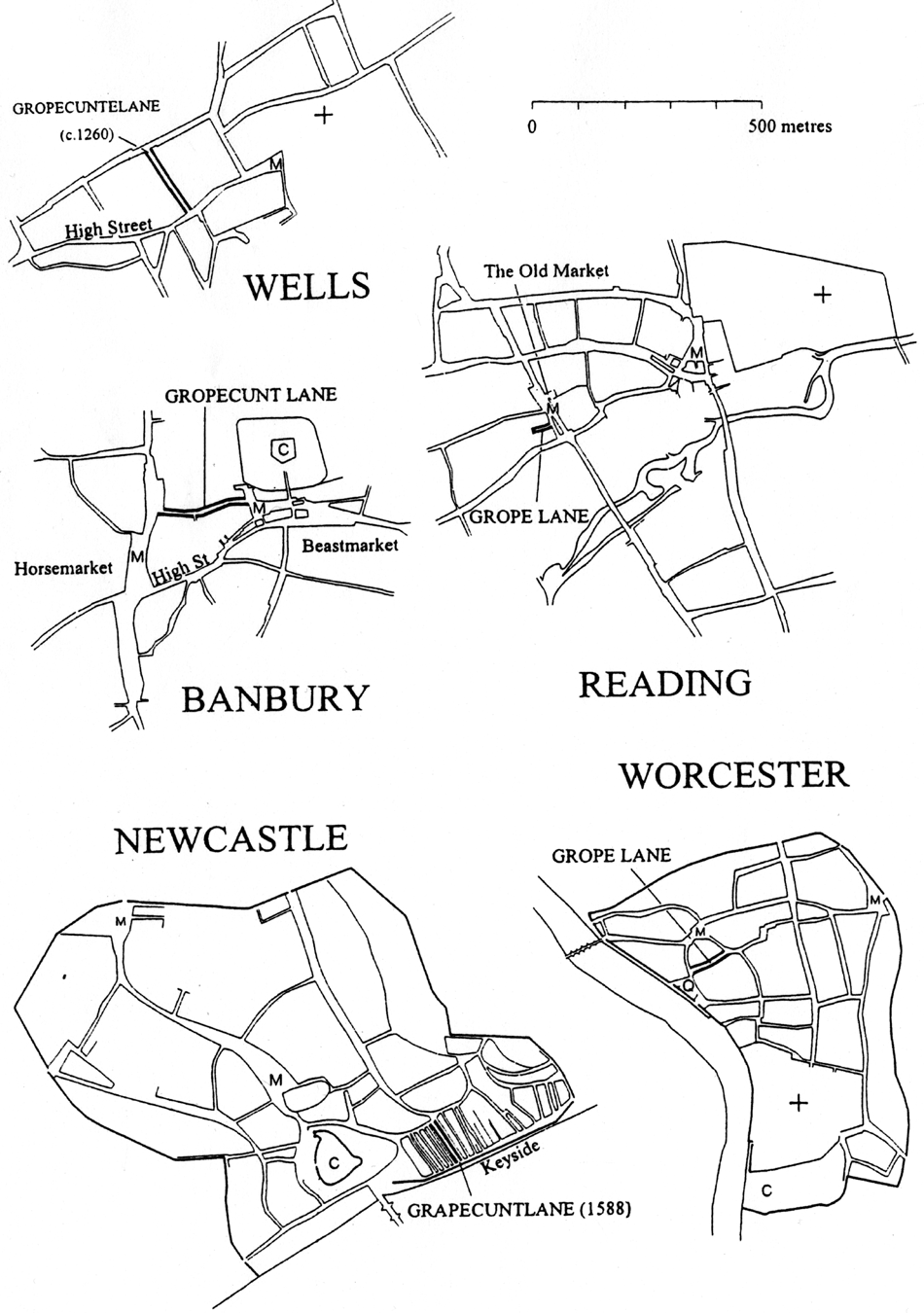

Before street maps became widespread and roads were named in whimsical or Arcadian ways, people had to rely on the literal streetscape of a town to navigate their way around, giving us the legion of Church Lanes, School Roads and High Streets that still form the backbone of our A-Zs (High Street being by far the most common road name in the UK: there are some 5,410 of them). Often, names were culled from trades: Tanners’ Row, Smith Street, The Shambles and so on. Where the streets have survived, so have the names, unlike one that said all you need to know about a very popular business; one that, unlike the tanners and smiths, is still with us. Many medieval towns had a Gropecunt Lane, for the c-word wasn’t anything like the verbal nuclear warhead that it is today, and streets of this name—mostly putrid alleyways somewhere near the town’s main market—were recorded in London, Oxford, York, Norwich, Bristol, Newcastle, Southampton, Hereford, Leeds, Wells, Banbury, Northampton, Peterborough, Reading, Whitby, Worcester, Shrewsbury and Dublin. As the name so precisely implies, these were where any gentleman, landing in a strange town for commerce or a coaching stop, would be guaranteed to find a little action from a range of lead-faced whores. Prostitution was almost as respectable a part of a town’s mercantile range as horseshoeing or ale-brewing, so wasn’t pushed out of the main drag by squeamish sensibilities. When visiting a new town these days, I apply much the same rule in finding a good breakfast: the area around the market and/or the bus station can normally be relied on to produce the best greasy spoon. Today’s stomach-bloater on the site of yesterday’s knee-trembler: there’s progress.

An assortment of medieval Gropecunt Lanes

Unsurprisingly, none of the Gropecunt Lanes have survived the zeal of the censors, although Shrewsbury’s is the best extant example. The town is famous for its twisting, medieval passageways, known locally as ‘shuts’, and there, typically near the site of the old market, is Grope Lane, a narrow defile that zigzags its way down to the main square. According to a directory of the town’s street names and an MA thesis, both in the town’s archive library, it was named Gropecount Lane in a property deed of 1325, and was still called that as late as 1561. The 530-page thesis, Shrewsbury: Topography and Domestic Architecture, was presented to the University of Birmingham in 1953 by one J. T. Smith, although he got his father to do the indexing. Dad, evidently, was either slightly shortsighted or had his prudish hackles raised by the name, for it appears in his index as the far more fragrant Grope Court Lane. The street-name directory goes for the same explanation of Grope Lane’s etymology as does the local tourist board these days: trying to conjure up the image of people having to grope their way along its rickety walls in near darkness. It doesn’t wash. Everything about the passage reeks of dropped britches and loveless fumbles, even today when the only thing down there that will get your pulse racing is a branch of Costa Coffee.

Oxford’s version is the earliest mentioned in documents (as Gropecunte Lane, c.1237). It is tucked away between the High Street and Merton College, and mutated into Grope Lane, then Grove Street and finally into Magpie Lane, the innocuous moniker by which it is still known (and near where the habitual old groper himself, Bill Clinton, lodged when in the city as a Rhodes Scholar). Grove Lane or Street was the commonest rechristening, although London’s famously seedy Grub Street, now Milton Street by the Barbican, and Grape Street in Holborn both possibly hark back to more immodest origins. Certainly, they are located in the right parts of town: just outside the city walls, the hotspot for all of London’s seamier doings. Likewise, over the river in Southwark, long the haunt of hookers, actors and cutpurses, there’s still a Horselydown Lane almost under Tower Bridge. It may be a corruption of ‘Whores Lie Down Lane’, though it’s more likely to be the lea (meadow) of horses rather than prostitutes prostrating themselves; indeed it’s hard to imagine any medieval slapper taking it lying down in the filth of a Southwark alley. There’s a popular, internet-fuelled contention that Threadneedle Street in the heart of the City of London also began life in this way, and that its new name is just a euphemism for its old one. While it’s sorely tempting to think of the Bank of England as ‘the Old Lady of Gropecunt Lane’, the road has always surely been too important and too busy for alfresco rutting.

Cast-iron evidence for any of London’s Gropecunt Lanes is sparse. There’s an OED definition from 1230, together with deeds and other legal documents from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. From these, we learn that the only definite example in the capital ran from the south of Cheapside to the vicinity of St Pancras church. The church is long gone, but Pancras Lane still exists, one block south of Cheapside. Either side of Gropecunt Lane were Soper Lane (now Queen Street) and Bordhawe Lane, a name that may allude to whores and/or their bordel or bordello (although I rather prefer to think of the eponymous Bored Whore examining her crusty fingernails while some fat punter grunts away at her against the wall). At first glance it seems that Bordhawe Lane has vanished as mysteriously as its neighbour, but maps from the eighteenth to the early twentieth centuries record Bird in Hand Alley and Court, which could be what it became. These are first recorded off 76 Cheapside in 1677, after the whole area was razed to the ground in the Great Fire a decade earlier. The second Great Fire—the Blitz—saw them off for good.

There’s much to be said for the literal nomenclature of medieval streetscapes. We could do with a bit more of it today: sweep away the legion of King’s Meadows and Willow Heights for the rash of soulsapping executive developments whose names seem to have been plucked from a focus group random-word generator. On the rare occasions that the names do have any tenuous relevance to their location, it’s only to tell us what was once there and has now been forever trashed by the spreading syphilis of brick boxes. Let’s see Barratt, McAlpine and the rest inviting us to their show homes at Rabbit Hutch Close or Battery Hen Drive. Eponymous exactitude was a wonderful feature of a medieval town: you’d be in little doubt what to expect in, for instance, London’s Hookers Court, Dunghill Lane or the numerous Pissing Alleys and Dirty Lanes. And it wasn’t just the odd Gropecunt Lane that could beguile you into its dank environs: politer towns would offer you much the same service in Maiden Lane, a name that has often survived. In the scrofulous slums around Cheapside, for centuries the capital’s main commercial thoroughfare, one of the Maiden Lanes sat bang opposite Lad Lane: left for a trollop, right for a rent boy. If you wanted to hedge your bets, the next street up was Love Lane.

The maps have long been excised of their harlots and piss-pots, but there’s still plenty enough smut on the Ordnance Survey to satisfy anyone’s inner adolescent. A recent Christmas stocking-filler book, Rude Britain, became an instant best-seller, filled with photos of signs pointing to the likes of Twatt, Pratt’s Bottom, Penistone, Minge Lane, Thong, Brown Willy and Lord Hereford’s Knob. Perhaps thanks to the local accent, which can make even a shopping list sound bawdy, the West Midlands seems to be a particularly rich seam of cartographic coarseness. When I lived in Birmingham, I plucked infantile delight from taking visitors to one of my favourite Black Country pubs, the Dry Dock at Netherton, probably the only boozer in Britain to contain a narrowboat. To get there from Brum required a drive down a road named Mincing Lane for its first half, and Bell End for the second. This took you into the district of Cock Green, from where a left turn would whisk you to the pub in the area known as Bumble Hole, at the top of Powke Lane. And as if one Bell End wasn’t good enough, there’s also a nearby hamlet of the same name, just north of Bromsgrove, and only a couple of miles from its natural twin, the village of Lickey End, which comes complete with a road named Twatling Lane. I grew up less than a dozen miles from all of these, which possibly explains quite a lot.

There are occupational hazards to living in a place with a piquant name. Villagers in Fucking, a tiny dab of a place twenty miles north of Salzburg in Austria, have become so fed up of carloads of Brits gurning for photos at the village sign that they held a vote in 2004 on changing its name (they decided against). The trend started during the Second World War, when American and British soldiers stationed nearby first noticed the village and came for photos. Now, though, coming away with a picture is nowhere near enough: punters want the sign itself and are arriving after dark with a bag of screwdrivers to get it. In one night in 2003, all four village signs vanished, and replacing them has been a major burden on local taxes. The response to the thieves was to replace the signs with ones bolted and welded to steel posts, embedded into concrete blocks in the ground. The locals are not amused. The police chief stated: ‘What is this big Fucking joke? It is puerile.’ Tourist guide Andreas Behmüller expanded on our love for his little village: ‘The Germans all want to see the Mozart house in Salzburg. Every American seems to care only about The Sound of Music. The occasional Japanese wants to see Hitler’s birthplace in Braunau. But for the British, it’s all about Fucking.’ None of them, sadly, explained what residents of the village are known as—nor, indeed, their mothers.

Road-sign larceny is a growing headache for anywhere with a bawdy name or association: those of Llanddewi Brefi, the peaceful Cardiganshire village whose name was plucked off the map and used as the home of Dafydd, ‘the only gay in the village’ in the Little Britain TV show, were, at the height of its success, being half-inched regularly and even ended up for sale on eBay. At the other end of Wales, the two signs pointing towards the village of Sodom rarely survive longer than a month or two before having to be replaced. The village of Lunt, just north of Liverpool, is considering changing its name as folk can barely scrape the paint off the sign before the L is defaced yet again to the inevitable C.

If British censors had to excise a few earthy bodily functions from the map, no surprise that their American counterparts were dealing with a plethora of names that told us all we ever needed to know about that country’s troubled history of matters—and manners—both sexual and racial. As the pioneers swept west, features were named and mapped with monotonous inevitability: any hill west of the Appalachians that looked even faintly breast-like would become Squaw’s Tit, Squaw’s Teat, Squaw’s Nipple or some variety thereof. An entire roll-call of playground insults included Dago Gulch (Montana), Nigger Pond and Niggerhead Point (New York), Niggerskull Creek (North Carolina), Jewtown (Georgia and Pennsylvania), Gringo Peak (New Mexico), Jap Bay and the frankly fabulous Jap Gap (Alaska), Dago Joe Spring (Nevada), Gook Creek (Michigan), Chinks Peak (Idaho), plus hundreds and hundreds of other variants. As sensibilities have changed, their gradual renaming has caused endless argument, in State assemblies, local courts, the Federal Board on Geographic Names, even Congress and the Senate. The argument almost always goes the same way: someone will roundly defend the names against the ‘political correctness’ of their suggested replacements, petitions will be gathered, local radio shock-jocks will shout and holler. Signs get defaced, replaced and stolen, and politicians are left to tiptoe a wary line through the linguistic minefield.

The internet has brought untold erotic possibility into our libidinous little lives, including a phenomenon known as the Sex Map, or Shag Map. It’s exactly as you’d expect: a map of places associated with your own sexual history; there are entire websites dedicated to plotting and sharing them. And they were around way before the World Wide Web came to dominate our nocturnal lives. Geoff Nicholson’s Whitbread-shortlisted novel, Bleeding London, has a character, Judy Tanaka, quoted at the top of this chapter, who wants to be laid in every London postcode district. The wall of her bedsit is covered with a huge street map of the capital, over which she lays different clear plastic sheets. All her visitors get a sheet to themselves and are asked to mark with a cross everywhere they’ve had sex: ‘There were people whose maps centred intensely around Kensington or Belsize Park, others who were concentrated on south London, others who had lived and fucked all over London at every point of the compass.’ This got me thinking. Was there one single existing map that could best encompass my own sexual history? The answer was a blindingly obvious yes. I’d like to claim that it was a plan of the boulevards of Paris, the beaches of Spain, the mountains of Wales or even a corrupted version of the London tube map, a spiced-up game of ‘Mornington Crescent’, if you like. But it’s none of these. It’s page 90 of the Birmingham A-Z.

I lived and loved on that one page of the second city’s street atlas between the ages of twenty-four and thirty-three, and I’m sure I’m not the only one to have found this stretch of south Birmingham an erogenous zone of epic proportions. Page 90 has long been the city’s boho quarter, a place for hippies, punks, squatters, junkies, queers, partyheads and polyamorists, sprinkled among the tight terraces of Balsall Heath and the gracious Victorian villas of Moseley. It was a fabulous place to have a second adolescence.

The heady erotica of the BirminghamA-Z is just a warm memory these days. Now my thrills have to come from an even less likely cartographic source: the National Trust Map of Properties. It was inevitable that someone who started collecting Ordnance Survey maps at the age of seven would end up as a member of the NT. And if you consider that the only other probable outcomes to such an early start would have been to end up as a Neighbourhood Watch coordinator or a volunteer on a steam railway, I may well have got away relatively unscathed. There is plenty of time yet, mind.

I love the National Trust. For all their po-faced earnestness and clumsy attempts to repackage themselves in trainers rather than Hush Puppies, they remain one of the finest, quirkiest and most delightful organisations in the land. With a few clear days in a new part of the country, nothing compares to the frisson of anticipation that comes with the first opening of the NT map to see what unexpected treats the area has to offer. I know full well that, a few days and a good few Trust properties later, I will emerge a wiser, happier man for having been allowed to wallow in things of exquisite beauty, exquisitely well presented. I will have had numerous cheery exchanges with other members of the cult, anything from a collaborative smile over a slice of cherry cake in the tea room to a sparky discussion about the eighteenth-century Grand Tour or the Enclosure Acts with one of the erudite volunteer guides sprinkled around each property. I haven’t quite yet made the leap into striking up easy conversation with many of my fellow NT members: should that happen, I’m terrified that I’ll start buying all my clothes from the catalogues that fall out of the Radio Times, and end up looking, like rather too many of the male members, the spit of Harold Shipman.

An NT property—especially outwith the school holidays, when it’s just me, the Harold Shipmans and their mousy wives visiting—is a failsafe ego boost. In an occurrence that’s increasingly rare these days, I’ll be well within the bottom ten per cent of the age range, a thrill that makes me positively sashay up to the front door. Not that anyone will notice, as they’ll be far too busy adjusting their bifocals, unpacking the thermos and having an argument in tetchy whispers about missing the turning for the B5818 twelve miles back.

The Trust is desperate to modernise, although the irony is that it is its inability to do so that stirs such loyalty in the breasts of the Tupperware generation. There are glimpses that the twenty-first century has arrived, however. I first joined because I felt sorry for the two fragrant ladies on their stall at the National Eisteddfod, the AGM for Welshspeaking Wales. There are hundreds of stalls at the Eisteddfod, though the ones that pull the crowds are those of the publishers, record companies, funky-clothes sellers and protest groups. The NT stand, reeking of lavender and Middle England, had a rather abandoned air, as if no one had been in there for hours. Initially to shelter from the rain, I popped my head around the canvas flap to be greeted by two hugely relieved matronly faces. They were having such a quiet time of it, I felt slightly obliged to join up, and even enrol my partner too, just for the pleasure of seeing their little faces light up at having flogged a joint membership. Her pen poised over the application form, one of the ladies smoothly enquired, ‘And Mrs Parker’s name is…?’ ‘Er, my partner’s a man,’ I replied. Without missing a beat, she smiled and said, ‘How nice…and his name is?’ We were in the club, even if my boyfriend promptly lost his membership card, possibly as a quiet protest.

Membership means that you’ll often go to places that you might otherwise not have bothered with (the urge to ‘earn’ back the cost in offset entrance fees is scarily strong), and stumble accordingly across some real unexpected gems. The delicious irony is that this most buttoned-up of British organisations is the key to some of the country’s dirtiest secrets, for no one does depravity quite like the upper classes. Perhaps the Trust’s most libidinous landscape is West Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, built and laid out to the very specific tastes of its eighteenth-century owner, the legendary libertine Sir Francis Dashwood, founder of the notorious Hellfire Club. His Palladian mansion is an orgy of marble, statuary and frescoes, much portraying naked nymphs, centaurs, satyrs, cupids, and goddesses with generous curves and golden curls, but it is in the surrounding parkland that he let his fantasies run riot. The centrepiece of the park was a nine-acre lake in the shape of a swan. In his History of Gardens, Christopher Thacker, quoting from a volume of Victoria County History, describes how Dashwood’s lake and gardens were ‘laid out by a curious arrangement of streams, bushes and plantation to represent the female form’, but one as far from the craggy mountain recumbents of the Hebrides and Wales as could possibly be imagined.

In his book The Hellfire Club, American author Daniel P. Mannix is far more explicit. He asserts that two mounds were each topped with a circle of red flowering plants, and that, at a little distance below and between them, was a triangle of dark shrubbery. The effect was particularly startling from the top of West Wycombe Hill to the north of the park, where Sir Francis had lavishly rebuilt the church of St Lawrence. To best enjoy his view, he crowned the church tower with a golden ball, into which he and half a dozen friends could comfortably climb and dine. Mannix states that Sir Francis once took the local priest up the tower to show him the parkland. He asked him, ‘What do you think of my gardens?’ at which point, by prior arrangement, the fountains started. Two of them spouted a milky-white fluid from the top of each red-flowered mound, while the third gushed from the area of the shrubbery. The priest’s response is not recorded.

As if the landscape needed much more to underscore its theatrical erotica, the parkland was littered with lascivious statuary, temples, grottoes and follies, the least subtle of which is the sole survivor of the recumbent female form, the Temple of Venus. This homage-in-flint to the female genitalia has two curving walls centred on a coy slit that opens into a grotto beneath an earth mound; it reminded me instantly of the many swollen-goddess burial chambers that I’ve squatted in, such as Belas Knap and Hetty Pegler’s Tump in Gloucestershire, Bryn Celli Ddu on Anglesey and the West Kennet barrow in Wiltshire. In Sir Francis’s day, an erect flint pillar stood in front of the opening to his temple and dozens of naked statues decorated the scene, including one of Mercury, a wry nod to the liquid metal’s status at the time as the only known treatment for syphilis. When Sir Francis’s far more straitlaced nephew inherited the estate at the end of the eighteenth century, he wasted no time in destroying the Temple of Venus, the female body alignment and many of the other more suggestive features of the park. It wasn’t until 1982 that Sir Francis’ namesake, the 11th Baronet, restored a version of the temple that we see today.

That Sir Francis’s lake was swan-shaped is thought to have been inspired by the myth of Leda, Queen of the Spartans, who was raped and impregnated by the god Zeus in the shape of a swan, on the same night that she also made love to her husband, Tyndareus. This, together with the almost pastiche version of female sexuality that the gardens represented, suggest that the entire enterprise was very much the notion—fervent wish, perhaps—of feminine libido seen through the eyes of men; terminally adolescent men at that. The same could perhaps be said of poor old Northumberlandia, the naughty knickers of Tasmania and maybe even Julian Cope’s fervent desire to see a fertile landscape goddess around every corner. Mapping and sex seem to prove that the phrase ‘adult male’ may well be an oxymoron.